Summary

In Gram negative bacteria, thiol oxidoreductases catalyze the formation of disulfide bonds (DSB) in extracytoplasmic proteins. In this study, we sought to identify DSB-forming proteins required for assembly of macromolecular structures in Legionella pneumophila. Here we describe two DSB forming proteins, one annotated as dsbA1 and the other annotated as a 27-kDa outer membrane protein similar to Com1 of Coxiella burnetii, which we designate as dsbA2. Both proteins are predicted to be periplasmic, and while dsbA1 mutants were readily isolated and without phenotype, dsbA2 mutants were not obtained. To advance studies of DsbA2, a cis-proline residue at position 198 was replaced with threonine that enables formation of stable disulfide-bond complexes with substrate proteins. Expression of DsbA2 P198T-mutant protein from an inducible promoter produced dominant-negative effects on DsbA2 function that resulted in loss of infectivity for amoeba and HeLa cells and loss of Dot/Icm T4SS-mediated contact hemolysis of erythrocytes. Analysis of captured DsbA2 P198T-substrate complexes from L. pneumophila by mass spectrometry identified periplasmic and outer membrane proteins that included components of the Dot/Icm T4SS. More broadly, our studies establish a DSB oxidoreductase function for the Com1 lineage of DsbA2-like proteins which appear to be conserved among those bacteria also expressing T4SS.

Introduction

Legionella pneumophila, the etiological agent of Legionnaires’ disease (McDade et al., 1977), resides in aquatic environments as an obligate intracellular pathogen of amoebic hosts (Fliermans et al., 1981; Rowbotham, 1980; Fields, 1996). Within these hosts, L. pneumophila displays a dimorphic life cycle, alternating between intracellular vegetative replicating forms (RFs) and extracellular planktonic non-replicating cysts that are metabolically dormant, resilient, and highly infectious (Garduno et al., 2002). The ability to differentiate appears to be a fundamental survival characteristic of this species which can also be activated in RFs upon: (i) suspension in water (Garduno et al., 2002; and Hiltz et al., 2004); (ii) ingestion by inappropriate hosts such as ciliates (Berk et al., 2008, Faulkner et al., 2008); or (iii) within the gut of nematodes (Brassinga et al., 2010). Ultrastructural studies of cysts reveal extensive remodeling of the typical Gram negative envelope to a complex thickened cell wall overlaying laminations of intracytoplasmic membranes (Faulkner et al., 2002, Garduno et al., 2002). Comparative proteomic analyses of these forms identified 30 proteins that were more abundant in the cyst than in stationary phase in vitro-grown bacteria, including MagA, which is a marker of differentiation that is located in a genomic island (Brassinga et al., 2003; Hiltz et al., 2004). Consistent with remodeling of the cell envelope were changes in the pattern of outer membrane proteins and enrichment of the HtpB invasin on the cyst surface (Garduno et al., 1998a; Garduno et al., 1998c; Garduno et al., 2002). The molecular mechanisms associated with the extensive remodeling of the cell envelope during morphogenesis are poorly understood.

Other macromolecular complexes associated with virulence traits of L. pneumophila include components of the Dot/Icm type IV secretion system (T4SS) (Berger and Isberg, 1993; Brand et al., 1994), whose secreted effectors are enriched for post-exponentially (Franco et al., 2009) as are components of the flagellar system (Byrne and Swanson, 1998; Albert-Weissenberger et al., 2010). In addition, the most abundant protein in the outer membrane of L. pneumophila (OmpS) is cross-linked by inter-chain disulfide bonds, forming high molecular weight complexes that are covalently anchored to the underlying peptidoglycan (Butler and Hoffman, 1990). The OmpS disulfide-bonds are susceptible to the action of strong reducing agents (sensitive to alkylation by iodoacetamide) and can reform following removal of the reducing agent with no deleterious effect on viability (Butler et al., 1985; Butler and Hoffman, 1990). Proteins associated with assembly of OmpS monomers into multimeric complexes or with maintenance of disulfide bonds among the subunits are not known.

In E. coli and other Gram negative bacteria, the extracytoplasmic formation of disulfide bonds in proteins is catalyzed by disulfide bond oxidoreductases such as DsbA (Bardwell et al., 1991; Heras et al., 2009). DsbA-catalyzed disulfide bond formation is required for activation of enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase (Bardwell et al., 1991), for the assembly of secreted virulence factors such as pertussis and cholera toxins (Peek and Taylor, 1992; Stenson and Weiss, 2002) and for the assembly of fimbrial adhesins and components of flagella motors (Peek and Taylor, 1992; Zhang and Donnenburg, 1996; Dailey and Berg, 1993). DSB oxidoreductases of the DsbA type introduce disulfide bonds in periplasmic proteins while DSB isomerases, represented by DsbC enzymes, reduce inappropriately formed disulfides to facilitate proper oxidative folding of proteins (Heras et al., 2009). While members of the dsbA family are not essential for viability, their function is required for virulence in many bacteria (Heras et al., 2009; Kadokura and Beckwtih, 2010). In E. coli, DsbA is re-oxidized by membrane spanning DsbB that is part of the electron transport chain, while DsbC is reduced by membrane spanning DsbD which in turn is reduced by cytoplasmic thioredoxin reductase (Heras et. al., 2009; Kadokura and Beckwith, 2010). Analysis of whole genomic sequences of L. pneumophila strains reveals DSB orthologs including: DsbA, DsbB, DsbD, and a gene involved with cytochrome c biogenesis termed DsbE, but no orthologues of DsbC or DsbG. DsbE and DsbD were discovered in virulence and differential essentiality screens (Conover et al., 2003; Viswanathan et al., 2002), but only DsbE has been extensively studied (Viswanathan et al., 2002). The role of redox- active disulfide bond oxidoreductases and isomerases in the assembly and activation of extracytoplasmic proteins associated with differentiation and virulence have not been examined in L. pneumophila.

In this report we explore the role of periplasmic DsbA-like oxidoreductases in assembly of outer membrane proteins and extracytoplasmic virulence factors. Our studies will show that deletion of dsbA (dsbA1) previously annotated in L. pneumophila (absent in the genome of close relative C. burnetii), retains both motility and infectivity for amoeba and cell-based models, and otherwise exhibits no quantifiable phenotypes. A search for other dsbA-like genes identified a gene encoding a 27 kilodalton outer membrane protein of unknown function related to Coxiella outer membrane protein 1 (Com1) of C. burnetii that contained a CXXC motif typical of members of the thioredoxin superfamily. Based on demonstrated oxidoreductase activity, cellular location and protein structural criteria, we named the protein DsbA2. Unlike dsbA1, dsbA2 appeared to be essential for viability.

To advance functional studies of DsbA2 and based on related studies of DsbA in E. coli (Kadokura et al., 2004; Kadokura et al., 2005), we expressed a DsbA2 P198T cis-proline mutant protein in L. pneumophila which exhibited a dominant negative effect on DsbA2 function. By exploiting this dominant negative phenotype, we provide evidence to support a role for DsbA2 in the proper assembly and function of the Dot/Icm T4SS as well as for motility. Our studies not only assign a biological function to the 27-kDa Com1 family of proteins as disulfide bond oxidoreductases, but suggest from phylogenetic analysis that the DsbA2 linage is conserved among those bacteria, with a few exceptions (Bordetella spp. and Helicobacter pylori), expressing T4SS.

Results

Genetic analysis of DsbA alleles

Analysis of the sequenced genomes of L. pneumophila strains revealed an orthologue of the dsbA gene of E. coli (lpg0123 in Philadelphia-1 strain) (see Fig. 1A). A deletion mutant was constructed by vector-free allelic replacement mutagenesis (Chalker et al., 2001) with a Gentr cassette in L. pneumophila strain 130b (AA100ΔdsbA1). This mutant was indistinguishable from wild type strain AA100 by growth in vitro, and in an Acanthamoeba castellanii infection model. Since loss of motility is a common phenotype of dsbA mutants (Dailey and Berg, 1993), we examined stationary phase bacteria for motility by wet mount as described by Swanson (Byrne and Swanson, 1998). In contrast to dsbA mutants of E. coli, the AA100ΔdsbA1 mutant exhibited no defect in motility. Our studies, while not exhaustive, found no phenotypes attributable to the dsbA1 mutant and further studies of this mutant were not pursued.

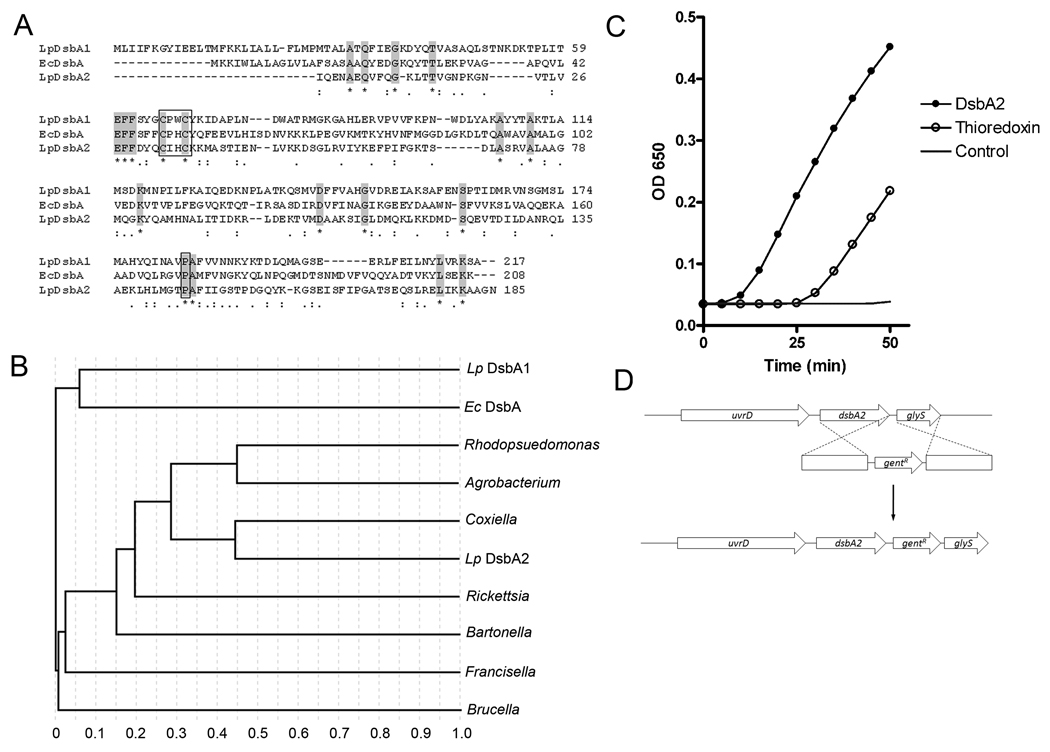

Fig. 1. Phylogenetic analysis and thioredoxin activity of DsbA2 (Lpg1841).

(A) Amino acid sequence alignments: L. pneumophila AAU26230.1 (Lp DsbA), E. coli CAA56736.1 (Ec DsbA), and L. pneumophila YP_095867.1 (Lp DsbA2). Conserved amino acids are highlighted; active site CXXC and conserved cis-proline residues are boxed. (B) ClustalW phylogenetic analysis delineates a sub-set of DsbA-like oxidoreductases present in several T4SS containing bacteria. Strains listed in Fig. 1A above and Rhodopseudomonas palustris NP_946373.1 (Rhodopseudomonas), Agrobacterium tumafaciens AAK87124.1 (Agrobacterium), Coxiella burnetti BAA20499.1 (Coxiella), Rickettsia typhi YP_067376.1 (Rickettsia), Bartonella henselae YP_033613.1 (Bartonella), Francisella tularensis YP_170079.1 (Francisella), and Brucella melitensis NP_540478.1 (Brucella). All proteins contain CxxC active site and conserved cis-proline. (C) Precipitation of insulin was followed spectrophotometrically after the addition of 1 µM thioredoxin (open circles), 5 µM DsbA2 (dark circles), or no enzyme, DTT control (no symbol). A representative experiment is shown. (D) Genetic organization of the dsbA2 locus and allelic replacement strategy to introduce a gentamicin cassette downstream of dsbA2. Insertions within dsbA2 were not obtained and considered lethal.

Since it is not uncommon for bacteria to contain multiple dsbA alleles (Tinsley et. al., 2004; Jarrot et. al., 2010), we re-examined the genomes of L. pneumophila strains for related genes. A PSI BLAST search for proteins containing the conserved CXXC thioredoxin fold common to members of the DsbA family identified a gene encoding a 27- kDa outer membrane protein (lpg1841 in Philadelphia-1) that is closely related to the Com1 (Coxiella outer membrane) protein of C. burnetii (Hendrix et al., 1993) as a potential DsbA candidate. As seen in Fig 1A, the Com1-like protein exhibited little similarity in amino acid sequence with LpDsbA1 and EcDsbA proteins, but showed alignments of key residues in the CXXC thioredoxin motif and in a cis conformation proline region that are common to and required for DsbA function (Kadokura et al., 2004; Kadokura and Beckwith, 2010). These functional alignments were also observed with Phyre software by threading Com1onto the EcDsbA crystal structure (data not shown). Interestingly, the Com1 protein of L. pneumophila had been previously identified in a 2D gel proteomic screen of proteins enriched for in differentiated cyst forms (compared to stationary phase forms) of L. pneumophila (Garduno et al., 2002). Phylogenetic analysis (see Fig. 1B) indicated that Lpg1841 was more closely related to a family of Com1/DsbA-like proteins found in Agrobacterium tumifaciens, Francisella tularensis, C. burnetii, Rickettsia sp, and other bacteria than to DsbA of E. coli. Based on structural alignments of key functional elements with the DsbA of E. coli, we annotated Lpg1841 as DsbA2. It is noteworthy that, with the exception of Bordetella spp. and Helicobacter pylori, the DsbA2 lineage appears to be conserved in, but limited to, those bacteria expressing T4SS.

DsbA2 functional activity

To test for thiol oxidoreductase activity, recombinant His6-tagged DsbA2 was purified from E. coli by Ni-interaction chromatography. In an insulin-based precipitation assay in the presence of dithiothreitol, recombinant DsbA2 accelerated the reduction disulfide bonds recorded spectrophotometrically as an increase in precipitation of insoluble insulin subunits with time (Holmgren, 1979) (see Fig. 1C). Thioredoxin (positive control) also catalyzed the reduction of disulfide bonds in insulin. While DsbA2 exhibits disulfide bond oxidoreductase activity, this assay does not distinguish between oxidase and reductase function.

dsbA2 appears to be essential

In L. pneumophila, dsbA2 is flanked by uvrD (upstream) and glyS (downstream). Promoter elements identified in the intergenic region suggest that dsbA2 is likely transcribed independently of uvrD. Using a vector-free allelic-replacement mutagenic strategy as described for producing deletions of dsbA1, we set out to delete dsbA2. However, we were unable to isolate dsbA2 deletion mutants in either AA100 or Lp02 genetic backgrounds. A second strategy involved cloning of flaking regions of dsbA2 (replaced with kanamycin cassette) into suicide vector pRDX (Morash et al., 2009) and following electroporation into Lp02 or AA100 strains, the bacteria were plated for selection on Km-containing BCYE medium. Selected Kmr colonies were scored for resistance to metronidazole and susceptibility to chloramphenicol that indicate loss of vector and allelic replacement. No colonies displayed the correct phenotypes indicating that allelic replacement had not occurred. We were, however, able to introduce a gentamicin cassette downstream of the coding sequence of dsbA2, diminishing the possibility of polar effects on the expression of downstream genes (see Fig. 1D). Moreover, attempts at trans-complementation of a genomic deletion with a plasmid-borne copy of dsbA2 were also unsuccessful, consistent with our previous experience with both essential genes (LeBlanc et al. 2008, Hoffman et al., 1992b) and genes that become conditionally lethal in certain mutant backgrounds (LeBlanc et al., 2006). Additionally, since some Dot/Icm mutants display conditional lethality depending on functional status of Dot/Icm system (Conover et al., 2003), we also attempted to construct a dsbA2 knockout mutation in a dotA mutant, without success. Taken together, these studies suggest that DsbA2 provides an essential function in L. pneumophila; whereas, DsbA1 is nonessential and without phenotype. It is also noteworthy that an orthologue of DsbA1 is absent from the genome of close relative C. burnetii.

DsbA2 is not an outer membrane protein

DsbA2 is annotated in databases as a 27-kDa protein of unknown function, based on a prior report that Com1 of C. burnetii is an immunodominant outer membrane protein (Hendrix, et al., 1993). Since DsbA-like proteins typically reside in the periplasm of Gram negative bacteria (Tinsley et al., 2004) we next investigated its cellular location. In silico analysis of the primary amino acid sequence of DsbA2 identified a sec-dependent leader sequence typical of DsbA proteins (PSORTb v3.0) (Yu et al., 2010) and predicted with high confidence a periplasmic location (score of 9.84 and similar to that predicted for DsbA1). To confirm a periplasmic location, whole cell extracts were subjected to cellular fractionation protocols routinely used to localize proteins in L. pneumophila (Butler et al., 1985, Lema et al., 1988, Matthews and Roy, 2000; Vincent et al., 2006). To identify DsbA2 in these fractions, monospecific mouse polyclonal antibodies raised against purified His6-tagged DsbA2 protein (no cross-reactivity with DsbA1) was used. As a control, antibodies against periplasmic protein LepB, cytosolic protein IHF, and outer membrane protein OmpS were used (Butler et al., 1985; Vincent et al., 2006; Morash et al., 2009). As depicted in Fig. 2A, DsbA2 was distributed between the soluble fraction (Lane S) (cytoplasmic and periplasmic proteins) and in the Triton-soluble fraction (Lane E: inner membrane), but was absent in the Triton-insoluble fraction (Lane N: outer membrane). As a control for the cytoplasmic fraction, IHF was exclusive to the soluble fraction whereas LepB, a periplasmic protein was associated with the Triton-soluble fraction. The major outer membrane protein OmpS was present in the Triton-soluble as well as the Triton-insoluble fractions as noted previously (Vincent et al., 2006). If DsbA2 were a lipoprotein, it would have been located in the Triton-soluble fraction as was LepB. Our studies therefore support a periplasmic location for DsbA2.

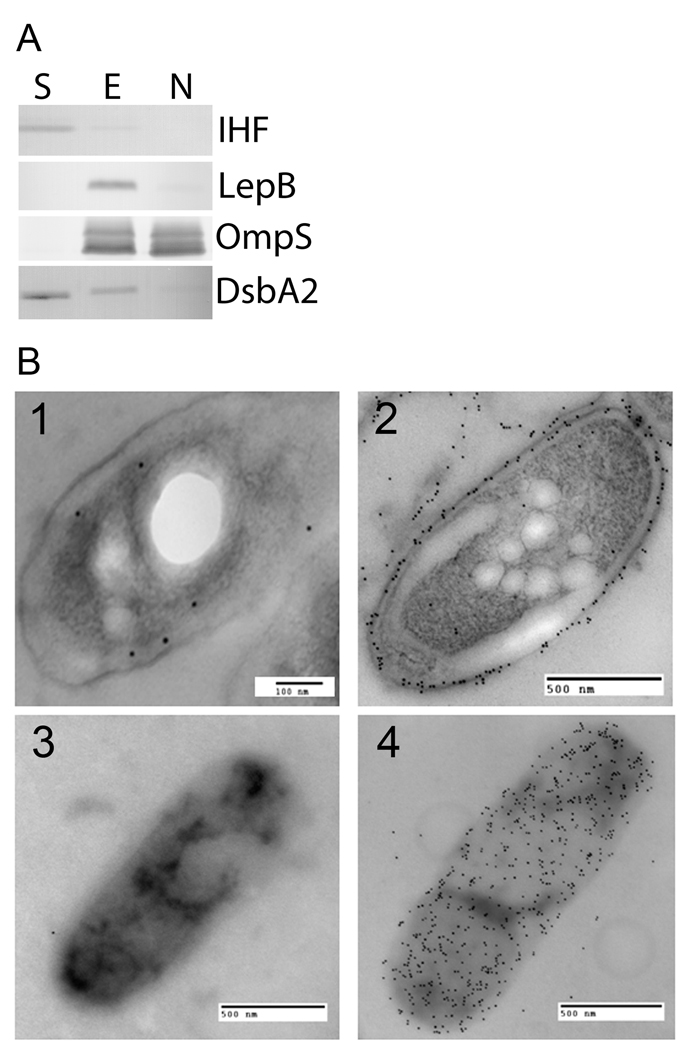

Fig. 2. DsbA2 is not an outer membrane protein.

(A) DsbA2 partitions into the soluble phase after Triton X-100 separation. Whole-cell lysates of L. pneumophila were cleared by low-speed centrifugation (10,000 × g), and membrane material was pelleted by ultra-centrifugation (100,000 × g). The Triton-extractable inner membrane proteins (Lane E) were re-suspended in 1% Triton X-100, and the Triton-insoluble outer membrane proteins (Lane N) were re-pelleted by ultra-centrifugation. Equivalent protein amounts were loaded in all lanes, and to ensure fraction separation, a known soluble phase protein (IHF), inner membrane protein (LepB), and outer membrane protein (OmpS) were included as controls for the soluble (S), inner membrane (E), and outer membrane protein (N) fractions, respectively. (B) Immunogold electron microscopy of ultrathin sections and whole cells of L. pneumophila. Panels 1 and 3 are developed with DsbA2 primary antibody and 10 nm gold conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies, while Panels 2 and 4 are developed with OmpS-specific antibody and 10 nm gold conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies. Counting procedures (detailed in the Methods) indicate that DsbA2 is located in the periplasm 63% of the time with 95% confidence. The DsbA2-specific antibody does not cross react with DsbA1.

To confirm that DsbA2 is not an outer membrane protein, immunogold electron microscopy of ultra-thin sections of L. pneumophila were analyzed. As seen in Fig. 2B panel 1, sections probed with DsbA2-specific antibodies indicated that gold particles (10 nm gold conjugated to goat anti-mouse or rabbit immunoglobulin) were predominantly periplasmic, residing there 63% of the time with a 95% confidence interval based on the method of Mallette (Mallette, 1969) and previously validated as described (Garduno et al. 1998c). As seen in Fig. 2B, panel 2, immunogold labeling with OmpS-specific antibodies shows gold particles associated with the outer membrane. As a further test for whether DsbA2 localizes to the bacterial surface, whole cell surface labeling with DsbA2-specific antibody (panel 3) or OmpS-specific antibody (panel 4) indicated that DsbA2 is not located on the surface of L. pneumophila. These results, together with the cellular localization studies, establish that DsbA2 is located in the periplasm and not in the outer membrane.

Redox status of periplasmic DsbA2

We next assessed the redox status of periplasmic DsbA2 by AMS alkylation and immunoblot with whole cells of L. pneumophila collected in early stationary phase. DsbA proteins are typically maintained as the disulfide by DsbB which oxidizes reduced DsbA and is itself oxidized by the electron transport chain (Kadokura and Beckwith, 2010). As seen in Fig. S1, lane 1, AMS fully alkylated DsbA2 in cells pretreated with 10 mM DTT to reduce all disulfide bonds. Lane 2 depicts untreated DsbA2 that runs at a lower molecular weight (non-alkylated). AMS treatment of whole cells (Lane 3) revealed that DsbA2 redox status is mixed (60% thiol and 40% disulfide), similar to the E. coli DsbA where the oxidized form is slightly favored (Kadokura et al., 2004). While many factors likely influence the relative redox status of periplasmic proteins, our findings are consistent with an oxidase function.

DsbA2 dominant negative mutants inhibit intracellular replication

Advancing functional studies of essential genes is often dependent on genetic systems that can control promoter function so that phenotypic changes can be correlated with levels of gene expression (Msadek, 2009). Alternatively, dominant negative phenotypes can sometimes be produced through mutations that alter function of the gene product in ways that interfere with the function of the native protein. We noted from in silico structural analysis of DsbA2 that the thioredoxin fold and a key cis-proline residue near the CXXC domain were highly conserved. We reasoned that it might be possible to create similar functional mutations in DsbA2 based on analogous mutant constructs in DsbA of E. coli (Kadokura et al., 2004 and Kadokura et al., 2005) and in thioredoxin (Motohashi et al., 2001). In this regard, site directed mutagenesis was used to change the second cysteine residue in the active CXXC site to serine (C89S), which was used to capture substrate proteins by thioredoxin (Motohashi et al., 2001) and by DsbG in E. coli (Depuydt et al., 2009). This mutation renders the protein incapable of catalyzing oxidative protein folding. A second mutation in DsbA proteins changes a conserved cis-proline residue at position 198 in DsbA2 to threonine (P198T) (see Fig. S2). P198T is predicted to stabilize disulfide bonds between enzyme and protein substrates (Kadokura et al., 2004), but not with its dedicated oxidant DsbB.

To assess whether expression of C89S or P198T mutant proteins in L. pneumophila strain AA100 were deleterious for growth, the genes encoding C89S and P198T mutant proteins were cloned into the pMMB206 vector that enables control of gene expression by IPTG (Morales et al., 1991). In vitro growth characteristics in BYE broth over a range of IPTG concentrations were monitored. As seen in Fig. S3A, expression of these mutant proteins resulted in no deleterious effects on bacterial growth. To confirm expression of C89S and P198T mutant proteins during in vitro growth, whole cell fractions grown with and without IPTG (0, 0.5, and 5 mM) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot with DsbA2-specific antibody. As seen in Fig. S3B, DsbA2 protein levels increased over time with increasing IPTG concentration as compared with un-induced controls. It is noteworthy, that at 10 h post induction, a doublet can be observed in the P198T panels with the upper band attributed to the recombinant his-tagged protein (Fig. S3B). C89S mutant protein does not contain a His6-tag. These studies established that over expression of these proteins in L. pneumophila had no measurable effects on in vitro growth.

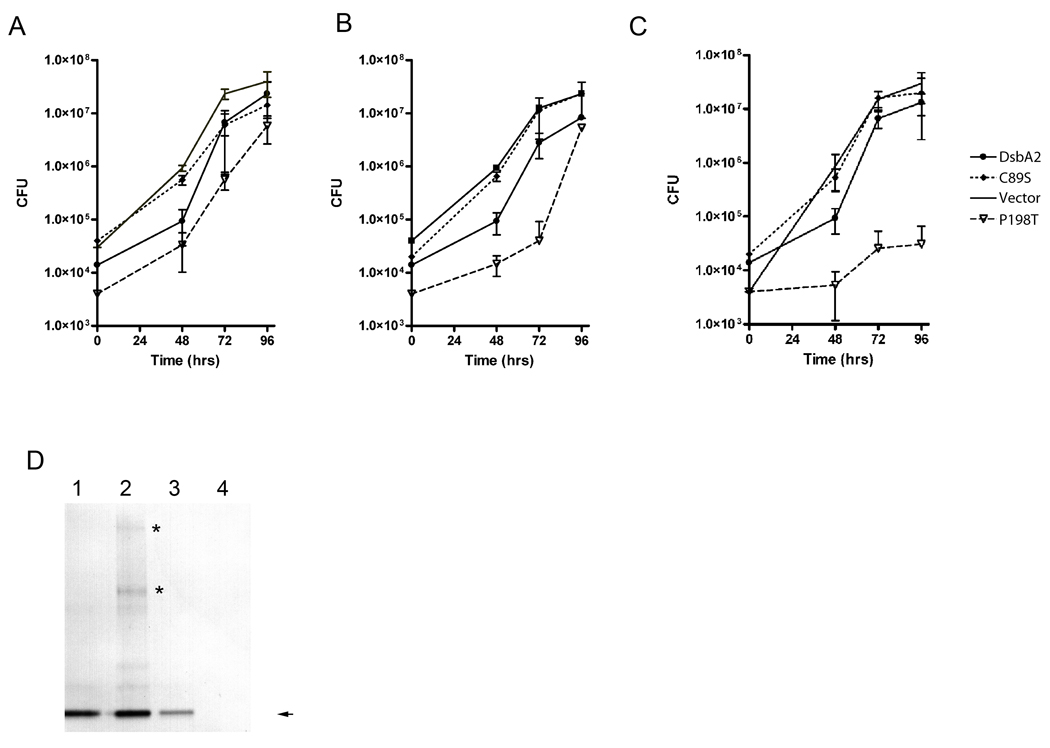

To test whether expression of C89S or P198T mutant proteins might affect periplasmic functions related to virulence, AA100 strains expressing these constructs were pre-induced with 0, 0.5 and 5 mM IPTG and used to infect amoeba. IPTG levels were maintained throughout the infection. As seen in Fig. 3A (un-induced), intracellular growth rates for the C89S and P198T mutant strains and controls (pMMB:dsbA2 and the empty vector), when adjusted for CFU differences at zero time, were not significant. Upon induction with 0.5 mM IPTG (Fig. 3B), the growth rates for the over-expressing wild type (pMMB::dsbA2) and C89S expressing strains were unchanged when compared to the uninduced rates depicted in Fig. 3A. However, the strain expressing the P198T mutant protein exhibited a measurable growth defect out to 48 h post infection. At 5 mM IPTG, the growth defect for the P198T mutant was much more pronounced; whereas, growth rates for strains over-expressing the C89S mutant protein and wild type DsbA2 protein were unchanged when compared with un-induced growth rates (see Fig. 3C). To confirm that mutant proteins were expressed, especially with the C89S mutant, cellular extracts from infected amoeba were analyzed by non-reducing SDS-PAGE and immunoblot. As depicted in Fig. 3D, DsbA2 protein levels were detected in all extracts except for the P198T mutant (5 mM IPTG) lane 4, due to the absence of bacteria in the amoebae. Comparison of protein levels for DsbA2 in lanes 1 and 2 with the vector control (genomic expression of DsbA2) in lane 3 are consistent with IPTG induced over expression. Immuno-reactive bands noted at molecular masses higher than that of DsbA2 for strains over-expressing DsbA2 (lane 1) and particularly for the C89S mutant protein (lane 2; major complexes denoted by asterisks) likely represent captured protein substrates. These experiments demonstrate that over-expression of the P198T mutant protein, but not C89S mutant protein, resulted in a dominant negative effect on intracellular multiplication, supporting a role for DsbA2 function in Legionella pathogenesis.

Fig. 3. Expression of P198T mutant protein inhibits intracellular growth in amoeba.

Acanthamoeba castellanii were infected with L. pneumophila AA100 constructs (A) in the absence of IPTG induction, (B) induction at 0.5 mM IPTG, and (C) at 5 mM IPTG. Colony forming units (cfu) were determined in triplicate at the indicated times in a single experiment: AA100 pMMB:empty (no symbol), DsbA2 (filled circle), DsbA2 C89S (dashed line), or DsbA2 P198T (open triangle). (D) Immunoblot detection of DsbA2 proteins expressed during infection of A. castellenii. Lanes 1. pMMB: DsbA2; Lane 2, pMMB:C89S; Lane 3, pMMB:empty; and Lane 4, pMMB:P198T. DsbA2 at 30 kDa is indicated by the arrow. SDS PAGE was run under non-reducing conditions and higher molecular weight complexes than DsbA2 can be seen in bacteria expressing wild type DsbA2 (Lane 1) and C89S (Lane 3) that disappear under reducing conditions (data not shown). Asterisks denote bands unique to the C89S mutant.

DsbA2 P198T expression affects invasion of HeLa cells

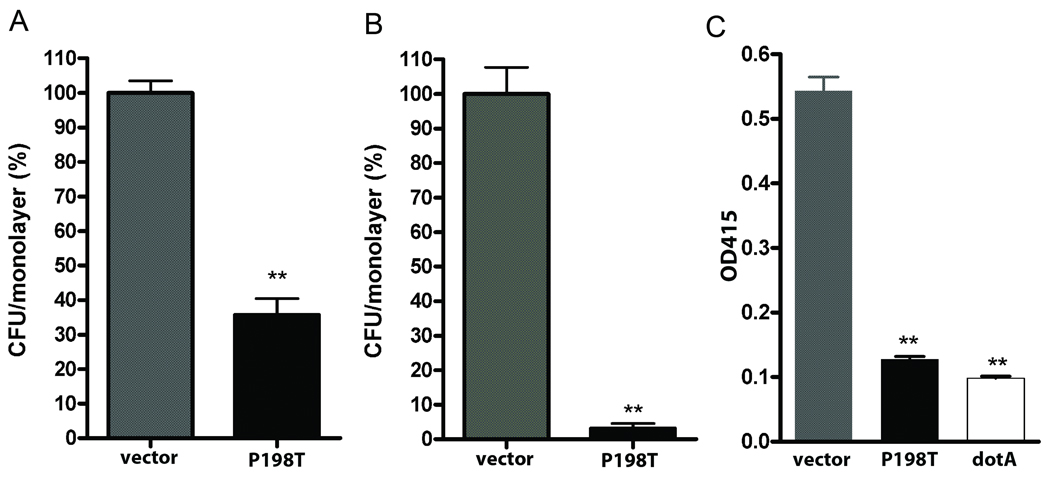

Since amoebae are naturally phagocytic, it was not possible to distinguish whether the dominant negative effect on intracellular growth was due to defects in primary attachment or in invasion. To address these possibilities a HeLa cell invasion model was used (Garduno et al., 1998b; McCusker et al., 1991; Newton et al., 2008). As seen in Fig. 4A and 4B, L. pneumophila strain AA100 pMMB:empty vector under inducing conditions readily attached to and invaded HeLa cells, while the P198T-expressing mutant exhibited a 60% reduction in attachment efficiency and nearly 90% decrease in internalization. These findings are consistent with previous reports that multiple surface proteins mediate attachment, while only Hsp60 (HtpB) whose surface location and function is dependent on a functional Dot/Icm T4SS mediates invasion of HeLa cells (Garduno et al., 1998a).

Fig. 4. Expression of P198T mutant protein inhibits infectivity of HeLa cells and contact lysis of erythrocytes.

Effects of P198T expression on attachment to and invasion of HeLa cell monolayers. (A) Attachment of AA100 expressing P198T (black) to HeLa cells was reduced by 60% compared with the empty vector control (grey). (B) Invasion of HeLa cells (gentamicin treatment) by AA100 P198T (black) was decreased by >90% compared to the empty vector control (grey). (C) Erythrocyte contact lysis assay. Erythrocyte lysis was measured at A450 with the AA100 (empty vector) control (grey), AA100 expressing P198T (black) and a dotA mutant that is defective in T4SS (white). ** denotes statistical significance of < 0.05 by student t-test.

DsbA2 P198T dominant negative effect on Dot/Icm function

Since a functional Dot/Icm T4SS is essential for invasion and intracellular multiplication of L. pneumophila in host cells (Brand et al., 1994; Berger and Isberg, 1993; Franco et al., 2009), we considered it likely that the dominant negative effect of the P198T mutant protein was due to interference with either assembly or function of the Dot/Icm secretion apparatus. To directly test this possibility, we employed a well established contact hemolytic assay that was previously validated with specific Dot/Icm mutants (Kirby et al., 1998; Charpentier et al., 2009). In this assay, AA100 pMMB:empty vector mediated lysis of erythrocytes (see Fig. 4C). In contrast, bacteria expressing the dominant negative P198T mutant protein did not exhibit contact-dependent hemolysis, which was equivalent to that of a ΔdotA mutant control (Fig. 4C). Longer incubations (>24 hrs) also showed no erythrocyte lysis by bacteria expressing P198T (data not shown). Whether P198T mutant protein exhibits a dominant negative effect on other secretion systems was not investigated, though Zn-metalloprotease activity, a type II secretion system indicator (Rossier et al., 2008; Keen and Hoffman, 1989) was unaffected relative to controls (data not presented). We suggest that the dominant negative avirulence phenotype of the P198T mutant protein most likely results from disruption of assembly or function of the Dot/Icm T4SS.

DsbA2 function is required for flagella assembly

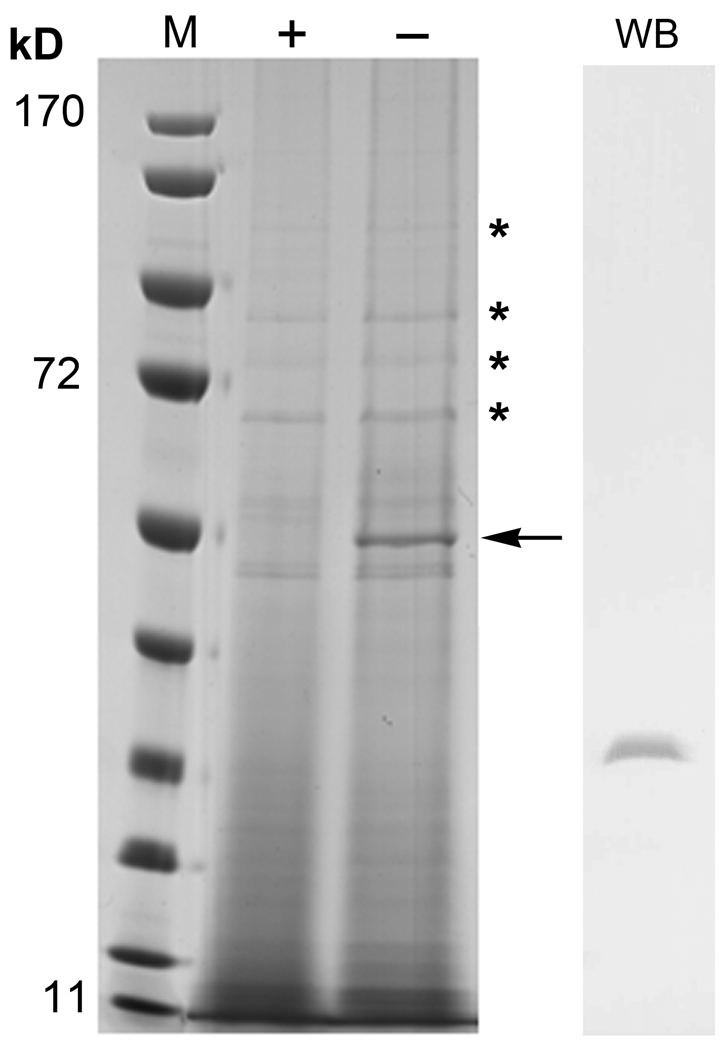

In earlier studies we observed that a dsbA1 mutant retained motility. To test whether DsbA2 function was required for motility, we examined wet mounts of stationary phase bacteria (AA100 P198T) grown under inducing and non-inducing conditions. Bacterial motility (wet mounts viewed microscopically) was evident for the P198T mutant grown under non-inducing conditions. The same strain grown to the same OD under IPTG inducing conditions was nonmotile. To confirm the presence or absence of flagella as well as other proteins, induced and uninduced bacteria were subjected to osmotic shock in Tris-EDTA buffer (Kadokura, et al., 2004) and following centrifugation to remove whole bacteria, the shockates were precipitated with TCA and examined by SDS-PAGE. As seen in Fig. 5, a prominent 55 kDa protein was notably absent from bacteria expressing P198T mutant protein. The 55 kDa protein was verified as flagellin (fliC or flaA) by MALDI-ToF MS with high confidence, as most major ions were mapped to this protein. Whether P198T mutant protein affects oxidative folding of flagellin monomers or proteins associated with the motor as noted with dsbA mutants of E. coli was not pursued. While not the focus of this particular experiment, P198T mutant protein was detected in the shockate fraction by western blot (see Fig. 5, WB). Taken together, these studies indicate that DsbA2 function, and not that of DsbA1, is required for both motility and Dot/Icm function.

Fig. 5. Expression of P198T mutant protein inhibits flagellar synthesis.

Coomassie stained SDS PAGE of the osmotic shockate from the AA100 P198T mutant strain after induction with 1 mM IPTG (+) or uninduced (−). The 55 kDa band noted by the arrow in the uninduced lane and absent from the induced lane was identified as flagellin by MALDI TOF MS. * indicate periplasmic proteins that are identical between induced and uninduced conditions. Lane M denotes molecular weight markers in kilodaltons (kD). WB is a western blot with DsbA2-specific antibody indicating that DsbA2 is present in the shockate.

DsbA2 P198T mutant protein competes with DsbA2 protein in vitro

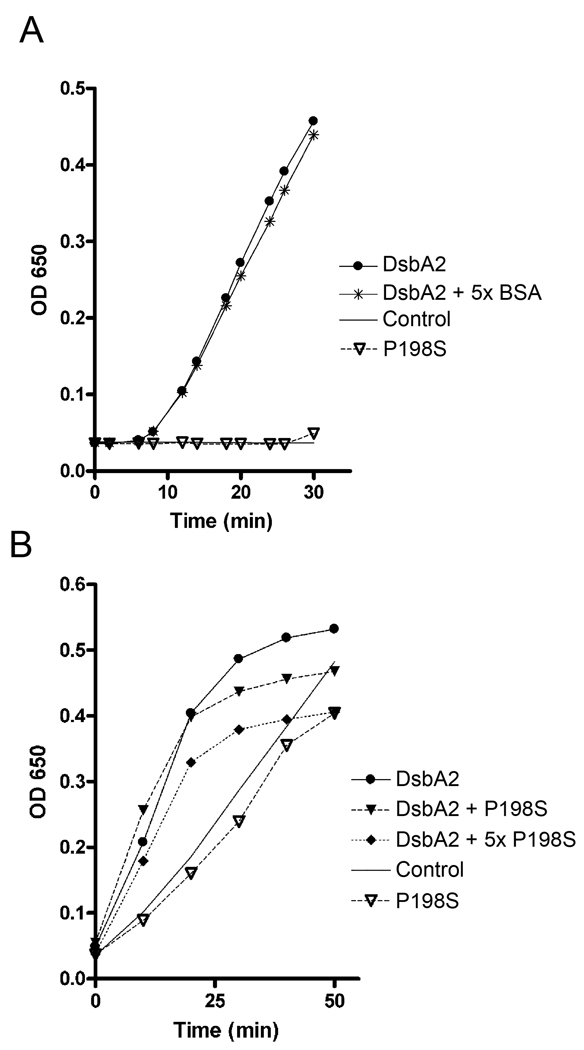

Our studies suggest that the dominant negative effect of the P198T mutant protein results from interference with wild type DsbA2 activity. To directly test this hypothesis we employed a modified insulin reduction assay. We first determined whether the P198T mutant protein retained oxidoreductase activity and as seen in Fig. 6A, it did not catalyze reduction of insulin when compared to functional DsbA2 and a DTT control. Even extending the assay for several hours did not enable P198T catalyzed insulin precipitation to increase above that of DTT controls. Since the P198T mutant protein is predicted to form stable disulfide bond complexes with substrate proteins, we considered the possibility that such complexes might ablate insulin precipitation. To test this possibility, P198T mutant protein was added to the insulin assay to evaluate effects on DsbA2 activity. As seen in Fig. 6B, increasing concentrations of P198T mutant protein partially inhibited wild type enzyme activity by appearing to limit available substrate to DsbA2, consistent with the notion that the mutant protein formed disulfide bonded complexes with insulin. An alternative possibility that might explain these results is that P198T mutant protein nonspecifically contributed to the solubility of reduced insulin proteins. To rule this out, comparable concentrations of bovine serum albumin (5xBSA) were added to the DsbA2 insulin reduction assay. BSA concentrations had no effect on the reaction (See Fig. 6A). These results suggest that while P198T mutant protein lacks enzymatic activity, it appears to interfere with DsbA2 activity, possibly by forming stable complexes with insulin.

Fig. 6. DsbA2 P198T inhibits DsbA2 activity in a modified insulin reduction assay.

(A) DsbA2 P198T (5 µM, open triangle) has no activity greater than control (solid line) in the insulin reduction assay. DsbA2 activity in this assay (solid circle) is not affected by addition of 25 µM BSA (star). (B) Modified insulin reduction assay (see text): Insulin precipitation by 5 µM DsbA2 (black circle) and competition with 5 µM (dark dashed triangles) or 25 µM P198T (dark dashed diamonds) mutant protein. As noted in panel A, P198T (open triangle) displayed no activity over that of the DTT control (solid line). The dose dependent effect of the P198T mutant protein on DsbA2 activity is consistent with the possibility that the mutant protein, by binding insulin, has a rate limiting effect on the activity of DsbA2. These experiments were repeated three separate times, representative experiment shown.

DsbA2P198T traps substrate proteins in L. pneumophila

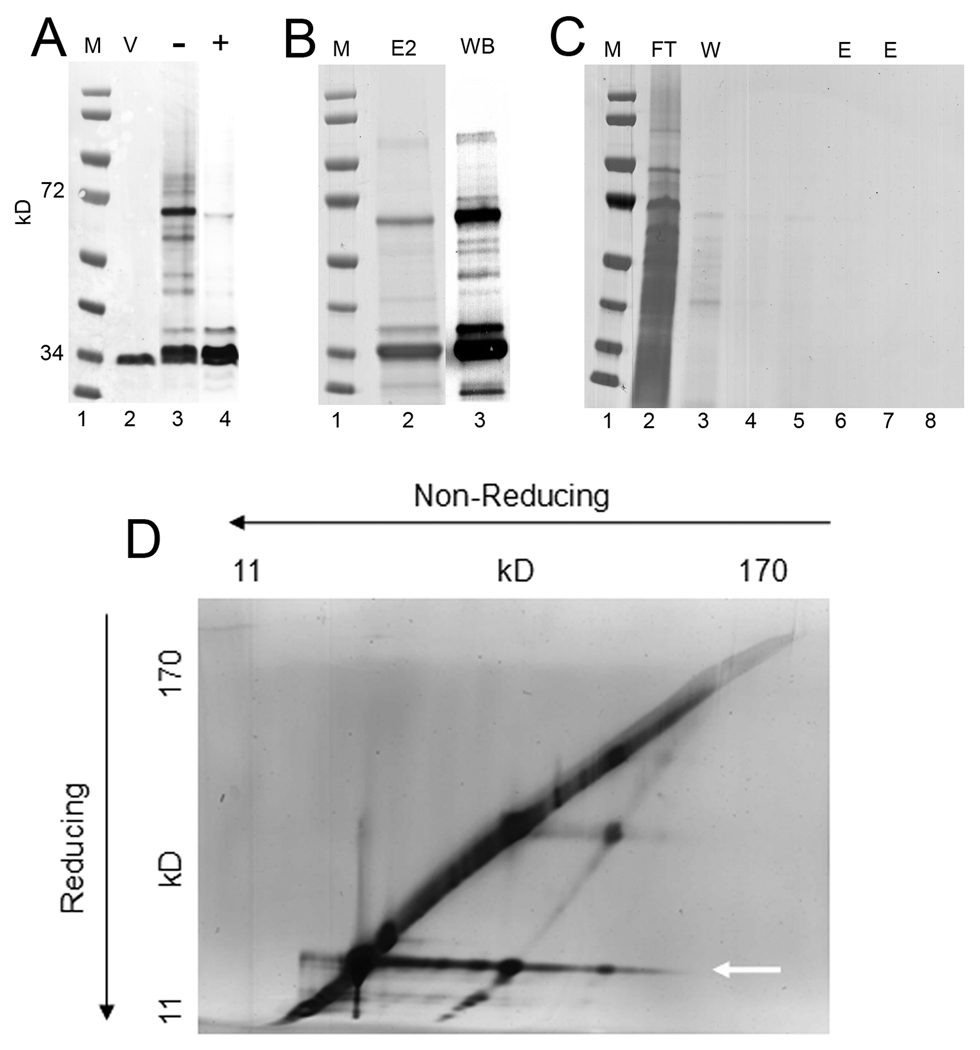

Based on the in vitro insulin assay results and work of others (Kadokura, et al., 2004), we considered the possibility that P198T mutant protein might form stable complexes with DsbA2 substrate proteins in L. pneumophila and enable their identification. To test this possibility, protein complexes obtained from AA100 strains grown in the presence or absence of IPTG were analyzed by non-reducing SDS PAGE and immunoblot for P198T-substrate complexes. As seen in Fig. 7A, protein complexes of higher molecular weight than His-tagged P198T were not observed in extracts from un-induced bacteria (lane 2). In contrast, immuno-reactive proteins of higher molecular weight were detected under inducing conditions (lane 3) and are indicative of captured substrates. These complexes disappeared under reducing conditions as shown in Fig. 7A, lane 4, consistent with reduction of cross-linking disulfide-bonds. To ensure that the proteins noted were indeed cross-linked to P198T mutant protein, His6-tagged P198T protein-complexes were affinity purified by nickel (Ni++) interaction chromatography and the pattern of high molecular weight complexes resolved by non-reducing SDS-PAGE and immunoblot were similar to those depicted in Fig. 7A (see Fig. 7B). As a control for nonspecific binding of L. pneumophila proteins to the Ni++ column, equivalent extracts from the vector control strain AA100 were analyzed and as depicted in Fig. 7C (lanes 5–8), no proteins were captured. We chose not to pursue further experiments with the C89S mutant protein at this time because proteins captured by the free thiol likely differ from those substrates captured by oxidative disulfide bond formation by DsbA2.

Fig. 7. Substrate-protein capture by P198T-mutant protein in L. pneumophila.

(A). Immunoblots (DsbA2 antibodies) of whole cell lysates subjected to SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions or as indicated: Lane 1 MW markers; Lane 2, AA100 pMMB:P198T un-induced whole cell lysates; Lane 3 AA100 pMMB:P198T induced with 1 mM IPTG; Lane 4, same as Lane 3 except run under reducing conditions (note disappearance of higher molecular weight complexes). (B) His6 DsbA2-substrate complexes enriched for by Ni++ column chromatography and separated by non-reducing SDS PAGE: Coomassie stain (E2, lane 2), and DsbA2 western blot (WB, lane 3). (C) Control NI++ column of AA100 lysate, flow through (FT, lane 2), washes (W, lane 3–5), and elutions (E, lanes 6–8) show that there is negligible non-specific binding of Legionella proteins to the nickel column. (D) AA100 pMMB:P198T was induced in vitro and His6-tagged DsbA2 P198T substrate complexes were purified by Ni++ chromotography. Diagonal gels of captured proteins were run under non-reducing (direction of electrophoresis indicated by arrows), then reducing conditions. Protein spots (silver stained) off the diagonal are DsbA2 interacting proteins whose disulfide bridge had been reduced in the second dimension. The identities of these proteins by MS are listed in Table 2. Arrow points to DsbA2 that has dissociated from interacting proteins in the second dimension.

To identify substrate proteins, Ni++ affinity-purified P198T complexes were run on SDS PAGE diagonal gels (Hoffman et al., 1992a; Kadokura et al., 2004) with the first dimension non-reducing and the second dimension under reducing conditions that dissociate disulfide-bond cross-linked complexes. As seen in Fig. 7D, dissociated proteins running off the diagonal are indicative of captured proteins. The extended band noted by arrow at ∼30 kDa is P198T protein. Proteins running off the diagonal line were identified by MS-MS and yielded almost exclusively periplasmic and membrane-associated proteins, including several virulence factors, all of which contained cysteine residues with the one exception being HtpA (Table 2). Some important captured substrates included: Dot/Icm T4SS core structural proteins DotC, DotG, and DotK and IcmX; the periplasmic and surface localized invasin HtpB (Hsp60) and its co-chaperone HtpA (Hsp10) which lacks cysteine; and subunits of OmpS of the MOMP complex. While some of the captured proteins are indicated as cytoplasmic based on PSORTb predictions, this does not necessarily exclude a periplasmic location. It is important to note that other Dot/Icm proteins that do not contain cysteine residues (DotD, DotF, IcmW and IcmY) or cytoplasmic proteins that do contain cysteine residues (isocitrate dehydrogenase) were not captured in these studies. Finally, the Dot/Icm proteins captured through interaction with P198T mutant protein are considered essential for assembly and function of the T4SS (Vincent et al., 2006). Further study will be required to determine whether any of the captured substrates are essential for viability. These studies support a functional role for DsbA2 in the oxidative folding of proteins destined for assembly into the Dot/Icm T4SS.

Table 2.

DsbA2 Interacting Proteins

| Protein | Accession | Localized | Size | Reference | Cysteines |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IcmE (DotG) | gi52840696 | OM | 108 kDa | Vogela | 16 |

| Major Outer Membrane Protein | gi52843155 | OM | 32 kDa | Hoffmanb | 4 |

| DotC | gi52842881 | OM | 34 kDa | Vogel | 2 |

| HtpB (GroEL) | gi52840925 | P/OM | 58 kDa | Hoffmanc | 4 |

| cytochrome c oxidase | gi52843092 | IM | 45 kDa | predicted | 4 |

| Sensory transduction system | gi52840618 | IM | 24 kDa | predicted | 1 |

| aspartate kinase/decarboxylase | gi52842038 | C | 95 kDa | predicted | 12 |

| DnaJ | gi52842241 | C/P | 41 kDa | predicted | 10 |

| Dioxygenase | gi52842491 | C | 41 kDa | predicted | 5 |

| LPS biosynthesis protein | gi52840985 | C | 54 kDa | predicted | 7 |

| penicillin binding protein 1A | gi52841160 | IM | 89 kDa | predicted | 2 |

| Glu/Leu/Phe dehydrogenase | gi52842489 | C | 38 kDa | predicted | 3 |

| co-chaperonin HtpA (GroES) | gi52840924 | IM | 10 kDa | Hoffman | 0 |

| aminopeptidase | gi52843010 | OM | 47 kDa | predicted | 6 |

| cell-division protein FtsA | gi52842816 | C | 45 kDa | predicted | 8 |

| membrane protein YdgA-like | gi52840785 | OM | 55 kDa | predicted | 1 |

| hypothetical lpg1994 | gi52842211 | OM | 45 kDa | predicted | 2 |

| S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase | gi52842238 | C | 49 kDa | predicted | 8 |

| hypothetical lpg2327 | gi52842537 | C | 34 kDa | predicted | 2 |

| malate dehydrogenase | gi52842562 | Unk | 36 kDa | predicted | 6 |

| hypothetical 2519 | gi52842727 | Unk | 21 kDa | predicted | 2 |

| IcmX | gi52842895 | IM | 51 kDa | predicted | 3 |

| EnhA | gi52840941 | OM | 23 kDa | predicted | 7 |

| DotK | gi52840692 | OM | 21 kDa | Vogela | 3 |

| D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase | gi52841739 | IM | 48 kDa | predicted | 2 |

| SCO1/SenC family (thioredoxin-like) protein | gi52840658 | Unk | 24 kDa | predicted | 2 |

| hypothetical protein lpg0732 | gi52840969 | OM | 23 kDa | predicted | 1 |

| hypothetical protein lpg1585 (similar EnhB) | gi52841815 | OM | 18 kDa | predicted | 4 |

| 16kD immunogenic protein | gi52841943 | OM | 16 kDa | predicted | 3 |

| alkylhydroperoxide reductase | gi52842560 | C | 24 kDa | predicted | 3 |

Discussion

Here we report that a 27-kDa outer membrane protein of unknown function is a member of the DsbA family of oxidoreductases. Based on phylogenetic and functional criteria, as well as confirmation of a periplasmic location, we have named this gene dsbA2. While L. pneumophila contains two genes encoding DsbA-like proteins, dsbA1 mutants were essentially wild type for infectivity of amoeba and exhibited no discernable phenotypes in vitro. To overcome the apparent essentiality of DsbA2, we constructed a P198T mutant that in E. coli DsbA (P151T) formed stable complexes with substrate proteins (Kadokura et al., 2004). In L. pneumophila, expression of the DsbA2 P198T mutant protein produced a dominant negative effect on several virulence phenotypes including: (i) loss of intracellular multiplication in amoeba; (ii) loss of attachment and invasiveness of HeLa cells; (iii) loss of contact (Dot/Icm dependent) lysis of erythrocytes; and (iv) loss of flagella-driven motility. Disruption of the Dot/Icm complex was inferred from the above results and confirmed by capture of DotC, DotG, DotK and IcmX substrates by P198T mutant protein. The abundance and diversity of captured proteins (see Table 2) suggests that L. pneumophila is highly dependent on DsbA2 for oxidative folding of periplasmic proteins, including those destined for assembly into macromolecular structures. These studies not only revealed important biological functions for DsbA2 in L. pneumophila, but also the likelihood that DsbA2 provides similar function in a very broad range on microbes, including many also expressing T4SS.

In retrospect, the original annotation of Com1 as an outer membrane protein was clearly misleading, but not uncommon. In reviewing the history, we note that in silico analysis of the primary amino acid sequence of DsbA2 identified a sec-dependent leader sequence typical of DsbA proteins and predicted with high confidence a periplasmic location (score of 9.84 and similar to that predicted for DsbA1). The periplasmic location was confirmed in our studies by cell fractionation and immunogold electron microscopy. In contrast, the cellular location of Com1 could not be predicted by PSORTb analysis, despite sharing 48% identity and 69% similarity with DsbA2. There was ambiguity in the original communication on the cellular location as recombinant Com1 expressed in E. coli appeared in the Sarkosyl-soluble (inner membrane) fraction, while surface iodination and protinease K treatments of whole C. burnetii cells indicated an outer membrane association (Hendrix et al., 1993). Com1 is an immunodominant antigen of C. burnetii that is useful in the diagnostics of Q fever (Hendrix, et al., 1993), while DsbA2 is not an immunodominant antigen based on screening of convalescent sera from patients with confirmed Legionnaires’ disease (personal communication, Claressa Lucas, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

In addition to the misleading annotation, DsbA2 also differs sufficiently in amino acid sequence from the canonical DsbA that it is now listed by the NCBI as a separate family. Simple BLAST searches with DsbA2 do not capture DsbA, although domain searches with the thioredoxin fold of DsbA2 would have placed it in the thioredoxin super family, but not necessarily in the DsbA family. Most genera expressing DsbA2, like L. pneumophila, also expressed a DsbA (DsbA1) orthologue (the exception being C. burnetii), but without exception all lacked an orthologue of DsbC that provides protein disulfide isomerase activity. Ironically, comparative BLAST searches with E. coli DsbA and DsbA2 (any member of this group) using a cut-off of e−24, will reveal the DsbA2 group to be far more conserved through evolution than the DsbA group. Much of the amino acid conservation noted for DsbA2 members is due to a 50 – 60 amino acid extension N-terminal to the CXXC motif compared with the shorter 30 −34 amino acids for DsbA members. In this respect, DsbA2 may be more similar to DsbC (107 amino acids to CXXC motif), but unlike DsbC, DsbA2 lacks a well defined dimerization domain. Other similarities with DsbC include a common amino acid residue adjacent to the conserved cis-proline (TPA) instead of VPA found in DsbA (Ren et al., 2009). The similarly to DsbC isomerases might explain the ability of the free thiol of C89S mutant protein to form complexes with substrates as demonstrated in Fig. 5D lane 2. However, the redox status of DsbA2 in the periplasm was more typical of DsbA than DsbC. If DsbA2 was DsbC-like, most of the protein would have existed in the reduced state. Our studies do not exclude the possibility that DsbA2 may be bifunctional or exist in different redox states as a monomer or potential dimer, all of which might vary with growth stage. We are currently investigating the nature of the substrates captured by DsbA2 C89S mutant protein that might support disulfide isomerase activity.

To our knowledge, all of the dsb genes studied to date are nonessential for viability, though it is not uncommon for Gram-negative bacteria to express several DsbA-like enzymes. For example, Neisseria meningitidis contains three DsbA-like homologues (Tinsley, et al., 2004), Salmonella enterica expresses SeDsbA, SeDsbL, and SeSgrA that have been crystallized and shown to be DsbA-like (Jarrott et al., 2010), and in uropathogenic E. coli a second DsbA/B like system, DsbI/L has been identified (Grimshaw, et al., 2008). In the case of N. meningitidis, single and double deletion mutants retained full virulence indicating considerable redundancy in function (Tinsley et al., 2004). It is noteworthy that the triple mutant, while viable, exhibited a temperature sensitive growth phenotype (Tinsley, et al., 2004). Several studies have shown that DsbA is required for assembling various extra-cytoplasmic virulence factors including components of T2 and T3 secretion systems and toxins (Heras et al., 2009). Our inability to isolate mutants of dsbA2 suggests that DsbA2 must provide an as yet undefined essential function(s) in L. pneumophila and possibly other bacteria expressing a dsbA2 orthologue.

In addition to L. pneumophila and C. burnetii, other human and plant pathogens expressing T4SS include: B. suis, Bartonella henslae, Ehrlichia sp., Anaplasma sp., R. prowazekii and Agrobacterium tumefactions (Llosa et al., 2009). All of these bacteria express an orthologue of DsbA2, suggesting a role in assembling components of the respective T4SS. Bacterial genera not containing T4SS, but expressing DsbA2 include: Caulobacter, Bradyrhizobium, Azospirillum, Paracoccus, Methylobacterium, and Magnetospirillum. Two notable exceptions in bacteria that express T4SS systems include B. pertussis (Ptl T4SS) which expresses DsbA1 and DsbC orthologues and H. pylori in which an orthologue of DsbA is absent. In the case of H. pylori, the acidic gastric mucosa, like anaerobic environments, do not favor stability of disulfide bonds. Further phylogenetic analyses of bacteria containing T4SS will likely confirm an evolutionary relationship with DsbA2. The phenotype of the P198T mutant suggests that the conserved cis-proline mutation first exploited in E. coli might be applied to other Gram-negative bacteria as a strategy to capture protein substrates associated with virulence or other cellular functions.

In addition to P198T capture of Dot/Icm components, a wide range of substrate proteins were captured (Table 2), including enhanced entry proteins (Enh) that are required for entry into amoeba (Liu et al., 2008). Perhaps the reduced attachment and invasion seen with P198T mutant protein might be due to impairment of Enh function (Fig. 6). Heat shock proteins HtpA and HtpB (GroES and GroEL), previously reported as periplasmic proteins, were captured in this study (Hoffman et al., 1990; Garduno et al., 1998a and 1998c) and it is noteworthy that the localization of HtpB onto the cell surface is Dot/Icm dependent (Garduno et al., 1998c). HtpB contains four cysteine residues (E. coli GroEL contains two) whose oxidation might be important for function and like DsbA2 is enriched in the hyper virulent cyst form. Ironically, HtpA contains no cysteine residues and raises the possibility of co-capture (with HtpB) of molecular complexes. It is noteworthy that other Dot/Icm proteins that contain no cysteine residues such as DotD, IcmW and IcmY were not captured, nor were cytoplasmic proteins rich in cysteine residues like isocitrate dehydrogenase. However, as noted previously (Kadokura et al., 2004), despite the addition of excess iodoacetamide to alkylate free thiols to limit capture of cytoplasmic proteins, some cytoplasmic proteins were captured by this procedure. In retrospect, one might limit cytoplasmic contamination by isolating captured complexes by osmotic shock, though these strategies could potentially limit capture of membrane associated complexes. While subunits of OmpS were also captured in these studies, it is unlikely that DsbA2 plays a major role in catalyzing disulfide bond cross-linking of the subunits as one might expect the over expression of the P198T mutant to have resulted in restricted in vitro growth or changes in the OmpS profile. However, further studies will be required to fully explore the role of DsbA2 in assembly of the OmpS oligomer.

The lack of motility and assembled flagella in the P198T over-expressing mutant described here mirrors what is known in other Gram-negative bacteria with DsbA mutations: ΔdsbA E. coli produce no T4 pili (BFP) (Vogt et al., 2010), and Salmonella lacking the DsbA deriviative SrgA produce no fimbriae (Bouwman et al., 2003). The absence of flagellin in the periplasmic shockate with P198T mutant protein suggests that DsbA2 either catalyzes a disulfide bond required for flagella biosynthesis or indirectly, as through a defect in FlgI assembly (flagella motor defect) triggers degradation of subunits and or activation of regulatory systems like CpxR that might repress the flagella system (Ravio, 2005).

In summary, our studies assign biological functions to a family of proteins previously annotated as 27-kDa outer membrane proteins similar to Com1 as disulfide bond oxidoreductases. The DsbA2 lineage is phylogenetically distinct from members of the DsbA family. Remarkably, all members of this group also lack orthologues of DsbC and DsbG, but retain the DsbD reductase, suggesting the possibility that DsbA2 might be bifunctional, providing disulfide-bond oxidizing as well as editing functions (protein disulfide isomerase) required for repairing nonconsecutive disulfide bonds. Finally, the DsbA2 lineage is conserved among those bacterial species that also express a T4SS, suggesting a likely role for DsbA2 in assembly or function of these macromolecular structures.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 strains 130b (also known as AA100, ATCC BAA-74) and dotA mutant (kind gift of Dr. Abu-Kwaik), and the Philadelphia-1 strain Lp02 and Lp03 (Berger and Isberg, 1993) were grown aerobically at 37°C on buffered charcoal yeast extract agar (BCYE) (Pasculle et al., 1980) or in buffered yeast extract (BYE) broth and supplemented with α-ketoglutaric acid (1 mg/ml), ferric pyrophosphate (250 µg/ml), L-cysteine (40 µg/ml), thymidine (100 µg/ml), and antibiotics where required. Starter cultures were prepared as previously described (LeBlanc et al., 2006) and used to inoculate pre-warmed BYE to an optical density at 620 nm (OD620) of 0.2. For growth curve determinations, samples were taken every two hours (triplicate) and optical density was determined at 620 nm. E. coli strain DH5α (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA) and BL21(DE3) CodonPlus™RIL (Stratagene) were grown at 37°C on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar or in LB broth supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics. Antibiotics (Sigma-Aldrich Ltd.) were added to media at the following concentrations, when appropriate: streptomycin (100 µg/ml), kanamycin (40 µg/ml), gentamicin (10 µg/ml), chloramphenicol (20 µg/ml), and ampicillin (100 µg/ml). All strains were stored at −85°C in nutrient broth containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide.

Phylogenetic analysis of DsbA1 and DsbA2

DsbA1 and DsbA2 amino acid sequences used in phylogenetic analysis were obtained from the Legiolist web-server (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/LegioList/genome.cgi) and orthologous genes from GenBank by BLASTP search using DsbA1 and DsbA2 of Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia-1. Phylogenetic trees were generated by multiple sequence alignment of unedited DsbA2 sequences using ClustalW. Protein prediction software Phyre (www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/~phyre) was used align DsbA2 onto the crystal structure of DsbA of E. coli.

Construction of Lp02ΔdsbA1 and Lp02ΔdsbA2

Allelic replacement was performed as described previously (Chalker et al., 2001;Hiltz et al., 2004). Briefly, 700 bp flanking regions of the dsbA gene were amplified with primers pairs DSBA1-1F and DSBA1-2R and DSBA1-3F and DSBA1-4R (see Table 1). The internal primers DSBA1-2R and DSBA1-3F were complementary to 5’ and 3’ regions of a gentamicin resistance cassette amplified from pPH1J1 (Hirsh and Beringer, 1984), so that the PCR products of the dsbA1 flanking regions would anneal to the gentamicin resistance cassette in a three way PCR. A final PCR reaction using outside primers DSBA1-1F and DSBA1-4R generated the linear DNA fragment that was electroporated into Lp02 as described previously (Hiltz et al., 2004) and plated on BCYE with thymidine and gentamicin. Colonies were screened by PCR for deletion of dsbA1 using both flanking primers and primers designed to internal sequences of dsbA1. Allelic replacement strategies to produce deletions of dsbA2 were essentially as described for dsbA1: primers DSBA2-1F, DSBA2-2R, DSBA2-3F, and DSBA2-4R were used to generate dsbA2 flanking regions and to incorporate a kanamycin resistance cassette between them. The final construct was electroporated into Lp02 and Lp03 (a dotA mutant strain kindly provided by Michelle Swanson). A second dsbA2 knockout strategy utilized native NsiI restriction sites in the middle of the dsbA2 gene to insert a kanamycin resistance cassette. The commercial vector pBlueScript SK+ (Stratagene) was restricted with BamHI and EcoRI, and a PCR product generated with DsbA21-F and DsbA24-R (containing the dsbA2 gene and flanking regions) was similarly restricted with BamHI and EcoRI and ligated to produce pBS:dsbA2. This vector was restricted with NsiI, blunted, and a blunted kanamycin cassette was inserted, effectively disrupting the dsbA2 coding sequence. PCR was performed to amplify the kanamycin disrupted dsbA2 and flanking regions and the linear DNA was electroporated into Lp02 and Lp03 as above. Both linear DNA constructs were also used for natural transformation of Lp02 and Lp03 and in the AA100 strains (130b) as described previously (Sexton and Vogel, 2004).

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| DsbA2 F: | GGGAATTCTAAGGGGAATTACGTGAAATTTAC |

| DsbA2 R: | TAA GGA TCC TTA ATTGCCAGCCGCC |

| C89S-F: | GGGAATTCTAAGGGGAATTACGTGAAATTTAC |

| C89S-R: | GATGCCATTTTTTTGGAATGAATGC |

| P198T-F: | CATTTGATGGGTACAACAGCCTTTATAATTGG |

| P198T-R: | CCA ATT ATA AAG GCT GTT GTA CCC ATC AAA TG |

| DsbA2 6his: | TAA GGA TCC TTA GTG ATG ATG ATG ATG ATG ATT GCC AGC CGC C |

| DsbA1-1F: | AGTACCGCCACCTAAGTCGACCTCAAGCTATAAAGGATATTC |

| DsbA1-2R: | AAACTCGAGCCCGATGTCGAGCCCTCTG |

| DsbA1-3F: | TCATGGATCCGCAAGGTATTAGTAC |

| DsbA1-4R: | ACAGGCTTATGTCAAGTCGACGTTGCCAAAGCAGTCATTGGC |

| DsbA2-1F: | AACGGATCCCTGAGGTACCCTGACTTG |

| DsbA2-2R: | GTGGCTTTGAGCTCGGTATTTTCAATGGTAGATGCCA |

| DsbA2-3F: | CTAAGAGCTCGGTACCCGGAGCAATCACTACGTGAG |

| DsbA2-4R: | GGCGGATCCGAGTAATACCACCTGAAATTG |

A suicide vector (pRDXA) developed previously (Morash, et al., 2009) was used to disrupt the dsbA2 coding sequence using the two constructs described above. This vector utilizes metronidazole as a counter-selectable marker to confirm loss of the plasmid and in conjunction with a positive-selection marker, in this case kanamycin, can be used to increase the likelihood of obtaining low frequency recombination events. Approximately 10 µg of plasmid DNA was electroporated into electrocompetent L. pneumophila Lp02, plated on BCYE medium supplemented with streptomycin, kanamycin, and thymidine, and incubated for 3 to 4 days. The resulting transformants were replica plated and screened for loss of metronidazole sensitivity on BCYE supplemented with 20 µg/ml of metronidazole (loss of the plasmid vector) and on chloramphenicol (12 µg/ml) as a second marker for the plasmid.

Construction of AA100ΔdsbA1

Natural competence was induced in L. pneumophila strain AA100 (130b) as described previously (Sexton and Vogel, 2004). Briefly, dime-sized patches were made on BCYE of AA100 from freshly grown plates. These patches were allowed to grow for 16 h at 25°C, and then 5 µg of genomic DNA from Lp02ΔdsbA1 was carefully dropped onto the surface of the patch. The patches were left to grow for 48–72 hours, and then resuspended in water and plated on BCYE containing gentamicin. Colonies were screened by PCR for deletion of dsbA1.

Construction of C89S and P198T-His6 mutants

To create mutant alleles of DsbA2, cysteine at position 89 was changed to serine using a PCR based strategy with primer pairs C89S-F and C89S-R and similarly for DsbA2P198T mutants, primer pairs P198T-F and P198-R were used. The PCR amplicons were restricted with EcoR1/BamHI and cloned into pMMB206 to enable expression under a controllable promoter ( lacIq and IPTG inducible promoter) (Morales et al., 1991). For the P198T construct, a His6 tag was also engineered by PCR. All constructs were confirmed by PCR, DNA sequencing and introduced into the Lp02 and AA100 strains by electroporation or by natural transformation.

DsbA2 antibody production

dsbA2 was amplified with primers DsbA2expNde1 and DsbA2expBamHI, digested with appropriate enzymes, and cloned into the pET15b expression system. An N-terminal His6-DsbA2 was over-expressed and purified by Ni ++ chromatography. Purified protein was used to generate polyclonal antibodies in mice as previously described (Helsel et al., 1987) and all western blotting was performed with DsbA2-specific antibody diluted 1:10,000 in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20. Immunoblots of whole cell lysates of Lp02 were used to confirm specificity of the antibody. DsbA2 antibody was monospecific for a 30 kDa protein with no cross-reactivity with DsbA1.

Cell fractionation

Subcellular localization of DsbA2 protein was conducted using L. pneumophila harvested from 50-ml cultures that were grown to stationary phase in BYE broth at 37°C. Bacterial cells were disrupted by sonication and lysates fractionated into soluble and membrane-associated proteins by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g (Butler et al., 1985; Vincent et al., 2006). Total membrane fractions were treated with 1% Triton X100 and the suspension subjected to ultracentrifugation to separate the soluble fraction (inner membrane and periplasmic proteins) from the outer membrane pellet. Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot using the following monospecific antisera: DsbA2, and OmpS (Butler et al., 1985), LepB (Vincent, et al., 2003) and IHF (Morash et al., 2009).

Electron microscopy and immunogold labeling

Bacteria were prepared for electron microscopy by embedding in TAAB resin and sectioned or directly to grids (whole cells) as previously described (Garduno et al., 2002). Immunogold labeling was carried out at room temperature as previously described (Fernandez et al., 1996). Antibodies used in these studies included rabbit OmpS-specific antibody (1/400) and mouse DsbA2-specific antibody (1/400 to 1/50 dilutions) and the secondary antibody (anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG) conjugated to 10-nm colloidal gold spheres [Sigma Immunochemicals]) was routinely diluted 1:100. After the labeling procedure, the specimens were fixed by floating the grids on drops of 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 min, repeatedly washed on drops of deionized water, and then stained with 2% (wt/vol) aqueous uranyl acetate. Statistical analysis on gold particle localization was performed using the method of Mallette (Mallette, 1969) as described previously (Garduno et al., 1998c).

Insulin assay

Reductase activity was assessed by an insulin precipitation assay (Bardwell et al., 1991) with minor modifications. Bovine insulin was dissolved in Tris/HCl to 10 mg/ml (1.67 mM), and titrated to pH 7.5, creating a clear solution. Reactions (triplicate) were carried out in 200 µl of 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.0, 150 µM insulin, 0.33 mM DTT, and 2 mM EDTA and incubated in 96 well plate format at room temperature, taking OD650 readings at time intervals noted. DsbA2, P198T mutant protein and a bovine serum albumin control were added to the assay in equimolar concentrations.

Competition assay

Purified DsbA2 and P198T mutant protein were added to a modified insulin precipitation reaction by first establishing a rate with DsbA2 and then adding equivalent and higher concentrations of the P198T mutant protein. Reactions were performed as described in the insulin assay, except the concentration of DTT was increased to 0.75 mM and the insulin decreased to 86 µM.

Periplasmic redox status of DsbA2 by AMS/gel-shift

The redox status of DsbA2 was determined by alkylation of free thiol groups by 4-acetamido-4’-maleimidylstilbene-2,2’-disulfonic acid (AMS Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) essentially as described (Kadokura et al., 2004). Briefly, L. pneumophila was grown to stationary phase (∼24 h) when DsbA2 is most abundant and whole cells were divided into aliquots, one of which was first treated with 10 mM DTT, then TCA precipitated, and alkylated with 100 mM AMS; one TCA precipitated, then alkylated with AMS; and one served as an untreated control. Each of the samples was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot. AMS shifts the mass by 490 Da leading to a band shift.

Acanthamoeba castellanii infection

A. castellanii (ATCC 30010) was maintained in ATCC medium 354 at 25°C. For infection, a 48-hr culture of A. castellanii was washed and resuspended in Tris-buffered salt solution containing 2 mM KCl, 1mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM Tris, with the pH adjusted to 6.8 to 7.2 (Berk et al., 1998). Approximately 105 A. castellanii per ml were infected with 103 CFU/ml of L. pneumophila from an overnight culture grown in the presence or absence of IPTG. All experiments were performed in triplicate at 30°C, and at each time point wells were scraped to remove adherent amoeba, and bacteria were enumerated via decimal dilution in sterile water and plating on BCYE agar plates as previously described (Morash et al., 2009). Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation.

HeLa cell infection

HeLa cells were grown in minimal essential medium (MEM) as described previously (Garduno et al., 1998b). HeLa cells were resuspended in MEM without antibiotics to a concentration of 106 cells/ml and left to adhere for 1 to 2 hrs. L. pneumophila was standardized to an OD600 of 1.0. One hundred microliters of the bacterial suspension was added to triplicate wells to a final inoculum 108 bacteria/ 106 HeLa cells. Plates were centrifuged at 500 rcf for 5 minutes at room temperature in a clinical centrifuge to maximize contact of bacteria with the HeLa cell monolayer and then incubated for 3 hrs to facilitate infection. For attachment assays, monolayers were washed six times with PBS, lysed with water and vigorous pipetting, and decimal dilutions were plated in triplicate on BCYE agar for bacterial enumeration. For invasion assays, monolayers were washed six times with PBS, treated for 1 hr with MEM containing 50 µg/ml gentamicin, washed six times with PBS, lysed and enumerated as detailed above.

Hemolysis assay

Human red blood cells (UVA Blood Bank) were diluted in PBS, washed by centrifugation until supernatant was colorless, and incubated with bacterial strains at an MOI of 50:1 in a final volume of ∼1 ml as generally described (Kirby et al., 1998). Legionella strains and RBCs were mixed, pelleted for 3 min at 10,000 g, and after 2 hours 100 µl aliquots of supernatants were transferred to microtitre plates, and absorbance measured at OD415 for hemoglobin release.

SDS-PAGE and diagonal gel electrophoresis of cellular extracts

Preparation of cellular extracts and diagonal gel electrophoresis were as described by Kadokura (Kadokura et al., 2004). Briefly, 4L of AA100 [strain with P198T] was induced at an OD600 of 1.0 with 1 mM IPTG for 15 hours. The cells were centrifuged and washed once with 1/10th volume ddiH20, then re-suspended in 1/10th volume cold ddiH2O. Dry TCA was added to ∼8%, the cells were lysed on ice for 20 minutes, centrifuged for 10 minutes, and the pellet washed twice with acetone and dried. The pellet was alkylated in 100 mM TrisHCl (pH 8.0) containing 0.5% SDS and 100 mM iodoacetamide. The alkylated lysate was then diluted four times with 50 mM TrisHCl (pH 8.0) containing 300 mM NaCl and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to pellet insoluble material. The cleared lysate was loaded onto 4 separate 1 ml Ni++ columns pre-equilibrated with buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS). The columns were washed with 8 column volumes of Buffer A containing 20 mM imidazole and protein fractions eluted with 5 column volumes of Buffer A + 250 mM imidazole. Fractions containing DsbA2 P151T – His6 were pooled and concentrated by spin column and centrifugation. Proteins were resolved on Invitrogen Nu-Page Bis/Tris 4–12% SDS-PAGE at 200 V for 45 minutes under non-reducing conditions. The lane was excised and incubated in warm 100 mM DTT for 15 minutes, then placed in Laemmli loading buffer without bromophenol blue + 100 mM iodoacetamide for 5 minutes. The excised lane was placed on top of another Invitrogen Nu-Page SDS Bis/Tris 4–12% gel that had been modified by removal of gel material separating lanes as previously described (Hoffman et al., 1992a). The gel slice was locked in place by addition of stacking gel, and electrophoresed at 200 V for 45 minutes, followed by silver staining.

Protein identification by mass spectrometry

Gel slices containing proteins of interest were transferred to siliconized tubes and prepared for mass spectrometry by standard procedures in the Biomolecular Core facility of the University of Virginia School of Medicine. Tryptic digests were analyzed by LC-MS on a Thermo Electron LTQFT mass spectrometer. The digest was analyzed using the double play capability of the instrument acquiring full scan mass spectra to determine peptide molecular weights and product ion spectra to determine amino acid sequence in sequential scans. The data were analyzed by database searching using the Sequest search algorithm against L. pneumophila. MALDI ToF MS was also used to identify proteins in some experiments and also performed by the Biomolecular Core facility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank J. Beckwith and J. Vogel for helpful comments and suggestions and to I. Olekhnovich for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant R01 AI066058 to PSH and NIH training grant T32 AI07046 to MJL.

References

- Albert-Weissenberger C, Sahr T, Sismeiro O, Hacker J, Heuner K, Buchrieser C. Control of flagellar gene regulation in Legionella pneumophila and its relation to growth phase. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:446–455. doi: 10.1128/JB.00610-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell JC, McGovern K, Beckwith J. Identification of a protein required for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Cell. 1991;67:581–589. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger KH, Isberg RR. Two distinct defects in intracellular growth complemented by a single genetic locus in Legionella pneumophila. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:7–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk SG, Faulkner G, Garduno E, Joy MC, Ortiz-Jimenez MA, Garduno RA. Packaging of live Legionella pneumophila into pellets expelled by Tetrahymena spp. does not require bacterial replication and depends on a Dot/Icm-mediated survival mechanism. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:2187–2199. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01214-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk SG, Ting RS, Turner GW, Ashburn RJ. Production of respirable vesicles containing live Legionella pneumophila cells by two Acanthamoeba spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:279–286. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.279-286.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwman CW, Kohli M, Killoran A, Touchie GA, Kadner RJ, Martin NL. Characterization of SrgA, a Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium virulence plasmid-encoded paralogue of the disulfide oxidoreductase DsbA, essential for biogenesis of plasmid-encoded fimbriae. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:991–1000. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.3.991-1000.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand BC, Sadosky AB, Shuman HA. The Legionella pneumophila icm locus: A set of genes required for intracellular multiplication in human macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:797–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brassinga AK, Hiltz MF, Sisson GR, Morash MG, Hill N, Garduno E, Edelstein PH, Garduno RA, Hoffman PS. A 65-kilobase pathogenicity island is unique to Philadelphia-1 strains of Legionella pneumophila. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:4630–4637. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.15.4630-4637.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brassinga AKC, Kinchen JM, Cupp ME, Day SR, Hoffman PS, Sifri CD. Caenorhabditis is a metazoan host for Legionella. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:343–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01398.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler CA, Hoffman PS. Characterization of a major 31-kilodalton peptidoglycan-bound protein of Legionella pneumophila. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2401–2407. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2401-2407.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler CA, Street ED, Hatch TP, Hoffman PS. Disulfide-bonded outer membrane proteins in the genus Legionella. Infect Immun. 1985;48:14–18. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.1.14-18.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B, Swanson MS. Expression of Legionella pneumophila virulence traits in response to growth conditions. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3029–3034. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3029-3034.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalker AF, Minehart HW, Hughes NJ, Koretke KK, Lonetto MA, Brinkman KK, Warren PV, Lupas A, Stanhope MJ, Brown JR, Hoffman PS. Systematic identification of selective essential genes in Helicobacter pylori by genome prioritization and allelic replacement mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1259–1268. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1259-1268.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier X, Gabay JE, Reyes M, Zhu JW, Weiss A, Shuman HA. Chemical genetics reveals bacterial and host cell functions critical for type IV effector translocation by Legionella pneumophila. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(7):e1000501. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie PJ, Atmakuri K, Krishnamoorthy V, Jakubowsk iS, Cascales E. Biogenesis, architecture, and function of bacterial type IV secretion systems. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:451–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conover GM, Derre I, Vogel JP, Isberg RR. The Legionella pneumophila LidA protein: A translocated substrate of the Dot/Icm system associated with maintenance of bacterial integrity. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:305–321. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey FE, Berg HC. Mutants in disulfide bond formation that disrupt flagellar assembly in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1043–1047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AJ, Diaz DA, Mecsas J. A dominant-negative needle mutant blocks type III secretion of early but not late substrates in Yersinia. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76:236–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depuydt M, Leonard SE, Vertommen D, Denoncin K, Morsomme P, Wahni K, Messens J, Carrol KS, Collet J-F. A periplasdmic reducing system protects single cysteine residues from oxidation. Science. 2009;326:1109–1111. doi: 10.1126/science.1179557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner G, Garduno RA. Ultrastructural analysis of differentiation in Legionella pneumophila. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:7025–7041. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.24.7025-7041.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner G, Berk SG, Garduno E, Ortiz-Jimenez MA, Garduno RA. Passage through Tetrahymena tropicalis triggers a rapid morphological differentiation in Legionella pneumophila. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:7728–7738. doi: 10.1128/JB.00751-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez R, Logan S, Lee S, Hoffman P. Elevated levels of Legionella pneumophila stress protein Hsp60 early in infection of human monocytes and L929 cells correlate with virulence. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1968–1976. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.1968-1976.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields BS. The molecular ecology of Legionellae. Trends in Microbiology. 1996;4:286–290. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliermans CB, Cherry WB, Orrison LH, Smith SJ, Tison DL, Pope DH. Ecological distribution of Legionella pneumophila. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;41:9–16. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.1.9-16.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco IS, Shuman HA, Charpentier X. The perplexing functions and surprising origins of Legionella pneumophila type IV secretion effectors. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:1435–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garduno RA, Garduno E, Hoffman PS. Surface-associated Hsp60 chaperonin of Legionella pneumophila mediates invasion in a HeLa cell model. Infect Immun. 1998a;66:4602–4610. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4602-4610.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garduno RA, Quinn FD, Hoffman PS. HeLa cells as a model to study the invasiveness and biology of Legionella pneumophila. Can J Microbiol. 1998b;44:430–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garduno RA, Garduno E, Hiltz M, Hoffman PS. Intracellular growth of Legionella pneumophila gives rise to a differentiated form dissimilar to stationary-phase forms. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6273–6283. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6273-6283.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garduno RA, Faulkner G, Trevors MA, Vats N, Hoffman PS. Immunolocalization of Hsp60 in Legionella pneumophila. J Bacteriol. 1998c;180:505–513. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.505-513.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw JPA, Stirnimann CU, Brozzo MS, Malojcic G, Grutter MG, Capitani G, Glockshuber R. DsbL and DsbI form a specific dithiol oxidase system for periplasmic arylsulfate sulfotransferase in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2008;380:667–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix LR, Mallavia LP, Samuel JE. Cloning and sequencing of Coxiella burnetii outer membrane protein gene com1. Infect Immun. 1993;61:470–477. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.470-477.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heras B, Shouldice SR, Totsika M, Scanlon MJ, Schembri MA, Martin JL. DSB proteins and bacterial pathogenicity. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:215–225. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsel LO, Bibb WF, Butler CA, Hoffman PS, McKinney R. Recognition of a genus-wide antigen of Legionella by a monoclonal antibody. Current Microbiology. 1987;16:201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Hiltz MF, Sisson GR, Brassinga AKC, Garduno E, Garduno RA, Hoffman PS. Expression of magA in Legionella pneumophila philadelphia-1 is developmentally regulated and a marker of formation of mature intracellular forms. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3038–3045. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.10.3038-3045.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch PR, Beringer JE. A physical map of pPH1JI and pJB4JI. Plasmid. 1984;12:139–141. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman PS, Seyer JH, Butler CA. Molecular characterization of the 28- and 31-kilodalton subunits of the Legionella pneumophila major outer membrane protein. J Bacteriol. 1992a;174:908–913. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.908-913.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman PS, Houston L, Butler CA. Legionella pneumophila htpAB heat shock operon: Nucleotide sequence and expression of the 60-kilodalton antigen in L. pneumophila-infected HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3380–3387. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3380-3387.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman PS, Ripley M, Weeratna R. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of a gene (ompS) encoding the major outer membrane protein of Legionella pneumophila. J Bacteriol. 1992b;174:914–920. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.914-920.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren A. Thioredoxin catalyzes the reduction of insulin disulfides by dithiothreitol and dihydrolipoamide. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:9627–9632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrott R, Shouldice SR, Guncar G, Totsika M, Schembri MA, Heras B. Expression and crystallization of SeDsbA, SeDsbL and SeSrgA from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2010;66:601–604. doi: 10.1107/S1744309110011942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadokura H, Beckwith J. Mechanisms of oxidative protein folding in the bacterial cell envelope. Antiox. Redox Signal. 2010;13:1231–1246. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]