Abstract

Wellness Self-Management (WSM) is a recovery-oriented, curriculum-based, and educationally focused practice designed to assist adults with serious mental health problems to make informed decisions and take action to manage symptoms effectively and improve their quality of life. WSM is an adaptation of the Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) model, a nationally recognized best practice for adults with serious mental health problems. WSM uses comprehensive personal workbooks for group facilitators and consumers and employs a structured and easy-to-implement group facilitation framework. Currently, more than 100 adult mental health agencies are implementing WSM, representing a broad array of program types, clinical conditions, and cultural populations. The authors describe the development, key features, delivery, adoption and sustaining of WSM

I. INTRODUCTION: STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

Despite the existence of effective, research-supported treatments for adults with severe mental illness, these practices are rarely implemented and sustained in real-world settings. (1). Over the last several decades, research has identified a number of interventions that can provide significant symptom relief and improve overall functioning (2–3). All too often effective medication and psychosocial treatment options do not find their way to those who could benefit from them. Although our knowledge of best practices for individuals with serious mental health problems is impressive and continues to grow, our understanding of how to promote the widespread adoption of new practices that are sustainable over time lags far behind (4).

The challenges faced by mental health systems to implement, sustain, and spread quality practices are numerous and daunting. Challenges include staff turnover, demands on workforce competencies, inadequate clinical supervision, fiscal viability, real or imagined risks associated with change, role demands, and a lack of accessible and practical resources (5–6).

This past decade has witnessed an increase in efforts to address a number of these challenges and explore strategies to bring recovery-oriented best practices to the field. One example of this has been the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) national best practices implementation project initiated in 2001 with eight States, including New York State (7).

II. THE NEW YORK STATE EXPERIENCE

In 2002–2005, the New York State (NYS) Office of Mental Health (OMH) participated in the national SAMHSA pilot initiative to study the impact of a specific implementation strategy for promoting the adoption of best practices. This strategy involved the use of consultants/trainers and “resource kit” materials. One of the best practices selected by OMH to pilot in NYS was Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) (8). IMR is a curriculum-based treatment using research-informed psychosocial approaches that help adults to manage serious mental health problems successfully and make progress towards specific goals.

NYS implemented IMR in three community agencies in NYC and a mental health unit in a prison. As these sites implemented IMR, the consultants/trainers observed the implementation process and gathered feedback from practitioners, consumers, and program leadership. Overall, stakeholders reported that IMR added value to the quality of services. Administrators and staff commented that the structured materials and handouts, along with a manual that emphasizes core clinical competencies, was a useful resource. Feedback also suggested ways in which IMR could be expanded and adapted to increase its widespread usability and sustainability, especially when delivered in groups. Although IMR may be employed in a group modality, it was primarily designed to be used in individual sessions. The importance of adapting IMR for group work was based on two considerations: 1) the recognized benefits of group treatment and peer learning for people with serious mental health problems and 2) group treatment is a mainstay for the majority of mental health programs in NYS.

The consultants/trainers engaged a NYS operated facility (Hudson River Psychiatric Center) and ten member agencies of the Urban Institute for Behavioral Health (UIBH), a consortium of NYC providers committed to implementing evidence-based practices, to explore field testing and evaluating adaptations to IMR based on our observations and stakeholder experiences. This led to adaptations in the practice and ultimately to a new name: Wellness Self-Management (WSM) (9). Extension 1

III. WSM AND IMR: SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES

WSM shares much in common with IMR including the use of a structured comprehensive curriculum that includes topics that address recovery, relapse prevention, coping and stress management, social supports, practical facts about mental health problems, medication information, problem solving and personal goal development. WSM and IMR also place an emphasis on assisting participants to apply their learning in vivo. Both approaches reflect recovery oriented values and principles involving self direction, choice, and shared decision making.

The ways in which WSM departs from IMR includes organizing the entire curriculum into a workbook that belongs to the participants, adding a physical health chapter, using self directed action steps, organizing the process around a specific group facilitation format and embedding core competencies within the workbook. These adaptations were designed to facilitate the use of the curriculum in a group modality and to promote the widespread implementing and sustaining of these services across New York State. (Extension 2)

IV. METHODS TO PROMOTE THE WIDESPREAD IMPLEMENTING, SUSTAINING, AND SPREADING OF WSM THROUGHOUT NYS

Following a yearlong field testing of the WSM workbook and group format, OMH funded the Center for Practice Innovations at Columbia Psychiatry to design a statewide effort to promote the adoption and sustaining of WSM. Employing a formal learning collaborative methodology, based on the quality improvement approach of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) (10), over 100 mental health service agencies voluntarily joined this effort and contributed $500.00 towards the purchase of WSM workbooks which cost approximately $10.00 each. The range of program types is extensive and includes virtually every type of mental health treatment setting including the mental health units located within prisons. WSM workbooks were also translated into Spanish, Chinese and Korean to accommodate programs serving these populations.

All agencies agreed to implement WSM and report data related to key performance indicators including attendance, discontinuations and reasons why, client self assessment of progress and group leader ratings of each group participants degree of involvement and goal progress. In addition, practice fidelity was determined in two ways: ratings of WSM group leaders by supervisors and by an independent research assistant. (Extension 3)

V. FINDINGS

Findings indicate that WSM groups are well attended and that the most common reason for participants to discontinue is discharge from the agency. Group leaders generally implement the group with fidelity. Across the state, the median fidelity ratings completed by the participating program supervisors was 50 out of a possible total score of 58. We also employed a separate independent fidelity measure that focused on group skills with a sample of programs. These fidelity ratings (median score of 18 out of a maximum score of 24) further indicated that most practitioners employ the workbook and group format at a satisfactory level.

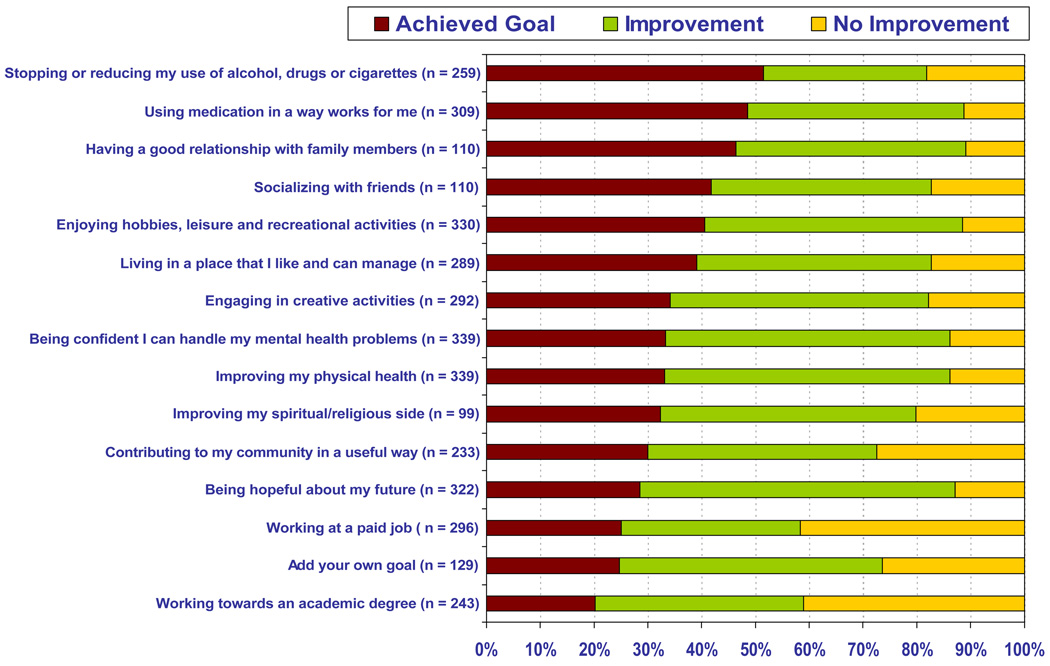

At the beginning of the group, participants identified personally meaningful goals. When completing the program, participants rated their progress in terms of how well they improved or attained their goals (see Figure 1). Reports from participants and group leaders indicates that 75 % of participants show significant progress with respect to consumer identified goal areas over the course of the program.

Figure 1. Personal Assessment of Progress at the End of the WSM Program.

At the beginning of the WSM program, each participant selected goals on which he/she wanted to work. At the end of the program, participants reported what progress they made on those goals since the start of the program. We report the results from 409 group participants.

An important outcome of this initiative was to determine the sustainability of WSM following the conclusion of the formal learning collaborative in October 2009. A recent survey conducted 10 months later was responded to by 87 of the original 100 participating agencies. The responses indicated that 85% currently provide WSM groups; 13 % have plans to offer WSM in the near future with only one program reporting difficulty sustaining WSM due to serious client transportation problems.

Empowering agencies to sustain WSM on their own was accomplished by creating inexpensive and easily accessible staff training resources such as a free online course on how to conduct a WSM group program, promotional and training DVD’s, downloadable workbooks, group leader training guides and informational brochures.

The positive response of agencies to the WSM initiative has also resulted in numerous requests from providers for additional curriculum based resources addressing the needs of adolescents/young adults, adults with co-occurring substance use disorders and mentally ill prison inmates. Several initiatives are currently underway to field test WSM related workbooks designed to address the needs of these three populations. We expect to report on the outcomes of these efforts in the coming year.

The Center for Practice Innovations website at www.practiceinnovations.org will provides interested practitioners, programs or agencies the information, tools and resources needed to successfully implement WSM in groups.

VI. CONCLUSIONS

New York’s statewide initiative built upon and reflected the core principles of a recognized best practice, while making adaptations and creating tools and resources to promote the widespread adoption and sustaining of this practice in response to multi-stakeholder feedback. New York’s aim is to go beyond the initial implementation phase and design strategies to empower organizations to sustain and spread a practice that adds value to the mental health system and is applicable across clinical conditions, cultural populations, and program types. Developing and evaluating user-informed adaptations along with the creation of easily accessible tools and resources may point the way to closing the research-to-services gap.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Ganju V. Implementation of best practices in state mental health systems: implications for research and effectiveness studies. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2003;29:125–131. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, Dickerson FB, et al. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36:94–103. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Achieving the promise: Transforming mental health care in America. Final report. 2003 DHHS Publication No. SMA 03–3832.

- 4.Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blasé KA, et al. Tampa, F.L.: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network; 2005. Implementation Research: A Synthesis of the Literature. (FMHI Publication #231) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mancini AD, Moser LL, Whitley R, et al. Assertive Community Treatment: Facilitators and Barriers to Implementation in Routine Mental Health Settings. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:189–195. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woltmann EM, Whitley R, McHugo GJ, et al. The Role of Staff Turnover in the Implementation of Best practices in Mental Health Care. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:732–737. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.7.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drake RE, Goldman HH, Leff HS, et al. Implementing Evidence-Based Practices in Routine Mental Health Service Settings. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:179–182. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueser K, Gingerich S. Illness Management & Recovery Implementation Resource Kit. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salerno A, Margolies P, Cleek A. Wellness Self-Management Personal Workbook. Albany, NY: New York State Office of Mental Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.IHI Innovation Series white paper. Boston: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2003. The Breakthrough Series: IHI’s Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.