Abstract

The current study tests a model of risk for anxiety in fearful toddlers characterized by the regulation of the intensity of withdrawal behavior across a variety of contexts. Participants included 111, low-risk, 24-month-old toddlers followed longitudinally each year through the fall of their kindergarten year. The key hypothesis was that being fearful in situations that are relatively low in threat (i.e., are predictable, controllable, and in which children have many coping resources) is an early precursor to risk for anxiety development as measured by parent and teacher report of anxious behaviors in kindergarten. Results supported the prediction such that it is not how much fear is expressed, but when the fear is expressed and how it is expressed that is important for characterizing adaptive behavior. Implications are discussed for a model of risk that includes the regulation of fear, the role of eliciting context, social wariness, and the importance of examining developmental transitions, such as the start of formal schooling. These findings have implications for the way we identify fearful children who may be at risk for developing anxiety-related problems.

A substantial number of children and adolescents develop internalizing disorders such as anxiety (Albano, Chorpita, & Barlow, 1996). Community sample prevalence rates for anxiety disorders in children as young as four range from 7.4–17.3% and rates are even higher for subclinical levels and symptoms (Angold, Costello, Farmer, Burns, & Erkanli, 1999; Ollendick & Vasey, 1999; Weisz & Hawley, 2002). Although there are a number of environmental risk factors that have been identified, including parental psychopathology, exposure to trauma, maltreatment, and poverty (Egger & Angold, 2006); there is also considerable work that has focused on individual differences in emotionality that emerge early (e.g., temperament) and the elevated risk for development of internalizing symptoms later in childhood. This individual differences model guides the current study. Individual differences in temperament, biosocial risk, and biological sensitivity to context have been identified as common risk factors in developmental models of psychopathology (Bosquet & Egeland, 2006; Boyce & Ellis, 2005; Nigg, 2006; Rothbart, Posner, & Hershey, 1995). Although a great deal of work in child clinical psychology has focused on illuminating these processes within high-risk samples, our understanding of the development of anxiety disorders is not complete without an examination of risk for disorder among typically developing children (Cicchetti, 1993; 1994). The current study was designed to address risk for anxious behaviors among low-risk children.

In temperament-psychopathology models, much of the empirical literature has highlighted fearful temperament as a potential risk factor (Biederman, Rosenbaum, Chaloff, & Kagan, 1995). To date, defining and measuring fearful temperament has predominantly focused on assessing the intensity of fearful or shy behaviors, and identifying children whose behaviors are relatively distinct and indicative of extreme group membership (e.g., behavioral inhibition) to identify children who may be at risk (Kagan, Reznick, & Gibbons, 1989; Stifter, Putnam, & Jahromi, 2008). Research using this approach has demonstrated that fearful temperament is related to the development of behaviors within the internalizing spectrum (Biederman et al., 2001; Schwartz, Snidman, & Kagan, 1999). The exact mechanisms by which individual differences in fearful behavior develop into anxiety symptoms are still largely unknown; so it remains unclear which fearful children are at particular risk, and why. Using a modification of the temperament and psychopathology model, this study addressed the following questions: In what way does eliciting context influence the expression of fear behavior? Is it the intensity with which children experience fear or how children express fear across different situations that predicts risk?

Fearful Temperament a Risk Factor for Anxiety

The study of individual differences in emotionality and affective behaviors in infants and young children is often synonymous with temperament research. Most researchers agree that temperament refers to stable individual differences in behavioral tendencies that appear in infancy and involve biological and heritable underpinnings (Goldsmith et al., 1987). The pioneering work of Jerome Kagan and colleagues led to the identification of two different temperament types. Behaviorally inhibited and uninhibited children were identified across a series of situations designed to assess individual differences in the intensity, frequency, and duration of approach/withdrawal tendencies that children showed in response to novelty (Garcia-Coll, Kagan, & Reznick, 1984; Kagan, Reznick, Clarke, Snidman, & Garcia-Coll, 1984; Kagan, Reznick, Snidman, Gibbons, & Johnson, 1988). Behaviorally inhibited children, representing approximately 10–20% of typically-developing children, are characteristically shy and withdrawn in novel social situations. These children also show signs of decreased activity and approach, and increased anxiety in the face of novel challenges.

Because behavioral inhibition reflects a temperamental dimension, stability in this behavioral profile should theoretically be observed (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). In empirical investigations, however, stability in temperament is typically modest and significant change is often observed. Several studies have demonstrated substantial stability in inhibited behavior throughout childhood, with 30–50% of children retaining inhibited status (Caspi & Silva, 1995; Garcia-Coll et al., 1984; Kagan et al., 1988; Pfeifer, Goldsmith, Davidson, & Rickman, 2002). Other studies have reported stability for only a limited subset of children, such as those at the extremes, or little stability for any children (Asendorpf, 1994; Davidson & Rickman, 1999; Stifter et al., 2008). Taken together, this research suggests that some of this apparent instability in temperament may be normative (Rothbart & Bates, 2006), but behaviors at the extreme tend to be more stable across time (Garcia-Coll et al., 1984; Kagan et al., 1984; Kagan et al., 1988). Indeed, conceptual models linking extremes on particular temperament dimensions with psychopathological characteristics are prominent (Nigg 2006; Rothbart, Posner, & Hershey, 1995). Thus, identification of these extremes in fearful emotionality is critical for our understanding of children’s risk for anxiety.

Studies have supported the hypothesis that fearful temperament is a major risk factor for the development of disorders in the internalizing spectrum. Schwartz and colleagues (1999) found that inhibited children were less likely to interact spontaneously with an experimenter and more likely to display generalized social anxiety symptoms compared to uninhibited children. Not all inhibited children develop anxiety symptoms, but the stability of shy-inhibited behavior dramatically increases the likelihood of developing anxiety disorders (Prior, Smart, Sanson, & Oberklaid, 2000). Overall, studies with both clinical and non-clinical samples have demonstrated a moderate association (17–34%) between inhibition and risk for anxiety disorders in childhood (Biederman et al., 2001; Hirshfeld, Rosenbaum, Biederman, Bolduc, & et al., 1992; Rosenbaum, Biederman, Bolduc-Murphy, Faraone, & et al., 1993; Rosenbaum, Biederman, Hirshfeld, Bolduc, & et al., 1991). Other studies have failed to show an association between inhibition and internalizing symptoms, especially early in development (Stifter et al., 2008). So despite a strong theoretical reason for prediction from “high fear” to internalizing symptoms, the relative modesty of this relation suggests the possibility of false positives. That is, the majority of children classified as temperamentally fearful, who are putatively at risk for internalizing disorders, never develop symptoms and may even appear to grow out of this temperament style. This may be explained in part by models suggesting that not all of these fearful children are vulnerable (Boyce & Ellis, 2005); but it is also possible that we have not yet identified the specific pattern of fearful behavior that best characterizes this vulnerability.

In line with the developmental psychopathology perspective, it is also possible that, instead of classifiable disorders, temperamentally fearful children may show failures in adaptation at important milestones that would lead to later disorder (Sroufe & Rutter, 1984). Several studies have addressed the behavior of shy and inhibited children during their transition to kindergarten with particular focus on social wariness outcomes. Inhibited children (identified at 2 years) were more restrained in behavior, spent less time proximal to peers, interacted less with peers, and spent more time hovering in the classroom and on the playground compared to uninhibited children (Reznick et al., 1986). In the classroom, inhibited children talked less, were less aggressive, and followed classroom rules more closely than uninhibited children (Rimm-Kaufman & Kagan, 2005). Thus, social withdrawal at the transition to kindergarten appears to carry significant consequences for young children, and will be examined as one outcome in the current study.

Heterogeneity of Fearful Behavior

Most theorists and researchers would agree that fear is a broad construct that includes several state and trait types of behavior as well as anxiety (Kagan, 1994). For instance, in the case of fearful temperament, one could consider motivational aspects (e.g., withdrawal, avoidance), communicative/distress behaviors (e.g., facial expressions, crying), behavioral reactions (e.g., flight or freezing), or social reactions (e.g., shyness, social reticence, social withdrawal). It has even been suggested that behavioral inhibition may not reflect high fear, but is better characterized as a lack of approach motivation (Davidson et al., 1994) or as a coping mechanism for dealing with stress (Gunnar, 1994). Each of these indices of “fear” may have unique associations with physiology and risk for anxiety symptoms (Buss, Davidson, Kalin, & Goldsmith, 2004; Davidson, Jackson, & Kalin, 2000). When studies use different measures to assess fear, inconsistencies in the literature are difficult to interpret. Because of this, we cannot assume that any two groups of temperamentally fearful children – for example, one identified based on distress behaviors and the other identified by avoidance behaviors are – homogeneous.

One approach to solving this problem is to observe children across multiple contexts, use multiple behavioral indicators of fear, and aggregate across situations to identify groups. For example, a hallmark of identification of behavioral inhibition is the consistency of children’s anxious or shy behavior across multiple contexts. However, behavioral indicators of inhibition sometimes vary widely, even within the same study, resulting in a low average inter-episode correlation (r = .27; Garcia-Coll et al., 1984). This low average correlation among situations designed to elicit the same types of behaviors has also been observed in our work, both across episodes (r = .18) and among multiple behavioral indicators of fear within the same episode (mean r = .14; Buss et al., 2004). Of note in this study, the toddlers identified as showing the highest levels of fear in each situation were not necessarily the same children (< 1/3 overlap among groups across episodes). These findings suggest that simply averaging behavior across multiple situations does not fully capture the complexity of fear, obscures meaningful individual differences, and leads to heterogeneity in the identification of fearful children.

Emotion Regulation and Role of Eliciting Context

The regulation of fearful behavior is also an important factor in the characterization of risk. Emotion regulation has been linked to both typical and atypical development (Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004), and the importance of emotion regulation has been demonstrated consistently across a broad range of studies. Regulatory processes are believed to be the organizing feature of affect systems and are predictive of developmental outcomes such as peer interactions and psychological adjustment. It has been argued that research on emotion regulation will be informed by studying behavior both in and out of context (Buss et al., 2004; Cole et al., 2004; Goldsmith & Davidson, 2004). Regulation is not just the process involved in reducing emotional intensity but it also involves the process of matching emotions to contextual demands placed on the individual, which leads to characteristic styles of regulating (or patterns of dysregulation) as part of one’s personality (Cole, Michel, & O’Donnell Teti, 1994). Examining the role of the eliciting context on fear behavior may help in the prediction of which children are most at risk for the development of anxious symptoms. In other words, what is important is the ability to regulate emotional reactivity in a manner that will facilitate appropriate interaction with the environment. When children develop a rigid pattern of behavioral reactivity (e.g., avoid any new situation), they will miss out on opportunities for experiencing new things such as learning new skills or information, and meeting new friends. Thus, children’s inability to change or modulate their behavior in different contexts is a key component of risk (Cole & Hall, 2008). This idea is consistent with identification of disorder in the DSM-IV where dysregulation (e.g., emotional distress beyond what is expected from the eliciting context or once removed from proximal elicitor) is a defining feature of anxiety disorders.

I predict that one key component of successful regulation will be children’s ability to match their behavior to the eliciting context. Thus, it is not how much fear is expressed, but when and how the fear is expressed that is most important for characterizing adaptive behavior. Failure to appropriately calibrate behavior to specific contexts, or to rigidly apply the same behavior to all types of situations, would constitute one type of dysregulation which may have important consequences for adjustment. This type of dysregulation would be observed as rigid stability in the behavioral profile across tasks. For instance, children who develop an emotion regulation strategy of withdrawal from novel contexts like playing with a new toy may also develop social withdrawal with peers (Thompson & Calkins, 1996), which has been linked to risk for social anxiety. Thus, emotion regulation as conceptualized here does not refer specifically to strategies that down-regulate negative emotions (Buss & Goldsmith, 1998) but instead is represented by patterns of behavior across situations.

Under this model of regulation, fear behavior outside the novel or threatening context is of particular interest for the development of maladaptive behavior patterns. Recent observations of inhibited children in non-threatening laboratory contexts speak to the conceptual framework of the current study. Inhibited children showed less impulsivity, less exuberance, and more sadness than uninhibited children across several laboratory situations (Pfeifer et al., 2002). This work is consistent with a number of persuasive studies of context effects on fear behavior in primates (Kalin, 1993; Kalin, Larson, Shelton, & Davidson, 1998; Kalin, Shelton, & Takahashi, 1991). These studies highlight how small changes in context can result in meaningful behavioral differences. In a previous study of 24-month-old infants, my colleagues and I demonstrated that small changes in the context of a stranger approach had dramatic changes on fear behaviors in toddlers (Buss et al., 2004). For most children the stranger approach in a free play context was the least threatening – as measured by amount of fear behaviors (e.g., freezing) observed. However, there were still a number of children who displayed long durations of freezing in this low threat context where coping resources, like seeking proximity to the parent, were readily available. Basal cortisol levels were highest, and resting PEP was shortest for these children. Thus, freezing behaviors in the low threat context were less adaptive (i.e., illustrated a failure to take advantage of coping resources) and reflected the dysregulation of fear behavior. Specifically, these persistent fear behaviors represented the failure to calibrate fear to contexts that varied in their level of threat. The current study is designed to replicate and extend these findings by expanding the number of type of contexts and observing children longitudinally.

Current Study

The previous review highlights a model of individual differences in temperamental fearfulness, the role of eliciting context, and how children regulate fear across various situations as an early precursor to risk for developing anxious behaviors. Using a prospective design, the current study examined the hypothesis that being fearful in situations that are relatively low in threat at age 2 would be an early indicator of risk for elevations in anxious behaviors across the preschool years.

There were three goals:

The first goal was to examine contextual differences in the expression of fearful behaviors. Which contexts were most threatening as indexed by the average amount of fear and avoidance elicited and the number of toddlers who were fearful during each episode? I hypothesized that the variation in level of threat would be associated with differences in observed fear and approach such that lowest threat episodes would elicit the least amount of fear and the most approach/engagement. In other words, most toddlers would find these episodes enjoyable and not be significantly wary. For the highest threat episodes, in contrast, most toddlers would engage in avoidance and be less likely to approach. Once the ordering of episodes from least to most threatening was established, the second goal was to characterize individual differences in patterns of fear across the contexts (e.g., high in fear in low threat, high in fear only in threatening tasks, or consistently high in fear). The consistency of fear behavior across these levels and types of contexts was expected to be low, suggesting that characterization of children high in fear would depend on a pattern of behavior across contexts. Specifically, a pattern of fear characterized by high fear in low threat contexts would be considered dysregulated. The third goal was to examine the link between dysregulated patterns of fear at age 2 and the relative risk for adult-reported anxious behaviors in preschool and the fall of the kindergarten year. It was hypothesized that toddlers who showed a dysregulated pattern of fear behavior across contexts would be more likely to have elevated anxious behaviors and be reported to have adjustment problems at the transition to kindergarten, specifically social withdrawal/avoidance. Given the heterogeneity in the methods used in the identification of fearful temperament in prior research, the relative contributions of both the dysregulated fear profile and other types of fearful behavior will be examined. I expected the dysregulated fear profile to predict anxious behaviors over and above other measures of temperamental fear.

Method

Participants

Participants were 111, 2-year-old toddlers (M age 24.05 months; range 18–30 months; 55% male)1 and the primary caregiver (typically the mother, hereafter referred to as mothers) drawn from a small Midwestern city and surrounding rural county using newspaper published birth announcements. The sample was largely middle-class (M Hollingshead index = 48.84; SD = 10.55; range 17–66, which was slightly higher than county average) and predominantly non-Hispanic and Caucasian (90.1% Caucasian, non-Hispanic, 3.6% African-American, 3.6% Hispanic, 1.8% Asian-American, .09% Indian-American), which largely mirrored the entire community (86% Caucasian, 8% African American, 2% Asian, 2% Hispanic, 2% mixed race, 1% other). Participating families were composed primarily of married parents (< 2% divorced or single parent families). At the kindergarten follow-up, the rates of divorce and single parent families increased to 6%.

At the age 3 and age 4 follow-ups, we obtained complete data on 69 and 65 families, respectively. Overall this represented follow-up of 95 total families (86%) during the preschool years (either at age 3 or 4, or both). Approximately 1 month prior to the beginning of formal schooling (i.e., kindergarten entry), families were invited to participate in a series of assessments as part of a larger ongoing study of children’s development. Only data from fall mother- and teacher-reported questionnaire packets from the kindergarten year will be presented in the current study analyses. We obtained data for the fall assessment from 85 families (77% of original sample, 89% of families who participated in one or both of the preschool assessments). Of these 85 families, there were 5 children who were homeschooled and we collected teacher data for 55 children (65%).2

Procedures

Eligible participants were mailed letters describing the study and asking them to return postcards if interested in participating. Upon receipt of postcards, we contacted mothers via phone to describe the study, confirm birth date and sex of child, obtain verbal consent, and schedule families for a laboratory visit. Mothers were mailed a questionnaire packet which contained the written consent form and brought the completed packet to their visit.

At the beginning of the laboratory visit, the packets were collected. Mothers were with their toddlers throughout the visit. Episodes used in the study were drawn and modified from the toddler and preschool versions of the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery, Lab-TAB (Buss & Goldsmith, 2000; Goldsmith, Reilly, Lemery, Longley, & Prescott, 1994) and other commonly used laboratory procedures. Because of specific hypotheses about the role of eliciting context on withdrawal behavior, toddlers participated in the episodes in 1 of 4 partially counterbalanced episode orders. Varying the order of episodes would not be necessary if the main interest was in individual differences and not potential differences across those episodes. However, the first goal of the study was to establish the validity of each context for eliciting fear/wariness versus approach/exuberance. Participants were randomly assigned to each episode order with the restriction that an equivalent number of males and females were assigned to each. There were 12 episodes in total, 7 of which were designed to be mildly to moderately threatening and would elicit withdrawal behaviors (described in detail in the next section). The other 5 episodes were designed to elicit positive emotions or were neutral in affective incentives3 and are not considered further in the current study. Episode orders were created so that two negative emotion-eliciting events never occurred back to back. For all episodes, mothers were instructed to sit in a chair, read a magazine and remain uninvolved unless their toddler became upset and needed their assistance.

At age 3 (36 months) and age 4 (48 months) families were contacted again to complete questionnaire packets containing follow-up assessments of temperament and behavior problem symptoms. Because of the interest in the transition to kindergarten, in the fall of the kindergarten year, mothers completed another set of follow-up questionnaires and gave consent to contact their child’s kindergarten teacher. Teachers were contacted via letter and follow-up phone calls. The teachers verbally consented over the phone and were mailed a packet containing a consent form and the questionnaire.

Age 2 Episode Descriptions

The first episode for every toddler was Risk Room, which is an episode commonly used to assess behavioral inhibition (Garcia-Coll et al., 1984; Goldsmith et al., 1994). Toddlers were brought into a large room containing several objects/toys and told they could play “however they would like.” The room contained a trampoline, a long, opaque tunnel, a balance beam, a black box constructed and painted to look like a monster, and a gorilla mask on a pedestal. After playing in the room for 3 minutes the experimenter returned and asked the toddler to play with each of the 5 objects in the room. For instance, she would say, “show me how you crawl through the tunnel.” This request was made a maximum of three times with approximately 20 seconds for the child to respond or comply. If the child did not comply the experimenter would move on to the next object.

Puppet Show and Clown were designed to be novel, yet engaging episodes in which two friendly puppets or a female clown invites the toddler to come play with them. These episodes were modified from procedures used in previous studies examining individual differences in approach and withdrawal in response to novelty (Nachmias, Gunnar, Mangelsdorf, Parritz, & Buss, 1996). Toddlers began these episodes seated in their mothers’ laps and were invited to participate. Both episodes lasted approximately 3 minutes and involved an unfamiliar female assistant (i.e., not the experimenter). In Puppet Show, the toddler and mom entered the room and sat on a chair opposite a puppet theater that was positioned approximately 10 feet away. The puppets – a lion and elephant – played together with balls and a fishing pole and continually invited the toddler to play with them. Each play epoch lasted 1 minute, followed by the puppets presenting the toddler with a sticker as a prize for playing/watching them. The puppets said goodbye and the research assistant came out from behind the theater, introduced herself and asked if the child would like to play with the puppets. The Clown episode followed a similar structure. After the child and mother were alone in the room for 10 seconds a female clown – wearing a clown outfit with wig and nose, but no make-up – entered the room, introduced herself as Floppy the Clown, and proceeded to rummage through a big bag to find toys to play with, periodically asking the child to join her. For 1 minute each, the clown played with big beach balls, bubbles, and musical instruments. After the first 2 minutes the clown remarked that it was hot in the room and removed her wig and nose. After 3 minutes the clown asked for help cleaning up her toys and left the room.

There were also two stranger episodes. In both episodes, the child started the episode on the floor with a few toys (a ball, a dump truck, and a Winnie the Pooh doll). In Stranger Approach, a male research assistant entered the room after approximately 20 seconds, introduced himself, and attempted to engage the child in conversation (e.g., “what’s your name, are you having fun playing here today?”). During the conversation, he also made his way closer and sat down within 2 feet of the child. If the child moved, the stranger stayed where he originally stopped and just turned around, if needed, to face the child. The conversation lasted approximately 1 minute, after which the stranger stood and said, “I just wanted to come and see the fun toys you have to play with. Thanks for sharing with me. Goodbye!” before he left the room. In the Stranger Working episode a female research assistant entered the room holding a clipboard, sat at a desk in the corner, and pretended to “work.” The stranger only spoke to the child if the child approached her, or initiated interaction (e.g., “I’m just going to work here while you play.”). She remained in the room for 2 minutes and then left saying, “Thanks for letting me work in here.”

The remaining two episodes were designed to examine effects of novelty, and object-related fear. At the beginning of both episodes the toddler was seated in the mother’s lap and was allowed to move about the room once the episode began. The Robot episode was modified from procedures used in previous studies of fear and novelty (Nachmias et al., 1996). The toddler and mother sat in a chair facing a platform containing a robot (~10 in. high). After a brief inactive period, the robot, controlled by an experimenter in the next room, began moving around the platform making noises and lighting up. The robot was active for 1 minute and then stopped. The experimenter entered the room and asked the child if s/he would like to come up and touch the robot. This request was made up to three times before the experimenter said, “It’s just a funny toy Robot.” The Spider episode, from the Lab-TAB procedure, was similar to the robot. Again the toddler and mother sat in a chair opposite a remote controlled spider which was a fuzzy toy spider mounted on a remote controlled vehicle. After a brief period of inactivity, the spider moved slowly toward the chair, stopping at the midpoint and then retreated. On the second approach the spider moved the entire distance across the room, paused and then retreated. The episode lasted approximately 1 minute before the experimenter entered and asked the child if s/he wanted to come and touch the spider.

Behavioral Scoring

With the exception of Risk Room, behaviors in each episode were scored using a second-by-second, micro-coding system. Child behaviors were scored to allow for the assessment of several parameters of emotional and behavioral expression: latency, intensity, and duration. Facial emotion expressions of were scored using the AFFEX (Izard, Dougherty, & Hembree, 1983) system which differentiates among various discrete facial expressions (e.g., fear, sadness, anger, and pleasure) based on three regions of the face. Given the goals of the current study, facial fear and facial sadness were examined. Facial fear was indicated by the brows being straight or normal but slightly raised and drawn together, the eyelids being raised or tense, and/or an open mouth with corners pulled straight back. Facial sadness was indicated by the inner corners of the brows being raised and outer corners being lowered, the eyes being narrowed or squinted, the cheeks being raised, and/or the corners of the mouth being pulled down and out, often resulting in the upper lip protruding at the center.

The presence and duration of bodily expressions of fear and sadness were also scored. Bodily fear included behaviors such as diminished play and freezing. Bodily sadness included behaviors such as head bowing and shoulder slumping. Duration of crying was also scored Approach and withdrawal behaviors in relation to the stimuli were scored and reflected the speed and distance covered in either approaching and touching the stimuli or withdrawing at maximal distance away. Duration of freezing was coded continuously when the child became still or rigid in response to stimuli for more than 2 seconds. For example, limbs may appear stiff and lifeless or frozen in an awkward position and often the only movement visible was breathing. Care was taken to not mistake freezing for a natural orienting response to change in stimulus activity, which typically only lasts for a couple of seconds (e.g., child stops activity briefly to attend to something novel but then resumes the activity). Proximity to mother and stimuli was scored to indicated whether the child was within 1 arms length from stimuli (or, in the case of proximity to mother, seated in her lap or touching her). Contact seeking to mother was coded when toddlers attempted to seek physical comfort from mothers, including reaching up to be held, climbing up on mother’s lap and clinging/resisting separation from mother. This behavior was only scored when the child actively sought to increase contact and did not include behaviors such as sitting quietly on mother’s lap.

During training coders were required to reach a minimum training reliability of 90% inter-rater agreement and a kappa (κ) .65 on each behavior. Because coding for this study used second-by-second ratings of each behavior, most coding epochs (i.e., each second) resulted in no observable behavior (i.e., scores of zero) and unbalanced marginal totals resulting in artificially low κ (Lantz & Nebenzahl, 1996). Therefore, inter-coder reliability was calculated as percent agreement on 15% of cases for each episode and reported here as the range of agreement across the behaviors used in the composites: Spider, 81 – 91%; Robot, 80 – 92%; Stranger Approach, 86 – 92%; Stranger Working, 81–100%; Puppet Show, 86–91%; and Clown, 86 – 89%.

Because the first goal of the study was to identify the typical amount of fear and withdrawal elicited by each episode rather than the intensity, I examined the prevalence of relevant behaviors across time (i.e., duration) and how quickly children engaged in those behaviors (i.e., latency). In order to identify a single behavioral component that would be operationalized as fearful or wary behaviors, the following 14 behaviors were submitted to an exploratory principle component extraction with Varimax rotation (PCA): latency to freeze, cry, and approach; duration of facial fear, facial sadness, bodily fear, freezing, bodily sadness, crying, approach, withdrawal, close proximity to mother and stimuli, and contact seeking. The same three component solution was identified for each episode. The following behaviors were identified as representing a Fear Component: latency to freeze (reverse scored), duration of facial fear, duration of bodily fear, duration of freezing, and duration of close proximity to mother. This component accounted for the most variance in all episodes, ranging from 22.42 – 29.57%. The following behaviors were identified as an Engagement Component: latency to approach (reversed), duration of withdrawal, duration of approach, and proximity to the stimulus. This component accounted for 14.03–16.57% of the variance. The following behaviors were identified as a Sadness Component: latency to cry (reversed), duration of facial sadness, duration of crying, and duration of bodily sadness. This component accounted for 10.28–13.10% of the variance. Contact seeking was the only behavior that did not load on any component so was not included in any composite. Using the solution from the PCA, behavioral composites for each episode were created by taking the mean of the behaviors for each component and adjusting for total length of episode within individuals to create a proportion score. Thus, for each episode a fear, an engagement, and a sadness composite was created, representing the proportion of time that type of behavior was observed. Cronbach’s alphas for the fear composite were good and ranged from (.61–.73) and were lower but acceptable for the engagement composite (.48–.54). There was moderate to large skew in the sadness composites and alphas were low (.32–.48) for all of the episodes (due to low occurrence of these behaviors) so were not considered further in the analyses. The fear and engagement composites were moderately correlated, as expected, within each episode (r’s = −.35 to −.62).

Composite Inhibition/Shyness Measure

A composite of toddlers’ general amount of inhibition and shyness across the visit was also created. Scoring from the Risk Room and a measure of shyness/hesitancy in Stranger Approach, Robot, and Spider was used in this composite. Risk Room scoring followed traditional Lab-TAB scoring procedures. The following behaviors were scored in the first portion of the episode when the child was free to play with the toys on their own: the latency to touch first, second, and third object, total number of objects touched (reversed), and total time spent playing with each object (reversed in composite). In addition, tentativeness of play was scored every 10 seconds on a 4 point scale (0 = no tentativeness; 1 = mild/brief hesitation to engage in play; 2 = moderate hesitation/tentativeness, not engaged a significant portion of time; 3 = maximum tentativeness, child is not engaged in play). This score was an average across the entire episode. Approximately 15% of tapes were double scored to calculate reliability on these variables. Reliability for tentativeness of play was good with percent agreement at 82% and κ = .76. The reliability for the timing variables was calculated as ICC; they ranged from .79 to .99 for latencies to touch the first three objects and .84 for number of objects touched. Correlations among these variables ranged from .21 – .83 (M r = .47). A composite of these 6 behaviors was created by standardizing and taking the average (α = .64).

Shyness/hesitancy was scored during the Stranger Approach, Robot and Spider episodes on a 5-point scale (one score per episode). The lowest score on this scale represented no shyness, hesitancy or withdrawal from stimuli and the highest score represented the highest level of shyness, hesitancy or withdrawal from the stimuli (e.g., leaving the room). If the episode was terminated early due to distress a score of 5 was automatically given. ICCs were calculated to measure inter-coder reliability on 20% of the cases and ranged from .80 to .89.

A composite of the risk room and shyness/hesitance variables was calculated by standardizing the four scores and taking the average (α = .70). This composite is referred to as inhibition.

Child Behavior Problem Measures

Given the specific hypotheses about risk for internalizing behaviors, and anxiety in particular, at each assessment phase we used age-appropriate maternal-report of behaviors. At ages 2 and 3, mothers completed the Infant Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA; Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones, & Little, 2003). The ITSEA is a 166-item parent report measure of social-emotional and behavioral problems and competencies in 12- to 36-month-olds, rated on a 3 point scale; (0) “Not true/rarely”, (1) “Somewhat true/sometimes”, and (2) “Very true/often” and scale scores were calculated as averages. For the current study, I examined only the internalizing composite which included a total of 30 items made up of individual scales of general anxiety (10 items), separation anxiety (6 items), depression/withdrawal (9 items), and inhibition to novelty (5 items). Given particular hypotheses about risk for anxiety the subscale of general anxiety was examined. Published alphas for the internalizing scales range from .71 – .80, with good test-retest reliability (ICC = .83), and criterion validity with other similar instruments (e.g., r = .57 with CBCL). In the current sample, the scale reliabilities were good with internalizing dimension α = .79 and .87 for age 2 and age 3, respectively. The general anxiety subscale reliabilities were also good, α = .65 and .71 for age 2 and age 3, respectively.

At the age 4 assessment mothers completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL 1 ½ to 5 version) (Achenbach & Ruffle, 2000) consisting of 120 items tapping behavior or emotional problems during the past 6 months. Mothers responded to each item with a score of (0) “Not true,” (1) “Somewhat true/sometimes,” or (2) “Very true/often true.” Scores for each scale were calculated as sums. Again the primary interest was in internalizing and anxiety, more specifically. In the technical publication the internal consistencies for these scales range from α = .66–.89. The internalizing dimensi on consists of 32 items including 5 items characteristic of anxiety. Cronbach’s alphas for the current sample were good for the internalizing dimension = .87, but somewhat low for anxiety scale α = .58. However, given specific hypotheses about anxiety this subscale was still examined.

At the fall kindergarten assessment, mothers and teachers completed the MacArthur Health Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ, (Armstrong & Goldstein, 2003; Essex et al., 2002). The HBQ measures dimensions of functioning such as mental and physical health, and social and academic competence. The HBQ consists of 172 items rated on a 3-point scale (0 = “rarely applies”, 1 = “somewhat applies”, or 2 = “certainly applies”) about the past six months. Published internal consistency estimates for the instrument scales range from .65 – .81 with test-retest reliabilities ranging from .68–.78. For the current study, we used the internalizing scale with a total of 29 items, including subscales of depression (7 items; e.g., “cries a lot”), overanxiousness (12 items; e.g., “worries about things in the future” and “nervous, high strung, or tense”), and separation anxiety – filled out only by mothers - (10 items; e.g., “avoids being alone” and “worries about being separated from loved ones”). Due to specific hypotheses about social wariness in the study, we also examined the scale of Social Withdrawal (9 items) which encompasses the asocial with peers (6 items; e.g., “prefers to play alone”) and social inhibition (3 items; e.g., “is shy with other children”) subscales. Scale scores were calculated as averaged scores from each item. For the current sample, the mother-reported sub-scale alphas were all good ranging from .71 – .83 (with the exception of depression α = .52, but this sub-scale was not examined in isolation in the analyses) and the internalizing dimension alpha was α = .83. For teacher report, the sub-scale alphas were all good ranging from .71–.85, with the internalizing dimension α = .85.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Analysis of Attrition and Missing Data

Current guidelines in the literature suggest that basing longitudinal analyses on only the subset of the sample who completes the later assessment (i.e., using listwise deletion) may bias parameter estimates and unnecessarily limit power, and that when the amount of attrition is at least moderate, imputation methods ought to be used (Howell, 2007; McCartney, Burchinal, & Bub, 2006). Over the course of three years, 26 families were lost to attrition. Comparison of age 2 study variables (i.e., SES, laboratory fear behavior and maternal report) for families who completed the study assessments and those who dropped out revealed no significant differences on any variable. To provide a more stringent test, the Missing Value Analysis in SPSS was applied to the data from all four assessments revealing a non-significant Little’s MCAR test chi-square = 1244.97, df, 1420, p = 1.0. This indicated that data were most likely missing at random. Therefore, we used the expectation/maximization likelihood treatment of missing data (i.e., the EM algorithm) to impute missing data for the age 3, age 4, and kindergarten assessments as per current recommendations in the literature (Howell, 2007).

Effects of Gender and Episode Order

There were no significant gender differences for observed behavior during the laboratory observation and only 1 significant correlation between gender and mother reported anxiety worry at age 2 (r = −.26, p < .05) with girls scoring higher than boys on this scale. Given that the number of significant associations was well below chance, gender was not considered as a covariate in subsequent analyses. Recall that episodes were presented to children in 4 different orders. We examined whether order, as a grouping variable, was associated with differences in the fear and engagement for each episode. Out of a total of 12 possible ANOVA analyses, there was only 1 significant difference such that engagement during Stranger Approach was lower in one of the episode orders compared to the other order groups. In Bonferroni corrected paired comparison post-hoc tests the differences were not statistically significant. Thus, episode order was not considered in further analyses.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate relations

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for the fear and engagement composites and internalizing scores are presented in Table 1. Given the specific focus on risk for anxious behaviors, specific anxiety-related scales were also examined. These means for these scales were: general anxiety at age 2 (M = .32, SD = .26); age 3 ITSEA General Anxiety (M = .30, SD = .24); age 4 CBCL Anxiety (M = 1.42, SD = 1.74); kindergarten mother HBQ Overanxiousness (M = .41, SD = .24) and Social Withdrawal (M = .56, SD = .32); and kindergarten teacher HBQ Overanxiousness (M = .41, SD = .36) and Social Withdrawal (M = .37, SD = .31). The magnitudes of the correlations among these scales across age were consistent with those presented in Table 1 for the internalizing domain scores, ranging from .27 to .55. Concordance between mother and teacher reports of these scales was modest: Overanxiousness, r = .28, and Social Withdrawal, r = .23.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations Among Episode-Specific Variables and Internalizing Behaviors

| Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear | Engage | ||||||||||||

| 1. Puppet | 29.96 (24.50) | 34.30 (15.81) | −.62 | .46 | .05 | .29 | .30 | .34 | −.22 | −.20 | −.31 | −.07 | .06 |

| 2. Clown | 17.02 (20.34) | 20.49 (7.86) | .36 | −.57 | .17 | .19 | .07 | .11 | −.26 | −.28 | −.12 | −.03 | −.02 |

| 3. Stranger A. | 21.81 (19.09) | 10.51 (10.56) | .16 | .29 | −.11 | .13 | .22 | .11 | −.19 | −.15 | −.22 | −.07 | .07 |

| 4. Stranger W. | 20.27 (14.78) | 13.46 (11.57) | .21 | .22 | .14 | −.43 | .11 | .17 | .06 | −.01 | −.09 | .07 | .24 |

| 5. Robot | 39.94 (19.60) | 16.62 (12.39) | .37 | .09 | .06 | .26 | −.29 | .38 | −.03 | .06 | −.00 | .23 | .14 |

| 6. Spider | 35.65 (15.26) | 10.71 (11.44) | .22 | .02 | .06 | .09 | .31 | −.35 | .06 | .06 | −.02 | .07 | −.06 |

| 7. Age 2 Internalizing | .42 (.18) | .14 | .34 | .27 | .08 | −.02 | .12 | 1.00 | |||||

| 8. Age 3 Internalizing | .38 (.21) | .13 | .37 | .31 | .03 | −.09 | .11 | .65 | 1.00 | ||||

| 9. Age 4 Internalizing | .17 (.16) | .33 | .20 | .25 | −.06 | .02 | .14 | .44 | .40 | 1.00 | |||

| 10. K. Internalizing (MR) | .30 (.18) | .07 | −.04 | .23 | −.13 | −.09 | .19 | .40 | .50 | .44 | 1.00 | ||

| 11. K. Internalizing (TR) | .29 (.25) | −.20 | −.01 | .01 | −.13 | .05 | .05 | .08 | .29 | −.03 | .20 | 1.00 | |

Note. Values below the diagonal represent correlations between the fear composites and values above the diagonal represent correlations between the engagement composites. Values highlighted in gray represent the correlations between the fear and engagement composites within each episode.

Correlations in boldface indicate p < .05. Stranger A. = Stranger Approach, Stranger W. = Stranger Working, K = Kindergarten Fall Assessment, MR = Maternal Report, TR = Teacher Report.

Using published cutoffs for borderline to clinical range scores on these three instruments, the percentage of children meeting this criterion was calculated. Internalizing dimension and anxiety scale cutoffs were observed in 2.7% and 10%, respectively, of toddlers at age 2; and 4.5% and 6.3% at age 3 according to mother-reported ITSEA scores; 2.7% and 2.7% at age 4 according to mother-reported CBCL scores; 8.1% and 8.1% of kindergarteners as reported by the mother on the HBQ; and 7.2% and 12.6% of kindergarteners as reported by teachers on the HBQ.

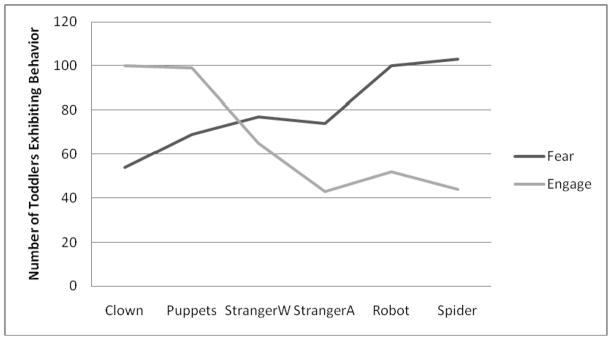

Differences among Episodes in Observed Fear and Engagement

Based on the incentive properties of the tasks, I hypothesized that variation in level of threat would be associated with differences in observed fear and engagement such that lower threat episodes would elicit the least amount of fear and the most engagement. In order to establish this ordering, I examined how much fear/engagement was elicited (average amount of fear/engagement) and for how many children was fear/engagement observed. For the count variable, I used a fairly liberal estimate of the presence of fear/engagement behavior (i.e., toddlers who displayed targeted behavior during more than 10% of the episode). Examination of the number of toddlers who displayed fearful and engagement behaviors across the 6 episodes confirmed this general pattern of increasing fear and decreasing approach as threat level of the task increased (Figure 1). Average levels of fear (presented in Table 1) are consistent with these findings with particular emphasis on the contrast between the lower and higher threat tasks.4 Based on these patterns, I argued that there are three levels of putative threat, and each level is comprised of two episodes. Low threat episodes included Clown and Puppet Show, moderate threat episodes included Stranger Approach and Stranger Working and the high threat included Robot and Spider.

Figure 1.

Number of Toddlers Displaying Fear and Engagement Behaviors Across the Episodes

Identification of High Fear Toddlers

Extreme groups by episode

The second goal of the study was to characterize individual patterns of fear behavior across the episodes. It was hypothesized that high fear in low threat would be one way to characterize dysregulated fear. Toddlers extreme in fearful behavior were identified for each episode as High Fear if they scored 1 SD above the mean on the fear composite. Using this method, we were able to identify 17 in Puppet Show, 17 in Clown, 21 in Stranger Approach, 17 in Stranger Working, 21 in Robot and 21 in the Spider episode. A reasonable question to ask would be whether these numbers represent the same toddlers. That is, if toddlers were classified as high in fear in one episode, were they also high in another? The comparison of the low threat to high threat episodes was most relevant to the specific hypotheses of this study. Fewer than 30% of toddlers who were high in Puppet Show were also high in either Robot or Spider; and fewer than 15% of toddlers who were high in Clown were also high in either Robot or Spider. Moreover, consistency in group membership across all episodes only occurred 20–25% of the time. Thus, there was low consistency in behavior across episodes demonstrating that toddlers who exhibit high fear in the lower threat contexts are a unique group of toddlers.

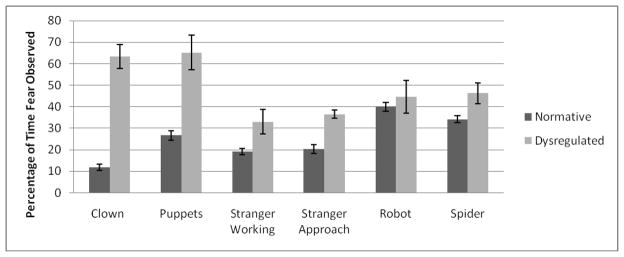

LPA across episodes

Another methodological approach to identifying individual differences in fearful behavior is latent profile analysis (LPA) which is a type of structural equation mixture modeling (SEMM) (Muthen, 2001). LPA is a statistical approach used to identify latent groups of participants based on patterns of observed behaviors across episodes by estimating the probability of profile membership and the profiles within the same model. Mplus version 5.1 was used to estimate the profiles. Two, three, and four-profile solutions were estimated and compared for model fit before the two-profile solution was selected. Examination of traditional fit statistics (i.e., lower BIC) and bootstrapping likelihood ratio tests (comparing each model to a hypothetical model with one fewer profiles to assess model fit) both showed that the two-profile solution was the best fit to this data (Figure 2). The normative profile (90% of sample) shows the hypothesized pattern of increasing fear from low to high threat. In contrast, the dysregulated fear profile (10%) was comprised of toddlers who had higher levels of fear in the lower threat episodes relative to the moderate to high threat episodes. In order to fully appreciate the differences between the LPA groups, I compared the groups on the observed behavior in each episode. With the exception of Robot, the dysregulated fear group had significantly higher fear proportion scores (t’s > −2.49). Moreover, in the two low threat episodes proportion of fear was more than doubled for dysregulated fear children; and the effect sizes for the low threat episodes were .23 and .58 for Puppet Show and Clown, respectively compared to an average effect size of .07 for the moderate-high threat episodes.

Figure 2.

Patterns of Fear Across Episodes for the Two Latent Profiles

Multilevel model analyses of fear regulation and dysregulation

Although identification of individual differences could proceed with GLM analyses within each episode from the extreme groups or LPA groups described above, this approach would significantly reduce power to detect effects. Thus, quantification of the pattern of change in fear across episodes would provide the opportunity to examine the entire sample. Given the repeated measures nature of the data (episodes nested in individuals), a multilevel modeling (MLM) approach was used instead (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). The nested data required a two-level model to create a continuous measure of fear across the six contexts, and used all 111 toddlers in the analyses.

First, I fit a model with no predictors and the fear composite only. An intraclass correlations coefficient (ICC; Snijders & Bosker, 1999) was computed for toddler fear behavior at the episode levels to measure the proportion of total variability accounted for by within-person similarity across observations. This model revealed that 14% of the variance between episodes was accounted for by individuals. In other words, toddler fear behavior was more similar for a single child across all the episodes than it was across all the children within a single episode. The non-zero values at this higher level indicated that observations of toddler distress behaviors across contexts were not independent, warranting the use of MLM. In contrast, for the engagement composite the ICC was only 7% suggesting that there was less variability across children in engagement.

Second, I dummy coded the episodes to form a threat-level contrast to be used as predictors in the models. Based on the results of the repeated-measures analyses three threat-level groups were formed: low threat (Puppet Show and Clown), moderate threat (Stranger Approach, Stranger Working), and high threat (Spider, Robot). This predictor was entered into the models for the fear and engagement composites to determine whether there were significant random components in the models. Significant random components would mean that the pattern of toddler behavior across contexts varies across individuals. In other words, random components would be necessary to argue for individual differences in behavior across episodes. Model fit improved when a random component for the fear composites was included, threat-level contrast indicated by significant deviance change tests (χ2 = 41.49, p < .001). While the deviance change test was also significant for the engagement composites, the variance of slopes estimates could not be estimated (i.e., set to zero). These results reveal significant variability across individuals in patterns of fear behavior across contexts. The same was not true for engagement behaviors, suggesting that for approach or surgent behavior the effects of the context (incentive properties) had a stronger influence on toddler behavior than individual characteristics. Since all episodes pulled for novelty this was not surprising. Therefore, remaining analyses tested only the fear composite.

In order to test the effects of context on fear behavior, we used the following multilevel model:

where the threat-level contrast reflected the low, moderate, and high threat episodes.

The random components were located within the error term. The coefficient attached to the context predictor (γ10) indicated the overall strength with which context predicted toddler behaviors across the sample. It can be interpreted like a slope in a regression model. Within this multilevel model, the threat context significantly related to corresponding toddler fear behaviors (γ = 14.11, t = 7.54, p < .001). This estimate indicates how much the change in context accounted for proportion of fear behavior observed. These estimates are the equivalent of a mean slope suggesting a linear increase in observed fear from low to high threat, for the threat context contrast.5 Thus the typical pattern of increasing fear as the episodes became more threatening reflects the adaptive regulation (or calibration) of fear behaviors across contexts from low to high threat. In contrast, a negative or flat slope would indicate lack of change in observed fear with changing contexts and thus represent a measure of dysregulation.

To address goals 2 and 3, we estimated a score for each individual’s slope for each threat-level contrast. Given the nested nature of the data, each toddler could be thought of as having their own regression equation with 6 (each episode) observations of fear behaviors. Just as the context coefficients (i.e., slopes) presented above reflected the overall pattern of change across context for the entire sample, this same coefficient in each individual’s regression could serve as a “score” or index of fear regulation. These individual coefficients were extracted as Empirical Bayesian (EB) estimates and added to the mean estimate. We have used this approach in our previous work (Kiel & Buss, 2006). Thus, we interpreted higher positive values as indicative of fear regulation (predicted increases in fear from low to high threat episodes) whereas low or negative slope values were indicative of fear dysregulation (i.e., higher fear in lower threat contexts relative to other toddlers). The mean intercept value was 20.85 and slope value was 14.11 (7.54) with a range from −.3.31 to 25.04. Thus, as threat increased one level, the average proportion of time children displayed fear increased by 14 units (e.g., a child who showed fear 20% of the time in the low threat contexts would show fear approximately 34% of the time in the moderate threat contexts, and 48% in high threat episodes). This pattern of increasing fear across threat level great than the mean was present in approximately 60% of sample, with 80% of the sample showing a slope of 10 or greater. Thus, the majority of toddlers were considered to be regulated in fear response across threat levels. There were 11 toddlers who had zero or negative slopes (< 1 SD below the mean, representing no change, or slight decreases in fear as threat increased. Note also that the correlation between intercept and slope was very high (r = −.80) suggesting that, as hypothesized, toddlers displaying high fear in low threat were more likely to have negative or flat slopes. Finally, there were no children with a flat slope score who were characterized by low in fear across episodes.

Overlap in three approaches to identifying fearful toddlers

Because I hypothesized that identification of the fear dysregulated toddlers would best be characterized as high fear in low threat, a direct test of the overlap in group membership across the three methods is warranted to demonstrate that the same toddlers were identified as high in fear in each approach. Thus, I compared the three methods of identifying high fear toddlers: (1) extreme groups from the low threat episodes, Puppet Show and Clown; (2) LPA groups; and (3) Toddlers scoring 1 SD below the mean on the slope measure. Overlap among the different high fear classifications was very high. Of the 11 toddlers with slopes less than 1 SD below mean (i.e., dysregulated slopes) 9 were also characterized as high in fear to the Puppet Show and Clown episodes (82% overlap). Of the 10 children characterized as dysregulated in the LPA analysis, all 10 were high in fear to Puppet Show and Clown as would be expected from examination of Figure 2 and 8 had slope 1 SD below the mean (80% overlap).

Next, in order to explore the hypothesized association between high fear in low threat episodes and anxiety at age 5, comparisons between each extreme group classification were made using analysis of variance. Anxiety at age 2 was entered as a covariate in these models. Results are presented in Table 2. As expected, high fear in low threat episodes was associated with high anxiety scores at age 5. Toddlers in the high fear groups for Puppet Show, Clown, and the dysregulated fear profile group were more likely to have elevated anxiety scores compared to the low fear groups. The mean difference between the high fear and low fear groups for Robot did not remain significant after controlling for anxiety at age 2. Thus, as expected toddlers who were high in fear in the lower threat episodes were more likely to be reported by adults as anxious. This was not the case for toddler identified as high in fear to the higher threat episodes.

Table 2.

Extreme group comparisons in predicting maternal-reported anxiety.

| Group Type | Maternal Report Social Withdrawal | Teacher Report Overanxiousness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | F | ES | Low | High | F | ES | |

| M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | |||||

| Puppet Show | .42(.32) | .68(.34) | 4.45* | .13 | .26(.28) | .50(.35) | 5.77* | .13 |

| Clown | .48(.37) | .80(.48) | 6.86* | .14 | .32(.31) | .50(.37) | ns | - |

| Str Approach | .46(.35) | .59(.32) | ns | - | .38(.35) | .41(25) | ns | - |

| Str Working | .49(.32) | .50(.34) | ns | - | .48(.35) | .35(.34) | ns | - |

| Robot | .37(.27) | .60(.32) | ns | - | .43(.31) | .33(.28) | ns | - |

| Spider | .47(.38) | .58(.36) | ns | - | .39(.27) | .45(.33) | ns | - |

| LPA | .50(.29) | .95(.21) | 21.97* | .19 | .26(.22) | .42(.34) | ns | - |

Note. All tests at ages 3, 4 and 5 control for age 2 anxiety. Text in boldface are tests that were significant and in the predicted direction. For LPA test low = regulated/typical pattern and high = dysregulated pattern (see Figure 2). The effect size reported in this table is ε2

Bivariate Relations among Inhibition, Fear Regulation, and Reported Anxiety6

Although the pattern of results using the extreme groups was in the hypothesized direction, power was limited and in the case of the LPA there were unequal sample sizes. Thus, the fear regulation measure which represented the slope from low to high fear provided a means to use the continuous information from the entire sample and increase power. Table 3 presents the correlations between the MLM constructed fear regulation measure, the inhibition composite, and maternal- and teacher-reported internalizing dimension and specific anxiety scales. The inhibition composite and fear regulation slope were correlated (r = −.61) such that higher average inhibition/shyness across tasks was associated with a flatter/more negative slope. The negative correlations between fear regulation and the internalizing scales reflect an association between increasing internalizing scores for toddlers who have a flatter or negative slope, such that fearful behaviors did not change, or specifically increase as expected, across the episodes. In sum, failure to regulate fear across the episodes was associated with higher anxiety scores across the three follow-up ages. In addition, the average amount of inhibition/shyness across the episodes was also associated with social withdrawal as reported by mothers, but not by teachers.

Table 3.

Correlations between Adult-Reported Internalizing/Anxiety and the Fear Regulation Measure and Inhibition Composite

| Internalizing Scale | Age 2 | Age 3 | Age 4 | Age 5 | Age 2 | Age 3 | Age 4 | Age 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear Regulation | Inhibition | |||||||

| Mother-Reported | ||||||||

| Internalizing | −.30** | −.30** | −.31** | −.05 | .25** | .30** | .18 | .10 |

| Anxiety | −.32** | −.31** | −.35** | −.06 | .34*** | .11 | .30** | .05 |

| Social Withdrawal | -- | -- | -- | −.41** | -- | -- | -- | .38*** |

| Teacher-Reported | ||||||||

| Internalizing | -- | -- | -- | .13 | -- | -- | -- | −.04 |

| Anxiety | -- | -- | -- | −.19† | -- | -- | -- | −.07 |

| Social Withdrawal | -- | -- | -- | .02 | -- | -- | -- | .14 |

Note.

< .10

p < .05,

p < .01.,

p <.001. Age 5 is fall of kindergarten year.

Regressions Predicting Maternal-Reported Anxiety from Fear Regulation

A series of hierarchical regressions were conducted to test whether fear regulation predicted internalizing/anxious behavior outcomes over and above the inhibition composite. In addition, to protect against Type I error only regressions for the anxiety and social wariness subscales were performed. The inhibition composite was entered first followed by the fear regulation measure and their interaction. Given the pattern of correlations between the fear behavior measures and internalizing at age 2, the anxiety measure from age 2 was covaried in the first step for the longitudinal analyses.

The results of the regressions are presented in Table 4. Note that in all regressions the final model was the step that included the fear regulation measure; that is, none of the interaction terms were significant so they are not reported. For the age 2 concurrent model, the fear regulation measure emerged as the best predictor of maternal report of anxiety when it was entered into the model, F (2, 108) = 8.72, p < .001, R2 = .14). After controlling for age 2 anxiety and inhibition, fear regulation was related to age 3 maternal reported anxiety, F (3, 107) = 6.44, p < .001, R2 = .15). Note that inhibition was not a significant predictor in the age 3 models. At age 4, the pattern of results was identical to age 3, with only age 2 anxiety and fear regulation as significant predictors of maternal-reported anxiety, F (3, 107) = 10.10, p < .001, R2 = .22). The model for maternal-reported kindergarten social withdrawal revealed that only regulation predicted higher social withdrawal, F (3, 107) = 9.82, p < .001, R2 = .22). Finally, the model for teacher report revealed that age 2 anxiety and fear regulation significantly predicted overanxiousness, F (3, 107) = 2.88, p < .05, R2= .08. In these last two models of kindergarten anxiety, inhibition did not contribute significant variance to the final model. In sum, fear regulation emerged as a significant predictor over and above the effects of concurrent anxiety and general level of fear/inhibition.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Regressions predicting anxiety outcomes from observed fearful behavior at age 2.

| Models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔR2 | ΔF | β | t | |

| Outcome: Concurrent Anxiety | ||||

| Model 1 | .11 | 13.99*** | ||

| Inhibition | .34 | 3.74** | ||

| Model 2 | .03 | 3.56* | ||

| Inhibition | .21 | 1.88† | ||

| Fear Regulation | −.20 | −2.01* | ||

| Outcome: Age 3 Anxiety | ||||

| Model 1 | .12 | 15.30*** | ||

| Age 2 Anxiety | .34 | 3.91*** | ||

| Model 2 | .00 | .70 | ||

| Age 2 Anxiety | .35 | 3.68*** | ||

| Inhibition | .01 | .04 | ||

| Model 3 | .03 | 3.76† | ||

| Age 2 Anxiety | .38 | 4.00*** | ||

| Inhibition | .12 | 1.06 | ||

| Fear Regulation | −.22 | −1.94† | ||

| Outcome: Age 4 Anxiety | ||||

| Model 1 | ||||

| Age 2 Anxiety | .17 | 21.50*** | .41 | 4.64** |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Age 2 Anxiety | .35 | 3.76** | ||

| Inhibition | .03 | 3.89 | .18 | 1.97† |

| Model 3 | ||||

| Age 2 Anxiety | .32 | 3.43** | ||

| Inhibition | .06 | .56 | ||

| Fear Regulation | .03 | 3.71* | −.21 | −1.93† |

| Outcome: Kindergarten Social Withdrawal (Mother-Report) | ||||

| Model 1 | .08 | 9.85** | ||

| Age 2 Anxiety | .29 | 3.14** | ||

| Model 2 | .09 | 11.72*** | ||

| Age 2 Anxiety | .18 | 1.94† | ||

| Inhibition | .32 | 3.42** | ||

| Model 3 | .04 | 5.90** | ||

| Age 2 Anxiety | .14 | 1.54 | ||

| Inhibition | .17 | 1.52 | ||

| Fear Regulation | −.27 | −2.43* | ||

| Outcome: Kindergarten Anxiety (Teacher Report) | ||||

| Model 1 | .02 | 1.78 | ||

| Age 2 Anxiety | .13 | 1.33 | ||

| Model 2 | .01 | .00 | ||

| Age 2 Anxiety | .17 | 1.67† | ||

| Inhibition | −.12 | −1.21 | ||

| Model 3 | .05 | 5.25* | ||

| Age 2 Anxiety | .20 | 2.06* | ||

| Inhibition | .03 | .28 | ||

| Fear Regulation | −.27 | −2.29* | ||

Note.

< .10

p < .05,

p < .01.,

p <.001

Discussion

Which fearful toddlers should we worry about? Results supported the hypothesis that elevated anxious behaviors in preschool and kindergarten were predicted by a dysregulated fear profile characterized by high fear in low threat contexts at age 2, and that this was true over and above the effects of general level of fear or inhibition. This is the first study to identify dysregulated fear as a potential precursor to risk for anxiety behaviors. Specifically, these findings support the hypothesis that identification of early risk may benefit from an understanding of this extreme and putatively maladaptive behavioral profile - the mismatch between intensity of fear and the incentive property of the situation (e.g., the threat context). After briefly summarizing the results, discussion will turn toward the implications of this precursor to risk model.

Findings were consistent with our previous work, which has shown that the context-specificity of a fear response (e.g., higher fear reaction in a lower-threat situation) is associated with a more extreme physiological stress reactivity profile (Buss et al., 2004). In addition, fearful profiles have traditionally been characterized largely by the intensity of behaviors (e.g., inhibition, crying and facial fear), and these indices were not related to physiology. In this previous study, we pointed out that future research must examine a variety of contexts that vary in the type of threat, intensity of threat, and incentive properties. The current study was designed, in part, to meet this call.

The goals of the current study were threefold. First, threat episodes were ordered. Consistent with predictions, episodes could be characterized as low, moderate, and high in threat based on patterns of behaviors consistent with fear and engagement. The group data indicated that the type of situations toddlers found to be most fearful or those with which they were most engaged appeared to be influenced strongly by the incentive properties of the situation. From the pattern of correlations in Table 1, it was clear that the consistency of behavior across episodes was low to moderate, suggesting that for most children the context was influential in determining level of fear and engagement.

Second, individual patterns of fear behavior were identified. The extreme group approach revealed that the concordance between high fear status across the contexts was relatively low, which is consistent with the pattern of correlations and our previous work (Buss et al, 2004). The patterns of fear and engagement behavior were examined in a multi-level framework; and the slope of children’s fear response across contexts was used as an index of regulation or dysregulation relative to group norms. The mean fear slope estimate was positive, which reflected an increase in fearful behavior as the contexts became more threatening or novel. This is the pattern that was characterized as adaptive fear regulation (i.e., calibration of fear to the situation). Thus, toddlers with individual fear slope estimates that were positive were characterized as regulated in their fear response across all contexts. Individual fear slope estimates that were near zero (flat) or negative were characterized as dysregulated, because this indicated that fearful behavior was high even during the lower threat episodes – the episodes in which most children were low in fear and high in engagement. Thus, the most important component of the dysregulated pattern was the lack of change or flexibility in the fear response across contexts.

Third, using these individual estimates of regulation, we examined whether fear regulation predicted risk for anxious behaviors as reported by mothers (each year) and teachers (after beginning school) through the fall of the first year of school. As predicted, a dysregulated pattern of fear behavior across contexts was associated with higher maternal reported anxiety in preschool and social withdrawal in kindergarten. At the transition to kindergarten teachers reported higher anxiety for children whose toddler fear profile reflected dysregulation. Inhibition was unrelated to anxious behaviors concurrently and during the preschool assessments. During kindergarten inhibition was associated with maternal-reported anxiety, specifically social withdrawal but dysregulated fear still predicted variance in anxious behavior over and above inhibition.

Emotion Dysregulation as Risk

These findings speak to the putative mechanisms that place fearful children at risk for developing anxious behaviors. One possibility, as hypothesized in the current study, is that maladjustment is defined not by how much fear children show but how the level of fear experienced is commensurate with objective level of novelty and threat of a situation. A child who fits this profile likely perceives more situations as threatening, including situations in which other children are typically only slightly wary (or not at all). One way to characterize this pattern of behavior is as a failure to modulate or regulate fear across changing contexts.

The extant literature is rife with support for models of emotion regulation as a protective factor against the development of behavior problems (e.g., Cole et al., 1994). Specifically, the ability to effectively regulate negative emotions under conditions of stress is related to fewer behavior problems (Eisenberg et al., 1997; Gilliom, Shaw, Beck, Schonberg, & Lukon, 2002). While the bulk of these studies examined the “down” regulation of negative emotions, regulation is not a unitary construct and the pattern of behavior that constitutes adaptive regulation depends on several factors such as adaptability, flexibility, children’s goals (Cole & Hall, 2008) and the context of the situation (Goldsmith & Davidson, 2004). Goldsmith and Davidson argue that emotion dysregulation can be characterized by emotions that are disconnected from the incentive properties of the situation. They argue that “high fear under threatening incentives has a different meaning, and thus different correlates, than high fear in nonthreatening contexts.” Thus, the construct of emotion regulation is not synonymous with down-regulation of negative affect or measures that captures the reduction in expressed emotion in a given situation (e.g., discrete behaviors that lessen fear expression). Instead, the current study supports a broader definition of regulation which includes the effective calibration of one’s emotional responses to the situation at hand.

Why would fear in low threat episodes be considered dysregulated? Experience of distress can be modulated by the incentive properties of the situation: perception of threat, novelty, predictability, controllability, whether stimulus approaches or not, and availability of coping resources. Ability to recognize these properties and/or use the resources available results in regulation of fear across contexts – flexibility of fear response with the changing demands of the situation (i.e., regulated fear response). In contrast, a dysregulated fear response under these same changing contexts would be reflected by a mismatch between the incentive properties of the situation and the response. This mismatch would be most observable in low-threat situations. It is argued that this may constitute a maladaptive response because it represents a type of rigidity or inflexibility in response (reaction) across contexts. It is not the intensity of fear itself, then, that indicates a precursor to risk (e.g., fearful temperament) but this type of fear dysregulation. Results were consistent with this in that only the fear regulation measure, not fearful temperament, was associated with anxious and social wary behaviors 1, 2, and 3 years later.

Up to this point, the episodes have been discussed as contexts varying in level of threat based on incentive properties. There is, however, an alternate distinction among episodes that warrants discussion. Specifically, four of the episodes represented social challenges and two represented object-oriented threats. Moreover, in all but one of the social episodes the toddler received several bids for social interaction. Hesitancy and withdrawal (i.e., reticence) to these bids are consistent with mod els of social withdrawal (Rubin & Burgess, 2001; Rubin, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009) as a specific form of solitary behavior and replicate work showing links to development of anxious behaviors in these children (Rubin, Coplan, Fox, & Calkins, 1995). Given that social withdrawal in kindergarten emerged as a key outcome the salience of social situations to this type of fearful child needs further exploration. The current study was unable, however, to disentangle level of threat from the type of threat. That is, the high threat episodes were both object-oriented and non-social. It would be important for future research to identify situations that align in terms of type of threat but vary in intensity.

Finally, this study was not designed to determine why toddlers would be fearful to the low threat contexts. It could be that they are misinterpreting or over-interpreting the threat or attending to some component of the stimulus that increases their fear. For instance, in the puppet show the children with are wary may be attending more to the fact that there is a stranger behind the theater instead of the fun puppets and games. Thus, it could be that for this fearful group of toddlers there is a bias to attend to those properties of a situation that are most threatening. However, if this was the case then we might expect the children who show high fear in low threat to be highly fearful in all types of situations. This was not the case in the current study. Future work should examine whether an attention bias might account for the amount of fear expressed in putatively low threat situations. We have some recent data from my laboratory that supports this attention bias explanation. Attending to the gorilla mask in the Risk Room, arguably the most threatening stimulus in that situation predicted social inhibition (Kiel & Buss, in press). Specifically, when toddlers did not approach the mask, increased attention to the mask was associated with more inhibition.

Implications of Results for Understanding Trajectories of Risk for Anxiety