Abstract

Rationale

Fibrillation-defibrillation episodes in failing ventricles may be followed by action potential duration (APD) shortening and recurrent spontaneous ventricular fibrillation (SVF).

Objective

We hypothesized that activation of apamin-sensitive small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK) channels are responsible for the postshock APD shortening in failing ventricles.

Methods and Results

A rabbit model of tachycardia-induced heart failure was used. Simultaneous optical mapping of intracellular Ca2+ and membrane potential (Vm) was performed in failing and non-failing ventricles. Three failing ventricles developed SVF (SVF group), 9 did not (no-SVF group). None of the 10 non-failing ventricles developed SVF. Increased pacing rate and duration augmented the magnitude of APD shortening. Apamin (1 μmol/L) eliminated recurrent SVF, increased postshock APD80 in SVF group from 126±5 ms to 153±4 ms (p<0.05), in no-SVF group from147±2 ms to 162±3 ms (p<0.05) but did not change of APD80 in non-failing group. Whole cell patch-clamp studies at 36°C showed that the apamin-sensitive K+ current (IKAS) density was significantly larger in the failing than in the normal ventricular epicardial myocytes, and epicardial IKAS density is significantly higher than midmyocardial and endocardial myocytes. Steady-state Ca2+ response of IKAS was leftward-shifted in the failing cells compared with the normal control cells, indicating increased Ca2+ sensitivity of IKAS in failing ventricles. The Kd was 232 ± 5 nM for failing myocytes and 553 ± 78 nM for normal myocytes (p = 0.002).

Conclusions

Heart failure heterogeneously increases the sensitivity of IKAS to intracellular Ca2+, leading to upregulation of IKAS, postshock APD shortening and recurrent SVF.

Keywords: arrhythmia, intracellular calcium, ion channels, ventricular fibrillation

Introduction

Electrical storm describes a clinical condition in which the patients suffer from recurrent spontaneous ventricular fibrillation (SVF) requiring multiple defibrillation shocks within a short period of time.1 It occurs frequently in patients with heart failure (HF) and is an important reason for rehospitalization.2-4 In addition, recurrent SVF occurs in roughly half of the patients undergoing cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and may be associated with significant morbidity and mortality.3, 4 The mechanisms of electrical storm remain unclear. We recently developed a rabbit model of electrical storm with pacing-induced HF.5 In that model, acute but reversible postshock action potential duration (APD) shortening induced recurrent SVF by promoting late phase 3 early afterdepolarizations (EADs) and triggered activity. However, the mechanisms underlying acute APD shortening after fibrillation-defibrillation episodes in failing ventricles remain unclear. Because VF is associated with intracellular Ca2+ (Cai) accumulation, especially in failing ventricles,6-8 we hypothesized that apamin-sensitive small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK) channels may be in part responsible for postshock APD shortening. Apamin is a neurotoxin that selectively blocks SK channels.9, 10 Several studies show that apamin-sensitive K+ current (IKAS) is abundantly present in cardiac atrial cells but none in normal ventricular cells.10-16 We were not able to find any studies on IKAS regulation in heart failure (HF) ventricles. Therefore, we studied normal and HF rabbits to test the hypotheses that IKAS is significantly increased in HF rabbit ventricular myocytes and that IKAS blockade prevents postshock APD shortening and recurrent SVF in Langendorff-perfused HF ventricles.

Methods

An expanded Methods section is available in the Online Data Supplement. New Zealand white rabbits (N=39) were used in the study. Among them, 5 died during rapid pacing, 22 were used for optical mapping (including 12 with pacing-induced HF, 3 sham with pacemaker implanted but not paced and 7 normal control) and 12 were used for patch clamp studies (6 HF and 6 normal control).

Optical mapping studies

We simultaneously mapped intracellular Ca2+ (Cai) and membrane potential (Vm) using Rhod-2 AM and RH237, respectively, in ventricles of Langendorff-perfused hearts. Rapid ventricular pacing and 3 to 5 ventricular fibrillation (VF)-defibrillation episodes were mapped. Apamin (1 μmol/L) was added to the perfusate for 30 min before the same protocols were repeated. We then waited for 30 min to determine if the effects of apamin can be washed out.

Patch Clamp Studies

Whole-cell patch-clamp technique was used to record apamin-sensitive K+ currents (IKAS) in isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes. All experiments were performed at 36°C. To study Ca2+-dependence of IKAS, various combinations of EGTA and CaCl2 were used in the pipette solutions.

Real-time PCR

Ventricular tissues were sampled from 5 normal and 5 HF rabbits prior to cell isolation for patch-clamp studies. Real-time PCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix with iCycler (BioRad, Hercules, CA).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS PASW Statistics 17 software (IBM, Chicago, IL). We used Student's t-test for a comparison between two groups. One-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni tests were performed for comparisons among three or more groups. A p≤0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Evidence of HF

All rabbits that survived the rapid pacing protocol showed clinical signs of HF, including appetite loss, tachypnea, lethargy, pleural effusion, ascites, and visible congestion of lung, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. Echocardiograms of sham-operated rabbits (N=3) at baseline and at second surgery showed no changes of left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic dimension (12.5±0.9 mm vs 13.0±0.6 mm), end-systolic dimension (6.5±1.5 mm vs 6.9±1.7 mm), or fractional shortening (0.49±0.08 vs 0.48±0.11) (p=NS for all comparisons). In contrast, HF rabbits (N=13) showed significant increases in end-diastolic dimension (14.5±0.2 mm vs 19.9±0.5 mm) and in end-systolic dimension (8.4±0.3 mm vs 17.9±0.3 mm) and reduced fractional shortening (0.42±0.01 vs 0.10±0.01) (P<0.05 for all comparisons). The percent LV fibrosis was 5 %±1 % for normal (N=3) or sham-operated hearts and 21 %±6 % for failing hearts (N=5) (P<0.05). Action potential duration measured at 80% repolarization (APD80) with pacing cycle length (PCL) of 300 ms were not different between sham-operated and normal rabbits (166±5 ms vs 168±2 ms, p>0.05). Therefore, these data were combined into a single non-failing group. There were no significant differences in RR intervals during the sinus rhythm between non-failing and failing hearts (464±38 ms vs 509±42 ms, p=NS). Figure 1A shows marked cardiac enlargement (right panel) typical for all failing hearts. Action potential duration (APD) prolongation was present in all failing ventricles. Figure 1B shows APD80 at 300 ms PCL recorded from the site marked by an asterisk in APD80 maps in Figure 1C. Overall, the failing ventricles (N=7) had a longer APD80 than non-failing ventricles (N=7) (181±5 ms vs 167±2 ms, p<0.05, Figure 1D). The Cai transient duration at 80% repolarization (CaiTD80) was 184±5 ms for failing ventricles and 176±3 ms for non-failing ventricles (p=NS).

Figure 1. Action potential duration (APD) and intracellular Ca transient duration (CaiTD) in non-failing and failing ventricles.

Measurements were made with pacing cycle length (PCL) of 300 ms in 7 non-failing (including 4 normal and 3 sham-operated ventricles) and 7 failing ventricles. A, Non-failing and failing hearts. B, The black and red lines indicate optical tracings of membrane potential (Vm) and intracellular calcium (Cai), respectively. The optical tracings were recorded from the site labeled by an asterisk in APD80 map and CaiTD80 map in C. C, APD80 map (upper panels) and CaiTD80 map (lower panels) obtained from normal (left panels) and failing ventricles (right panels). Averages of APD80 and CaiTD80 in the study were measured from all pixels in the map, excluding the atrial signals and the pixels at the edge of ventricles. D, Average of APD80 and CaiTD80 at fixed PCL of 300 ms in 7 non-failing and 7 failing ventricles. Bar graphs represent mean±SEM; APD80 and CaiTD80 indicate APD and Cai transient duration, respectively, measured at 80% repolarization; HF, heart failure; no-HF, non-failing heart; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

Effects of Apamin on Acute APD Shortening and Postshock SVF

After fibrillation-defibrillation episodes, acute but transient shortening of APD occurred in all 12 failing ventricles. Three of them developed SVF in the postshock period (the “SVF-Group”). Figure 2A, left panel, shows Vm (black line) and Cai (red line) optical signals recorded during one of the SVF episodes. There were 2 postshock beats (1 and 2) before VF termination. Optical maps confirmed complete cessation of wavefronts after beat 2, consistent with type B successful defibrillation.17 However, there was a large Cai transient and short APD (beat 3). The first beat of SVF (beat 4) began during late phase 3 of the preceding sinus beat. In Figure 2A(b), an isochronal map illustrates that beat 4 originated from the basal portion of the RV. The right two columns are ratio maps of Vm and Cai, respectively, of the same beat. The Cai remained elevated throughout the mapped field while Vm had already repolarized. The focal beat originated from the left upper quadrant during persistent Cai elevation, consistent with the late phase 3 EAD mechanism.5, 18 Five SVF episodes were recorded after initial successful defibrillation in this failing heart. Apamin prevented both the postshock APD shortening and SVF (Figure 2B). We repeated fibrillation-defibrillation episodes four times, but no SVF was observed in the postshock period after apamin. Among the 12 failing ventricles studied, 3 developed a total of 11 episodes of SVF 104±23 sec after initial successful defibrillation. Apamin administration completely prevented SVF after 3-5 repeated fibrillation-defibrillation episodes. Figure 3A shows additional optical traces and APD80 map during baseline sinus rhythm (SRm) and during a fibrillation-defibrillation episode in a ventricle with postshock SVF. Upper panels illustrate optical traces of sinus rhythm and in the postshock period in the absence of apamin. Acute APD shortening occurred after defibrillation while Cai remained elevated after repolarization (beats 1 and 2). The difference between CaiTD80 and APD80 is shown in the CaiTD80-APD80 map. A large difference was present between CaiTD80 and APD80 in beats 1 and 2. After pretreatment with apamin, beats 1 and 2 after defibrillation had less APD shortening as compared with baseline, associated with smaller differences between CaiTD80 and APD80 (Figure 3B). The pseudoECG tracings in panels A(b) and B(b) show recurrent SVF in the absence of apamin (A) but not in the presence of apamin (B). We were not able to washout apamin effects in any of the 12 failing ventricles.

Figure 2. Pretreatment with apamin prevents refibrillation.

The black and red lines indicate optical tracings for Vm and Cai, respectively, obtained from the endocardial surface in a failing ventricle. A(a), Before apamin, a defibrillation shock (arrow) was followed by two postshock beats (1 and 2). Optical maps (not shown) confirmed complete cessation of wavefronts after beat 2, consistent with type-B successful defibrillation. After a short pause, there was a large Cai transient (red dot), short APD (beat 3) and first beat (beat 4) of SVF arising from late phase 3. A(b), Snapshots of Cai and Vm ratio maps at times from 10 ms before to 20 ms after the onset of beat 4. Note Cai remained elevated throughout the mapped field while Vm has already repolarized. The beat 4 arose during persistently high Cai and initiated the SVF. B, After apamin (1 μM) infusion, the postshock beats (5 and 6) had longer APD than the beats 1-4 in A. The APD and CaiTD were approximately the same, and SVF episodes were completely prevented. PM, papillary muscle; S, interventricular septum; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 3. Effects of apamin (1 μM) on ΔAPD80 and the differences between CaiTD80 and APD80 in SVF Group.

Optical traces (upper panels) of Vm (black line) and Cai (red line) were recorded from site marked by an asterisk in APD80 map (lower panels) in a second heart of the SVF Group. A(a), Epicardial optical traces of Vm and Cai and APD80 map during sinus rhythm before pacing-induced VF (left panels). Right upper panel shows beats 1 and 2 had acute shortening of APD in the immediate postshock period, resulting in the Cai elevation during late phase 3 and phase 4. Lower panel shows the corresponding APD80 maps, and the maps of the difference between CaiTD80 and APD80 in beats 1 and 2. A(b), pseudoECG of the same heart, showing a SVF episode 74 sec after initial successful defibrillation. B(a), After apamin, the postshock beats 1 and 2 had longer APD80 than those before apamin (A(a)). The CaiTD80 was similar to that in A, and the differences between CaiTD80 and APD80 in beats 1 and 2 were reduced. B(b), pseudoECG show the absence of SVF after initial successful defibrillation. Arrow indicates defibrillation; PI VF, pacing-induced VF; SRm, Sinus rhythm.

In four of the 12 failing hearts, we also studied different doses of apamin on postshock APD80. The results show that apamin concentration of 0.1, 0.3 and 1.0 μmol/L prolonged postshock APD80 to similar duration while 0.01 μmol/L apamin had little effects on postshock APD80 (online Figure I).

Effects of Apamin on Baseline APD

Examples of APD80 maps (bottom panel) and corresponding optical traces of action potentials from a single representative pixel (top panel) are presented in Figure 4A. Apamin induced more APD80 prolongation in failing than in non-failing ventricles at PCL of 300 ms. The APD prolongation predominantly occurred in the terminal portion of repolarization. Figure 4B shows the magnitude of APD80 prolongation map obtained from the same non-failing and failing ventricles presented in figure 4A. At PCL of 300 ms, the percentage of APD prolongation with apamin was 5.4±0.7 % for failing ventricles compared with 1.4±0.6 % in non-failing ventricles (p<0.05) (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Effect of apamin in non-failing and failing ventricles.

Measurements of APD80 were made with PCL of 300 ms. A, The black and blue lines (upper panels) indicate the optical Vm tracing before and after application of apamin, respectively. The tracings were obtained from the site labeled by an asterisk in the APD80 map (lower panels). B, Examples of ΔAPD80 map after apamin in non-failing and failing ventricles. C, Magnitude of APD80 prolongation before and after apamin in 7 non-failing and 7 failing ventricles. Bar graphs represent means±SEM.

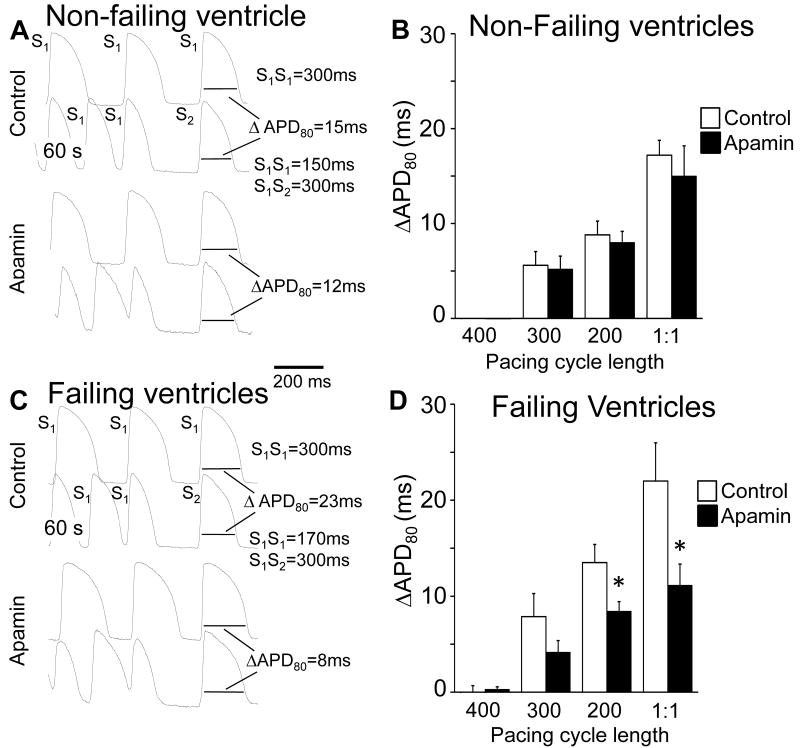

Effects of Apamin on APD After Rapid Pacing

We used rapid pacing to increase Cai. After abrupt cessation of rapid ventricular pacing, APD shortening (ΔAPD80) was greater in failing than in non-failing ventricles. The dependence of ΔAPD80 on the PCL (Pacing Protocol I) and pacing duration (Pacing Protocol II) are presented in Figure 5 and online Figure II, respectively. The shorter PCL and longer pacing duration elicited more APD shortening, and apamin reduced ΔAPD80 after these rapid pacing protocols in failing ventricles. Figure 5A shows the effects of Pacing protocol I on ΔAPD80 in a non-failing ventricle at baseline (control) and after apamin administration. Figure 5B shows that apamin did not significantly change ΔAPD80 in non-failing ventricles. Figure 5C shows an example obtained from a failing ventricle with Pacing Protocol I. In this example, apamin reduced ΔAPD80 from 23 ms to 8 ms. Figure 3D summarizes the effects of apamin in failing ventricles. Apamin significantly reduced ΔAPD80 in failing but not in non-failing ventricles. Similar results were noted for the dependence of ΔAPD80 on pacing duration (pacing protocol II, online Figure II).

Figure 5. APD after cessation of rapid pacing.

In A and C, the first and 3rd row show action potential at fixed-rate pacing at 300 ms PCL. The 2nd and 4th rows show action potentials during rapid pacing followed by a post-pacing beat. The preceding cycle length of the first post-pacing beat was controlled by an S2 given 300 ms after the last S1. The APD of the first post-pacing beat was measured to 80% repolarization (APD80). The same pacing protocol was performed at baseline and after apamin (1 μM). B, The effect of apamin on ΔAPD80 in all non-failing ventricles studied. D, The effects of apamin in all failing ventricles studied. Bar graphs represent means±SEM, “1:1” indicates the shortest PCL associated with 1:1 capture. * p<0.05 vs control.

Effects of Apamin on Postshock APD in no-SVF Group

In 9 of 12 failing ventricles, SVF did not occur after fibrillation-defibrillation episodes (the “no-SVF” Group).5 Similar to the SVF Group, acute APD shortening was also observed in this group after a fibrillation-defibrillation episode. Figure 6A shows the optical tracing and corresponding APD80 maps in sinus rhythm (left panels) and after defibrillation (right panels) in a failing ventricle without SVF. Similarly, apamin prolonged the APD immediately after defibrillation shock in failing ventricles that did not develop SVF (Figure 6A(b)). Note the difference between CaiTD80 and APD80 was reduced by apamin. In contrast, no acute shortening of APD was observed immediately after a successful defibrillation shock in non-failing ventricles. Pretreatment with apamin did not result in significant APD changes in non-failing ventricles (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Effects of apamin on postshock APD in no-SVF Group and non-failing hearts.

A (a), Left panels shows baseline Vm (black line) and Cai (red line) recorded from site marked by an asterisk in APD80 map during baseline sinus rhythm. Right upper panel shows postshock beats 1 and 2. Right lower panel shows the APD80 maps, and the differences between CaiTD80 and APD80 maps in beats 1 and 2. B, An example of non-failing heart. As compared with Control (B(a)), there were little changes of APD and CaiTD after defibrillation when the tissues were pretreated with apamin (B(b)). SRm, Sinus rhythm.

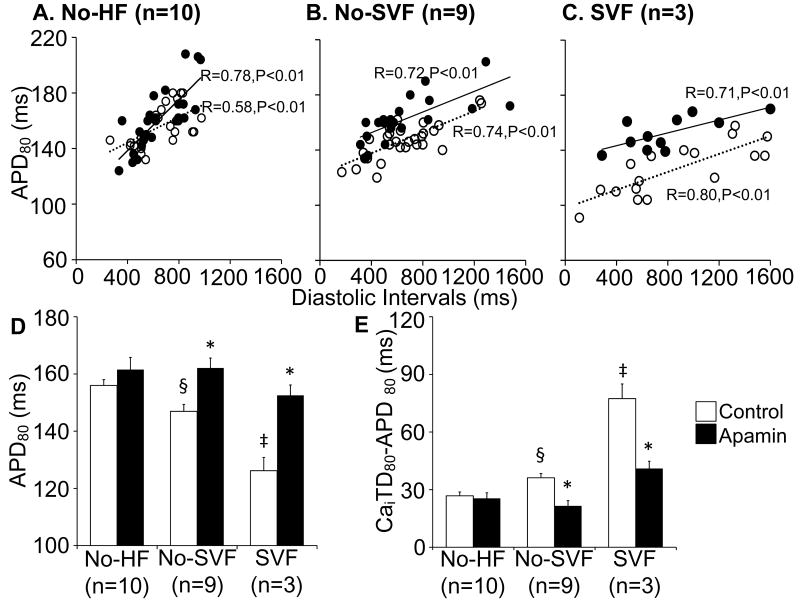

Postshock APD Changes of All Ventricles Studied

We plotted APD80 of the first two postshock beats against the preceding diastolic interval (DI) for all episodes. Apamin did not change postshock APDs in non-failing ventricles (figure 7A), but prolonged postshock APDs significantly in failing ventricles of both the no-SVF Group (Figure 7B) and in the SVF Group (Figure 7C). We performed statistical analyses with repeated-measure ANOVA to compare the ΔAPD80 before and after apamin. The ΔAPD80 was 5.8 ms (-2.2 ms to 13.8 ms; p=NS) for non-failing ventricles, indicating that apamin did not significantly change the postshock APD. For no-SVF and SVF groups of failing ventricles, the ΔAPD80 was 15.7 ms (9.4 ms to 21.9 ms, p<0.001) and 27.4 ms (14.3 ms to 40.4 ms, p<0.001), respectively, showing that postshock APD was lengthened significantly by apamin.

Figure 7. Effects of apamin in failing ventricles.

A through C, Postshock APD80 versus diastolic interval in non-failing ventricles (A), failing ventricles without SVF (B) and with SVF (C) of all hearts studied. The postshock APD80 without apamin (unfilled circles) are shorter than with apamin (filled circles) in failing ventricles (B and C) but not in non-failing ventricles (A). D and E, Bar graphs show postshock APD80 and the difference between postshock APD80 and CaiTD80 with and without apamin in non-failing, no-SVF and SVF groups. Bar graphs represent means±SEM. * p<0.05 vs control; § p<0.05 vs no-HF group; ‡ p<0.05 vs no-HF and no-SVF group.

We investigated the postshock APD80 and the differences between CaiTD80 and APD80 in all ventricles studied. The results are presented in Figure 7D and 7E, respectively. There were no significant differences in VF duration before versus after apamin in non-failing ventricles (324±14 sec vs 338±16 sec, p=NS), no-SVF (353±33 sec vs 352±44 sec, p=NS), and SVF (336±43 sec vs 362±33 sec, p=NS) groups. Before apamin, the postshock APD80 shortened to 147±2 ms, 126±5 ms and 156±2 ms (p<0.05) in no-SVF group, SVF group and non-failing ventricles, respectively. Apamin minimized acute transient postshock APD80 shortening in failing ventricles but not in non-failing ventricles. Specifically, apamin increased postshock APD80 in no-SVF group from147±2 ms to 162±3 ms (p<0.05) and in SVF group from 126±5 ms to 153±4 ms (p<0.05). There was no change of APD80 in non-failing group before (156±2 ms) and after apamin (162±4 ms, p=NS). The differences between CaiTD80 and APD80 were also decreased with apamin in no-SVF (36±2 ms vs 22±3 ms, p<0.05) and SVF (77±8 ms vs 41±4 ms, p<0.05) groups but not in non-failing group (27±2 ms vs 25±3 ms).

Effects of Glibenclamide on ΔAPD80 in Failing Ventricles

To determine if ATP-sensitive potassium current (IKATP) activation was responsible for the APD shortening in failing ventricles, we examined the effect glibenclamide (10 μmol/L), which mainly inhibit IKATP channel in this range of concentrations,19 in 3 failing ventricles. As shown in online Figure III, glibenclamide did not significantly affect the magnitude of post-rapid pacing and postshock APD shortening compared with control.

IKAS in Failing Ventricles

The density and properties of IKAS were examined in cardiomyocytes isolated from normal and failing rabbit left ventricles using the voltage-clamp technique in whole-cell mode. Figure 8A shows representative current traces obtained with a step-pulse protocol (300 ms pulse duration; holding potential, -50 mV; see inset) in the absence and presence of 100 nM apamin in the bath solution. Mean IKAS density (determined as the apamin-sensitive difference current) was significantly larger in failing than in normal ventricular epicardial myocytes (IKAS density at 0 mV with an intrapipette free-Ca2+ of 863 nM: 8.39 ± 1.00 pA/pF, n = 6 cells from 5 failing rabbits, vs. 2.83 ± 0.87 pA/pF, n = 6 cells from 4 normal rabbits, p < 0.01). In contrast, when the intrapipette free-Ca2+ was buffered to 100 nM, the apamin-sensitive current was much smaller, with no significant difference between normal and failing ventricular myocytes (Fig. 8D). Figure 8B illustrates the IKAS-voltage (I-V) relationships. Transmural distribution of IKAS in failing ventricles was studied using cardiomyocytes isolated from three layers (6 epicardial cells, 5 midmyocardial cells, and 7 endocardial cells from 5 animals). Mean IKAS density in epicardial myocytes (8.52±2.47 pA/pF, range 5.21-11.46 pA/pF) was significantly larger than midmyocardial cells (2.18±2.14 pA/pF, range 0.00-5.70 pA/pF) and endocardial cells (1.87±2.36 pA/pF, range 0.00-6.04 pA/pF) (Figure 8C). To further elucidate the mechanisms underlying IKAS upregulation, Ca2+-dependence of IKAS was studied in epicardial cells using pipette solutions containing increasing intracellular free Ca2+ concentrations. Figure 8D demonstrates that the steady-state Ca2+ response of IKAS was leftward-shifted in the failing cells compared with the normal cells. The data were fitted with the Hill equation, yielding Kd of 232 ± 5 nM for failing and 553 ± 78 nM (p=0.002) for normal cells, and Hill coefficients of 2.38 ± 0.13 for failing and 1.50 ± 0.30 for normal cells (p = 0.01). These results are compatible with the notion that the K+ channels carrying IKAS have increased sensitivity to cytosolic Ca2+ in failing ventricles.

Figure 8. Apamin-sensitive currents (IKAS) in failing rabbit ventricles.

(A) Representative K+ current traces obtained from normal (upper panel) and failing (lower panel) ventricular myocytes. Voltage-pulse protocol is shown in the inset. “Baseline” shows current traces in the absence of apamin (Ibaseline); “Apamin 100 nM” shows currents in the presence of 100 nM apamin (Iapamin); “Difference” shows IKAS calculated as Ibaseline – Iapamin. (B) IKAS-voltage (I-V) relationship obtained from normal (N=6) and failing (N=6) ventricular epicardial cells. (C) IKAS density at 0 mV with an intrapipette free-Ca2+ of 863 nM recorded from epicardial (Epi), midcardial (Mid), and endocardial (Endo) cells from 5 failing ventricles. *p<0.05. (D) Steady-state Ca2+ response of IKAS in normal and failing epicardial ventricular myocytes. The data were fitted with the Hill equation: y = 1/[1 + (Kd/X)n], where y represents the IKAS normalized to the currents with 10 μM intrapipette Ca2+; x is the concentration of Ca2+; Kd is the concentration at half-maximal activation; and n is the Hill coefficient. Error bars represent SEM. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of cells patched.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

The SK2 mRNA levels (normalized to GAPDH) in normal (N=5) and failing (N=5) ventricles were 100±16.4% and 118±8.5%, respectively (p=0.39).

Discussion

The primary finding of this study is that heart failure heterogeneously increases the sensitivity of IKAS to intracellular Ca2+, leading to upregulation of IKAS, postshock APD shortening and recurrent SVF.

IKAS in the Normal and Failing Ventricles

The primary function SK channels in the nervous system is to produce afterhyperpolarization following a neural action potential and to protect the cell from the deleterious effects of continuous tetanic activity.20 Seminal studies from multiple laboratories show that SK channels are also expressed in cardiac cells, more so in the atria than in the ventricles.10-16 These findings suggest that specific ligands for SK currents may offer a unique therapeutic opportunity to directly modify atrial cells without interfering with ventricular myocytes.12 Our study confirmed that IKAS plays little role in APD regulation in normal ventricles. However, the same is not true for failing ventricles in which IKAS is upregulated in epicardial cells. Previous studies showed that multiple ventricular K+ currents (Ito, IK1, IKr and IKs) are downregulated in animal models of HF, contributing to the reduced repolarization reserve.21 In addition, ATP-sensitive K+ currents (IKATP) are also disrupted in HF. The IKATP, which shortens APD and protects the heart from Cai overload, is essential in maintaining the homeostasis during the metabolically demanding adaptive response to stress.22 In a model of HF induced by transgenic expression of the cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha, structural remodeling in failing ventricles led to disruption of energetic signal-channel communication, resulting in disturbing the IKATP-mediated protection.23 Another study24 shows that IKATP channel activation under metabolic stress was impaired in myocytes from rat hypertrophied ventricle. Our study found that suppression of IKATP did not reduce post-pacing or postshock APD shortening in failing ventricles, but apamin significantly reduced the magnitude of post-pacing or postshock APD shortening. Taken together, these findings suggest that because of IKATP channel malfunction and downregulation of multiple other K+ currents, the failing ventricles may rely on IKAS to shorten the APD in situations of Cai overload.

Late Phase 3 EAD and Ventricular Arrhythmogenesis

When heart rate increases, APD shortens physiologically to preserve a sufficient diastolic interval for ventricular filling and coronary flow. However, excessive APD shortening might be arrhythmogenic by promoting late phase 3 EAD18 or by inducing transmural heterogeneity of repolarization.25 Because of SERCA downregulation26 and decreased driving force of Na+/Ca2+ exchange current,27 myocytes in failing hearts have higher diastolic Cai concentration, slower Cai transient decay, and more Cai accumulation during burst pacing than those in normal hearts. Therefore, during rapid pacing or fibrillation in failing ventricles, the rapid depolarization may increase Cai which in turn activates IKAS and shortens APD in a spatially heterogeneous fashion. Marked APD shortening after fibrillation-defibrillation episodes with persistent Cai elevation during the late phase 3 of action potential results in the development of late phase 3 early afterdepolarization and recurrent SVF in failing hearts.5

Heterogeneous Remodeling of IKAS

The upregulation of IKAS during HF is highly heterogeneous. Although epicardial cells in average gained much more IKAS density than midmyocardial and endocardial cells during HF, large variations of IKAS density is present within the same layer of cells. Previous studies showed that strong intercellular coupling can reduce the differences of APD between different layers of cells, making M cells “invisible” in intact human ventricles.28 Similarly, the highly heterogeneous distribution of IKAS density and the tight intercellular coupling of intact ventricles allowed cells with high IKAS density and shortened APD to influence the APD of the neighboring cells with low IKAS density. Therefore, optical mapping studies showed that postshock APD shortening occurs both in the epicardium and in the endocardium, and that apamin prevented postshock APD shortening in both layers of the ventricles.

Clinical Implications

Recurrent SVF (electrical storm) is a frequent complication in patients with advanced HF.2 A recent genome wide association study29 showed that variants at the 1q21 locus cluster at KCNN3 (SK3) is associated with atrial fibrillation. The knowledge that IKAS is upregulated in HF should direct broader studies into the role of such currents in determining heart disease risk and as possible targets for preventive therapy in both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias.

Study Limitations

Apamin is a neural toxin and may induce significant neurological side effects when used in live animals and in humans. Therefore, it is necessary to develop non-toxic blockers of IKAS before we can test the effects of IKAS blockade on VF storm in human patients. Another limitation is that apamin is a potent inhibitor of the L-type Ca current (ICa,L).30 While ICa,L blockade cannot be used to explain APD lengthening after fibrillation-defibrillation episodes, this pharmacological effect could help prevent SVF. Therefore, whether or not apamin prevented SVF by IKAS blockade or by a combined effects of IKAS and ICa,L blockade remain unclear.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Larry Jones for his inputs, Jian Tan, Yanhua Zhang and Lei Lin for assistance, and Dr Xiaohong Zhou of Medtronic, Inc., for providing the pacing system used in this study.

Sources of Funding: This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants P01 HL78931, R01 HL78932, and 71140; a Nihon Kohden/St Jude Medical electrophysiology fellowship (Dr Maruyama); an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award (Dr Lin) and a Medtronic- Zipes endowments (Dr Chen).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- APD

action potential duration

- Cai

intracellular calcium

- CaiTD

intracellular calcium transient duration

- EADs

early afterdepolarizations

- HF

heart failure

- IKAS

apamin-sensitive potassium current

- IKATP

ATP-sensitive potassium current

- LV

left ventricle

- PCL

pacing cycle length

- SK

small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels

- SRm

sinus rhythm

- SVF

spontaneous ventricular fibrillation

- Vm

membrane potential

- VF

ventricular fibrillation

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Huang DT, Traub D. Recurrent ventricular arrhythmia storms in the age of implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy: A comprehensive review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;51:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gatzoulis KA, Andrikopoulos GK, Apostolopoulos T, Sotiropoulos E, Zervopoulos G, Antoniou J, Brili S, Stefanadis CI. Electrical storm is an independent predictor of adverse long-term outcome in the era of implantable defibrillator therapy. Europace. 2005;7:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.eupc.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korte T, Jung W, Ostermann G, Wolpert C, Spehl S, Esmailzadeh B, Luderitz B. Hospital readmission after transvenous cardioverter/defibrillator implantation; a single centre study. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:1186–1191. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lunati M, Gasparini M, Bocchiardo M, Curnis A, Landolina M, Carboni A, Luzzi G, Zanotto G, Ravazzi P, Magenta G, Denaro A, Distefano P, Grammatico A. Clustering of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in heart failure patients implanted with a biventricular cardioverter defibrillator. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:1299–1306. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogawa M, Morita N, Tang L, Karagueuzian HS, Weiss JN, Lin SF, Chen PS. Mechanisms of recurrent ventricular fibrillation in a rabbit model of pacing-induced heart failure. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:784–792. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeh YH, Wakili R, Qi XY, Chartier D, Boknik P, Kaab S, Ravens U, Coutu P, Dobrev D, Nattel S. Calcium-handling abnormalities underlying atrial arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in dogs with congestive heart failure. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:93–102. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.107.754788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baartscheer A, Schumacher CA, Belterman CN, Coronel R, Fiolet JW. Sr calcium handling and calcium after-transients in a rabbit model of heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00854-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koretsune Y, Marban E. Cell calcium in the pathophysiology of ventricular fibrillation and in the pathogenesis of postarrhythmic contractile dysfunction. Circulation. 1989;80:369–379. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castle NA, Haylett DG, Jenkinson DH. Toxins in the characterization of potassium channels. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:59–65. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Q, Timofeyev V, Lu L, Li N, Singapuri A, Long MK, Bond CT, Adelman JP, Chiamvimonvat N. Functional roles of a ca2+-activated k+ channel in atrioventricular nodes. Circ Res. 2008;102:465–471. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu Y, Tuteja D, Zhang Z, Xu D, Zhang Y, Rodriguez J, Nie L, Tuxson HR, Young JN, Glatter KA, Vazquez AE, Yamoah EN, Chiamvimonvat N. Molecular identification and functional roles of a ca(2+)-activated k+ channel in human and mouse hearts. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49085–49094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li N, Timofeyev V, Tuteja D, Xu D, Lu L, Zhang Q, Zhang Z, Singapuri A, Albert TR, Rajagopal AV, Bond CT, Periasamy M, Adelman J, Chiamvimonvat N. Ablation of a ca2+-activated k+ channel (sk2 channel) results in action potential prolongation in atrial myocytes and atrial fibrillation. J Physiol. 2009;587:1087–1100. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozgen N, Dun W, Sosunov EA, Anyukhovsky EP, Hirose M, Duffy HS, Boyden PA, Rosen MR. Early electrical remodeling in rabbit pulmonary vein results from trafficking of intracellular sk2 channels to membrane sites. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:758–769. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagy N, Szuts V, Horvath Z, Seprenyi G, Farkas AS, Acsai K, Prorok J, Bitay M, Kun A, Pataricza J, Papp JG, Nanasi PP, Varro A, Toth A. Does small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel contribute to cardiac repolarization? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:656–663. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandler NJ, Greener ID, Tellez JO, Inada S, Musa H, Molenaar P, DiFrancesco D, Baruscotti M, Longhi R, Anderson RH, Billeter R, Sharma V, Sigg DC, Boyett MR, Dobrzynski H. Molecular architecture of the human sinus node: Insights into the function of the cardiac pacemaker. Circulation. 2009;119:1562–1575. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.804369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuteja D, Xu D, Timofeyev V, Lu L, Sharma D, Zhang Z, Xu Y, Nie L, Vazquez AE, Young JN, Glatter KA, Chiamvimonvat N. Differential expression of small-conductance ca2+-activated k+ channels sk1, sk2, and sk3 in mouse atrial and ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2714–2723. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00534.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang NC, Lee MH, Ohara T, Okuyama Y, Fishbein GA, Lin SF, Karagueuzian HS, Chen PS. Optical mapping of ventricular defibrillation in isolated swine right ventricles: Demonstration of a postshock isoelectric window after near-threshold defibrillation shocks. Circulation. 2001;104:227–233. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burashnikov A, Antzelevitch C. Reinduction of atrial fibrillation immediately after termination of the arrhythmia is mediated by late phase 3 early afterdepolarization-induced triggered activity. Circulation. 2003;107:2355–2360. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065578.00869.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosati B, Rocchetti M, Zaza A, Wanke E. Sulfonylureas blockade of neural and cardiac herg channels. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:125–130. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01444-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bond CT, Maylie J, Adelman JP. Small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;868:370–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nattel S, Maguy A, Le BS, Yeh YH. Arrhythmogenic ion-channel remodeling in the heart: Heart failure, myocardial infarction, and atrial fibrillation. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:425–456. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kane GC, Liu XK, Yamada S, Olson TM, Terzic A. Cardiac katp channels in health and disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:937–943. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodgson DM, Zingman LV, Kane GC, Perez-Terzic C, Bienengraeber M, Ozcan C, Gumina RJ, Pucar D, O'Coclain F, Mann DL, Alekseev AE, Terzic A. Cellular remodeling in heart failure disrupts k(atp) channel-dependent stress tolerance. EMBO J. 2003;22:1732–1742. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimokawa J, Yokoshiki H, Tsutsui H. Impaired activation of atp-sensitive k+ channels in endocardial myocytes from left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3643–3649. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01357.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antzelevitch C. Heterogeneity and cardiac arrhythmias: An overview. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:964–972. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arai M, Matsui H, Periasamy M. Sarcoplasmic reticulum gene expression in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Circ Res. 1994;74:555–564. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baartscheer A, Schumacher CA, Belterman CN, Coronel R, Fiolet JW. [na+]i and the driving force of the na+/ca2+-exchanger in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:986–995. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00848-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conrath CE, Wilders R, Coronel R, de Bakker JM, Taggart P, de Groot JR, Opthof T. Intercellular coupling through gap junctions masks m cells in the human heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;62:407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellinor PT, Lunetta KL, Glazer NL, Pfeufer A, Alonso A, Chung MK, Sinner MF, de Bakker PI, Mueller M, Lubitz SA, Fox E, Darbar D, Smith NL, Smith JD, Schnabel RB, Soliman EZ, Rice KM, Van Wagoner DR, Beckmann BM, van Noord C, Wang K, Ehret GB, Rotter JI, Hazen SL, Steinbeck G, Smith AV, Launer LJ, Harris TB, Makino S, Nelis M, Milan DJ, Perz S, Esko T, Kottgen A, Moebus S, Newton-Cheh C, Li M, Mohlenkamp S, Wang TJ, Kao WH, Vasan RS, Nothen MM, MacRae CA, Stricker BH, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, Levy D, Boerwinkle E, Metspalu A, Topol EJ, Chakravarti A, Gudnason V, Psaty BM, Roden DM, Meitinger T, Wichmann HE, Witteman JC, Barnard J, Arking DE, Benjamin EJ, Heckbert SR, Kaab S. Common variants in kcnn3 are associated with lone atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet. 2010;42:240–244. doi: 10.1038/ng.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bkaily G, Sculptoreanu A, Jacques D, Economos D, Menard D. Apamin, a highly potent fetal l-type ca2+ current blocker in single heart cells. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:H463–471. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.2.H463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.