Abstract

Background

A sit to stand task following a hip fracture may be achieved through compensations (e.g. bilateral arms and uninvolved lower extremity), not restoration of movement strategies of the involved lower extremity. The primary purpose was to compare upper and lower extremity movement strategies using the vertical ground reaction force during a sit to stand task in participants recovering from a hip fracture to control participants. The secondary purpose was to evaluate the correlation between vertical ground reaction force variables and validated functional measures.

Methods

Twenty eight community dwelling older adults, 14 who had a hip fracture and 14 control participants completed the Sit to Stand task on an instrumented chair designed to measure vertical ground reaction force, performance based tests (Timed up and go, Berg Balance Scale and gait speed) and a self report Lower Extremity Measure. A MANOVA was used to compare functional scales and vertical ground reaction force variables between groups. Bivariate correlations were assessed using Pearson Product Moment correlations.

Findings

The vertical ground reaction force variables showed significantly higher bilateral arm force, higher uninvolved side peak force and asymmetry between the involved and uninvolved sides for the participants recovering from a hip fracture (Wilks’ Lambda = 3.16, p = 0.019). Significant correlations existed between the vertical ground reaction force variables and validated functional measures.

Interpretation

Participants recovering from a hip fracture compensated using their arms and the uninvolved side to perform a Sit to Stand. Lower extremity movement strategies captured during a Sit to Stand task were correlated to scales used to assess function, balance and falls risk.

Keywords: Biomechanics, Hip fracture, Rehabilitation, Falls Risk

Introduction

Studies document the difficulties in restoring health and functional ability after a hip fracture.(Orwig et al., 2006, Magaziner et al., 2003, Hall et al., 2000) Most hip fractures in the elderly are a result of a fall, and once a subject suffers a hip fracture up to 53.3 % are reported to fall again.(Shumway-Cook et al., 2005) The fall risk of participants with a hip fracture is associated with accelerated loss of functional status compared to an age matched cohort.(Magaziner et al., 2003) Depending on which physical measure is used only 25 to 75 % of participants achieve their prior functional status 1 to 2 years after a hip fracture.(Magaziner et al., 2003) Studies have tended to focus on measures of impairments, balance, and function (i.e. Timed Up and Go, Berg Balance Scale) to establish status after hip fracture not movement strategies related to the side of injury. However, the problems associated with balance, function, and falls suggest atypical movement strategies may play an important role in determining recovery.

Biomechanical measures have the ability to capture specific aspects of movement strategy during a dynamic task, such as sit to stand, which may enhance current clinical measurement.(Lindemann et al., 2007, Etnyre and Thomas, 2007) Lower extremity movement strategies, such as bilateral force output, have been defined using the vertical ground reaction force (vGRF) during a sit to stand task.(Mazza et al., 2006, Lindemann et al., 2007) For example Lindeman et al(Lindemann et al., 2007) evaluated the summed vGRF under both feet during a STS task, which they argued represent a bilateral lower extremity pushing strategy, as a person transitions from sitting to standing. Further, average vertical power was correlated to a seated strength test (r=0.6).(Lindemann et al., 2007) A combination of vGRF variables (i.e. rate of force development (RFD), average power and maximum vGRF) predicted time to reach an upright posture (r2 = 0.37) in “very old” participants (average age 82.5 years old). However, these studies were not performed on participants recovering from a hip fracture. Yet, because of learning effects or weakness as a result of a hip fracture, alterations in lower extremity movement patterns may occur that are detected by average vertical power and vGRF variables. Further, in participants recovering from a hip fracture, unilateral, atypical, lower extremity movement patterns may show associations with physical function and balance.

Recent studies suggest that asymmetry in lower extremity movement strategies measured during a Sit to Stand (STS) task may influence balance and function.(Gilleard et al., 2008, Lundin et al., 1995, Portegijs et al., 2006, Portegijs et al., 2008) In community dwelling elderly participants, asymmetries in “explosive power” of leg muscles (e.g. measured during a seated task) are higher in fallers as compared to non-fallers (Portegijs et al., 2006, Skelton et al., 2002), and participants with mobility limitation compared to participants without mobility limitation. (Portegijs et al., 2006, Skelton et al., 2002) These asymmetries in lower extremity “leg extensor power” are hypothesized to influence movement strategies, effecting balance and falls risk. (Portegijs et al., 2006, Skelton et al., 2002) Participants with hip fracture show even greater asymmetries associated with leg extensor power on the fractured side than community dwelling elderly.(Portegijs et al., 2008) Although not studied, these results imply that asymmetry in leg extensor power measured non-weight bearing may carry over to functional tasks such as the sit to stand. In healthy adults, studies noted mild asymmetry (<10%) of joint movements and loading during a STS task.(Lundin et al., 1995, Gilleard et al., 2008) Therefore, large asymmetries (>20%) of leg extensor power known to occur in participants after a hip fracture are anticipated to result in significant side to side differences in lower extremity movement patterns. These differences in movement patterns are theorized to contribute to balance and functional deficits.(Portegijs et al., 2008) Few previous studies assessed the STS task in participants after a hip fracture.(Lauridsen et al., 2002, Sherrington and Lord, 2005) And no studies were found that 1) allowed the use of hands and 2) used unilateral vGRF readings. The clinical utility of capturing movement strategies using the vGRF would be supported by preliminary studies that demonstrate differences in defined groups of hip fracture participants and correlations among vGRF variables captured during a STS task and clinical measures of balance, falls risk and function. Further, marked differences between hip fracture (HF) participants and elderly controls (EC) based on vGRF variables may indicate incomplete recovery despite reaching functional independence with common tasks (e.g. sit to stand transfers).

The purpose of this study was to compare vGRF variables during STS between controls and a group of hip fracture participants recently discharged from rehabilitation that were community dwelling. A priori the selected vGRF features were chosen to represent the preparation and rising phases of the STS task.(Lindemann et al., 2007) The vGRF variables were hypothesized to show lower Rate of Force Development (RFD) and lower symmetry (asymmetry) in the participants recovering from a hip fracture compared to controls. To address the secondary purpose, based on previous studies of controls, participants recovering from a hip fracture were expected to show moderate correlations (r = 0.5 – 0.7) between vGRF variables (unilateral and bilateral) and validated measures of balance, falls risk and function (Timed up and go (TUG), Berg Balance Scale (BERG), Gait Speed(GS), and Lower Extremity Measure(LEM))(Lindemann et al., 2007, Guralnik et al., 1994).

Methods

Participants

A convenient sample of 28 community dwelling elderly participants participated in this study after being informed of the studies risks and benefits (research participants review board protocol # RSRB00013729). Participants recovering from hip fracture included 14 participants that met the following criteria: within 12 months of fracture, discharged from home care physical therapy, between 55 – 86 years of age, who were community dwelling (Table 1). A screening exam was performed that required 1) that participants have a equal to or greater than 4/5 knee extension manual muscle testing, 2) were able to lie flat on a plinth and have their hip and knee flexed to 100 degrees (past vertical) assessed visually and 3) iliac crest heights in standing were grossly equal assessed visually. The intent of this screening was to eliminate large leg length discrepencies (>1.5cm) and severe functional limitations. Of the 14 participants, 6 had a partial hip replacement (distal component only), 2 had a total hip replacement, and 6 had open reduction internal fixation of the femoral shaft. Participants were excluded for known neurologic (e.g. Cerebral Vascular Accident, vestibular disorders) or cardiovascular (heart disease, congestive heart failure) co-morbidities. In addition, participants were excluded for specific musculoskeletal diagnosis that impaired lower extremity function (i.e. chronic low back pain) other than hip fracture.

Table 1.

Average (standard deviations) for performance based and self report measures.

| Variable | Control n=14 | Hip Fractures n=14 | p-values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics@ | |||

| Age | 69.36 (10.94) | 76.43 (7.11) | 0.06 |

| Height (m) | 1.67 (0.08) | 1.65 (0.14) | 0.67 |

| Mass (kg) | 69.87 (8.09) | 69.63 (15.32) | 0.58 |

| BMI | 24.9 (3.31) | 25.74 (4.41) | 0.35 |

| Fracture duration (months) | N/A | 4.59 | |

| Gender | 11 F/3 M | 9 F/5 M | |

| Force Plate | |||

| Sit to Stand Time (s) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.5(0.4) | 0.03 |

| Performance Based# | |||

| Timed up & go (s) | 7.9 (1.9) | 13.5 (4.8) | <0.001 |

| Berg Balance Scale (points) | 54.9 (2.0) | 47.1 (7.4) | 0.002 |

| 6 Meter Walk (m/s) | 1.3 (0.2) | 0.85 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Self Report# | |||

| Lower Extremity Measure (%) | 93.9 (2.6) | 82.5 (6.7) | <0.001 |

Control participants were included if they were between the ages of 55–86 years old, had a TUG score of less than 14 s, and were community dwelling. The control participants were comparable to the hip fracture group for average age, height and mass (Table 1). A TUG time of less than 14 s was adopted for this study based on a previous study suggesting times greater than 14 s was an indicator of the risk of falling in community dwelling frail participants.(Shumway-Cook et al., 2000) The control participants also met the same criteria applied to the participants recovering from a hip fracture. An a priori power analysis using pilot data suggested 10 participants/group would be adequate to achieve 80 % power.

Functional & Balance Assessment

A set of validated tests that are used to document functional recovery in participants with hip fracture included performance based measures (TUG, Gait Speed,(Binder et al., 2004, Mangione et al., 2005) BERG(Kulmala et al., 2007, Hall et al., 2000, Tinetti et al., 1997)) and a self report measure (LEM(Jaglal et al., 2000)). For the TUG, participants were asked to sit on a standard chair. On cue, participants rose from the chair, walked 3 meters to a designated line on the floor and returned to their initial seated position. A stop watch was used to time each participant’s performance. The TUG test has shown excellent reliability and validity in frail elderly participants and participants with hip fracture.(Jaglal et al., 2000, Morris et al., 2001)

Gait speed is commonly used to document outcomes in elderly participants after hip fracture. (Binder et al., 2004, Mangione et al., 2005) From a standing position, participants traversed a 6 meter distance as fast as they could, continuing at least 2 complete steps before stopping. The time was clocked with a stopwatch and 6 meters was divided by the time to calculate gait speed (m/s). This simple measure is reliable and valid for inferences related to ADL function in geriatric patients.

The BERG is a performance based measure that is used frequently to identify risk of falling and balance in a wide variety of elderly participants including those with hip fracture.(Kulmala et al., 2007, Hall et al., 2000, Tinetti et al., 1997, Berg et al., 1992) Higher scores are awarded for independent performance that meets specific time or distance requirements.

The Lower Extremity Measure (LEM) is a validated self report scale for assessment of functional mobility in participants with hip fracture.(Jaglal et al., 2000) This 30 item self-report questionnaire was evaluated for reliability, face validity, criterion validity, construct validity and responsiveness in elderly participants with hip fractures.(Jaglal et al., 2000) Scores of 75 – 85 indicate moderate limitations in functional mobility and scores above 85 indicate normal functional ability.

Instrumented Sit to Stand Test

Participants vary their performance based on initial position for the STS task, therefore several variables were controlled.(Janssen et al., 2002) The height of the seat was adjusted (5 cm increments from 45 cm to 60 cm) as close as possible to achieve a 90/90, hip/knee angle. Participants’ hands were placed at the edge of the arm-rest that was fixed at 20 cm above the seat. Participants were seated on the front ½ of an instrumented chair where the mid-length of their thigh was aligned with the edge of the chair and their ankles were placed at approximately 15 degrees of dorsiflexion. Participants were instructed to use their arms as they normally would during the task, while standing as “quickly as possible.” One practice trial was performed before recording data from three STS trials. The STS task was repeated at the beginning and end of the data collection using the same procedures to assess repeatability.

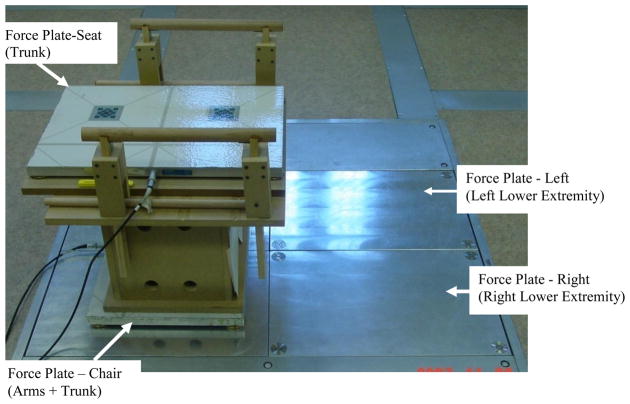

Four force plates (2 Model # 92868, and 2 Model # 9865C Kistler, Instrument Corp., Amherst, NY) integrated into a custom built chair (Figure 1) were used to capture the Vertical Ground Reaction Force (vGRF variables). Two force plates were flush with the floor to record vGRF under each limb (vGRFinvolved and vGRFuninvolved). The chair was placed on top of a force plate that recorded the forces acting through the chair (vGRFchair) (i.e. the sum of body weight and arms contribution). A force plate mounted on the seat recorded (vGRFseat) specific to the buttock. During each data collection the vGRF of each force plate was recorded at sampling rate of 1000 Hz using the Motion Monitor Software (Innsport Training, Inc., Chicago, IL). A separate digital video camera (model DCR-TRV240, Sony), synchronized with vGRF data, frame rate =30 samples/second, was used to acquire sagittal plane video of participants during the STS task. The camera was mounted on a tripod that allowed for adjustment to seat height. Three levels mounted on the tripod in each plane were used to align the camera “square” with the seat, minimizing the effects of parallax. Pixels were converted to meters using a standardized vertical distance marked on the chair.

Figure 1.

The instrumented chair incorporated 4 force plates to measure vertical ground reaction forces under the seat, chair, right lower extremity and left lower extremity.

From the four force plates and video recordings the following calculations were made to capture movement strategies:

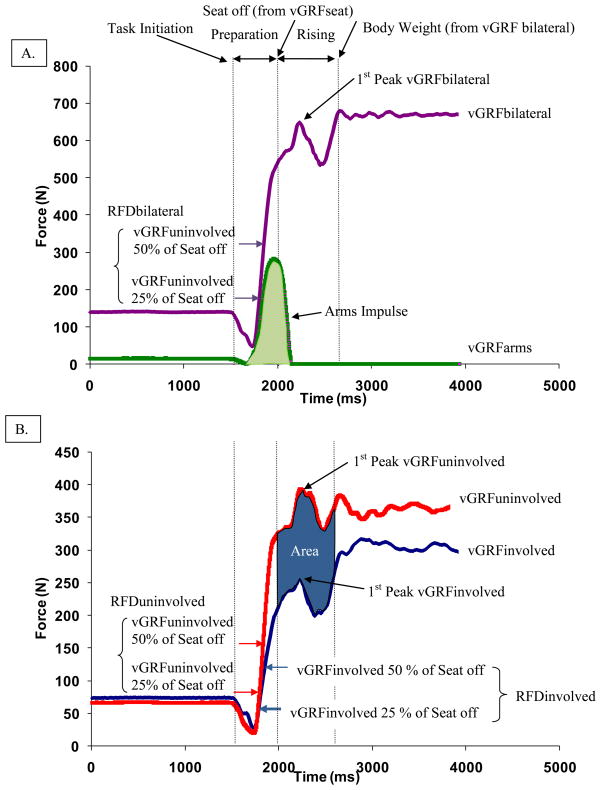

1. Phases of Sit to Stand Task

As used in recent studies (Etnyre and Thomas, 2007, Lindemann et al., 2007) two phases of the sit to stand task were identified from the summed vGRFinvolved and vGRFuninvolved sides (vGRFbilateral = vGRFinvolved + vGRFuninvolved) (Figure 2). The preparatory phase began with a 5 N decrease in the vGRFbilateral, which is the start of a countermovement of the trunk/feet backwards. The end of the preparatory phase (beginning of the rising phase) occurs at seat off, marked as the instant vGRFseat goes below 5 N. The rising phase ends when vGRFbilateral reaches body weight, after the 1st peak of vGRFbilateral (Figure 2). The STS time was the time from the beginning of the preparatory phase to the end of the rising phase.

Figure 2.

The following figures are an example of a single participant trial A. The summed vertical ground reaction forces(vGRF) under the right and left lower extremity(vGRFbilateal) and arms (vGRFarms) are shown. Task initiation and the end of the rising phase was determined from vGRFbilateral. Seat off, which determines the transition point between the preparation and rising phases, was determined from the seat force plate (vGRFseat). The rate of force development (RFDbilateral) was calculated as the slope from 25 to 50 % of the force value at seat off. The arms impulse was the area under the vGRFarms. B. The unilateral measures of vGRFinvolved/uninvolved were determined from the left and right force plates. For the preparation phase the RFD invovled/uninvolved was calculated similar to RFD bilateral. Symmetry during the rising phase was calculated as the area between the vGRFinvolved and uninvolved throughout the rising phase.

2. Arms impulse

The arms contribution (vGRFarms) was calculated as the difference between vGRFchair and vGRFseat (vGRFarms = vGRFchair – vGRFseat). Known weights were loaded onto the chair arm rests and seat to determine the validity of vGRFarms. Differences between known weights and the vGRFarms were less than 2 N for a variety of loads. The arms impulse was defined as the Area under the vGRFarms starting at the first increase (> 5N) in force after task initiation, ending when vGRFarms reached below 5 N (Figure 1). Arms impulse describes the vertical upper extremity contribution during the STS task and occurs in both the preparation and rising phases.

3. Lower Extremity vGRF Variables

To capture lower extremity movement strategies, unilateral and bilateral vGRF variables were identified. During the preparation phase the RFD (N/s) was calculated as the slope between 25% and 50% of the vGRF achieved at seat off for vGRFbilateral (RFDbilat), vGRFinvolved (RFDinvolved) and vGRFuninvolved (RFDuninvolved).(Etnyre and Thomas, 2007, Lindemann et al., 2007) From vGRFbilateral and digital video data the average power during the rising phase was calculated as described in previously.(Lindemann et al., 2007). The difference in contribution of each lower extremity to the rising phase was captured using a symmetry measure, where the Area between the vGRFinvolved and the vGRFuninvolved, was calculated over the rising phase (Figure 2). A lower Area suggests greater symmetry or relatively equal vGRF under both limbs and higher Areas suggest greater asymmetry or greater reliance on one of the lower extremities. The test re-test reliability determined using the intraclass correlation coefficient for STS vGRF variables ranged from 0.84 to 0.91 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (3,1) (95 % C.I.) of vertical ground reaction force variables for each group and all subjects considered together.

| Variables | All Subjects (n=28) | Control (n=14) | Hip Fracture (n=14) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preparation Phase | |||

| RFD Involved (N/s)/(kg) | 0.91 (0.81 to 0.96) | 0.90 (0.71 to 0.97) | 0.82 (0.53 to 0.94) |

| RFD Uninvolved (N/s)/(kg) | 0.84 (0.69 to 0.92) | 0.82 (0.52 to 0.94) | 0.90 (0.71 to 0.97) |

| RFD Bilateral (N/s)/(kg) | 0.89 (0.76 to 0.95) | 0.88 (0.57 to 0.94) | 0.82 (0.50 to 0.95) |

| Rising Phase | |||

| Power (W)/(kg) | 0.88 (0.75 to 0.94) | 0.87 (0.65 to 0.96) | 0.87 (0.65 to 0.96) |

| Area (N*s)/kg | 0.86 (0.71 to 0.93) | 0.85 (0.58 to 0.95) | 0.82 (0.51 to 0.94) |

| Peak Force – uninvolved side (N/kg) | 0.80 (0.61–0.90) | 0.73 (0.16–0.92) | 0.88 (0.66–0.96) |

| Peak Force – involved side (N/kg) | 0.88 (0.76–0.94) | 0.80 (0.39–0.94) | 0.91 (0.75–0.97) |

| Preparation and Rising Phases | |||

| Arms Impulse (N*s)/(kg) | 0.86 (0.72 to 0.94) | 0.77 (0.37 to 0.92) | 0.86 (0.62 to 0.95) |

RFD = Rate of Force Development, Area= magnitude of the difference between vGRFinvolved and vGRFuninvolved.

Statistical Analysis

To establish the status of the Hip fracture group performance based (TUG, GS, BERG) and self report (LEM) scores were compared to the control group using a MANOVA. The dependent variables of the MANOVA included TUG, GS, BERG, LEM and STS time and the independent variable was group (control and hip fracture). Similarly, to determine the ability of the vGRF variables during the STS task to discriminate the Hip Fracture group a MANOVA was used. First, all vGRF variables were normalized to body mass. All variables were evaluated for normality, and transformed if necessary to generate a normal distribution, prior to running the MANOVA’s. There were no differences attributable to side for any of the STS variables in the control group, so the right was the “involved side” and left the “uninvolved side” for the controls. For this MANOVA, the dependent variables included the RFDinvolved, RFDuninvolved, RFDbilateral, Power, Area, 1st Peak vGRFinvolved, 1st Peak vGRFuninvolved and Arms Impulse and the independent variable was group (control and hip fracture). The control group was marginally younger (6 years, p = 0.06) therefore, the covariate considered in both MANOVA analysis was age. MANOVA analyses were assigned a significant p value of < 0.05. For the hip fracture group, correlations between the vGRF variables and performance based and the self report measures were assessed using a Pearson Product Moment correlation. All correlations were also assessed visually for extreme values. In the case of extreme values (outliers) defined as > 2 SD from the mean, the analysis was run with the outlier removed. The SPSS v14 software was used to run all analysis.

Results

Participant Status

The performance and self report measures all showed significant differences between the participants recovering from a hip fracture compared to the controls (Wilks’ Lambda = 7.29, p = 0.002) (Table 1). The hip fracture group had higher TUG (difference between group means = 5.6 s, confidence interval (C.I.) = 2.6 s to 8.6 s) and lower Gait Speed (difference between group means = 0.46 m/s, C.I. = 0.29 m/s to 0.63 m/s) compared to controls. On the BERG Balance Scale the hip fracture group also demonstrated significantly lower scores (difference between group means = 7.8, C.I. = 3.4 to 12.6) compared to controls. Finally, on the LEM, the hip fracture group reported significantly lower functional ability (difference between group means = 11.4 %, C.I. = 8.8 % to 16.8 %).

Sit to Stand Vertical Ground Reaction Force Variables

There were significant differences between the control and hip fracture group in both the preparation and rising phase variables of the STS task for both the involved and uninvolved limbs (Table 3). During the preparation phase the RFDinvolved was significantly lower in the participants recovering from a hip fracture compared to the controls (difference between group means = 12.9 (N/s)/kg, C.I. = 3.8 (N/s)/kg to −20.9 (N/s)/kg). During the rising phase the Area was significantly lower for the controls compared to the hip fracture group (Area - difference between group means = 0.57 (N*s)/kg, C.I.= 0.11 (N*s)/kg to 0.95 (N*s)/kg) The 1st peak vGRFinvolved was significantly higher for the controls compared to the hip fracture group (1st peak vGRFinvolved - difference between group means = 0.58 N/kg, C.I.= 0.16 N/kg to 1.2 N/kg). The Arms Impulse, which spans both the preparation and rising phases was significantly higher in the participants recovering from a hip fracture (difference between group means = 0.35 (N*s)/kg, C.I.= 0.02 (N*s)/kg to .68 (N*s)/kg). When age was entered as a covariate the results of the MANOVA did not change.

Table 3.

Average (standard deviations) of ground reaction force variables

| Variables | Control (n=14) | Hip Fractures (n=14) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preparation Phase | |||

| RFDInvolved (N/s)/kg | 35.7 (12.4) | 22.8 (8.5) | 0.008 |

| RFDUninvolved(N/s)/kg | 32.8 (9.3) | 33.4 (11.1) | 0.349 |

| RFDBilateral (N/s)/kg | 64.9 (17.2) | 53.2 (17.8) | 0.089 |

| Rising Phase | |||

| Power (W)/kg | 5.0 (1.8) | 4.4 (1.3) | 0.256 |

| Area (N*s)/kg | 0.59 (0.21) | 1.16 (0.84) | 0.021 |

| 1st Peak vGRFinvolved (N/kg) | 5.1 (0.54) | 4.5 (0.82) | 0.004 |

| 1st Peak vGRFuninvolved (N/kg) | 5.1 (0.41) | 5.3 (0.86) | 0.371 |

| Preparation and Rising Phases | |||

| Arms Impulse (N*s)/kg | 0.86 (0.20) | 1.20 (0.58) | 0.040 |

Rate of Force Development (RFD), Average power during rising phase (Power), Vertical ground reaction force (vGRF).

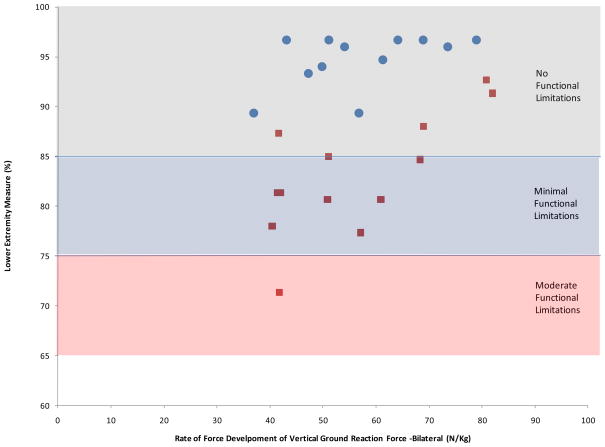

Correlation of vGRF with Performance based and Self Report Measures

In the preparation phase the RFDinvolved and RFDbilateral were significantly correlated to the LEM and Gait Speed (Table 4). A single outlier was identified and therefore for all the correlations reported here this subject was removed from the data set. As RFD increased (RFDinvolved and RFDbilateral) LEM also increased. In the rising phase both 1st Peak vGRFinvolved (LEM, r=0..499; GS, r=0.517) and Area (LEM, r= −0.551; GS, r= −0.443) showed significant correlations with performance based measures. As the 1st Peak vGRFinvolved increased so did LEM and GS. As Area increased LEM and Gait Speed decreased.

Table 4.

Correlations (p-values) of vertical ground reaction force variables and validated scales N=27.

| Variables | Berg Balance Scale | Timed Up & Go | Gait Speed | Lower Extremity Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preparation Phase | ||||

| RFD Involved(N/s)/kg | 0.433 (0.061) | −0.357 (0.068) | 0.579** (0.002) | 0.593** (0.001) |

| RFD Uninvolved(N/s)/kg | −0.083 (0.679) | 0.078 (0.701) | −0.028 (0.891) | 0.074 (0.714) |

| RFD bilateral(N/s)/kg | 0.238 (0.232) | −0.301 (0.127) | 0.417* (0.030) | 0.487* (0.010) |

| Rising Phase | ||||

| Power (W)/kg | 0.277 (0.162) | −0.323 (0.101) | 0.269 (0.175) | 0.192 (0.338) |

| Area (N*s)/kg | −0.288 (0.145) | 0.334 (0.089) | −0.443* (0.021) | −0.551** (0.003) |

| 1st Peak vGRFinvolved (N/kg) | −0.310 (0.116) | −0.349 (0.0574) | 0.499** (0.008) | 0.517** (0.004) |

| 1st Peak vGRFuninvolved (N/kg) | 0.223 (0.264) | −0.057 (0.777) | −0.023 (0.909) | −0.280 (0.157) |

| Preparation and Rising Phases | ||||

| Arms Impulse (N*s)/kg | −0.104 (0.606) | 0.010 (0.961) | −0.023 (0.908) | −0.307 (0.286) |

RFD = rate of force development

Discussion

The findings of this study document that participants after discharge from rehabilitation use altered movement strategies that include higher arm impulse, lower RFDinvolved and lower peak vertical force of the involved limb. Despite these compensations participants were not able to achieve similar STS times as controls. The hypothesis that movement strategy captured during a STS task using the vGRF would be associated with performance based and self report measures reflective of balance, falls risk and function was partially supported. Measures of physical function (i.e. LEM and Gait speed) were moderately correlated with vGRF variables however balance and falls risk was not correlated with vGRF variables. This suggests that balance/falls risk may not be associated with STS ability. Previous studies documented side to side differences in lower extremity power during seated tests, but did not test whether side to side differences in lower limb function also occurred during a functional task.(Portegijs et al., 2006, Portegijs et al., 2008, Skelton et al., 2002) This study documents that asymmetry of lower limb movement strategy defined using vGRF variables is associated with hip fracture during a common functional activity. The performance based and self report scores support discharge from rehabilitation (i.e. independence with functional tasks), however, this data suggests compensations with arms and greater reliance on the uninvolved side persist.

Although performance based and self report scores were lower for participants recovering from hip fracture compared to elderly controls, the functional status of these participants was moderately limited to normal (no limitation). For example no participants used assistive devices and on the LEM all but 1 subject was either in the moderate limitation (75 to 85) or no limitation category (> 85), functionally justifying discharge(Jaglal et al., 2000). However, only 1 of the participants recovering from a hip fracture achieved a Gait Speed equal to or above 1.22 m/s (the minimum required to cross an intersection), where 10 of 14 of the controls achieved this speed. The TUG scores (average for hip fracture group = 13.5 s) compliment BERG scores indicating continued balance problems in the hip fracture group (Table 1). These measures suggest the study participants recovering from a hip fracture are characterized by continued balance problems, however, possess moderate to good functional abilities.

The vGRF variables associated with arms and side distinguish these participants recovering from hip fracture. The data suggest participants partially depended (Table 3) on compensations with their arms and a greater relative contribution of the uninvolved side. While the RFDinvolved was 30% lower than controls, the RFDuninvolved was equal to the control participants (Table 3). This discrepancy between the involved and uninvolved side continued into the rising phase, where the Area between the vGRFinvolved and vGRFuninvolved for the hip fracture group were nearly double that of the controls (Table 3). The higher Area is associated with a significantly lower 1st peak vGRFinvolved, confirming that greater Area is a result of a lower vGRFinvolved. Despite these strong differences in the vGRF patterns specific to side, the participants recovering from a hip fracture achieved a minimally lower STS time. Other studies of lower extremity orthopedic problems (e.g. TKR) have also noted increased reliance on the uninvolved side and suggested this compensation with the uninvolved leg is a learned pattern.(Farquhar et al., 2008)

The failure of arms to induce symmetry of lower extremity force output is interesting. A common compensation used by elderly to rise from a chair is hands use.(Bohannon and Corrigan, 2003) The use of arms has also been found to significantly reduce the knee extension moment by 20 %, explaining the utility of this compensation.(Anglin and Wyss, 2000, Schultz et al., 1992) In this study the Arms Impulse generated by the hip fracture group was 0.39 N*s/kg higher or 45 % higher than the control groups average (Table 3). Theoretically the reduction in lower extremity demand due to the hands use may minimize the influence of weakness on the STS task. Despite this effect attributable to hands use, differences in lower extremity force output existed. One explanation may be that lower extremity weakness was present beyond what hands use can compensate for. Alternatively, the higher reliance on the uninvolved side may be the result of a learned pattern that arises as a result of the injury that is not influenced by hands use. Future studies may consider exploring the influence of clinical variables (strength and range of motion) as a cause of decreased lower extremity force output.

During the preparation phase, the correlations of the vGRF variables were significant for gait speed and self report of function but not balance scales (Berg and TUG). During the preparation phase the rate of force development variables (RFDinvolved and RFDbilateral) were modestly correlated (r = 0.42– 0.50) with gait speed and self report of function (Table 4). This correlation supported the premise that the rate of the lower extremity push movement strategy during a sit to stand task may also be important during other activities (e.g. gait).(Lindemann et al., 2007) The correlation with self report scores, although modest, also suggest that rate of force development may influence participants perceptions about their functional ability.

Similar to the preparation phase, during the rising phase the correlations between the vGRF variables were significant for gait speed and self report of function but not scales reflective of balance. This was not expected. During the rising phase, the AREA measure documents an imbalance in lower limb force output after seat off. Previous studies, based on non-weight bearing assessment of lower extremity power, suggested that asymmetry of lower limb force output occurs during tasks, contributing to poor balance, and possibly, leading to falls.(Portegijs et al., 2006, Portegijs et al., 2008, Skelton et al., 2002) This association was not supported in this study. However, there were modest correlations (r = −0.44 to 0.52) of Area and peak force on the involved limb with gait speed and self report of function. Similar to rate of force development, asymmetries in force output may carry over to gait and be perceived by participants.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study is specific to community dwelling elderly participants with good balance performance (i.e. BERG Balance scores above the cutpoint for falls risk) and participants recovering from a hip fracture. Longitudinal studies of participants with hip fractures are more desirable to avoid pitfalls in using controls to determine potential outcomes from injury. In addition, movement strategies defined by the vGRF variables are not specific to a joint. Biomechanical variables specific to a joint (e.g. angles, moments and power) or muscle (electromyography) may be an important to assessmovement strategies in participants recovering from a hip fracture. Because shear forces (anterior/posterior) were not determined it is unknown whether shear forces contribute to asymmetry of lower extremity force output. The cause of slower force development during the preparation phase and asymmetry during the rising phase is not addressed in this study. Previous studies suggested a combination of strength, sensorimotor, balance and psychological measures influence STS ability in elderly participants.(Lord et al., 2002) Future, studies may consider evaluating the effects of these factors on vGRF variables during a STS task.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the vGRF variables during a STS task suggested that moderate to high functioning participants recovering from a hip fracture rely on the uninvolved side and upper extremity support to achieve a rapid STS task. Further, lower extremity movement strategy as defined by vGRF variables were correlated to function but not balance. Although not specific to a joint, the vGRF appears to be an effective method of capturing movement strategy specific to a limb or both limbs after a hip fracture.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot of bilateral rate of force development (vGRFbilateral) and the Lower Extremity Measure (LEM). Blue circles represent elderly control group and red squares represent hip fracture group.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for support for this research from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Arthritis and Skin Diseases, grant award “Center of Research Translation” (CORT) 1P50AR05041-02. We are also thankful to Ryan Yelle and Jen Churey for assistance with data analysis and Kelly Unsworth for assistance with subject recruitment.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jeff Houck, Department of Physical Therapy, Ithaca College Rochester Center, 1100 South Goodman St., Rochester, NY 14618 USA.

Janet Kneiss, Department of Physical Therapy, MGH Institute of Health Professions, Charlestown Navy Yard, 36 First Avenue, Boston, MA 02129.

Susan V. Bukata, Department of Orthopaedics, University of Rochester Medical Center, Box 665, 601 Elmwood Ave, Rochester, NY 14642 USA.

J. Edward Puzas, Department of Orthopaedics, University of Rochester Medical Center, Box 665, 601 Elmwood Ave, Rochester, NY 14642 USA.

References

- ANGLIN C, WYSS UP. Arm motion and load analysis of sit-to-stand, stand-to-sit, cane walking and lifting. Clinical Biomechanics. 2000;15:441–8. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(99)00093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERG KO, WOOD-DAUPHINEE SL, WILLIAMS JI, MAKI B. Measuring balance in the elderly: validation of an instrument. Canadian Journal of Public Health Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique. 1992;83(Suppl 2):S7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BINDER EF, BROWN M, SINACORE DR, STEGER-MAY K, YARASHESKI KE, SCHECHTMAN KB. Effects of extended outpatient rehabilitation after hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial.[see comment] JAMA. 2004;292:837–46. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOHANNON RW, CORRIGAN DL. Strategies Community Dwelling Elderly Women Employ to Ease the Task of Standing Up From Household Surfaces. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2003;19:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- ETNYRE B, THOMAS DQ. Event standardization of sit-to-stand movements. Physical Therapy. 2007;87:1651–66. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060378. discussion 1667–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FARQUHAR SJ, REISMAN DS, SNYDER-MACKLER L. Persistence of altered movement patterns during a sit-to-stand task 1 year following unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Physical Therapy. 2008;88:567–79. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILLEARD W, CROSBIE J, SMITH R. Rising to stand from a chair: symmetry, and frontal and transverse plane kinematics and kinetics. Gait & Posture. 2008;27:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GURALNIK JM, SIMONSICK EM, FERRUCCI L, GLYNN RJ, BERKMAN LF, BLAZER DG, SCHERR PA, WALLACE RB. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. Journal of Gerontology. 1994;49:M85–94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALL SE, WILLIAMS JA, SENIOR JA, GOLDSWAIN PR, CRIDDLE RA. Hip fracture outcomes: quality of life and functional status in older adults living in the community. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Medicine. 2000;30:327–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2000.tb00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAGLAL S, LAKHANI Z, SCHATZKER J. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the lower extremity measure for patients with a hip fracture. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery - American Volume. 2000;82-A:955–62. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200007000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANSSEN WG, BUSSMANN HB, STAM HJ. Determinants of the sit-to-stand movement: a review. Physical Therapy. 2002;82:866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KULMALA J, SIHVONEN S, KALLINEN M, ALEN M, KIVIRANTA I, SIPILA S. Balance confidence and functional balance in relation to falls in older persons with hip fracture history. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy. 2007;30:114–20. doi: 10.1519/00139143-200712000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAURIDSEN UB, DE LA COUR BB, GOTTSCHALCK L, SVENSSON BH. Intensive physical therapy after hip fracture. A randomised clinical trial. Danish Medical Bulletin. 2002;49:70–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDEMANN U, MUCHE R, STUBER M, ZIJLSTRA W, HAUER K, BECKER C. Coordination of strength exertion during the chair-rise movement in very old people. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences. 2007;62:636–40. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.6.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LORD SR, MURRAY SM, CHAPMAN K, MUNRO B, TIEDEMANN A. Sit-to-stand performance depends on sensation, speed, balance, and psychological status in addition to strength in older people. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences. 2002;57:M539. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.8.m539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUNDIN TM, GRABINER MD, JAHNIGEN DW. On the assumption of bilateral lower extremity joint moment symmetry during the sit-to-stand task. Journal of Biomechanics. 1995;28:109. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGAZINER J, FREDMAN L, HAWKES W, HEBEL JR, ZIMMERMAN S, ORWIG DL, WEHREN L. Changes in functional status attributable to hip fracture: a comparison of hip fracture patients to community-dwelling aged. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157:1023–31. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANGIONE KK, CRAIK RL, TOMLINSON SS, PALOMBARO KM. Can elderly patients who have had a hip fracture perform moderate- to high-intensity exercise at home? Physical Therapy. 2005;85:727–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAZZA C, STANHOPE SJ, TAVIANI A, CAPPOZZO A. Biomechanic modeling of sit-to-stand to upright posture for mobility assessment of persons with chronic stroke. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2006;87:635. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORRIS S, MORRIS ME, IANSEK R. Reliability of measurements obtained with the Timed “Up & Go” test in people with Parkinson disease. Physical Therapy. 2001;81:810–8. doi: 10.1093/ptj/81.2.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORWIG DL, CHAN J, MAGAZINER J. Hip fracture and its consequences: differences between men and women. Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 2006;37:611–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PORTEGIJS E, SIPILA S, PAJALA S, LAMB SE, ALEN M, KAPRIO J, KOSEKENVUO M, RANTANEN T. Asymmetrical lower extremity power deficit as a risk factor for injurious falls in healthy older women. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:551–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00643_6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PORTEGIJS E, SIPILA S, RANTANEN T, LAMB SE. Leg extension power deficit and mobility limitation in women recovering from hip fracture. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2008;87:363–70. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318164a9e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHULTZ AB, ALEXANDER NB, ASHTON-MILLER JA. Biomechanical analyses of rising from a chair. Journal of Biomechanics. 1992;25:1383–91. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(92)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHERRINGTON C, LORD SR. Reliability of simple portable tests of physical performance in older people after hip fracture. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2005;19:496–504. doi: 10.1191/0269215505cr833oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHUMWAY-COOK A, BRAUER S, WOOLLACOTT M. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the Timed Up & Go Test. Physical Therapy. 2000;80:896–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHUMWAY-COOK A, CIOL MA, GRUBER W, ROBINSON C. Incidence of and risk factors for falls following hip fracture in community-dwelling older adults. Physical Therapy. 2005;85:648–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SKELTON DA, KENNEDY J, RUTHERFORD OM. Explosive power and asymmetry in leg muscle function in frequent fallers and non-fallers aged over 65. Age & Ageing. 2002;31:119–25. doi: 10.1093/ageing/31.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TINETTI ME, BAKER DI, GOTTSCHALK M, GARRETT P, MCGEARY S, POLLACK D, CHARPENTIER P. Systematic home-based physical and functional therapy for older persons after hip fracture. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 1997;78:1237–47. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]