Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the prognostic value of a coronary artery calcium score (CACS) of 0 in patients with stable chest symptoms and to compare it as a first-line test with bicycle exercise testing (X-ECG). Altogether, 315 consecutive patients over 44 years of age, with stable chest symptoms and no previous diagnosis of coronary artery disease (CAD) visited the outpatient clinic of our community hospital and underwent both CACS and X-ECG. The mean age was 60.54 years (SD 9.7; range 45–88 years). Of these patients, 141 had no detectable coronary calcium (44.8%) We excluded patients who did not sign informed consent (n = 4). Three patients were lost to follow-up. The follow-up group therefore consisted of 134 patients. The mean follow-up period was 44.6 months (25th–75th percentile: 35.5–54.3 months), during which no major adverse cardiac events (MACE) occurred. The negative predictive value (NPV) was 100%. X-ECG was negative in only 89 patients, equivocal in 39 patients and false-positive in 6 patients requiring additional stress myocardial imaging in 45 patients. NPV as a first-line test was therefore 66.4%. In conclusion: patients over 44 years with stable chest symptoms and no detectable coronary calcium have an excellent prognosis. CACS performs better compared with X-ECG as an initial test in patients with stable chest symptoms.

Keywords: Coronary atherosclerosis, Stable coronary artery disease, Calcium score, Exercise testing

Introduction

Angina pectoris is chest discomfort due to myocardial ischaemia. In chronic stable angina symptoms are predictable and have been occurring over several weeks without major deterioration [1]. Patients diagnosed with stable angina have a 4–6% annual risk of a major adverse coronary event (MACE) and stable angina is the main cause of heart failure [2, 3]. Patients with no or mild symptoms and little ischaemia can safely be treated with medical treatment alone. Particularly in patients with extensive coronary artery disease (CAD) and documented moderate-to-severe ischaemia, revascularisation exerts favourable effects on symptoms, quality of life, exercise capacity, and survival [4].

General practitioners refer their patients with stable chest pain if the diagnosis is unclear or if anti-anginal drugs fail [5]. Since effective preventive medical therapy is available a definitive diagnosis is important [6, 7].

Guidelines recommend noninvasive stress testing to determine the need for cardiac catheterisation in patients at low or intermediate risk for obstructive CAD [1]. However, in routine clinical practice the diagnostic yield of cardiac catheterisation is low [8].

Exercise electrocardiography (X-ECG) is the test of choice in patients with stable chest symptoms and low to intermediate pretest likelihood of significant coronary artery disease, despite its relatively low sensitivity (67%) and specificity (72%) and the percentage of patients that cannot perform the test due to abnormal resting ECG or physical inability [9].

Calcification of atherosclerotic plaque occurs from the fourth decade of life [10]. Multidetector computed tomography accurately detects coronary artery calcium (CAC) [11]. Absence of CAC is associated with a very low likelihood of significant CAD [12].

Therefore, we postulate that if a symptomatic patient of 45 years and older with stable chest symptoms has no detectable calcium (CACS = 0), the patient has an excellent prognosis and coronary angiography can then be avoided.

The primary aim of this study was to assess the follow-up of symptomatic patients from the outpatient clinic of our community hospital with stable chest symptoms and no detectable calcium. The second aim was to compare the effectiveness of CACS and X-ECG as a first filter in the analysis of these patients.

Methods

Between November 2003 and March 2005, 385 consecutive patients over 44 years of age, with stable chest symptoms and no previous diagnosis of coronary artery disease, visited the outpatient clinic of our community hospital. A total of 70 patients were unable to exercise and were therefore excluded from this study. The remaining 315 patients underwent both CACS and X-ECG. The mean age was 60.5 years (SD 9.7; range 45–88 years); 141 patients had no detectable coronary calcium (44.8%). We excluded four patients who did not sign informed consent (n = 4) and three patients who where lost to follow-up (n = 3). The follow-up group therefore consisted of 134 patients. The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee.

On the basis of history, age and sex the pretest likelihood of CAD was assessed using table 4 of the ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing [9].

Patients were classified as current smoker, former smoker, or non-smoker. Diabetes was defined as a history of taking medication for diabetes, or HbA1c ≥ 6.5 or fasting plasma glucose >7 mmol/l or a random plasma glucose >11.1 mmol/l. A patient was considered to have a positive family history of CAD if a first-degree relative had a history of coronary artery disease or stroke before the age of 60 years. A patient was considered to be hypertensive if he received such a diagnosis on the basis of arterial blood pressure >140 or >90 mmHg or was being treated with antihypertensive medication. A patient was considered to have hyperlipidaemia if taking cholesterol-lowering medication or if the blood cholesterol levels were >6.0 mmol/l. Patients’ data on baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Parameter | CACS = 0 (n = 134) |

|---|---|

| Age, year (SD) | 57.3 (±8.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| - Women | 109 (81.3) |

| - Men | 25 (18.7) |

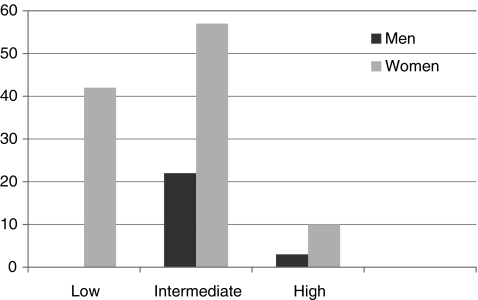

| Pretest likelihood, n (%) | |

| - Low | 42 (31.3) |

| - Intermediate | 79 (59.0) |

| - High | 13 (9.7) |

| Risk factors, n (%) | |

| - Hyperlipidaemia (%) | 41.8 |

| - Hypertension (%) | 32.8 |

| - Family history (%) | 51.5 |

| - Diabetes mellitus (%) | 11.9 |

| - Smoking (%) | |

| • Current | 18.7 |

| • Former | 29.9 |

| - BMI >30 | 11.2 |

CACS coronary artery calcium score, SD standard deviation, BMI body mass index

Exercise ECG

Bicycle X-ECG was performed by a standardised protocol with established criteria for performance and exercise discontinuation [9, 13]. Criteria for myocardial ischaemia included horizontal or down sloping ST-segment depression or ST-segment elevation >0.1 mV 80 ms after the end of the QRS complex or typical, increasing angina during exercise [9].

X-ECG results were classified into three groups: 1) normal exercise test with maximum exertion; 2) an abnormal test with significant ECG signs of ischaemia; 3) an equivocal test either due to inadequate exercise (heart rate <85% of predicted maximum), non-diagnostic ECG changes, medication not stopped, or resting STT changes.

Calcium score

A 16-row MDCT scanner (Sensation 16, Siemens, Germany) was used to acquire a volume set of data of the heart, according to a standard spiral protocol of the coronary arteries. Scans were made during maximal inspiration. Image reconstruction was performed by using retrospective ECG gating. The reconstruction parameters were 3-mm effective slice thickness, and 1.5-mm increment. To obtain motion-free images, standard reconstruction windows were selected during the mid- and end-diastolic phases (350, 400 and 450 ms before the next R wave). An ECG gated pulse technique was used for online dose modulation in patients with a regular heart rhythm. During systole the output of the tube was reduced, which may lead to a mean dose reduction of 47%. The effective radiation dose of this standard protocol before dose modulation was 2.1 mSv for men and 3.1 mSv for women. The calcium score was calculated using dedicated software (Calcium scoring, Wizard workstation, Sensation 16, Siemens, Erlangen). The CAC scores were measured according to the Agatston method [14].

Follow-up

Follow-up became available from the hospital records, the referring physician or by a questionnaire after written informed consent when the patient was discharged from the outpatient clinic. The primary endpoint was composite of death due to coronary heart disease, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and unstable angina requiring revascularisation.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation, and categorical baseline data were expressed in numbers and percentiles. Negative predictive values (NPV) were calculated for CACS and bicycle exercise test. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

The mean age of 134 patients without coronary calcification was 57.3 years (SD 8.7; range 45–81 years). Pretest likelihoods are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Number of patients with low, intermediate and high pretest likelihood

A mean follow-up time of 44.6 months (25th-75th percentile: 35.5–54.3 months) was obtained during which no MACE occurred. Therefore we were able to exclude significant CAD in 134 patients without detectable coronary calcium. The NPV for CACS as a first-line test was 100%.

X-ECG was negative in 89 patients, false-positive in 6 patients and equivocal in 39 patients. In conclusion the X-ECG was able to rule out significant coronary artery disease in 66.4% of patients, requiring additional stress myocardial imaging in 45 patients. NPV as a first-line test was therefore 66.4%.

Discussion

This study assessed the prognostic value of a CACS = 0 in patients over 44 years of age with stable chest symptoms for more then 6 weeks, across all pretest likelihoods for CAD. A CACS = 0 makes obstructive CAD very unlikely and is associated with an excellent prognosis [12, 15–17]. Also in our study no MACE occurred in this group. Since acute onset angina has a different aetiology as compared with stable angina [18] we only included the latter in this study.

The main result of this study shows that if symptomatic patients with stable chest symptoms have no detectable calcium their long-term prognosis is excellent. In this patient cohort of our outpatient clinic 44.8% of the patients with stable chest symptoms have no detectable calcium. Even patients with no detectable calcium in the high pretest likelihood subgroup in this study did not suffer MACE in follow-up, but care should be taken when interpreting these data because here numbers are small.

Because CACS can be performed in almost all patients, is noninvasive, no contrast agent is required and a substantial number of the symptomatic patients have no detectable coronary calcium this study has important clinical implications.

CACS performed better as a first filter then the X-ECG. Sehkri et al. [19] studied the incremental prognostic value of resting and X-ECG in the assessment of ambulatory patients and found only limited incremental value to basic clinical assessment.

The prevalence of no detectable calcium decreases with age, but even in the age group above 60 years, 14.2% of men and 36.4% of women in our study did not show any coronary calcium and therefore CACS can also be used as a first filter in this age group.

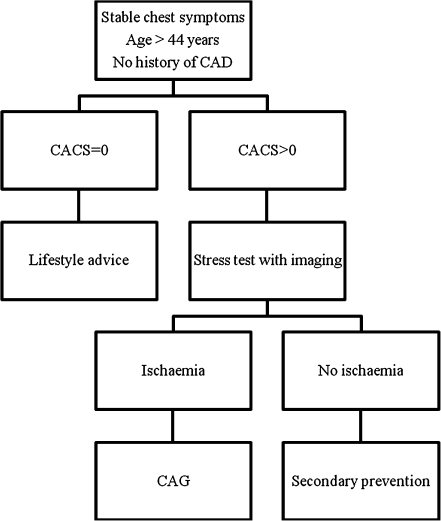

The result of CACS effectively further risk stratified the low, intermediate and high pretest subgroups into a group with CACS = 0 and an excellent prognosis and a mixed group with CACS > 0 in which further testing is necessary. Therefore we propose the algorithm shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Algorithm for the management of patients with stable chest symptoms. CAD coronary artery disease, CACS coronary calcium score CAG coronary artery angiography

The strength of this study is that it represents ‘daily life’ in a community hospital. We consider the high proportion of women in the present study especially to be a strength because women also comprise a high proportion in real-world chest pain populations [20]. This is interesting because the bicycle exercise test in women performs less well than in men [21, 22].

Previous diagnostic studies of CAC scoring in symptomatic patients are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Diagnostic studies of calcium scoring in symptomatic patients

| Author/year [ref.#] | Type | Population | Total patients | Male (%) | Included <45 years | Prevalence CACS = 0% | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarwar et al./2007 [12] | Review | Referred for CAG | 10,355 | – | + | 20 | 93 |

| Rubinshtein et al./2007 [23] | Retrospective | Referred for CTA; stable and unstable | 125 | 55 | + | 100 | 93 |

| Marwan et al./2008 [24] | Retrospective | Obstructive CAD; stable and unstable | 21 | 76 | + | 100 | – |

| Schenker et al./2008 [25] | Prospective | Referred for PET, stable and unstable | 695 | 40 | + | 34 | 84 |

| Kelly et al./2008 [26] | Retrospective | Asymptomatic/ symptomatic; referred for CTA | 729 | 68 | + | 45 | 96 |

| Akram et al./2009 [27] | Retrospective | Referred for CTA | 134 | 37 | + | 37 | 92 |

| Nieman et al./2009 [20] | Prospective | Stable chest pain | 471 | 52 | + | 37 | 98 |

| Gottlieb et al. /2010 [28] | Prospective | Referred for CAG; stable and unstable | 291 | 73 | + | 25 | 68 |

| Werkhoven et al/2010 [29] | Prospective | Referred for CTA; symptomatic, stable | 576 | 47 | + | 42 | 94 |

CACS coronary artery calcium score, NVP negative predictive value, CAG coronary angiography, CTA computed tomography coronary angiography, CAD coronary artery disease

Most studies have been limited by biased samples. If patients are referred for CAG it is likely that results are influenced by a selection bias towards high pretest probability of disease. Furthermore absence of CAC can only exclude significant CAD in a population where calcification can be present. Therefore in young patients a CACS = 0 does not rule out significant coronary disease. Also in patients with an unstable presentation absence of coronary calcium does not exclude the presence of unstable plaque. Marwan et al. [24] analysed the clinical characteristics of 21 patients with obstructive CAD in the absence of coronary calcification. Patients were younger (mean age 53, range 33–76) and more frequently presented with unstable symptoms (71%) as compared with patients with detectable calcium.

Gottlieb et al. [28] reported a study which was designed to evaluate whether the absence of coronary calcium could rule out ≥ 50% coronary stenosis or the need for revascularisation. The NPV was only 68%. In this study, patients with acute coronary syndrome were also included and emergency room admission was the only variable associated with CACS = 0 and obstructive CAD.

Sarwar et al. [12] recently reviewed the diagnostic and prognostic value of absence of coronary artery calcification. They concluded as suggested by current ACC/AHA guidelines [11] and confirmed in this study that absence of CAC can serve as a possible exclusion criterion for further cardiovascular risk testing, as the long-term prognosis of these patients is excellent.

Our study has some limitations. Referral to CAG was clinically driven and not available in the majority of patients. We consider the excellent outcome in long-term follow-up most important since the aim of treatment of stable angina patients is to improve prognosis by preventing myocardial infarction or death [1]. We used a 16-slice CT where currently 64-slice CT is most widely used. Finally three patients of the initial group were lost to follow-up. Hypothetically, if all these patients suffered a MACE, the NPV of CACS = 0 would have been 97.8%.

Over the past few years multi-slice computed tomography coronary angiography (CTA) is a rapid emerging non-invasive diagnostic tool for the detection of CAD.

With the introduction of CTA fast evaluation of coronary anatomy became possible, enabling stenosis detection with a high diagnostic accuracy [30]. CTA has limitations: it cannot be performed in all patients, in a small percentage of patients images are still of poor quality, and pronounced coronary calcifications can render images unevaluable. The radiation dose associated with the currently most widely used 64-slice system is considerable, and contrast agent is necessary. Due to limitations in spatial resolution, accurate grading of the severity of a coronary lesion (percentage of stenosis) is not possible on a routine basis. Because of these limitations, coronary CTA can currently not be considered a routine clinical tool with broad applicability. The rapid development of new scanners and scanning protocols will most probably overcome these limitations [31].

In the present study we show that even if soft plaque is not completely ruled out, the long-term prognosis of patients with stable symptoms and a CACS = 0 is excellent. Therefore it is unnecessary to perform a CTA in all stable patients.

In conclusion, our study shows that patients of 45 years and older with stable chest symptoms and a CACS = 0 have an excellent long-term prognosis, a high percentage of patients has no detectable calcium and CACS performs better compared with X-ECG as an initial test. Additional cost-effectiveness studies are needed to determine the exact role of CACS in clinical practice in these patients.

Acknowledgement

We thank Prof. Dr Jeroen J. Bax MD, Department of Cardiology Leiden University Medical Centre, the Netherlands for his valuable comments.

This study was supported by an unrestricted grand from the Bronovo Research Foundation, The Hague, the Netherlands

References

- 1.Fox K, Garcia MAA, Ardissino D, et al. Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris: an executive summary. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1341–3181. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies M, Hobbs F, Davis R, et al. Prevalence of left-ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure in the echocardiographic heart of England screening study: a population based study. Lancet. 2001;358:439–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05620-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox K, Cowie M, Wood D, et al. Coronary artery disease as the cause of incident heart failure in the population. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:228–36. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simoons ML, Windecker S. Chronic stable coronary artery disease: drugs vs. revascularisation. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:530–41. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutten FH, Bohnen AM, Schreuder BP, et al. Practice guideline stable angina pectoris (second revision) from the Dutch College of General Practitioners (NHG) Huisarts Wet. 2004;47(2):83–95. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: executive summary. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2375–414. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grundy S, Pasternak R, Greenland P, et al. AHA/ACC scientific statement: assessment of cardiovascular risk by use of multiple-risk-factor assessment equations: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1348–59. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel M, Peterson E, Dai D, et al. Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm0808714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibbons R, Balady G, Bricker J, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing: summary article: a report of the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1531–40. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stary H, Chandler A, Dinsmore R, et al. A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1995;92:1355–74. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenland P, Bonow R, Brundage B, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 clinical expert consensus document on coronary artery calcium scoring by computed tomography in global cardiovascular risk assessment and in evaluation of patients with chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Clinical Expert Concensus Task Force. (ACCF/AHA Writing Committee to Update the 2000 Expert Concensus Document on Electron Beam Computed Tomography) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:378–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarwar A, Shaw L, Shapiro M, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of absence of coronary artery calcification. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2009;6:675–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fletcher G, Balady G, Froelicher V, et al. Exercise standards. A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Writing Group. Circulation. 1995;91:580–615. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.2.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, et al. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–32. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arad Y, Goodman KJ, Roth M, et al. Coronary calcification, coronary disease risk factors, C-reactive protein, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events: the St. Francis Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:158–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knez A, Becker A, Leber A, et al. Relation of coronary calcium score by electron beam tomography to obstructive disease in 2115 symptomatic patients. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1150–2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1336–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuster V, Moreno PR, Fayad ZA, et al. Atherothrombosis and High-Risk plaque. Part I: evolving concepts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:937–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sehkri N, Feder G, Junghans C, et al. Incremental prognostic value of the exercise electrocardiogram in the initial assessment of patients with suspected angina: cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a2240. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nieman K, Galema T, Weustink A, et al. Computed tomography versus exercise electrocardiography in patients with stable chest complaints: real-world experiences from a fast-track chestpain clinic. Heart. 2009;95:1669–75. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.169441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mieres JH, Shaw LJ, Arai A, et al. Role of noninvasive testing in the clinical evaluation of women with suspected coronary artery disease: Consensus statement from the Cardiac Imaging Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and the Cardiovascular Imaging and Intervention Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, American Heart Association. Circulation. 2005;111:682–96. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155233.67287.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwok Y, Kim C, Grady D, et al. Meta-analysis of exercise testing to detect coronary artery disease in women. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:660–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00963-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubinshtein R, Gaspar T, Halon DA, et al. Prevalence and extent of obstructive coronary artery disease in patients with zero or low calcium score undergoing 64-slice cardiac multidetector computed tomography for evaluation of a chest pain syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:472–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marwan M, Ropers D, Pflederer T, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with obstructive coronary lesions in the absence of coronary calcification: an evaluation by coronary CT angiography. Heart. 2009;95:1056–60. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.153353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schenker MP, Sharmila D, Cho Tek Hong E, et al. Interrelation of coronary calcification, myocardial ischemia, and outcomes in patients with intermediate likelihood of coronary artery disease. A combined positron emission tomography/computed tomography study. Circulation. 2008;117:1693–700. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.717512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly JL, Thickman D, Abramson SD, et al. Coronary CT angiography findings in patients without coronary calcification. AJR. 2008;191:50–5. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akram K, O’Donnell RE, King S, et al. Influence of symptomatic status on the prevalence of obstructive coronary artery disease in patients with zero calcium score. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:533–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gottlieb I, Miller J, Arbab-Zadeh A, et al. The absence of coronary calcification does not exclude obstructive coronary artery disease or the need for revascularization in patients referred for conventional coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:627–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Werkhoven JM, de Boer SM, Schuijf JD, et al. Impact of clinical presentation and pretest likelihood on the relation between calcium score and computed tomographic coronary angiography. Am J Cardiol. 2010; article in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Sun Z, Jiang W. Diagnostic value of multislice computed tomography in coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2006;60:279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Achenbach S, Ludwig J. Is CT the better angiogram. Coronary interventions and CT imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2010;3:29–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]