Abstract

Early adolescence is a critical transition period for the maintenance of academic achievement. One factor that school systems often fail to take into account is the influence of friends on academic achievement during middle school. This study investigated the influence of friends’ characteristics on change in academic achievement from Grade 6 through 8, and the role of students’ own characteristics as moderators of this relationship. The sample included 1,278 participants (698 girls). Linear regressions suggest that students with academically engaged friends may achieve to levels higher than expected in Grade 8. However, when considering the significant, negative influence of friends’ problem behavior, the role of friend's school engagement became nonsignificant. Low-achieving girls who had high-achieving friends in Grade 6 had lower academic achievement than expected by Grade 8. In contrast, high-achieving girls seemed to benefit from having high-achieving friends. Implications for theory and prevention efforts targeting young adolescents are discussed.

Keywords: academic achievement, friendship, middle school students, student engagement, behavior problems

Middle School Friendships and Academic Achievement in Early Adolescence: A Longitudinal Analysis

Early adolescence is a time of important social transitions, including changes in relationships with parents (Paikoff & Brooks-Gunn, 1991) and movement toward the peer group (Dishion, Nelson, & Bullock, 2004). The social transition into middle school does not necessarily accommodate or address these developmental changes (Eccles, Lord, & Buchanan, 1996). During this transition, students leave their small, intimate, and well-structured elementary schools with familiar peers to enter larger and more impersonal middle schools that include unfamiliar peers. In middle school, students commonly have several teachers, so it is challenging for educators to have the deep relationships with their pupils that elementary school teachers have. At the same time, schoolwork becomes more difficult and students are required to be more autonomous in the management of their work. Because early adolescents are required to adapt to many changes in their academic routines and social life, it is not surprising that some youth experience stress, behavioral changes, and declining academic achievement (Alspaugh, 1998; B. K. Barber & Olsen, 2004). Such a decline is not trivial; academic difficulties in middle school may pave the way for long-term patterns of academic failure, school dropout, and problems entering a fulfilling career in adulthood (Alexander, Entwisle, & Kabbani, 2001; Muthén & Khoo, 1998).

Students’ friendships are an aspect of the middle school experience that receives too little attention from scientists and policymakers. This oversight is potentially serious because early adolescence is a developmental stage during which peers can powerfully influence youngsters’ long-term developmental trajectories (Dishion, Nelson, & Bullock, 2004; Patterson, 1993). Because friendships become increasingly important at this age (Buchmann & Dalton, 2002; Furman, 1982), we focused this study on the role of friends’ characteristics as a predictor of change in students’ academic achievement during the middle school years.

Friends’ Characteristics and Academic Achievement

Peer group compositions often change as children enter middle school and have more opportunities to create new friendships. Hartup (1996) reviewed evidence showing that adolescents initially associate with peers who resemble themselves in terms of behavior, interests, and attitudes, and subsequently reinforce in each other those characteristics that brought them together in the first place. This leads conventional friends to further comply with social norms, whereas antisocial friends engage in increasingly problematic behavior. The term selection refers to this process of “asssortative pairing” through which individuals choose friends who share their attitudes and behavior, and socialization refers to friends’ mutual influence on their behaviors and attitudes (Kandel, 1978). Both are important aspects of early adolescent changes in academic engagement and in problem behavior (Reitz, Dekovic, Meijer, & Engels, 2006; Woolley, Kol, & Bowen, 2009). Friends’ characteristics therefore constitute an important factor to take into account when trying to predict changes in an individual's adjustment trajectory.

Friends’ problem behaviors

Students who engage in deviant behavior and substance use may encourage their friends to engage in activities that are incompatible with school success and that will eventually undermine school achievement (Finn, 1989; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992). Vitaro, Brendgen, and Wanner (2005) studied trajectories of associations with delinquent friends by using a global measure of delinquency that included problem behaviors such as aggression, destruction, and substance use. They found that participants whose friends displayed higher levels of delinquency between age 10 and 13 years had lower levels of academic achievement during the same period than did participants who affiliated with friends with lower levels of delinquent behavior. Yet, friends’ influences are not always negative, and a more complete understanding of friends’ contributions could be gained by taking into account other characteristics of students’ friends. Specifically, we hypothesize that well-adjusted friends have the potential to play a positive role in adolescents’ academic development.

Friends’ academic achievement

Previous research supports the hypothesis that friends’ academic achievement plays a positive role in the context of middle school students’ academic achievement (Altermatt & Pomerantz, 2005; Berndt & Keefe, 1995), and several mechanisms may be at play. For example, students may learn effective study skills by observing and imitating the study habits of their high-achieving friends; they may also have privileged access to valuable academic support. Also, the learning processes that take place when a student is collaborating with a high-achieving friend on an academic task may be particularly efficient if their interactions are more engaging and stimulating than they would be with average-achieving peers (A. F. Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995; Piaget, 1977).

Friends’ school engagement

Friends’ academic achievement is certainly not the only school-relevant characteristic that can play a positive role in the academic life of young adolescents. We cannot assume that all high-achieving students have the skills to structure a positive learning environment for their friends. The observed relationship between friends’ academic achievement and the change occurring in students’ own achievement can perhaps be attributed to other factors. Specifically, high-achieving friends may have high levels of engagement in school-appropriate behaviors. Behaviors that define school engagement include complying with school rules; cooperating with teachers and peers; putting effort into learning activities, assignments, and homework; participating in classroom interactions (e.g., discussions, questions); and being involved in extracurricular, school-based activities (Appleton, Christenson, & Furlong, 2008; Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004). Friends’ school engagement might exert a positive influence on students’ achievement regardless of friends’ own academic achievement, as suggested in past studies (Altermatt & Pomerantz, 2003; Ryan, 2001).

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how friends’ school engagement can affect early adolescents’ academic achievement. Students may come to internalize the positive learning goals promoted by their friends, or they may learn efficient coping skills that contribute to their academic achievement by observing their friends who are positive role models. Friends who display a high level of school engagement may also have positive attitudes about school and may provide other students with positive targets for social comparison and encouragement to adopt higher behavioral standards that translate into higher levels of academic achievement (Bandura, 1989; Wentzel, 2005). For instance, Berndt, Laychak, and Park (1990) and Voydanoff and Donnelly (1999) found that students’ school attitudes became more similar to those of their friends over time.

Students’ Individual Characteristics

A possibility that has rarely been investigated in past studies is that participants’ own characteristics may moderate their sensitivity to peer influence. Henry, Slater, and Oetting (2005) found that adolescents who were more inclined to take risks and who perceived alcohol as less harmful were more influenced by their friends’ alcohol use than were those who were less likely to take risks and who perceived alcohol as more harmful. Similar moderator effects may also apply to other personal characteristics. In general, youth who engage in problem behavior are more vulnerable to escalation of these behaviors when they form friendships with antisocial peers (Poulin, Dishion, & Haas, 1999). Conversely, it would follow that academically engaged students may be less distracted by friends who engage in problem behavior and more positively influenced by peers who also engage in school and who try to achieve high grades.

Parental monitoring

Friends’ influence does not occur in a vacuum: other elements of adolescents’ social environment should be taken into account. In particular, deficient parental monitoring is a well-known predictor of the development of antisocial peer networks (Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller, & Skinner, 1991), escalation of problem behavior, and a decrease in academic achievement (Crouter, MacDermid, McHale, & Perry-Jenkins, 1990). Parental monitoring could account for students’ academic achievement either directly by means of parents attending to the daily behavior of the child, such as completing homework and participating in other school activities, or indirectly in terms of parents gathering information about the time their child spends with friends, the time they spend unsupervised, their opportunities to develop friendships with peers who engage in problem behavior, and their opportunities to engage in problem behavior themselves (Dishion, Bullock, & Kiesner, 2008). Because time spent with parents decreases as adolescents become older (Larson & Richards, 1991), parents’ indirect monitoring has been more often examined in studies of adolescent samples. This aspect of monitoring appears to be important, because low levels of parents’ knowledge about their early adolescent's activities have been found to predict delinquency in middle adolescence, after accounting for adolescents’ earlier levels of delinquency and for parents’ active limit setting (Lahey, Van Hulle, D'Onofrio, Rodgers, & Waldman, 2008). These results suggest that it is important to account for parental monitoring when predicting early adolescents’ academic achievement.

This Study

There is some evidence that friends’ characteristics in middle school are relevant to students’ academic achievement. However, few studies have compared and contrasted the relative contribution of positive friends’ characteristics and negative friends’ characteristics to students’ academic achievement across the middle school years. This study examined two hypotheses. First, we tested the direct peer socialization hypothesis suggesting that friends’ academic achievement, school engagement, and problem behavior would each contribute to changes in participants’ academic achievement from Grade 6 through Grade 8, controlling for participants’ own characteristics and for parental monitoring. We expected that friends’ academic achievement and school engagement would enhance students’ achievement and that friends’ problem behavior would disrupt students’ achievement. Second, we tested the hypothesis that the relationship between friends’ characteristics and the change in academic achievement over the middle school years would be moderated by participants’ own characteristics. We hypothesized that students would be more susceptible to being influenced by friends who have characteristics similar to their own. A secondary goal of this study was to explore possible gender differences in these main effects and interaction effects.

Method

Participants

This sample included 1,278 participants recruited in eight middle schools in a suburban area of the northwest region of the United States. The first assessment took place when participants were in Grade 6 (mean age: 12 years and 2 months). A follow-up assessment took place in Grade 8 (mean age: 13 years and 11 months). The proportion of targeted students who participated in the study was 74%. The sample included 45.4% male participants. Participants were primarily European American (78.2%), and the minority groups included Hispanic/Latino (4.5%), American Indian (3.3%), Asian American (3.1%), Pacific Islander (1.5%), African American (1.2%), mixed ethnicity (4.7%), and other or unknown ethnicity (3.6%).

Measures

Descriptive properties of the measures used in this study are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

T-tests for Gender Differences and Descriptive Statistics for Each Variable

| T-test for gender differences | Full sample | Girls | Boys | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | t (df) | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Academic achievement (Grade 6) | –4.37 (1015) | 3.18 | .67 | 3.26 | .62 | 3.08 | .71 |

| Academic achievement (Grade 8) | –6.94 (1090) | 2.98 | .83 | 3.13 | .76 | 2.79 | .87 |

| School engagement | –7.30 (1028) | .52 | .15 | .55 | .13 | .49 | .15 |

| Problem behavior | 6.90 (1028) | .09 | .15 | .06 | .12 | .12 | .17 |

| Parental monitoring | –5.02 (1028) | .78 | .23 | .82 | .22 | .74 | .24 |

| Friends’ academic achievement | –4.10 (987) | 3.23 | .51 | 3.29 | .48 | 3.16 | .53 |

| Friends’ school engagement | –7.59 (990) | .39 | .11 | .41 | .10 | .36 | .11 |

| Friends’ problem behavior | 5.86 (990) | .10 | .12 | .08 | .11 | .12 | .13 |

Note. To preserve the scaling of the untransformed variables, these values were computed from unstandardized data. T-tests revealed that all gender differences were significant at p < .001. The school engagement, problem behavior, and parental monitoring scales were transformed to improve their distribution.

Best friendship nominations

These nominations were collected using the Social Nomination questionnaire (SONOM; Coie, Terry, Zakriski, & Lochman, 1995). Participants were provided a roster that included the names of all their grademates who agreed to participate in the study. Participants were asked to circle the names of their three best friends. The Grade 6 measures of academic achievement, school engagement, and problem behavior as described later in this section could be used to assess not only participants’ own characteristics, but also those of their participating friends. For each of these variables, we averaged the scores obtained by all nominated best friends (maximum three).

Although some researchers consider that the reciprocity of the relationship (as defined by mutual friendship nominations) is a fundamental criterion of the friendship experience (Parker, Rubin, K. H., Price, & DeRosier, 1995; Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, & Parker, 1998), others propose that children who receive unilateral (i.e., nonreciprocated) nominations can also be considered as friends of the children who nominated them. For instance, a meta-analysis by A. F. Newcomb and Bagwell (1995) revealed that unilateral friendship dyads are more engaged in their relationship and display more ability to solve their conflicts than are mere acquaintances. Furthermore, a study by Aloise-Young, Graham, and Hansen (1994) on the initiation of cigarette smoking in middle school suggests that nonreciprocated friends can be even more influential than reciprocated friends, possibly because students’ imitative behavior is an attempt to show desired friends their willingness to conform to their norms and to enter their clique. Therefore, we decided not to restrict our definition of friendship to reciprocated best friends only, and to acknowledge as a best friend all the classmates nominated by each participant (maximum three).

Academic achievement

Academic achievement was measured by using GPA from official school records for participants and their participating friends. Schools sent us the scores at the end of Grade 6 and again at the end of Grade 8. GPA scores ranged from 0.0 to 4.0.

School engagement

Behavioral engagement in school was assessed using a five-item scale included in the Student's Self-Report Survey (SSRS; Dishion & Stormshak, 2001), completed by participants and their participating friends. These items asked participants how often in the past month they had performed behaviors such as: complete my homework and assignments on time, participate in sports or another organized activity, cooperate with teachers. Participants answered on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (never, almost never) to 4 (always, almost always). The mean score on all five items was computed, so participants’ total scores for this scale ranged from 0 to 4, with a reliability of α = .73. Because students tended to score relatively high on this scale, there was a skewness issue (−1.56) and a kurtosis issue (3.28). Therefore, a logarithmic transformation was applied. After the transformation, possible values ranged from .00 to .70 (skewness = −.63; kurtosis = −.02). The descriptive properties of the transformed scale are reported in Table 1.

Problem behavior

Problem behavior was assessed in Grade 6 by using an 11-item scale included in the SSRS (Dishion & Stormshak, 2001), completed by participants and their participating friends. These items asked participants how many times in the past three months they had performed problem behaviors such as: lie to your parents about where you have been or whom you were with, intentionally hit or threaten to hit someone at school, carry or handle a weapon such as a gun or knife (not including hunting). Participants responded on a six-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (more than 20 times). This measure also included one item that assesses the frequency of cigarette use in the past month by using a six-point scale ranging from 0 (none) to 5 (11 or more packs), and one item that assesses the frequency of alcohol use in the past month by using a six-point scale ranging from 0 (none) to 5 (11 or more drinks). The mean score on all items was computed, so participants’ total scores for this scale ranged from 0 to 5, with a reliability of α = .83 Because students tended to score relatively low on this scale, there was a skewness issue (4.24) and a kurtosis issue (23.36). Consequently, an inverse transformation was applied. After the transformation, possible values ranged from .00 to .74 (skewness = 1.79; kurtosis = 3.32). The descriptive properties of the transformed scale are reported in Table 1.

Parental monitoring

Parents’ monitoring of their child's activities was assessed using a four-item scale included in the SSRS (Dishion & Stormshak, 2001), completed by participants. These items asked the participants how often during the past three months did at least one of their parents: know what [the participant] was doing when [he/she] was away from home; know where [the participant] was after school; have a pretty good idea about [the participant's] plans for the coming day; have a pretty good idea about [the participant's] interests, activities, and whereabouts. Participants answered on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (never, almost never) to 4 (always, almost always). The mean score on all four items was computed, so participants’ total scores of this scale ranged from 0 to 4, with a reliability of α = .82. Because students tended to score relatively high on this scale, there was a skewness issue (−2.35) and a kurtosis issue (6.86). Therefore, an inverse transformation was applied to this scale. After the transformation, possible values ranged from 0.20 to 1.00 (skewness = −.52; kurtosis = −.75). The descriptive properties of the transformed scale are reported in Table 1.

Procedure

We sent a consent form providing information about the study to the parents (or guardians) of potential participants through the schools whose principals had approved our study. Students and their parents were asked to sign and return the form to the school. Research assistants explained the study and administered the questionnaires to groups of participating students in the classroom setting. Teachers were asked to leave the room, and participants were informed of the confidential nature of their data. Each participant was paid $30 for completing the survey.

Results

Analytic Strategy

Because several interaction effects were of interest in this study, a hierarchical linear regression framework, including main effects and interaction terms, was adopted. To facilitate the interpretation of interaction effects, all predictor variables were standardized prior to being included in the analysis.

Analysis and Treatment of Missing Data

We reached different levels of completion for different measures. For the outcome variable (academic achievement in Grade 8), we had complete data for 85.5% of participants. For all student-reported variables in Grade 6 (i.e., problem behavior, school engagement, and parental monitoring), we had complete data for 80.6% of our sample. We obtained academic achievement data from school records of students’ GPA in Grade 6 for 79.6% of our participants. We computed an average score of friends’ academic achievement for 77.4% of our participants. We computed an average score of friends’ school engagement and problem behavior for 77.6% of our participants. Overall, 65.8% of participants had complete data on all our measures. A series of t-tests revealed significant differences between participants who had some missing data and those who did not, the latter presenting an overall better adjustment. However, no significant differences emerged for parental monitoring, friends’ problem behavior, and gender.

Assuming that values were missing at random (MAR), the use of multiple imputations (Allison, 2001) was an adequate method to deal with missingness. Missing data were imputed using the fully conditional specification method, which is an iterative Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method available from the multiple imputations module in SPSS 17.0.0. We created five full datasets and ran our analyses on each of these. The SPSS multiple imputations module was used to combine the parameter estimates and corresponding standard errors obtained for each of the five datasets to yield pooled estimates and inferential statistics using D. B. Rubin's (1987) method.

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents the results of t-tests performed on each measure to detect gender differences, which were significant for all measures. Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations not only for the full sample, but also for girls and for boys separately.

Table 2 presents correlations among all study variables. All the variables included in this study were significantly correlated at p < .001 in the expected direction.

Table 2.

Correlations Among All Study Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Academic achievement (Grade 6) | — | .55 | .36 | –.21 | .23 | .42 | .15 | –.18 | .14 |

| 2. Academic achievement (Grade 8) | .56 | — | .41 | –.33 | .30 | .27 | .22 | –.29 | .21 |

| 3. School engagement | .38 | .41 | — | –.41 | .45 | .18 | .31 | –.28 | .22 |

| 4. Problem behavior | –.23 | –.35 | –.41 | — | –.51 | –.17 | –.25 | .28 | –.21 |

| 5. Parental monitoring | .24 | .30 | .45 | –.51 | — | .15 | .16 | –.21 | .16 |

| 6. Friends’ academic achievement | .41 | .27 | .19 | –.18 | .17 | — | .34 | –.20 | .13 |

| 7. Friends’ school engagement | .16 | .23 | .31 | –.25 | .17 | .33 | — | –.48 | .23 |

| 8. Friends’ problem behavior | –.20 | –.28 | –.29 | .30 | –.24 | –.21 | –.47 | — | –.18 |

| 9. Gender | .13 | .20 | .21 | –.20 | .14 | .12 | .22 | –.17 | — |

Note. All correlations are significant at the p < .001 level. For Gender, boys are coded 0 and girls are coded 1. Above the diagonal: correlations based on original, nonimputed values (pairwise deletion). Below the diagonal: pooled estimates of correlations computed on the five imputed datasets.

Primary Analyses

The dependent variable for all regression analyses was academic achievement in Grade 8, and all predictors and control variables were measured in Grade 6.

Hypothesis 1: Main effects of friends’ characteristics

In the first step, we entered participants’ initial level of academic achievement, their gender, and their levels of school engagement, problem behavior, and parental monitoring, all measured in Grade 6. All these variables were significant predictors of academic achievement in Grade 8 in the expected direction, except for parental monitoring, which was nonsignificant.

In the next step, we entered the three measures of friends’ characteristics: academic achievement, school engagement, and problem behavior. Results of the regression model at this step are presented in Table 3. The parameters associated with the predictors entered in the previous step remained essentially the same. Because all variables were standardized, the unstandardized coefficients (B) that are reported in Table 3 can be interpreted as standardized coefficients (β). The magnitude of the effect associated with each variable can be interpreted using Cohen's (1988) cut-off values for small, medium, and large effect sizes, which are .10, .30, and .50, respectively. To test for gender differences in the relationship between friends’ characteristics and change in academic achievement, we entered in an additional step the interaction terms involving gender and each of the friends’ characteristics. None of these gender interactions was statistically significant.

Table 3.

Test of the Main Effects of Friends’ Characteristics.

| Variable | B | SE B | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | –.001 | .02 | .03 |

| Academic achievement | .46 | .03 | 13.96*** |

| Gender | .07 | .03 | 2.25* |

| School engagement | .12 | .03 | 3.48*** |

| Problem behavior | –.14 | .03 | –3.97*** |

| Parental monitoring | .05 | .04 | 1.28 |

| Friends’ academic achievement | –.01 | .03 | –.25 |

| Friends’ school engagement | .04 | .03 | 1.14 |

| Friends’ problem behavior | –.08 | .04 | –2.12* |

Note. R2 = .40. This table presents pooled estimates of the hierarchical linear regressions run on the five imputed datasets to predict academic achievement in Grade 8 from Grade 6 predictors. For Gender, boys are coded 0 and girls are coded 1. All variables were standardized.

p < .05

p < .001.

Table 3 shows that participants’ academic achievement in Grade 6 is the most powerful predictor of academic achievement in Grade 8, with an effect size approaching large amplitude. Individual characteristics were significant predictors of change in academic achievement from Grade 6 through Grade 8. Participants’ problem behavior predicted lower achievement and participants’ school engagement predicted higher achievement than expected, and both variables made about equal contributions within the small range. Gender had a smaller but significant effect on academic achievement, with girls obtaining higher grades in Grade 8 than boys, after controlling for achievement in Grade 6. Parental monitoring did not contribute to changes in academic achievement beyond the contribution of individual characteristics.

Of particular importance in the context of this study, Table 3 shows that only friends’ problem behavior was a significant predictor of a negative change in participants’ academic achievement when the three measures of friends’ characteristics were entered simultaneously. Additional analyses showed that friends’ school engagement was a significant predictor of a positive change in participants’ academic achievement when the other two measures of friends’ characteristics were not entered in the model, B = .07, SE = .03, p < .01 (not presented in Table 3), and this main effect was marginally significant after adding other interactions terms in the model, as described later under Hypothesis 2: Interactions between participants’ characteristics and friends’ characteristics. In the main effect model, friends’ academic achievement did not predict change in participants’ own academic achievement, even when it was the only measure of friends’ characteristics entered in the model.

Hypothesis 2: Interactions between participants’ characteristics and friends’ characteristics

To test our hypothesis that there could be interactions between participants’ own characteristics and their friends’ characteristics, we included all the main effects previously presented and further added two-way interactions involving each of the participants’ characteristics (academic achievement, school engagement, problem behavior) multiplied by each of the friends’ characteristics.

The first subset of interactions included those based on participants’ academic achievement and the three measures of friends’ characteristics. The pooled regression coefficients for the interaction between participants’ academic achievement and their friends’ academic achievement was significant, B = .06, SE = .03, p < .05, and was retained for further analyses. The interactions involving friends’ problem behavior and school engagement were not significant.

A second subset comprising the three interactions based on participants’ problem behavior was then entered, but none of its components was significant. Similarly, none of the interactions included in the third subset, based on participants’ school engagement, was significant.

Follow-up analyses explored gender differences in the interaction between participants’ characteristics and friends’ characteristics, and revealed that the interaction between participants’ academic achievement and their friends’ achievement, identified in the previous step, differed across genders. Table 4 presents the results of our final model, including all main effects; the three-way interaction involving participants’ academic achievement, friends’ academic achievement, and gender; and all lower order, two-way interactions. Because all variables were standardized, the unstandardized regression coefficients (B) that are reported can be interpreted as standardized coefficients (β).

Table 4.

Test of the Interaction Between Participants’ Academic Achievement, Friends’ Academic Achievement, and Gender

| Variable | B | SE B | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | –.02 | .03 | –.64 |

| Academic achievement | .47 | .03 | 13.91*** |

| Gender | .04 | .03 | 1.20 |

| School engagement | .13 | .03 | 3.36*** |

| Problem behavior | –.13 | .04 | –3.73*** |

| Parental monitoring | .05 | .04 | 1.33 |

| Friends’ academic achievement | –.02 | .03 | –.58 |

| Friends’ school engagement | .06 | .03 | 1.72† |

| Friends’ problem behavior | –.07 | .04 | –1.83† |

| Academic Achievement × Friends’ Academic Achievement | .07 | .03 | 2.71* |

| Gender × Friends’ Academic Achievement | –.05 | .03 | –1.63 |

| Gender × Academic Achievement | –.03 | .03 | –.98 |

| Gender × Academic Achievement × Friends’ Academic Achievement | .06 | .02 | 2.89** |

Note. R2 = .41. This table presents pooled estimates of the hierarchical linear regressions run on the five imputed datasets to predict academic achievement in Grade 8 from Grade 6 predictors. For Gender, boys are coded 0 and girls are coded 1. All variables were standardized.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

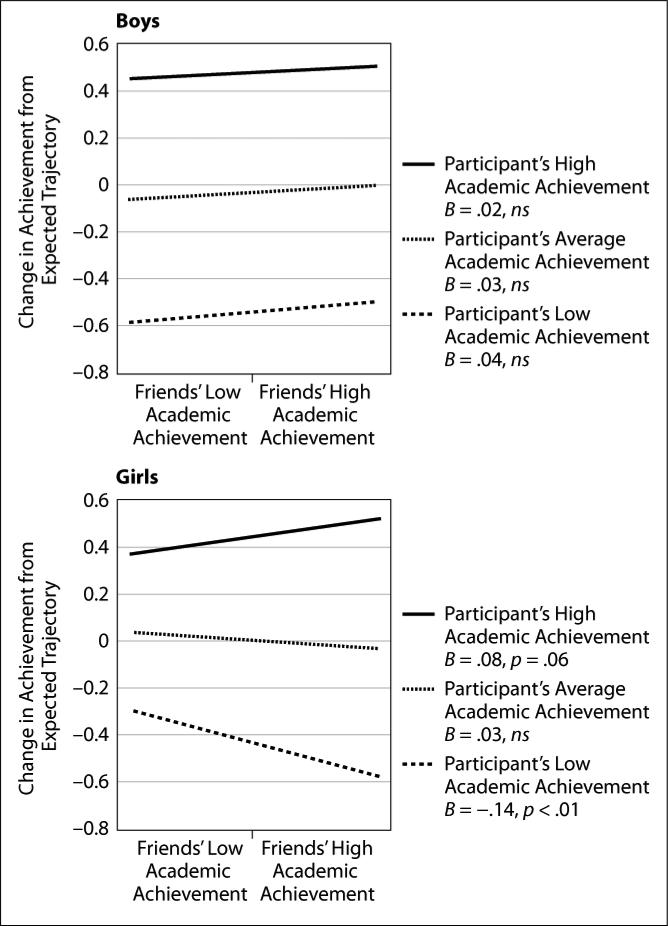

Figure 1 presents a decomposition of the significant interaction effect (Gender × Participants’ Academic Achievement × Friends’ Academic Achievement). In this figure, low and high levels of academic achievement were operationalized as one standard deviation below and above the mean, respectively. The y axis represents a relative measure of expected change in academic achievement by Grade 8, with 0 representing no change from the expected trajectory, positive values representing higher achievement than expected, and negative values representing lower achievement than expected. The upper panel shows that boys’ academic achievement in Grade 6 is a consistent predictor of achievement in Grade 8, regardless of boys’ associations with high-achieving or low-achieving friends. In contrast, the lower panel shows that although girls’ academic achievement in Grade 8 is also consistently predicted by their achievement in Grade 6, their association with higher or lower achieving friends also plays a role. For girls who were high achievers in Grade 6, having high-achieving friends contributed to a greater increase in academic achievement relative to their expected trajectory, as revealed by a marginally significant positive slope. Friends’ academic achievement did not influence the expected change in girls’ academic achievement when their own achievement was average. For girls who were low achievers in Grade 6, however, having high-achieving friends was related to lower academic achievement than expected in Grade 8, as revealed by a significant negative slope.

Figure 1.

Interaction between participants’ own level of academic achievement and their friends’ academic achievement in predicting changes in academic achievement by Grade 8 (controlling for achievement in Grade 6), for boys (top panel) and girls (bottom panel).

Discussion

The first goal of this study was to test for the hypothesis that socialization processes among friends contribute to early adolescents’ academic achievement by evaluating the main effects of friends’ academic achievement, school engagement, and problem behavior. The second goal was to verify if students’ individual characteristics (initial levels of academic achievement, school engagement, and problem behavior) would moderate the influence of friends’ characteristics on changes in academic achievement across middle school years.

Friends’ Characteristics

We found partial support for our hypothesis that friends’ characteristics show unique effects on participants’ academic achievement by the end of Grade 8, after accounting for previous levels of academic achievement in Grade 6. In fact, in line with results obtained by Vitaro et al. (2005), friends’ problem behavior contributed to a greater decrease in academic achievement than expected from Grade 6 through Grade 8 within a main-effect model, and it remained marginally significant in the final model that included interaction effects. Although the magnitude of the effect was small, it held even when controlling for participants’ own levels of problem behavior, other school-related characteristics, and parental monitoring.

The association between friends’ problem behavior and a student's lower academic achievement could be mediated by increased accessibility to deviant activities that impede on or replace the student's engagement in classes as well as homework. Friends engaging in problem behavior, which often offers immediate rewards (e.g., excitement inherent to forbidden activities), are likely to reinforce behaviors and attitudes that are detrimental to the development of emotional and psychological conditions (including self-regulation) that facilitate the attainment of long-term goals (e.g., preparing for high school and college; M. D. Newcomb et al., 2002; Wentzel, 1993). In other studies, analyses of videotaped interactions occurring within dyads of adolescent friends showed that conversations characterized by deviant content, along with friends’ reinforcement for deviant talk, predicted increases in youths’ deviant behaviors, with early adolescence being the key developmental period for peer influence (Dishion & Nelson, 2007; Dishion, Nelson, Winter, & Bullock, 2004).

The compensatory effect of friends’ school engagement did not emerge in our main effect model that included other friends’ characteristics, but it was significant when entered in the model by itself, without the inclusion of other friends’ characteristics, and it was marginally significant in the final model. This result is especially interesting in the context of our study, because we found a detrimental effect of friends’ academic achievement for low-achieving girls (discussed in greater detail later in this section). It seems that having friends who directly model the behaviors that are usually conducive to positive adjustment in the school setting (e.g., completing school work, cooperating with other people in the school setting) is more important than having friends who achieve high grades.

Together, these findings may imply that peer socialization processes that promote academic achievement during the middle school years do not involve specific study behaviors that are found in high-achieving students, but rather are explained by friends’ tendency to refrain from engaging in deviant behaviors and by their tendency to actively engage in positive school-related behaviors. For example, the time that students spend with their well-adjusted friends on studying and completing assignments cannot be spent on joyriding, vandalizing, or drinking alcohol. We can even speculate that the specific activities in which prosocial youngsters are engaged might not be as important as the simple fact that they are too busy to engage in problem behaviors.

Our findings suggest that school-based policies that encourage the aggregation of antisocial students in special classrooms or in behavioral intervention programs is problematic not only because it appears to contribute to escalating patterns of problem behavior (e.g., Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999; Dodge, Dishion, & Lansford, 2006), but also because it might precipitate school failure. Revising school policies, for example by guiding these adolescents toward adult-supervised extracurricular activities with well-adjusted peers, could help prevent school failure (Battin-Pearson et al., 2000; Vitaro, Larocque, Janosz, & Tremblay, 2001).

Also, as children make new friends in their new school, they are exposed to older peers who have easier access to substances and to situations that facilitate antisocial activities that may appear attractive and exciting to younger students. Parents, who may be tempted to help their teenagers be autonomous and let them choose their own friends, should still make efforts to get to know those friends, for example by asking school staff to share information about their children's schoolmates. Parents should keep in mind that extracurricular activities that are school based and supervised by adults are a good way for children to meet other friends who enact prosocial behaviors and who have a healthy school connection (B. L. Barber, Stone, Hunt, & Eccles, 2005).

Moderation Effect of Students’ Academic Achievement

We found a significant interaction effect between participants’ own academic achievement and their friends’ academic achievement, but only among girls. On the one hand, and in line with Kandel's (1978) definition of socialization processes, high-achieving girls who had similarly high-achieving friends in Grade 6 appeared to socialize each other into working hard in school and reaching even higher levels of achievement than expected two years later. On the contrary, having high-achieving friends predicted a lower level of academic achievement than expected for low-achieving girls. The social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954) can help explain these results; it suggests that upward comparison to outperforming peers can lead to a negative self-evaluation, which in turn can translate into lower self-efficacy and performance.

To reconcile the different findings for high- versus low-achieving girls, Lockwood and Kunda (1997) offer a hypothesis. Their findings suggest that an individual's perception of a peer's performance as either attainable or unattainable moderates the social comparison process and its impact on self-evaluation and motivation. When one perceives the performance of a high-achieving individual as within one's reach—which would be the case for students who already do well in school—then upward social comparison can motivate the student to adopt high goals. On the other hand, when friends’ high performance seems out of reach—as may be the case for low-achieving students—then upward social comparison can be detrimental to one's self-perception. Because school friends are easy targets for social comparison of one's academic achievement, having high-achieving friends can be expected to have a significant impact, either negative or positive, on students’ self-evaluation, self-efficacy, and academic achievement.

In line with this moderation model, Altermatt and Pomerantz (2005) found that low-achieving students in Grades 5–7 who had high-achieving friends displayed a greater decrease in self-evaluation, but a greater increase in academic achievement, than did those who had low-achieving friends. The authors speculate that an enduring pattern of negative self-assessment based on social comparison could eventually affect students’ academic self-efficacy and be detrimental to their academic achievement, which is consistent with our findings for slightly older students. This suggests that school staff should be sensitive to the psychological distress that low-achieving girls may experience. Schools should provide numerous ways for all students to achieve positive self-esteem, such as praising students’ progress relative to their own previous levels of achievement and minimizing comparisons among different students.

The lack of association between friends’ academic achievement and changes in boys’ own academic achievement is consistent with Rose and Rudolph's (2006) peer-socialization model stating that girls have a greater need for social approval than do boys, which can create vulnerability to internalizing problems. Girls may be more sensitive to their friends’ norms for academic success and suffer a decrease in self-esteem and self-efficacy when they are unable to reach those standards. In support of this hypothesis, Lahaderne and Jackson (1970) found that girls with lower IQ presented a particularly high need for social desirability, to the detriment of their investment in productive school behaviors, but these results did not hold for boys.

Other Predictors

Other predictors included for control purposes deserve some attention. As expected, academic achievement in Grade 6 was a strong predictor of this same variable in Grade 8. We also found that participants with lower school engagement and those who engage in problem behaviors are likely to achieve at lower levels during those academic years. Although parental monitoring did not directly predict changes in academic achievement over the course of middle school, it was strongly correlated with youth problem behavior at the point of school entry, thus suggesting an indirect effect. Previous research has shown that parenting interventions that target parental monitoring can reduce problem behavior, and that effects on problem behavior are mediated by changes in parental monitoring (Dishion, Nelson, & Kavanagh, 2004). Therefore, when youth are engaged in high levels of problem behavior in the first year of middle school, it is critical to support parents and teachers in behavior management practices that address and effectively reduce the behavior, while promoting students’ engagement in the achievement process.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. Its large sample size provided statistical power to detect small effects and to assess all relevant interactions. The longitudinal data spanning the entire middle school period made it possible to capture changes occurring during a crucial time of development. Availability of friends’ own reports of their problem behavior and school engagement and of the friends’ official school records represents an improvement over participants’ own reports about their friends, which inflate the level of similarity between friends (Prinstein & Wang, 2005). The inclusion of initial levels of participants’ own characteristics in the model helped us perform a valid test of socialization processes. The inclusion of several friends’ characteristics also helped disentangle the relative contribution of correlated factors. Furthermore, the use of multiple imputations to account for missing values helped us obtain more trustworthy results than would the typical strategies used for regression analyses.

Nevertheless, this study presents some limitations. Although parental knowledge of their early adolescents’ activities, which we measured in this study, is one important aspect of parenting (Lahey et al., 2008), Kerr and Stattin (2000) suggest that a more thorough understanding of the effects of parental monitoring on early adolescents’ development may be achieved by investigating the family processes that protect young adolescents against negative outcomes such as academic failure (e.g., creating a safe climate at home that encourages communication and attachment to the family).

Another limitation of our measures is that we predicted change in academic achievement between Grade 6 and Grade 8 from friends’ characteristics in Grade 6 without controlling for the more proximal predictor of friends’ characteristics in Grade 8. If we could confirm that our results hold even after including a measure of friends’ characteristics in Grade 8, we would have provided a stronger test of our hypothesis that early middle school friendships contribute to setting students on either a positive or a negative path with regard to their future academic achievement. Also, because this sample was recruited at middle school entry, we cannot exclude the possibility that potential socialization effects among friends had been happening prior to the middle school years. Neither can we exclude the possibility that other preexisting, unmeasured individual factors (e.g., students’ future orientation, perceived importance of school, attachment to school, intelligence) or familial factors (socioeconomic status, parents’ encouragement of education, parents’ education and ability to help their children with schoolwork) explain our results.

In addition, this sample was recruited from a predominantly European American community, so it was impossible to assess whether these findings generalize to small ethnic minority groups. Furthermore, because friends’ characteristics were assessed as the average score obtained by participants nominating a maximum of three peers as their best friends, further investigations should explore whether the contribution of friends’ characteristics would be the same if we had used a more stringent definition of friendship (e.g., mutual friendship nominations) or a less stringent one (e.g., unlimited nominations, all members of one's clique), or if we had measured the composition of students’ complete friendship network (e.g., the proportion of deviant friends or the proportion of well-adjusted friends in the network). Also, out-of-school friends may have a meaningful influence, but they were not included in this study. Similarly, further research is needed to verify whether the observed role of friends’ characteristics interacts with the characteristics of the relationship itself (e.g., friendship quality or reciprocity). Last, the nonexperimental nature of this study makes it impossible to draw causal inferences, and any reference to the “influence” or to the “effects” of friends’ characteristics in this article should be interpreted with caution.

Concluding Remarks

This study contributed to a better understanding of the peer relationships that can affect early adolescents’ academic achievement during the middle school years. Affiliating with friends who engaged in problem behavior in Grade 6 was associated with a lower level of academic achievement than expected by the end of Grade 8, even after controlling for important variables. Affiliating with highly engaged friends in Grade 6 seemed to compensate for the negative effect associated with friends who display problem behavior, although some inconsistency across models warrants further research. Affiliating with high-achieving friends was detrimental for low-achieving girls, but it appeared to be beneficial for high-achieving girls, and it was irrelevant for boys. To promote academic success in middle school, responsible adults should pay special attention to changes in friendship affiliations upon the transition to middle school and encourage early adolescents to participate in supervised activities during which they can become friends with prosocial peers instead of antisocial ones.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this manuscript was made possible by a postdoctoral fellowship awarded to Marie-Hélène Véronneau by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and by grants DA 07031 and DA 13773 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health to Thomas J. Dishion. We acknowledge the contribution of The Next Generation staff (Peggy Veltman, Trina McCartney, Barb Berry, Carole Dorham, and Nancy Weisel), Eugene School District 4J, 4J Counselor Anne McRae, and the participating youth and families. We also wish to acknowledge Cheryl Mikkola for her editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript, and John Seeley and Jeff Gau for statistical consultations.

References

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR, Kabbani NS. The dropout process in life course perspective: Early risk factors at home and school. Teachers College Record. 2001;103(5):760–822. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data. Sage publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Aloise-Young PA, Graham JW, Hansen WB. Peer influence on smoking initiation during early adolescence: A comparison of group members and group outsiders. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1994;79(2):281–287. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.79.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alspaugh JW. Achievement loss associated with the transition to middle school and high school. Journal of Educational Research. 1998;92(1):20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Altermatt ER, Pomerantz EM. The development of competence-related and motivational beliefs: An investigation of similarity and influence among friends. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95(1):111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Altermatt ER, Pomerantz EM. The implications of having high-achieving versus low-achieving friends: A longitudinal analysis. Social Development. 2005;14(1):61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton JJ, Christenson SL, Furlong MJ. Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychology in the Schools. 2008;45(5):369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory. In: Vasta R, editor. Annals of child development: Vol. 6. Six theories of child development. JAI Press; Greenwich, CT: 1989. pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Olsen JA. Assessing the transitions to middle and high school. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19(1):3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BL, Stone MR, Hunt JE, Eccles JS. Benefits of activity participation: The roles of identity affirmation and peer group norm sharing. In: Mahoney JL, Larson RW, Eccles JS, editors. Organized activities as contexts of development: Extracurricular activities, after-school and community programs. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah: 2005. pp. 185–210. [Google Scholar]

- Battin-Pearson S, Newcomb MD, Abbott RD, Hill KG, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. Predictors of early high school dropout: A test of five theories. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2000;92(3):568–582. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ, Keefe K. Friends’ influence on adolescents’ adjustment to school. Child Development. 1995;66(5):1312–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ, Laychak AE, Park K. Friends’ influence on adolescents’ academic achievement motivation: An experimental study. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1990;82(4):664–670. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann C, Dalton B. Interpersonal influences and educational aspirations in 12 countries: The importance of institutional context. Sociology of Education. 2002;75(2):99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Terry R, Zakriski A, Lochman J. Early adolescent social influences on delinquent behavior. In: McCord J, editor. Coercion and punishment in long-term perspectives. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1995. pp. 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, MacDermid SM, McHale SM, Perry-Jenkins M. Parental monitoring and perceptions of children's school performance and conduct in dual- and single-earner families. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26(4):649–657. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Bullock BM, Kiesner J. Vicissitudes of parenting adolescents: Daily variations in parental monitoring and the early emergence of drug use. In: Kerr M, Stattin H, Engels RCME, editors. What can parents do? New insights into the role of parents in adolescent problem behavior. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; Chichester, England: 2008. pp. 113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist. 1999;54(9):755–764. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE. Male adolescent friendships: Relationship dynamics that predict adult adjustment. In: Engels R, Kerr M, Stattin H, editors. Friends, lovers and groups: Key relationships in adolescence. Wiley; New York: 2007. pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Bullock BM. Premature adolescent autonomy: Parent disengagement and deviant peer process in the amplification of problem behaviour. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27(5):515–530. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Kavanagh K. The Family Check-Up with high-risk young adolescents: Preventing early-onset substance use by parent monitoring. Behavior Therapy. 2003;34(4):553–571. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Winter CE, Bullock BM. Adolescent friendship as a dynamic system: Entropy and deviance in the etiology and course of male antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(6):651–663. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000047213.31812.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M, Skinner ML. Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27(1):172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA. Student Self-report Survey. Child and Family Center, University of Oregon; 2001. Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE. Deviant peer influences in programs for youth: Problems and solutions. Guilford; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Lord S, Buchanan CM. School transitions in early adolescence: What are we doing to our young people? In: Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen AC, editors. Transitions through adolescence: Interpersonal domains and context. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1996. pp. 251–284. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations. 1954;7:117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Finn JD. Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research. 1989;59(2):117–142. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research. 2004;74(1):59–109. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W. Children's friendships. In: Field TM, editor. Review of human development. Wiley; New York: 1982. pp. 327–339. [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, Slater MD, Oetting ER. Alcohol use in early adolescence: The effect of changes in risk taking, perceived harm and friends’ alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(2):275–283. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW. The company they keep: Friendships and their developmental significance. Child Development. 1996;67(1):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Homophily, selection, and socialization in adolescent friendships. American Journal of Sociology. 1978;84(2):427–436. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahaderne HM, Jackson PW. Withdrawal in the classroom: A note on some educational correlates of social desirability among school children. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1970;61(2):97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Van Hulle CA, D'Onofrio BM, Rodgers JL, Waldman ID. Is parental knowledge of their adolescent offspring's whereabouts and peer associations spuriously associated with offspring delinquency? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36(6):807–823. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9214-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Richards MH. Daily companionship in late childhood and early adolescence: Changing developmental contexts. Child Development. 1991;62(2):284–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood P, Kunda Z. Superstars and me: Predicting the impact of role models on the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73(1):91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Khoo S-T. Longitudinal studies of achievement growth using latent variable modeling. Learning and Individual Differences. 1998;10(2):73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb AF, Bagwell CL. Children's friendship relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(2):306–347. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Abbott RD, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Battin-Pearson S, Hill K. Mediational and deviance theories of late high school failure: Process roles of structural strains, academic competence, and general versus specific problem behaviors. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2002;49(2):172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Paikoff RL, Brooks-Gunn J. Do parent–child relationships change during puberty? Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110(1):47–66. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Rubin KH, Price JM, DeRosier ME. Peer relationships, child development, and adjustment: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 2. Risk, disorder, and adaptation. Wiley; New York: 1995. pp. 96–161. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Orderly change in a stable world: The antisocial trait as a chimera. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(6):911–919. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial boys. Castalia; Eugene, OR: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. In: La Naissance de l'intelligence chez l'enfant [Origin of intelligence in the child] Neuvième, editor. Delachaux et Niestlé; Paris: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Poulin F, Dishion TJ, Haas E. The peer influence paradox: Friendship quality and deviancy training within male adolescent friendships. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1999;45(1):42–61. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Wang SS. False consensus and adolescent peer contagion: Examining discrepancies between perceptions and actual reported levels of friends’ deviant and health risk behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33(3):293–306. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz E, Dekovic M, Meijer AM, Engels RCME. Longitudinal relations among parenting, best friends, and early adolescent problem behavior: Testing bidirectional effects. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2006;26(3):272–295. [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(1):98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, Slater MD, Oetting ER. Alcohol use in early adolescence: The effect of changes in risk taking, perceived harm and friends’ alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(2):275–283. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Bukowski W, Parker JG. Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In: Damon W, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 5th ed. Wiley; New York: 1998. pp. 619–700. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan AM. The peer group as a context for the development of young adolescent motivation and achievement. Child Development. 2001;72(4):1135–1150. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Brendgen M, Wanner B. Patterns of affiliation with delinquent friends during late childhood and early adolescence: Correlates and consequences. Social Development. 2005;14(1):82–108. [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Larocque D, Janosz M, Tremblay RE. Negative social experiences and dropping out of school. Educational Psychology. 2001;21(4):401–415. [Google Scholar]

- Voydanoff P, Donnelly BW. Risk and protective factors for psychological adjustment and grades among adolescents. Journal of Family Issues. 1999;20(3):328–349. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Does being good make the grade? Social behavior and academic competence in middle school. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1993;85(2):357–364. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Peer relationships, motivation, and academic performance at school. In: Elliot AJ, Dweck CS, editors. Handbook of competence and motivation. Guilford; New York: 2005. pp. 279–296. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley ME, Kol KL, Bowen GL. The social context of school success for Latino middle school students: Direct and indirect influences of teachers, family, and friends. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29(1):43–70. [Google Scholar]