Abstract

Integrins have become key targets for molecular imaging and for selective delivery of anti-cancer agents. Here we review recent work concerning the targeted delivery of antisense and siRNA oligonucleotides via integrins. A variety of approaches have been used to link oligonucleotides to ligands capable of binding integrins with high specificity and affinity. This includes direct chemical conjugation, incorporating oligonucleotides into lipoplexes, and use of various polymeric nanocarriers including dendrimers. The ligand-oligonucleotide conjugate or complex associates selectively with the integrin, followed by internalization into endosomes and trafficking through subcellular compartments. Escape of antisense or siRNA from the endosome to the cytosol and nucleus may come about through endogenous trafficking mechanisms, or because of membrane disrupting capabilities built into the conjugate or complex. Thus a variety of useful strategies are available for using integrins to enhance the pharmacological efficacy of therapeutic oligonucleotides.

Keywords: Gene therapy, Integrin, RGD peptides, Antisense and siRNA oligonucleotides, Endosome escape.

The value of integrins for the delivery of antisense and siRNA oligonucleotides

Therapy with oligonucleotides: the delivery issue. Antisense and siRNA oligonucleotides have tremendous potential as therapeutic agents in cancer and other diseases. However, despite recent advances in oligonucleotide chemistry and pharmacology 1-3, the effective delivery of these molecules to their intracellular sites of action within tissues remains a key impediment to progress 4. Antisense oligonucleotides usually act via selective degradation of complementary pre-mRNA through recruitment the nuclear enzyme RNase H, while siRNA loads on to the cytoplasmic RISC complex to monitor and ultimately degrade fully complementary mRNA; thus both antisense and siRNA provide powerful means for down-regulation of gene expression 5-6. Additionally, antisense molecules can be used to shift patterns of pre-mRNA splicing 7, or to regulate gene expression via antagonizing miRNA 8. All of this can be done effectively in cell culture via potent transfection agents such as cationic lipids or polymers. However, because of toxicity issues, these approaches are sometimes not readily adapted to the in vivo situation. Thus much of the animal experimentation and clinical investigation to date using antisense or siRNA have been done with oligonucleotides administered in 'free' form, without any transfection reagent 6, 9. However, although there has been much progress, many researchers in the oligonucleotide therapeutics field believe that the efficacy of antisense or siRNA could be substantially enhanced by use of appropriate delivery systems 10-11. Recent investigations from our laboratory 12-13 and others 11, 14 have stressed the value of using various forms of receptor-mediated endocytosis as an cell entry pathway for oligonucleotides. Via this general approach, substantial increases in cellular uptake, intracellular delivery, and pharmacological effects have been attained.

Integrins as targets for oligonucleotide delivery. Members of the integrin family of cell surface adhesion receptors seem particularly attractive target for enhancing the efficiency and selectivity of delivery of antisense and siRNA oligonucleotides. The integrins are a family of heterodimeric cell surface receptors that have important roles during development and in the adult organism 15. One of the major function of integrins is to provide mechanical transmembrane linkages between extracellular matrix proteins such as fibronectin, collagen and laminin and the actin cytoskeleton 16. Integrins also play an important role in regulating several signal transduction pathways 17-19. In particular, our laboratory has explored the connection between integrins and the Erk MAP kinase mitogenic pathway 20-22. A number of integrins are differentially expressed between tumors and normal tissue 23-24, with the integrin αvβ3 being of particular interest in this context since it is highly expressed in angiogenic endothelia and in some types of tumor cells 25-26. It is known that integrins are recycled via endocytotic processes 27-31; thus the αvβ3 integrin is thought to be primarily internalized via caveolae and/or lipid raft-rich vesicles 32-33. A number of integrins, including αvβ3, then traffic through the Rab 11 positive perinuclear recycling compartment prior to returning to the cell surface 29, 34-35. Thus integrins are relatively abundantly expressed (typically ~105 copies per cell), are efficiently internalized by endocytosis, and some members of this family are differentially expressed on tumor cells; in aggregate these characteristics suggest that targeting integrins could be an excellent approach for delivery of therapeutic oligonucleotides.

Direct conjugates between oligonucleotides and integrin targeting ligands

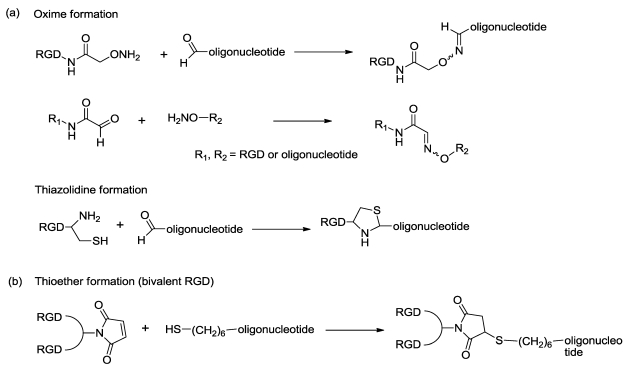

Direct conjugation of functional agents such as cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) to oligonucleotides allows enhanced cellular uptake 36; thus direct conjugation strategies have an important position in drug delivery approaches. Because many integrin ligands, including RGD, are peptides, the conjugation techniques for CPPs should be applicable to conjugation of integrin ligands. A typical approach 37 for conjugation is formation of stable chemical bonds with reactive groups in both molecules, such as thioether, disulfide, amide, oxime and hydrazone. Recently, a technique with click chemistry 38-39 has been also developed. Up to now, there are only a few reports of direct conjugation of integrin ligands to oligonucleotides. Defrancq and colleagues 40-45 have reported on various conjugates with linkages of thiazolidine and oxime. An oligonucleotide with an aldehyde moiety was coupled to RGD bearing a cysteine residue for thiazolidine formation, and an aminooxy group for oxime formation (and vice versa) (Fig 1, a). These effectively reacted without a protection strategy and under mild aqueous conditions. We also reported a direct conjugation of a bivalent-RGD that had a strong binding affinity to integrin receptors 13. The bivalent-RGD conjugated oligonucleotide was successfully synthesized by formation of a thioether linkage with a maleimide group in the bivalent-RGD and a thiol group introduced into the 5'-terminal of the oligonucleotide (Fig 1, b). Thus, this strategy, which directly conjugates integrin ligand to oligonucleotide, has a great advantage from the viewpoint of simplified synthesis.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of RGD-conjugated oligonucleotides.

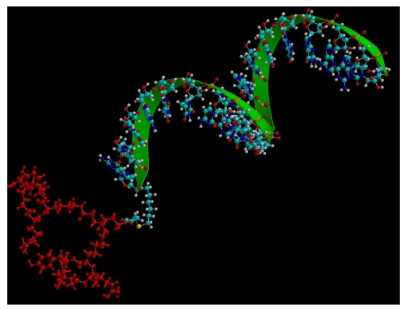

In our hands integrin-RGD conjugates have been a valuable tool for oligonucleotide delivery. Thus we used a bivalent form of RGD to target an antisense oligonucleotide to αvβ3-expressing human melanoma cells 13 (Fig 2). This oligonucleotide was designed to correct splicing of a luciferase reporter cassette that contained an aberrant intron, thus up-regulating luciferase expression and providing a positive read-out for oligonucleotide delivery. The RGD-oligonucleotide produced a several-fold enhancement of effect as compared to unmodified antisense. The mechanism of uptake seemed to track the caveolar uptake pathway known for the αvβ3 integrin, while eventually some oligonucleotide was delivered to the trans-Golgi. Recent work has suggested that the RGD—oligonucleotide and the unmodified oligonucleotide enter cells by completely different endocytotic pathways 46.

Figure 2.

Molecular model of a bivalent-RGD peptide conjugated to an antisense oligonucleotide.

Integrin targeted lipoplexes

Cationic lipids have a long history as gene delivery carriers 47. Lipofectamine, DOTAP, Geneporter, DOTMA, to name a few, have already been commercialized and widely used 48-49. They form complexes with nucleic acids, also called lipoplexes, mainly through charge-charge interaction and hydrophobic forces 50. At physiological pH, the internal structure of the lipoplexes are laminar, onion-like, with nucleic acid layers sandwiched between lipid bilayers as determined by small angle x-ray scattering and transimission electric microscopy 51-53. The lipoplexes usually have a positive surface potential. Thus the unmodified lipoplexes enter the cells through endocytosis, as observed by electron microscopy 54. However, this process is nonspecific. To preferentially deliver the lipoplexes into cells specifically expressing αvβ3 integrin, targeted lipoplexes were prepared through incorporating RGD peptide. The formed targeted lipoplexes improved the delivery of functional genes or siRNA into various cell types including HUVEC, HeLa, 293T, NIH3T3, A549, U87, MDA-MB-231, human airway epithelial cells, human tracheal cells, and activated platelets 55-64.

Incorporation of polyethylene glycol (PEG) shielding is essential to introduce stealth-like properties 65-66. Lipoplexes modified this way become less susceptible to uptake by phagocytes and it also reduces the nonspecific interaction toward negatively charged sulfated proteoglycans on the cell surface, thus allowing long circulation time 67-68. Adding targeting moieties to stealth-like lipoplexes is expected to achieve high delivery specificity. PEG is widely used to provide shielding for delivery systems because of its biocompability, neutrality, hydrophilicity, flexibility, variable length and bulky hydrodynamic volume 69-70. Martin-Herranz et al. extensively explored the influence of PEG chain length on lipoplex properties 71. X-ray scattering found that incorporation of PEG with molecular weights 400 (PEG400) or 2000 (PEG2000) did not change the internal laminar phase of DOTAP-DNA complex. However, only PEG2000 provided sufficient shielding, which was evidenced by reduced inter-lipoplex interaction leading to blocked aggregation, and by interrupted cell-lipoplex interaction showing reduced transfection efficiency in fibroblasts. These authors further discovered that the shielding effect of PEG was less dependent on PEG density. For example, PEG400 even up to 20% ratio to cationic lipid didn't introduce effective shielding. However, PEG2000 completely shielded lipoplexes at a 6% ratio. Thus PEG with molecular weight above 2000 is widely used in developing long-circulating lipoplexes 63, 72. Besides providing a protective coat, it also acts as tether for targeting ligands to develop targeted lipoplex delivery systems 57-58, 64.

Recently, Wang et al. developed an integrin targeted lipoplex and tested its siRNA delivery efficiency in a mouse tumor model 64. This targeted lipoplex utilized a novel multifunctional lipid carrier abbreviated as EHCO to form complexes with anti-HIF-1a siRNA; the intent was to knock down HIF-1a, which is a key transcription factor responsible for tumor survival in hypoxic environments. RGD in the form of cyclo(RGDfK) was conjugated to PEG with molecular weight 3400 and directly linked onto the surface of this lipoplex through reaction between a maleimide group (-Mal) group on PEG and free thiol (-SH) groups on the EHCO. The molar ratio between targeting ligand and lipid carrier was 2.5%. For in vitro delivery in U87 cells, flow cytometry, confocal microscopy, and luciferase assays consistently demonstrated that PEG effectively reduced the nonspecific cell entry of the lipoplex, while RGD increased the receptor mediated delivery and the activity of the loaded siRNA. This RGD-directed lipoplex was then systemicaly delivered into athymic mice bearing human glioma U87 xenografts via intravenous injection using anti-HIF-1a siRNA dosed 2.5 mg/kg. At day 14, after five doses of siRNA, the tumor volume of the mice receiving targeted lipoplex was much smaller than the mice receiving nonmodified lipoplex with significance (P < 0.05). This result validated RGD-directed stealth-like lipoplexes as an effective systemic nucleic acid delivery system. It should be pointed out that delivery targeting integrins could achieve dual effects, with delivery of nucleic acids to both αvβ3 integrin-expressing angiogenic epithelial cells and αvβ3 positive tumor cells 64, 73.

Integrin targeted polymeric carriers

RGD-surface-modified nanoparticles, including polyplexes and liposomes, have been utilized to deliver therapeutic genes for a decade 74. However, adenovirus, with a diameter of 60-90 nm and using integrin as a secondary receptor for internalization 75, can be considered as the first integrin targeted nanoparticle. Seeking to emulate the superior transfection efficiency of adenovirus, polyethylenimine (PEI) was conjugated directly to the integrin-binding peptide CYGGRGDTP, which was then condensed with plasmid DNA to form particles 30-100 nm diameter 76. PEI-RGD/DNA complexes showed superior in vitro transfection efficiency compared to those with RGE in the peptide sequence 76, representing an initial success in mimicking adenovirus for gene delivery.

Further work sought to overcome the intrinsic problems of PEI polyplexes, such as non-specific binding to cell surfaces and serum proteins. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) was used as a spacer between RGD and PEI, and then the RGD-PEG-PEI polymers were condensed with plasmid DNA 77-78 or siRNA 79. The presence of PEG groups forms a hydrated barrier surrounding the nanoparticles that shields the defects in the cationic polyplexes and inhibits non-specific adsorption. Besides improvement of the in vitro activity, the latter study showed that RGD-PEG-PEI particles accumulated in tumor tissues overexpressing integrins and selectively delivered VEGFR2 siRNA to suppress tumor growth and angiogenesis 79. Recently, RGD-contained polymers have been further optimized. Polycation/DNA complexes were coated with multivalent N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) copolymers in one study 80. In another study, RGD-PEG-block-poly(lysine) was synthesized for gene delivery 81. Interestingly, condensing with this polymer did not enhance the cellular uptake of plasmid DNA, but improved expression of the plasmid dramatically in HeLa cells displaying αvβ3 integrin 81. Initial studies suggested that the presence of RGD peptide changed the intracellular trafficking route of the PEI polyplexes to a caveolar-mediated pathway followed by trafficking to the perinuclear region, thereby avoiding lysosomal degradation of delivered genes 81. Although the proposed mechanism was intriguing, the methods in this study, which heavily relied on microscopic observation, were descriptive and non-quantitative. Utilizing pharmacological and molecular inhibitors of endocytotic pathways can provide mechanistic information of intracellular trafficking of nanoparticles 4.

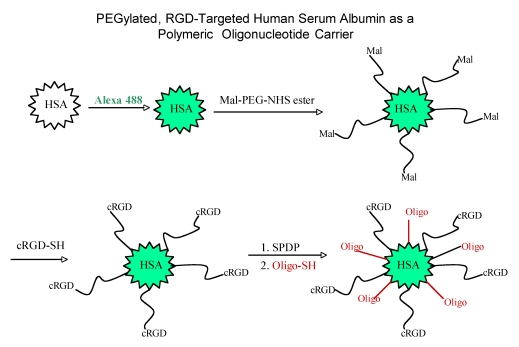

Other than PEI, RGD has also been conjugated to other polymeric carriers for delivery of nucleic acids, for example, carbon nanotubes 82, dendrimers 83, albumin 12, and gold nanoparticles 39. Inspired by the clustered RGD ligands displayed on five penton-base proteins in adenovirus, multiple RGD ligands were conjugated to gold nanoparticles to form so called RGD nanoclusters, and then were condensed with DNA/PEI complexes 39; the polyplex demonstrated superior in vitro activity. Another interesting RGD-based particle involved albumin conjugates (Fig 3), in which splice-shifting antisense oligonucleotides and PEG-RGD are linked to the same albumin molecules 12. The resultant complex (diameter of 6 nm) was smaller than most nanoparticles, and may obtain a better balance of avoiding being scavenged in the liver versus retention in tumor sites 12.

Figure 3.

Synthesis of an RGD targeted carrier for oligonucleotides using human serum albumin.

Compared to direct conjugates between nucleic acids and RGD ligands, polymeric carriers have a higher cargo capacity, which may lead to a better pharmacodynamics. The binding affinities of RGD peptides to integrin are typically at nanomolar levels, for example, 16 nM for the binding of a bivalent RGD peptide to the αvβ3 integrin 84. For delivery of the same amount of therapeutic nucleic acids, direct conjugates have more RGD ligands thus possibly saturating integrin receptors and resulting in inefficient receptor-mediated endocytosis. Another important factor affecting pharmacodynamics of nucleic acids is intracellular trafficking, from cellular uptake, vesicle trafficking, to release of the cargo at the target sites. Initial studies have indicated its importance 13, 81, however, more pharmacological and cell biological studies are needed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of nucleic acid trafficking.

Integrin targeted dendrimers

Dendrimers are spherical macromolecules with numerous inner branches, and are attractive molecules for the delivery of various types of nucleic acids (e.g., antisense oligonucleotide, siRNA, and plasmids) as well as traditional small organic molecules 85-91. As a delivery modality for nucleic acid, dendrimers have many advantages in terms of molecular structure, size and surface functional groups 92. Particularly, by selecting the generation of dendrimer, the size of dendrimer/nucleic acid complexes is adjustable to less than 200 nm, which is an important factor for tissue distribution through capillaries (~5 um) and passage through fenestrae between discontinuous endotherial cells (30-500 nm) of liver, spleen and bone marrow 93. Cellular delivery of nucleic acids by dendrimers has been limited in its effectiveness as well as in vivo efficacy. Excessive positive charge on dendrimer surfaces causes cytotoxicity due to non-specific interactions with negatively charged proteins on cell membranes 94-95 Also interactions with various serum proteins during blood circulation can disrupt delivery function, damaging nucleic acid before it gets to the target by the action of the endo/exo nucleases in blood 96.

The mechanism for dendrimer internalization in cells has been generally considered to be receptor mediated endocytosis which follows an endosome/lysosome pathway. However, recent studies indicate that cellular internalization of dendrimers is diverse and cell type dependent with different internalization pathways in different cells 97. Clathrin-coated pits, macropinocytosis, the caveolae-dependent pathway, and clathrin- and caveolin-independent pathways were reported for the cellular uptake and transport of dendrimer/nucleic acid complexes 97-100. For endosomal release of dendrimer and nucleic acid into cytoplasm, protonation in the acidic pH and Cl- ion influx in the late endosomal stage induces rapid swelling of the polymer matrix as well as conformational change, following by endosomal rupture thereby releasing nucleic acids into the cytoplasm 93. A recent study by Lee and Larson revealed a pore formation mechanism by the positively charged dendrimer 101. Dendrimers caused the formation of holes on the cell membrane leading to nonselective internalization into cell. The endocytotic pathway of RGD-dendrimer conjugates is little known and needs further investigation. Our previous studies with RGD carriers indicates that initial uptake of nucleic acid complexes by integrin receptors was followed via smooth vesicle trafficking, not clathin-coated pits, and at later points the complexes entered into endomembrane compartments 11-12.

The surface amino groups of dendrimers can be modified by attaching molecular ligands for selective targeting, for example, to recognize certain receptors expressed in disease sites 102-106. The αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins have been of particular interest since they are highly expressed on the luminal surface of endothelial cells during angiogenesis and also certain types of malignant cells 19, 107. High-affinity cyclic RGD peptide, (c(RGDfK)) selectively recognizing αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrin receptors was chosen to attain high affinity binding to this receptor 108. PAMAM dendrimer-RGD conjugates complexed with siRNA enhanced the siRNA delivery and reduced the progression of angiogenesis in the treatment of solid tumors 83, 109.

Pegylating the dendrimer surface shields positive charge of the dendrimer thus reducing nonspecific interactions with cell membranes and attenuates oxidative stress on the cell 110-111. Also pegylation increases the circulation time of the dendrimer in blood by avoiding the interaction of dendrimer surface amino groups with serum proteins 112-113. Prolonged circulation time in blood enhances the drug accumulation in diseased tissues (tumor or inflammatory site) via the EPR (enhanced permeability and retention) effect 114-115. Dendrimer-RGD-pegylation is a well-designed delivery adjunct that improves target selectivity as well as stability of the dendrimer complex with nucleic acids. Efficient intramuscular gene expression was mediated by PEG-conjugated PAMAM dendrimer 116-117.

The intracellular codelivery of nucleic acids and traditional chemotherapeutic drugs using dendrimers can be a promising approach for the development of multifunctional-drug carriers. With targeting ligands attached, the nanospace of the dendrimer interior can be used as a vehicle for encapsulation of chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., doxorubicin or paclitaxel) while the outer shell just beneath the dendrimer surface serves for nucleic acid shielding from the action of endo/exo nucleases 112. In recent study a generation-3 (G3) dendrimer was conjugated with PEG and RGD for codelivery of doxorubicin (DOX) and siRNA. Doxorubicin (DOX) was coupled to the RGD targeted nanoglobule via a degradable disulfide spacer to give G3-[PEG-RGD]-[DOX]; G3-[PEG-RGD]-[DOX] was further complexed with siRNA 109. The siRNA complexes of the targeted conjugate resulted in significantly higher gene silencing efficiency in U87-Luc cells than those of control conjugates G3-[PEG-RGD] and G3-[DOX]. Kang et. al. evaluated the efficiency of folate-polyamidoamine dendrimer conjugates (FA-PAMAM) for the in situ delivery of therapeutic antisense oligonucleotides (ASODN) to inhibit the growth of C6 glioma cells. ASODN from the FA-PAMAM knocked down EGFR expression in C6 glioma cells, both in vitro and in vivo 102. Quintana and colleagues synthesized an ethylenediamine core PAMAM dendrimer generation 5 which was covalently conjugated to folic acid, fluorescein, and methotrexate 118. This complex provides targeting, imaging and intracellular drug delivery capability with 100-fold decreased cytotoxicity over free methotrexate. Other multifunctional dendrimers have been prepared by covalently linking tumor targeting molecules such as folic acid (FA) or HER2-antibody, a sensing fluorescent molecule, and a chemotherapeutic drug such as methotrexate or taxol 103, 119-120. While these latter examples do not involve integrins, they establish approaches that could also be used in the integrin targeting area.

Conclusions

The integrin family of receptors provides interesting and useful targets for delivery of therapeutic oligonucleotides. Much has already been done using simple RGD peptides associated with a variety of carrier types (lipoplexes, dendrimers, other polymers). Additional peptide or small molecule ligands for non-RGD binding integrins are becoming available and should open the way to target additional members of this large receptor family. Finally, while many reports have appeared, we still know relatively little about the mechanisms involved in integrin-mediated delivery of nucleic acids; this will be an important theme for future investigation.

References

- 1.Manoharan M. Oligonucleotide conjugates as potential antisense drugs with improved uptake, biodistribution, targeted delivery, and mechanism of action. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 2002;12:103–28. doi: 10.1089/108729002760070849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Paula D, Bentley MV, Mahato RI. Hydrophobization and bioconjugation for enhanced siRNA delivery and targeting. RNA. 2007;13:431–56. doi: 10.1261/rna.459807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corey DR. Chemical modification: the key to clinical application of RNA interference? J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3615–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI33483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juliano R, Bauman J, Kang H, Ming X. Biological barriers to therapy with antisense and siRNA oligonucleotides. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:686–95. doi: 10.1021/mp900093r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dean NM, Bennett CF. Antisense oligonucleotide-based therapeutics for cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22:9087–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castanotto D, Rossi JJ. The promises and pitfalls of RNA-interference-based therapeutics. Nature. 2009;457:426–33. doi: 10.1038/nature07758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sazani P, Kole R. Therapeutic potential of antisense oligonucleotides as modulators of alternative splicing. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:481–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI19547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonauer A, Carmona G, Iwasaki M, Mione M, Koyanagi M, Fischer A. et al. MicroRNA-92a controls angiogenesis and functional recovery of ischemic tissues in mice. Science. 2009;324:1710–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1174381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crooke ST. Progress in antisense technology. Annu Rev Med. 2004;55:61–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.104408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitehead KA, Langer R, Anderson DG. Knocking down barriers: advances in siRNA delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:129–38. doi: 10.1038/nrd2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juliano R, Alam MR, Dixit V, Kang H. Mechanisms and strategies for effective delivery of antisense and siRNA oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:4158–71. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang H, Alam MR, Dixit V, Fisher M, Juliano RL. Cellular delivery and biological activity of antisense oligonucleotides conjugated to a targeted protein carrier. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:2182–8. doi: 10.1021/bc800270w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alam MR, Dixit V, Kang H, Li ZB, Chen X, Trejo J. et al. Intracellular delivery of an anionic antisense oligonucleotide via receptor-mediated endocytosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2764–76. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song E, Zhu P, Lee SK, Chowdhury D, Kussman S, Dykxhoorn DM. et al. Antibody mediated in vivo delivery of small interfering RNAs via cell-surface receptors. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:709–17. doi: 10.1038/nbt1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–87. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geiger B, Bershadsky A, Pankov R, Yamada KM. Transmembrane crosstalk between the extracellular matrix--cytoskeleton crosstalk. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:793–805. doi: 10.1038/35099066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz MA, Ginsberg MH. Networks and crosstalk: integrin signalling spreads. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:E65–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb0402-e65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juliano RL, Reddig P, Alahari S, Edin M, Howe A, Aplin A. Integrin regulation of cell signalling and motility. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:443–6. doi: 10.1042/BST0320443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juliano RL. Signal transduction by cell adhesion receptors and the cytoskeleton: functions of integrins, cadherins, selectins, and immunoglobulin-superfamily members. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:283–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.090401.151133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edin ML, Juliano RL. Raf-1 serine 338 phosphorylation plays a key role in adhesion-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase by epidermal growth factor. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4466–75. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4466-4475.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alahari SK, Reddig PJ, Juliano RL. The integrin-binding protein Nischarin regulates cell migration by inhibiting PAK. EMBO J. 2004;23:2777–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aplin AE, Stewart SA, Assoian RK, Juliano RL. Integrin-mediated adhesion regulates ERK nuclear translocation and phosphorylation of Elk-1. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:273–82. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.2.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moschos SJ, Drogowski LM, Reppert SL, Kirkwood JM. Integrins and cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2007;21:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo W, Giancotti FG. Integrin signalling during tumour progression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:816–26. doi: 10.1038/nrm1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felding-Habermann B, Mueller BM, Romerdahl CA, Cheresh DA. Involvement of integrin alpha V gene expression in human melanoma tumorigenicity. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:2018–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI115811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stupack DG, Cheresh DA. Integrins and angiogenesis. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2004;64:207–38. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(04)64009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sczekan MM, Juliano RL. Internalization of the fibronectin receptor is a constitutive process. J Cell Physiol. 1990;142:574–80. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041420317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bretscher MS. Circulating integrins: α5β1, α6β4 and Mac-1, but not α3β1, α4β1 or LFA-1. EMBO J. 1992;11:405–10. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caswell PT, Norman JC. Integrin trafficking and the control of cell migration. Traffic. 2006;7:14–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White DP, Caswell PT, Norman JC. αvβ3 and α5β1 integrin recycling pathways dictate downstream Rho kinase signaling to regulate persistent cell migration. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:515–25. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caswell PT, Chan M, Lindsay AJ, McCaffrey MW, Boettiger D, Norman JC. Rab-coupling protein coordinates recycling of α5β1 integrin and EGFR1 to promote cell migration in 3D microenvironments. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:143–55. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woods AJ, White DP, Caswell PT, Norman JC. PKD1/PKCmu promotes αvβ3 integrin recycling and delivery to nascent focal adhesions. EMBO J. 2004;23:2531–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wary KK, Mariotti A, Zurzolo C, Giancotti FG. A requirement for caveolin-1 and associated kinase Fyn in integrin signaling and anchorage-dependent cell growth. Cell. 1998;94:625–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Powelka AM, Sun J, Li J, Gao M, Shaw LM, Sonnenberg A. et al. Stimulation-dependent recycling of integrin beta1 regulated by ARF6 and Rab11. Traffic. 2004;5:20–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Upla P, Marjomaki V, Kankaanpaa P, Ivaska J, Hyypia T, Van Der Goot FG. et al. Clustering induces a lateral redistribution of α2β1 integrin from membrane rafts to caveolae and subsequent protein kinase C-dependent internalization. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:625–36. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Veldhoen S, Laufer SD, Restle T. Recent developments in Peptide-based nucleic Acid delivery. Int J Mol Sci. 2008;9:1276–320. doi: 10.3390/ijms9071276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lebleu B, Moulton HM, Abes R, Ivanova GD, Abes S, Stein DA. et al. Cell penetrating peptide conjugates of steric block oligonucleotides. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:517–29. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gogoi K, Mane MV, Kunte SS, Kumar VA. A versatile method for the preparation of conjugates of peptides with DNA/PNA/analog by employing chemo-selective click reaction in water. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e139. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chao J, Huang WY, Wang J, Xiao SJ, Tang YC, Liu JN. Click-chemistry-conjugated oligo-angiomax in the two-dimensional DNA lattice and its interaction with thrombin. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:877–83. doi: 10.1021/bm8014076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edupuganti OP, Renaudet O, Defrancq E, Dumy P. The oxime bond formation as an efficient chemical tool for the preparation of 3',5'-bifunctionalised oligodeoxyribonucleotides. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:2839–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edupuganti OP, Singh Y, Defrancq E, Dumy P. New strategy for the synthesis of 3',5'-bifunctionalized oligonucleotide conjugates through sequential formation of chemoselective oxime bonds. Chemistry. 2004;10:5988–95. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villien M, Defrancq E, Dumy P. Chemoselective oxime and thiazolidine bond formation: a versatile and efficient route to the preparation of 3'-peptide-oligonucleotide conjugates. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2004;23:1657–66. doi: 10.1081/NCN-200031467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh Y, Spinelli N, Defrancq E, Dumy P. A novel heterobifunctional linker for facile access to bioconjugates. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:1413–9. doi: 10.1039/b518151h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spinelli N, Edupuganti OP, Defrancq E, Dumy P. New solid support for the synthesis of 3'-oligonucleotide conjugates through glyoxylic oxime bond formation. Org Lett. 2007;9:219–22. doi: 10.1021/ol062607b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Forget D, Boturyn D, Defrancq E, Lhomme J, Dumy P. Highly efficient synthesis of peptide-oligonucleotide conjugates: chemoselective oxime and thiazolidine formation. Chemistry. 2001;7:3976–84. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010917)7:18<3976::aid-chem3976>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alam MR, Ming X, Dixit V, Fisher M, Chen X, Juliano RL. The biological effect of an antisense oligonucleotide depends on its route of endocytosis and trafficking. Oligonucleotides. 2010;20:103–9. doi: 10.1089/oli.2009.0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Felgner PL, Gadek TR, Holm M, Roman R, Chan HW, Wenz M. et al. Lipofection: a highly efficient, lipid-mediated DNA-transfection procedure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:7413–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Behr JP, Demeneix B, Loeffler JP, Perez-Mutul J. Efficient gene transfer into mammalian primary endocrine cells with lipopolyamine-coated DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:6982–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.6982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meyer KB, Thompson MM, Levy MY, Barron LG, Szoka FCJr. Intratracheal gene delivery to the mouse airway: characterization of plasmid DNA expression and pharmacokinetics. Gene Ther. 1995;2:450–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matulis D, Rouzina I, Bloomfield VA. Thermodynamics of cationic lipid binding to DNA and DNA condensation: roles of electrostatics and hydrophobicity. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7331–42. doi: 10.1021/ja0124055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bell PC, Bergsma M, Dolbnya IP, Bras W, Stuart MC, Rowan AE. et al. Transfection mediated by gemini surfactants: engineered escape from the endosomal compartment. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1551–8. doi: 10.1021/ja020707g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koltover I, Salditt T, Radler JO, Safinya CR. An inverted hexagonal phase of cationic liposome-DNA complexes related to DNA release and delivery. Science. 1998;281:78–81. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koltover I, Wagner K, Safinya CR. DNA condensation in two dimensions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14046–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zabner J, Fasbender AJ, Moninger T, Poellinger KA, Welsh MJ. Cellular and molecular barriers to gene transfer by a cationic lipid. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18997–9007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anwer K, Kao G, Rolland A, Driessen WH, Sullivan SM. Peptide-mediated gene transfer of cationic lipid/plasmid DNA complexes to endothelial cells. J Drug Target. 2004;12:215–21. doi: 10.1080/10611860410001724468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Colin M, Harbottle RP, Knight A, Kornprobst M, Cooper RG, Miller AD. et al. Liposomes enhance delivery and expression of an RGD-oligolysine gene transfer vector in human tracheal cells. Gene Ther. 1998;5:1488–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gupta AS, Huang G, Lestini BJ, Sagnella S, Kottke-Marchant K, Marchant RE. RGD-modified liposomes targeted to activated platelets as a potential vascular drug delivery system. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:106–14. doi: 10.1160/TH04-06-0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harvie P, Dutzar B, Galbraith T, Cudmore S, O'Mahony D, Anklesaria P. et al. Targeting of lipid-protamine-DNA (LPD) lipopolyplexes using RGD motifs. J Liposome Res. 2003;13:231–47. doi: 10.1081/lpr-120026389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leblond J, Mignet N, Leseurre L, Largeau C, Bessodes M, Scherman D. et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of enhanced DNA binding new lipopolythioureas. Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17:1200–8. doi: 10.1021/bc060110g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Renigunta A, Krasteva G, Konig P, Rose F, Klepetko W, Grimminger F. et al. DNA transfer into human lung cells is improved with Tat-RGD peptide by caveoli-mediated endocytosis. Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17:327–34. doi: 10.1021/bc050263o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scott ES, Wiseman JW, Evans MJ, Colledge WH. Enhanced gene delivery to human airway epithelial cells using an integrin-targeting lipoplex. J Gene Med. 2001;3:125–34. doi: 10.1002/jgm.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zuber G, Dontenwill M, Behr JP. Synthetic viruslike particles for targeted gene delivery to αvβ3 integrin-presenting endothelial cells. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:1544–52. doi: 10.1021/mp900105q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang XL, Xu R, Lu ZR. A peptide-targeted delivery system with pH-sensitive amphiphilic cell membrane disruption for efficient receptor-mediated siRNA delivery. J Control Release. 2009;134:207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang XL, Xu R, Wu X, Gillespie D, Jensen R, Lu ZR. Targeted systemic delivery of a therapeutic siRNA with a multifunctional carrier controls tumor proliferation in mice. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:738–46. doi: 10.1021/mp800192d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Allen TM. Long-circulating (sterically stabilized) liposomes for targeted drug delivery. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15:215–20. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Woodle MC. Sterically stabilized liposome therapeutics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1995;16:249–65. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lasic DD, Papahadjopoulos D. Liposomes revisited. Science. 1995;267:1275–6. doi: 10.1126/science.7871422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mislick KA, Baldeschwieler JD. Evidence for the role of proteoglycans in cation-mediated gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:12349–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zalipsky S. Functionalized poly(ethylene glycol) for preparation of biologically relevant conjugates. Bioconjug Chem. 1995;6:150–65. doi: 10.1021/bc00032a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ryan SM, Mantovani G, Wang X, Haddleton DM, Brayden DJ. Advances in PEGylation of important biotech molecules: delivery aspects. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2008;5:371–83. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martin-Herranz A, Ahmad A, Evans HM, Ewert K, Schulze U, Safinya CR. Surface functionalized cationic lipid-DNA complexes for gene delivery: PEGylated lamellar complexes exhibit distinct DNA-DNA interaction regimes. Biophys J. 2004;86:1160–8. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74190-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Akinc A, Goldberg M, Qin J, Dorkin JR, Gamba-Vitalo C, Maier M. et al. Development of lipidoid-siRNA formulations for systemic delivery to the liver. Mol Ther. 2009;17:872–9. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grzelinski M, Urban-Klein B, Martens T, Lamszus K, Bakowsky U, Hobel S. et al. RNA interference-mediated gene silencing of pleiotrophin through polyethylenimine-complexed small interfering RNAs in vivo exerts antitumoral effects in glioblastoma xenografts. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:751–66. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dunehoo AL, Anderson M, Majumdar S, Kobayashi N, Berkland C, Siahaan TJ. Cell adhesion molecules for targeted drug delivery. J Pharm Sci. 2006;95:1856–72. doi: 10.1002/jps.20676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stewart PL, Chiu CY, Huang S, Muir T, Zhao Y, Chait B. et al. Cryo-EM visualization of an exposed RGD epitope on adenovirus that escapes antibody neutralization. EMBO J. 1997;16:1189–98. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Erbacher P, Remy JS, Behr JP. Gene transfer with synthetic virus-like particles via the integrin-mediated endocytosis pathway. Gene Ther. 1999;6:138–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kunath K, Merdan T, Hegener O, Haberlein H, Kissel T. Integrin targeting using RGD-PEI conjugates for in vitro gene transfer. J Gene Med. 2003;5:588–99. doi: 10.1002/jgm.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Woodle MC, Scaria P, Ganesh S, Subramanian K, Titmas R, Cheng C. et al. Sterically stabilized polyplex: ligand-mediated activity. J Control Release. 2001;74:309–11. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00339-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schiffelers RM, Ansari A, Xu J, Zhou Q, Tang Q, Storm G. et al. Cancer siRNA therapy by tumor selective delivery with ligand-targeted sterically stabilized nanoparticle. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e149. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhou QH, You YZ, Wu C, Huang Y, Oupicky D. Cyclic RGD-targeting of reversibly stabilized DNA nanoparticles enhances cell uptake and transfection in vitro. J Drug Target. 2009;17:364–73. doi: 10.1080/10611860902807046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oba M, Aoyagi K, Miyata K, Matsumoto Y, Itaka K, Nishiyama N. et al. Polyplex micelles with cyclic RGD peptide ligands and disulfide cross-links directing to the enhanced transfection via controlled intracellular trafficking. Mol Pharm. 2008;5:1080–92. doi: 10.1021/mp800070s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Villa CH, McDevitt MR, Escorcia FE, Rey DA, Bergkvist M, Batt CA. et al. Synthesis and biodistribution of oligonucleotide-functionalized, tumor-targetable carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2008;8:4221–8. doi: 10.1021/nl801878d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Waite CL, Roth CM. PAMAM-RGD Conjugates enhance siRNA delivery through a multicellular spheroid model of malignant glioma. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:1908–16. doi: 10.1021/bc900228m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen X, Plasencia C, Hou Y, Neamati N. Synthesis and biological evaluation of dimeric RGD peptide-paclitaxel conjugate as a model for integrin-targeted drug delivery. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1098–106. doi: 10.1021/jm049165z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu XX, Rocchi P, Qu FQ, Zheng SQ, Liang ZC, Gleave M. et al. PAMAM dendrimers mediate siRNA delivery to target Hsp27 and produce potent antiproliferative effects on prostate cancer cells. ChemMedChem. 2009;4:1302–10. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Patil ML, Zhang M, Betigeri S, Taratula O, He H, Minko T. Surface-modified and internally cationic polyamidoamine dendrimers for efficient siRNA delivery. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1396–403. doi: 10.1021/bc8000722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Juliano RL. Intracellular delivery of oligonucleotide conjugates and dendrimer complexes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1082:18–26. doi: 10.1196/annals.1348.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Omidi Y, Hollins AJ, Drayton RM, Akhtar S. Polypropylenimine dendrimer-induced gene expression changes: the effect of complexation with DNA, dendrimer generation and cell type. J Drug Target. 2005;13:431–43. doi: 10.1080/10611860500418881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yoo H, Juliano RL. Enhanced delivery of antisense oligonucleotides with fluorophore-conjugated PAMAM dendrimers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4225–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.21.4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bielinska A, Kukowska-Latallo JF, Johnson J, Tomalia DA, Baker JRJr. Regulation of in vitro gene expression using antisense oligonucleotides or antisense expression plasmids transfected using starburst PAMAM dendrimers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2176–82. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.11.2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jain NK, Asthana A. Dendritic systems in drug delivery applications. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2007;4:495–512. doi: 10.1517/17425247.4.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee CC, MacKay JA, Frechet JM, Szoka FC. Designing dendrimers for biological applications. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1517–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dutta T, Jain NK, McMillan NA, Parekh HS. Dendrimer nanocarriers as versatile vectors in gene delivery. Nanomedicine. 2010;6:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jevprasesphant R, Penny J, Jalal R, Attwood D, McKeown NB, D'Emanuele A. The influence of surface modification on the cytotoxicity of PAMAM dendrimers. Int J Pharm. 2003;252:263–6. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00623-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fischer D, Li Y, Ahlemeyer B, Krieglstein J, Kissel T. In vitro cytotoxicity testing of polycations: influence of polymer structure on cell viability and hemolysis. Biomaterials. 2003;24:1121–31. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00445-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mukherjee SP, Davoren M, Byrne HJ. In vitro mammalian cytotoxicological study of PAMAM dendrimers - Towards quantitative structure activity relationships. Toxicol In Vitro. 2010;24:169–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Manunta M, Nichols BJ, Tan PH, Sagoo P, Harper J, George AJ. Gene delivery by dendrimers operates via different pathways in different cells, but is enhanced by the presence of caveolin. J Immunol Methods. 2006;314:134–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Grosse S, Aron Y, Thevenot G, Francois D, Monsigny M, Fajac I. Potocytosis and cellular exit of complexes as cellular pathways for gene delivery by polycations. J Gene Med. 2005;7:1275–86. doi: 10.1002/jgm.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Saovapakhiran A, D'Emanuele A, Attwood D, Penny J. Surface modification of PAMAM dendrimers modulates the mechanism of cellular internalization. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:693–701. doi: 10.1021/bc8002343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Manunta M, Tan PH, Sagoo P, Kashefi K, George AJ. Gene delivery by dendrimers operates via a cholesterol dependent pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2730–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hong S, Rattan R, Majoros IJ, Mullen DG, Peters JL, Shi X. et al. The role of ganglioside GM(1) in cellular internalization mechanisms of poly(amidoamine) dendrimers. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:1503–13. doi: 10.1021/bc900029k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kang C, Yuan X, Li F, Pu P, Yu S, Shen C. et al. Evaluation of folate-PAMAM for the delivery of antisense oligonucleotides to rat C6 glioma cells in vitro and in vivo. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;93:585–94. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shukla R, Thomas TP, Peters JL, Desai AM, Kukowska-Latallo J, Patri AK. et al. HER2 specific tumor targeting with dendrimer conjugated anti-HER2 mAb. Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17:1109–15. doi: 10.1021/bc050348p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Boswell CA, Eck PK, Regino CA, Bernardo M, Wong KJ, Milenic DE. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation of integrin αvβ3-targeted PAMAM dendrimers. Mol Pharm. 2008;5:527–39. doi: 10.1021/mp800022a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hill E, Shukla R, Park SS, Baker JRJr. Synthetic PAMAM-RGD conjugates target and bind to odontoblast-like MDPC 23 cells and the predentin in tooth organ cultures. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:1756–62. doi: 10.1021/bc0700234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yang H, Kao WJ. Synthesis and characterization of nanoscale dendritic RGD clusters for potential applications in tissue engineering and drug delivery. Int J Nanomedicine. 2007;2:89–99. doi: 10.2147/nano.2007.2.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Silva R, D'Amico G, Hodivala-Dilke KM, Reynolds LE. Integrins: the keys to unlocking angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1703–13. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.172015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wermelinger LS, Geraldo RB, Frattani FS, Rodrigues CR, Juliano MA, Castro HC. et al. Integrin inhibitors from snake venom: exploring the relationship between the structure and activity of RGD-peptides. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;482:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kaneshiro TL, Lu ZR. Targeted intracellular codelivery of chemotherapeutics and nucleic acid with a well-defined dendrimer-based nanoglobular carrier. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5660–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lee H, Larson RG. Molecular dynamics study of the structure and interparticle interactions of polyethylene glycol-conjugated PAMAM dendrimers. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:13202–7. doi: 10.1021/jp906497e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang W, Xiong W, Wan J, Sun X, Xu H, Yang X. The decrease of PAMAM dendrimer-induced cytotoxicity by PEGylation via attenuation of oxidative stress. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:105103. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/10/105103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Guillaudeu SJ, Fox ME, Haidar YM, Dy EE, Szoka FC, Frechet JM. PEGylated dendrimers with core functionality for biological applications. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:461–9. doi: 10.1021/bc700264g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Froehlich E, Mandeville JS, Jennings CJ, Sedaghat-Herati R, Tajmir-Riahi HA. Dendrimers bind human serum albumin. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:6986–93. doi: 10.1021/jp9011119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kaminskas LM, Wu Z, Barlow N, Krippner GY, Boyd BJ, Porter CJ. Partly-PEGylated Poly-L-lysine dendrimers have reduced plasma stability and circulation times compared with fully PEGylated dendrimers. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98:3871–5. doi: 10.1002/jps.21692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Okuda T, Kawakami S, Akimoto N, Niidome T, Yamashita F, Hashida M. PEGylated lysine dendrimers for tumor-selective targeting after intravenous injection in tumor-bearing mice. J Control Release. 2006;116:330–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Qi R, Gao Y, Tang Y, He RR, Liu TL, He Y. et al. PEG-conjugated PAMAM dendrimers mediate efficient intramuscular gene expression. AAPS J. 2009;11:395–405. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9116-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Taratula O, Garbuzenko OB, Kirkpatrick P, Pandya I, Savla R, Pozharov VP. et al. Surface-engineered targeted PPI dendrimer for efficient intracellular and intratumoral siRNA delivery. J Control Release. 2009;140:284–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Quintana A, Raczka E, Piehler L, Lee I, Myc A, Majoros I. et al. Design and function of a dendrimer-based therapeutic nanodevice targeted to tumor cells through the folate receptor. Pharm Res. 2002;19:1310–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1020398624602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Singh P, Gupta U, Asthana A, Jain NK. Folate and folate-PEG-PAMAM dendrimers: synthesis, characterization, and targeted anticancer drug delivery potential in tumor bearing mice. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:2239–52. doi: 10.1021/bc800125u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Thomas TP, Myaing MT, Ye JY, Candido K, Kotlyar A, Beals J. et al. Detection and analysis of tumor fluorescence using a two-photon optical fiber probe. Biophys J. 2004;86:3959–65. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.034462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]