Abstract

Objective

We compared two active cooling devices to passive cooling in a moderate (≈22°C) temperature environment on heart rate (HR) and core temperature (Tc) recovery when applied to firefighters following 20 min. of fire suppression.

Methods

Firefighters (23 male, 2 female) performed 20 minutes of fire suppression at a live fire evolution. Immediately following the evolution, the subjects removed their thermal protective clothing and were randomized to receive forearm immersion (FI), ice water perfused cooling vest (CV) or passive (P) cooling in an air-conditioned medical trailer for 30 minutes. Heart rate and deep gastric temperature were monitored every five minutes during recovery.

Results

A single 20-minute bout of fire suppression resulted in near maximal HR (175±13 - P, 172±20 - FI, 177±12 beats•min−1 - CV) when compared to baseline (p < 0.001), a rapid and substantial rise in Tc (38.2±0.7 - P, 38.3±0.4 - FI, 38.3±0.3° - CV) compared to baseline (p < 0.001), and mass lost from sweating of nearly one kilogram. Cooling rates (°C/min) differed (p = 0.036) by device with FI (0.05±0.04) providing higher rates than P (0.03±0.02) or CV (0.03±0.04) although differences over 30 minutes were small and recovery of body temperature was incomplete in all groups.

Conclusions

During 30 min. of recovery following a 20-minute bout of fire suppression in a training academy setting, there is a slightly higher cooling rate for FI and no apparent benefit to CV when compared to P cooling in a moderate temperature environment.

Keywords: Heat stress, hyperthermia, thermoregulation, firefighter

INTRODUCTION

Work in a hot environment, experienced during fire suppression, results in activation of heat loss mechanisms without changing the hypothalamic set point for Tc [1]. The typical human response to rising Tc is to convectively move excess heat from the core to the periphery by increasing skin blood flow. The rising skin temperature is subsequently accompanied by sweating releasing heat to the environment by evaporation.

Structural fire suppression encompasses multiple functions including fire extinguishment, victim rescue, ventilation of smoke, and post-fire overhaul that require heavy physical exertion [2, 3]. Firefighters must use thermal protective clothing (TPC) during these fire suppression activities to protect them from extreme environmental heat, trauma, and burn injuries [4]. However, these garments inhibit normal thermoregulation resulting in cardiovascular and thermal strain [4]. Although skin blood flow is increased and sweating commences during work in TPC, evaporation is largely eliminated leading to a progressive increase in Tc and HR and a decrease in plasma volume. The resultant heat and cardiovascular stress limits work capacity and may cause injury to the firefighter.

To improve safety at a fire scene following exertion in TPC, structured rehabilitation periods including heat stress remediation are mandated by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Standard 1584 [5]. However, there are few specific recommendations for cooling found within that guideline.

There have been multiple studies of active and passive cooling for exercise induced hyperthermia in both athletes and firefighters [6–9]. Multiple devices including cooling vests, hand and forearm immersion in cold water, and misting fans have been investigated after subjects exercised while wearing TPC in a controlled laboratory setting or non-fire field settings [8–12].

A previous laboratory study of firefighters working in TPC has shown that active cooling by forearm and hand immersion improved heart rate (HR) and body core temperature (Tc) recovery during structured breaks and extended work time in a hot, humid environment when compared to passive cooling and misting fans [9]. However, these findings have not been verified in the field nor has an active cooling modality been compared to passive cooling in a controlled, moderate temperature and humidity environment, such as could be created in an air-conditioned vehicle. The objective of the present study was to compare the effect of a liquid perfused cooling vest (CV), forearm immersion (FI), and passive cooling in a moderate temperature environment (P) on HR and Tc recovery following 20 minutes of structural fire suppression activity.

METHODS

The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved this study. Subjects provided written informed consent prior to participation. Subjects consisted of 25 firefighters (23 males, 2 females) who were apparently healthy adults age 32.1 ± 7.6 years (Table 1). Subjects were recruited from both career and volunteer fire departments in response to a regional advertisement and were certified to the Pennsylvania Essentials of Firefighting with Live Burn or the NFPA 1001 Standard for Professional Firefighter Qualifications Firefighter I or Firefighter II [13].

Table 1.

Subject Demographics

| Passive (N = 9) | Forearm Immersion (N = 13) | Cooling Vest (N = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.2 ± 8.9 | 32.2 ± 7.2 | 30.6 ± 6.4 |

| Height (cm) | 174.4 ± 5.7 | 175.2 ± 7.3 | 176.9 ± 6.5 |

| Weight (kg) | 89.3 ± 22.4 | 86.6 ± 15.6 | 95.7 ± 22.2 |

| VO2peak (mg/kg per min) | 43.3 ± 8.9 | 43.3 ± 9.0 | 40.4 ± 8.1 |

| Body Fat (%) | 18.4 ± 7.2 | 14.9 ± 3.9 | 17.6 ± 6.8 |

Values presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Preliminary Testing

Subjects received a physical exam from a study physician including a 12-lead ECG and maximal exercise test prior to the fire evolution. Height and weight were determined using a Healthometer Digital Scale and stadiometer. Body fat was determined by three skinfold measurements [14]. Exclusion criteria included known cardiac or respiratory disease, use of medications known to alter HR response or thermoregulation, and previous abdominal surgery. No subject was excluded after screening.

Subjects completed a Bruce protocol treadmill test during the screening visit to determine aerobic capacity (VO2max). Open circuit spirometry (Parvomedics TrueOne 2400, Sandy UT) was used to measure respiratory rate (RR), volume of expired air (VESTPD), oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2). A 12-lead ECG and blood pressure (BP) was obtained at rest and every three minutes during the protocol, immediately post exercise, and every five minutes during recovery for 15 minutes to screen for undiagnosed ischemic response to exercise. Stress test results were interpreted by a cardiologist. Female subjects were screened for pregnancy prior to the treadmill test and live fire evolutions.

Testing Session

Live fire evolutions took place on two consecutive days in July 2009 at the Allegheny County Fire Academy between 0900 and 1500 hrs. Nine of 25 subjects participated on both days. These subjects used a different cooling device on each day. Subjects were asked to refrain from caffeine, alcohol, and exercise for 12 hours prior to participation. Subjects were asked to eat their normal breakfast on the day of the fire evolution and were provided an indigestible pill to monitor Tc (HQ Inc, Palmetto FL). Subjects were instructed to take the capsule eight hours prior to arrival. After arriving, the subjects voided, had urine specific gravity checked to confirm euhydration (USG < 1.020), were weighed nude, and were fitted with a Polar HR monitor (Woodbury NY).

Following instrumentation, subjects participated in a NFPA 1403 compliant live fire evolution supervised by Fire Academy instructors [15]. The training evolution lasted approximately 20 minutes and required subjects, in teams of four, to advance a 4.4 cm charged hose line to the second floor of a concrete structure to extinguish and ventilate a simulated bedroom fire. Subjects rotated position on the hose line and advanced to the next room to repeat the process. Instructors reignited the extinguished rooms to allow continuous extinguishment and ventilation until 20 minutes had elapsed. Subjects then withdrew from the structure where exit HR and Tc were assessed. Subjects then received an assignment to a cooling strategy.

Firefighters wore standard uniform pants and long sleeve t-shirt. Each firefighter brought their own TPC ensemble consisting of heavy coat, trousers, gloves, steel toed boots, polycarbonate helmet, Nomex hood, and self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA). All TPC was inspected by Fire Academy instructors on the day of the fire evolution to ensure compliance with NFPA 1971 standards [16].

After completing the fire suppression activities, participants were randomized to one of the following three cooling groups for rehabilitation: forearm and hand immersion in cool water using a specially designed folding chair (FI) (N = 11), (Kore Kooler™, Morning Pride, Dayton OH), a liquid perfused cooling vest (CV) (N = 13) (Cool Shirt® Personal Cooling System, Shafer Enterprises, Inc., Stockbridge GA), or passive cooling in an air-conditioned (22.2 ± 0.6°C) medical trailer (P) (N = 9). The rehabilitation period lasted 30 minutes during which all subjects consumed exactly 500 ml of room temperature water. Subjects randomized to FI or CV were seated in a shaded, open-air pavilion (22.5 ± 2.9°C, relative humidity 47.2 ± 11.0%). The cooling vest was applied following manufacture's instructions using ice water in the reservoir and wetting the vest in ice water prior to use. The forearm immersion chair reservoirs were filled with water (20.9 ± 0.4°C) collected from a fire hose before each subject use.

After randomization, subjects doffed SCBA, helmet, gloves, coat, and Nomex hood and opened the front of the TPC trousers. Subjects were seated during the intervention and data collection. During the 30-minute post-fire monitoring period Tc, and HR were recorded every five minutes. Oral temperature (SureTemp 690, Welch Allyn, Skaneateles Falls NY) was recorded at the beginning and end of the 30-minute period.

Following data collection, subjects were weighed nude prior to voiding. Body mass was corrected for the oral intake of water to provide an estimate of body water lost from sweating.

Statistical Analysis

Data were entered from paper recording forms into a spreadsheet, verified for accuracy, and imported into SPSS for Mac v11 (SPSS Inc, Chicago IL) and SAS version 9.2 for analyses. All subject demographic and morphometric measurements were continuous and are presented as mean ± SD. Heart rate, Tc, and change in body mass measured pre/post fire suppression were compared by two-way ANOVA conditioned on time and cooling strategy. HR and Tc were measured on each individual after fire suppression every five minutes from 0 to 30 minutes. We used a repeated measures marginal model assuming a normal distribution with first-order autoregressive covariance structures for both HR and Tc. We first tested for group differences in the linear and curvature changes over time (α=0.05 for each interaction). If the interaction was not significant, we dropped the term from the model and tested the next highest ordered term. Predicted equations from the final models for HR recovery and cooling rate are presented for each group over time. Oral and core temperatures at the beginning and end of the rehab period were examined with a Pearson Correlation Coefficient and Bland-Altman Test of Agreement. All statistical tests were two sided and conducted at α=0.05.

A post hoc analysis was performed for Tc and HR using commonly applied physiological cut-offs to determine if a firefighter may return to the incident. Survival analysis stratified by cooling device was performed for the criteria 1) HR < 100 beats•min−1, 2) HR < 80 beats•min−1, and 3) 50% recovery of the rise in Tc during fire suppression. In exploratory analyses, HR recovery was also stratified by firefighter VO2max using cutoffs previously identified for the fire service (1: low fit, below 42 (N=15), 2: moderately fit, 42–48 (N=8), and 3: high fit, above 48 mL•kg−1•min−1 (N=9)) [2].

RESULTS

Physiologic measures after fire suppression

As expected, twenty minutes of fire suppression activities results in significant cardiovascular and thermal stress. Heart rate approached age predicted maximum values (p < 0.001) while Tc increased approximately 0.7°C in all groups (p < 0.001) (Table 2). Participants in the three groups had similar HR, Tc, and changes in these measures after fire suppression activities. Subjects lost 0.84 ± 0.34 (P), 0.72 ± 0.41 (FI), 0.86 ± 0.36 (CV) kg of mass following fire suppression.

Table 2.

Physiologic measures before and immediately following 20 minutes of fire suppression

| Heart Rate (bpm) | Core Temperature (°C) | Change in Body Mass (kg) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||

| Passive | 121 ± 29 | 175 ± 13 | 37.5 ± 0.5 | 38.2 ± 0.7 | −0.84 ± 0.34 |

| Forearm Immersion | 108 ± 23 | 172 ± 20 | 37.4 ± 0.3 | 38.3 ± 0.4 | −0.72 ± 0.41 |

| Cooling Vest | 116 ± 22 | 177 ± 12 | 37.6 ± 0.2 | 38.3 ± 0.3 | −0.86 ± 0.36 |

Values presented as mean ± standard deviation. bpm = beats per minute. Heart rate and Tc increased following 20 minutes of fire suppression in all groups (p < 0.001). No differences were identified between groups in post HR, Tc, or change in body mass.

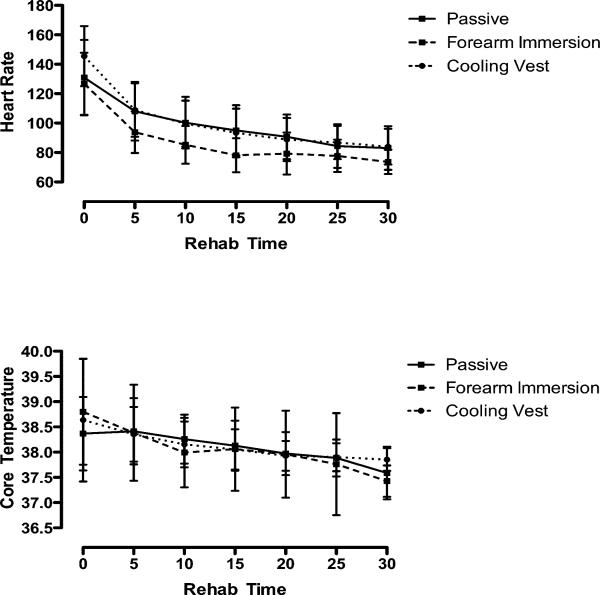

Physiologic measures during recovery

Heart rate decreased over time during the recovery period (linear slope, p < 0.001) with a leveling off after 20 minutes (time2 p<0.0001) (Figure 1). Heart rate recovery did not differ among groups (difference in slopes test, p = 0.85).

Figure 1.

Heart rate and Tc recovery during a 30-minute rehab period following fire suppression for passive (solid line), forearm immersion (dashed line) and liquid perfused vest (dotted line) cooling.

The predicted equations for the HR recovery by device are VEST: Predicted heart rate = 139.07 − 4.543 * Minute + 0.091 * Minute2, CHAIR: Predicted heart rate = 127.90 − 4.543 * Minute + 0.091 * Minute2, PASSIVE: Predicted heart rate = 132.68 − 4.543 * Minute + 0.091 * Minute2

The predicted equations for the Tc by device are VEST: Predicted Tc = 38.463 − 0.023 * Minute, CHAIR: Predicted Tc = 38.804 − 0.048 * Minute, PASSIVE: Predicted Tc = 38.427 − 0.021 * Minute.

Cooling rates (°C•min−1) were 0.03±0.02 (P), 0.05±0.04 (FI), and 0.03±0.04 CV and differed by group (p=0.036) with the FI demonstrating a greater cooling rate over time (Figure 1).

Oral temperature at the start and end of the rehab was correlated with Tc (R2 = 0.31, p < 0.001). However, a Bland-Altman analysis revealed that agreement was poor with a mean bias of −1.3°C (95%CI −2.7, 0.05) indicating that oral temperature collected in the field does not accurately predict Tc.

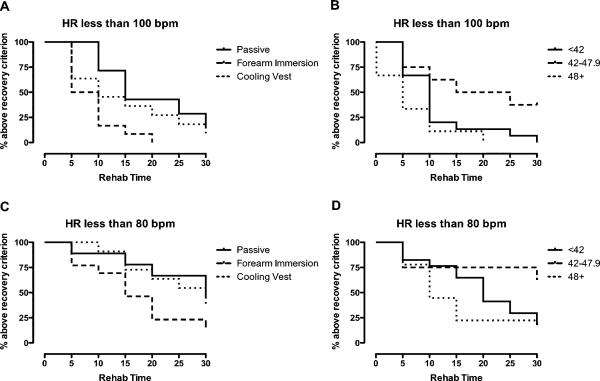

Survival Analysis of HR and Tc recovery

Survival analysis of HR recovery was conditioned on the commonly accepted criterion of HR less than 100 beats•min−1 before returning to fire suppression activities and a more conservative criterion of HR less than 80 beats•min−1. When examined by cooling device, the survival curves did not differ between groups (Figure 2A, 2C). A substantial proportion of subjects in all groups failed to reach the recovery criterion of less than 80 beats•min−1 during a 30-minute rest interval following fire suppression. Two subjects (1, P; 1 CV) failed to reach the recovery criterion of less than 100 beats•min−1 during a 30-minute rest interval following fire suppression. These exploratory analyses were repeated dividing subjects by aerobic capacity into three groups using previously published guidelines for firefighter fitness of 42.0 and 48.0 mL•kg−1•min−1 VO2max (Figure 2B, 2D) (9). When examined by fitness, the moderately fit group achieved HR < 100 beats•min−1 more slowly than both the low and high fit groups (p = 0.03). This difference was not observed for the HR < 80 bpm criterion.

Figure 2.

Survival analysis of HR recovery during a 30-minute rehab period following fire suppression for the criterion of HR < 100 and HR < 80 stratified by cooling device (Panels A, C) and subjects aerobic fitness (Panels B, D).

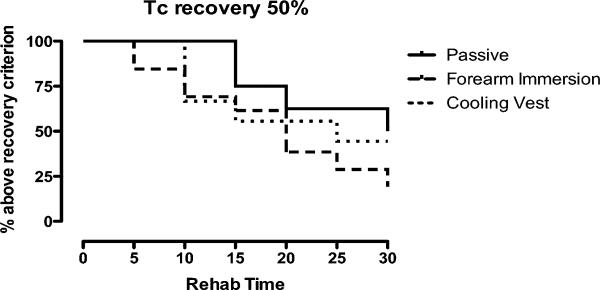

Survival analyses of Tc were performed using the relative criterion of 50% recovery of the rise observed during fire suppression (Figure 3). No differences were identified between cooling strategies.

Figure 3.

Survival analysis of Tc recovery during a 30-minute rehab period following fire suppression stratified by cooling device.

DISCUSSION

This study compared two common active cooling modalities to passive cooling in moderate temperature and humidity environment following 20 minutes of fire suppression. Our study is similar to previous studies of fire suppression in that we observed a significant hyperthermia, tachycardia, and hypohydration [17, 18]. Although the forearm immersion group had a more rapid cooling rate, recovery was incomplete in all groups when firefighters were provided an operationally relevant interval of 30 minutes for fireground rehabilitation.

Our study augments what is currently known about cooling firefighters during fireground rehabilitation by examining firefighter cooling in moderate ambient temperature (≈22°C). Three previous studies examining recovery in a hot environment have reported that it is difficult to mitigate heat stress without active cooling devices such as fans, vests, or forearm immersion [9, 10, 19]. However, across much of North America and Europe, extremely hot (≥35°C) ambient temperatures are rare. In a previous study of active and passive cooling, conducted in our lab, we failed to identify an advantage of active cooling during a 20-minute recovery period after 50 minutes of treadmill walking in TPC in a heated room [8]. In that laboratory study, the cooling rates for all modalities averaged 0.05°C•min−1 which is similar to what we have reported in the FI group in the present field study. We believe these small differences in P and CV cooling rates between the laboratory and the field can be attributed to the garments worn during the recovery period. In the laboratory study, subjects recovered in long uniform pants and a short sleeve cotton shirt without wearing TPC. In this field study, subjects recovered in TPC pants (a common field practice) and a long sleeve cotton shirt (a fire academy requirement). Long sleeve shirts are not normally worn in the summer months outside of the training academy and TPC could be pushed down below the knees while the firefighter is seated for recovery, which may negate the small advantage seen in the FI group.

Another study comparing hand cooling in cold tap water failed to result in differences in Tc and HR recovery when compared to the control condition of seated recovery in a cooler 15°C room after removing the helmet, coat and hood [11]. Collectively, these studies indicate that the addition of cooling devices does not allow for full recovery of HR and Tc in an operationally relevant time interval when the majority of thermal protective clothing is removed and subjects rest in a moderate temperature and humidity environment. Furthermore, our data show that an air-conditioned vehicle may be used in a field setting to create this advantageous environment when the temperature and/or humidity are suboptimal.

Our study contrasts with a study of multimodal cooling (forearm immersion combined with a cooling vest) in a 21°C room after 20 minutes of treadmill walking where passive cooling was found to be inferior to active cooling [20]. However, in that laboratory study, the recovery period was limited to 15 minutes and appears to include the time required for doffing and donning TPC for a second bout of treadmill walking. We note that the cooling rate for the active cooling arm in is comparable to the passive cooling group in the present report (0.03 ± 0.02°C/min vs. 0.02 ± 0.01°C/min) [20]. The passive cooling rate of −0.01 ± 0.01°C/min reported in that study [20] is likely influenced by the short period of continued heat accumulation following cessation of exercise in protective clothing that has been reported in other studies [8, 18, 21]. Although the multimodal technique of CV and FI takes advantage of a larger surface area for cooling and may be advantageous for short recovery periods, we hypothesize greater Tc reduction would have been noted in the passive cooling group in Barr et al if the recovery period had been lengthened beyond 15 minutes.

It is important to note that even after 30 minutes of structured recovery that included cooling and rehydration, most subjects remained mildly hyperthermic with seated HR exceeding 80 bpm. It may not be possible to return a firefighter to baseline or near-baseline status within a 20–30 minute recovery period after significant exertion in TPC using current cooling strategies. Prolonged fireground operations may need to be facilitated by increasing the number of personnel available for operations to allow for longer or more frequent recovery periods. It may also be necessary to investigate additional cooling devices and work practices to prevent or attenuate heat stress during fire suppression activities.

Although not powered for this purpose, the exploratory survival analysis of HR and Tc recovery is provocative and requires further investigation. Survival analysis was used to describe the proportion of the cohort not achieving a desired level of physiologic recovery in the allotted 30-minute rehab period. No differences in several commonly used criteria for HR or Tc recovery were seen between devices. This strengthens the observation that creating a cool, low humidity environment that favors thermoregulation is as effective as applying a cooling device.

However, differences in HR recovery were noted when stratified by fitness. A previous study of fire suppression skills found that the most demanding operations required a VO2 of at least 42 mL•kg−1•min−1 [2]. While this criterion is often used as a minimum standard for firefighter fitness, sustaining those activities for an operationally relevant interval of 10 minutes requires a VO2max of approximately 48 mL•kg−1•min−1. When stratifying subjects by VO2max we observed slower HR recovery in the middle fit (42–48 mL•kg−1•min−1) group when compared to the low and high fit groups. The difference between the middle and high fit groups is consistent with previous studies showing faster reestablishment of cardiac vagal tone and greater HR recovery immediately following exercise [22, 23]. The lack of difference between the low and high fit groups is more difficult to reconcile. We speculate that the low fit individuals either self-paced during the fire suppression activities, working at a lower percentage of their individual VO2max and relying more heavily on their partners, or were simply unable to achieve higher HR. Since we were not able to record HR during fire suppression we cannot verify this in the present report. However, if these observations are confirmed in a larger cohort, it may indicate that employing the 42 mL•kg−1•min−1 minimum for firefighter fitness leads to the deployment of firefighters who will have difficulty recovering for subsequent bouts of work, especially if those subsequent work periods require heavy exertion such as victim rescue [3]. Furthermore, validation of these observations may require reconsideration of how individuals are monitored and the decision making process to return them to fire suppression activities.

Our subjects performed fire suppression and ventilation. However, this was a training fire in a controlled setting. Physiologic responses in the uncertain and rapidly changing environment of an actual fire may differ. Nevertheless, our protocol produced near maximal HR, a rapid and substantial rise in Tc, and nearly one liter of mass lost to sweating in an operationally relevant time interval. Furthermore, our subject pool was diverse representing both the career and volunteer fire service and displayed a wide range of fitness and morphometrics but they may not be representative of firefighters in other areas of North America and Europe.

We compared an air-conditioned environment to two popular cooling devices on a typical early-summer day in Western Pennsylvania (approximately 24°C). We cannot address the effectiveness of other devices. However, given that the currently marketed devices employ a common and limited set of conductive or convective cooling strategies, we believe that it is unlikely that dramatically different results would be obtained with another cooling device applied after fire suppression. Finally, while these data suggest there is a limited role for active cooling of firefighters when moderate temperature environment and low humidity conditions favor passive cooling, we cannot speak to their use in environmental conditions other than those presently employed in this study and in studies of recovery in hot, humid conditions [9].

In conclusion, a single 20-minute bout of fire suppression in a training academy setting results in near maximal HR, a rapid and substantial rise in Tc, and mass lost from sweating of nearly one kilogram. Although the cooling rate (°C•min−1) was slightly higher in the FI group, removing TPC in a moderate temperature environment (approximately 22°C) after fire suppression results in 30-minute HR and Tc recovery that is similar to the recovery realized with forearm immersion or ice water-perfused cooling vests.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Allegheny County Fire Academy, Pittsburgh Fire Fighters Local No. 1, Pittsburgh Bureau of Fire, and UPMC Prehospital Care. Special thanks to Chief Robert Full, Academy Director Al Wickline, and Staff Instructor Steve Imbarlina. Finally, we thank our subjects for their participation and dedication to the fire service. The results of this study do not imply endorsement by the American College of Sports Medicine.

This study was funded by the FEMA Assistance to Firefighters Grant Program (EMW-2006-FP-02245). This study was also supported in part by Grant Number UL1 RR024153 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

Footnotes

The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of FEMA, NCRR, or NIH.

Conflict of Interest The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this topic.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gisolfi CV, Wenger CB. Temperature regulation during exercise: oldc oncepts, new ideas. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1984;12:339–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gledhill N, Jamnik VK. Characterization of the physical demands of firefighting. Canadian Journal of Sport Sciences. 1992;17(3):207–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Heimburg ED, Rasmussen AK, Medbo JI. Physiological responses of firefighters and performance predictors during a simulated rescue of hospital patients. Ergonomics. 2006;49(2):111–26. doi: 10.1080/00140130500435793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malley KS, et al. Effects of fire fighting uniform (modern, modified modern, and traditional) design changes on exercise duration in New York City Firefighters. J Occup Environ Med. 1999;41(12):1104–15. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199912000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Fire Protection Association . NFPA 1584: Standard on the Rehabilitation Process for Members During Emergency Operations and Training Exercises. Quincy MA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clements JM, et al. Ice-Water Immersion and Cold-Water Immersion Provide Similar Cooling Rates in Runners With Exercise-Induced Hyperthermia. J Athl Train. 2002;37(2):146–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasegawa H, et al. Wearing a cooling jacket during exercise reduces thermal strain and improves endurance exercise performance in a warm environment. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19(1):122–8. doi: 10.1519/14503.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hostler D, et al. Comparison of active cooling devices with passive cooling for rehabilitation of firefighters performing exercise in thermal protective clothing: a report from the Fireground Rehab Evaluation (FIRE) trial. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2010;14(3):300–9. doi: 10.3109/10903121003770654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selkirk GA, McLellan TM, Wong J. Active versus passive cooling during work in warm environments while wearing firefighting protective clothing. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2004;1(8):521–31. doi: 10.1080/15459620490475216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett BL, et al. Comparison of two cool vests on heat-strain reduction while wearing a firefighting ensemble. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1995 doi: 10.1007/BF00865029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter JM, et al. Strategies to combat heat strain during and after firefighting. J Therm Biol. 2007;32(2):109–116. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giesbrecht GG, Jamieson C, Cahill F. Cooling hyperthermic firefighters by immersing forearms and hands in 10 degrees C and 20 degrees C water. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2007;78(6):561–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Fire Protection Association . NFPA 1001: Standard for professional firefighter qualifications. Quincy MA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson AS, Pollock ML. Generalized equations for predicting body density of men. British Journal of Nutrition. 1978;40:497–504. doi: 10.1079/bjn19780152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Fire Protection Association . NFPA 1403: Standard on live fireevolutions. Quincy MA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Fire Protection Association . NFPA 1971: Standard on protective ensembles for firefighting and proximity fire fighting. Quincy MA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petruzzello S, et al. Perceptual and physiological heat strain: Examination in firefighters in laboratory- and field-based studies. Ergonomics. 2009:1–8. doi: 10.1080/00140130802550216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith D, Manning T, et al. Effect of strenuous live-fire drills on cardiovascular and psychological responses of recruit firefighters. Ergonomics. 2001;44(3):244–54. doi: 10.1080/00140130121115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter JB, Banister EW, Morrison JB. Effectiveness of rest pauses and cooling in alleviation of heat stress during simulated fire-fighting activity. Ergonomics. 1999;42(2):299–313. doi: 10.1080/001401399185667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barr D, et al. A practical cooling strategy for reducing the physiological strain associated with firefighting activity in the heat. Ergonomics. 2009;52(4):413–20. doi: 10.1080/00140130802707675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hostler D, et al. Comparison of rehydration regimens for rehabilitation of firefighters performing heavy exercise in thermal protective clothing: A report from the Fireground Rehab Evaluation (FIRE) trial. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2010;14:194–201. doi: 10.3109/10903120903524963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Figueroa A, et al. Endurance training improves post-exercise cardiac autonomic modulation in obese women with and without type 2 diabetes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007;100(4):437–44. doi: 10.1007/s00421-007-0446-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seiler S, Haugen O, Kuffel E. Autonomic recovery after exercise in trained athletes: intensity and duration effects. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1366–73. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318060f17d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]