Abstract

Background

Bivalirudin, a direct thrombin inhibitor, is a widely used adjunctive therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous intervention (PCI). Thrombin is a highly potent agonist of platelets and activates the protease-activated receptors, PAR1 and PAR4, but it is not known whether bivalirudin exerts anti-platelet effects in PCI patients. We tested the hypothesis that bivalirudin acts as an anti-platelet agent in PCI patients by preventing activation of PARs on the platelet surface.

Methods and Results

The effect of bivalirudin on platelet function and systemic thrombin levels was assessed in patients undergoing elective PCI. Mean plasma levels of bivalirudin were 2.7 ± 0.5 μM during PCI which correlated with marked inhibition of thrombin-induced platelet aggregation and significantly inhibited cleavage of PAR1. Unexpectedly, bivalirudin also significantly inhibited collagen-platelet aggregation during PCI. Collagen induced a conversion of the platelet surface to a procoagulant state in a thrombin-dependent manner which was blocked by bivalirudin. Consistent with this result, bivalirudin reduced systemic thrombin levels by more than 50% during PCI. Termination of the bivalirudin infusion resulted in rapid clearance of the drug with a half-life of 29.3 minutes.

Conclusions

Bivalirudin effectively suppresses thrombin-dependent platelet activation via inhibition of PAR1 cleavage and inhibits collagen-induced platelet procoagulant activity as well as systemic thrombin levels in patients undergoing PCI.

Keywords: thrombin, PAR1, PAR4, collagen, platelets, arterial thrombosis

Most treatment strategies for acute coronary syndromes or adjunctive therapy for PCI are aimed at inhibiting thrombin and platelet activity. The synthetic, direct thrombin inhibitor, bivalirudin (Angiomax), is approved for use as an anti-thrombotic agent in patients undergoing PCI. Bivalirudin binds reversibly to thrombin at both its active site and exosite I,1 and inhibits both circulating and thrombus-bound thrombin.2 The safety and efficacy of bivalirudin in patients undergoing PCI has been assessed in patients with stable angina, unstable coronary syndromes, and acute ST elevation myocardial infarction. In general, these trials3-5 have documented that bivalirudin therapy during PCI is associated with non-inferior ischemic endpoints with significant reductions in the rates of major hemorrhage in comparison to heparin plus a GPIIb/IIIa inhibitor. However, the efficacy of adjunctive therapy as judged by the occurrence of ischemic complications during and after PCI, is strongly influenced by platelet function.6 Therefore, the clinical trial data indicate that bivalirudin might provide significant antiplatelet in addition to anticoagulant effects during PCI.

Thrombin, a primary mediator of platelet activation and aggregation through the PAR1 and PAR4 thrombin receptors,7, 8 has been shown to be elevated as a consequence of PCI wherein local thrombin activity in the culprit artery is greatly increased.9, 10 Whether bivalirudin affects PAR-dependent platelet function and ongoing thrombin generation in patients undergoing PCI is not clear.11-13 Moreover, the association between the currently used dosage of bivalirudin and suppression of platelet aggregation by the two major agonists thrombin and collagen has not been determined in patients undergoing PCI.

In the present study, we assessed the degree of protection from thrombin-induced platelet activation conferred by the clinically utilized dosages of bivalirudin in patients undergoing PCI. We also studied the effect of bivalirudin on systemic thrombin-antithrombin III levels and its effect on collagen-induced platelet aggregation and platelet pro-coagulant activity. For the first time, the plasma levels and half-life of bivalirudin was quantified at doses currently used during PCI. The data presented here support the concept that bivalirudin is not solely an anti-coagulant, but also attenuates platelet activation via inhibition of platelet thrombin receptors and collagen-dependent thrombin generation.

Methods

Patient Population

This mechanistic study examined the anti-platelet effects of bivalirudin, an approved adjunctive agent for PCI employing its commonly-used dose in the approved patient population for this drug. Outpatients with angina referred for coronary angiography, or PCI who had not received clopidogrel within 2 weeks were enrolled in the Tufts Medical Center Adult Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory. The population studied was relatively low-risk with patient characteristics summarized in Table 1. Inclusion criteria included men and non pregnant women, age 18 years or older referred for possible PCI who were eligible for bivalirudin therapy. All patients provided written informed consent before the initiation of the study. The study protocol was approved by the Tufts Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Exclusion criteria included current therapy with heparins or GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors, serum creatinine level >2.0 mg/dl, known hypersensitivity to bivalirudin, clopidogrel or aspirin, thrombocytopenia (platelet count <50,000/μL), severe systemic hypertension defined as systolic blood pressure >180 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure >110 mm Hg, acute pericarditis, active internal bleeding, history of bleeding diathesis within prior thirty days, history of intracranial hemorrhage, arteriovenous malformations or aneurysms, ischemic stroke within last thirty days, major surgical procedures or severe physical trauma within last thirty days, symptoms or findings suggestive of aortic dissection, pregnancy and participation in other clinical research studies within 30 days of enrollment. Eligible patients received the same weight-adjusted dosage of bivalirudin administered intravenously as a 0.75 mg/kg bolus followed by continuous infusion of 1.75 mg /kg/hr during the procedure. All patients were chronic aspirin (ASA) users and received ASA prior to the intervention. Oral clopidogrel (600 mg) was administered at the completion of PCI to patients who received coronary stents; these patients were subsequently discharged with a prescription of 75 mg clopidogrel daily.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Procedural Outcomes

| Patients (n) | 22 |

| Age | 63 ± 11 |

| Gender | 17 males / 5 females |

| Weight (kg) | 92 ± 23 |

| History of | |

| Hypertension | 68% |

| Dislipidemia | 77% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18% |

| Congestive heart failure | 0% |

| Average TIMI risk score | 2.2 ± 1.2 |

| Patients with pre-procedure ST segment depression | 5% |

| Patients with elevated baseline Troponin-I and/or CK-MB | 9% |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.96 ± 0.19 |

| Platelets (k/μl) | 223 ± 39 |

| Patients receiving coronary stents | 86% |

| Urgent reocclusion | None |

| Post PCI myocardial infarction | None |

| Death | None |

| Minor or major hemorrhage | None |

Data are reported as Mean ± SD.

Platelet Aggregation Studies in Patients

Venous blood samples were collected from PCI patients at baseline and at 30 min after initiation of bivalirudin infusion, using a 18-gauge needle and a 20 ml syringe prefilled with 2-mL of 4% sodium citrate. Whole blood was transferred into 15 ml polypropylene tubes with EDTA added for a final concentration of 0.25 mM. To prevent loss or dilution of bivalirudin from the patient samples, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) rather than washed platelets was used in all the aggregation experiments. PRP was harvested by centrifuging blood at 700g for 20 min at 30 °C. To prevent fibrin formation upon addition of thrombin agonist, the peptide glycine-L-prolyl-L-arginyl-L-proline (GPRP) (Sigma) was added (1 mM final concentration) to the PRP before performing platelet aggregation. Platelet aggregation was induced by 3 nM-1 μM thrombin (Haematologic Technologies), 5 μg/ml fibrillar type I collagen (Chronolog), 5 μM SFLLRN or 160 μM AYPGKF (synthesized with C-terminal amides at the Tufts Peptide Core Facility). Platelet aggregation was measured with a Chronolog 560VS/490-2D aggregometer with PPP (platelet poor plasma) serving as blank. Samples were recalcified with CaCl2 (2.5 mM final concentration) prior to addition of agonists. All reactions were conducted in final volumes of 250 μl at 37 °C while stirring at 900 rpm.

Quantification of Bivalirudin Concentration in Plasma

Bivalirudin levels in plasma were obtained from PCI patients just prior to bivalirudin infusion (baseline), immediately following bolus infusion, 30 minutes following the institution of the continuous infusion or at the end of PCI if the procedure was completed earlier (30 min), 5 min after termination of infusion (5 min POST), 15 min after termination of infusion (15 min POST), and 2 h after termination of infusion (2 h POST). Whole blood was drawn into 6 ml EDTA-containing test tubes and immediately transferred to ice. Platelet-poor plasma (PPP) samples were stored at -80 °C. PPP samples were shipped on dry ice to Frontage Laboratories (Malvern, PA) for determination of plasma drug levels using a Q-Trap 5000 MS/MS system equipped with an HPLC. The threshold level of detection of bivalirudin in plasma was 0.23 μM by the LC/MS/MS method.

Platelet Aggregation of Blood Samples from Normal Volunteers

Blood was obtained from adult healthy volunteers (n=10, 5 males, 5 females) from the greater Boston area recruited by Tufts IRB-approved procedures. PRP was obtained from the healthy volunteers in an identical manner as the PCI patients. To obtain the standard bivalirudin inhibition curves, various concentrations of (0.1-10μM) bivalirudin were preincubated with PRP for 2 min prior to addition of thrombin. Platelet aggregation assay was performed in an identical manner as with the PRP from patients. Thrombin EC 50 values were plotted as a function of bivalirudin concentration. To measure the effects of the presence of plasma proteins on collagen and thrombin-induced aggregation, gel-filtered platelets were further prepared from healthy volunteer PRP using Sepharose 2B columns in modified PIPES buffer as previously described.14 Platelet aggregation was measured using PIPES buffer as control. Inhibitors were added 2 min prior to addition of collagen or thrombin agonists.

Prothrombinase, TAT and TXB2 Assays

Thrombin generation was quantified in citrate-anticoagulated human PRP as described15 with simple modifications. Briefly, 250 μl of PRP from healthy donors was recalcified with CaCl2 (final 2.5 mM) and stimulated with 5 μg/ml collagen for 5 min at 37 °C while stirring at 200 rpm. Bivalirudin was added 3 min prior to collagen. Thrombin generation was quenched by addition of 20 mM EDTA in Hepes buffer, pH 7.5, on ice. Thrombin activity was measured using the chromogenic substrate S2238 as described.16 Quantification of thrombin-antithrombin III complexes (TAT) and TXB2 in the plasma from PCI patients obtained at baseline, 30 min after PCI, and 120 minutes after termination of bivalirudin infusion was performed by ELISA using commercially available kits (Affinity Biologicals, Cayman Chemicals, respectively) and following the manufacturer’s protocols. TAT and TXB2 ELISAs used 20 μL of plasma and 80 μL of buffer per assay well.

Annexin V and Span-12 Binding

Whole blood from healthy donors was diluted 1:10 in modified HEPES-Tyrodes buffer (10 mM Hepes, 137 mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 12 mM NaHCO3, 0.4 mM Na2PO4, 5.5 mM glucose and 0.35% BSA, pH 7.4). GPRP at a final concentration of 1 mM was added to prevent fibrin polymerization before addition of agonists. Diluted whole blood was incubated for 10 min with bivalirudin or PIPES buffer and then incubated for an additional 10 min with 5 μg/ml collagen, 20-50 nM thrombin or both at 37 °C. The samples were labeled with CD41a–PE antibody alone or with a mixture of CD41a–PE antibody and annexin V-FITC (BD Biosciences) in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Paraformaldehyde 1% was used to fix the platelets. Analysis was performed on a BD FACSCanto II Flow Cytometry System. Platelets were gated against the CD41a-PE-Ab channel and their characteristic log orthogonal and forward light scatter used to eliminate non-platelet derived events and debris. For Span-12 antibody binding, PRP anti-coagulated with citrate plus 1 mM GPRP was obtained from PCI patients at baseline or after 30 min PCI, or from normal volunteers. PRP was treated with 20 nmol/L thrombin at 37 °C for 15 min. Samples were then labeled with 1:1000 PAR1 antibody, Span 12-PE (which recognizes only intact PAR1), at room temperature for 30 min and then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and assessed by FACS as above.

Data Analysis

We quantified the degree of platelet inhibition conferred by bivalirudin during PCI using thrombin, AYPGKF, SFLLRN and collagen as agonists. From our previous bivalirudin spiking study8 with normal subjects using a standard deviation (SD) of 10%, and choosing a power of 95% and with an alpha = 0.05, we calculated that we would require at least 9 subjects in order to obtain a significant result if the true differences between baseline and the bivalirudin treatment groups were as small as 20%. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism5.0a using a paired two-tailed Student’s t-test. Pairwise comparisons of aggregometry results for each agonist were made between baseline (prior to receiving bivalirudin) and at the 30 min time point.

Results

Bivalirudin Efficiently Inhibits Thrombin-Induced Aggregation in Platelets from Patients Undergoing PCI

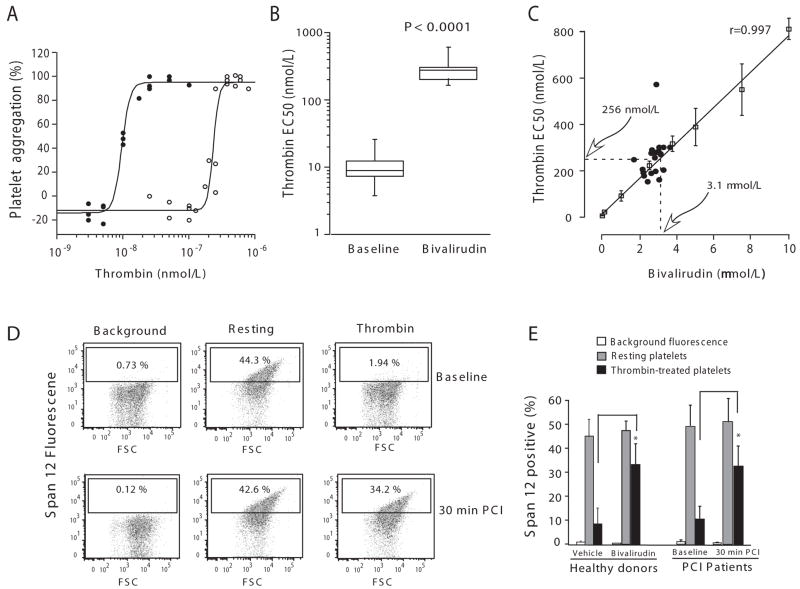

The demographic, clinical and procedural characteristics of the 22 patients comprising the study population are listed in Table 1. Although this mechanistic study was neither designed nor powered to assess clinical outcomes, no patient experienced an ischemic endpoint or suffered major or minor bleeding according to Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction criteria.17 We first assessed the effects of bivalirudin on thrombin, SFLLRN and AYPGKF-induced aggregation in platelet-rich plasma from the patients undergoing PCI. Thrombin is a potent agonist of both the PAR1 and PAR4 thrombin receptors, SFLLRN specifically activates PAR1, and AYPGKF specifically activates PAR4.8, 18, 19 Bivalirudin completely blocked platelet aggregation in response to high concentrations of exogenously added thrombin at the 30 min time point during the PCI procedure in all patients (Table 2). We next determined the concentration of thrombin that would overcome the inhibitory effects of the infused bivalirudin on platelets from each patient. Bivalirudin markedly right-shifted the thrombin aggregation curves by 26-fold to a mean thrombin EC50 of 256 ± 87 nM in the patients undergoing PCI (Figure 1A-C). However, the bivalirudin infusion had no significant effect on mean platelet aggregation in response to the synthetic peptide agonists SFLLRN or AYPGKF in the patients as compared to baseline (Table 2).

Table 2.

Inhibitory Effects of Bivalirudin on Platelet Aggregation and Systemic TAT levels in PCI Patients (n=22)a

| Baseline | 30 min | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombin (%) | 94 ± 8 | -10 ± 7 | < 0.0001 |

| SFLLRN (%) | 94 ± 8 | 90 ± 8 | 0.06 |

| AYPGKF (%) | 93 ± 9 | 90 ± 9 | 0.2 |

| Collagen (%)b | 61 ± 24 | 50 ±19 | <0.001 |

| TAT (pmol/L) | 215 ± 104 | 98 ± 41 | < 0.0001 |

| TXB2 (pg/mL) | 210 ± 30 | 230 ± 28 | 0.2 |

Platelets in PRP were isolated from PCI patients at baseline and after 30 min of bivalirudin infusion, and were stimulated with 50 nmol/L thrombin, 5 μmol/L SFLLRN, 160 μmol/L AYPGKF, and 5 μg/mL collagen. Platelet aggregometry was performed at 37 °C in the presence of 1 mM GPRP. TAT and TXB2 levels in plasma were analyzed by ELISA as described in the methods. Data are reported as Mean ± SD and P values were determined by paired t-tests.

Collagen-dependent aggregation was measured with 18 of the 22 PCI patients as shown in Fig 4A for individual patients.

Figure 1.

Bivalirudin protects PCI patients against thrombin-induced platelet aggregation and PAR1 cleavage. (A) Platelets in PRP were isolated from PCI patients at baseline (●) and after 30 min of bivalirudin infusion (○), and were stimulated with various concentrations of thrombin. Platelet aggregometry was performed at 37 °C in the presence of 1 mM GPRP. Aggregation data from three representative patients are plotted as a function of thrombin concentration. (B) The EC50 values of thrombin aggregation for all 22 PCI patients are reported as the median within the first and third quartiles (box). (C) The EC50 of thrombin-dependent aggregation for each patient sample at 30 min (●) was plotted as a function of plasma bivalirudin concentration. Overlayed on these patient data are the thrombin EC50 values (mean ± SD) of PRP from normal individuals (□) plotted as a function of spiked bivalirudin concentration. The solid line represents the least-squares fit of the data and the dashed lines are the mean thrombin EC50 (256 nmol/L) of the PCI patient population and predicted mean bivalirudin concentration (3.1 μmol/L) based on the inhibitory data from the normal individuals. (D-E) Platelets in PRP was isolated from patients (n=5) at baseline or 30 min PCI, or from healthy donors (n=3) and challenged with 20 nmol/L thrombin. Bivalirudin (2.7 μM) was spiked into the healthy donor PRP. Surface expression of the intact thrombin cleavage epitope of PAR1 on the platelet surface was then assessed by FACS. FACS results are shown for one representative PCI patient in D and the mean ± SE are shown in E for all the PCI patients and healthy donors, *P<0.015 by paired-sample t test.

PAR1 is the high affinity thrombin receptor on platelets and its activation is highly dependent on interactions between thrombin exosite I and the hirudin-like domain on the PAR1 extracellular domain.7 As bivalirudin also binds with high affinity to exosite I of thrombin, we postulated that bivalirudin might inhibit thrombin cleavage of PAR1 on the surface of platelets. The Span12 antibody, which binds only to uncleaved PAR1, was used to quantify thrombin cleavage of PAR1 on the platelet surface. We found that 20 nM thrombin caused 81% loss of Span12 binding to the platelet surface at baseline which was significantly protected by the 30 min bivalirudin infusion (Figure 1D-E). Similar protection against thrombin cleavage of PAR1 was observed by adding exogenous bivalirudin to platelets from healthy volunteers (Figure 1E).

Pharmacokinetics of Bivalirudin in Patients Undergoing PCI

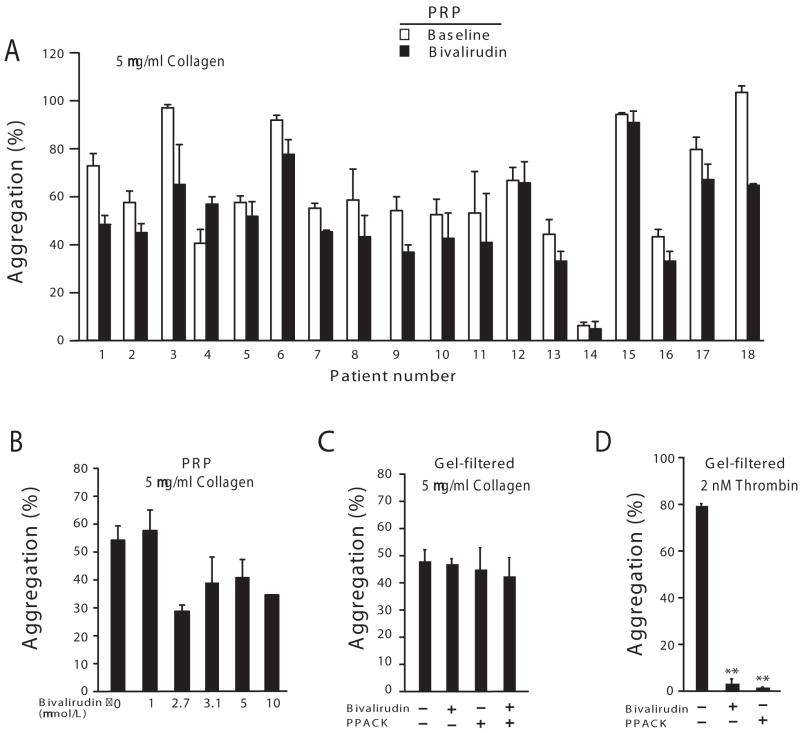

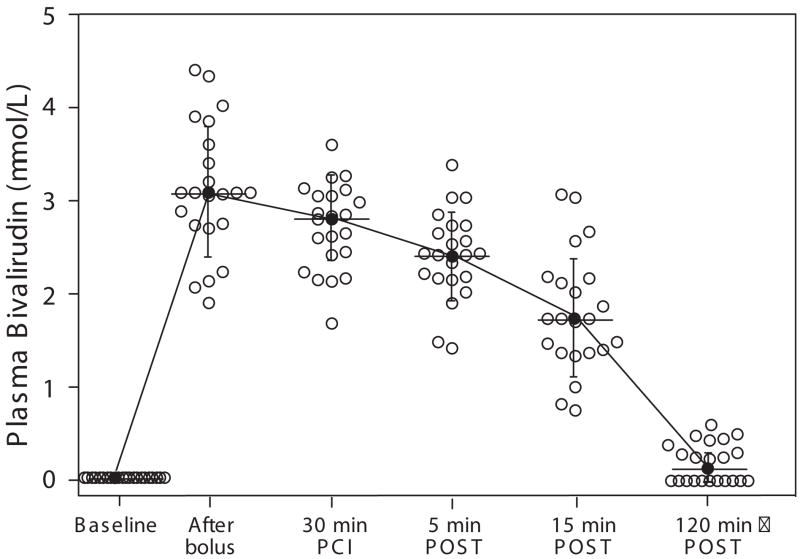

A previous pharmacokinetic study in PCI patients20 using the first FDA-approved dosage regimen of bivalirudin based on the Bivalirudin Angioplasty Trial (bolus of 1.0 mg/kg followed by an infusion of 2.5 mg/kg/h),21 yielded mean steady-state bivalirudin plasma levels of 5.6 μM (12.3 ± 1.7 μg/mL) and a terminal half-life of 25 min. However, the plasma levels and half-life of bivalirudin have not been determined using the current FDA approved dosage regimen of bivalirudin established by the REPLACE-2 study3 which employs a substantially reduced bivalirudin exposure (0.75 mg/kg bolus and 1.75 mg/kg/h infusion) for the duration of the PCI procedure. Therefore, we measured circulating bivalirudin drug levels from 22 PCI patients both during and after termination of bivalirudin infusion. Peak drug levels reached 3.2 ± 0.7 μM at the 5-10 min time point just after the bolus injection (Figure 2, Supplementary Table). The mean steady-state bivalirudin concentration during PCI was 2.7 ± 0.5 μM, a more than 50% reduction in the bivalirudin levels relative to patients that received the original 1.0 mg/kg bolus and 2.5 mg/kg/h infusion dosage.22 The distribution of steady-state drug levels in individual patients ranged from a low of 1.7 μM to a high of 3.7 μM. Despite these individual differences, all patients had dramatic right-shifts in their thrombin EC50 curves from a low of 150 nM to a high of 570 nM (Figure 1C). The thrombin-platelet aggregometry dose-response curve determined for a range of bivalirudin concentrations in whole blood gave a predicted mean plasma bivalirudin level of 3.1 μM which deviated by only 13% from the actual measured mean steady-state value of 2.7 μM in the patient samples (Figure 1C).

Figure 2.

Pharmacokinetics of the 0.75 mg/ml bolus plus 1.75 mg/kg/min infusion bivalirudin dosage in individual patients during and after PCI. Plasma bivalirudin levels were measured by LC/MS/MS for all 22 patients at six sequential time points: baseline, 5 min after bolus, 30 min after infusion, and 5 min, 15 min and 2 h after termination of infusion. The mean (●) ± SD are shown.

After discontinuation of the infusion, bivalirudin was rapidly cleared from the plasma with a mean half-life of 29.3 ± 15.3 min (Supplementary Table). Two hours after discontinuation of the bivalirudin infusion, residual plasma drug levels (0.2 μM) were only 11% of the steady-state levels.

Bivalirudin Significantly Decreases Systemic TAT Levels in Patients Undergoing PCI

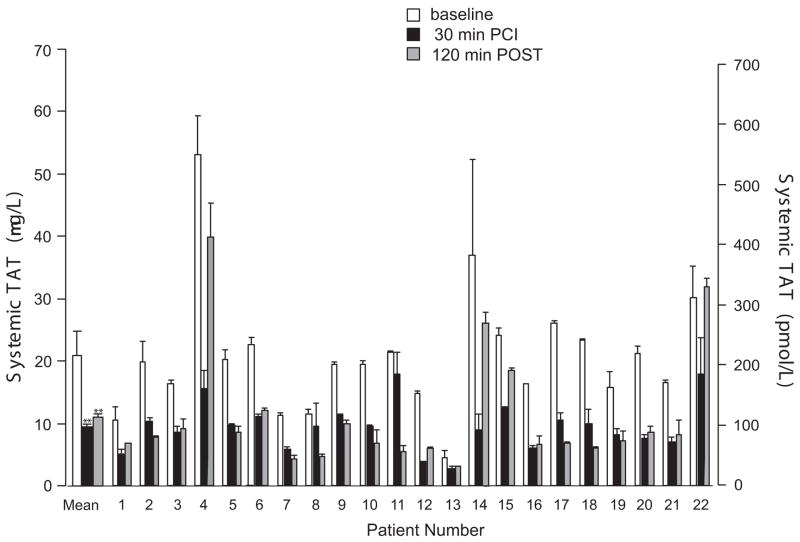

ACS patients have high systemic levels of various hemostatic markers that indicate an active prothrombotic and procoagulant state which can contribute to arterial thrombosis.9, 10 The observation that bivalirudin decreases platelet activity leads to the prediction that systemic thrombin levels may be decreased from baseline following infusion of bivalirudin in the patients undergoing PCI. Thrombin-antithrombin III (TAT) complexes are rapidly formed when antithrombin III irreversibly binds to active thrombin, thus circulating TAT complexes are a measure of systemic thrombin levels. Indeed, we found that the baseline mean systemic levels of TAT were 215 ± 104 pmol/L (normal range is 10-30 pmol/L) in our PCI patients. Given that TAT complexes have a very short plasma half-life of 15 min, these highly elevated TAT levels suggest ongoing systemic thrombin generation.9, 10 In order to assess the effect of bivalirudin on systemic thrombin, we compared plasma TAT levels at baseline, after 30 min of bivalirudin infusion, and 2 h after cessation of bivalirudin. As shown in Figure 3, the PCI patients had a significant drop in mean systemic TAT levels to 98 ± 41 pmol/L (Table 2), 30 min after initation of the bivalirudin infusion. Notably, there was no significant rebound in mean systemic TAT levels two hours (mean of 107 ± 92 pmol/L) after termination of the bivalirudin infusion (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Bivalirudin attenuates plasma TAT levels during and after PCI. Median plasma levels of thrombin-antithrombin complexes (TAT) were assessed by ELISA for samples collected at baseline, after 30 min of bivalrudin infusion, and 2 h POST-termination of the infusion. ELISAs were performed 3 separate times in duplicate or triplicate wells and the mean ± SD are shown, ** P < 0.0001 by paired-sample t test.

Bivalirudin Inhibits Collagen-Induced Platelet Activation

Unexpectedly, bivalirudin caused a statistically significant inhibition of collagen-induced aggregation of platelet-rich plasma obtained from the PCI patients at the 30 min time point as compared to baseline (Table 2, Figure 4A). The inhibitory effect of spiked bivalirudin on collagen-induced aggregation in platelet-rich plasma (Figure 4B) was not observed when plasma proteins were removed from the platelet preparations by gel-filtration (Figure 4C), consistent with previous data.23 Addition of exogenous thrombin to plasma-depleted platelets gave 80% platelet aggregation which was completely blocked by bivalirudin or the direct thrombin inhibitor, PPACK (Figure 4D). To rule out that the observed differences in collagen aggregation were due to variable inhibition of thromboxane pathways, we confirmed that plasma TXB2 levels24 were unchanged from baseline versus the 30 min time-point in the PCI patients (Table 2). This was expected, as the patients were documented long-term aspirin users with 20 of the 22 patients receiving their last ASA dose 4 h prior to the procedure and 2 patients receiving their last ASA dose just prior to the procedure.

Figure 4.

Bivalirudin suppresses collagen-induced platelet aggregation and procoagulant activity. (A) Platelets in PRP from the PCI patients at baseline and after 30 min of bivalirudin infusion, were stimulated with 5 μg/ml collagen and aggregometry performed. (B) The indicated concentrations (μmol/L) of bivalirudin were spiked into patient PRP (n=3) isolated at baseline and aggregation in response to 5 μg/ml collagen assessed. Identical results were seen with PRP from normal individuals (data not shown). (C-D) Gel-filtered platelets (normal volunteers, n=3) were preincubated for 2 min with bivalirudin (5 μmol/L) and/or PPACK (100 μmol/L) and then challenged with 5 μg/ml collagen or 2 nmol/L thrombin as indicated. **P<0.001 by paired-sample t test with Bonferroni correction.

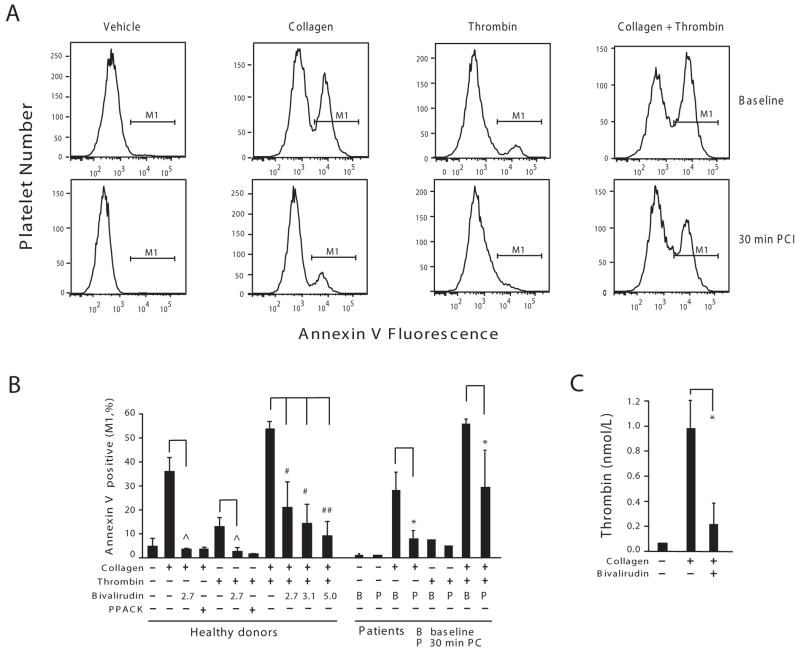

Bivalirudin Inhibits Collagen-dependent Platelet Procoagulant Activity

Given that inhibition of collagen-induced platelet aggregation by bivalirudin required the presence of plasma proteins (e.g. prothrombin and other coagulation factors), we tested the hypothesis that bivalirudin inhibits collagen-initiated aggregation by suppressing platelet-dependent thrombin generation. We used annexin V binding to assess the appearance of negatively charged phospholipids in individual platelets from PCI patients and healthy donors as a marker of procoagulant activity within the platelet population.25 Addition of collagen to whole blood obtained from PCI patients at baseline or from normal volunteers gave a large 6 to 20-fold increase in annexin-V binding (30% positive platelets). The collagen-induced increase in annexin-V binding was significantly inhibited in the platelets obtained from the PCI patients after 30 min of bivalirudin infusion or by spiking whole blood from healthy volunteers with bivalirudin (Figure 5A-B).

Figure 5.

Bivalirudin inhibits collagen-induced platelet procoagulant activity and thrombin generation. (A) Whole blood from PCI patients (n=5) at baseline or 30 min after initiation of PCI was diluted 10-fold into Hepes buffer and was incubated with the indicated agonists (5 μg/ml collagen, 20 nmol/L thrombin, or 5 μg/ml collagen plus 20 nmol/L thrombin). After 15 min, the platelet samples were stained with an annexin V-antibody and % platelets staining (M1 region) with the anionic phospholipid marker quantified as described in the Methods. (B) Whole blood from healthy donors were diluted as the patient samples in A and preincubated with the indicated concentrations of bivalirudin (μmol/L) or 100 μmol/L PPACK before addition of collagen and/or thrombin agonists. The percentage of annexin V binding positive (M1) for both healthy donors (n=6) and patients (n=5) are shown (mean ± SD). (C) PRP from a healthy donor was preincubated in the presence or absence of 5 μmol/L bivalirudin for 2 min before the addition of 5 μg/ml collagen. The amounts of thrombin generated (mean ± SD of triplicate samples) were determined as described in the Methods. The experiment was done with 2 other healthy donors and gave similar results. ˆ P< 0.025, # P< 0.017, ## P< 0.001 by paired-sample t test with Bonferroni correction and * P < 0.05 by paired-sample t test.

Consistent with previous data,26 thrombin gave a 2-fold increase in annexin-V positive platelets, which was inhibited in the whole blood obtained from PCI patients after 30 min bivalirudin infusion or by addition of bivalirudin to whole blood from healthy volunteers. The combination of collagen plus thrombin gave a synergistic enhancement in annexin-V binding which was inhibited by bivalirudin in the PCI patients and by exogenously-added bivalirudin in the normal volunteers. Likewise, the direct thrombin inhibitor, PPACK, completely blocked annexin-V staining in response to collagen or thrombin (Figure 5B). Platelets in platelet-rich plasma from normal volunteers were then stimulated with collagen, and thrombin generation directly measured. As shown in Figure 5C, bivalirudin significantly inhibited thrombin generation triggered by exposure of the platelets to collagen. Together, these data indicate that bivalirudin can suppress collagen-induced platelet aggregation by blocking thrombin-dependent propagation of procoagulant activity on the platelet surface.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that bivalirudin at the dose currently utilized during PCI, provides extensive protection from thrombin-induced platelet aggregation. At this dose, bivalirudin also suppressed systemic thrombin-antithrombin III levels by more than half and significantly inhibited collagen-induced platelet aggregation and generation of platelet thrombogenic surfaces. These findings demonstrate that bivalirudin has a hitherto unappreciated ability to inhibit both protease-activated receptor and collagen-dependent aggregation and platelet procoagulant activity in patients undergoing PCI. We also provide the first direct evidence that bivalirudin protects against thrombin cleavage of PAR1 on the platelet surface in PCI patients.

Bivalirudin has become a widely used adjunctive therapy in a broad spectrum of patients with coronary artery disease undergoing PCI. Large clinical trials have documented the efficacy of bivalirudin as compared to heparin plus GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors.4, 5 Our study provides a mechanistic framework to suggest efficacy of bivalirudin as it relates to platelet-dependent ischemic events. Thrombin is the most potent stimulator of platelet activation and thrombosis.7, 27 Thrombin triggers platelet aggregation through the dual actions of both the PAR1 and PAR4 receptors.7 PAR1 is a high-affinity receptor for thrombin by virtue of a hirudin (Hir)-like sequence that resides in its N-terminal extracellular domain.19, 28, 29 The Hir sequence allows PAR1 to compete with the much more abundant fibrinogen, and as a result, PAR1 is activated by thrombin at sub-nanomolar concentrations. The present study showed that bivalirudin effectively suppressed cleavage of the extracellular domain of PAR1 on the platelet surface by even supra-physiologic concentrations of 50 nM thrombin.

After cleaving PAR1, thrombin may remain tethered to PAR1 through the Hir sequence where it can cleave nearby PAR4 which exists as a heterodimer in association with PAR1.8, 19 PAR4 is cleaved more slowly than PAR1 mainly because it lacks a functional Hir sequence30 and relies on PAR1 to play this critical helper function.8 Thus, the hirudin analog bivalirudin is an effective inhibitor of the interactions of thrombin with both PAR1 and PAR4. Given that the steady-state levels of bivalirudin achieved during PCI achieved complete blockade of 50 nM thrombin-induced platelet activation, this study would strongly suggest that bivalirudin suppresses both PAR1 and PAR4-dependent platelet activation during PCI. The described effects of bivalirudin-mediated inhibition of thrombin-induced platelet aggregation with an absence of an effect on SFLLRN or AYPGKF indicates that the inhibitory effects of bivalirudin depends on its ability to prevent upstream thrombin activation of the platelet thrombin receptors but, as expected, does not affect platelet aggregation triggered by either of the synthetic PAR1 or PAR4 agonist peptides which bypass the requirement for thrombin cleavage.19

The present study determined that the mean half-life of bivalirudin in the PCI patients was 29 minutes, which is approximately one-third the half-life of unfractionated heparin and is significantly less than the biological half-lives of the three commonly used GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors.31 This rapid disappearance of bivalirudin from the plasma likely contributes to the relatively low incidence of acute bleeding complications observed in PCI patients that receive bivalirudin monotherapy, as compared to patients that receive the longer-lived heparin and GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors.

We also provided evidence that bivalirudin negatively regulates on-going thrombin generation in PCI patients. Systemic thrombin, as reflected by antithrombin III-thrombin levels was significantly suppressed by bivalirudin in nearly all patients during the PCI procedure and did not rebound above baseline levels 2 hours after the bivalirudin infusion was terminated. Moreover, the vast majority of patients had post-procedural TAT levels that remained significantly suppressed at 2 hours as compared to baseline. These data support the notion that bivalirudin targets both existing circulating thrombin and interrupts on-going procoagulant activity.

In this regard, we found that bivalirudin suppressed thrombin generation by blocking collagen-initiated platelet procoagulant activity. GPVI is the major collagen receptor that is a highly efficient activator of platelet procoagulant activity.32 Indeed, previous studies showed that exposure of platelets to collagen lead to the appearance of a high percentage of negatively-charged phospholipids, as reflected by annexin-V binding to the platelet surface.33, 34 The negatively charged phospholipids serve as a critical binding site for factor Va/Xa and accelerate the prothrombinase activity. The thrombin that is generated on the platelet surface in turn further activates platelets through the PARs26, 35, 36 and generates more prothrombinase activity by additional thrombin cleavage and activation of factor V. Bivalirudin attenuates this collagen-initiated platelet activation by inhibiting the thrombin positive feedback loop. However, it remains to be determined whether the observed 11% drop in mean collagen-induced platelet aggregation provides a clinically significant protective effect. Furthermore, it is unknown whether addition of a P2Y12 antagonist such as clopidogrel may either mask or augment these bivalirudin-mediated inhibitory effects on collagen in PCI patients.

Conflicting results have been reported on the efficacy of bivalirudin versus heparin on platelet function using FACS analysis. A recent study11 reported that heparin, but not bivalirudin inhibited sub-nanomolar thrombin cleavage and internalization of PAR1 on platelets from PCI patients. However, consistent with our earlier work8, a FACS study12 showed that spiked bivalirudin blocked thrombin activation of the GPII/IIIa receptor and surface expression of P-selectin to a much greater extent than spiking blood with heparin or heparin plus eptifibatide. Likewise, another report13 confirmed that bivalirudin completely blocks 10 nM thrombin activation of GPIIb/IIIa and P-selectin immediately after the PCI procedure.

In conclusion, we found that bivalirudin infusion during PCI confers a substantial inhibitory effect on both thrombin and collagen-mediated platelet activation and reduces plasma thrombin concentrations. These effects along with the short half-life of bivalirudin likely contribute to its efficacy and safety when used as an adjunctive agent during PCI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Nga Nyguen for blood sample preparation, Katie O’Callaghan for expert training in flow cytometry methods, and David Simon for performing statistical and power analyses.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported in part by a grant from The Medicines Company, and by grants from the NIH, R01-HL64701, RC2-HL101783 and R01-HL57905 (to A.K.).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no disclosures. The study sponsor, The Medicines Company, has a commercial interest in Bivalirudin. The sponsor had no input into the study design or analysis, nor in preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Warkentin TE, Greinacher A, Koster A. Bivalirudin. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:830–9. doi: 10.1160/TH07-10-0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harker LA. Strategies for inhibiting the effects of thrombin. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1994;5:S47–58. S59–64. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lincoff AM, Bittl JA, Harrington RA, Feit F, Kleiman NS, Jackman JD, Sarembock IJ, Cohen DJ, Spriggs D, Ebrahimi R, Keren G, Carr J, Cohen EA, Betriu A, Desmet W, Kereiakes DJ, Rutsch W, Wilcox RG, de Feyter PJ, Vahanian A, Topol EJ. REPLACE-2 Investigators. Bivalirudin and provisional glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade compared with heparin and planned glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade during percutaneous coronary intervention: REPLACE-2 randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:853–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.7.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone GW, White HD, Ohman EM, Bertrand ME, Lincoff AM, McLaurin BT, Cox DA, Pocock SJ, Ware JH, Feit F, Colombo A, Manoukian SV, Lansky AJ, Mehran R, Moses JW. Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage strategy (ACUITY) trial investigators. Bivalirudin in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a subgroup analysis from the Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage strategy (ACUITY) trial. Lancet. 2007;369:907–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone GW, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, Peruga JZ, Brodie BR, Dudek D, Kornowski R, Hartmann F, Gersh BJ, Pocock SJ, Dangas G, Wong SC, Kirtane AJ, Parise H, Mehran R. HORIZONS-AMI Trial Investigators. Bivalirudin during primary PCI in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2218–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurbel PA, Becker RC, Mann KG, Steinhubl SR, Michelson AD. Platelet function monitoring in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1822–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leger AJ, Covic L, Kuliopulos A. Protease-activated receptors in cardiovascular diseases. Circulation. 2006;114:1070–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.574830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leger AJ, Jacques SL, Badar J, Kaneider NC, Derian CK, Andrade-Gordon P, Covic L, Kuliopulos A. Blocking the protease-activated receptor 1-4 heterodimer in platelet-mediated thrombosis. Circulation. 2006;113:1244–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.587758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauer KA. Activation markers of coagulation. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 1999;12:387–406. doi: 10.1053/beha.1999.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Putten RF, Glatz JF, Hermens WT. Plasma markers of activated hemostasis in the early diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;371:37–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eslam RB, Reiter N, Kaider A, Eichinger S, Lang IM, Panzer S. Regulation of PAR-1 in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: effects of unfractionated heparin and bivalirudin. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1831–6. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider DJ, Keating F, Sobel BE. Greater inhibitory effects of bivalirudin compared with unfractionated heparin plus eptifibitide on thrombin-induced platelet activation. Coron Artery Dis. 2006;17:471–6. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200608000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider DJ, Sobel BE. Lack of early augmentation of platelet reactivity after coronary intervention in patients treated with bivalirudin. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2009;28:6–9. doi: 10.1007/s11239-008-0250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Covic L, Gresser AL, Kuliopulos A. Biphasic kinetics of activation and signaling for PAR1 and PAR4 thrombin receptors in platelets. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5458–67. doi: 10.1021/bi9927078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Meijden PE, Munnix IC, Auger JM, Govers-Riemslag JW, Cosemans JM, Kuijpers MJ, Spronk HM, Watson SP, Renné T, Heemskerk JW. Dual role of collagen in factor XII-dependent thrombus formation. Blood. 2009;114:881–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briede JJ, Tans G, Willems GM, Hemker HC, Lindhout T. Regulation of platelet factor Va-dependent thrombin generation by activated protein C at the surface of collagen-adherent platelets. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7164–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao AK, Pratt C, Berke A, Jaffe A, Ockene I, Schreiber TL, Bell WR, Knatterud G, Robertson TL, Terrin ML. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Trial--phase I: hemorrhagic manifestations and changes in plasma fibrinogen and the fibrinolytic system in patients treated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and streptokinase. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuliopulos A, Mohanlal R, Covic L. Effect of selective inhibition of the p38 MAP kinase pathway on platelet aggregation. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92:1387–93. doi: 10.1160/TH04-03-0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seeley S, Covic L, Jacques SL, Sudmeier J, Baleja JD, Kuliopulos A. Structural basis for thrombin activation of a protease-activated receptor: inhibition of intramolecular liganding. Chem Biol. 2003;10:1033–41. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robson R, White H, Aylward P, Frampton C. Bivalirudin pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: effect of renal function, dose, and gender. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;71:433–9. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.124522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bittl JA, Chaitman BR, Feit F, Kimball W, Topol EJ. Bivalirudin versus heparin during coronary angioplasty for unstable or postinfarction angina: Final report reanalysis of the Bivalirudin Angioplasty Study. Am Heart J. 2001;142:952–9. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.119374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Medicines Company. Angiomax (bivalirudin) Package Insert (NDA 20-873 label) 2005 Available at http://www.themedicinescompany.com/pdf/ANG-PPO-295-02.pdf.

- 23.Trivedi V, Boire A, Tchernychev B, Kaneider NC, Leger AJ, O’Callaghan K, Covic L, Kuliopulos A. Platelet matrix metalloprotease-1 mediates thrombogenesis by activating PAR1 at a cryptic ligand site. Cell. 2009;137:332–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gurbel PA, Murugesan SR, Lowry DR, Serebruany VL. Plasma thromboxane and prostacyclin are linear related and increased in patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1999;61:7–11. doi: 10.1054/plef.1999.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dormann D, Clemetson KJ, Kehrel BE. The GPIb thrombin-binding site is essential for thrombin-induced platelet procoagulant activity. Blood. 2000;96:2469–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersen H, Greenberg DL, Fujikawa K, Xu W, Chung DW, Davie EW. Protease-activated receptor 1 is the primary mediator of thrombin-stimulated platelet procoagulant activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11189–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weitz JI, Hudoba M, Massel D, Maraganore J, Hirsh J. Clot-bound thrombin is protected from inhibition by heparin-antithrombin III but is susceptible to inactivation by antithrombin III-independent inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:385–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI114723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vu TK, Wheaton VI, Hung DT, Charo I, Coughlin SR. Domains specifying thrombin-receptor interaction. Nature. 1991;353:674–7. doi: 10.1038/353674a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacques SL, LeMasurier M, Sheridan PJ, Seeley SK, Kuliopulos A. Substrate-assisted catalysis of the PAR1 thrombin receptor. Enhancement of macromolecular association and cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40671–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacques SL, Kuliopulos A. Protease-activated receptor-4 uses dual prolines and an anionic retention motif for thrombin recognition and cleavage. Biochem J. 2003;376:733–40. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madan M, Berkowitz SD, Tcheng JE. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa integrin blockade. Circulation. 1998;98:2629–35. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.23.2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nieswandt B, Watson SP. Platelet-collagen interaction: is GPVI the central receptor? Blood. 2003;102:449–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heemskerk JW, Vuist WM, Feijge MA, Reutelingsperger CP, Lindhout T. Collagen but not fibrinogen surfaces induce bleb formation, exposure of phosphatidylserine, and procoagulant activity of adherent platelets: evidence for regulation by protein tyrosine kinase-dependent Ca2+ responses. Blood. 1997;90:2615–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dale GL. Coated-platelets: an emerging component of the procoagulant response. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:2185–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keuren JF, Wielders SJ, Ulrichts H, Hackeng T, Heemskerk JW, Deckmyn H, Bevers EM, Lindhout T. Synergistic effect of thrombin on collagen-induced platelet procoagulant activity is mediated through protease-activated receptor-1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1499–505. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000167526.31611.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dorsam RT, Tuluc M, Kunapuli SP. Role of protease-activated and ADP receptor subtypes in thrombin generation on human platelets. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:804–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.