Abstract

Wraparound is an individualized, team-based service planning and care coordination process intended to improve outcomes for youth with complex behavioral health challenges and their families. In recent years, several factors have led wraparound to become an increasingly visible component of service systems for youth, including its alignment with the youth and family movements, clear role within the systems of care and public health frameworks, and expansion of the research base. In this paper, we provide a review of the place of the wraparound process in behavioral health, including a discussion of the opportunities it presents to the field, needs for further development and research, and recommendations for federal actions that have the potential to improve the model’s positive contribution to child and family well-being.

Keywords: Wraparound, Care management, Community-based, Policy, Children and adolescents, Effectiveness, Systems of care

With the recent change in presidential administrations and ongoing scrutiny of the nature of our nation’s health care system, it is incumbent upon those of us who work in the arena of children’s mental health to take stock of recent research and promising frameworks, in the name of improving our policies and practices. It is true that it has become standard operating procedure to preface articles on children’s mental health with a recitation of bad news— that the children’s mental health system is “in shambles” and getting worse (Knitzer 1982; New Freedom Commission on Mental Health 2003; Tolan and Dodge 2005), that access to services for youth with mental health problems is limited (Huang et al. 2004; US Department of Health and Human Services 2005a), and that when it is provided, the services will be unlikely to be based on current evidence of what will be most effective (Hoagwood et al. 2001). Moreover, when a child’s needs are complex and overlapping, services are not likely to be coordinated across key providers and helpers and/or engaging of parents, teachers, family members, and the youth themselves (McKay and Bannon 2004; New Freedom Commission 2003; Stroul and Friedman 1994). And, for many youth, the result is all too often placement in restrictive out-of-community placements, use of which continues to increase nationally despite a lack of evidence for their long-term effectiveness (Burns et al. 1998; Farmer et al. 2004).

While all of this may be true, we are poised at a moment in history in which health care reforms are being proposed, access to care is being emphasized, and coordination of care for specialty mental health populations has become a focal point for change efforts. Recognizing the considerable work that has been done in children’s mental health over the past 25 years and with an eye toward the future, we present reason for optimism and a belief that research and practices exist that can inform new approaches and policies. In this paper, we take a fresh look at the wraparound philosophy and intervention model, to understand its role in children’s mental health systems. In the pages that follow, we will review the place of the wraparound process in behavioral health and discuss related systems changes that accompany successful wraparound implementation. We conclude with a discussion of the opportunities and challenges presented by the wraparound model, and recommendations for federal actions that have the potential to improve the likelihood of wraparound’s positive contribution to improving the well-being of youth with the most serious behavioral and emotional needs and their families.

The Wraparound Process

Wraparound has been described variously as a philosophy, a process, an approach, and a service. As it is currently conceived, wraparound is an individualized, family-driven and youth-guided team planning process that is underpinned by a strong value base that dictates the manner in which services for youth with complex needs should be delivered (similar to system of care values; Stroul and Friedman 1994). Wraparound can also be described with respect to the types of system and program conditions that are necessary to facilitate model adherent implementation. These necessary system and programs conditions recognize that, though wraparound has historically been delivered on an individual basis, it is most likely to be faithfully implemented (and effective for youth and families) within a hospitable system that includes a care management model that can support the wraparound values and principles across all services delivered in the system. When implemented in this context, wraparound can help overcome common barriers to accessing effective services and supports for youth with multiple needs and/or multiple agency involvement. In the rest of this introductory section, we will summarize each of these components of the wraparound model in turn.

Value Base

Wraparound represents a philosophy and value base which has been presented fairly consistently over the past 25 years and has recently been distilled into a set of ten principles (Bruns et al. 2008). This value base explicitly dissents from more traditional service delivery conceptualizations, in which a professional, viewed as the source of primary expertise, singlehandedly creates a treatment plan based on a diagnosis and/or enumeration of deficits. The value base also deviates from more traditional approaches by emphasizing an ecological model, including consideration of the multiple systems in which the youth and family are involved, and the multiple community and informal supports that might be mobilized to successfully support the youth and family in their community and home.

In the wraparound process, a dedicated care coordinator works together with the family and youth (if developmentally appropriate) to identify the strengths, needs, and potentially effective strategies, culminating in a single, coordinated, individualized plan of care. It is in the facilitation of this planning process that the wraparound guiding principles are operationalized. Thus, two guiding principles of wraparound include family and youth voice and choice and team based. These two principles are actualized through the planning process in which families and youth are given intentional priority in decision making and are equal partners within the team structure1. The wraparound plan of care typically includes formal services that are balanced with natural supports such as interpersonal support and assistance provided by friends, kin, and other people drawn from the family’s social networks. The additional principles of collaboration, cultural competence, strengths based, and outcome based are all achieved and actualized through the team process with team members working cooperatively and sharing responsibility for a single plan of care, even when multiple providers are involved. The principle of unconditional support is achieved through wraparound teams not giving up on, blaming, or rejecting the youth or family, even in the face of significant needs and challenges.

After family and youth voice and choice, perhaps the most important and enduring principles of wraparound are those of individualized and community-based. When implemented fully, the wraparound process results in a set of strategies and services provided in the most inclusive and least restrictive settings possible. These strategies are tailored to meet the unique and holistic needs of the youth and family, including supports to family members to reduce stress and to ensure that services are accessed and treatments completed by the identified youth. As described by VanDenBerg (2008), “the more complex the needs of the child and/or family, the more intensive the individualization and degree of integration of the supports and services around the family” (p.5). Thus, in the wraparound model, child, youth, and family needs drive access to services and the intensity of service integration, not the restrictiveness of services.

Practice Model

For a number of years, wraparound was described primarily in terms of the above principles, and thus it was probably appropriate to conceive of it as an approach (i.e., an overall orienting view based on global concepts; Kazdin 1999). However, as initial program descriptions (e.g., Burchard et al. 1993; VanDen Berg and Grealish 1996) and evaluations of wraparound’s potential for positive impact (e.g., Burchard and Clarke 1990) emerged, and implementation efforts accelerated, researchers and implementers alike recognized the need to better define the practice model (Clark and Clarke 1996; Walker et al. 2008). As a result, several model-specification efforts were undertaken between 1998 and 2004. The latest of these involved a review of programs with evidence for impact and a multistage consensus process that employed the Delphi decision-making process (see Walker and Bruns 2006; Walker et al. 2008).

The model that resulted, and on which much wraparound implementation nationally is now based (Bruns et al. 2009), describes 32 activities, grouped into four phases: Engagement and Team Preparation, Initial Plan Development, Plan Implementation, and Transition. As families and youth move through these phases, the care coordinator or wraparound facilitator (often along with a trained family partner) undertakes a strengths-based, non-judgmental engagement and planning process that includes crisis stabilization; orientation to the wraparound process; an elicitation of family and youth strengths, culture, and vision for the future; discussion of treatments and strategies that have been successful in the past; and identification of individuals who play key roles in the life of the youth and family (including extended family and community resources). As the team continues to support the family and youth, commonly observed barriers to effective treatment for youth and families are addressed, crises that may interfere with treatment planning and follow through are stabilized, and caregivers are provided with support (such as through access to the family partner) that encourages the development of an alliance between helpers and family members.

In the Implementation phase of the wraparound process, the team meets, frequently at first, to review the status of the plan and indicators of progress toward the priority goals, and the facilitator supports the family and team members to ensure that service and support strategies are implemented. Transition out of formal wraparound is intended to occur when the team (with primary guidance from the family) agrees that the priority needs that brought the youth and family into the process have been met and/or the vision for the future of the family is being achieved. Thus, the wraparound process does not have a set timeframe for completion, though programs and initiatives may set such guidelines or benchmarks.

Necessary System Structures for Wraparound

As summarized above, wraparound can be described in terms of a practice model, with staff being trained and supervised to effectively perform their roles, provider organizations hosting these individuals, and so forth. At the same time, system reform is usually required for wraparound to work well. Research and experience has shown that there are a number of system-level conditions that need to be in place to support wraparound implementation at the ground level (Bruns et al. 2006; Walker et al. 2003). One obvious example is that, since wraparound is not a clinical treatment, the behavioral health system must be able to provide wraparound-enrolled youth and families with access to effective treatments and ancillary supports. Without access to a range of effective clinical treatments and supports (e.g., mentors, in-home behavioral support services, respite), wraparound teams will find it more difficult to effectively strategize to meet the full range of youth and family needs.

Other types of system supports that are required include ensuring that personnel are trained and well-supervised to serve their roles on teams, monitoring the quality of wraparound implementation, and tracking outcomes for youth and families. In addition, fiscal structures are required that can ensure model-adherent wraparound implementation (including, for example, the ability of teams to flexibly purchase needed services and supports). To achieve these conditions, communities often find it necessary to create some kind of collaborative, cross-agency governance structure. Such “community teams” also help ensure that the initiative has well-understood goals and a clearly identified population of focus, including eligibility requirements. Community teams can also support implementation by convening high-level leadership of different child-serving agencies. These leaders can then support wraparound implementation by contributing resources to the wraparound initiative, designing effective referral mechanisms, establishing memoranda of agreement that span agencies, and shaping the behavior of staff (e.g., child welfare case workers and juvenile probation officers) so they will participate in wraparound implementation in ways that are in keeping with the principles.

Thus, in addition to the value base and implementation procedures, current conceptualizations of wraparound include an implementation “blueprint” that specifies a set of key areas in which system- and program-level structures and procedures must be established. These areas have been enumerated based on research (Walker et al. 2008; 2003), and have been represented in terms of six themes: (1) community partnership, (2) collaborative action, (3) fiscal structures, (4) service array, (5) human resource development, and (6) accountability. This “blueprint” for wraparound implementation supports is somewhat similar to that described for the systems of care framework (e.g., Pires 2002). The difference, however, is that the systems of care model presents an “organizing framework and value base” (Stroul 2002; p. 4) for structuring an overall system. In contrast, the wraparound process is intended for use with a smaller segment of the population (i.e., children and youth with very complex needs), and is an intervention that has specific implementation requirements.

Care Management Models

An increasingly common method for organizing a system so that it can achieve the wraparound principles in service delivery is through creation of care management models. Such models are one response to the reality that youth with complex behavioral health needs and their families typically are involved with multiple providers and systems. Because a single provider or system rarely can respond comprehensively to the constellation of needs of these youth and families, new technologies have emerged in children’s services that create one “locus of accountability” for youth and families involved in multiple systems. These technologies, which support the organization, management, delivery and financing of services and supports across multiple providers and systems, are implemented through a Care Management Entity (CME) structure (Maryland Child and Adolescent Innovations Institute and Mental Health Institute 2008).

A CME is responsible for developing and implementing comprehensive individualized plans of care (i.e., wraparound plan or service plan) for each participating youth and his or her family. These plans are developed through a wraparound practice approach and driven by the needs of the individual youth and family rather than by the boundaries of discrete programs, agencies or funding systems. This plan does not replace the individual treatment plans developed for individual service delivery but rather unites them in a single document that is comprehensive and action-oriented. The wraparound process is used to implement the care coordination process provided by the CME, with fidelity to the wraparound principles and its practice model evaluated by a neutral party. Ultimately, the CME ensures accountability to an individual and his or her family and plan of care through individualized planning, utilization management, and coordination of services, resources and supports, with objective outcome measures mutually determined across multiple providers and systems in partnership with the youth and family (Maryland Child and Adolescent Mental Health Institute and Innovations Institute 2008).

Wraparound Implementation Nationally

As a nation, we may well invest more in implementing “wraparound”-like processes than any other specific community-based model aimed at youth with serious emotional and behavioral health problems. A recent survey of state mental health directors found wraparound projects in 43 of 49 states and territories that responded, with over half of all states reporting some type of statewide wraparound initiative. This survey yielded an estimate of 98,000 youth enrolled in over 800 wraparound initiatives in the United States (Bruns et al. 2008). By comparison, established evidence-based treatments such as Functional Family Therapy (FFT; Alexander and Sexton 2002), Multisystemic Therapy (MST; Henggeler et al. 1998), and Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (Chamberlain and Smith 2003) serve only about 30,000, 19,000, and 1,200 youths, respectively (Evidence Based Associates 2008).

At the same time, however, these numbers must be put into full context. First, upwards of 4–7.5 million youth are estimated to experience a serious emotional disturbance (Friedman et al. 1999), meaning that very few receive one of these intensive community-based interventions. Second, the number of youths served in residential treatment settings annually was recently estimated at 211,000 across child welfare, mental health, substance abuse, and juvenile justice (US GAO 2008), which dwarfs the number of youth served by any of these defined community-based models (even taking into account the potential duplication of youth across populations). With respect to expenditures, the $4.2 billion annual cost of maintaining the country’s estimated 34,000 mental health- and substance abuse-specific residential treatment center beds is also likely far higher than for these community-based models combined (Cooper et al. 2008). Thus, even as we face a critical need to facilitate greater availability and access to appropriately intensive community-based services, we also must recognize the influence of the wraparound philosophy and practice model nationwide.

The importance of wraparound in children’s behavioral health can be appreciated by reviewing the efforts of states undertaking large-scale system reform efforts for children with serious emotional problems that include wraparound components. Many of these state initiatives have resulted from lawsuits challenging states’ failure to provide comprehensive and necessary behavioral health treatments to children with serious emotional disturbance in their homes and/or communities. Recent examples include class-action lawsuits such as Rosie D. versus Romney in Massachusetts, JK versus Eden in Arizona, and Katie A. versus Bonta in California, settlements of all of which have directed states to provide individualized, team-based, service coordination via some expression of the wraparound process to thousands of children and youth who are the members of the class. Though implementation of these settlement plans has been challenging due to cost and strategic planning issues, they have indisputably been drivers of major change efforts for children’s behavioral health systems.

In other states, legislation has led to implementation or expansion of wraparound. In 1997, well before the settlement of Katie A versus Bonta, California Senate Bill 163 enabled California counties to develop the wraparound model as an alternative to group homes, using state and county Aid to Families with Dependent Children-Foster Care funds. Monthly case rates average approximately $5,000 per month, from which providers must subtract costs of any out-of-home placements. As of 2006, 31 of 56 California counties have adopted such plans (California Department of Social Services 2008, 2009). Other states include Nevada, which in 2005 legislated funding to provide comprehensive wraparound services for over 300 children annually in the child welfare system; and Washington, which in 2008 passed a children’s mental health bill approving, among other things, implementation of new wraparound initiatives. In Oregon, legislation requiring that a certain percent of program dollars support evidence-based approaches, combined with the inclusion of wraparound on the list of approved practices, has encouraged implementation. Kansas, Colorado, Florida, and New Jersey are among a number of other states where legislation has encouraged implementation of wraparound by promoting or requiring cross-agency collaboration, more flexible use of agency specific dollars, and/or adoption of system of care principles.

Though lawsuits and legislation have encouraged implementation in many states, local and state system reform efforts have historically provided the majority of fuel to the wraparound vehicle. These include longstanding and frequently-cited efforts such as those in Indiana (Anderson et al. 2003) and Milwaukee County, Wisconsin (Kamradt 2000; Kamradt et al. 2008), as well as major new initiatives in Maryland, Pennsylvania, Oklahoma, Maine, and elsewhere. Meanwhile, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has recently increased its allocation to its Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children and Their Families (CCMHS) program, which has provided over one billion dollars to nearly 150 “system of care” grantee communities nationally, and which encourages use of wraparound in its funded sites (US Department of Health and Human Services 2005b).

Wraparound’s Current Status in Children’s Behavioral Health

With this level of state, federal, and local investment of increasingly scarce and restricted resources, it is important to scrutinize what is driving such widespread deployment of the wraparound model, and to ask whether it is justified. As discussed in the section that follows, expansion of the implementation of the wraparound process has historically been explained as much by its alignment with the major frameworks and movements that currently drive children’s mental health as by the level of development of its evidence base. Specifically, wraparound aligns strongly with the consumer and family movement, fills an increasingly notable gap in the continuum of care proposed by the public health framework, and serves a central role in the application of the systems of care framework. More recently, the procedures of the wraparound process have been better operationalized and codified, and the model has gained support from an expanding evidence base. Both of these developments have enhanced wraparound’s status when viewed through the lens of the evidence-based practice movement; however, more progress will be needed before wraparound can be promoted on the strength of the research evidence alone.

Alignment with the Family and Youth Movements

Over the past 25 years, the evolution of thinking in the field of children’s mental health has been profoundly shaped by the emergence of the family movement. During this period, local-, state-, and national-level family-run organizations emerged and grew steadily in membership and visibility. Family organizations used their increasing strength to advocate for system reform, and to promote a profound reconceptualization of the relationship between service providers and the families or other caregivers of children experiencing mental health difficulties (Flynn 2005; Hoagwood 2005). More recently, the youth movement has championed the engagement of youth fully in their own care. Like caregivers, youth are also viewed as experts based on their knowledge of themselves and their personal experiences within the child- and youth-serving systems. Largely because of the work of families, youth, and their allies, the traditional view of professional as expert and child and family as target of treatment has been gradually changing, and there has been increasing recognition of caregivers and youth as experts about services, supports, and treatment strategies that are likely to be successful (Malysiak 1998; Matarese et al. 2008; Osher et al. 2008; Rosenblatt 1996).

The rapid expansion of the family and youth advocacy movements has contributed to the growing popularity of wraparound. Family organizations are often strong supporters of wraparound because its philosophy of care stresses family empowerment and highlights the importance of building and strengthening families’ social and community ties. As described above, the wraparound principle of “family voice and choice” unequivocally emphasizes the central role that families play in making decisions throughout the wraparound process. Family members also played a significant role in defining the wraparound practice model (Walker et al. 2008), particularly with regard to defining the role of family peer support partners in wraparound (Penn and Osher 2008). Similarly, the grassroots youth movement that led to the development of the national organization Youth Motivating Others through Voices of Experience (Youth M.O.V.E.; Matarese et al. 2008) has also facilitated young people becoming actively involved in enhancing the wraparound practice model through integration of youth support partners. Youth and family members’ participation in designing aspects of the wraparound model has substantially contributed to their positive regard for wraparound and to their enthusiasm for making wraparound more broadly available.

Public Health Approaches

As promoted by the President’s New Freedom Commission Report (2003) and summarized by Cooper et al. (2008), the public health framework for children’s behavioral health advocates for a population-based approach, supporting a continuum of activities from health promotion and prevention through early intervention and treatment. According to this conceptualization, at the far end of the continuum, care coordination for youth should be available to youth with the most complex needs (Cooper et al. 2008). Similarly, Weisz et al. (2005) have described the need for a continuum of available programs and resources for children and youth that range in intensity from indicated prevention to time-limited therapy to “enhanced therapy.” At the far end of this continuum, “continuing care” is defined as supporting “effective living in individuals diagnosed with persistent, long-term conditions” (Weisz et al. 2005; p. 632). Strategies used in continuing care include multi-modal interventions that combine elements such as family support, parent and youth skill-building, and coordination with school, community, and medical resources.

Whether conceived as a need for “care coordination” or “continuing care,” public health frameworks for children’s mental health are increasingly specific in their description of the essential importance of approaches for combining and coordinating multiple services and supports, to ensure that children and youth with the most complex needs can “live effectively” in their homes and communities. At the same time, this level and type of treatment has the fewest options and the least well-developed research base (Weisz et al. 2005). Continuing care or multi-modal approaches cited by Weisz et al. (2005) include models specific to autism (e.g., Lovaas and Smith 2003), early onset bipolar disorder (e.g., Fristad et al. 2003), and juvenile offending and substance abuse problems (Alexander and Sexton 2002; Henggeler et al. 1998; Chamberlain and Smith 2003). Given the paucity of research overall, and the fact that the models available target a rather narrow range of disorders, it is perhaps not surprising that those working within the public health framework and looking for evidence-based or promising “continuing care” models for youth with persistent and complex emotional and behavioral problems often consider developing capacity to implement the wraparound process.

The System of Care Framework

As described above, arguably the federal government’s greatest single investment in children’s mental health of the past 15 years has been promotion of the system of care framework (Pires 2002; Stroul and Friedman 1994). According to this framework, child-serving systems must exert intentional, cross-system effort to ensure two main system outcomes: That services are family-driven, community-based, and culturally and linguistically competent; and that mechanisms and functions are put in place that can promote achievement of these values, such as a full range of necessary community-based services and supports, single plans of care for youth, effective transitions to adulthood, and care coordination for youth with complex needs. Though the system of care framework has been critiqued for the small number of youth served by the federal grant program (Cooper et al. 2008) and a lack of rigorous research (Weisz et al. 2006), evaluation results show promising outcomes for participating youths and families (Manteuffel et al. 2008), and there can be little doubt that the system of care framework has been influential in shaping how children’s services are delivered nationally.

Given the framework and its prescribed components, it is not surprising that the wraparound process has been described as “the most commonly articulated aspect of practice within systems of care” (Cook and Kilmer 2004; p. 657). Indeed, the wraparound process and the system of care framework have been closely related historically and philosophically, to the point that the two concepts have been persistently conflated (Walker et al. 2008). In recent years, however, distinctions between the two have become better articulated, with the wraparound process presented as a mechanism through which care planning and coordination can be provided to youth with the most serious and complex needs in a way that is consistent with the system of care principles and that perpetuates and supports system of care reform efforts (see Pires 2002; Stroul 2002; Walker et al. 2008).

Status of the Wraparound Evidence Base

The most common characterization of the research base on the wraparound process has tended to be “promising” (Burns et al. 1999; National Advisory Mental Health Council 2001; New Freedom Commission on Mental Health 2003). At the same time, perhaps because of its alignment with many major movements in children’s mental health (described above), this characterization has apparently been deemed adequate for wraparound to be included in Surgeon General’s reports on both Children’s Mental Health and Youth Violence (US Department of Health and Human Services 1999, 2000), cited extensively as an option for use in federal grant programs (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2005a, b), and presented by many leading researchers as a potential mechanism for improving the uptake of evidence-based practices for children and adolescents with serious emotional and behavioral disorders (Friedman and Drews 2005; Tolan and Dodge 2005; Weisz et al. 2006). Practitioners also seem to perceive that wraparound is an effective practice; a recent survey of providers found that wraparound was the second-most frequently identified “evidence based” intervention (after cognitive behavior therapy) by service providers (Sheehan et al. 2007).

At the same time, most external reviewers have suggested that significant improvement is needed in the wraparound research base before wraparound can be promoted on the basis of firm empirical evidence. Bickman et al. (2003) have stated that “the existing literature does not provide strong support for the effectiveness of wraparound” (p. 138), while a review of children’s mental health interventions characterized the wraparound evidence base as being “on the weak side of ‘promising’” (Farmer et al. 2004; p. 869). Since these reviews were published, however, a number of steps have been taken to address the weaknesses in the evidence base. These steps are reviewed below.

Specification of Practice Model

First, as described above, better clarity has been achieved on the wraparound practice model as well as the organizational and system capacities necessary to optimally support implementation (Walker and Bruns 2006; Walker et al. 2003; Walker and Koroloff 2007). In turn, this clarification of the practice model has made possible the development—and subsequent validation—of fidelity measures that can be used both to inform local implementation and to interpret and to synthesize research findings (Bruns et al. 2004; 2008). These developments have allowed recent published research on wraparound to be more specific with respect to what was implemented (Bruns et al. 2006; Stambaugh et al. 2007), the National Institute of Mental Health has provided support for the first federally-funded study of the wraparound process (Walker et al. 2008), and the Child, Adolescent, and Family Branch of SAMHSA has provided support to a national initiative that supports wraparound dissemination.

Mechanisms of Change

Second, having an accepted definition of the wraparound model has also helped the field develop a clearer theory for describing the role that the wraparound process plays in service delivery and the impacts that can be expected when wraparound is implemented with fidelity. As indicated by its description, wraparound is not a treatment per se, but rather a method for enhancing the effectiveness of the services and supports that a child and family receives. As such, wraparound is one of a growing number of service enhancements that are being developed in children’s mental health. Other examples include family education and support services (see Hoagwood 2005, for a review) and family engagement strategies (e.g., McKay and Bannon 2004).

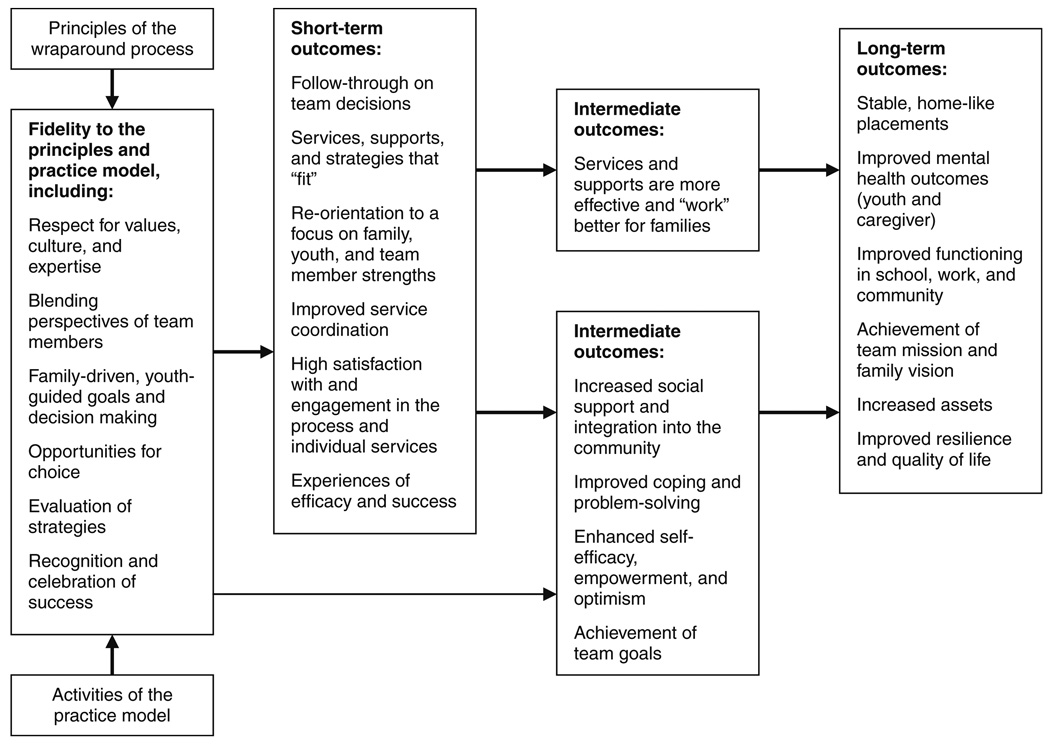

According to the theory proposed by Walker and Bruns (2008), a faithfully implemented wraparound process enhances treatment outcomes through two primary routes. First, as a collaborative process driven by youth and family perspectives, wraparound planning (1) results in services and supports that better fit the family’s needs and thus are perceived as more relevant, (2) develops strategies to overcome obstacles to follow through, and (3) consistently engages the young person and his or her family more fully in treatment and other decisions (see Fig. 1). The theory also proposes a second primary route to positive outcomes that is based more on the activities of process itself, rather than through enhancing treatments. Through this route, wraparound increases family and youth capacity to plan, cope, and problem solve. The experiences of making choices and of setting and reaching goals contribute to the development of self-efficacy, empowerment, and self-determination. There is robust research evidence that people who possess these attributes experience a variety of positive outcomes, including mental health and well being outcomes (see Walker 2008a, for a review of this research).

Fig. 1.

A theory of change for the wraparound process (from Walker 2008a, b)

Additionally, the holistic, team-based, and coordinated approach provides an opportunity for a more complete understanding of a youth’s development and social contexts, which typically are organized around multiple interrelated risks that render single-factor interventions to be ineffective (Farmer and Farmer 2001). Though these mechanisms of change have yet to be rigorously tested, elucidation of the basic research in support of this theory of change has helped clarify wraparound’s role in promoting positive outcomes as well as provided a major advance in the model’s research base.

Evidence from Controlled Studies

New research studies and new reviews of relevant wraparound research have emerged in just the past few years. A comprehensive review (Suter and Bruns 2008) found 36 outcome studies of wraparound, the majority of which were published in peer-review journals. Among these, seven controlled studies (four experimental and three quasi-experimental) were found in the peer-reviewed literature. In contrast to most interventions, controlled studies of wraparound have been conducted in a wide range of “real-world” settings and systems. For example, in addition to three studies conducted in the context of the children’s mental health systems (Bickman et al. 2003; Evans et al. 1996; Hyde et al. 1996), Carney and Buttell (2003) conducted a randomized study of wraparound implementation for 141 youth referred to court or adjudicated due to delinquent behavior. This study found that the wraparound group missed less school, was suspended less often, was less likely to run from home, was less assaultive, and less likely to be stopped by police; however, between-group differences in arrests and incarceration were not significant. Pullmann et al. (2006) conducted a quasi-experimental study comparing outcomes for 106 previously adjudicated youth enrolled in a wraparound program compared to a historical comparison group of 98 youth who did not receive the program. Results found lower recidivism and fewer days in detention for the wraparound youth and, for those who did serve in detention, fewer days and fewer stays in detention.

Two studies, one experimental (Clark et al. 1996) and one quasi-experimental (Bruns et al. 2006) have also been conducted in the child welfare system. The former study found that 54 youth enrolled in a wraparound-like program for foster youth with emotional and behavioral problems were significantly more likely to live in permanency-type setting following the program, had significantly fewer days on runaway, and fewer days incarcerated, compared to 77 youth in standard practice foster care. No group differences were found in several other outcomes, including rate of placement changes, days absent from school, and days suspended; and child behavioral outcomes were more positive only for boys (Clark et al. 1996). The latter study found small to medium effects in favor of the wraparound group compared to standard child welfare practice across a range of outcomes, including increased residential stability and decreased reliance on out of community placement, as well as improved behavioral, functioning, and school outcomes (Bruns et al. 2006).

The existence of seven published, controlled studies provided an opportunity for the first meta-analysis of published studies of the wraparound model (Suter and Bruns 2009). Results of the meta-analysis found that mean treatment effects across outcome domains ranged from medium for youth living situation (0.44) to small for mental health outcomes (0.31) and juvenile justice related outcomes (0.21). The overall mean effect size across studies and outcome domains was 0.33, which increased to .39 when excluding results for two studies for which direct calculation of effect sizes was not possible. Similar effect sizes (.30–.38) were found in a recent meta-analysis comparing established evidence-based treatments (EBTs) to usual clinical care for youth with mental health disorders (Weisz et al. 2006), an appropriate yardstick given that all seven studies in the wraparound meta-analysis compared wraparound to “services as usual” (as opposed to wait-list or no-treatment controls). At the same time, the number of studies included in this first meta-analysis of wraparound is small, and the studies themselves suffer from methodological problems. For example, several of the studies relied on matched comparison designs, raising concerns about group equivalence at baseline. Attrition was high or not reported in several studies, and only one study of the seven reported fidelity scores. In addition, because several of the studies were conducted before consensus was widely achieved on the components of the wraparound practice model, it is difficult to know which of the studies represent tests of the effects of a “true” wraparound process.

In sum, though interpretation of the evidence base for wraparound is complicated by the small number of studies and methodological shortcomings, results indicate that wraparound can potentially yield better outcomes for youth with serious emotional and behavioral problems when compared to youth receiving conventional services. The positive results found in this review of formal research studies are bolstered by additional findings from local and state evaluation studies pointing to significant shifts in the settings in which youth live as well as related costs (e.g., Kamradt et al. 2008; Rauso et al. 2009). Though not widely considered an “evidence-based treatment,” with syntheses of recent research, increasing definitional clarity, and development of fidelity measures, the wraparound model is moving toward being established as an “evidence-based process,” especially with respect to maintaining children and youth in their homes and communities. This is the outcome for which wraparound has historically been most typically applied; currently, it also seems to be the outcome for which there is the strongest evidence for impact.

Major Implementation and Policy Issues Facing Wraparound

As described above, multiple factors are currently pushing for increased deployment of care management using the wraparound process as an alternative to out-of-home or out-of-community placements and/or as a way to improve the quality of service planning for youth with complex needs. However, wraparound continues to provide conceptual and logistical challenges to the children’s behavioral health field. In the rest of this section, we will delineate just a few of these issues, before turning to recommendations for federal policy that can support effective local implementation.

Continued Definitional Confusion

Unlike many treatment models, wraparound was not initially developed by a single developer or research team, and the model is not proprietary. Even though now there is greater consensus as to what a model-adherent wraparound planning process consists of, the practice has a long tradition of being “grassroots,” and it continues to evolve. Even the model description and support materials produced by the National Wraparound Initiative are intended to allow flexibility in terms of adaptations to different populations of focus and how local teams achieve the principles in practice (Walker and Bruns 2006). Though this approach to model specification is intended to increase rigor while still ensuring local individualization, it has not fully addressed the longstanding uncertainty about what represents “true” wraparound.

More appropriate than standardization of the process, however, is the need to recognize and characterize wraparound’s various manifestations. With the recent increases in research and model specification, some jurisdictions have emphasized the practice aspects of wraparound and have focused on “high-fidelity” implementation of a full care management process at the youth- and team-level that includes the procedures described earlier in this paper. In other places, child-serving agencies and systems view wraparound as an overall “approach” to service planning and delivery for any population, and define the work primarily by the principles. Finally, for many, a “wraparound service” continues to be a specific, categorical service (rather than a care planning process), such as in-home behavioral support, or a term used to describe a range of different types of flexible supports (e.g., transportation, recreation) that may be available to a youth or family.

All the above issues make it difficult for providers, advocates, researchers, and policy-makers to communicate about the model, and complicate research and implementation efforts. The situation is made even more complex by the presence of models and frameworks that resemble wraparound, but are referred to by other names, such as family-group decision making, a child welfare model that employs a trained coordinator to convene the involved family and agency personnel to create a family-driven safety plan (Pennell and Burford 2000). In the near future, a more holistic and integrated framework that acknowledges but differentiates all these different “flavors” of wraparound and individualized care planning will likely be helpful, as will more research on which of the practice elements are most important for different types of youth and families in different situations.

The Fidelity Problem

Definitional confusion contributes to another frequently observed concern with wraparound, which is how to define, ensure, and measure fidelity. With the wraparound process only recently specified (and not proprietary) and fidelity measures a relatively new phenomenon, the field has struggled with the question of what represents model-adherent implementation. Research has shown connections between fidelity to the full care coordination process and outcomes, and associations between system factors and fidelity (see Bruns 2008, for a summary). However, research has shown that indicators of high-quality practice (at both the system and practice levels) are often lacking, even in initiatives that call themselves “wraparound” (Bruns 2008; Walker et al. 2003). In addition to continued research on what factors are most critical to achieving outcomes, the children’s services field will benefit from more consistent guidance about what represent the “non-negotiables” for deploying the wraparound model, as well as from incentives to conduct more consistent quality assurance and fidelity monitoring.

Workforce Development

A major component of the fidelity issue in wraparound clearly relates to workforce development. Without clear expectations for practice—combined with effective training, coaching, and supervision—the complexities of implementing the wraparound process can overwhelm and confound staff persons who are hired to fill key roles. Because there is no single recognized “purveyor organization” with which local systems must contract to receive training and technical assistance (as is the case with MST, FFT, and MTFC), each state and/or program is forced to scan the national landscape for potential trainers, and/or develop their own plan for human resource development. Though this may help local initiatives develop a more locally appropriate approach, it also may result in underdeveloped plans, poor staff training, and, consequently, poor implementation and outcomes.

To overcome such concerns, greater clarity is needed on how to put the wraparound principles into action on the ground level with teams and families. For example, what are the techniques, tools, and technologies that can help a wraparound facilitator translate strengths into components of a wraparound plan? What are the best methods for working with a diverse team to set goals and measure progress over time? With such clarity becoming better established, a more effective national infrastructure is now needed that can support wraparound programs to build effective human resource development plans, identify core skill sets, and provide expectations for how staff should be selected, trained, supervised, and possibly certified. At a broader level, it also would be helpful if professional training programs would more consistently build relevant instruction into their curricula. Such components could be applicable beyond wraparound or even behavioral health, such as facilitating collaboration, running an effective team meeting, focusing on strengths, and partnering with families and consumers.

Available Treatments and Supports

The system-level “blueprint” for wraparound implementation states that a community or initiative “should develop mechanisms for ensuring access to the services and supports that wraparound teams need to fully implement their plans” (Walker 2008b). However, as it becomes increasingly understood that the wraparound process represents an enhancement strategy (rather than a treatment), questions arise about what specific services and therapies should be consistently made available to wraparound programs and teams. Though it may be ideal to envision availability of a full continuum of evidence-based treatments (EBTs) as well as support services (such as in-home supports, respite care, mentoring, recreation, and so forth), studies of systems of care have found that it can be challenging to simultaneously attend to all these multiple strands of effort (e.g., system-building activities, high-fidelity wraparound care coordination, implementation of specific EBTs), straining the efforts of local systems of care (Johnson and Sukumar 2007). In other states and systems, wraparound may unfortunately be identified as a solution unto itself, without consideration of the specific services that should also be available to the population of focus.

Currently, there is emerging consensus that many wraparound initiatives will benefit from availability of certain services, such as parent-to-parent peer support, youth advocacy, clinicians who can respond flexibly to the needs of wraparound teams, and behavioral interventions that provide help to caregivers and/or schools (see related chapters on these topics in Bruns and Walker 2008). Ultimately, however, more research and better guidance is needed around what services and supports should be available in wraparound initiatives for different types of populations (e.g., transition age youth, young children, youth involved in child welfare or juvenile justice), and how best to integrate these services into a wraparound initiative to maximize both efficiency and alignment with the evidence base on effective practices.

Building the Research Base

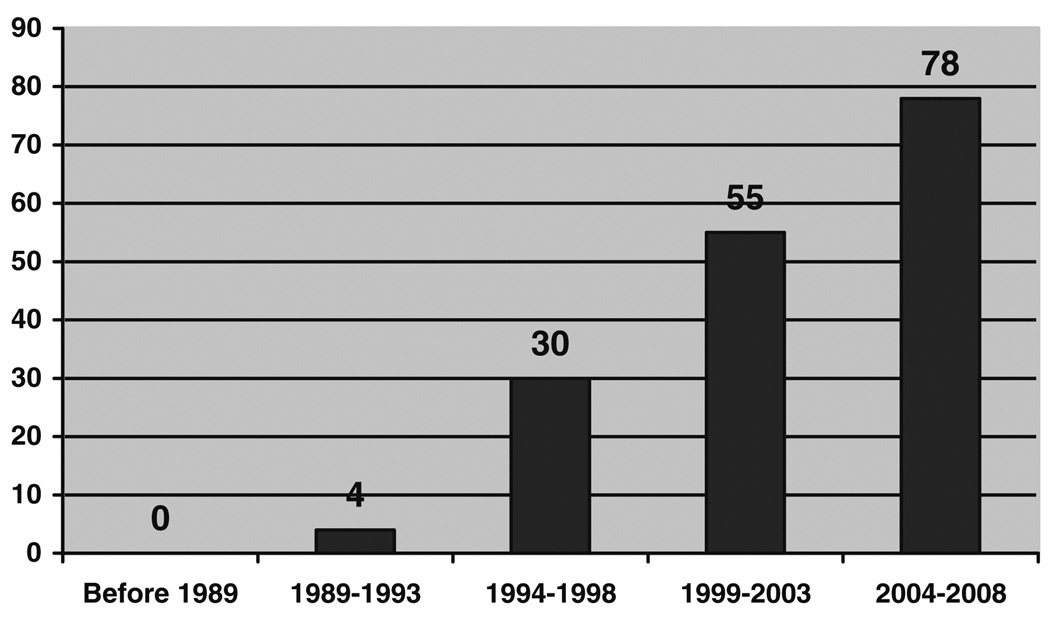

Many of the issues described in the preceding sections could be illuminated through an expansion of the research base on the wraparound process. Though there has been a linear increase in peer-reviewed research on the model in the last decade (See Fig. 2), as well as new federal investments in comparative effectiveness research, the wide range of applications of the wraparound process demands a significant increase in controlled outcomes studies across different populations of focus and types of implementation approaches. Equally important are studies of the context and process of implementing the various care coordination models. As discussed in the preceding sections, program developers and policy makers need to be able to make decisions based on research that can hold up to scrutiny. For example, what mechanisms account for the most variance in youth and family outcomes? What is the relative importance of different services (e.g., clinical treatments, support services), and/or specialized components for different populations (e.g., behavioral support in school-based wraparound or supported employment for transition-aged youth)?

Fig. 2.

Expansion of the research base on “wraparound:” Number of unduplicated studies found in Medline, Web of Science, and PsychInfo

In general, given the individualization that is possible at the community as well as youth and family level, multiple studies are needed on the effectiveness of different manifestations of the model. Synthesis of the research evidence will need to be done carefully, and include consideration of issues such as the population of focus, implementation fidelity, and organizational and system context.

Cost Effectiveness

In addition to better understanding of wraparound’s potential effectiveness, the children’s services field has a critical need for better data on the cost-effectiveness of the model and the factors that contribute to its being cost-effective. As described above, community-level evaluations in many jurisdictions have found that implementing intensive community-based services for youth who would otherwise be placed in costly out-of-home placements yield significant cost savings (or at least cost neutrality). At the same time, however, many wraparound initiatives have been undone by perceptions of costs that outstrip savings, or by the inability to document where cost offsets were being achieved.

There are certain factors that seem to contribute to cost-effectiveness of wraparound initiatives. Certainly, one is to restrict the populations of focus to youth for whom more costly out-of-community placement is expected or likely. Another is to rely on a care management entity that can blend funding from multiple systems and then serve as a central fiduciary agent, with the ability to negotiate case rates, assume risk, manage entry of youth to the program, and track outcomes and costs with clear expectations for what will be achieved. Such wraparound projects are often pointed to as the “purest” expression of wraparound, and may also have the greatest potential for cost-effectiveness and long-term sustainability. However, they are also the exception rather than the norm among wraparound projects nationally. In sites that do not use this model, better evidence is needed for the cost-effectiveness of using care coordinators, family partners, and other “add-ons” to existing services and structures.

Of course, the ability of a local system to implement wraparound cost-effectively is also highly dependent on federal funding policies and priorities. Strategic shifts in such policies could help tip the balance toward building more sustainable community-based initiatives (including wraparound programs) that support youth to live and thrive in their communities. We will now turn to this topic.

Recommendations for Federal Policy and Action

Despite the gaps that remain in our understanding, wraparound is based on a commonsensical proposition increasingly supported by evidence: That youth with complex needs who are involved in multiple systems will be more likely to experience positive outcomes and remain in their communities if they have a single, coordinated plan of care, along with necessary resources to support its implementation. In principle, the federal government shares this philosophy. SAMHSA, the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, the CMS Division of Advocacy & Special Initiatives, as well as other agencies have promoted approaches that encourage collaboration among agencies so that each child and family has a single plan of care. However, there is broad consensus that federal policies and programs present significant barriers to actual implementation of cross-system strategies such as the wraparound process. Many of these barriers are presented by the rules of federal programs for children themselves, but much of the problem is actually borne of the fragmentation that results from the proliferation of many different programs that address the particular needs of subpopulations of children (Koyanagi and Boudreaux 2003).

The recommendations that follow span a range of areas, but most focus on potential means for shaping federal policies, to allow them to be more supportive of intensive community-based programming, to make implementation more feasible and effective at the state and local level, and to support the wraparound principles in general.

Federal Policies and Programs that are Better Aligned and More Flexible

It is well acknowledged that rules associated with federal programs hamper efforts to develop responsive state and local systems for youth who are touched by more than one of these programs. As summarized by Koyanagi and Boudreaux (2003), these issues are the result of a political system that (1) targets certain children as worthy of a category of specific services, (2) places limits on the level and type of these services for which government is willing to pay, and (3) assigns responsibility for oversight of these services to agencies that function autonomously and with relatively little collaboration with one another. Three federal programs are of particular importance to the population of focus discussed in this paper—Medicaid, Title-IV-E child welfare services, and special education. All three programs potentially provide critical supports to children with complex behavioral health needs. Ideally, support to this extremely complex (and costly) population of youth would be provided by blending resources from these federal programs into a comprehensive array of coordinated services. However, eligibility rules do not align, meaning that individual children may be eligible for one program but not the other(s).

Full enumeration of problems posed by and solutions to the complexity and fragmentation of federal programs is beyond the scope of this paper. However, several high-level recommendations (most of which have been made repeatedly over the past 25 years) can be reinforced. At a very general level, the federal government needs to establish a mission for serving children with behavioral health problems that cuts across programs and systems and includes goals and indicators of success, because at the federal level, each agency has its own mission and there is little collaborative process (Koyanagi and Boudreaux 2003). Progress in this area could be initiated by establishing an office of children’s mental health policy. Such an office could be part of an executive-level office of national mental health policy located within the White House’s Office of Health Reform or within the Department of Health and Human Services [which includes the Administration for Children &Families (ACF), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), and SAMHSA].

Once established, a national office of children’s mental health policy could oversee the building of empowered collaborations across federal agencies that are charged with activities such as establishing common outcomes and indicators, reviewing coverage of mental heath care across federal programs, and making recommendations for closing gaps in coverage. Such an office could also oversee a process of remedying several particularly vexing problems with current federal programs, such as eligibility rules and assessment requirements. Currently, Medicaid, federal block grants, and special education have incompatible definitions of emotional and behavioral problems in children. More consistent terminology is needed across programs, so that children and youth who need mental health services can be a single, identifiable group with access to a range of local services and supports appropriate to their level and type of needs. This is particularly true of inconsistencies across the mental health and education systems, which currently create barriers to serving children with emotional and behavioral problems in schools.

In addition to inconsistency in terminology, such an office could address barriers to continuity of care for children and youth involved with multiple systems. For example, while Medicaid cannot be used for youth who are in a detention or commitment facility, there is no consistency across states on using Medicaid for youth who are pre-adjudicated or awaiting a community placement. Federal guidance on states’ ability to use Medicaid to support youth involved with juvenile justice would be helpful, and a true shift to a seamless continuum of care would begin with CMS supporting legislation to remove the exclusion of adjudicated, detained youth from Medicaid eligibility.

Greater collaboration at the federal level could also address the intensifying and rather bizarre phenomenon whereby various systems (e.g., mental health, early intervention, substance abuse, maternal and child health) have their own unique federal grants and rules to encourage development of collaborative, cross-system reform initiatives on behalf of youth with complex needs. Such grants and initiatives are well-intentioned and indeed often result in implementation of the wraparound process. However, the lack of federal coordination of these initiatives has ironically resulted in “system of care silos,” with rules that demand multiple and overlapping local and state coordinating entities, data and evaluation requirements, and even eligibility requirements. In keeping with the intent of these programs, localities and states need to be allowed to have consistent eligibility requirements, a single collaborative body, and cross-cutting data management and evaluation efforts across all these federal initiatives. Federal funds for developing management information systems (MIS) should be derived from a common source, or allowed to be blended locally, so that states and communities can create a single, cross-agency MIS. All of the above steps would help ensure that state and local wraparound initiatives are embedded in policy environments that are supportive of individualized, team-based service provision.

Funding that Supports the Principles and Implementation of Wraparound

Children and youth with serious and complex behavioral health needs that could benefit from wraparound care coordination are typically served through public mental health services, the primary funding source of which is Medicaid. However, there is broad consensus that policy decisions from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) as well as SAMHSA fail to support provision of wraparound or the evidence-based clinical practices to which wraparound teams must have access.

Federal policy should support provision of adequate resources to states to serve these children and youth. In particular, CMS should clarify to states that several key services and supports that are frequently accessed by wraparound teams are allowable under Medicaid. These include respite services; peer support services (family peer support and youth peer support); mental health consultation services (particularly to child care providers and schools, especially for the 0–5 population); mobile crisis and stabilization services; coverage for providers to participate in service/team planning meetings; coverage for provider-to-provider communication about a given child or youth receiving treatment (“collaborative care”); services for parents and siblings, even when they themselves are not Medicaid eligible or do not carry a mental health diagnosis; and treatment foster care, among others. CMS should do the following to improve access to these services: (1) clarify to states that these are allowable services; (2) provide examples of service descriptions and billing codes used by other state covering these services; and (3) designate, as necessary, new billing codes for certain services such as treatment foster care.

Programs other than Medicaid also need to have financing policies reviewed and remediated so they can be more in line with the goal of comprehensive, community-based services. For example, through Title IV-E child welfare funds, the federal government provides billions of dollars for services for children in out-of-home placements such as foster care, but many times less to maintain children and youth with their families (Cooper et al. 2008). This priority must be readjusted, such as by making Title IV-E dollars available to serve children still at home but at risk of out-of-home placement.

While individual programs’ policies are being attended to, the federal government should also find ways to support more effective use of these streams of revenue, such as by encouraging ways to combine funds into a single pool from which localities can pay for individualized wraparound service plans. Currently, some federal waiver programs allow for limited degrees of such “blended” or “braided” funding approaches, but states and localities often do not pursue such opportunities due to confusion about rules and application procedures. The federal government should pursue the use of bundled rates or case rates, not only for intensive care management approaches such as wraparound, but also for certain evidence-based approaches such as MST and MTFC, which do not lend themselves to 15-minute billing increments. CMS in particular should direct states that the use of bundled rates or case rates is allowable and should provide examples of how such rates are determined and monitored for effectiveness and cost savings. Case rates have the potential to provide tremendous individualization and flexibility while restricting costs.

Support for Training and Workforce Development

As part of a new commitment to funding evidence-based and coordinated care, administrative and fiscal policies must be aligned with strategies to support effective workforce development. For example, any new initiatives to expand provision of services for youth with complex mental health needs should include expectations for training those who will serve in key roles, such as wraparound care coordinators. Existing training funds—such as from Title IV-E, which is currently restricted to training for staff directly interacting with children in child welfare—should be more flexible in order to train a wide range of workers who serve in key capacities for families engaged in wraparound, including care coordinators and family support partners as well as partner agency staff who should be involved in the wraparound teams or plans of individual children and youth. At a broader level, Medicaid regulations should be more supportive of the enhanced training, coaching, and supervision expectations of evidence-based treatments that are required by wraparound teams. The greater federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) available for training of “medical” professionals should extend to individuals who are responsible for care coordination of children and youth with complex mental and behavioral health needs.

Finally, bold endeavors to train a national cohort of mental health workers are needed. Because much of the work of wraparound teams can be conducted by individuals who have not received formal clinical training, high-quality expansion of availability of models such as wraparound could be supported by providing tuition assistance or student loan forgiveness to a corps of providers who receive intensive training in the philosophy and relevant skills of the wraparound process, and who then are required to serve in this capacity for a certain number of years. There should be an exploration of an expansion of Graduate Medical Education funding in Medicaid to include other disciplines, such as social work. It is difficult to find necessary funds for clinical training to support best practices in child welfare or juvenile justice in particular. As some of these individuals gain additional training and ascend the career ladder, such a program would also help to address the chronic shortage of mental health workers in the system (Tolan and Dodge 2005).

Support Quality and Fidelity

As alluded to in the section above, existing and new federal programs and reimbursable services should demand high-fidelity implementation as well as fidelity monitoring both for EBTs and for enhancement strategies such as wraparound. Block grants and waiver programs that may foster development of wraparound-like programs should include specific language about how services must be delivered. While the requirement by CMS for all 1915(c) Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facilities (PRTF) Demonstration Grant Sites to implement the wraparound process with fidelity monitoring is a positive step, initial implementation in a small number of states suggests that a comprehensive understanding about wraparound was lacking prior to initiation of the demonstration waiver and that the required fidelity tools are not necessarily being used to support practice improvement. Since wraparound is not proprietary, many individuals and organizations lay claim to “providing wraparound” even as the core tenets of the model are not implemented. States and localities should be required to establish adequate workforce development and quality improvement procedures before implementing wraparound as the required practice model in federally funded projects.

Reduce Incentives for Out of Home Placements

As alluded to in the above sections, Medicaid rules (as well as those of other federal programs) are highly complex, to the point that mythologies abound about what is and is not permitted by federal rules. Regardless of the level of sophistication of state and local officials about the rules, it is often easier to obtain Medicaid reimbursement for a child’s out-of-home placement than to obtain federal resources to prevent such placements. The result is that wraparound and similar initiatives that may be quite effective at maintaining youth with very complex needs in the community, preventing custody relinquishment, and so forth, are viewed as overly costly because they require investment of state general fund dollars, as opposed to out-of-home placements for which the federal government will pick up a large portion of the tab. This situation persists despite a continued lack of evidence for the effectiveness of these types of out-of-home placement options (Burns et al. 1999; Curtis et al. 2001; Greenbaum et al. 1996), and clear goal statements across federal agencies to serve children and youth in the most normalized, home-like environments possible.

Readjusting these priorities will require federal attention across the different child-serving agencies to de-emphasize policies that encourage out-of-home placement, increase investment in early intervention and preventive community-based services, and develop federal programs (described above) that encourage states and localities to develop capacity to effectively serve children and youth in their communities. If results from the evaluation of the 1915(c) Demonstration Project provide evidence that home and community-based services for this intensive population of PRTF-eligible youth are both cost neutral and provide outcomes that are at least equivalent to those achieved in a PRTF for the same population of youth, it will be important for the Administration and Congress to make the PRTF Demonstration Project a permanent option for states under Section 1915(c) of the Social Security Act.

Research

Finally, the federal government should continue its recent movement back toward investing in research that can inform policy decisions in health and, more specifically, children’s behavioral health, including comparative effectiveness studies that can shed light on how we can best invest our limited resources on behalf of children with complex needs. President Obama recently pledged to increase the proportion of our gross domestic product (GDP) dedicated to research and development to 3%. This is a positive trend overall, but at the same time, it has been noted that the total percent of our research and development efforts spent on children’s programs (including education) and child development is only about 0.3% of GDP (Tolan and Dodge 2005), which translates to less than one-hundredth of one percent of our total GDP. This seems an embarrassingly small investment, and begins to explain why decisions around children’s prevention and mental health programming sometimes seem so uninformed and/or arbitrary, as well as why investments in children’s mental health interventions often have difficulty standing up to scrutiny during difficult financial times.

Given the substantial number of states and localities attempting to use the wraparound model to intervene in the lives of these youth and their families, the gaps in our understanding described previously require multiple studies (followed by careful synthesis) of different variations of the basic framework, mechanisms of change, and the populations that are best served for this model. Research is also needed on the specific services types and clinical interventions that should be made available in different types of implementation efforts, and how best to connect wraparound teams to these services. In addition, studies of how organizational, system, and funding contexts interact with attempts to implement wraparound are critical. Given the significant policy and funding changes that typically must occur to attempt a high-quality wraparound initiative, federal sources of support need to substantially increase investment in research on how changes in mental health policy impact coordination of care, fidelity of wraparound implementation, access to needed services, costs, and outcomes. Recent modest increases in funding for policy research (NIMH 2008) that occurs in real-world systems– and that can yield lessons about real world implementation—must continue, despite the lack of rigorous controls that accompany these studies.

Conclusion

This paper has focused on the wraparound process and its role within the array of behavioral health services and interventions for youth. A discussion of wraparound is, by its nature, complex and interwoven with broader issues of values, systems structures, financing, and access to services. To some extent, this captures both the appealing and vexing aspects of wraparound: On the one hand, the process aligns with the paradigm of the evidence-based practice movement by providing a set of concrete, empirically supported activities to undertake with specific children. But on the other hand, making the process as effective as possible requires significant macro systemic effort.

Though difficult to capture in a simple sound bite, this work nonetheless reflects principles espoused by both community psychology as well as the new administration—that progress will ultimately be based on both a rigorous examination of “what works” along with intentional effort to build on the assets of individuals and communities, foster collaboration among community members, and appreciate cultural diversity. We are hopeful that the current push for progress toward productive health care policies will also meaningfully shape the federal government’s approach to children’s behavioral health, including consideration of the recommendations enumerated in this article. We are also excited to join forces with community psychologists and other researchers who can combine skills in examining individual- and family-level change with systems in order to better understand the full potential of the wraparound process.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Child, Adolescent and Family Branch of the Center for Mental Health Services, US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and by the National Institute for Mental Health (R34 MH072759). We are grateful to Gary Blau, Alison Barkoff, Connie Conklin, and an anonymous reviewer for feedback on an earlier draft. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of the Center for Mental Health Services, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the National Institute for Mental Health or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

This can occur even in the context of families and youth who are involved in involuntary services, such as child welfare or juvenile services. Families and youth are still able to have a voice in the planning process, and that voice is heard and respected.

Contributor Information

Eric J. Bruns, Email: ebruns@u.washington.edu, Division of Public Behavioral Health and Justice Policy, University of Washington School of Medicine, 2815 Eastlake Ave E, Suite 200, Seattle, WA 98102, USA.

Janet S. Walker, Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA

Michelle Zabel, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Marlene Matarese, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Kimberly Estep, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Deborah Harburger, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Madge Mosby, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Sheila A. Pires, Human Service Collaborative, Washington, DC, USA

References

- Alexander JF, Sexton TL. Functional family therapy: A model for treating high-risk, acting-out youth. In: Kaslow FW, editor. Comprehensive handbook of psychotherapy: Integrative/ eclectic. Vol. 4. New York: Wiley; 2002. pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JA, Wright ER, Kooreman HE, Mohr WK, Russell L. The Dawn Project: A model for responding to the needs of young people with emotional and behavioral disabilities and their families. Community Mental Health Journal. 2003;39:63–74. doi: 10.1023/a:1021225907821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L, Smith CM, Lambert EW, Andrade AR. Evaluation of a congressionally mandated wraparound demonstration. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2003;12:135–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns EJ. The evidence base and wraparound. In: Bruns EJ, Walker JS, editors. The resource guide to wraparound. Portland, OR: National Wraparound Initiative, Research and Training Center for Family Support and Children’s Mental Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns EJ, Walker JS. The Resource Guide to Wraparound. Portland, OR: National Wraparound Initiative, Research and Training Center for Family Support and Children’s Mental Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns EJ, Burchard JD, Suter JC, Leverentz-Brady K, Force MM. Assessing fidelity to a community-based treatment for youth: The Wraparound Fidelity Index. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2004;12(2):79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns EJ, Rast J, Walker JS, Bosworth J, Peterson C. Spreadsheets, service providers, and the statehouse: Using data and the wraparound process to reform systems for children and families. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2006a;38:201–212. doi: 10.1007/s10464-006-9074-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns EJ, Suter JC, Leverentz-Brady KM. Relations between program and system variables and fidelity to the wraparound process for children and families. Psychiatric Services. 2006b;57(11):1586–1593. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.11.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns EJ, Leverentz-Brady KM, Suter JC. Is it wraparound yet? Setting quality standards for implementation of the wraparound process. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2008a;35(3):240–252. doi: 10.1007/s11414-008-9109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns EJ, Sather A, Stambaugh L. National trends in implementing wraparound: Results from the state wraparound survey, 2007. In: Bruns EJ, Walker JS, editors. The resource guide to wraparound. Portland, OR: National Wraparound Initiative, Research and Training Center for Family Support and Children’s Mental Health; 2008b. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns EJ, Walker JS National Wraparound Initiative Advisory Group. The resource guide to wraparound. Portland, OR: National Wraparound Initiative, Research and Training Center for Family Support and Children’s Mental Health; 2008c. Ten principles of the wraparound process. [Google Scholar]