Abstract

Little research has been conducted to examine the influence of exposure to televised sexual content on adolescent sexuality or how parental intervention may reduce negative effects of viewing such content. This study uses self-report data from 1,012 adolescents to investigate the relations among exposure to sexually suggestive programming, parental mediation strategies, and three types of adolescent sexuality outcomes: participation in oral sex and sexual intercourse, future intentions to engage in these behaviors, and sex expectancies. As predicted, exposure to sexual content was associated with an increased likelihood of engaging in sexual behaviors, increased intentions to do so in the future, and more positive sex expectancies. Often, parental mediation strategies were a significant factor in moderating these potential media influences.

Keywords: adolescent sexuality, media effects, parental mediation, sexual content, television exposure

Over the past three decades, a large literature has amassed regarding the potential negative influences of viewing televised sexual content on adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behavior. Much of the concern about television sex has been based on content analyses that have documented high levels of sexual behavior and talk that are seldom accompanied by messages about risks or negative consequences (e.g., Brown & Witherspoon, 2002; Cope-Farrar & Kunkel, 2002; Fisher, Hill, Grube, & Gruber, 2004; Kunkel et al., 1999, 2003; Kunkel, Cope-Farrar, Biely, Maynard-Farinola, & Donnerstein, 2001; Kunkel, Eyal, Finnerty, Biely, & Donnerstein, 2005; Ward, 2003). For example, a recent content analysis found that 82.1% of episodes coded contained sexual content; however, only 2.9% of episodes with sex contained messages about sexual patience, and 5.2% had messages about taking sexual precautions (Fisher et al., 2004). Fewer studies have examined the effects of young people’s exposure to televised sexual content. Recent investigations have found that use of high sexual content media predicts the likelihood of engaging in sexual intercourse and the progression to more advanced noncoital sexual activity (Brown et al., 2006; Collins et al., 2004; Martino et al., 2006). Studies of parents’ strategies for intervening in their children’s television viewing, or parental mediation, are absent from the literature on media and adolescent sexual behavior.

Parental mediation has been conceptualized as a multidimensional construct often comprised of (1) active or instructive mediation (talking with children about television), (2) restrictive mediation (setting rules and limits on television viewing), and (3) coviewing (watching television with children) (Buerkel-Rothfuss & Buerkel, 2001; Nathanson, 2001a; Valkenburg, Kremar, Peeters, & Marseille, 1999; Warren, Gerke, & Kelly, 2002). Several theoretical perspectives highlight the importance of parents in understanding the effects of media messages on youth. The Message Interpretation Process (MIP) model, for example, posits several successive processes that occur between young people’s exposure to televised messages and their later behavior (i.e., determining whether a portrayal seems realistic or normative, and then assessing its perceived similarity to one’s personal experience) (Austin, 2001; Austin, Roberts, & Nass, 1990). According to the model, to the extent that parents’ discussions of television portrayals with youth can cultivate skepticism, they can reduce perceived desirability and similarity, and thus decrease effects of media on risky behavior (Austin, 2001; Austin et al., 1990). Nathanson (1999) theorizes that parents’ discussion of television content, as well as their use of restrictive mediation and coviewing, signal to the child the value of and attention that should be accorded to television messages. Thus, parents’ interactions with children about television content serve to enhance or diminish youths’ attention to and appraisals of content, which influence behavior and risk-taking. This study tests whether, consistent with MIP and other models, the use of parental mediation strategies modifies the outcomes of young people’s exposure to high sexual content television.

Youth Sexual Socialization

Parental Influences

Sexual socialization is the intricate and gradual process by which young people acquire knowledge, attitudes, and values about sexuality through the integration of information from multiple sources (Ward, 2003). Foremost among these sources are youths’ parents. Perceived and actual parental attitudes toward sexuality are strong predictors of adolescent sexual behavior, with parental disapproval inversely associated with initiation and frequency of vaginal intercourse in cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses (Dittus & Jaccard, 2000; Jaccard, Dittus & Gordon, 1996; Resnick et al., 1997). In studies of parental communication, more comprehensive discussions about sexuality with one’s mother were inversely associated with the initiation of vaginal intercourse (DiIorio, Kelley, & Hockenberry-Eaton, 1999), and higher levels of mother-daughter sexual risk communication were significantly associated with a lower frequency of vaginal intercourse and more consistent contraceptive use (Hutchinson, Jemmot, Jemmot, Braverman, & Fong, 2003). Parental monitoring of young people’s behavior has been inversely associated with the initiation of sex in adolescents (Longmore, Manning, & Giordano, 2001) and sexual risk-taking such as nonuse of condoms or having multiple sex partners (Cohen, Farley, Taylor, Martin, & Shuster, 2002; Huebner & Howell, 2003).

Television Influences

Along with parents, the media—and television in particular—have received substantial attention as potentially important sources of information about sex (Collins, 2005; Collins, Elliott, Berry, Kanouse, & Hunter, 2003; Ward, 2003). In a national survey, 70% of teens aged 15 to 17 reported having learned “a lot” or “some” about relationships and sexual health issues from the media (Hoff, Greene & Davis, 2003). With sexual issues often presented in a positive, compelling and explicit manner, sexual portrayals on television may capture the interest and attention of youth more effectively than other socializing agents.

In addition to their engaging nature, incidents of sexual behavior and talk about sex on television are pervasive (Fisher et al., 2004; Kunkel et al., 1999, 2001, 2003, 2005), with the average American youth exposed to nearly 14,000 sexual references, innuendos, and behaviors on television annually (Strasburger, 2004). Thus, television programming offers many opportunities for learning about sexual issues that are often not available elsewhere (e.g., how to perform a specific sexual behavior, how to talk to a potential sexual partner). According to social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986, 2001), individuals will imitate the behavior of others, including media models, when those behaviors are rewarded or even unaccompanied by negative consequences. Because media portrayals of sex tend to be predominately favorable—typically focusing on the positive aspects of sex rather than problems and risks (Fisher et al., 2004; Kunkel et al., 1999, 2001, 2003, 2005)—youth may be particularly likely to use such portrayals to guide their sexual behavior. In addition to providing behavioral models, exposure to television portrayals of sex may foster overly positive beliefs about youth sex, including misperceptions of the prevalence and likely outcomes of sexual activity among teens.

Parental Mediation

Parents’ interactions with their children about television take several forms. Active mediation is often operationalized as the frequency with which parents discuss whether and how television represents the real world, make critical comments about television messages, and provide supplemental information on topics introduced by television (Austin, 2001; Messaris, 1982). Some media researchers (e.g., Austin, Bolls, Fujioka, & Engelbertson, 1999) have distinguished positive active mediation from negative active mediation. The former takes into account that parents’ comments may reinforce rather than oppose negative television messages (such as violence or irresponsible sexual behavior). Discussions that endorse television messages should have very different effects from those comprised of negative active mediation, in which parental communication involves helping children understand the negative aspects of characters’ behavior, disagreeing with television messages, and explaining that television portrayals are unrealistic. Restrictive mediation involves establishing rules and limits about how much, when, and which types of television content can be viewed (Atkin, Greenberg, & Baldwin, 1991; Reid, 1979; Valkenburg et al., 1999; Weaver & Barbour, 1992). Coviewing involves parents watching television with their children without any discussion of content (Buerkel-Rothfuss & Buerkel, 2001; Valkenburg et al., 1999; Warren, 2003).

Among the three strategies, active mediation has received the most research attention. In an extensive review of the literature, Nathanson (2001a) reported that children who receive active mediation generally have been found to be more sophisticated and less vulnerable television viewers based on studies of four classes of outcomes—comprehension of or learning from television programs, social attitudes or perceptions, emotional responses, and real-world behaviors. Fewer studies on restrictive mediation have yielded some positive outcomes, such as increased comprehension of programs and an increased appreciation of television versus the real world (Desmond et al., 1985), less cultivation-like attitudes and perceptions (Rothschild & Morgan, 1987), and less aggression (Nathanson, 1999). Some evidence suggests, however, that high levels of restrictive mediation may backfire such that both very low and very high levels may be linked with negative consequences, such as more aggression (Nathanson, 1999). Little research has been conducted on parental coviewing and outcomes among youth. Although coviewing may increase children’s enjoyment and learning from educational programming (Salomon, 1977), several studies have found negative influences, including more stereotypical conceptions of sex roles and greater fear of the outside world (Rothschild & Morgan, 1987), more aggression in terms of day-to-day behavior (Nathanson, 1997) and behavior subsequent to viewing a violent cartoon (Nathanson, 1999), and a decreased ability to distinguish television characters from real people (Messaris & Kerr, 1984).

The processes through which parental mediation affects youth behavior are both explicit (e.g., direct communication about the reality status of portrayals, and approval or disapproval of characters’ behavior) and implicit (i.e., through the messages communicated about television as a source of information). Inferred attitudes about the value of the medium, how it should be used, and how much attention its content merits are proposed to help socialize children to an orientation toward television that shapes the degree to which they are affected by it (Nathanson, 1999). Active mediation that discounts or contradicts television messages and restrictive mediation are believed to convey to children that the discussed or prohibited content is not important, useful, or worthy of their attention. Coviewing in the absence of active mediation is believed to covey to children the opposite messages about the value of television. That children draw inferences from different mediation strategies is supported in several studies. Nathanson (2001b) found that restrictive mediation of violent content was interpreted by elementary school children as a sign that parents did not like such content or find it useful; In contrast, coviewing was perceived as an endorsement of the coviewed material. Interestingly, active mediation—measured simply as the frequency with which parents talked to their children about violent television programs—signaled parental approval of the content.

Most studies on parental mediation have gathered data from parents and young children, with little research focused on adolescents. To explore the impact of parental mediation on youth sexuality, a few studies have examined mediation and children’s attitudes and perceptions of traditional or stereotypical sex roles. It appears that only one study published to date has investigated the influences of television exposure and parental mediation on adolescent sexual behavior. Using data from White youth, Peterson Moore, and Furstenberg (1991) found no relationship between television viewing at ages 7 through 11 and subsequent sexual intercourse by age 15 or 16. Additional analyses were conducted to determine whether characteristics of the youth and of parent-child relationships—including frequency of discussing television, coviewing, and parental rules about television—were masking the influence of television; no such evidence emerged. Methodological limitations, however, such as using the overall amount of television viewed as a proxy for exposure to televised sexual content, make the null findings difficult to interpret.

This study uses data from 1,012 youth in early and middle adolescence to investigate the relations among exposure to televised sex, the three parental mediation strategies, and two sexual behaviors: oral sex and vaginal intercourse. Despite its risk for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), oral sex among youth has not been studied extensively. Nonetheless, analyses of the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth suggest that more teens aged 15 to 19 have ever engaged in oral sex (54%–55%) (Child Trends, Inc., 2005) than in vaginal intercourse (46%–47%) (Abma, Martinez, Mosher, & Dawson, 2004). A recent survey of ninth graders found that, compared to vaginal intercourse, youth reported more experience with oral sex, considered it more prevalent and acceptable among their peers, believed it to be less risky, and reported greater intentions to engage in it in the next 6 months (Halpern-Felsher, Cornell, Kropp, & Tschann, 2005). Previous research has demonstrated that sexual media effects are not linked to one sexual behavior exclusively (such as intercourse) but rather extend to noncoital sexual behaviors as well (Brown et al., 2006; Collins et al., 2004; Martino et al., 2006).

In addition to examining the relationships of exposure and mediation with sexual behavior, we also investigate their associations with young people’s sex expectancies (i.e., their beliefs regarding the likelihood of personally experiencing a variety of positive and negative consequences from engaging in vaginal intercourse) and future intentions to engage in sexual behavior. We hypothesize that viewing high sexual content material will be associated with greater involvement in oral sex and vaginal intercourse, greater intentions to engage in these 10 behaviors in the future, and more positive sex expectancies; overall television viewing is expected to be less strongly related to the three sexuality measures.

H1: Youth who report more as opposed to less exposure to high sexual content television are more likely to (1) engage in vaginal intercourse and oral sex, (2) report greater intentions to engage in these two behaviors in the next 12 months, and (3) have higher expectations for positive outcomes related to sexual intercourse and lower expectations for negative outcomes.

H2: Youth who report higher as opposed to lower levels of active and restrictive parental mediation will (1) be less likely to have had vaginal intercourse and oral sex, (2) report lower intentions to engage in these two behaviors in the future, and (3) report lower expectations for positive outcomes and higher expectations for negative outcomes related to sexual intercourse.

We also predict moderating effects for active and restrictive mediation, with high levels of parental mediation reducing the strength of the relationships between exposure to sexual content and the three sexuality measures: behavior, intentions, and expectancies.

H3: Under conditions of low levels of active and restrictive parental mediation, we expect exposure to high sexual content television to be (1) positively associated with participation in vaginal intercourse and oral sex, (2) positively associated with intentions to engage in these behaviors in the next 12 months, and (3) positively associated with expected positive outcomes related to sex and inversely related to negative outcome expectancies for sex. For youth with high levels of active and restrictive mediation, exposure will be less closely related to sexual behaviors, intentions, and expectancies.

Finally, because the findings for coviewing have been mixed, we pose the following research questions:

RQ1: Do youth who report higher levels of parental coviewing report less involvement in vaginal intercourse and oral sex, lower intentions to engage in these behaviors in the future, and lower expectancies for positive consequences and higher expectancies for negative outcomes of sex compared to youth who report relatively low levels of coviewing?

RQ2: Does parental coviewing moderate the relationship between exposure to televised sexual content and sexual outcomes such that under conditions of low levels of coviewing exposure is positively associated with engaging in vaginal intercourse and oral sex, greater intentions to engage in these behaviors in the next 12 months, and more positive and less negative sex expectancies, whereas the relations between exposure and these sexual outcomes are reduced under conditions of high levels of coviewing?

Method

Sample

The data were drawn from the second wave of a 3-year longitudinal study conducted in 10 counties in northern and southern California. A list-assisted sample of households from the greater San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles County in California was used to recruit study participants. Households were sampled from a purchased list of telephone numbers and addresses, which comprised households identified as likely to contain youth in the target age range. List-assisted sampling substantially increases efficiency, reducing costs, while producing samples comparable to those obtained through other techniques (Brick, Waksberg, Kulp, & Starer, 1995). Youth between the ages of 12 and 16 were recruited for the first survey and were re-surveyed at approximate 1-year intervals. Data were collected using a Computer Assisted Self-Interview (CASI) administered on a laptop in the home. The Wave 2 data were obtained over 3 months from September 2003 through November 2003.

Families were first contacted through a mailed letter and fact sheet that described the study. A telephone call was then used to schedule interviews. Up to 10 contact attempts were made before a number was retired from the sample. If a household included more than one eligible individual, the youth with the most recent birthday was selected. Active parental consent was obtained for all respondents as per the approved Institutional Review Board protocol.

At each in-home session, a trained interviewer showed the youth participant how to proceed through the computer program and then left him/her in a private location to complete the survey. The CASI instrument was designed to be gender specific and incorporate skip pattern logic. For example, boys were asked about their opposite-sex behavior with girls and their same-sex behavior with boys. In addition, if adolescents indicated they had not had sexual intercourse, they were skipped out of questions related to contraception. The CASI averaged 25 to 35 minutes to complete. Overall, 1,105 youth respondents completed the survey at Wave 1, for a response rate of 75% of estimated eligible households. The cooperation rate (N completed interviews/N known eligible households) was 88%. The final sample at Wave 2 comprised 1,012 of these 1,105 respondents, which represents a 93% retention rate.

Measures

Background

Respondents were asked to provide their gender and their current age. At the time of the Wave 2 survey, respondents ranged in age from 13 to 18 years (M = 15.1, SD = 1.43). Due to delays in survey administration, 15 Wave 2 participants had already turned 18. Gender was dummy coded (0 = female, 1 = male), with 48.4% females. Respondents chose from among eight racial/ethnic categories, which were then collapsed into two categories, White non-Hispanic (66.6%) or non-White (33.4%).

Hours per week of television

Respondents were asked how many hours of television they watched per day on weekdays (Mondays through Thursdays) and on weekend days (Fridays through Sundays). The responses to these two items were weighted and summed to produce a measure of total hours of television watched per week (Range 0 to 63, M = 22.0, SD = 14.5).

Frequency of viewing sexually suggestive broadcast programming

The CASI presented respondents with video clips from eight current fictional, nonanimated, prime time shows on network television to obtain measures of recognition and exposure during the past 6 months. The eight shows were selected because of their popularity among 12- to 17-year-olds based on television ratings provided by Nielsen Media Research and their high sexual content based on a separate content analysis conducted a few months before the survey (for a complete description of the content analyses, see Fisher et al., 2004). A 3-composite week sampling plan was used to randomly select days of the week for recording over about a 7-week period. Following Kunkel and colleagues (1999, 2001, 2003, 2005), sexual content was defined as any depiction of sexual activity, sexually suggestive behavior, or any talk about sexuality or sexual activity. Programs were coded in 2-minute intervals for the nature of sexual behaviors (e.g., kissing, intimate touching, and sexual intercourse), the explicitness of depictions (e.g., none, provocative or suggestive appearance, and disrobing), the types of sexual talk (e.g., talk about sexual interests, talk toward sex, and talk about past sexual intercourse), and talk frequency (e.g., a little—four or fewer comments; a lot—five or more comments). Sexual behaviors were weighted (with physical flirting given a weight of 1 and depictions of sexual intercourse assigned a weight of 5). Sexual talk categories were not weighted as there was no theoretical reason to believe that one type of talk should have more impact than another.

For each program episode, a sexual behavior subscore was calculated by multiplying the highest threshold sexual behavior coded per 2-minute interval by the explicitness value per interval, summing these products, and dividing by the number of 2-minute intervals. An overall sexual behavior score for each program series was obtained by taking the mean across the sampled episodes (e.g., 3 for a weekly series, 15 for a series broadcast on weekdays). A sexual talk subscore was also computed by summing the values of the focus on sexual talk variable across intervals and dividing by the number of 2-minute intervals. As with sexual behavior, an overall program series mean was calculated across program episodes. The final composite sexuality score for each series consisted of the sum of the average sexual behavior score and the average sexual talk score. All fictional, nonanimated series were sorted into four quartiles based on their composite sexuality scores. Shows were selected for the CASI that were highest ranked in the Nielsen ratings among 12- to 17-year-olds and fell in the third or fourth quartile of the program distribution based on sexuality scores.

The eight program series used in the Wave 2 CASI were According to Jim, Boston Public, Friends, My Wife and Kids, One on One, Scrubs, That 70’s Show, and Will and Grace. If respondents correctly identified what show a clip came from, they were asked how often they watched the show. Those who did not recognize the clip and those who said they had never watched the show all the way through to the end were assigned a viewing frequency score of 0 for that show. Otherwise, respondents reported how frequently they had watched the show during the past 6 months using a 4-point scale from not at all (1) to every time it’s been on (4). Frequency of viewing prime time shows was the sum of the frequency values across the eight shows. Thus, this variable had a potential range of 0 to 32 (Range 0 to 27, M = 7.1, SD = 4.9).

Frequency of viewing sexually suggestive cable programming

Four items assessed young people’s exposure to different genres of sexually laden cable programming appealing to youth audiences. Using nine categorical response options ranging from I do not watch (1) and less than 2 hours a week (2) to more than 20½ hours a week (9), respondents indicated how many hours per week they typically watched three types of cable programming: music videos; programs on HBO, Showtime, or Cinemax; and adult cable channels or adult pay per view movies. Response options were converted to hours per week ranging from 0 hours to 21 hours per week. A fourth item asked how many R or NC-17 movies respondents watched per week on cable or satellite television (1 = 0 movies, 6 = more than 10 movies). The highest category (6 = more than 10 movies) was conservatively assigned a value of 11 movies. The categorical response options were then converted to hours of viewing movies, assuming that the average movie was 1.5 hours long. A summary score was calculated across the four cable programming items to obtain a measure of total hours per week of exposure to sexually suggestive cable programming. This measure had a potential range from 0 to 79.5 hours per week (Range 0 to 46, M = 6.4, SD = 6.9).

Parental mediation of television viewing

Respondents answered seven items regarding how often their parents engaged in behaviors relating to the three mediation strategies using a 4-point scale from never (1) to very often (4). Based on prior research, a single item that asked youth how often their parents watched television with them served as the measure of coviewing (Range 1 to 4, M = 2.41, SD = .71). A principal axis factor analysis with an oblique rotation was performed on the six remaining items. We retained two factors with three items each. The parental limitation of television viewing (restrictive mediation) factor had an Eigenvalue of 2.4 and consisted of these items: parents check on television viewing; parents limit time watching television; and parents prohibit watching of certain shows (factor loadings of .62, .61, and .65, respectively). The parental discussion of television content (active mediation) factor had an Eigenvalue of 1.2 and consisted of these items: parents help child understand television content; parents suggest programs to learn more about sexuality, drugs and other issues; and parents discuss sex shown or talked about on television (factor loadings of .56, .51, and .60, respectively). The means of these items were used to create the parental limitation scale (α = .67, Range 1 to 4, M = 1.9, SD = .67) and the parental discussion scale (α = .61, Range 1 to 3.7, M = 1.4, SD = .48). Although these reliabilities are somewhat lower than those reported for longer scales measuring similar constructs with parents (e.g., Nathanson, 1999, 2002), they are in the generally acceptable range for brief scales used for survey research purposes (e.g., Streiner, 2003). Because they are somewhat low, effects for these variables may be underestimated.

Sexual behaviors

Respondents answered gender specific items regarding participation in two sexual behaviors using dichotomous response options (0 = no, 1 = yes). To assess oral sex, respondents were asked, “Have you ever had oral sex with a girl (boy)? [When a girl (boy) puts her (his) mouth or tongue on your genitals or you put your mouth or tongue on a girl’s (boy’s) genitals.”] To assess sexual intercourse, respondents were asked, “Have you ever had sexual intercourse? By sexual intercourse, we mean when a boy puts his penis into a girl’s vagina.”

Sexual intentions

Respondents were asked how likely or unlikely it was that, in the next 12 months, they would engage in oral sex (M = 1.7, SD = 1.12) or have sexual intercourse (M = 1.6, SD = 1.07). As the response options ranged from very unlikely (1) to very likely (4), higher scores represent greater intentions.

Sex expectancies

Respondents reported how likely or unlikely it was that they would experience each of 16 outcomes if they were to have sexual intercourse (1 = very unlikely to 4 = very likely). A principal axis factor analysis (see Table 1) suggested four expectancy factors: negative (e.g., lose self-respect, get in trouble with parents), positive (e.g., feel more grown up, be more popular), health (e.g., pregnancy, get an STD), and pleasure (e.g., have fun, enjoy it) expectancies. The means of these items were used to create scales representing negative expectancies (α = .83, Range 1 to 4, M = 2.8, SD = .84), positive expectancies (α = .80, Range 1 to 4, M = 2.2, SD = .80), health expectancies (α = .78, Range 1 to 4, M = 2.0, SD = .83), and pleasure expectancies (α = .91, Range 1 to 4, M = 3.1, SD = .93). For each expectancy scale, a higher score reflects a greater perceived likelihood that sexual intercourse would result in the designated type of outcome.

Table 1.

Pattern Matrix and Eigenvalues for Factor Analysis of Sex Expectancy Items

| Factors |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | Health | Pleasure | |

| Feel guilty | .73 | .04 | −.02 | −.07 |

| Get into trouble with parents | .55 | .01 | −.01 | .04 |

| Get a bad reputation | .66 | −.04 | .11 | −.09 |

| Lose self-respect | .68 | −.03 | .11 | −.16 |

| Disappoint people who are important | .74 | −.01 | −.03 | .08 |

| Be more popular | .01 | .52 | −.04 | −.03 |

| Feel more grown up | .04 | .77 | −.05 | −.06 |

| Feel more loved and wanted | −.10 | .79 | .05 | −.04 |

| Feel more attractive | .00 | .74 | .06 | .07 |

| Prevent breakup | .08 | .41 | .03 | .06 |

| Feel closer to partner | −.14 | .47 | −.03 | .15 |

| Pregnancy | .04 | −.02 | .54 | .15 |

| Sexually transmitted disease | −.03 | .04 | .94 | −.03 |

| HIV/AIDS | .03 | −.01 | .76 | −.18 |

| Enjoy | −.03 | .04 | .02 | .87 |

| Have fun | −.07 | .07 | −.03 | .86 |

| Eigenvalue | 4.8 | 2.9 | 1.6 | .98 |

Results

Correlations among media exposure and parental mediation variables were examined. The two measures of high sexual content viewing (i.e., on broadcast versus cable TV) were only weakly correlated (r = .20). Measures of exposure to sexually suggestive programming were moderately correlated with overall television viewing (Pearson correlations = .29 and .37, respectively for broadcast and cable TV). Correlations among the three parental mediation variables were positive and ranged from .30 to .36. Bivariate associations between parental mediation strategies and exposure measures were all weak, ranging from .00 to .13.

Binary logistic regression analyses were used for dichotomous outcomes (ever engaged in oral sex and ever engaged in vaginal intercourse), and ordinary least squares regressions were conducted on the continuous outcome measures (intentions to engage in sexual behaviors and sex expectancies). A hierarchical approach was used comparing four successive models predicting the sexuality outcome measures from television exposure and parental mediation. Model 1 included age, gender, race/ethnicity (White versus non-White), and total hours of television watched per week as predictors. Model 2 added the two high sexual content exposure variables: weighted frequency of viewing sexually suggestive broadcast shows and frequency of viewing sexually suggestive cable programming. Model 3 added the three parental mediation variables. Model 4 added all 6 two-way interactions for parental mediation and televised sex exposure. The final model was selected based on F-change (ΔF) and χ2-change (Δχ2) statistics. When Model 4 was the final model, interactions that were not significant were dropped.

Sexual Behavior—Ever Engaged in Oral Sex and Vaginal Intercourse

Less than a quarter of the sample had engaged in either behavior, with 23% and 17% having engaged in oral sex and vaginal intercourse, respectively. Despite small differences in respondents’ ages between samples, the prevalence rates we obtained for sexual intercourse are consistent with other recent surveys of California adolescents (e.g., California Health Interview Survey, 2005). Model 3 was the highest significant model for both engaging in oral sex (Cox & Snell Pseudo R2 = .21, Δχ2 (3, N = 1012) = 21.7, p < .001)) and intercourse (Cox & Snell Pseudo R2 = .17, Δχ2 (3, N = 1012) = 30.7, p < .001)). Older adolescents were significantly more likely to report ever having engaged in oral sex and intercourse (see Table 2). Adolescents who watched more television overall per week were less likely to have engaged in either behavior. In partial support of our hypothesis regarding exposure and sexual behavior, adolescents who watched more sexually suggestive cable programming were significantly more likely to report ever having engaged in oral sex and intercourse. Viewing sexually suggestive broadcast shows, however, was not a significant correlate of either behavior. Our prediction regarding main effects for parental mediation also received partial support. Adolescents who reported greater parental limitation of television viewing were significantly less likely to report having engaged in either oral sex or vaginal intercourse; however, no significant effects were found for parental discussion or coviewing. No exposure-parental mediation interactions emerged as significant.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Results for Predicting Experience with Oral Sex and Intercourse (N= 1012)

| Oral sex |

Intercourse |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | OR | CI | B | OR | CI | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Age | .68 | 1.97** | 1.71–2.27 | .68 | 1.98** | 1.67–2.32 |

| Gender (0 = female, 1 = male) | .16 | 1.17 | .83–1.66 | −.24 | .79 | .53–1.16 |

| Ethnicity (0 = non-White, 1 = White) | .11 | 1.12 | .79–1.59 | .13 | 1.14 | .77–1.67 |

| Hours per week of television | −.03 | .97** | .95–.98 | −.03 | .98* | .96–.99 |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Sexually suggestive broadcast shows | .03 | 1.03 | .99–1.07 | .03 | 1.03 | .98–1.07 |

| Sexually suggestive cable programming | .08 | 1.08** | 1.05–1.11 | .07 | 1.07** | 1.04–1.10 |

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Parental limitation of television | −.70 | .50** | .37–.68 | −.98 | .38** | .26–.55 |

| Parental discussion of television | .06 | 1.06 | .71–1.59 | .42 | 1.52 | .98–2.37 |

| Parental coviewing of television | .08 | 1.08 | .83–1.40 | .00 | 1.00 | .75–1.33 |

Note: For oral sex, Cox & Snell Pseudo R2 = .15 for Step 1; ΔR2 = .04 for Step 2; ΔR2 = .02 for Step 3 (ps <.001). For intercourse, Cox & Snell Pseudo R2 = .11 for Step 1; ΔR2 = .03 for Step 2; ΔR2 = .03 for Step 3 (ps <.001).

p < .05,

p < .001

Behavioral Intentions

Oral sex intentions

A quarter of adolescents (n = 253) reported that it was likely that they would engage in oral sex in the next 12 months. Of these, 73 (29%) had never engaged in oral sex. Model 4 was selected as the final model, accounting for 25% of the variance, ΔR2 = .02, ΔF (6, 999) = 4.54, p < .001. Adolescents who were older, White, and male reported greater intentions to engage in oral sex in the next 12 months (see Table 3). Overall television viewing was negatively related to this behavioral intention. Similar to the findings for the two sexual behaviors, youth who reported watching more sexually suggestive cable programming also reported greater intentions to have oral sex; however, sexually suggestive broadcast programming was not a significant correlate of oral sex intentions. The prediction for parental mediation and future intentions was supported regarding parental discussion only (with higher levels of this form of mediation associated with lower intentions).

Table 3.

Standardized Regression Coefficients (β) for Intentions to Engage in Oral Sex and Engage in Intercourse (N=1012)

| Intent to engage in oral sex | Intent to engage in intercourse | |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||

| Age | .32** | .33** |

| Gender (0 = female, 1=male) | .08* | .07* |

| Ethnicity (0 = non-White, 1 = White) | .09* | .03 |

| Hours per week of television | −.08* | −.07* |

| Step 2 | ||

| Sexually suggestive broadcast shows | .01 | .03 |

| Sexually suggestive cable programming | .19** | .17** |

| Step 3 | ||

| Parental limitation of television | .00 | −.18** |

| Parental discussion of television | −.16* | .02 |

| Parental coviewing of television | −.01 | .01 |

| Step 4 | ||

| Limitation X broadcast shows | −.36** | |

| Discussion X broadcast shows | .45** | |

Note: For oral sex intentions, R2 = .16 for Step 1; ΔR2 = .05 for Step 2; ΔR2 = .02 for Step 3; ΔR2 = .02 for Step 4 (ps <.001). For intercourse intentions, R2 = .17 for Step 1; ΔR2 = .04 for Step 2; ΔR2 = .03 for Step 3 (ps <.001).

p < .05,

p < .001

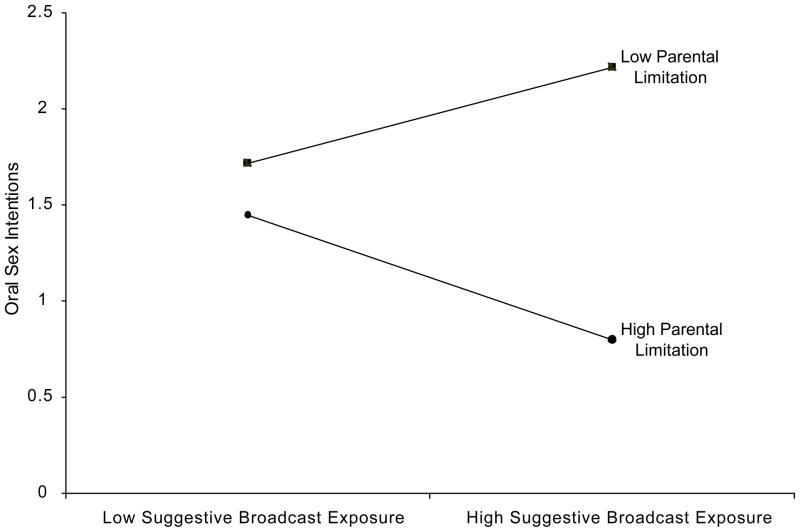

In addition, exposure to sexually suggestive broadcast shows had significant interactions with both parental limitation of television viewing and parental discussion of television content. Consistent with our hypotheses, there was a positive association between exposure to sexually suggestive broadcast programming and oral sex intentions among teens who reported low parental limitation. In contrast, exposure was negatively related to oral sex intentions among youth who reported high levels of parental limitation of viewing (see Figure 1). A different pattern emerged in the interaction with parental discussion of television content. Contrary to expectations, when parental discussion was low, there was little difference between the low and high exposure groups in intentions. Among youth who reported high parental discussion, however, a positive association emerged between exposure and future intentions for oral sex.

Figure 1.

Intent to Engage in Oral Sex: Parental Limitation and Suggestive Broadcast Interaction

Vaginal intercourse intentions

Two hundred and nineteen (22%) adolescents reported that it was likely that they would engage in vaginal intercourse in the next 12 months. Of these, 84 (38%) had never engaged in intercourse. Model 3 was selected as the final model for this measure, accounting for 23% of the variance, ΔR2 = .03, ΔF (3, 1005) = 11.84, p < .001. As shown in Table 3, the patterns of relations between sexual intercourse intentions and age, gender, and hours per week of television were identical to those for oral sex intentions. Similarly, more frequent viewing of sexually suggestive cable programming was also related to greater intentions to have intercourse, whereas exposure to sexually suggestive broadcast programming was not significantly related to intentions. In addition, some support emerged for the main effects of parental mediation. Adolescents who reported higher parental limitation of television viewing reported lower intentions to engage in intercourse in the next 12 months, whereas parental discussion and coviewing were not significant correlates.

Sex Expectancies

Negative expectancies

For negative expectancies, the final model was Model 3, which accounted for 33% of the variance, ΔR2 = .06, ΔF (3, 1005) = 29.37, p < .001. Adolescents who were older, male, and White reported lower negative expectancies (see Table 4); that is, they were less likely than younger, female, and non-White teens to believe that engaging in sex would result in adverse personal consequences. In contrast, youth who reported watching more hours of television overall per week reported higher negative expectancies. Partial support for the effects of high sexual content television was found as youth who watched more sexually suggestive cable programming reported lower negative expectancies. Partial support also emerged for the influence of parental mediation, with youth who reported higher parental limitation of television viewing also reporting higher negative expectancies. No such effect was found for discussion of television content or coviewing.

Table 4.

Standardized Regression Coefficients (β) for Sex Expectancies (N=1012)

| Negative expectancies | Positive expectancies | Health expectancies | Pleasure expectancies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||

| Age | −.22** | −.04 | −.09* | .21** |

| Gender (0 = female, 1=male) | −.33** | .28** | −.15** | .37** |

| Ethnicity (0 = non-White, 1 = White) | −.06* | .05 | −.03 | .09* |

| Hours per week of television | .06* | −.01 | .09* | −.04 |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Sexually suggestive broadcast shows | .02 | .15** | −.36* | .16** |

| Sexually suggestive cable programming | −.19** | .08* | −.19** | .08* |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Parental limitation of television | .22** | −.04 | .20* | −.10** |

| Parental discussion of television | .05 | −.03 | −.15* | −.02 |

| Parental coviewing of television | .02 | −.08* | −.04 | −.02 |

| Step 4 | ||||

| Limitation X broadcast shows | −.24* | |||

| Discussion X broadcast shows | .34* | |||

| Coviewing X broadcast shows | .33* | |||

Note: For negative expectancies, R2 = .24 for Step 1; ΔR2 = .04 for Step 2; ΔR2 = .06 for Step 3 (ps <.001). For positive expectancies, R2 = .07 for Step 1; ΔR2 = .03 for Step 2 (ps <.001); ΔR2 = .01 for Step 3, p <.01. For health expectancies, R2 = .06 for Step 1; ΔR2 = .04 for Step 2; ΔR2 = .02 for Step 3; ΔR2 = .02 for Step 4 (ps <.001). For pleasure expectancies, R2 = .20 for Step 1; ΔR2 = .03 for Step 2; ΔR2 = .01 for Step 3 (ps <.001).

p < .05,

p < .001

Positive expectancies

For positive expectancies, the final model was Model 3, which accounted for 11% of the variance in these beliefs, ΔR2 = .01, ΔF (3, 1005) = 4.50, p < .01. Male adolescents reported higher positive expectancies than females. Consistent with predictions, more positive expectancies about sex were reported by adolescents who watched more of both types of sexually suggestive programming. Although main effects did not emerge regarding parental limitation and discussion, adolescents who reported that their parents watched television with them more often were also less likely to believe that sex would result in positive outcomes than those who reported low levels of coviewing.

Health expectancies

For health expectancies, the final model was Model 4, which accounted for 13% of the variance in these beliefs, ΔR2 = .02, ΔF (3, 1002) = 4.37, p < .001. Adolescents who were older and male were less likely to report that sex would have health consequences. As with negative expectancies, perceptions about the likelihood of experiencing sexual health problems (e.g., pregnancy, HIV/AIDS) were positively associated with overall television viewing. Consistent with our hypotheses, adolescents who more often viewed both sexually suggestive broadcast shows and sexually suggestive cable programming were less likely to believe that sex would result in health problems. Also consistent with predictions, adolescents who reported higher levels of parental limitation reported higher expectancies for negative health outcomes. Contrary to predictions, youth who reported greater parental discussion of content reported lower expectancies regarding negative health consequences (see Table 4).

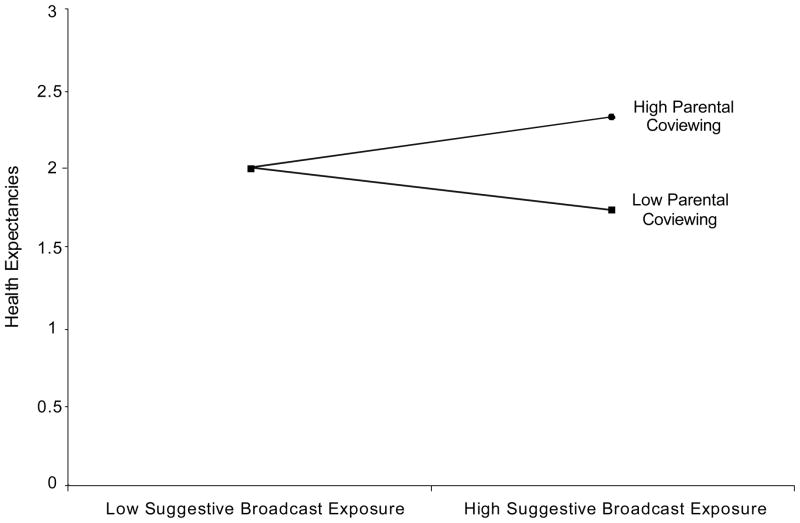

The main effect for exposure to sexually suggestive broadcast programming, however, was modified by significant interactions with all three parental mediation strategies. In each case, the expected form of the interaction was an inverse relation between exposure and health expectancies (i.e., greater exposure associated with a lower perceived likelihood of health consequences) for those with low mediation and little difference in health expectancies between exposure conditions for youth receiving high mediation. For parental limitation of viewing, an interaction of the opposite pattern emerged. Parental limitation was related to higher expectancies for sexual health consequences among those who were less exposed to televised sexual content but unrelated to these expectancies among those who were more exposed. For parental discussion, a crossover interaction emerged. When mediation was low, there was a slight negative relationship between exposure and expectancies; when mediation was high, however, exposure and expectancies were positively associated. As shown in Figure 2, the most theoretically consistent findings were obtained for the parental coviewing interaction. Youth who received low levels of this form of mediation reported lower perceived health consequences under high versus low exposure conditions. When parents coviewed more frequently, youth had somewhat higher expectations for health consequences from low to high exposure conditions.

Figure 2.

Health Expectancies: Parental Coviewing and Suggestive Broadcast Interaction

Pleasure expectancies

For pleasure expectancies, the final model was Model 3, which accounted for 25% of the variance in these beliefs, ΔR2 = .01, ΔF (3, 1005) = 5.51, p < .001. Adolescents who were older, male, and White reported greater beliefs that sex would result in pleasure. Support for our hypotheses regarding high sexually suggestive television programming was found. Higher pleasure expectancies were reported by adolescents who watched more of both types of sexually suggestive programming. Partial support was found for predictions about parental mediation. As expected, limitation of viewing was negatively associated with pleasure expectancies; however, no effects emerged for parental discussion or coviewing.

Discussion

Consistent with our hypotheses and with other recent research (e.g., Brown et al., 2006; Collins, 2005; Collins et al., 2003, 2004), this study provides evidence that exposure to sexual content on television is related to adolescents’ sexual behaviors and beliefs. Specifically, exposure to sexually suggestive cable television programming was related to an increased likelihood of having had oral sex and vaginal intercourse, increased intentions to engage in these behaviors in the next year, and a lower perceived likelihood that sexual intercourse would result in negative consequences and health problems. Similarly, exposure to sexually suggestive broadcast programming was related to decreased expectancies that sexual intercourse would have health-related consequences and to increased expectancies that it would lead to pleasure and positive consequences. These effects, although modest, were maintained after controlling for age, gender, ethnicity, and overall television viewing.

Importantly, parental mediation of children’s television viewing appeared to be a significant factor in countering these potential media influences. In particular, parents’ imposition of limits on program content and hours of viewing produced the greatest number of prosocial effects. Restrictive mediation was related to a reduced likelihood that a child had engaged in either oral sex or vaginal intercourse. These effects were surprisingly large. Similarly, restrictive mediation was negatively related to intentions to engage in vaginal intercourse in the future. Parental limitation was also related to increased expectations that sexual intercourse would lead to negative and health consequences and reduced expectations regarding pleasure. The relations between parental limitation of viewing and youths’ sexual beliefs and behaviors may represent the effects of such mediation, or they may reflect that parents who set limits or otherwise mediate in the viewing process are generally more disapproving of adolescent involvement in sexual behaviors and communicate this disapproval to their children. These parents may also set and enforce more rules in general for their children.

Parental discussion of content was negatively related to intentions to engage in oral sex but, unexpectedly, was also related to lower perceived likelihood of negative health consequences associated with vaginal intercourse. A possible reason for this latter finding may be that parents who discuss televised sexual content with their teens use such discussions as an opportunity to advise them on the use of condoms or other contraceptive methods. Future research should investigate in more detail the nature of parental discussion of television sexual content. Finally, parental coviewing was related to decreased expectations that sexual intercourse would have positive consequences, but this effect was small.

The overall pattern of findings is generally consistent with previous research and with theoretical explanations of the mediational process that focus on perceived importance and attention as mechanisms. In the case of parental discussion of content, for example, it has been suggested that such mediation may inadvertently increase the perceived importance of and attention paid to program content, thus sometimes leading to unintended effects. Importantly, however, when a program provides an educational message, parental coviewing may increase the effectiveness of that message. Thus, adolescent viewers of an episode of Friends that depicted a pregnancy resulting from a condom failure were more likely to change their beliefs about condom efficacy if they coviewed with a parent (Collins et al., 2003).

Importantly, the relations between television exposure and sexual beliefs were qualified by significant interactions with parental mediation. This was consistently the case for exposure to sexually suggestive material on broadcast television and health expectancies. However, the nature of these interactions varied by type of mediation. Surprisingly, parental limitation of viewing was related to higher expectancies for sexual health consequences such as STDs among those who were less exposed to sexually suggestive broadcast content but unrelated to these expectancies among those who were more exposed. Consistent with other findings (Nathanson, 1999), this pattern suggests that in some cases parental limitation may lead to unexpected outcomes. It may be that youth whose parents have strict household rules for television viewing find effective ways to circumvent them, such as by viewing at friends’ houses. If parental limits on viewing can be substantially thwarted, this may help explain the inverse relation between exposure and health expectancies under “high” mediation. Despite this unexpected pattern, youth who reported high parental limitation either perceived more health risks (under low exposure) or the same level of health consequences from sex (under high exposure) as those who received low limitation. Conversely, parental discussion was related to higher health expectancies among those who were more exposed but, unexpectedly, to lower health expectancies among those who were less exposed. Finally, coviewing was related to more negative health expectancies among those who were more exposed but unrelated to these beliefs among those who were less exposed.

Similar interactions between parental mediation and exposure to sexual content were found for intentions to engage in oral sex. As expected, exposure to sexually suggestive broadcast television was associated positively with these intentions for youth who reported low levels of parental limitation of viewing, whereas an inverse relationship occurred for those who reported high levels of parental viewing restrictions. Contrary to expectations, parental discussion was associated with higher intentions to have oral sex among those who were highly exposed to sexually suggestive broadcast television and lower intentions among those who were less frequently exposed. To the extent that parents’ discussions of sexual activity and associated risks, including those prompted by exposure to television portrayals, focus on vaginal intercourse and do not address oral sex, youth who experience high levels of this type of mediation are likely to have different appraisals—and thus expectancies and intentions—regarding these two sexual behaviors. In fact, several studies (Halpern-Felscher et al., 2005; Hoff et al., 2003; Hollander, 2005) have found that a substantial number of adolescents perceive oral sex to be safer and more acceptable than vaginal intercourse and report participating in oral sex as a strategy to avoid vaginal intercourse. Greater exposure and greater parental discussion were jointly associated with higher intentions for oral sex and increased perceptions regarding the health risks associated with vaginal intercourse. This suggests that such parent-child communications may focus on and reinforce the risks of intercourse, while making oral sex seem like a relatively safer alternative. If so, parents may need to broaden the scope of discussions about safer sex to include other intimate behaviors that pose health risks.

Several theoretical and conceptual approaches recognize the importance of parental mediation for moderating or reinforcing media messages. Importantly, parental mediation is not only posited to influence young people’s perceived similarity and identification with media messages, but their expectancies regarding the subject matter of programming that is mediated by parents (Austin et al., 1999, 2000, 2006). Our findings were generally consistent with this approach. Four of five significant main effects of parental mediation on expectancies were consistent with predictions by the MIP and other theoretical models—that is, greater mediation by parents was associated with increased negative and decreased positive expectancies.

Nonetheless, our findings also suggest that the effects of parental mediation may be more complicated than previous studies have allowed. In particular, the precise effects of mediation may depend upon the type of mediation, levels of exposure, and the outcome being considered. Parental coviewing and discussion may be more important for adolescents who are relatively more exposed to sexually suggestive television content and are interested in acquiring sexual information, including through media. In these cases, parents may play an important role in explaining or elaborating on the content, pointing out negative consequences or reinforcing desirable messages. Parental limitation of viewing may be more important for younger children (who are relatively less interested in seeking out sexual content), in part, because such rules may be internalized and carried over to other viewing situations later in life (Reid, 1979). Thus, the most important aspect of restrictive mediation may be its indirect and long-term implications for the socialization of children to an orientation toward television that makes them less vulnerable to its negative effects rather than its direct influences on exposure to objectionable content. Despite the complexities, however, several (albeit not all) of our findings suggest that parental mediation may have beneficial effects in reducing the influence of exposure to televised sex.

Although the bulk of prosocial findings for parental mediation in prior research have been linked with active mediation, in this study of youth sexuality, restrictive mediation emerged as the strategy most associated with desirable outcomes. These protective influences occurred across all three types of sexual outcomes: behavior, intentions, and expectancies. With our data, however, we cannot address whether this strategy was also associated with unintended effects that have emerged in other studies, such as negative attitudes toward parents or increased viewing of mediated content with friends (Nathanson, 2002). Consistent with previous research, we also found some support for the protective effect of active mediation, although half the results were in an unexpected direction. These mixed findings may have occurred in part because our measure did not separately assess negative versus positive active mediation.

Previous studies on parental coviewing are mixed with some studies finding no effects (e.g., Nathanson, 1999), whereas other studies have found coviewing to increase the effects of exposure (e.g., Collins et al., 2003; Nathanson, 2002). In our study, coviewing produced the fewest significant findings, with no effects on sexual behavior or intentions. The main effect on positive expectancies and the interaction on health expectancies, however, were consistent with an attenuating influence of parental coviewing on television messages regarding sex. Our measure of coviewing assessed the frequency with which parents watched television with their children but did not specify whether there was discussion. As coviewing may be interpreted by youth as parental endorsement of the coviewed material (Nathanson, 2001b), the moderating effect found for this strategy suggests that communication about content may be occurring.

An interesting pattern of results emerged for overall television viewing. Contrary to Collins and colleagues’ (2004) finding of no significant association between average hours of television viewing and sexual behavior, we found that youth who reported more frequent exposure to television in general were less likely to have had vaginal intercourse or oral sex and reported lower intentions to engage in either behavior in the future. These effects were mostly weaker than effects for high sexual content viewing and parental mediation. One possible explanation is that youth who spend more time watching television spend less time in social activities and have fewer opportunities to engage in sexual activities. Further, bivariate correlations suggest that although heavy viewers of television in general watched more sexually suggestive programming, they also have parents who were engaged in higher levels of parental discussion and coviewing. Additionally, despite the overwhelmingly positive light in which sex is typically shown with few depictions of risks and negative consequences (Aubrey, 2004; Fisher et al., 2004; Kunkel et al., 1999, 2001, 2003, 2005), high-volume viewers expressed stronger beliefs that sex would be associated with negative and health outcomes rather than less negative expectancies as predicted by media cultivation and other theories of media effects. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that parental efforts to interpret, elaborate, and provide supplemental information on topics introduced by television may counter the sex-promoting messages pervasive in program content.

Finally, it is important to note the developmental context in which parental mediation occurs. Like others, we found that age is positively related to the likelihood of having sex and future intentions to have sex, whereas it is inversely associated with perceived negative and health outcomes and positively associated with pleasure expectancies. This pattern suggests that, as children get older and are likely to be watching more explicit media, parents may want to focus on discussing content and pointing out the potential risks and consequences associated with sex. A transition from relying primarily on limitation of children’s viewing to discussion of content with adolescents not only would be consistent with age-related shifts in exposure to sexualized media, but also with the changes in cognitive development that permit youth in middle and late adolescence to better understand concepts of risk, consequences, and future planning. An important issue for future research will be to examine how age and sexual maturity may influence parental mediation strategies in relation to youths’ media use.

Our findings suggest the importance of both exposure to sexually suggestive television and parental mediation as a moderating influence; however, some shortcomings of this study must be noted. Most importantly, our analyses are based on cross-sectional data. Consequently, causal inferences are difficult. The fact that high parental discussion was related to increased oral sex intentions across exposure conditions could have occurred because parents of youth who are watching relatively high levels of televised sexual content engage in conversations because of concerns about this level of exposure or about the possibility that their child is becoming sexually active. Longitudinal analyses will be necessary to better answer questions regarding the directional nature of these relations. Further, although the percentages of youth in our sample who were sexually active were consistent with those from other large surveys in California, they may be somewhat lower than those reported from nationally representative samples. Differences across surveys in the age ranges of respondents, however, make this difficult to ascertain. To the extent that our sample was more conservative sexually than U.S. adolescents in general, our findings may not be generalizeable to all American youth. In addition to longitudinal designs, future studies with nationally representative samples would enhance our understanding of the effects of media exposure and parental mediation on adolescent sexuality.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grant Number HD038906 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD or NIH. An earlier version of this research was presented at the 113th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association in August 2005. The authors would like to thank Nielsen Media Research for providing the television rankings data. The authors also thank the coders who worked on the content analysis: Alicia Cohen, Ivette Hernandez, Kenneth Herrell, Jennifer Nitkowski Hill, Jennifer Kuhlman, David Lerner, Richard Lyght, Moira McCauley, Roshni Patel, Benjamin Pulz, David Salinger, Haniya Silberman, and Amanda Sole.

Contributor Information

Deborah A. Fisher, Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, Calverton, MD

Douglas L. Hill, Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, Calverton, MD

Joel W. Grube, Prevention Research Center, Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, Berkeley, CA

Melina M. Bersamin, Prevention Research Center, Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, Berkeley, CA

Samantha Walker, Prevention Research Center, Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, Berkeley, CA.

Enid L. Gruber, California State University, Fullerton, CA

References

- Abma JC, Martinez GM, Mosher WD, Dawson BS. Teenagers in the United States: Sexual activity, contraceptive use and childbearing, 2002. Vital Health Statistics. 2004;23(24):1–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin DJ, Greenberg BS, Baldwin TF. The home ecology of children’s television viewing: Parental mediation and the new video environment. Journal of Communication. 1991;41:40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Aubrey JS. Sex and punishment: An examination of sexual consequences and the sexual double standard in teen programming. Sex Roles. 2004;50:505–514. [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW. Exploring the effects of active parental mediation of television content. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 1993;37:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW. Effects of family communication on children’s interpretation of television. In: Bryant J, Bryant JA, editors. Television and the American Family. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 377–395. [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW, Bolls P, Fujioka Y, Engelbertson I. How and why parents take on the tube. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 1999;43:175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW, Chen MJ, Grube JW. How does alcohol advertising influence underage drinking? The role of desirability, identification and skepticism. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW, Pinkleton &, Fujioka Y. The Role of Interpretation Processes and Parental Discussion in the Media’s Effects on Adolescents’ Use of Alcohol. Pediatrics. 2000;105:343–349. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW, Roberts DF, Nass CI. Influences of family communication on children’s television-interpretation processes. Communication Research. 1990;17:545–564. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive approach. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology. 2001;3:265–299. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett JK, Papini DR, Gbur E. Familial correlates of sexually active pregnant and non-pregnant adolescents. Adolescence. 1991;26:458–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brick JM, Waksberg J, Kulp D, Starer A. Bias in list-assisted telephone samples. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1995;59:218–235. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, L’Engle KL, Pardun CJ, Guo G, Kenneavy K, Jackson C. Sexy media matter: Exposure to sexual content in music, movies, television, and magazines predicts black and white adolescents’ sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1018–1027. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, Newcomer SF. Television viewing and adolescents’ sexual behavior. Journal of Homosexuality. 1991;21(1/2):77–91. doi: 10.1300/J082v21n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, Steele JR. Sex and the mass media. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, Witherspoon EM. The mass media and American adolescents’ health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:153–170. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buerkel-Rothfuss NL. Background: What prior research shows. In: Greenberg B, Brown J, Buerkel-Rothfuss NL, editors. Media, sex, and the adolescent. Creskill, NJ: Hampton Press, Inc; 1993. pp. 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Buerkel-Rothfuss NL, Buerkel RA. Family mediation. In: Bryant J, Bryant JA, editors. Television and the American Family. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 355–376. [Google Scholar]

- Child Trends, Inc. Oral Sex. 2005 Retrieved April 15, 2008 from http://www.childtrendsdatabank.org/pdf/95_PDF.pdf.

- California Health Interview Survey. Data and findings. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2005. Retrieved October 14, 2005 from http://www.chis.ucla.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DA, Farley TA, Taylor SN, Martin DH, Shuster MA. When and where do youths have sex? The potential role of adult supervision. Pediatrics. 2002;111(6):1–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL. Sex on television and its impact on American youth: Background and results from the RAND Television and Adolescent Sexuality Study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinics of North America. 2005;3:371–385. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Elliott MN, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, Hunter SB. Entertainment television as a healthy sex educator: The impact of condom-efficacy information in an episode of friends. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1115–1121. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Elliott MN, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, Kunkel D, Hunter SB, Miu A. Watching sex on television predicts adolescent initiation of sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):e280–e289. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1065-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Sobol BL, Westby S. Effects of adult commentary on children’s comprehension and inferences about a televised aggressive portrayal. Child Development. 1981;52:158–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope-Farrar K, Kunkel D. Sexual messages in teens’ favorite prime-time television programs. In: Brown JD, Steele JR, Walsh-Childers K, editors. Sexual Teens, Sexual Media: Investigating Media’s Influence on Adolescent Sexuality. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Corder-Bolz CR. Mediation: The role of significant others. Journal of Communication. 1980;30(3):106–118. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond RJ, Singer JL, Singer DG, Calam R, Colimore K. Family mediation patterns and television viewing: Young children’s use and grasp of the medium. Human Communication Research. 1985;11:461–480. [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, Kelley M, Hockenberry-Eaton M. Communication about sexual issues: Mothers, fathers, and friends. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittus PJ, Jaccard J. Adolescents’ perceptions of maternal disapproval of sex: Relationship to sexual outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;26:268–278. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DA, Hill DL, Grube JW, Gruber EL. Sex on American television: An analysis across program genres and network types. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2004;48:529–553. doi: 10.1207/s15506878jobem4804_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Felsher BL, Cornell JL, Kropp RY, Tschann JM. Oral versus vaginal sex among adolescents: Perceptions, attitudes, and behavior. Pediatrics. 2005;115:845–851. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff T, Greene L, Davis J. National survey of adolescents and young adults: Sexual health knowledge, attitudes and experiences. Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander D. Many young teenagers consider oral sex more acceptable and less risky than vaginal intercourse. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2005;37:155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner AJ, Howell LW. Examining the relationship between adolescent sexual risk-taking and perceptions of monitoring, communication, and parenting styles. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33(2):71–78. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MK, Jemmot JB, Jemmot LS, Braverman P, Fong G. The role of mother-daughter sexual risk communication in reducing sexual risk behaviors among urban adolescent females: A prospective study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:98–107. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dittus PJ, Gordon VV. Maternal correlates of adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior. Family Planning Perspectives. 1996;28:159–165. 185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein JD, Brown JD, Childers KW, Oliveri J, Porter C, Dykers C. Adolescents’ risky behavior and mass media use. Pediatrics. 1993;92(1):24–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel D, Biely E, Eyal K, Cope-Farrar K, Donnerstein E, Fandrich R. Sex on TV. 3. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel D, Cope KM, Maynard-Farinola WJ, Biely E, Rollin E, Donnerstein E. Sex on TV: Content and context. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel D, Cope-Farrar K, Biely E, Maynard-Farinola WJ, Donnerstein E. Sex on TV. 2. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel D, Eyal K, Finnerty K, Biely E, Donnerstein E. Sex on TV. 4. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Longmore MA, Manning WD, Giordano PC. Preadolescent parenting strategies and teens’ dating and sexual initiation: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2001;63:322–335. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry DT, Towles DE. Prime time TV portrayals of sex, contraception and venereal diseases. Journalism Quarterly. 1989a;66(2):347–352. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry DT, Towles DE. Soap opera portrayals of sex, contraception, and sexually transmitted diseases. Journal of Communication. 1989b;39(2):76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Markham CM, Tortolero SR, Escobar-Chaves SL, Parcel GS, Harrist R, Addy RC. Family connectedness and sexual risk-taking among urban youth attending alternative high schools. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2003;35:174–179. doi: 10.1363/psrh.35.174.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino SC, Collins RL, Elliott MN, Strachman A, Kanouse DE, Berry SH. Exposure to degrading versus nondegrading music lyrics and sexual behavior among youth. Pediatrics. 2006;118:430–441. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messaris P. Parents, children, and television. In: Gumpert G, Cathcart R, editors. Inter/Media. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 1982. pp. 519–526. [Google Scholar]

- Messaris P, Kerr D. TV-related mother-child interaction and children’s perceptions of TV characters. Journalism Quarterly. 1984;61:662–666. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson AI. The relationship between parental mediation and children’s anti-and pro-social motivations. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association; Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 1997. May, [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson AI. Identifying and explaining the relationship between parental mediation and children’s aggression. Communication Research. 1999;26(2):124–143. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson AI. Mediation of children’s television viewing: Working toward conceptual clarity and common understanding. Communication Yearbook. 2001a;25:115–151. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson AI. Parent and child perspective on the presence and meaning of parental television mediation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2001b;45(2):201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson AI. The unintended effects of parental mediation of television on adolescents. Media Psychology. 2002;4:207–230. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Moore KA, Furstenberg FF. Television viewing and early initiation of sexual intercourse: Is there a link? Journal of Homosexuality. 1991;21(1–2):93–118. doi: 10.1300/J082v21n01_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid LN. Viewing rules as mediating factors of children’s responses to television commercials. Journal of Broadcasting. 1979;23:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Reiser RA, Tessmer MA, Phelps PC. Adult-child interaction in children’s learning from “Sesame Street. Educational Communication and Technology Journal. 1984;32:217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Reiser RA, Williamson N, Suzuki K. Using “Sesame Street” to facilitate children’s recognition of letters and numbers. Educational Communication and Technology Journal. 1988;36:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, Tabor J, Beuhring T, Sieving RE, Shew M, Ireland M, Bearinger LH, Udry JR. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:823–833. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild N, Morgan M. Cohesion and control: Adolescents’ relationships with parents as mediators of television. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1987;7:299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon G. Effects of encouraging Israeli mothers to co-observe Sesame Street with their five-year-olds. Child Development. 1977;48:1146–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Strasburger VC. Children, adolescents, and the media. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care. 2004;34:49–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner DL. Starting at the beginning: An introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2003;80:99–103. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg PM, Kremar M, Peeters AL, Marseille NM. Developing a scale to assess three styles of television mediation: “Instructive mediation,” “restrictive mediation,” and “social coviewing. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 1999;43:52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ward LM. Understanding the role of entertainment media in the sexual socialization of American youth: A review of empirical research. Developmental Review. 2003;23:347–388. [Google Scholar]

- Warren R, Gerke P, Kelly MA. Is there enough time on the clock? Parental involvement and mediation of children’s television viewing. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2002;46:87–111. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver B, Barbour N. Mediation of children’s televiewing. Families in Society. 1992;73:236–242. [Google Scholar]

- Warren R. Parental mediation of preschool children’s television viewing. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2003;47:794–417. [Google Scholar]