Abstract

Introduction

Nitroimidazole (azomycin) derivatives labeled with radioisotopes have been developed as cancer imaging and radiotherapeutic agents based on the oncological hypoxic mechanism. By attaching nitroimidazole core with different functional groups, we synthesized new nitroimidazole derivatives, and evaluated their potentiality as tumor imaging agents.

Methods

Starting with commercially available 2-nitroimdazole, 2-fluoro-N-(2-(2-nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)acetamide (NEFA, [19F]7) and 2-(2-methyl-5-nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl 2-fluoroacetate (NEFT, [19F]8), as well as radiolabeling precursors - the bromo substituted analogs were quickly synthesized through a three-step synthetic pathway. The precursors were radiolabeled with [18F]F-/18-crown-6/KHCO3 in DMSO at 90 °C for 10 min followed by purification with an Oasis HLB cartridge. Biodistribution studies were carried out in EMT-6 tumor-bearing mice. The uptake (%ID/g) in tumors and normal tissues were measured at 30 min post injection. Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (LC/MS) was used to distinguish metabolites from parent drugs in urine and plasma of rat injected with “cold” NEFA ([19F]7) and NEFT ([19F]8).

Results

Two radiotracers, [18F]NEFA ([18F]7) and [18F]NEFT ([18F]8), were prepared with average yields of 6-7% and 9-10% (no decay corrected). Radiochemical purity for both tracers was >95% as determined by HPLC. Biodistribution studies in EMT-6 tumor-bearing mice indicated that the tumor to blood and tumor to liver ratios of both [18F]7 (0.96, 0.98) and [18F]8 (0.61,1.10) at 30 min were higher than those observed for [18F]FMISO (1) (0.91, 0.59), a well-investigated azomycin type hypoxia radiotacer. LC/MS analysis demonstrated that fluoroacetate was the main in vivo metabolite for both NEFA ([19F]7) and NEFT ([19F]8).

Conclusions

In this research, two new fluorine-18 labeled 2-nitroimdazole derivatives, [18F]7 and [18F]8, both of which containing in vivo hydrolyzable group, were successfully prepared. Further biological evaluations are warranted to investigate their potential as PET radioligands for imaging tumor.

Keywords: PET, 2-nitroimidazole, 18F, hypoxia

1 Introduction

Hypoxia has been recognized as a characteristic of almost all types of solid tumors. In case of cancer, the presence of hypoxic cells may play a role in their resistance to both radiation and anticancer treatment [1-4]. It is a characteristic feature of locally advanced solid tumors, has become known as a pivotal factor of the tumor pathology since it can promote tumor progression and resistance to therapy [4]. Thus, noninvasive imaging methods for identification and quantitation of tumor hypoxia with positron emmision tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) have received serious attention to predict and monitor treatment response [5-8].

It was postulated that radiolabeled 2-nitroimidazole-based radiosensitizers could be used for scintigraphic imaging of tumor hypoxia by Chapman in 1981 [9]. The nitro group undergoes an enzyme-mediated electron transfer to a free radical anion, which is reversible in the presence of oxygen. Unlike in normal cells, further reductions of this free anion produce more chemically reactive species that lead to adduct formation with cellular components by metabolically viable reductases. These adduct formations can prevent egress of 2-nitroimidazoles and cause selective trapping of the azomycin in hypoxic cells [10].

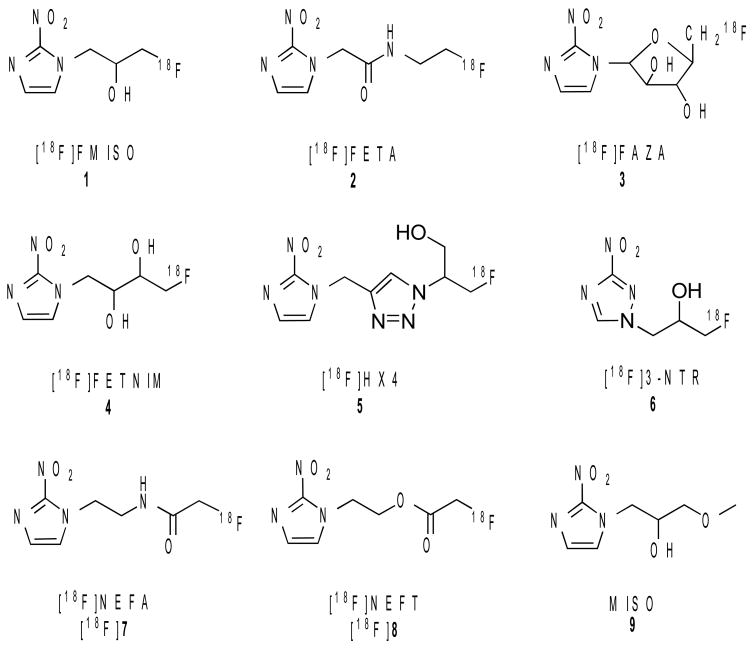

[18F]Fluoromisonidazole ([18F]FMISO (1)) was derived from misonidazole (9), one of the earliest radiosensitizers used in radiation therapy. It is the most widely used PET agent for mapping original hypoxia with hundreds of patient studies reported [8, 11-14]. [18F]FMISO (1) is easily synthesized, and can be safely used in humans. However, [18F]FMISO (1) was not an optimal hypoxic imaging agent. Because of the partitioning mechanism, [18F]FMISO (1) shows a reduced accumulation of radioactivity in hypoxic cells and slow clearance in normal cells that lead to low tumor-to-background (T/B) ratios [8, 15]. Thus, new imaging agents with faster pharmacokinetics for ensuring higher T/B ratios are required. Several alternative nitroimidazole derivatives labeled with 18F, such as [18F]FETA (2), [18F]FAZA (3), [18F]FETNIM (4), [18F]HX4 (5) and [18F]3-NTR (6) (Fig. 1) have been reported [16-23]. In this report, we aim to develop 2-nitroimidazole derivatives with enzymatically or chemically labile groups, either an ester or an amide linkage. In the presence of carboxylesterases, peptidases or proteases, such derivatives are expected to be hydrolyzed in vivo to [18F]fluoroacetate, a metabolite which owns a rapid clearance in normal tissues, and to get a high T/B ratio [24]. A novel approach of using the in vivo hydrolysis of ethyl ester of [18F]fluoroacetate for penetrating intact blood-brain barrier and evaluating glia cell metabolism has recently been reported [25]. We report, herein the synthesis of [18F]NEFA ([18F]7) and [18F]NEFT ([18F]8) (Fig. 1) and results of preliminary biological evaluation of these two radiotracers in EMT-6 tumor-bearing murine model.

Fig. 1.

Structures of known 2-nitroimidazole derivatives as hypoxia imaging agents: [18F]FMISO, 1, [18F]FETA, 2, [18F]FAZA, 3, [18F]FETNIM, 4, [18F]HX4, 5 [18F]3-NTR, 6, two new target molecules: [18F]NEFA, [18F]7 and [18F]NEFT, [18F]8 and misonidazole, 9.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 General

All chemicals were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co. and used without further purification unless otherwise indicated. Solvents were dried through a molecular sieve system (Pure Solve Solvent Purification System; Innovative Technology, Inc.). 1HNMR spectra were obtained at 200MHz in CDCl3 (Bruker DPX 200 Spectrometer). Chemical shifts are reported as δ values (parts per million) relative to residual protons of deuterated solvent. Coupling constants are reported in Hertz (Hz). The multiplicity is defined by s (singlet), d (doublet), t (tripled), br (broad), or m (multiplet). Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was run on pre-coated plates of silica gel 60 F254. Flash chromatography was performed using silica gel 60 (230 - 400 mesh, Sigma-Aldrich). Radioisotope 18F enriched aqueous solution was purchased from IBA (IBA Molecular North America, Inc.). Solid-phase extraction cartridges were obtained from Waters (Oasis HLB 3cc, QMA light) (Fisher Scientific).

Synthesis

tert-Butyl 2-(2-nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethylcarbamate (11)

A mixture of 10 (2 mmol, 226 mg), tert-butyl 2-bromoethylcarbamate (3 mmol, 669 mg), sodium iodide (NaI) (0.2 mmol, 29 mg) and sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) (4 mmol, 552 mg) was stirring in 5 mL N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) at 60 °C for 48 h. The mixture was then diluted with 15 mL ethyl acetate (EtOAc), and washed by water (H2O) (10 mL × 2) as well as brine (5 mL × 1). The organic layer was dried by anhydrous sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) and filtered. The filtration was concentrated, and the residual was purified by flash chromatography (EtOAc/hexane: 1/1) to give 447 mg white solid 11 (yield: 87%): 1HNMR δ: 7.12(d, 1H), 7.03(d, 1H), 4.70(s, 1H), 4.51-4.57(t, 3H), 3.48-3.57(m, 2H), 1.39(s, 9H).

2-(2-Nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethanamine (12)

A solution of 11 (1.05 mmol, 270 mg) in 5 mL trifluoracetic acid (TFA)/dichloromethane (DCM) (1:1) was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. Removal of solvent gave a yellow oil. After several times of co-evaporation with methanol, 273 mg 12 (yield: 96%) was given as a white solid: 1HNMR δ: 7.57(s, 1H), 7.29(s, 1H), 4.84-4.90(m, 2H), 3.56-3.62(t, 2H).

2-Fluoro-N-(2-(2-nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)acetamide ([19F]7)

Fluoroacetyl chloride (5.48 mmol, 529 mg) was added to 12 (1.37 mmol, 370 mg) in 5 mL DCM and 0.74 mL triethylamine (Et3N) at 0 °C in 5 min. After stirring overnight, the solution was diluted with 10 mL DCM, and washed with H2O (10 mL × 2) as well as brine (5 mL × 1). The organic layer was dried by anhydrous Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtration was concentrated and the residual was purified by flash chromatography (EtOAc/hexanes: 8 /2) to give 166 mg white solid [19F]7 (yield: 56%): 1HNMR δ: 7.17(s, 1H), 7.08(s, 1H), 6.61(s, 1H), 4.93(s, 1H), 4.69(s, 1H), 4.61-4.67(t, 2H), 3.80-3.83(m, 2H). 13CNMR δ: 167.08, 131.07, 128.68, 127.20, 49.06, 40.42, 28.58. HRMS (ESI) calculated for C7H10FN4O3(MH+), 217.0737; found, 217.0737 (M++H).

2-Bromo-N-(2-(2-nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)acetamide(13)

Bromoacetyl bromide (3 mmol, 605 mg) was added to 12 (1.01 mmol, 270 mg) in 5 ml DCM and 0.5 ml Et3N at 0 °C in 5 min. After stirring overnight, the mixture was diluted with 10 ml DCM, and washed with H2O (10 mL × 2) as well as brine (5 mL × 1). The organic layer was dried by anhydrous Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtration was concentrated and the residual crude product was purified by flash chromatography (EtOAc/hexane: 8/2) to give 160 mg white solid 13 (yield: 58%): 1HNMR δ: 7.14(d, 1H), 7.08(d, 1H), 6.88(s, 1H), 4.60-4.66(t, 2H), 3.87(s, 1H), 3.73-3.82(m, 2H). 13CNMR δ: 168.60, 144.94, 127.57, 127.15, 48.82, 39.13, 26.88. HRMS (ESI) calculated for C7H10BrN4O3(MH+), 276.9936; found 276.9936.

1-(2-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyloxy)ethyl)-2-nitro-1H-imidazole (14)

A mixture of 10 (2.65 mmol, 300 mg), (2-bromoethoxy)(tert-butyl)dimethylsilane (3.77 mmol, 900 mg) and potasium carbonate (K2CO3) (2.90 mmol, 400 mg) was stirring in 10 mL DMF at 100 °C for 4 h. The mixture was then diluted with 15 mL EtOAc, and washed by H2O (10 mL × 2) as well as brine (5 mL × 1). The organic layer was dried by anhydrous Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtration was concentrated, and the residual crude product was purified by flash chromatography (EtOAc/hexane: 3/7) to give 696 mg white solid 14 (yield: 97%): 1HNMR δ: 7.15(s, 1H), 7.14(s, 1H), 4.53-4.58(t,2H), 3.93-3.98(t, 2H), 0.84(s, 9H), 0.05(s, 3H).

2-(2-Nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethanol (15)

To a solution of 12 (2.6 mmol, 696 mg) in 5 mL tetrahydrofuran (THF) was added 5 mL HCl solution (0.5 mL 1% HCl in 4.5 mL ethanol) dropwise at room temperature. After 3 h, the mixture was cooled to 0 °C, and neutralized with 10% Na2CO3. The aqueous layer was extracted with chloroform (20 mL × 3). The organic layer was dried by anhydrous Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtration was concentrated, and the residual crude product was purified by flash chromatography (EtOAc/hexane: 1/1) to give 122 mg white solid 15 (yield: 87%): 1HNMR δ: 7.21(s, 1H), 7.06(s, 1H), 4.47-4.52(t, 2H), 3.84-3.90(t, 2H), 3.14(s, 1H).

2-(2-Nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl 2-fluoroacetate ([19F]8)

Compound [19F]8 was prepared from 15 (0.50 mmol, 78.5 mg), fluoroacetyl chloride (1 mmol, 96.5 mg) and Et3N (0.5 mL) in 5 mL DCM, with the same procedure described for compound [19F]7. Compound [19F]8: 30 mg (yield: 37%): 1HNMR δ: 7.19(d, 1H), 7.12(s, 1H), 4.96(s, 1H), 4.74-4.77(dt, 2H), 4.72(s, 1H), 4.60-4.65(dt, 2H). 13CNMR δ: 167.61, 167.18, 128.82, 126.59, 75.62, 63.35, 48.73. HRMS (ESI) calculated for C7H9BrN3O4(MH+), 218.0577; found, 218.0577.

2-(2-Nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl 2-bromoacetate(16)

Compound 16 was prepared from 13 (0.51 mmol, 79 mg), bromoacetyl bromide (1 mmol, 202 mg) and Et3N (0.5 mL) in 5 mL DCM, with the same procedure described for compound 13. Compound 16: 124 mg (yield: 90%). 1HNMR δ: 7.11(d, 1H), 7.08(d, 1H), 4.63-4.70(m, 2H), 4.48-4.54(m, 2H), 3.73(s, 2H). 13CNMR δ: 166.86, 128.83, 126.76, 64.14, 48.78, 24.94. HRMS (ESI) calculated for C7H9BrN3O4(MH+), 276.9776; found, 277.9772.

2.2 Radiolabeling

An aqueous solution of [18F]F-, produced by cyclotron using 18O (p, n) 18F reaction, was passed through a Sep-Pak Light QMA cartridge. The cartridge was dried with argon, and the 18F activity was eluted with a 1.0 mL of 18-crown-6/KHCO3 solution (7 mg 18-crown-6 and 2 mg KHCO3 in 1 mL CH3CN/H2O 8/2). The solvent was then evaporated at 110 °C under an argon stream. Furthermore, the residue was azeotropically dried twice with 1.0 mL anhydrous CH3CN at 110 °C under an argon stream. A solution of bromide precursor 13 (2 mg) or 16 (2 mg) in 1 mL DMSO was added to the dried [18F] KF/18-crown-6 complex, and heated at 90 °C for 10 min. The mixture was cooled down for 1 min, then diluted with 6 mL water and passed through an Oasis HLB3-mL cartridge (pretreated with 10 mL EtOH, followed with 10 mL water). [18F]7 or [18F]8, trapped in the HLB cartridge, was rinsed with 4 mL H2O and eluted with 1 mL EtOH. When animal experiments were performed, the final product was dilute with saline to 5% ethanol solution. The labeling took about 60 min, with radiochemical yields (decay corrected; RCY) of 8.6% - 10% ([18F]7) and 13% - 14% ([18F]8). The RCYs were determined by TLC silica plates, with a mobile phase ethyl acetate. The retention factors (Rf) for [18F]F-, [18F]7 and [18F]8 were 0, 0.4 and 0.6. To determine radiochemical purity (RCP), analytical HPLC with a gamma ray radiodetector was used [Agilent; Gemini C18 (250 × 4.6 mm); 280 nm; mobile phase: flow rate 1 mL/min; 10 mM ammonium formate buffer(AFB)/CH3CN = 7/3]. (Retention time: [18F]5 = 3.65 min, [18F]6 = 6.68 min.)

2.3 Biodistribution studies

Saline (0.1 mL) containing [18F] tracers (370–740 Bq) was injected into the tail vein of mice bearing EMT-6 tumor. The mice (n = 3 for each time points) were sacrificed at 30 min post-injection. The organs of interest (brain, heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, muscle, bone, skin) and tumor samples were removed and weighed, and the corresponding radioactivities were assayed with an automatic gamma counter. The percentage dose per organ was calculated by a comparison of the tissue counts to suitable diluted aliquots of the injected material.

2.4 Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry analysis of blood and urine from rats

Saline (0.2 mL) containing [19F]7 (2 mg) and [19F]8 (2 mg) was injected into the tail vein of Sprague-Dawley (SD) rat. The rat was sacrificed at 30 min post injection. Urine and plasma samples were collected and analyzed by LC/MS. The LC/ MS system comprised of an Ultra-performance liquid chromatography system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) and a Quattro micro triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Micromass, Manchester, UK). The mobile phase consisted of 5 mM ammonium acetate and 2% formic acid in water (A) and acetonitrile (B). The analytes were eluted from the column by a linear gradient that increased from 5 to 50% B in 2 min, at a flow-rate of 0.4 ml/min. The composition was returned to 5% B from 2 to 3 min. The end time of the program was set at 4 min. The column was Waters ACQUITY ethylene-bridged (BEHTM) C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 μm particle size, Waters, Milford, MA, USA), the temperature of column was 30 °C. Sample volume injected was 5 μL. MS was operated in positive Electrospray ionization (ESI), the scan range was from 50 to 1000 Da, full scan mode was used to search the [19F]7, [19F]8 and their metabolites. The mass spectrometry parameters were listed as below: capillary 3.0 kV, cone 20 V, source temperature 110 °C, desolvation temperature 450 °C, desolvation gas flow 400 L/h, cone gas flow 40 L/h.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Chemical synthesis

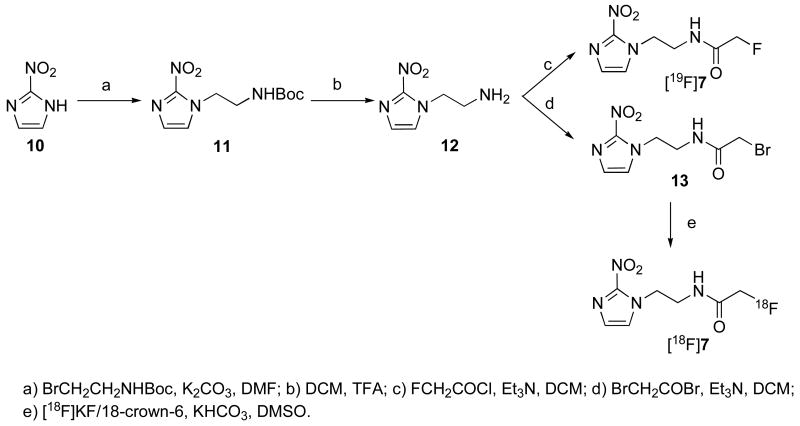

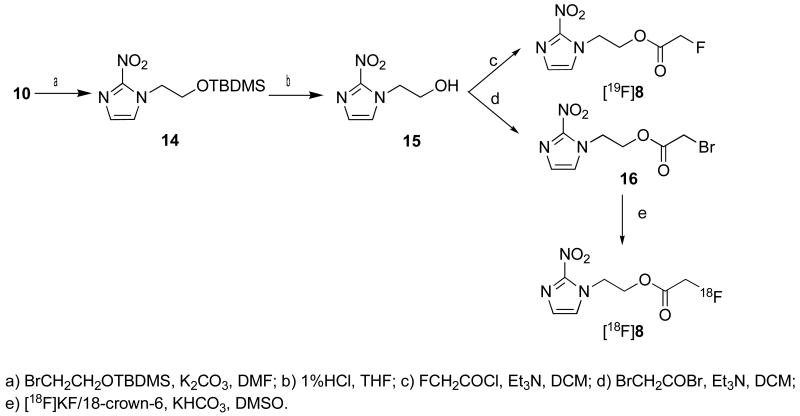

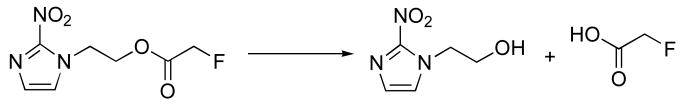

The “cold” compounds [19F]7 and [19F]8 were prepared by reactions shown in Scheme 1 and 2. Starting materials 11 and 14 were synthesized by N-alkylation of commercially available 2-nitroimdazole. The protecting group NH-Boc on compound 11 was removed by treatment with TFA to give 12. The protecting group O-TBDMS on compound 14 was removed by treatment with 1% HCl in THF to give 15. The acylation of compounds 12 and 15 with fluoroacetyl chloride and bromoacetyl bromide afforded “cold” standards - fluorinated compounds [19F]7 and [19F]8, as well as radiolabeling precursors 13 and 16, respectively.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds [19F]7 and 13

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of compounds 8 and 16.

3.2 Radiolabeling

Radiolabeling of 11 and 14 were proceeded initially with a common nucleophilic substitution reaction, using CH3CN as solvent, Kryptofix 222 (K222) as phase transfer catalyst (PTC) and K2CO3 as added metal salt for producing the “naked” 18F fluoride. However, the labeling yields of [18F]7 and [18F]8 from the fluorination reaction performed at 90 °C for 10 min were relatively low (decay corrected yield was 0 and 4-5% (n=3) for [18F]7 and [18F]8, respectively). The observed low yields were likely due to alkali instability of N-bromoacetyl compound 13 and 16 [22]. They were capable of N-alkylting the nitrogen atoms of K222 under this radiolabeling condition. By switching the PTC and metal salt to 18-crown-6 and KHCO3, [18F]7 and [18F]8 were obtained at much higher yields (decay corrected yield was 8.6%-10% and 13%-14% (n=3) for [18F]7 and [18F]8, respectively). The preparation of [18F]7 and [18F]8 took about 60 min, and the RCPs were more than 98%. The radiochemical identity was conformed by co-injection with “cold” fluorinated compounds that gave the same retention time ([18F]7 = 3.65 min, [18F]8 = 6.68 min). Purification by a solid-phase extraction (Oasis HLB cartridge) also resulted in a radiochemical pure product that had same HPLC retention time as “cold” fluorinated compound. This solid-phase extraction procedure for purification, instead of preparative HPLC method, has several advantages: the preparation was rapid and the final product was in a small volume (1.0 mL) of solvent. The procedure simplified the radiolabeling preparation and shortened the time required for radiosynthesis.

3.3 Biodistribution studies

The biodistribution studies of [18F]7 and [18F]8 (radiochemical purity > 98%) were carried out in EMT-6 tumor bearing mice (Table 1). Both compounds showed significant tumor uptakes ([18F]7: 1.55%; [18F]8: 2.35%). High physiological trace uptakes were observed in liver ([18F]7: 2.55%; [18F]8: 2.23%) and kidney ([18F]7, 2.04%; [18F]8, 2.38%). Lower activities were recorded in brain ([18F]7: 0.99%; [18F]8: 1.24) and muscle ([18F]7: 1.36%; [18F]8: 1.74%).

Table 1. Bioditrbution of [18F]NEFA ([18F]7), [18F]NEFT ([18F]8) and [18F]FMISO (1) after 30 min in EMT-6 tumor bearing mice (%dose/g; average of three rats ± S.D.).

| [18F]NEFA ([18F]7) |

[18F]NEFT ([18F]8) |

[18F]FMISO (1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| blood | 1.61±0.71 | 2.50±0.04 | 3.60±1.18 |

| brain | 0.99±0.53 | 1.24±0.12 | 2.60±0.23 |

| heart | 1.77±0.68 | 2.46±0.16 | 2.55±1.37 |

| liver | 2.55±1.65 | 2.23±0.03 | 5.54±1.08 |

| spleen | 1.59±0.82 | 1.71±0.12 | 1.54±0.25 |

| lung | 1.93±0.90 | 2.54±0.13 | 4.49±1.99 |

| kidney | 2.04±0.88 | 2.38±0.02 | 2.91±0.18 |

| muscle | 1.36±0.42 | 1.74±0.18 | 1.89±0.26 |

| bone | 1.83±0.28 | 6.29±0.34 | 2.03±0.17 |

| tumor | 1.55±0.65 | 2.45±0.08 | 3.29±0.73 |

| skin | 5.48±3.69 | 2.35±0.25 | 3.67±1.43 |

Although the uptakes of various 18F-nitroimidazloes compounds in tumor have been reported before. It's difficult to compare them due to different animal models, nature of the tumor induced and different post-injection time. However, a comparison between [18F]7, [18F]8 and commonly used PET agents [18F]FMISO (1) was made in table 1 and 2. [18F]FMISO (1) showed the expected high initial tumor uptake (3.29%, after 30 min). However, the uptakes of [18F]7 and [18F]8 in liver ([18F]7, 2.55%; [18F]8, 2.23%) were less compared to that of [18F]FMISO (1) (5.54%) with the consequence that the tumor/liver ratios ([18F]7, 0.61; [18F]8, 1.10) were higher as compared to 0.59 in [18F]FMISO (1). The tumor/blood and tumor/muscle ratios of [18F]7 and [18F]8 also compared well with those of [18F]FMISO (1). The lower uptake of normal tissues was probably because of the rapid in vivo decomposition of [18F]7 or [18F]8, which contain enzymatically or chemically labile functional groups, ie the ester or amide, which may alter the in vivo kinetics of these tracers. The enzymatic transformation of [18F]7 and [18F]8 yielded [18F]fluoroacetate, which had a rapid clearance properties [21]. Since the decrease of normal tissues uptake is an important consideration, compounds [18F]7 and [18F]8 deserve attention.

Table 2.

Comparison of tumor-to-tissue of [18F]NEFA ([18F]7), [18F]NEFT ([18F]8) and [18F]FMISO (1)

| [18F]NEFA ([18F]7) |

[18F]NEFT ([18F]8) |

[18F]FMISO (1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor/blood | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.91 |

| Tumor/liver | 0.61 | 1.1 | 0.59 |

| Tumor/muscle | 1.14 | 1.41 | 1.74 |

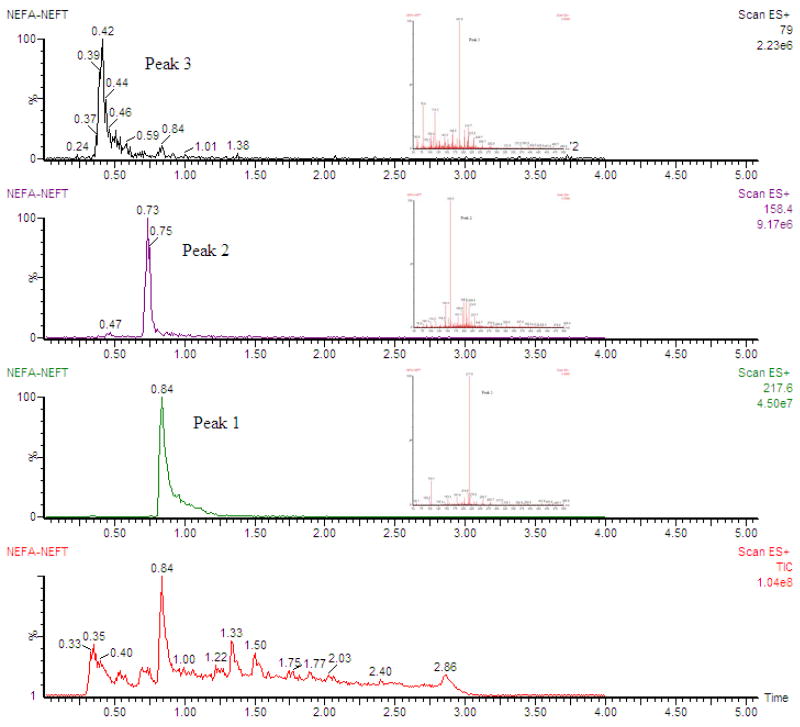

Liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC/MS) analysis of blood and urine samples from rats was performed. The metabolic profiles of [19F]7 and [19F]8 were investigated by using LC/MS, which were also used to identify the structures of metabolites. Fig. 2 was the total ion current chromatogram and the extracted ion chromatograms of metabolites of [19F]7 and [19F]8, the inserted figures were the corresponding mass spectra. A peak at 0.40 min for m/z 79, consisting with [M+H]+ for fluoroacetate, and another peak at 0.84 min for m/z 217, which matched that of [19F]7. We hypothesized the metabolite (m/z 158) found at 0.73 min was mainly generated by hydrolysis of [19F]8. Based on the data a proposed metabolic pathway for in vivo transformation of [19F]8 was listed in Scheme 3.

Fig. 2.

Extracted ion chromatograms of metabolites of [19F]NEFA ([19F]7) and [19F]NEFT ([19F]8)

Scheme 3.

A proposed metabolic pathway of [19F]NEFT ([19F]8)

According to this hypothesis, the radiometabolite of [18F]7 and [18F]8 could be [18F]fluoroacetate, which was reported as a acetate analog for prostate tumor imaging. [18F]fluoroacetate showed a rapid clearance and partial defluorination in rat [21]. This finding strongly supports that the uptake in EMT-6 bearing mice is not [18F]fluoroacetate, and it may be more likely due to the un-metabolized [18F]7 and [18F]8. It is important to note that the metabolite, [18F]fluoroacetate, may play an important role and could be responsible for the observed tumor uptake and retention. We had tried to determine the amount of this metabolite in the tumor tissue. However, in the process of evaluating the in vivo metabolism for [18F]7 and [18F]8 in the EMT-6 tumor after an iv injection. The tracers, [18F]7 and [18F]8, were not stable during the processing of the tumor tissue. The extracts of the tissue samples showed in situ ester hydrolysis of the tracers to form the [18F]fluoroacetate. Therefore, it is difficult to determine if the [18F]fluoroacetate was from in situ hydrolysis, or the [18F]fluoroacetate was transported into the tumor cells. However, as a preliminary report for this series of dual-trapping mechanisms-based tumor imaging agents, the presented information may be sufficient. Further improvements on the methods for tissue processing will be needed in the future. At this moment it is difficult to determine if the hypoxia or the trapping of the metabolite, [18F]fluoroacetate, (or perhaps both) is more important for the tumor uptake and retention.

4 Conclusion

We report herein the preparation and evaluation of two 2-nitroimidazole analogs containing enzymatically or chemically labile groups. Using the bromo precursors the labeling of these two 18F labeled 2-nitroimidazole analogs was optimized. Biodistribution studies carried out in EMT-6 tumor bearing mice showed a comparable tumor uptake and rapid clearance to those of known hypoxia imaging agent, [18F]FIMSO (1). LC/MS analysis demonstrated that [19F]7 was relatively stable in vivo. [19F]7 and [19F]8 mainly gave fluoroacetate as a metabolite. These results suggested that [18F]7 and [18F]8, containing an in vivo labile group, might be potentially useful as tumor imaging agents.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (20040027011) and Foundation of Key Laboratory of Radiopharmaceuticals (Ministry of Education) in Beijing Normal University (0511) for the financial support.

List of Abbreviations

- LC/MS

liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- [18F]FMISO (1)

[18F]Fluoromisonidazole

- [18F]FETA (2)

[18F]fluoroetanidazole

- [18F]FAZA (3)

[18F]fluoroazomycinarabinoside

- [18F]FETNIM (4)

[18F]fluoroerythronitroimidazole

- T/B

tumor-to-background

- [18F]HX4 (5)

3-[18F]fluoro-2-(4-((2-nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)propan-1-ol

- [18F]3-NTR (6)

1-[18F]fluoro-3-(3-nitro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)propan-2-ol

- [18F]NEFA (7)

2-[18F]fluoro-N-(2-(2-nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)acetamide

- [18F]NEFT (8)

2-(2-methyl-5-nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl 2-[18F]fluoroacetate

- PET

positron emission tomography

- SPECT

single photon emission comuted tomography

- TLC

Thin layer chromatography

- DMF

N,N-Dimethylformamide

- EtOAc

ethyl acetate

- TFA

trifluoracetic acid

- DCM

dichloromethane

- Et3N

triethylamine

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- K2CO3

potassium carbonate

- RCY

radiochemical yield

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- SD

Sprague-Dawley

- K222

Kryptonfix 222

- PTC

phase transfer catalyst

- NaI

sodium iodide

- Na2CO3

sodium carbonate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hoogsteen IJ, Marres HAM, van der Kogel AJ, Kaanders JHAM. The hypoxic tumour microenvironment, patient selection and hypoxia-modifying treatments. Clin Oncol. 2007;19:385–96. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray LH, Conger AD, Ebert M, Hornsey S, Scott OC. The concentration of oxygen dissolved in tissues at the time of irradiation as a factor in radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 1953;26:638–48. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-26-312-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters LJ, Withers HR, Thames HD, Jr, Fletcher GH. Tumor radioresistance in clinical radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1982;8:101–8. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(82)90392-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaupel P, Mayer A. Hypoxia in cancer: significance and impact on clinical outcome. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:225–39. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strauss LG, Conti PS. The applications of PET in clinical oncology. J Nucl Med. 1991;32:623–48. discussion 49-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballinger JR. Imaging hypoxia in tumors. Semin Nucl Med. 2001;31:321–9. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2001.26191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucignani G. PET imaging with hypoxia tracers: a must in radiation therapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:838–42. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krohn KA, Link JM, Mason RP. Molecular imaging of hypoxia. J Nucl Med. 2008;49 2:129S–48S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman JD, Franko AJ, Sharplin J. A marker for hypoxic cells in tumors with potential clinical applicability. Br J Cancer. 1981;43:546–50. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1981.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varghese AJ, Whitmore GF. Binding to cellular macromolecules as a possible mechanism for the cytotoxicity of misonidazole. Cancer Res. 1980;40:2165–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasey JS, Koh WJ, Grierson JR, Grunbaum Z, Krohn KA. Radiolabeled fluoromisonidazole as an imaging agent for tumor hypoxia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17:985–91. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasey JS, Grunbaum Z, Magee S, Nelson NJ, Olive PL, Durand RE, Krohn KA. Characterization of radiolabeled fluoromisonidazole as a probe for hypoxic cells. Radiat Res. 1987;111:292–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koh WJ, Rasey JS, Evans ML, Grierson JR, Lewellen TK, Graham MM, Krohn KA, Griffin TW. Imaging of hypoxia in human tumors with [F-18]fluoromisonidazole. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;22:199–212. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)91001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham MM, Peterson LM, Link JM, Evans ML, Rasey JS, Koh WJ, Caldwell JH, Krohn KA. Fluorine-18-fluoromisonidazole radiation dosimetry in imaging studies. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1631–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang DJ, Azhdarinia A, Kim EE. Tumor specific imaging using Tc-99m and Ga-68 labeled radiopharmaceuticals. Curr Med Imaging Rev. 2005;1:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang DJ, Wallace S, Cherif A, Li C, Gretzer MB, Kim EE, Podoloff DA. Development of F-18-labeled fluoroerythronitroimidazole as a PET agent for imaging tumor hypoxia. Radiology. 1995;194:795–800. doi: 10.1148/radiology.194.3.7862981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groenroos T, Bentzen L, Marjamaeki P, Murata R, Horsman MR, Keiding S, Eskola O, Haaparanta M, Minn H, Solin O. Comparison of the biodistribution of two hypoxia markers [18F]FETNIM and [18F]FMISO in an experimental mammary carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:513–20. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sorger D, Patt M, Kumar P, Wiebe LI, Barthel H, Seese A, Dannenberg C, Tannapfel A, Kluge R, Sabri O. [18F]Fluoroazomycinarabinofuranoside (18FAZA) and [18F]Fluoromisonidazole (18FMISO): a comparative study of their selective uptake in hypoxic cells and PET imaging in experimental rat tumors. Nucl Med Biol FIELD Full Journal Title:Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2003;30:317–26. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piert M, Machulla HJ, Picchio M, Reischl G, Ziegler S, Kumar P, Wester HJ, Beck R, McEwan Alexander JB, Wiebe Leonard I, Schwaiger M. Hypoxia-specific tumor imaging with 18F-fluoroazomycin arabinoside. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:106–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasey JS, Hofstrand PD, Chin LK, Tewson TJ. Characterization of [18F]fluoroetanidazole, a new radiopharmaceutical for detecting tumor hypoxia. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1072–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barthel H, Wilson H, Collingridge DR, Brown G, Osman S, Luthra SK, Brady F, Workman P, Price PM, Aboagye EO. In vivo evaluation of [18F]fluoroetanidazole as a new marker for imaging tumour hypoxia with positron emission tomography. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2232–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Loon J, Janssen MHM, Oellers M, Aerts HJWL, Dubois L, Hochstenbag M, Dingemans AMC, Lalisang R, Brans B, Windhorst B, van Dongen GA, Kolb H, Zhang J, De Ruysscher D, Lambin P. PET imaging of hypoxia using [18F]HX4: a phase I trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1663–68. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1437-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bejot R, Kersemans V, Kelly C, Carroll L, King RC, Gouverneur V. Pre-clinical evaluation of a 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazole analogue of [18F]FMISO as hypoxia-selective tracer for PET. Nucl Med Biol. 2010;37:565–75. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponde DE, Dence CS, Oyama N, Kim J, Tai YC, Laforest R, Siegel BA, Welch MJ. 18F-fluoroacetate: a potential acetate analog for prostate tumor imaging-in vivo evaluation of 18F-fluoroacetate versus 11C-acetate. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:420–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mori T, Sun LQ, Kobayashi M, Kiyono Y, Okazawa H, Furukawa T, Kawashima H, Welch MJ, Fujibayashi Y. Preparation and evaluation of ethyl [(18)F]fluoroacetate as a proradiotracer of [(18)F]fluoroacetate for the measurement of glial metabolism by PET. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:155–62. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]