Abstract

Cauda equina syndrome seems to be a very rare complication of spinal manipulations. Only few cases, in fact, were referred in literature in the past decades. Most of them are very old and poorly documented evoking doubts about the pathogenetic relationship between the spinal maneuvers and the onset of the syndrome. We observed and treated a 42-year-old patient who complained a rapid onset of saddle hypoparesthesia and urine retention only a few hours after the spinal manipulation performed for L5-S1 herniated disc. The comparison of the two following MRIs performed before and after the manipulations seems to prove a close pathogenetic relationship. The patient was operated soon after the admission to our emergency department and 1 year later he referred an incomplete recovery of the syndrome. The case offered the opportunity to update the literature. The review revealed only three cases from the beginning of the current century that confirm the rarity of the syndrome. Based on the data emerging from the official literature, safety of the manipulations and its pathogenetic aspects in causing lumbar radiculopathies are discussed.

Keywords: Cauda equina syndrome, Spinal manipulations, Herniated disc disease

Introduction

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is a well-known neurological disease caused by compression of the lumbosacral nerve roots in the lumbar vertebral canal. The literature reports many series of CES caused by tumors, vertebral canal stenosis and traumas, but only sporadic cases caused by therapeutic manipulations of the lumbar spine, such as those performed in chiropractic, CES has been recognized as an unexpected complication of physical procedures performed on patients affected by low back pain or herniated disc disease. Although no unequivocal evidence exists, it has been suggested that therapeutic manipulations may play a pathogenetic role, causing mobilization and extrusion of herniated lumbar discs with subsequent acute onset of nerve root compression. We report a case of CES observed and treated in our center in which a close correlation between rehabilitative manipulations and the onset of the CES syndrome is strongly suggested.

Materials and methods

A 42-year-old man was admitted to our emergency unit for a sudden loss of sensitivity in his lower right limb and hypoesthesia of the saddle. The patient was also suffering from overflow incontinence. Urethral catheterization showed 500 ml of urine retention. The neurological examination revealed diffuse hypoesthesia of the perineum and of the lower right limb along S1 metameric radiation. Bulbo-cavernous, ano-cutaneous and the right side Achilles tendon reflexes were absent. The patellar reflex was normal bilaterally.

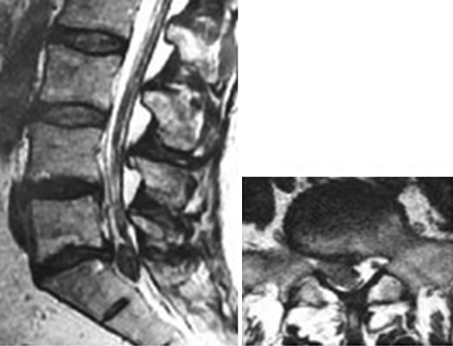

Three weeks before admission, the patient began to suffer from back pain and a painful right S1 radiculopathy, with paresthesia of the right foot. The MRI (Fig. 1) performed in another center had revealed an L5-S1 intervertebral disc hernia. As a result, the patient consulted a chiropractor who suggested a conservative treatment of the disease by spinal manipulations. The patient underwent a cycle of daily manipulations. Suddenly after the fourth manipulation, the patient started to complain of paresthesia of the saddle and of increasingly painful right leg.

Fig. 1.

MRI of a 42-year-old man carried out before vertebral manipulations treatment for right S1 radiculopathy

A complete MRI study of the spine was performed in the emergency unit to exclude spinal cord compression at the dorsal or cervical level. The lumbar tract imaging showed complete extrusion of L5-S1 disc with caudal migration of a large fragment, which almost occluded the vertebral canal, causing compression of the sacral roots (Fig. 2). The patient underwent an emergency surgical procedure consisting of right L5 laminotomy, removal of the large migrated fragment, and L5-S1 discectomy. Prompt pain resolution and mild improvement of saddle and lower limb hypoesthesia followed the surgical procedure. When the patient was discharged 6 days after surgery, he had regained his anal sphincter sensitivity, while his bladder and bowel functions were not completely restored.

Fig. 2.

A new MRI, performed after manipulations, shows the complete extrusion of the herniated disc fragment and its caudal migration

A year after the surgery, on follow-up examination, the patient referred: mild persistent sensitivity deficits and paresthesias of the right lower limb and of the S1 metameric region, normal urinary function, and bowel movements only after taking laxatives. In particular, he reported complete sexual impotence.

Results

Therapeutic manipulation of the spine has become increasingly popular and is currently one of the most frequent conservative treatment options for painful spine syndromes. It is generally considered by practitioners and patients to be a safe and effective procedure to treat a large variety of pathologies without any significant complications. Available literature data on spinal manipulation of patients with lumbar disc herniation has recently been reviewed by Oliphant [1] to evaluate the safety and incidence of complications of this procedure. He shows that chiropractic spinal manipulation is a safer procedure when compared to surgery or NSAID treatments and that the risk of CES—as a iatrogenic complication—is very low, estimating its occurrence to be less than 1 in 3.7 million manipulations. Some authors have confirmed the safety of spinal manipulations and have expressed their skepticism about published cases that attribute CES to spinal manipulations [2–5]. They argue that such cases are not scientifically well documented, suggesting that lack of evidence of a clear temporal relationship between manipulation procedures and the onset of symptoms does not allow for the distinction between iatrogenic damage and the natural evolution of the underlying disease and that therefore some cases of CES reported in the literature might have been wrongly attributed to spinal rehabilitative manipulations.

Having observed and treated a CES syndrome in an emergency situation—which was almost certainly secondary to spinal manipulation maneuvers—has encouraged us to report our case in order to review the pathogenesis of this syndrome and the safety of spinal manipulations in general. We first conducted a review of the literature to update the case reports and to study the available data in depth. A first review of the international data was carried out by Haldeman and Rubinstein [6], who identified 26 cases of spinal manipulation-related CES, many of which had been reported some decades earlier. In the vast majority of such cases, the cauda equina syndrome was secondary to vertebral manipulations performed under anesthesia; the use of general anesthesia in spinal manipulations is no longer a common practice. In our research, five more cases of CES were found [7–9], of which two had been reported before 1992 [10, 11] and had not been included in the review by Haldeman and Rubinstein. We also included an article by Silver who mentions an author who allegedly was the first to recognize and describe a case of CES in 1889, which occurred after a manipulation under general anesthesia [12]. Apart from this case which represents only a historical curiosity, the data from the literature are surprising. It was already known that such a causal relationship was sporadic, but the most surprising finding was the discrepancy between the small number of published cases and the increasing frequency of manipulation procedures performed for the treatment of vertebral nerve root pathologies. Given the increased frequency of spinal manipulations, one might expect an increase in the number of CES-related cases. Our assumption is that many of the cases observed were included in larger studies about CES with other etiologies or that many of them had not been published. Although the latter hypothesis is the most probable, it still does not explain the relatively low number of cases with respect to the total number of procedures performed. Nyiendo and Haldeman [13] failed to reveal major complications in a prospective evaluation of 2,000 patients attending a chiropractic college clinic while Haldeman and Rubinstein [6] were able to find and report 3 cases of acute worsening of cauda equina syndrome among 88 malpractice claims against chiropractors.

The pathogenesis of cauda equina syndrome still remains to be understood. Two main hypotheses exist: the mechanical compression of the lumbar roots and the ischemic damage to the spinal cord or to the cauda equina [8]. According to the first hypothesis, the syndrome is due to the massive compression of the lumbar roots exerted by a large hernia which is violently expelled during the spinal manipulations or, less frequently, by an epidural hematoma which results from the traumatic rupture of a blood vessel [9]. In the second hypothesis, the neurological damage is attributed to the ischemia of the blood vessels of the spinal cord or the cauda equina. However, it should be noted that the vascular pathogenesis in CES—either due to direct vessel damage or to ischemia—is very rare in the lumbar spine but is frequent in the cervical spine. In fact, data from the literature report a high incidence of neurologic sequelae in the spinal cervical tract induced by manipulations that very frequently cause the dissection of the vertebral arteries [14].

A major contribution to the investigation and understanding of the pathogenesis of CES has been provided by MRI. Only with the routine use of this imaging technique, it has been possible to obtain a correct morphological determination of the clinical syndromes due to disc hernias and, more importantly, to detect CES of vascular origin. Therefore, the cases reported recently are more sporadic, but they provide more evidence and details with respect to those described in the past.

In the case presented here, two main features strongly suggest a direct relationship between rehabilitative manipulations and CES: the extensive diagnostic imaging examinations performed immediately before and shortly after the spinal manipulation show a deterioration of the disk herniation and the time relationship between the spinal manipulations and the onset of the clinical syndrome. The pre-treatment MRI shows a voluminous fragment of the L5-S1 intervertebral disc posteriorly herniated, causing the displacement and then compression of the S1 nerve root (Fig. 1). The second set of MRI images was obtained soon after the patient was admitted into our emergency unit and within 12 h after the spinal manipulation. The comparison of the two images clearly shows the caudal migration of the large disc fragment revealed on the previous MRIs (Fig. 2).

Concerning the relationship between the time of the manipulation and the onset of the syndrome, only a few hours had elapsed between the manipulations and the onset of CES. At the time of the first MRI exam, the patient was suffering only from a painful radiculopathy. Less than 12 h after a chiropractor performed a cycle of spinal manipulations in an attempt to treat the hernia conservatively, the patient arrived at our emergency unit with neurological deficits, such as bowel and bladder dysfunction.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the case presented provides evidence of a strong pathogenetic relationship between spinal manipulations and the deterioration of the clinical syndrome. Indeed, it seems that the shift from simple radiculopathy to a more severe compression of the sacral roots with bowel and bladder dysfunction occurred soon after the physical treatment. In general we agree with the safety of spinal manipulations as reported in the scientific literature. But indeed there is a minimal risk of a deterioration of pre-existing conditions or the onset of CES.

Given the clinical and radiologic presentation of this case before performing the spinal manipulations, it can be argued that a surgical, rather than a conservative treatment, should have been chosen at that time. However, it is important to stress that almost every day we observe cases in which the choice of treatment is not made by physicians but by practitioners of alternative medicine who seldom provide the patient with adequate information about the risks involved in alternative medicine.

Consequently, the possibility of a clinical deterioration in patients with radiculopathy and the diagnosis of lumbar hernia have to be considered when choosing the treatment. Such possibility may occur more frequently in the case of the extruded disc fragment revealed by MRI. Therefore, we suggest that all patients suffering from radiculopathy due to lumbar hernias should be clearly informed about the potential, even if rare, complications of spinal manipulations.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Oliphant D. Safety of spinal manipulation in the treatment of lumbar disk herniations: a systematic review and risk assessment. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2004;27:197–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terrett AG, Kleynhans AM. Complications from manipulation of the low back. Chiropr J Aust. 1992;27:129–140. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assendelft WJ, Bouter LM, Knipschild PG. Complications of spinal manipulation: a comprehensive review of the literature. J Fam Pract. 1996;42:475–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernst E. Prospective investigations into the safety of spinal manipulation. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2001;21:238–242. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(00)00262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lisi AJ, Holmes EJ, Ammendolia C. High-velocity low-amplitude spinal manipulation for symptomatic lumbar disk disease: a systematic review of the literature. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2005;28:429–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haldeman S, Rubinstein SM. Cauda equina syndrome in patients undergoing manipulation of the lumbar spine. Spine. 1992;17:1469–1473. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199212000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markowitz HD, Dolce DT. Cauda equina syndrome due to sequestrated recurrent disk herniation after chiropractic manipulation. Orthopedics. 1997;20:652–653. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19970701-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morandi X, Riffaud L, Houedakor J, et al. Caudal spinal cord ischemia after lumbar vertebral manipulation. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71:334–337. doi: 10.1016/S1297-319X(03)00154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solheim O, Jorgensen JV, Nygaard OP. Lumbar epidural hematoma after chiropractic manipulation for lower-back pain: case report. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:E170–E171. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000279740.61048.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malmivaara A, Pohjola R. Cauda equina syndrome caused by chiropraxis on a patient previously free of lumbar spine symptoms. Lancet. 1982;2:986–987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(82)90184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallinaro P, Cartesegna M. Three cases of lumbar disc rupture and one of cauda equina associated with spinal manipulation (chiropraxis) Lancet. 1983;1:411. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(83)91519-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silver JR. The earliest case of cauda equina syndrome caused by manipulation of the lumbar spine under a general anaesthetic. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:51–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nyiendo J, Haldeman S. A prospective study of 2000 patients attending a chiropractic college teaching clinic. Med Care. 1987;25:516–527. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198706000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KP, Carlini WG, McCormick GF, et al. Neurologic complications following chiropractic manipulation: a survey of California neurologists. Neurology. 1995;45:1213–1215. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.6.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]