Abstract

Background

The cognitive factor of Anxiety Sensitivity (AS; the fear of anxiety and related bodily sensations), is theorized to play a role in cannabis use and its disorders. Lower-order facets of AS (physical concerns, mental incapacitation concerns, social concerns) may be differentially related to cannabis use behavior. However, little is known about the impact of AS facets on the immediate antecedents of cannabis use.

Methods

The present study used ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to prospectively examine the relations between specific facets of AS, cannabis craving, state anxiety, and cannabis use in the natural environment using real-world data about ad-lib cannabis use episodes. Participants were 49 current cannabis users (38.8% female).

Results

AS-mental incapacitation fears were related to significantly greater severity of cannabis-related problems at baseline. During the EMA period, AS-mental incapacitation and AS-social concerns significantly interacted with cannabis craving to prospectively predict subsequent cannabis use. Specifically, individuals with higher craving and either higher AS-mental incapacitation or AS-social concerns were the most likely to subsequently use cannabis. In contrast to prediction, no AS facet significantly moderated the relationship between state anxiety and cannabis use.

Conclusions

These findings suggest facets of AS (mental incapacitation and social fears) interact with cannabis craving to predict cannabis use. Findings also suggest differential relations between facets of anxiety sensitivity and cannabis-related behaviors.

Keywords: anxiety sensitivity, anxiety, marijuana, cannabis, ecological momentary assessment

Introduction

Approximately six percent of the U.S. population endorse past-month cannabis use [1]. Strikingly, nearly one-third of current cannabis users exhibit cannabis-related problems significant enough to warrant a diagnosis of cannabis use disorder (CUD) [2]. Rates of CUD have risen over the past decade [2] and their prevalence nearly equals that of all other illicit substance use disorders combined [1]. Cannabis users with cannabis dependence are more than twice as likely to experience anxiety disorders than users without cannabis dependence [3]. Given the high rates of anxiety disorders among those with CUD, it may be that cognitive vulnerability factors characteristic of anxiety disorders may play important roles in certain aspects of cannabis use and its disorders.

Anxiety Sensitivity (AS; fear of anxiety and aversive internal sensations) has been conceptualized as a malleable cognitive vulnerability factor [4]. Although not all individuals with elevated AS experience anxiety disorders (and not all individuals with anxiety disorders experience elevated AS) [5], AS is elevated in anxiety conditions such as panic psychopathology and social anxiety disorder and prospectively predicts the future development of these problems [6]. AS may also play a role in cannabis use behaviors. Extant work on AS has found AS to be positively correlated with using cannabis to cope with negative affect [7] and severity of retrospectively reported cannabis withdrawal symptoms [8]. Also, individuals with cannabis dependence report greater AS than cannabis users without dependence [9].

AS maintains a higher-order construct structure: a global factor and three lower-order facets: physical concerns, mental incapacitation concerns, and social concerns [10]. People with elevated AS-physical concerns fear physical sensations (e.g., trembling, rapid heartbeat), whereas those with AS-mental incapacitation concerns fear losing control of their mind or “going crazy”. AS-social concerns are fears regarding others’ abilities to perceive observable physical sensations (e.g., stomach growling, appearing nervous). Although extant research on the AS-cannabis use relationship is promising, little empirical work has examined the specific role of lower-order facets on cannabis use behaviors.

Theoretically, it follows that particular lower-order AS factors may be especially related to cannabis use behaviors. For example, AS-physical concerns may act synergistically with state anxiety to predict cannabis use if a person with higher AS-physical concerns misinterprets anxiety-related physical sensations as dangerous and uses cannabis to manage these sensations, given relaxation is one of the most common reasons for cannabis use [11]. ASsocial concerns may interact with state anxiety to predict use if the person uses cannabis to attempt to manage potentially embarrassing physical symptoms of state anxiety (e.g., sweating, blushing). In fact, individuals with elevated social concerns reported greater desire to use cannabis during periods of elevated state anxiety than those with lower social concerns [12].

On the other hand, AS-mental incapacitation concerns could impact the relationship between cannabis craving and use. Craving can include obsessive thoughts about the desired substance as well as compulsive urges to engage in substance use [13]. Thus, someone with higher AS-mental incapacitation concerns may misinterpret cognitive symptoms of cannabis craving (e.g., obsessive thoughts) as a sign of ”going crazy” and may use cannabis to avoid these thoughts. In fact, AS-mental incapacitation, but not physical or social concerns, was related to reporting more severe cannabis withdrawal [8]. Yet it is not clear whether AS-mental incapacitation was related to more severe withdrawal symptoms or to rating withdrawal symptoms as more severe. Thus, one interpretation is that mental incapacitation concerns may be related to lower tolerance for cognitive symptoms of craving experienced during cannabis abstinence among cannabis users.

The incorporation of ecological momentary assessment (EMA) into prospective designs is one way to further elucidate the role of AS in cannabis use. EMA involves the use of daily monitoring of target behaviors. Some of the key benefits of EMA include: (1) collection of data in real-world environments, thereby enhancing ecological validity; (2) minimization of retrospective recall bias by assessing relations between affective states and behaviors while participants experience the affect and/or engage in the targeted behavior; and (3) aggregation of observations over multiple assessments to facilitate within-subject assessments of behaviors across time and context [14].

There is only one known published EMA study on the relationships between state anxiety and cannabis use [15]. In this study, state anxiety was unrelated to cannabis use. Yet, it may be that only those individuals with specific cognitive vulnerability factors (such as AS) are using cannabis in response to state anxiety. Further, these findings are limited in that: (1) the sample was predominantly female so little is known about the relations between anxiety and use in mixed-gender samples (important given men remain more likely to use cannabis [16]); (2) nearly half (48.1%) the sample denied cannabis use in the month prior to participation (and means of use during the monitoring period per participant were not reported making it difficult to ascertain whether these non-current users used cannabis during the monitoring period); and (3) they relied solely on responses to random prompts rather than also assessing the relationship between state anxiety and cannabis use during event contingent assessments such as when participants were about to use cannabis.

The aim of the present study was to use EMA to explore AS and its facets in relation to proximal antecedents of cannabis use. Specifically, we tested whether AS global scores as well as AS lower-order factors moderated the relationships of state anxiety and cannabis craving with cannabis use using real-world data about ad-lib cannabis use episodes during a two-week EMA monitoring period. It was expected that AS-physical and AS-social concerns would moderate the relation between state anxiety and use whereas AS-mental incapacitation concerns would moderate the relation between craving and use.

Method

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were recruited based on responses to a mass screening administered in undergraduate psychology classes at Florida State University from September 2006 to January 2008. Of the 3,200 undergraduates screened, 44.1% endorsed current cannabis use and were invited via email to participate. A total of 60 prospective participants came to the laboratory and were assessed for eligibility; yet, 3 were excluded because they denied lifetime cannabis use during the appointment and 3 were excluded due to non-availability of PDAs at the time of their appointment (see Figure 1). Thus, 54 participants were enrolled in the study but 1 was excluded for losing his PDA and 4 were not compliant with EMA protocol (information regarding compliance provided below).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study participants.

The final sample was comprised of 49 (38.8% female) participants aged 18–22 years (M=19.14, SD = 1.02). Despite inclusion criteria only requiring past three month cannabis use, participants in the present study reported heavy use relative to other undergraduate cannabis-using samples [17]. Specifically, they reported using cannabis an average of 5–6 times a week in the past three months with 40.1% reporting daily cannabis use and only 12.2% reporting less than weekly use. Regarding prevalence of current CUD, 26.5% met DSM-IV criteria for cannabis abuse and 36.7% met criteria for cannabis dependence. Although only 10.2% endorsed a history of anxiety treatment, 24% met DSM-IV criteria for a primary anxiety disorder. The racial/ethnic composition of the sample was: 2.0% American Indian, 83.7% Caucasian, 2.0% Hispanic/Latino, 10.2% mixed, and 2.0% other.

EMA Assessments

EMA data were collected via PDAs that were manufactured by Palm® (Z22 Handheld). Data were collected using forms created with Satellite Forms 5.2 developed by Pumatech. EMA data collection included three types of EMA assessments [18]. First, participants completed signal contingent assessments in which they completed assessments upon receipt of PDA signal. Participants were signaled six semi-random times throughout the day. The time of the signal was determined randomly to be within 17 min of each of six anchor times distributed evenly throughout the day (between 10:00 a.m. and midnight). Second, participants completed interval contingent assessments in which they completed assessments at the end of day (i.e., bedtime). Third, participants completed event contingent assessments in which they completed assessments each time they were about to use cannabis. Participants were presented with the same questions regardless of assessment type. Assessments were automatically date and time stamped.

Craving

Participants were asked: “Please indicate how much you are craving cannabis by tapping the number which best corresponds to your urge to use cannabis RIGHT NOW.” The item was rated on an 11-point scale from 0 (No Urge) to 10 (Extreme Urge). Similar scales have been used in prior studies of cannabis craving and been found to respond similarly to longer self-report craving scales [19–20].

State Anxiety

State anxiety was assessed using a Subjective Units of Distress (SUDs) [21] in which participants were asked to “Please indicate your current level of anxiety by circling the number that best corresponds with the way you are feeling RIGHT NOW” on an 11-point scale from 0 (Totally relaxed, on the verge of sleep) to 10 (The highest anxiety you have ever experienced). Similar SUDs ratings have been used in prior studies [20; 22].

Self Cannabis Use

Participants were asked to indicate if they were about to use cannabis (yes or no).

Procedure

Participants met individually with a trained clinical interviewer who obtained informed consent and administered a battery of self-report measures including the Anxiety Sensitivity Index which uses a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = “very little” to 4 = “very much”) to assess the degree to which participants were concerned about possible negative consequences of anxiety symptoms (e.g. “It scares me when I feel shaky”) [23]. This measure has been shown to be unique from, and demonstrate incremental validity to, trait anxiety [24]. In the present sample, the 16-item ASI-global (α = .90), the 8-item ASI-physical (α = .88), and the 4-item AS-mental (α = .88) scores demonstrated adequate reliability with the 4-item AS-social scale (α = .62) demonstrating somewhat questionable reliability. Cannabis-related problems were assessed with the Marijuana Problems Scale (MPS) [25], a 19-item list of negative social, occupational, physical, and personal consequences associated with past 90 day cannabis use. Problems were rated on a 0–2 scale (0=no problem, 1=minor problem, 2=serious problem). This measure has demonstrated good reliability in prior work [26–28] and in the present sample (α = .85).

Participants were trained on the use of the PDA. The three types of assessments were explained and participants were instructed not to complete assessments when it was inconvenient (e.g., while in class) or unsafe (e.g., while driving). In these instances, they were asked to respond to any PDA signals within one hour if possible. Participants were also given a handout that included the date for their second appointment (described below) and printed instructions of how to use the PDA for their reference during the monitoring period.

During the 14-day monitoring period, participants were sent daily e-mails reminding them to complete the day’s assessments (including a reminder of all three assessment types). Participants’ second appointment occurred two weeks after their initial appointment to return the PDA. During the second appointment, they were debriefed, given research credit, and provided local cannabis treatment referrals.

Statistical Analysis

Relationships between continuous baseline variables (AS global score, AS facets, cannabis problems) were examined using bivariate correlations. Bivariate correlations were also conducted to examine the relations between AS facets and cannabis use frequency during the monitoring period. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) models were conducted to examine whether frequent cannabis users differed from less frequent users on AS at baseline.

Hypotheses were evaluated using a series of mixed-effects models with binary logistic response functions. All models included a random effect for subject and fixed effects for other predictors. Independent variables were centered by subtracting the grand mean from each individual score. The cross-sectional relations between AS (global score and AS facets), cannabis craving, and cannabis use were examined by testing whether AS scores interacted with craving at a momentary level (i.e., whether AS scores interacted with craving at each assessment point to predict use at that assessment point). The temporal relations between study variables were examined by testing whether AS facets interacted with craving or state anxiety at one assessment point to predict cannabis use at the subsequent assessment. Specifically, AS facets × cannabis craving at one assessment point was used to predict cannabis use at the next assessment; and AS facets × state anxiety at one assessment point was used to predict cannabis use at the next assessment. Separate analyses were conducted for each AS facet. Pseudo R-squared values were calculated using error terms from the unrestricted and restricted models as described by Kreft and de Leeuw [29]. All analyses were conducted using PASW (formerly SPSS) version 18.0.

Results

Compliance with the EMA protocol was assessed by determining mean daily percentage of random prompts, mean daily percentage of end of day assessments, and mean percentage of random and end of day assessments completed per participant. Consistent with other EMA studies of substance use in non-treatment samples [30], participants completed a mean of 61% (SD=26%; range=2%–96% per participant) of random beeps, 64% (SD=19%; range=21%–93% per participant) of end of day assessments, and 62% (SD=23%; range=11%–.94% per participant) of both random and end of day assessments. Also in line with prior work [30], we retained data from participants with at least 20% compliance rates. Specifically, ratings from participants with less than 20% overall compliance rates (random + end of day assessments completed) were excluded. Although GLM does allow for missing data, it did not seem prudent to include days where half or more of the ratings were missing. Four participants were excluded from data analyses (see Figure 1). The remaining 49 participants completed 4,069 signal contingent assessments (M=83.19, SD= 3.33 per participant), 518 interval contingent assessments (M=10.73, SD= 3.50 per participant), and 452 event contingent assessments (M=10.75, SD= 10.05 per participant). Participants recorded a total of 732 cannabis use entries (M=16.26, SD= 15.08 per participant), recorded using all three assessment types. Participants reported an average of 1.33 (SD=1.63) cannabis use episodes per day. Signal contingent assessments were completed on average 14.8 (SD=62.5) minutes after the signal occurred. Cannabis craving ratings by date per participant ranged from 0–10 (M = 3.19,SD = 2.22) and state anxiety ratings by date per participant ranged from 0–8.5 (M = 2.15,SD = 1.49).

Correlations between AS scales and baseline reports of cannabis-related problems appear in Table 1. Only AS-mental incapacitation concerns were related to greater severity of cannabis-related problems. The size of this effect was medium [31].

Table 1.

Correlations between facets of anxiety sensitivity, cannabis use frequency, and severity of cannabis-related problems.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M (SD) | Range | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | AS-global scores | 15.41 (10.00) | 0–57 | |||||

| 2. | AS-physical concerns | .93** | 7.76 (6.34) | 0–32 | ||||

| 3. | AS-mental incapacitation concerns | .82** | .67** | 1.84 (2.51) | 0–14 | |||

| 4. | AS-social concerns | .71** | .46** | .53** | 5.82 (2.82) | 0–12 | ||

| 5. | Cannabis problem severity | .23 | .19 | .30* | .12 | 4.88 (4.59) | 0–27 |

p < .05,

p < .008.

At baseline, daily and non-daily marijuana users did not differ on AS measures: AS-global (F(1, 48) = .53, p = .470), AS-physical (F(1, 48) = .17, p = .681), AS-mental incapacitation (F(1, 48) = .01, p = .933), and AS-social (F(1, 48) = 2.58, p = .115). Cannabis use frequency during the monitoring period was also unrelated to AS-physical (r = −.14, p = .442), AS-mental incapacitation (r = −.10, p = .490), and AS-social (r = −.22, p = .147).

Anxiety Sensitivity X Cannabis Craving in the Prediction of Cannabis Use

Cross-sectionally, only the AS-social concerns × craving interaction was significant, β = 0.03, SE = .006, p < .001, pseudo R2 = .450 (Figure 2). Effect size estimates suggest that the main effects accounted for 43.4% of the variance in cross-sectional cannabis use (pseudo R2 = .434) with the interaction accounting for an additional 1.4%. Inspection of the graph suggests that individuals with higher craving and higher social fears were the most likely to use cannabis.

Figure 2.

AS-social concerns moderate the relationship between cannabis craving and cannabis use at the momentary level.

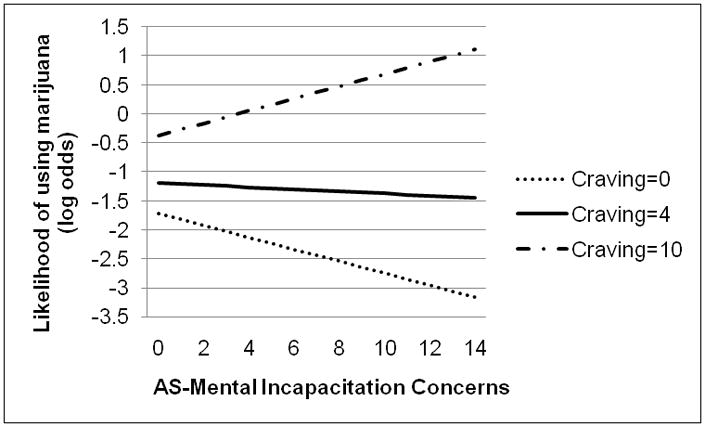

Prospective relations were next examined. Using Bonferroni corrections (p < .05/4 = .017), the following interactions were significant: AS-mental incapacitation concerns × craving, β = 0.02, SE = .01, p = .012, pseudo R2 = .236 (Figure 3) and AS-social concerns × craving, β = 0.02, SE = .01, p < .001, pseudo R2 = .182 (Figure 4). Effect size estimates suggest that the AS-mental incapacitation concerns × craving interaction accounted for an additional 1.4% of the variance in subsequent cannabis use (main effects pseudo R2 = .222) and the AS-social concerns × craving interaction accounted for an additional 2.4% of the variance (main effects pseudo R2 = .159). Inspection of the graphs suggests that individuals with higher craving and either higher mental incapacitation or social fears were the most likely to subsequently use cannabis.

Figure 3.

AS-mental incapacitation concerns moderate the relationship between cannabis craving at one assessment point and cannabis use at the subsequent assessment point.

Figure 4.

AS-social concerns moderate the relationship between cannabis craving at one assessment point and cannabis use at the subsequent assessment point.

Anxiety Sensitivity X State Anxiety in the Prediction of Cannabis Use

AS-global scores and AS facets did not significantly interact with state anxiety to predict cannabis use cross-sectionally (p’s > .20). Using Bonferroni corrections (p < .05/4 = .013), no interactions were significantly related to subsequent cannabis use. There was a trend for the AS-physical concerns × state anxiety interaction to be significant, β = −0.01, SE = .00, p = .018, pseudo R2 = .014. However, this interaction only accounted for an additional 0.8% of the variance in subsequent cannabis use and the variance attributable to main effects was also quite small (pseudo R2 = .005).

Discussion

AS-mental incapacitation concerns (but not AS-physical or social concerns) were significantly correlated with severity of cannabis-related problems, suggesting facets of AS may be differentially related to cannabis-related problems. This finding is consistent with an earlier investigation that found AS-mental incapacitation concerns were uniquely related to cannabis withdrawal symptoms [8]. It is possible that fears of negative consequences of mental incapacitation may lead to more problematic cannabis use as a method for coping with aversive thoughts related to cognitive dyscontrol. AS-global scores have been found to be related to using cannabis as a coping strategy [32].

The relationship between cannabis craving and use was moderated by AS-mental incapacitation and social concerns. Specifically, at lower levels of craving, individuals with higher AS-mental incapacitation and social concerns appeared less likely to use cannabis. However, individuals with higher craving and higher AS-mental incapacitation and social concerns were most likely to subsequently use cannabis. Notably, these significant moderational effects were above and beyond the large degree of variance accounted for by the main effects of craving and each AS facet. Given that our sample was comprised of relatively heavy cannabis users, these moderational analyses, despite accounting for small degree of incremental variance, could be clinically meaningful [33].

The impact of social concerns is particularly interesting as it moderated the relations between craving and use cross-sectionally (suggesting an impact at a proximal level) and was a prospective predictor of subsequent use. This finding is consistent with accumulating evidence that cannabis users with elevated social anxiety (a condition characterized by fear of social evaluation) tend to experience more cannabis-related impairment, including cannabis dependence [3; 28; 34–37]. Our findings suggest people who fear being evaluated by others may use cannabis to manage potentially observable symptoms of cannabis craving. Future work assessing momentary motives for using cannabis during cannabis use episodes will be an important next step.

Unexpectedly, no AS scale moderated the relationship between state anxiety and cannabis use. This finding seems counter to prior work in which AS-global scores were related to using cannabis to cope with negative affect [7]. Perhaps individuals with higher AS overestimate their reliance on cannabis to help regulate anxiety when in fact they are no more likely to use cannabis to manage anxiety than people with lower AS. Alternatively, when experiencing heightened state anxiety, those with higher AS may not be more likely to use cannabis if they fear use would be anxiolytic. This explanation is consistent with other work finding no significant relationship between the AS-global and coping motives for cannabis use [34].

The present results highlight the potential importance of particular aspects of AS in regard to cannabis use behaviors. Given AS is a malleable cognitive factor that can be targeted in intervention work [38], it may be prudent for future research to explore how changing specific AS facets (e.g., AS-social concerns) affects cannabis use behaviors.

Results should be considered in light of limitations. First, we emailed participants daily to remind them to complete the assessments and this strategy resulted in compliance rates that were somewhat higher than those reported in other EMA studies of non-treatment samples of substance users which, although obtaining comparable compliance estimates, assessed compliance only on days the recording device was used by the participant [30]. However, our participants were not given a “practice period”, a protocol common in EMA research [39–40]. Second, the present study examined undergraduate students. On the one hand, our data are thereby generalizable to groups particularly vulnerable to cannabis-related impairment (i.e., young adults, college students) [1; 41]. To illustrate, age of CUD onset peaks in late adolescence/early adulthood followed by a sharp decline [42]. Cannabis use prevalence rates from 2005–2007 were similar between college students and non-college peers [43] and over one-third of college cannabis users exhibit CUD symptoms [41]. Yet, future study is needed to examine whether the observed relations generalize to other populations. Third, we examined non-treatment seeking individuals to examine factors that maintain cannabis use uninfluenced by treatment. An important next step will be to identify factors that maintain cannabis use/increase lapse vulnerability among those attempting cannabis cessation. Fourth, we did not assess cannabis use motives or expectancies and future research could benefit from assessment of these important and relevant constructs. Fifth, we did not confirm that reported cannabis use actually occurred and future work incorporating biological verification of use is necessary. Sixth, future prospective and/or experimental work is necessary to determine whether experiencing higher AS-social and/or AS-mental incapacitation concerns makes one vulnerable to using cannabis in response to craving or whether using cannabis in response to cravings leads to increases in AS-social and/or mental incapacitation concerns.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a NationalInstitute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant F31 DA021457 awarded to Julia D. Buckner.

Contributor Information

Julia D. Buckner, Louisiana State University.

Michael J. Zvolensky, University of Vermont

Jasper A. J. Smits, Southern Methodist University

Peter J. Norton, University of Houston

Ross D. Crosby, University of North Dakota School of Medicine & Health Sciences and the Neuropsychiatric Research Institute

Stephen A. Wonderlich, University of North Dakota School of Medicine & Health Sciences and the Neuropsychiatric Research Institute

Norman B. Schmidt, Florida State University

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, et al. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agosti V, Nunes E, Levin F. Rates of psychiatric comorbidity among U.S. residents with lifetime cannabis dependence. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:643–652. doi: 10.1081/ada-120015873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity and panic disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:938–946. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor S, Koch WJ, McNally RJ. How does anxiety sensitivity vary across the anxiety disorders? Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1992;6:249–259. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ, Maner JK. Anxiety sensitivity: Prospective prediction of panic attacks and Axis I pathology. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zvolensky MJ, Marshall EC, Johnson K, et al. Relations between anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and fear reactivity to bodily sensations to coping and conformity marijuana use motives among young adult marijuana users. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:31–42. doi: 10.1037/a0014961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Marshall EC, Bernstein A. Incremental validity of anxiety sensitivity in relation to marijuana withdrawal symptoms. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1843–1851. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson K, Mullin JL, Marshall EC, et al. Exploring the mediational role of coping motives for marijuana use in terms of the relation between anxiety sensitivity and marijuana dependence. American Journal on Addictions. 2010;19:277–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zinbarg RE, Barlow DH, Brown TA. Hierarchical structure and general factor saturation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index: Evidence and implications. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:277–284. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reilly D, Didcott P, Swift W, Hall W. Long-term cannabis use: Characteristics of users in an Australian rural area. Addiction. 1998;93:837–846. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9368375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buckner JD, Silgado J, Schmidt NB. Marijuana craving during a public speaking challenge: Understanding marijuana use vulnerability among women and those with social anxiety disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2011;42:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anton RF. Obsessive-compulsive aspects of craving: Development of the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale. Addiction. 2000;95:S211–S217. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tournier M, Sorbara F, Gindre C, et al. Cannabis use and anxiety in daily life: A naturalistic investigation in a non-clinical population. Psychiatry Research. 2003;118:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434, NSDUH Series H-36) Rockville, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilmer JR, Walker DD, Lee CM, et al. Misperceptions of college student marijuana use: Implications for prevention. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:277–281. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wheeler L, Reis HT. Self-recording of everyday life events: Origins, types, and uses. Journal of Personality. 1991;59:339–354. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray KM, LaRowe SD, Upadhyaya HP. Cue reactivity in young marijuana smokers: A preliminary investigation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:582–586. doi: 10.1037/a0012985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buckner JD, Silgado J, Schmidt NB. Marijuana craving during a public speaking challenge: Understanding marijuana use vulnerability among women and those with social anxiety disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.07.005. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolpe J. Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science. 1968;3:234–240. doi: 10.1007/BF03000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kocovski NL, Rector NA. Post-event processing in social anxiety disorder: Idiosyncratic priming in the course of CBT. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32:23–36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the predictions of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rapee RM, Medoro L. Fear of physical sensations and trait anxiety as mediators of the response to hyperventilation in nonclinical subjects. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:693–699. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.4.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Curtin L. Comparison of extended versus brief treatments for marijuana use. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:898–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Fearer SA, et al. The Marijuana Check-up: Reaching users who are ambivalent about change. Addiction. 2004;99:1323–1332. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buckner JD, Keough ME, Schmidt NB. Problematic alcohol and cannabis use among young adults: The roles of depression and discomfort and distress tolerance. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1957–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buckner JD, Schmidt NB. Marijuana effect expectancies: Relations to social anxiety and marijuana use problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1477–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreft I, de Leeuw J. Introducing Multilevel Modeling. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hopper JW, Su Z, Looby AR, et al. Incidence and patterns of polydrug use and craving for ecstasy in regular ecstasy users: an ecological momentary assessment study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;85:221–235. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Marijuana use motives: Concurrent relations to frequency of past 30-day use and anxiety sensitivity among young adult marijuana smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abelson RP. A variance explanation paradox: When a little is a lot. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;97:129–133. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buckner JD, Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. Marijuana use motives and social anxiety among marijuana-using young adults. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2238–2252. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buckner JD, Schmidt NB. Social anxiety disorder and marijuana use problems: The mediating role of marijuana effect expectancies. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:864–870. doi: 10.1002/da.20567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Bobadilla L, Taylor J. Social anxiety and problematic cannabis use: Evaluating the moderating role of stress reactivity and perceived coping. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1007–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Lang AR, et al. Specificity of social anxiety disorder as a risk factor for alcohol and cannabis dependence. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42:230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt NB, Eggleston AM, Woolaway-Bickel K, et al. Anxiety Sensitivity Amelioration Training (ASAT): A longitudinal primary prevention program targeting cognitive vulnerability. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21:302–319. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, et al. Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:629–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH, et al. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:531–545. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caldeira KM, Arria AM, O’Grady KE, et al. The occurrence of cannabis use disorders and other cannabis-related problems among first-year college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:397–411. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stinson FS, Ruan WJ, Pickering R, Grant BF. Cannabis use disorders in the USA: Prevalence, correlates and co-morbidity. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1447–1460. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use 1975–2007 Volume II: College Students & Adults Ages 19–45. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2007. [Google Scholar]