Abstract

The clinical translation of promising basic biomedical findings, whether derived from reductionist studies in academic laboratories or as the product of extensive high-throughput and –content screens in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries, has reached a period of stagnation in which ever higher research and development costs are yielding ever fewer new drugs. Systems biology and computational modeling have been touted as potential avenues by which to break through this logjam. However, few mechanistic computational approaches are utilized in a manner that is fully cognizant of the inherent clinical realities in which the drugs developed through this ostensibly rational process will be ultimately used. In this article, we present a Translational Systems Biology approach to inflammation. This approach is based on the use of mechanistic computational modeling centered on inherent clinical applicability, namely that a unified suite of models can be applied to generate in silico clinical trials, individualized computational models as tools for personalized medicine, and rational drug and device design based on disease mechanism.

Keywords: inflammation, mathematical model, sepsis, trauma, rational drug design, in silico clinical trial

THE TRANSLATIONAL DILEMMA AND RATIONAL DRUG DESIGN: EYOND THE CANDIDATES

The greatest challenge for the biomedical research community is the effective translation of basic mechanistic knowledge into clinically effective therapeutics, most apparent in attempts to understand and modulate “systems” processes/disorders, such as sepsis, cancer and wound healing. The United States Food and Drug Administration report: “Innovation or Stagnation: Challenge and Opportunity on the Critical Path to New Medical Products” (http://www.fda.gov/oc/initiatives/criticalpath/whitepaper.html), clearly delineates the steadily increasing expenditure on Research and Development concurrent with a steady decrease in delivery of medical products to market. This is the translational dilemma that faces biomedical research, and the current situation calls for a re-assessment of the scientific process as an initial step towards identifying where and how the process can be augmented by technology [An 2010].

The crux of the problem is that though many high-throughput techniques are used in modern drug discovery, both the traditional reductionism-based Scientific Method and the current regulatory framework generally focus on single molecules and genes as the targets of study and potential therapy development. The basic process flow of the Scientific Method is well known: observation (data collection), data analysis (identification of correlative relationships), hypothesis construction (inferences of mechanistic causality), and finally experimental testing (validation of hypotheses) to produce new data. The essential necessity of the Scientific Method cannot be questioned; however, attempting to address the current translational dilemma requires us to identify where the traditional Method is lacking, and how those areas may be addressed. The first step in this re-evaluation is to characterize the current contextual framework of knowledge and investigation, and to determine if, and how, the application of the Scientific Method can be improved. Towards this end, it is critical to note that advances in technology do not necessarily enhance each arm of the Scientific Method in an equal and matched fashion. The recent history (~ 25–50 years) of biomedical research provides a demonstration of this assertion. The introduction of molecular and cellular biology technologies prompted advances in experimental methods for data acquisition at increasingly finer levels of detail: increased resolution of imaging devices, high-throughput assays such as microarrays, gene knock-out cells lines and animals, and molecular manipulators like siRNA. At the other end of the spectrum, population-level data of increasing resolution became available, as the amount of information at each measurement point (i.e. the individual) dramatically increased in terms of both biological and epidemiological markers. Similarly, significant advances have taken place with regard to the development of powerful statistical tools, thereby enhancing the capacity to analyze this flood of data. Multivariate methods, such as linear regression, principal component analysis, clustering algorithms, and network constructors are all data analysis techniques that evolved as the density and dimensionality of datasets exploded. The power and sophistication of these correlative methods has allowed the discipline of statistics to evolve from a tool for the comparison of data sets to a means of using technology-generated insight as a substitute for traditional human intuition in the identification of potential relationships to be used in hypothesis formulation. This transition in the use of correlation-establishing methods is a critical point in understanding the scientific climate today. Therefore, it stands to reason that the augmenting the Scientific Method as it operates in our current knowledge landscape would be directed at increasing the “throughput” potential of hypothesis evaluation, and proceed with this as a specific goal of application development [An 2010].

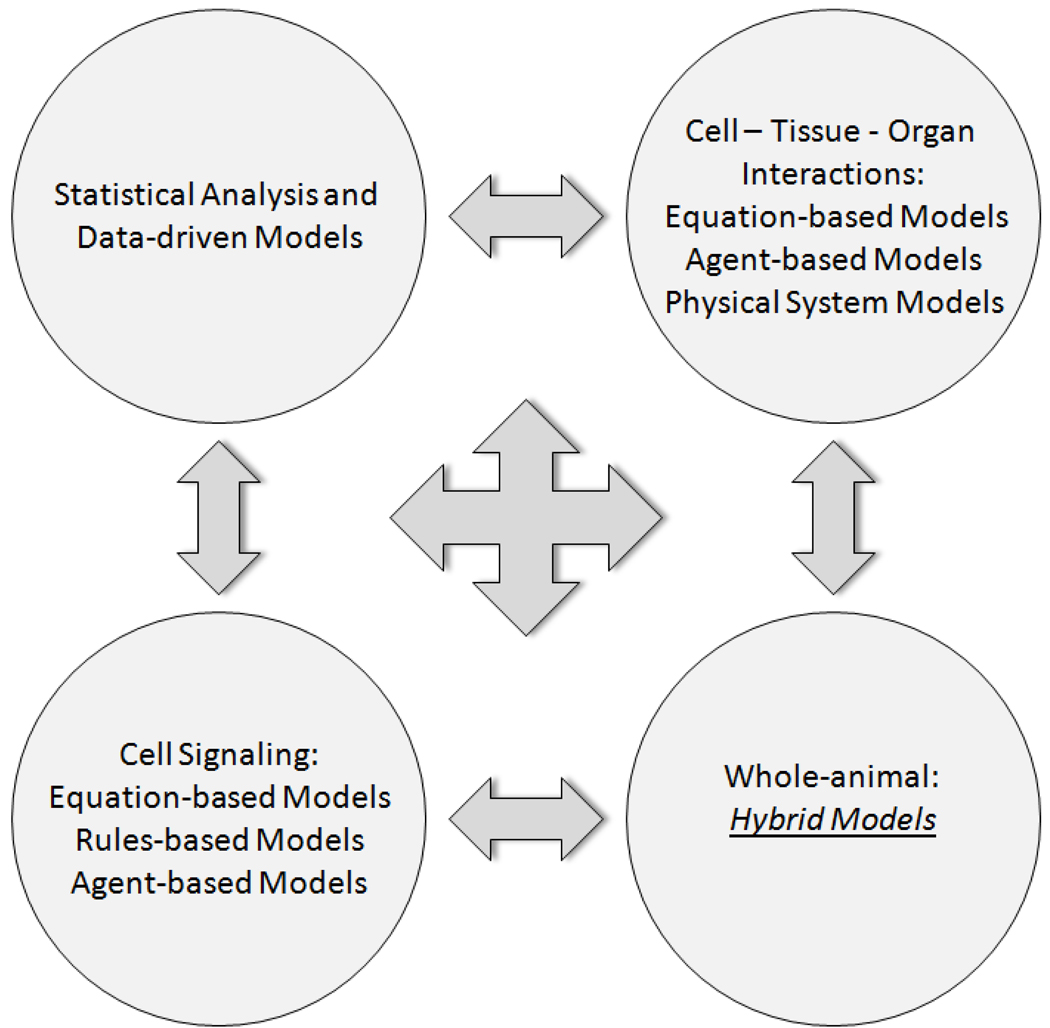

Given the limitations of purely data-driven analysis methods, an alternative and complementary approach is needed, one that focuses on the computational representation of the biological mechanisms that are the potential targets for manipulation and control. The past decade has yielded tremendous improvements in a set of tools that have been the cornerstone of physiology for 50 years. Though predominantly grounded in established mathematics, but augmented with newer rules- and agent-based methods along with hybrid models that integrate more than one modeling method in a single simulation, mechanistic computational simulations have the potential to meet the challenges outlined above [An et al. 2009; An and Vodovotz 2008; Vodovotz and An 2009; Vodovotz et al. 2009; Vodovotz et al. 2008]. As we illustrate below, data-driven methods and mechanistic simulations can be used in concert to gain predictive insights into processes of relevance to drug development, namely cellular signaling, cell/tissue/organ interactions, and effects at the whole-organism level (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Integration of data-driven and mechanistic modeling approaches to modeling disease.

Data-driven models may suggest principal drivers or dynamic networks involved in a given disease process, but must be linked via literature data or experiments to create mechanistic, dynamic computational simulations. These simulations may take different forms depending on the process and biological scale (sub-cellular, cellular, tissue, organ, whole-animal) being modeled.

Various in silico approaches have been used at multiple steps in the drug discovery and development pathway [Dearden 2007; Ekins et al. 2007a; Ekins et al. 2007b; Khakar 2010; Kirchmair et al. 2008; Merlot 2008; Pauli et al. 2008; van de Waterbeemd 2009; Vaz et al. 2010; Zoete et al. 2009], and most of these approaches are based strictly on data-driven modeling methods [Evans 2008; Huang 2002; Jenwitheesuk et al. 2008; Liao et al. 2008; Mandal et al. 2009; Nielsen and Schoeberl 2005; Wen and Fitch 2009; Wishart 2005]. Emerging bio-mechanistic simulations [Bruggeman and Westerhoff 2006; Michelson et al. 2006; Musante et al. 2002; Sanga et al. 2006; Vodovotz et al. 2008] are beginning to address the gulf between correlation and causality by emphasizing dynamic multi-scale representation of mechanisms, and thus characterizing the transition from health to disease. In this article, we discuss how advances in the field of biosimulation are helping fill the translational gap by addressing three defined components of the drug development pipeline: 1) evaluation of proof of concept early in the development process; 2) augmentation of and integration with existing traditional experimental procedures and data sets directed towards therapy development and evaluation, and 3) execution of in silico clinical trials, both for future trial planning as well as post hoc analysis and subgroup analysis. We believe that computational enhancement of these three areas represents a significant movement towards addressing the translational dilemma; taken together they fall under the umbrella of what we have termed Translational Systems Biology.

TRANSLATIONAL SYSTEMS BIOLOGY AND RATIONAL DRUG DEVELOPMENT

Translational Systems Biology involves a combination of clinically-focused modeling applications (such as in silico clinical trials), pre-clinical models that are based on data both obtainable in and useful for the clinical setting, and modeling-based drug design and screening (5, 6). In order to meet the translational challenge there is a need to modify computational simulation as currently implemented in order to bring focus on issues of direct clinical relevance. To date, the computational and systems biology community has utilized mathematical and simulation technologies in the study of subcellular and cellular processes [Csete and Doyle 2002; Kitano 2002], and this has been a major area of focus also for pharmaceutical industry [Rovira et al. 2010; Young et al. 2002]. While mechanistic computational modeling that “ends at the cell membrane” is inherently useful to an industry focused on screening for drugs that modulate specific pathways, this process is inherently dissociated from later steps in the drug development process. A given drug candidate must not only be identified in the most efficient way possible; this compound must also be passed through toxicity testing and clinical studies. While the mechanism of action of a given compound at the molecular/cellular level may, though mathematical modeling, be predictable with exquisite precision in highly controlled laboratory experiments, the effects of such a compound in vivo are in no way predictable from such models.

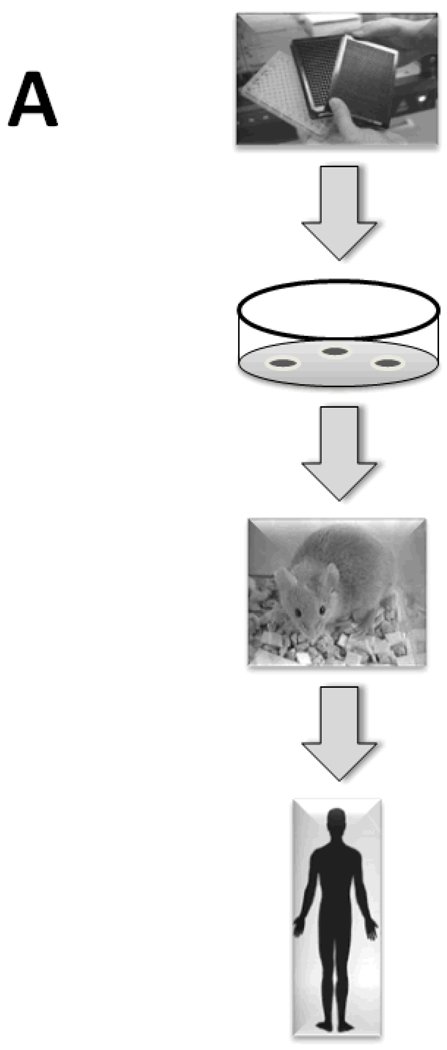

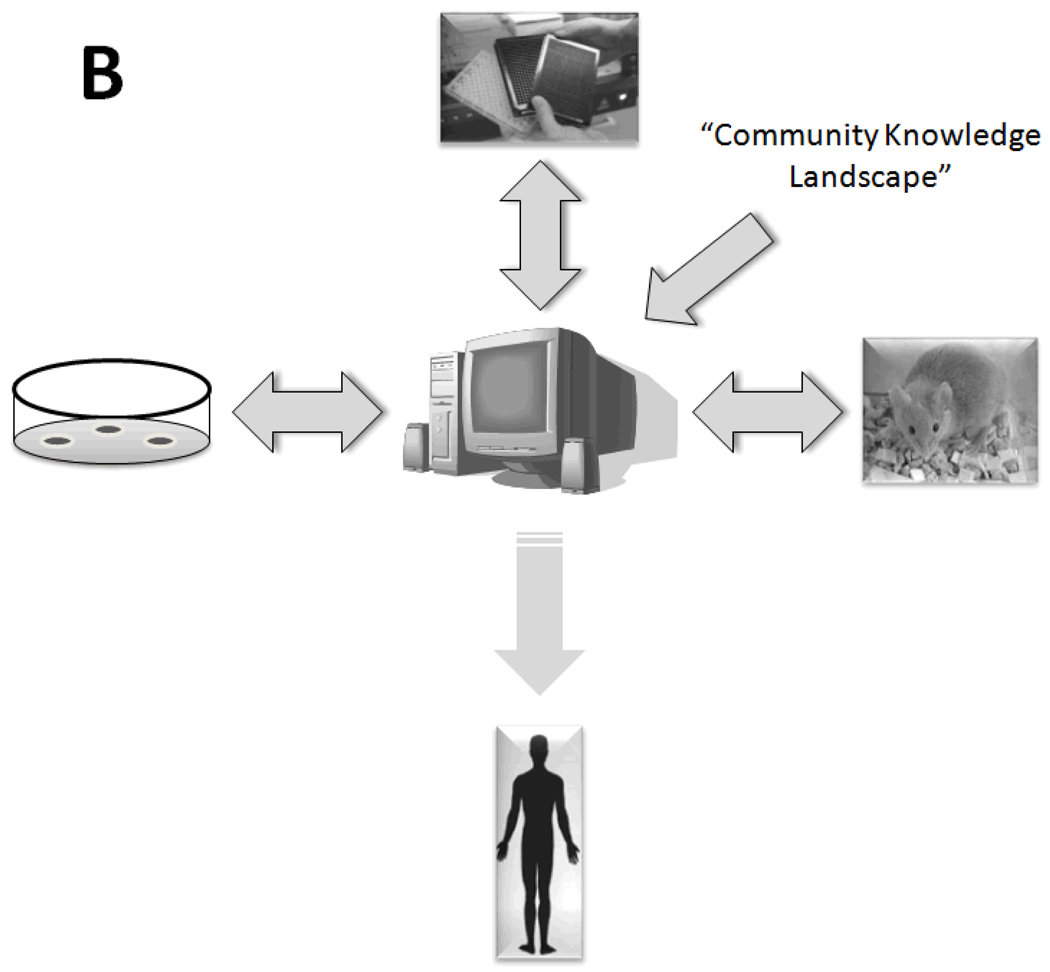

Therefore, Translational Systems Biology involves using dynamic mathematical modeling based on mechanistic information generated in early-stage and pre-clinical research to simulate higher-level behaviors at the organ and organism level, thus facilitating the translation of experimental data to the level of clinically relevant phenomena. One representative process by which computational modeling of experimental data could lead to rapid, parallelized clinical translation of drug candidates (as compared to the current serial process) is illustrated in Fig. 2. In this schema, the current linear, time-consuming, expensive, and failure-fraught system by which drug candidates are tested sequentially in vitro, in pre-clinical animal models, and subsequently through phased clinical studies (Fig. 2A) would be replaced with a system in which at every level of drug development a “reality check” against in silico clinical trials is carried out (Fig. 2B). If utilizing well-vetted computational models of human disease, the process should both reduce the time necessary to carry out a clinical trial and enhance the degree of confidence in the likelihood of success of a given drug candidate passing through the drug development pipeline. Below, we present a series of examples of Translational Systems Biology as applied to the acute inflammatory response in the settings of sepsis, trauma, hemorrhagic shock, and wound healing. This approach has been embraced by groups such as the Society of Complexity in Acute Illness (SCAI, website at http://www.scai-med.com). We do not mean to imply that such studies do not occur in other fields; however, the inflammation field is the first in which the Translational Systems Biology framework has been a guiding principle applied in a systematic fashion. We suggest that the Translational Systems Biology approach should be at the heart of the pharmaceutical industry’s standard operating procedures given the acute need and pragmatic pressure to discover novel drug candidates, vet their therapeutic ability, and streamline clinical trial design.

Figure 2. Current and proposed drug development process.

Panel A: the current drug development process is both serial and linear, progressing from high-throughput and high-content screening in vitro to testing of candidate compounds in animals and ultimately in clinical trials. Panel B: the proposed drug development process would be parallel and non-linear. It is envisioned that this process could start either from community consensus-based mechanistic computational models of disease, or from mechanistic computational models generated from a combination of high-throughput and high-content data and subsequent data-driven analyses such as Principal Component Analysis or Dynamic Network Analysis (see Fig. 1). In silico clinical trials based on such mechanistic computational models would then be the central component of a parallel process, in which predictions of drug properties and effects would be tested in pre-clinical animal models and subsequently in small clinical studies and ultimately in randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Importantly, the pre-clinical animal models would serve not as surrogates for the human disease, but rather as tests of the validity of the computational models underlying this new drug development process. While existing drug candidates could be screened in this fashion, ultimately the computational models could be used to define the properties of ideal drugs or devices for a given disease or patient sub-group, and the trials of such therapies could be based on individual-specific computational models.

ACUTE INFLAMMATION: EXAMPLE OF A THERAPEUTIC TARGET

The inflammatory response represents one of the most basic actions an organism can carry out: a response to injury and damage that leads to healing. It is highly evolutionarily conserved, and as manifest in mammalian organisms it is a well-coordinated communication network operating at an intermediate time scale between neural and longer-term endocrine processes [Nathan 2002; Vodovotz et al. 2008]. Inflammation is necessary for the removal or reduction of challenges to the organism and subsequent restoration of homeostasis [Nathan 2002]. However, disordered or inappropriate inflammation is associated with pathological conditions such as sepsis, trauma, inflammatory bowel diseases, chronic wounds, rheumatologic disorders and asthma; many other diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer’s, and obesity are also associated with dysregulated inflammation. Inflammation causes damage to tissues, which in turn leads to the production of molecules that re-stimulate inflammation. When this feed-forward loop spins out of control, it can lead to persistent, dysregulated inflammation that promotes organ dysfunction and death [Matzinger 2002; Nathan 2002; Rosenberg 2002; Schlag and Redl 1996; Stoiser et al. 1998; Vincent et al. 2000; Vodovotz et al. 2009]., likely in combination with failed attempts at therapy [Alverdy et al. 2005; Santos et al. 2005], Inflammation may also be driven by slower degenerative processes that share many common mediators with acute pro-inflammatory insults [Medzhitov 2008], perhaps thereby accounting for the pervasive role of inflammation in the complex diseases described above. Inflammation is therefore a logical drug target. However, one aspect that is often overlooked in the drug development process is that drug candidates, whether aimed at modulating inflammation or other processes, may have unforeseen effects in vivo based on their effects on the inflammatory response (e.g. gastrointestinal toxicity of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors [Borer and Simon 2005; Oviedo and Wolfe 2001] or increased susceptibility to infection in persons taking TNF-α inhibitors [Calabrese 2006; Rychly and DiPiro 2005]).

Below, we present examples of how Translational Systems Biology is being applied to the study of inflammation in various settings. A central theme of this article is that mechanistic computational simulations of diverse types may be differentially suited to particular modeling tasks. Another theme we will explore is the interplay between data-driven and mechanistic modeling (Fig. 1). As noted in Fig. 1, various aspects of acute inflammation and immunity have been simulated using diverse modeling approaches, including ordinary differential equation (ODE)-based approaches [Alt and Lauffenburger 1987; Arciero et al. 2010; Chow et al. 2005; Clermont et al. 2004a; Daun et al. 2008; Day et al. 2006; Foteinou et al. 2009a; Foteinou et al. 2009b; Kumar et al. 2008; Kumar et al. 2004; Lagoa et al. 2006; Prince et al. 2006; Reynolds et al. 2006; RiviŠre et al. 2009; Torres et al. 2009], agent-based approaches [An 2001; An 2004; An 2008; An 2009a; An 2009b; Dong et al. 2010; Li et al. 2008b; Mi et al. 2007; Solovyev et al. 2010], and rules-based approaches [An and Faeder 2009; Faeder et al. 2003; Goldstein et al. 2002]. Below, we present recent work that has focused on applying data-driven modeling techniques in combination with mechanistic modeling. Though beyond the scope of this article, details of these various modeling approaches, as well as their relative strengths and weaknesses, have been reviewed extensively elsewhere [An and Vodovotz 2008; Mi et al. 2010a; Vodovotz and An 2009; Vodovotz et al. 2004b; Vodovotz et al. 2007; Vodovotz et al. 2010; Vodovotz et al. 2009; Vodovotz et al. 2008]. In line with the schema presented in Fig. 1, we first examine studies utilizing knowledge and data-driven mechanistic modeling at the molecular/cellular level and at the tissue level. We then discuss how multi-scale modeling techniques are helping in the crucial process of translating modeling studies at the molecular and tissue levels to clinical useful insights at the whole-animal level, as well as the utility of both data-driven and mechanistic modeling at this higher level of organization. These insights include our increasing ability to predict the inflammatory responses of individuals. We then describe population modeling studies aimed at streamlining a key process in clinical translation, namely the clinical trial. We next discuss modeling studies aimed addressing an emerging area of interest in many fields, namely the complex host-pathogen ecology. Finally, we touch on the interface of in silico and synthetic biology, in which modeling studies are central to the rational design of drugs and devices targeted at the inflammatory response.

EARLY IN SILICO EVALUATION: HYPOTHESIS CHECKING AND TESTING PLAUSIBILITY

We propose that the greatest barrier to increasing the efficiency of drug development is not the identification of candidate molecules; rather, it is in the determination of whether the system-level consequences of attempting to intervene in a particular pathway will lead to a beneficial outcome, balancing safety vs. efficacy. In short, we seek a means to answer the question: “Is targeting this particular pathway a good idea?” Given the multi-scale complexity of the disease processes we seek to control, it is virtually impossible to make reliable inferences as to the reconstituted consequences of intervening at one selected point. While it is impossible to anticipate the unknown, we propose that it would be incredibly beneficial to be able to assess whether or not a particular hypothesis structure or conceptual mechanistic model is internally consistent and behaves as expected. We propose a computational means of “hypothesis checking” to identify and clarify the dynamic consequences of a particular conceptual model: a procedure by which static diagrammatic representations of conceptual models are brought “to life.” This has been termed dynamic knowledge representation, and is posited as a means of instantiating “thought experiments” such that the dynamic consequences of a particular hypothesis structure can be seen [An 2008; An 2010]. This process, at least in theory, allows a researcher to “check” his/her preconceived notions, to see if the particular mechanistic hypothesis actually behaves as expected. Dynamic knowledge representation has the potential to point out so-called “unanticipated” effects, which are in fact not unanticipated but rather ignored or underestimated effects of a given perturbation of a complex biological system. Dynamic knowledge representation may be augmented with insights derived from high-throughput and high-content data [An 2010], along with appropriate data analysis and data-driven modeling [Mi et al. 2010b; Vodovotz 2010; Vodovotz et al. 2010], to populate and calibrate dynamic computational models of a relevant disease, individual patient [Mi et al. 2010b], or patient population [Vodovotz and An 2009; Vodovotz et al. 2008] (Fig. 2).

An early example of this approach can be seen in a series of in silico simulated clinical trials of existing and hypothetical anti-mediator interventions for sepsis [An 2004; Clermont et al. 2004a]. A computational representations of the 1990s “state-of-the-art” conceptual model of the pathophysiology of sepsis, i.e. the conceptual model that informed the rationale behind the development of anti-pro-inflammatory cytokine therapies, was implemented in an agent-based model (ABM) [An 2001; An 2004]. While abstracted, this dynamic computational model reproduced the general disease dynamics of sepsis and multiple organ failure, and was used to generate a simulated population corresponding to the control group in a clinical sepsis trial. Then a series of existing [An 2004; Clermont et al. 2004a] and hypothetical [An 2004] mediator-based therapies were simulated in such as way that assumed that the proposed interventions behaved mechanistically exactly as had been hypothesized. Therefore, the simulated trials in the paper represented verification tests of the underlying hypotheses of action, avoiding the need to invoke any of the potentially confounding practical issues commonly used to explain negative clinical trial results (i.e. heterogeneity of adjunctive therapy, different pharmacodynamics/kinetics, faulty randomization, etc. -- the use of in silico clinical trials to address such practical challenges associated with a clinical study will be elaborated in a separate section below). As expected, none of the simulated interventions demonstrated a beneficial effect [An 2004; Clermont et al. 2004a], consistent with the results of the actual clinical trials. The conclusion drawn from these findings is that the underlying conceptual models that informed pharmaco-development were flawed. Furthermore, it is posited that had such a means of computational dynamic knowledge representation been available and used early in the drug candidate evaluation process, these flaws might have been recognized and blind therapeutic ends been avoided.

IN SILICO CO-DEVELOPMENT: INTEGRATION AND ITERATION

Much of the past work on Translational Systems Biology of inflammation was carried out using mechanistic modeling, and the computational models for those studies were developed subsequent to a thorough search of the relevant literature. Such combined in silico / in vivo studies in mice [Chow et al. 2005; Lagoa et al. 2006; Prince et al. 2006; Torres et al. 2009] and rats [Daun et al. 2008] have yielded many insights with regard to inflammation at the whole animal level, and are reviewed extensively elsewhere [Mi et al. 2010b; Vodovotz 2010; Vodovotz and An 2009; Vodovotz et al. 2006; Vodovotz et al. 2004b; Vodovotz et al. 2010; Vodovotz et al. 2009; Vodovotz et al. 2008]. The initial step in the development of these computational models, whether generated using equation- [Bailey 1998; Clermont et al. 2007; Edelstein-Keshet 1988 EDELSTEINKESHET1988; Neves and Iyengar 2002; Vodovotz et al. 2004b; Vodovotz et al. 2009; Vodovotz et al. 2008], agent- [An et al. 2009; Ermentrout and Edelstein-Keshet 1993; Grimm et al. 2005; Vodovotz et al. 2004b; Vodovotz et al. 2009; Vodovotz et al. 2008], or rule-based [Faeder et al. 2005; Hlavacek et al. 2006] computational techniques, was to integrate literature-derived information after a thorough evaluation/survey to determine a consensus on well-vetted mechanisms of inflammation; this process has been formalized as Dynamic Knowledge Representation [An 2008], as described above. More recently, we have sought to utilize data-driven approaches applied to prospective datasets representing the dynamics of inflammatory analytes, not only in order to avoid possible bias in selection of variables and mechanisms to include in mechanistic models, but also as an adjunct means for systems-based discovery [Mi et al. 2010b; Vodovotz 2010; Vodovotz et al. 2010]. We have begun to adopt an iterative process to which we had previously referred as “evidence-based modeling” [Vodovotz et al. 2006; Vodovotz et al. 2007], consisting of biomarker assay, data analysis/data-driven modeling to discern main drivers of a given inflammatory response [Janes and Yaffe 2006], literature mining to link these principal drivers based on well-vetted and likely mechanisms, calibration to the original data, and then validation using data separate from the calibration data [Mi et al. 2010b; Vodovotz 2010; Vodovotz et al. 2010].

Data-driven methods [Clermont et al. 2004b; Janes and Yaffe 2006; Vodovotz et al. 2004b], including network-based approaches [Bornholdt 2001; Chaouiya 2007; Chaplain and Anderson 2004; Christensen et al. 2007; Goncharova and Tarakanov 2007; Han 2008; Janes and Yaffe 2006; Lengeler 2000; Li et al. 2008a; Montague and Morris 1994; Neves and Iyengar 2002; Nikiforova and Willmitzer 2007; Rho et al. 2008; Stransky et al. 2007; Tekirian et al. 2007; Vogels et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2007], have indeed proven to be quite useful in systems biology applications. Principal components are orthonormal linear combinations of the data vector, with the property that they carry the largest variances in several orthogonal directions. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a method that reduces the dimensionality of a problem by concentrating on just a few (usually up to five or six) statistically most significant orthonormal linear combinations. These combinations are called the leading principal components. PCA has been used in various systems biology applications, among them attempting to define the main drivers of a biological process from measurements of a series of related variables (e.g. inflammatory cytokines). It is important to stress that PCA requires dynamic measurements. Moreover, while loosely-related variables might be assessed over time, any conclusions, hypotheses, or mechanistic computational models (see below) derived from PCA are likelier to be correct if the variables being measured relate to a defined biological process (e.g. inflammation). For example, Janes et al described the use of PCA to gain insights into the primary drivers of inflammation and apoptosis in an in vitro setting, based on a large number of dynamic measurements of apoptosis-related variables [Janes et al. 2005]. Below, we describe studies in which PCA and related techniques such as Hierarchical Clustering Analysis (HCA) and Dynamic Network Analysis (DNA) were applied in order to gain some quasi-mechanistic insights into the response to trauma/hemorrhage (T/HS) in mice and traumatic brain injury patients, as well as the response to gram-negative bacterial endotoxin in swine.

Trauma/hemorrhagic shock (T/HS) elicits a global acute inflammatory response. We utilized multiplexing cytokine analysis coupled with data-driven modeling to gain further insights into the inflammatory response to T/HS. Mice were subjected to surgical cannulation trauma (ST) ± hemorrhagic shock (HS). Eight experimental groups were obtained, in addition to completely non-manipulated animals: a) 1, 2, 3, or 4 h ST alone and b) 1, 2, 3, or 4 h of ST + HS (25 mmHg). Serum was assayed for 20 cytokines and NO2−/NO3−. Several data-driven methods (HCA, PCA, and DNA) were used to gain insights into the global, dynamic inflammatory response that characterizes ST ± HS. HCA and PCA suggested that circulating inflammatory biomarkers in ST and ST + HS overlapped extensively despite also showing some differences, in support of prior findings [Lagoa et al. 2006]. Interestingly, DNA suggested that the responses to ST and ST + HS were extremely dynamic. The central nodes (cytokines that were the most connected to other cytokines based on statistical correlations) were shifting rapidly post-ST, from IP-10 (0–1 h),–to IP-10/IL-1β (1 – 2 h), then IL-12/NO2−/NO3− (2–3 h), and lastly TNF-α/ IL-4/IL-2/GM-CSF (3–4 h). The ST response was characterized by a high network density at all time points. In contrast, the central nodes over the same time ranges in ST + HS were MIG (0–1h), MIG/IL-6 (1–2h), MIG (2–3h), and lastly KC (3–4h); network density was zero over the first 2 h and remained lower than that of ST. These results suggest that the response to low-level ST is driven by particular cytokines in a complex and well-ordered manner, while the addition of HS, though overlapping to a large degree if one simply considers inflammation biomarkers in isolation, leads to the elaboration of distinct inflammatory mediators as part of a much less complex, disorganized response. Such insights would not have been possible from uni- or multivariate regression models, and moreover, would have been difficult to obtain strictly from the literature as part of the typical Dynamic Knowledge Representation process, since many of these cytokines and chemokines have not been assessed in prior studies of T/HS. The insights obtained from PCA and DNA could be used to guide equation- or agent-based models; we describe two examples of this type of integration below.

Bacterial sepsis, like T/HS, is also a major derangement of inflammation [Pinsky 2004; Ulloa et al. 2009]. As part of a multi-pronged, Translational Systems Biology approach to understanding sepsis [Vodovotz et al. 2004a], swine were subjected to endotoxemia as a surrogate for gram-negative bacterial sepsis, and serial plasma samples were assayed for inflammatory cytokines and NO2−/NO3−. PCA was carried out in order to discern principal drivers of inflammation in this animal model. In these experimental animals, TNF-α was produced to a high degree in all animals, and appeared to drive the early inflammatory response to endotoxin. However, PCA suggested that IL-1β rather than TNF-α may be a main driver of later inflammation. Based on this insight, a two-compartment ODE model was constructed, consisting of the lung and the blood (a surrogate for the rest of the body). A key set of interactions depicted in that model consisted of LPS inducing TNF-α in the blood, and then TNF-α entering the lung and stimulating the production of HMGB1 (a prototypical DAMP) [Klune et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2001], which in turn would stimulate the conversion of pro-IL-1β to IL-1β. Other components of this model included blood pressure, lung functional parameters such as PaO2 and FiO2, and a damage variable that recapitulates the health of the animal. This mathematical model could be easily fit to both inflammatory and physiologic data in individual endotoxemic swine that exhibited very different outcomes with regard to life and death as well as lung function (Nieman, G., Brown, D, Sarkar, J., and Vodovotz, Y, unpublished observations).

Another successful example of merging PCA with mechanistic modeling in a clinically relevant setting of acute inflammation comes from work on modeling traumatic brain injury. Traumatic brain injury induces an inflammatory cascade that drives not only the pathology of this type of trauma, but likely is also necessary for eventual healing. Given the complexity of acute inflammation and failure of nearly 30 clinical trials in traumatic brain injury, we sought to analyze cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) inflammatory cytokines for principal drivers, and to develop, calibrate, and validate patient-specific mathematical models. The CSF was chosen because it is the most proximal biofluid for traumatic brain injury, and because it is amenable to dynamic sampling; applicability and accessibility are cornerstones of Translational Systems Biology approaches [Vodovotz 2010; Vodovotz et al. 2007; Vodovotz et al. 2008]. Accordingly, multiple inflammatory cytokines were determined in serial CSF samples from 27 TBI patients, and PCA was used to determine the primary drivers of the response. Post-TBI inflammation was simulated mechanistically using ODE following a literature search to define likely mechanisms by which these biomarkers would interact in the setting of brain inflammation; this process recapitulates the Dynamic Knowledge Representation paradigm [An 2010]. The resultant mathematical model consisted of damage (a proxy for both DAMP’s as well as being a surrogate for the patient’s health status), inflammatory cells, and inflammatory cytokines. Model fitting was performed separately for individual patients, based on scaling a “trauma” parameter for relative Glasgow Coma Scale values (used clinically for stratifying traumatic brain injury patients) as well as by tuning model parameters to fit cytokine data. PCA suggested that the primary drivers of inflammation in traumatic brain injury were TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and IL-8, and accordingly 27 patient-specific ODE models were fit to these data. Ongoing studies include the generation of ensembles of models for each patient dataset, alternative models of traumatic brain injury-induced inflammation, and various parameter fitting approaches.

In summary, the studies described above suggest how data-driven modeling approaches could be integrated with existing literature to drive the generation of predictive, mechanistic computational models (Fig. 1). Such a framework could be adapted to the drug development process, as depicted in Fig. 2B. Below, we discuss another way in which dynamic computational modeling can help streamline the drug development process, namely through the simulation of clinical trials of candidate drugs.

IN SILICO CLINICAL TRIALS: A FUTURE AUGMENTED WITH SIMULATION

The ultimate test of any new drug is the randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial; this crucial step in the drug development pipeline has to date been predominantly based on empiricism, reductionism, and serendipity, and in silico methods have been suggested as a possible means by which to base these clinical trials on both mechanism of action of a given drug as well as the response of patients to a drug [Hausheer et al. 2003; Michelson et al. 2006; Vedani et al. 2006; Vodovotz and An 2009; Vodovotz et al. 2008]. Real-world clinical trials must contend with a host of practical limitations, including: relatively small cohort sizes, limited availability of measurements, finite study durations, and the presence of countless confounding factors. Numerous difficult tradeoffs must be made to balance these restrictions with the desire to collect thorough data. In contrast, trials performed in silico are not saddled with any of these constraints. In exchange for this freedom, modelers are responsible for constructing models that can realistically represent the key differences between patients and treatments that account for variability in trials. This may be done either for broad, distinct categories of patients, or on a per-patient basis. For the former, Clermont et al. [Clermont et al. 2004a] produced a very early in silico trial based on an anti-TNF-α therapy using an ODE model of systemic inflammation. That study recapitulated the general lack of efficacy of the intervention; however, the ability to “rewind the clock” in an in silico environment allowed the researchers to evaluate what would have happened if no intervention had been applied. The result was a much finer-grained assessment of which simulated patients had been helped by the intervention, which patients had actually been harmed, and which patients had been resistant to any effect of the drug. This allowed identification of potential characteristics of those patients who should be targeted for a particular intervention, i.e. “high” TNF-α producers benefitted from the anti-TNF-α therapy.

Moving from sub-group characterization and representation to its ultimate goal, personalization of a model, can be achieved by the use of customizable model parameters that alter the patient’s dynamics (e.g. co-morbidities, prior health history, relevant genetic traits, etc.) in accordance with known biology [Mi et al. 2010b]. Armed with a model that meets these criteria, virtual cohorts of arbitrary size can be generated each patient’s disease state tracked at any resolution for as long as desired. When information is available about the approximate distribution of these characteristics in real populations, this information can be used in the virtual patient generation process to ensure that the composition of sampled cohorts mirrors reality. As an example of such an approach, an agent-based model of vocal fold inflammation and healing was calibrated to the early levels of inflammatory mediators present in the laryngeal secretions of individual humans subjected to experimental phonotrauma, and could predict the later levels of these mediators in an individual-specific fashion [Li et al. 2008b]. Importantly, these individualized models were queried as to the likely efficacy of a “rehabilitative” treatment, namely resonant voice exercises, both in patients that had in fact received this treatment and in patients that did not [Li et al. 2008b]. Such models could just as well be queried with regard to the efficacy of a drug that would modulate any aspect of inflammation or healing, thereby forming the basis of a much more realistic in silico clinical trial.

In silico trials can improve clinical trial design in three major ways: 1) improved signal detection and patient sub-stratification, 2) better protocol optimization, and 3) augmented control group design. These advantages represent a progressive continuum.

The Clermont et al study [Clermont et al. 2004a] described above provides an example of the first likely benefit of in silico clinical trials: improved subgroup stratification and candidate patient identification, providing the possibility of identifying potential biomarker-defined inclusion criteria for a clinical trial. It is important to recognize that disease progression and the response to interventions are massively multifactorial, making it impossible to obtain trial cohorts that reflect the range of response that would arise in the general population. As a result, trials are very likely to miss important (positive or negative) effects in subgroups that are inadequately sampled. This can lead to later discovery of adverse events following a promising trial, or in the failure of truly useful treatments in trials that were not properly targeted to the patients that would most benefit from them. By simulating massive virtual cohorts sampled from the space of potential patients, in silico trials can achieve much more thorough sampling of possible patients. These detailed samples can reveal patient subgroups that merit particular attention, and lead to better informed patient selection criteria and more effective trials.

Protocols for modern interventions generally depend on many parameters (e.g. dosage levels, timing and frequency of administration, etc.), which must be chosen carefully. Experiments to determine these parameters over a wide range of individuals are prohibitively difficult and expensive to test; indeed, the optimal intervention strategy may well differ for each patient. Failure to choose such parameters properly can lead to failed trials, or the need for protocol revisions during a trial. In silico trials provide a cheap way to do much more rigorous computational optimization of these parameters, both on massive populations and for individual patients.

Lastly, real clinical trials must rely on control groups that are suboptimal: distinct patients who do not receive the treatment must be compared to “similar” treated patients. This definition of similarity is, of course, very crude and introduces many confounding factors into patient comparison. In silico trials, however, offer the ideal control group: each patient can be simulated with and without the intervention. Comparison of results against these “perfect” controls thus removes a source of uncertainty which is unavoidable in real trials.

Several recent studies have exploited the advantages of in silico simulation for trial design. For example, simulated trials were used to compare the potential efficacy of combinations of antibiotic treatment and vaccination in patients exposed to inhalational anthrax [Kumar et al. 2008]. We have begun to utilize mechanistic models of inflammation to help in the rational design trials of therapeutic devices, or of the devices themselves. In one study, mechanistic models of sepsis are being used for optimal patient selection and treatment protocols for testing a hemoadsorption device in sepsis patients (J. Sarkar, J. Bartels, S. Chang, Y. Vodovotz, and J.A. Kellum, unpublished observations). This class of devices is currently being tested clinically after having had a promising pre-clinical profile [Kellum 2003]. A similar class of device based on the concept of adaptive inflammation control using gene-modified cells in a bioreactor is also being developed in part using computational models of endotoxemia, sepsis, and T/HS [Vodovotz et al. 2010].

THE IN SILICO PHASE IV TRIAL: AUGMENTED ANALYSIS AND GETTING MORE OUT OF A PRIOR TRIAL

Just as virtual trial simulations can greatly improve the initial design of clinical trials, they can also serve as valuable tools for analyzing the results of prior real-world trials. In this context, the primary value of in silico modeling is to inject mechanistic understanding into the analysis process. Traditionally, trial data is analyzed with statistical methods that seek patterns in the observed patient responses. These analyses are hampered by the very limited measurements that can be collected; it is often the case that very different outcomes are reported for patients whose measurements are very similar. In silico models, however, can greatly supplement these data with predictions at missing time points and examination of completely unmeasured variables. The structure of these models imposes intrinsic constraints that tie together the many output variables of the model. When such a model is trained to reproduce the observed data for the trial, it can also make predictions for missing time points and unmeasured variables which are informed by knowledge of the trial data. In this way, the model can learn from the data and generate a limited set of hypotheses about the behaviors of latent variables, which are constrained by the biological rules built into the model. These hypotheses can be useful in two ways. First, all predictions generated by the model can themselves be subject to statistical analysis, yielding a much richer data set for discriminating between patient subgroups. Patterns may emerge in this enhanced data set that simply cannot be found solely in the sparse measured data. Second, are more importantly, these hypotheses can provide possible mechanistic explanations for the results of the trial. For example, if a drug trial shows efficacy below expectations, model predictions for latent variables constitute testable hypotheses as to how this could occur. Significantly, the biological mechanisms that have been built into the model act as an a priori filter for plausibility, and the hypotheses that are generated may identify complex underlying interactions that are not obvious to investigators. Consideration of these hypotheses may yield insights into the reasons behind a trial failure, and lead naturally to subsequent in silico trials to test potential modifications to the intervention itself, or the study design.

Lastly, training a model to trial data provides a way to test vast virtual patient cohorts, exploring how theoretical patients might have responded if they appeared in the cohort. It is important to note that the small cohort sizes of clinical trials greatly limit the ability to analyze fine-grained patient subgroups: sample sizes rapidly dwindle to the point of losing statistical significance. Training a model to reproduce the observations of a small, real cohort amounts to coupling the model’s built-in mechanisms with the specific observations of the trial. In essence, this process provides a model of the trial itself, which can be used to study unlimited numbers of additional virtual patients. In this way, much more detailed subgroup analysis is made possible simply by choosing more virtual patient samples that belong to groups of interest.

in silico trials have been used to analyze multiple real-world clinical trials in both publicly presented contexts and unpublished commercial work. For example, we trained an ODE model to data from Eli Lilly's PROWESS trial of Xigris™ for sepsis patients, and used this model to predict subgroup-level efficacy of Xigris™ for their subsequent ENHANCE trial [Chang et al. 2006]. In another example of this use of in silico clinical studies, we trained a model to a subset of data from the GenIMS study of sepsis patients [Angus et al. 2007; Kellum et al. 2007; Yende et al. 2008], and used this model to predict mortality for a reserved set of test patients [Marathe et al. 2010].

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PROSPECTS

The biocomplexity of pathophysiological processes related to systems-level diseases such as cancer, diabetes, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, sepsis and wound healing, precludes the use of traditional experimental methods for the evaluation of multi-scale causality, an essential step in the design and development of therapeutic interventions. The needs of the biomedical community and the patients it serves are such that “one-off” products based on fortuitous discovery do not provide a robust and sustainable strategy. The complexity and dimensionality (in terms of multiple factors and variables) of these biomedical issues, particularly in terms of translating mechanisms across scales of organization, essentially precludes this approach. Mere reliance on the most “advanced” methods pragmatically available, including high-throughput data generation and multi-dimensional correlative analysis, is not the answer. While correlative patterns may provide the foundational basis of causal hypothesis development, the Scientific Method mandates an additional step: experimental evaluation of causality. It is the ability to sufficiently evaluate mechanisms and causality in a multi-dimensional, high-throughput world that forms the crux of the translational dilemma. We believe that the Translational Systems Biology approach we have outlined above, which involves integrating data-driven methods with dynamic mechanistic modeling guided by and aimed at clinically-relevant outcomes, provides a basic model for the implementation of the Scientific Method in this environment and thus provides an avenue for potentially addressing the translational dilemma. In particular, we wish to emphasize that the program we have presented in the context of inflammation perfectly matches the general structure of the Scientific Method, and therefore merely provides a means by which each of the essential components of the Scientific Method can be augmented by technology.

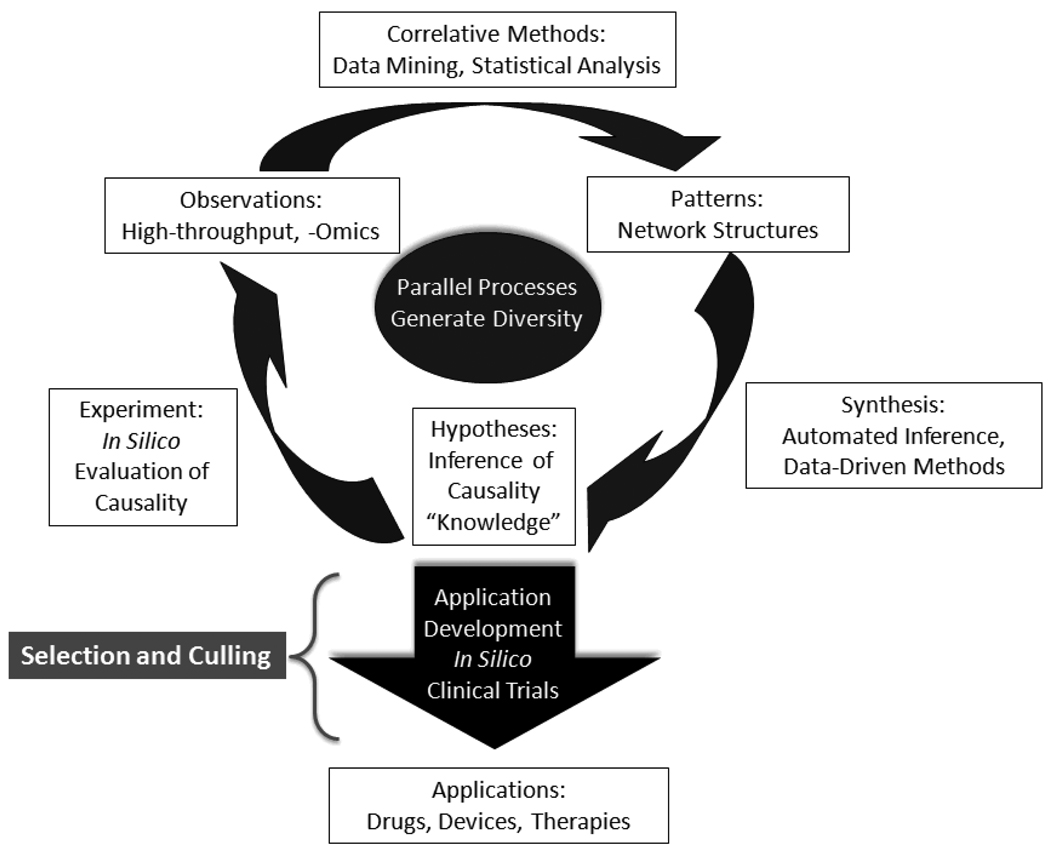

The importance of this is that Translational Systems Biology procedures provides a means of meeting the last property needed for the discovery and engineering goals of intervention development, namely diversity of solutions. Science advances through selection among plausible solutions: this is the ubiquitous evolutionary paradigm. This phenomenon is particularly true in the biosciences, where “engineering” (i.e. pharmaco-development) necessarily involves discovery. This process stands in contrast to the engineering tasks that characterize the physical sciences, where the primary goal is solution optimization given known constraints in systems whose properties are extremely well defined. Therefore, evolutionary principles must be accounted for, and exploited, if the biomedical translational dilemma is to be met [An 2010]. This process is depicted in Figure 3, where the general structure of the Scientific Method is preserved, but the movement from one process to another is characterized by increased dimensionality and throughput (as represented by the width of the connecting arrows), and the means by which to address this volume of throughput is augmented by technology. The dimensionality of throughput represents the necessary diversity in the discovery aspect of the pharmaco-development process. Selection then occurs as plausible candidates are fed into the application development arm, where in silico methods from Translational Systems Biology are used to provide the basis for selection and culling of plausible avenues of development. By matching the internal dynamic processes of the drug development pipeline with the robustness of evolutionary solution identification, we believe that Translational Systems Biology, applied at a community-level, offers a rational means of meeting the translational dilemma. This endeavor will necessarily require cross-disciplinary integration as an unprecedented level, but it is critical to recognize that in so doing we are building a process-based solution. We believe that Translational Systems Biology is a step in the direction of “engineering discovery” and enhancing the true integration of technology into the scientific process. Studies in the field of inflammation have led the way in this endeavor, and we hope that other equally complex and vexing drug targets will follow suit.

Figure 3. Discovery and development in a high-throughput world.

The traditional Scientific Cycle is challenged by the demands of very large, high-throughput/high-content data-sets, and multi-dimensional, complex systems. The technological augmentation of various steps in this cycle requires different methods and operational strategies. Data acquisition and correlative analysis have undergone significant advances in the past few decades. Now, emphasis must be placed on the technological enhancement of hypothesis testing and an engineering approach to therapy development. A data-rich, high-throughput environment calls for a similarly high-throughput approach to hypothesis evaluation and testing: a distributed, parallelized approach based on the application of Translational Systems Biology offers a potential solution. By taking advantage of the evolutionary principles of diversity and selection through culling, a parallelized implementation of the Translational Systems Biology research paradigm can provide a robust and sustainable means of meta-engineering the discovery and development process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grants R01-GM-67240, P50-GM-53789, R33-HL-089082, R01-HL080926, R01-AI080799, R01-DC-008290, and R01-HL-76157; National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research grant H133E070024; National Science Foundation 0830-370-V601 and IIS-0938393; as well as grants from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the Pittsburgh Lifesciences Greenhouse, and the Pittsburgh Tissue Engineering Initiative/Department of Defense.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DNA

Dynamic Network Analysis

- HCA: GM-CSF

granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor; Hierarchical Clustering Analysis

- IL

interleukin

- IP-10

interferon-γ-inducible protein of 10 kDa

- MIG

monokine inducible by interferon-γ, a chemokines also known as CXCL9

- NO2−/NO3−

nitrite + nitrate, reaction products of nitric oxide

- PCA

Principal Component Analysis

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Vodovotz is a co-founder of and consultant to Immunetrics, Inc., which has licensed from the University of Pittsburgh the rights to commercialize aspects of the mathematical modeling of inflammation. Dr. An is also a consultant to Immunetrics, Inc.

REFERENCES

- Alt W, Lauffenburger DA. Transient behavior of a chemotaxis system modelling certain types of tissue inflammation. J.Math.Biol. 1987;24(6):691–722. doi: 10.1007/BF00275511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alverdy J, Zaborina O, Wu L. The impact of stress and nutrition on bacterial-host interactions at the intestinal epithelial surface. Curr.Opin.Clin.Nutr.Metab Care. 2005;8(2):205–209. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200503000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An G. Agent-based computer simulation and SIRS: building a bridge between basic science and clinical trials. Shock. 2001;16(4):266–273. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An G. In-silico experiments of existing and hypothetical cytokine-directed clinical trials using agent based modeling. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2050–2060. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000139707.13729.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An G. Introduction of a agent based multi-scale modular architecture for dynamic knowledge representation of acute inflammation. Theor.Biol.Med.Model. 2008;5(11) doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An G. Dynamic Knowledge Representation using Agent Based Modeling: Ontology Instantiation and Verification of Conceptual Models. In: Maly I, editor. Systems Biology: Methods in Molecular Biology Series. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2009a. pp. 445–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An G. A model of TLR4 signaling and tolerance using a qualitative, particle event-based method: Introduction of Spatially Configured Stochastic Reaction Chambers (SCSRC) Math.Biosci. 2009b;217:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An G. Closing the scientific loop: Bridging correlation and causality in the petaflop age. Science Translational Med. 2010 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An G, Faeder JR. Detailed qualitative dynamic knowledge representation using a BioNetGen model of TLR-4 signaling and preconditioning. Math.Biosci. 2009;217:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An G, Mi Q, Dutta-Moscato J, Solovyev A, Vodovotz Y. Agent-based models in translational systems biology. WIRES. 2009;1:159–171. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An G, Vodovotz Y. Translational systems biology: Introduction of an engineering approach to the pathophysiology of the burn patient. J.Burn Care Res. 2008;29:277–285. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31816677c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus DC, Yang L, Kong L, Kellum JA, Delude RL, Tracey KJ, Weissfeld L. Circulating high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) concentrations are elevated in both uncomplicated pneumonia and pneumonia with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(4):1061–1067. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259534.68873.2A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arciero J, Rubin J, Upperman J, Vodovotz Y, Ermentrout GB. Using a mathematical model to analyze the role of probiotics and inflammation in necrotizing enterocolitis. PLoS ONE. 2010 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JE. Mathematical modeling and analysis in biochemical engineering: past accomplishments and future opportunities. Biotechnol.Prog. 1998;14(1):8–20. doi: 10.1021/bp9701269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borer JS, Simon LS. Cardiovascular and gastrointestinal effects of COX-2 inhibitors and NSAIDs: achieving a balance. Arthritis Res.Ther. 2005;7 Suppl 4:S14–S22. doi: 10.1186/ar1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornholdt S. Modeling genetic networks and their evolution: a complex dynamical systems perspective. Biol.Chem. 2001;382(9):1289–1299. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruggeman FJ, Westerhoff HV. Approaches to biosimulation of cellular processes. J.Biol Phys. 2006;32(3–4):273–288. doi: 10.1007/s10867-006-9016-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese L. The yin and yang of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. Cleve.Clin.J Med. 2006;73(3):251–256. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.73.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S, Baratt A, Clermont G, Planquois JM, Yan SB, Williams M, Macias W. Mathematical model predicting outcomes of sepsis patients treated with Xigris(R): ENHANCE trial. Shock. 2006;25:70–71. [Google Scholar]

- Chaouiya C. Petri net modelling of biological networks. Brief.Bioinform. 2007;8(4):210–219. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbm029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplain M, Anderson A. Mathematical modelling of tumour-induced angiogenesis: network growth and structure. Cancer Treat.Res. 2004;117:51–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8871-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow CC, Clermont G, Kumar R, Lagoa C, Tawadrous Z, Gallo D, Betten B, Bartels J, Constantine G, Fink MP, et al. The acute inflammatory response in diverse shock states. Shock. 2005;24:74–84. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000168526.97716.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen C, Thakar J, Albert R. Systems-level insights into cellular regulation: inferring, analysing, and modelling intracellular networks. IET.Syst.Biol. 2007;1(2):61–77. doi: 10.1049/iet-syb:20060071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clermont G, Bartels J, Kumar R, Constantine G, Vodovotz Y, Chow C. In silico design of clinical trials: a method coming of age. Crit Care Med. 2004a;32:2061–2070. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000142394.28791.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clermont G, Chow CC, Constantine GM, Vodovotz Y, Bartels J. Proceedings ofthe International Meeting of Classification Societies. New York: Springer Verlag; 2004b. Mathematical and Statistical Modeling of Acute Inflammation. Classification, Clustering, and Data Mining Applications; pp. 457–467. [Google Scholar]

- Clermont G, Vodovotz Y, Rubin J. Equation-Based Models of Dynamic Biological Systems. In: Aird WC, editor. Endothelial Biomedicine. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 1780–1785. [Google Scholar]

- Csete ME, Doyle JC. Reverse engineering of biological complexity. Science. 2002;295(5560):1664–1669. doi: 10.1126/science.1069981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daun S, Rubin J, Vodovotz Y, Roy A, Parker R, Clermont G. An ensemble of models of the acute inflammatory response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide in rats: Results from parameter space reduction. J.Theor.Biol. 2008;253:843–853. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day J, Rubin J, Vodovotz Y, Chow CC, Reynolds A, Clermont G. A reduced mathematical model of the acute inflammatory response: II. Capturing scenarios of repeated endotoxin administration. J.Theor.Biol. 2006;242:237–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearden JC. In silico prediction of ADMET properties: how far have we come? Expert.Opin.Drug Metab Toxicol. 2007;3(5):635–639. doi: 10.1517/17425255.3.5.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Foteinou PT, Calvano SE, Lowry SF, Androulakis IP. Agent-Based Modeling of Endotoxin-Induced Acute Inflammatory Response in Human Blood Leukocytes. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(2):e9249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein-Keshet L. Mathematical models in biology. New York: Random House; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ekins S, Mestres J, Testa B. In silico pharmacology for drug discovery: applications to targets and beyond. Br.J Pharmacol. 2007a;152(1):21–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekins S, Mestres J, Testa B. In silico pharmacology for drug discovery: methods for virtual ligand screening and profiling. Br.J Pharmacol. 2007b;152(1):9–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermentrout GB, Edelstein-Keshet L. Cellular automata approaches to biological modeling. J.Theor.Biol. 1993;160(1):97–133. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1993.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MC. Recent advances in immunoinformatics: application of in silico tools to drug development. Curr.Opin.Drug Discov.Devel. 2008;11(2):233–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faeder JR, Blinov ML, Goldstein B, Hlavacek WS. Rule-based modeling of biochemical networks. Complexity. 2005;10:22–41. [Google Scholar]

- Faeder JR, Hlavacek WS, Reischl I, Blinov ML, Metzger H, Redondo A, Wofsy C, Goldstein B. Investigation of early events in Fc epsilon RI-mediated signaling using a detailed mathematical model. J.Immunol. 2003;170(7):3769–3781. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foteinou PT, Calvano SE, Lowry SF, Androulakis IP. In silico simulation of corticosteroids effect on an NFkB- dependent physicochemical model of systemic inflammation. PLoS ONE. 2009a;4(3):e4706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foteinou PT, Calvano SE, Lowry SF, Androulakis IP. Modeling endotoxin-induced systemic inflammation using an indirect response approach. Math.Biosci. 2009b;217:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein B, Faeder JR, Hlavacek WS, Blinov ML, Redondo A, Wofsy C. Modeling the early signaling events mediated by FcepsilonRI. Mol.Immunol. 2002;38(16–18):1213–1219. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncharova LB, Tarakanov AO. Molecular networks of brain and immunity. Brain Res.Rev. 2007;55(1):155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm V, Revilla E, Berger U, Jeltsch F, Mooij WM, Railsback SF, Thulke HH, Weiner J, Wiegand T, DeAngelis DL. Pattern-oriented modeling of agent-based complex systems: lessons from ecology. Science. 2005;310(5750):987–991. doi: 10.1126/science.1116681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JD. Understanding biological functions through molecular networks. Cell Res. 2008;18(2):224–237. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausheer FH, Kochat H, Parker AR, Ding D, Yao S, Hamilton SE, Petluru PN, Leverett BD, Bain SH, Saxe JD. New approaches to drug discovery and development: a mechanism-based approach to pharmaceutical research and its application to BNP7787, a novel chemoprotective agent. Cancer Chemother.Pharmacol. 2003;52 Suppl 1:S3–S15. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0653-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlavacek WS, Faeder JR, Blinov ML, Posner RG, Hucka M, Fontana W. Rules for modeling signal-transduction systems. Sci STKE. 2006;2006(344):re6. doi: 10.1126/stke.3442006re6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. Rational drug discovery: what can we learn from regulatory networks? Drug Discov.Today. 2002;7(20 Suppl):S163–S169. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(02)02463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes KA, Albeck JG, Gaudet S, Sorger PK, Lauffenburger DA, Yaffe MB. A systems model of signaling identifies a molecular basis set for cytokine-induced apoptosis. Science. 2005;310(5754):1646–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1116598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes KA, Yaffe MB. Data-driven modelling of signal-transduction networks. Nat.Rev.Mol.Cell Biol. 2006;7(11):820–828. doi: 10.1038/nrm2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenwitheesuk E, Horst JA, Rivas KL, Van Voorhis WC, Samudrala R. Novel paradigms for drug discovery: computational multitarget screening. Trends Pharmacol.Sci. 2008;29(2):62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellum JA. Hemoadsorption therapy for sepsis syndromes. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(1):323–324. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301000-00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellum JA, Kong L, Fink MP, Weissfeld LA, Yealy DM, Pinsky MR, Fine J, Krichevsky A, Delude RL, Angus DC. Understanding the inflammatory cytokine response in pneumonia and sepsis: results of the Genetic and Inflammatory Markers of Sepsis (GenIMS) Study. Arch.Intern.Med. 2007;167(15):1655–1663. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakar PS. Two-dimensional (2D) in silico models for absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity (ADME/T) in drug discovery. Curr.Top.Med.Chem. 2010;10(1):116–126. doi: 10.2174/156802610790232224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchmair J, Distinto S, Schuster D, Spitzer G, Langer T, Wolber G. Enhancing drug discovery through in silico screening: strategies to increase true positives retrieval rates. Curr.Med.Chem. 2008;15(20):2040–2053. doi: 10.2174/092986708785132843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitano H. Systems biology: a brief overview. Science. 2002;295(5560):1662–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.1069492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klune JR, Dhupar R, Cardinal J, Billiar TR, Tsung A. HMGB1: endogenous danger signaling. Mol.Med. 2008;14(7–8):476–484. doi: 10.2119/2008-00034.Klune. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Chow CC, Bartels J, Clermont G, Vodovotz Y. A mathematical simulation of the inflammatory response to anthrax infection. Shock. 2008;29:104–111. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318067da56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Clermont G, Vodovotz Y, Chow CC. The dynamics of acute inflammation. J.Theoretical Biol. 2004;230:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagoa CE, Bartels J, Baratt A, Tseng G, Clermont G, Fink MP, Billiar TR, Vodovotz Y. The role of initial trauma in the host's response to injury and hemorrhage: Insights from a comparison of mathematical simulations and hepatic transcriptomic analysis. Shock. 2006;26:592–600. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000232272.03602.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengeler JW. Metabolic networks: a signal-oriented approach to cellular models. Biol.Chem. 2000;381(9–10):911–920. doi: 10.1515/BC.2000.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Xuan J, Wang Y, Zhan M. Inferring regulatory networks. Front Biosci. 2008a;13:263–275. doi: 10.2741/2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li NYK, Verdolini K, Clermont G, Mi Q, Hebda PA, Vodovotz Y. A patient-specific in silico model of inflammation and healing tested in acute vocal fold injury. PLoS ONE. 2008b;3:e2789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao G, Zhang X, Clark DJ, Peltz G. A genomic "roadmap" to "better" drugs. Drug Metab Rev. 2008;40(2):225–239. doi: 10.1080/03602530801952815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal S, Moudgil M, Mandal SK. Rational drug design. Eur.J.Pharmacol. 2009;625(1–3):90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marathe DD, Sarkar J, Hurst KW, Inglis AM, Kellum JA, Angus DC, Vodovotz Y, Chang S. Modeling of severe sepsis patients with community acquired pneumonia (CAP) Shock. 2010;33 Supplement 1:72–73. [Google Scholar]

- Matzinger P. The danger model: a renewed sense of self. Science. 2002;296(5566):301–305. doi: 10.1126/science.1071059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):428–435. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlot C. In silico methods for early toxicity assessment. Curr.Opin.Drug Discov.Devel. 2008;11(1):80–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi Q, Li NYK, Ziraldo C, Ghuma A, Mikheev M, Squires R, Okonkwo DO, Verdolini Abbott K, Constantine G, An G. Translational systems biology of inflammation: Potential applications to personalized medicine. Personalized Medicine. 2010a doi: 10.2217/pme.10.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi Q, Li NYK, Ziraldo C, Ghuma A, Mikheev M, Squires R, Okonkwo DO, Verdolini Abbott K, Constantine G, An G, et al. Translational systems biology of inflammation: Potential applications to personalized medicine. Personalized Medicine. 2010b doi: 10.2217/pme.10.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi Q, RiviŠre B, Clermont G, Steed DL, Vodovotz Y. Agent-based model of inflammation and wound healing: insights into diabetic foot ulcer pathology and the role of transforming growth factor-á1. Wound Rep.Reg. 2007;15:617–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson S, Sehgal A, Friedrich C. In silico prediction of clinical efficacy. Curr.Opin.Biotechnol. 2006;17(6):666–670. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague G, Morris J. Neural-network contributions in biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 1994;12(8):312–324. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(94)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musante CJ, Lewis AK, Hall K. Small- and large-scale biosimulation applied to drug discovery and development. Drug Discov.Today. 2002;7(20 Suppl):S192–S196. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(02)02442-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C. Points of control in inflammation. Nature. 2002;420(6917):846–852. doi: 10.1038/nature01320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves SR, Iyengar R. Modeling of signaling networks. Bioessays. 2002;24(12):1110–1117. doi: 10.1002/bies.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen UB, Schoeberl B. Using computational modeling to drive the development of targeted therapeutics. IDrugs. 2005;8(10):822–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforova VJ, Willmitzer L. Network visualization and network analysis. EXS. 2007;97:245–275. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7643-7439-6_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo JA, Wolfe MM. Clinical potential of cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors. BioDrugs. 2001;15(9):563–572. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200115090-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli I, Timmers LF, Caceres RA, Soares MB, de Azevedo WFJ. In silico and in vitro: identifying new drugs. Curr.Drug Targets. 2008;9(12):1054–1061. doi: 10.2174/138945008786949397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky MR. Dysregulation of the immune response in severe sepsis. Am.J Med.Sci. 2004;328(4):220–229. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200410000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince JM, Levy RM, Bartels J, Baratt A, Kane JM, III, Lagoa C, Rubin J, Day J, Wei J, Fink MP, et al. In silico and in vivo approach to elucidate the inflammatory complexity of CD14-deficient mice. Mol.Med. 2006;12:88–96. doi: 10.2119/2006-00012.Prince. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A, Rubin J, Clermont G, Day J, Vodovotz Y, Ermentrout GB. A reduced mathematical model of the acute inflammatory response: I. Derivation of model and analysis of anti-inflammation. J.Theor.Biol. 2006;242:220–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho S, You S, Kim Y, Hwang D. From proteomics toward systems biology: integration of different types of proteomics data into network models. BMB.Rep. 2008;41(3):184–193. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2008.41.3.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RiviŠre B, Epshteyn Y, Swigon D, Vodovotz Y. A simple mathematical model of signaling resulting from the binding of lipopolysaccharide with Toll-like receptor 4 demonstrates inherent preconditioning behavior. Math.Biosci. 2009;217:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg AL. Recent innovations in intensive care unit risk-prediction models. Curr.Opin.Crit Care. 2002;8(4):321–330. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200208000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovira X, Pin JP, Giraldo J. The asymmetric/symmetric activation of GPCR dimers as a possible mechanistic rationale for multiple signalling pathways. Trends Pharmacol.Sci. 2010;31(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rychly DJ, DiPiro JT. Infections associated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25(9):1181–1192. doi: 10.1592/phco.2005.25.9.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanga S, Sinek JP, Frieboes HB, Ferrari M, Fruehauf JP, Cristini V. Mathematical modeling of cancer progression and response to chemotherapy. Expert Rev.Anticancer Ther. 2006;6(10):1361–1376. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.10.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos CC, Zhang H, Liu M, Slutsky AS. Bench-to-bedside review: Biotrauma and modulation of the innate immune response. Crit Care. 2005;9(3):280–286. doi: 10.1186/cc3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlag G, Redl H. Mediators of injury and inflammation. World J Surg. 1996;20(4):406–410. doi: 10.1007/s002689900064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solovyev A, Mikheev M, Zhou L, Dutta-Moscato J, Ziraldo C, An G, Vodovotz Y, Mi Q. SPARK: A framework for multi-scale agent-based biomedical modeling. Int.J.Agent Technologies and Systems. 2010 doi: 10.4018/jats.2010070102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoiser B, Knapp S, Thalhammer F, Locker GJ, Kofler J, Hollenstein U, Staudinger T, Wilfing A, Frass M, Burgmann H. Time course of immunological markers in patients with the systemic inflammatory response syndrome: evaluation of sCD14, sVCAM-1, sELAM-1, MIP-1 alpha and TGF-beta 2. Eur J Clin Invest. 1998;28(8):672–678. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1998.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stransky B, Barrera J, Ohno-Machado L, De Souza SJ. Modeling cancer: integration of "omics" information in dynamic systems. J Bioinform.Comput.Biol. 2007;5(4):977–986. doi: 10.1142/s0219720007002990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekirian TL, Thomas SN, Yang A. Advancing signaling networks through proteomics. Expert.Rev.Proteomics. 2007;4(4):573–583. doi: 10.1586/14789450.4.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres A, Bentley T, Bartels J, Sarkar J, Barclay D, Namas R, Constantine G, Zamora R, Puyana JC, Vodovotz Y. Mathematical modeling of post-hemorrhage inflammation in mice: Studies using a novel, computer-controlled, closed-loop hemorrhage apparatus. Shock. 2009;32:172–178. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318193cc2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa L, Brunner M, Ramos L, Deitch EA. Scientific and clinical challenges in sepsis. Curr.Pharm.Des. 2009;15(16):1918–1935. doi: 10.2174/138161209788453248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Waterbeemd H. Improving compound quality through in vitro and in silico physicochemical profiling. Chem.Biodivers. 2009;6(11):1760–1766. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200900056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz RJ, Zamora I, Li Y, Reiling S, Shen J, Cruciani G. The challenges of in silico contributions to drug metabolism in lead optimization. Expert.Opin.Drug Metab Toxicol. 2010;6(7):851–861. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2010.499123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedani A, Dobler M, Lill MA. The challenge of predicting drug toxicity in silico. Basic Clin.Pharmacol.Toxicol. 2006;99(3):195–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JL, Ferreira F, Moreno R. Scoring systems for assessing organ dysfunction and survival. Crit Care Clin. 2000;16(2):353–366. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovotz Y. Translational systems biology of inflammation and healing. Wound.Repair Regen. 2010;18(1):3–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovotz Y, An G. Systems Biology and Inflammation. In: Yan Q, editor. Systems Biology in Drug Discovery and Development: Methods and Protocols. Totowa, NJ: Springer Science & Business Media; 2009. In Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vodovotz Y, Chow CC, Bartels J, Lagoa C, Prince J, Levy R, Kumar R, Day J, Rubin J, Constantine G, et al. In silico models of acute inflammation in animals. Shock. 2006;26:235–244. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000225413.13866.fo. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovotz Y, Clermont G, Chow C, An G. Mathematical models of the acute inflammatory response. Curr.Opin.Crit Care. 2004a;10(5):383–390. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000139360.30327.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovotz Y, Clermont G, Chow C, An G. Mathematical models of the acute inflammatory response. Curr.Opin.Crit Care. 2004b;10:383–390. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000139360.30327.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovotz Y, Clermont G, Hunt CA, Lefering R, Bartels J, Seydel R, Hotchkiss J, Ta'asan S, Neugebauer E, An G. Evidence-based modeling of critical illness: An initial consensus from the Society for Complexity in Acute Illness. J.Crit Care. 2007;22:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovotz Y, Constantine G, Faeder J, Mi Q, Rubin J, Sarkar J, Squires R, Okonkwo DO, Gerlach J, Zamora R, et al. Translational systems approaches to the biology of inflammation and healing. Immunopharmacol.Immunotoxicol. 2010;32:181–195. doi: 10.3109/08923970903369867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovotz Y, Constantine G, Rubin J, Csete M, Voit EO, An G. Mechanistic simulations of inflammation: Current state and future prospects. Math.Biosci. 2009;217:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovotz Y, Csete M, Bartels J, Chang S, An G. Translational systems biology of inflammation. PLoS.Comput.Biol. 2008;4:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogels TP, Rajan K, Abbott LF. Neural network dynamics. Annu.Rev.Neurosci. 2005;28:357–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E, Lenferink A, O'Connor-McCourt M. Cancer systems biology: exploring cancer-associated genes on cellular networks. Cell Mol.Life Sci. 2007;64(14):1752–1762. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7054-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Yang H, Czura CJ, Sama AE, Tracey KJ. HMGB1 as a late mediator of lethal systemic inflammation. Am.J.Respir.Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10 Pt 1):1768–1773. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2106117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen B, Fitch WL. Analytical strategies for the screening and evaluation of chemically reactive drug metabolites. Expert Opin.Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5(1):39–55. doi: 10.1517/17425250802665706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart DS. Bioinformatics in drug development and assessment. Drug Metab Rev. 2005;37(2):279–310. doi: 10.1081/dmr-55225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]