Abstract

Most cells express a panel of different G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) allowing them to respond to at least a corresponding variety of extracellular ligands. In order to come to an integrative well-balanced functional response these ligand–receptor pairs can often cross-regulate each other. Although most GPCRs are fully capable to induce intracellular signalling upon agonist binding on their own, many GPCRs, if not all, appear to exist and function in homomeric and/or heteromeric assemblies for at least some time. Such heteromeric organization offers unique allosteric control of receptor pharmacology and function between the protomers and might even unmask ‘new’ features. However, it is important to realize that some functional consequences that are proposed to originate from heteromeric receptor interactions may also be observed due to intracellular crosstalk between signalling pathways of non-associated GPCRs.

Keywords: G protein-coupled receptor, receptor dimerization, receptor oligomerization, receptor trafficking, cooperativity, crosstalk, G protein, signal transduction

G protein-coupled receptors and cellular communication

A sophisticated biochemical communication network regulates coordinated functioning of individual cells within the human body. An important part of this network consists of extracellular messenger molecules (i.e. ligands) and cognate receptor proteins that are present on the cellular surface (Ben-Shlomo et al., 2003). The G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are by far the largest family of membrane-associated receptors, and are characterized by the presence of seven transmembrane (TM) α-helices that are connected by alternating intracellular and extracellular loops (i.e. ILs and ELs respectively). The human genome encodes approximately 800 different GPCRs that are responsive to a plethora of endogenous (e.g. ions, lipids, biogenic amines, peptides and glycoproteins) and exogenous (e.g. odorants, tastants, photons and therapeutic drugs) ligands (Lagerstrom and Schioth, 2008). Not surprisingly, GPCRs are involved in the regulation of nearly all processes in our body and their dysfunction contributes to numerous human pathologies (Dorsam and Gutkind, 2007; Smit et al., 2007). Hence, GPCRs are today's favourite drug targets with ∼40% of all current therapeutic molecules acting on members of this protein family.

Binding of an agonist to the extracellular site of the GPCR (i.e. N-terminus, ELs and/or pocket that is formed by the 7TM helices) induces conformational changes in the 7TM and intracellular domains of the receptor, allowing coupling and activation of specific heterotrimeric G proteins (Oldham and Hamm, 2008; Nygaard et al., 2009). Activated G proteins dissociate from the GPCR to relay the signal to downstream effector proteins. Subsequent phosphorylation of the intracellular domains of activated GPCRs by GPCR kinases (GRKs) promotes the recruitment of β-arrestins (Kelly et al., 2008; Tobin, 2008). Bound β-arrestin inhibits G protein signalling by hindering GPCR–G protein coupling and by recruiting proteins involved in receptor endocytosis. However, β-arrestin can also scaffold new signalling cascade components to the activated GPCR, thereby initiating a second wave of intracellular signalling (Lefkowitz and Shenoy, 2005).

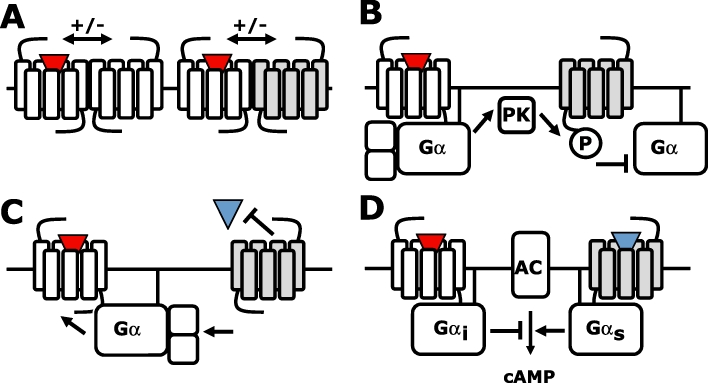

Most of our cells express several dozen different GPCR subtypes, which can be variably mixed and matched in different cell types, and are consequently responsive to at least a corresponding number of ligands (Vassilatis et al., 2003; Gurevich and Gurevich, 2008; Regard et al., 2008). Importantly, individual ligand–receptor combinations do generally not operate in isolation, but may rather ‘talk’ to each other to come to a balanced cellular response to two or more simultaneous stimuli. This crosstalk can occur at (a combination of) various levels along the GPCR signal transduction pathway. First of all, GPCRs can allosterically interact with each other by forming homomeric or heteromeric (i.e. between similar or different receptor subtypes respectively) assemblies (Figure 1A). Second, GPCRs can desensitize other GPCRs via second messenger-dependent protein kinases A or C (Figure 1B) (Vazquez-Prado et al., 2003; Kelly et al., 2008). Third, GPCRs may impair other GPCRs by scavenging shared signalling and/or scaffolding proteins (e.g. G proteins and β-arrestins) that are limiting for receptor signalling (Figure 1C) (Schmidlin et al., 2002; Nijmeijer et al., 2010). And finally, GPCRs can activate distinct signal transduction pathways that may converge at downstream signalling hubs, as for example the opposite regulation of adenylate cyclase by Gi/o- and Gs-coupled GPCRs or regulation of intracellular Ca2+ levels by Gi/o- and Gq-coupled GPCRs (Figure 1D) (Natarajan et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

Crosstalk between G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). (A) Intermolecular communication between GPCR homomers and heteromers. (B) Agonist (red triangle)-induced signalling of one GPCR can desensitize other GPCRs via second messenger-dependent protein kinases (PK) A or C. (C) Agonist-induced signalling of one GPCR depletes a shared pool of available G proteins, thereby inhibiting other GPCRs. (D) Signalling pathways of Gi/o- and Gs-coupled GPCRs converge on the regulation of adenylyl cyclase (AC).

Heteromerization between different GPCR subtypes can significantly modify functional characteristics of the individual protomers, including subcellular localization, ligand binding cooperativity and proximal signalling (Levoye et al., 2006b; Springael et al., 2007; Milligan, 2009). However, GPCR heteromer-induced changes in biochemical GPCR signalling properties are often difficult to distinguish unambiguously from downstream crosstalk between non-associated GPCR pairs. In this review, we will focus on the question ‘do GPCRs that walk hand-in-hand, also talk hand-in-hand?’.

GPCR oligomerization

Dimerization and/or higher order oligomerization of otherwise non-functional protomers is a common phenomenon for most cell surface receptor families. Oligomerization of three to five subunits is required to form a ligand-gated ion channel, whereas ligand-induced dimerization is mandatory for activation and signalling of 1TM-domain receptors such as cytokine receptors, receptor tyrosine and serine/threonine kinases (Heldin, 1995; Marianayagam et al., 2004). Also class C GPCRs exist and function as obligate dimers (Pin et al., 2003; 2009;). For example, the γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) B receptor consists of two different 7TM subunits GABAB1 and GABAB2 that are non-functional when expressed on their own. The GABAB1 subunit is retained in the endoplasmatic reticulum as export through the Golgi is prevented by binding of coat protein I complex (COP1) to the RXR retention motif in its C-tail (Brock et al., 2005). However, the GABAB2 subunit masks this COP1 binding site through a coiled–coil interaction of their C-tails, allowing trafficking of the heteromeric GABAB receptor to the cell surface (Margeta-Mitrovic et al., 2000; Pagano et al., 2001). Moreover, the GABAB subunits have complementary roles in GABA-induced signalling, with GABA binding exclusively to the N-terminal extracellular domain (NTED) of GABAB1 and G proteins exclusively being activated by GABAB2 upon transactivation of this subunit by the agonist-occupied GABAB1 (Galvez et al., 2001; Duthey et al., 2002; Havlickova et al., 2002; Kniazeff et al., 2002). Similarly, the umami and sweet taste receptors are heterodimeric assemblies of T1R3 in combination with T1R1 or T1R2 respectively (Zhao et al., 2003). Indeed, T1R3 knockout mice show diminished detection of both umami and sweet taste, whereas only the umami or sweet sensation was affected in T1R1 and T1R2 knockout mice respectively (Damak et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2003). Finally, the calcium sensing receptor and eight metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGlu) are homodimers in which the two NTEDs are linked by disulfide bonds (Romano et al., 1996; Ray et al., 1999). Agonist-induced movement of these NTEDs relative to each other results in activation of these receptor dimers (Pin et al., 2005). Interestingly, constitutive homodimerization of class B secretin receptors was found to facilitate G protein coupling, which is mandatory for high affinity secretin binding (Harikumar et al., 2006; Gao et al., 2009). Hence, functional class C (and possibly class B) receptors (i.e. capable to induce intracellular signalling in response to agonist stimulation) are macromolecular assemblies of two 7TM subunits that are non-functional on their own.

In contrast to class C (and possibly class B) GPCR 7TM subunits, most class A GPCRs are fully capable to interact as single 7TM units with their ligands and intracellular protein partners (i.e. heterotrimeric G protein, GRK or β-arrestin) in a 1:1:1 stoichiometry, as observed in recent studies using purified GPCR monomers that were refolded in small lipid bilayer nanodiscs or detergent micelles (Bayburt et al., 2007; Hanson et al., 2007; White et al., 2007; Whorton et al., 2007; 2008; Kuszak et al., 2009; Arcemisbehere et al., 2010; Bayburt et al., 2010; Tsukamoto et al., 2010). Nonetheless, increasing experimental evidence suggests that most if not all class A GPCRs can form homomers and/or heteromers (Ferre and Franco, 2010). Already in 1975, negative cooperativity in radioligand binding studies suggested that β-adrenoceptors might be assembled as homodimers in erythrocyte membrane preparations (Limbird et al., 1975). Even though biochemical evidence for the existence of class A GPCR dimers (e.g. cross-linking, co-immunoprecipitation, photo-affinity labelling and radiation inactivation experiments) was also reported in the following two decades (Bouvier, 2001), the concept that GPCRs can physically interact with each other became only more widely accepted after the identification of the aforementioned, obligatory GABAB heterodimer in the mid- to late-1990s (Romano et al., 1996; Jones et al., 1998; Kaupmann et al., 1998; White et al., 1998). New experimental approaches, including protein-fragment complementation (PFC) techniques and resonance energy transfer (RET)-based methods (see below), have catalysed the identification of GPCR homomers and heteromers in heterologous expression systems during the last decade (Ciruela et al., 2010; Khelashvili et al., 2010). Hitherto, however, confirming the presence of GPCR assemblies in native cells is still technically challenging and remains limited to only a few examples (Pin et al., 2007; Ferre et al., 2009; Albizu et al., 2010).

Evidence for GPCR oligomerization

Over the last 30 years, a wide variety of biochemical and biophysical methodologies have been applied to collect evidence for GPCR oligomerization, mostly using heterologously expressed GPCR constructs that are engineered to include epitope tags (e.g. HA, FLAG or myc) or biosensors [e.g. green fluorescent protein (GFP) variants or luciferase] to allow or facilitate their detection. In this respect, it is important to verify that receptor expression levels are physiologically relevant to avoid artificial aggregation. Moreover, GPCR interactions and functional consequences hereof that were identified in heterologous expression systems should be validated in native cells to confirm their physiological relevance (Pin et al., 2007; Ferre et al., 2009).

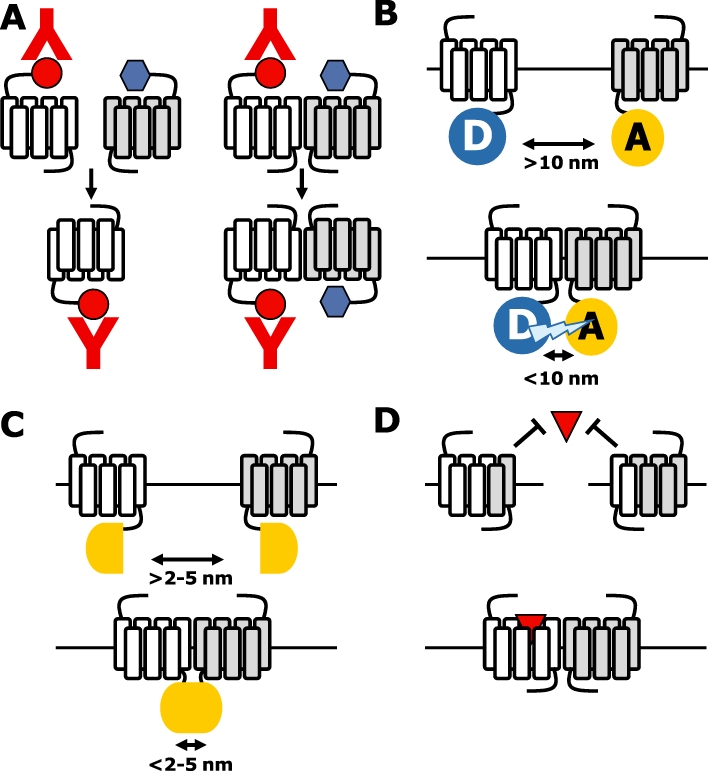

The most widely used biochemical proof for physical interactions between GPCRs is by co-immunoprecipitation of these assemblies from solubilized cells using a specific antibody against one protomer, followed by immunoblotting of the SDS-PAGE-resolved samples using a specific antibody against the other protomer (Figure 2A) (Milligan and Bouvier, 2005). Disruption of the cellular integrity may cause aggregation of non-associated receptors, which should be taken into account by comparing cells that co-express both receptors of interest, with cells that express the individual receptor subtypes and are mixed in a 1:1 ratio prior to solubilization. Epitope-tagged GPCRs are routinely used in co-immunoprecipitation experiments, which allow the use of highly specific antibodies that have high affinity for their respective tag. However, if high-quality GPCR-specific antibodies are available this method is one of the few that can be used to detect endogenous GPCR oligomers in native cells.

Figure 2.

Detection of G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) oligomers. (A) The ‘blue’-tagged GPCR is only co-immunoprecipitated if physically associated with the ‘red’-tagged receptor (i.e. bottom-right panel). (B) Resonance energy transfer between donor and acceptor molecules that are fused to GPCR occurs when they are brought in close proximity (<10 nm) by interacting GPCR. (C) Protein-fragment complementation of non-functional biosensor protein fragments occurs when they are brought in close proximity (<2–5 nm) by interacting GPCRs as fusion proteins. (D) Two non-functional GPCRs are functionally reconstituted upon co-expression in the same cell, for example by domain-swap dimerization.

The last decade, RET- and PFC-based methods are routinely used to detect GPCR oligomerization in living cells (Ciruela et al., 2010). RET between a fluorescent (FRET) or bioluminescent (BRET) donor and a suitable fluorescent acceptor only occurs if these molecules are brought in close proximity (i.e. <10 nm) by interacting proteins (Figure 2B). To this end, FRET-compatible donor or acceptor variants of GFP are fused in frame to the C-terminus of the GPCRs of interest. Hitherto, up to three compatible fluophores have been simultaneously used to detect the close proximity of (at least) three GPCRs in a so-called sequential three-colour FRET (Lopez-Gimenez et al., 2007; Canals et al., 2009). If the RET donor is the bioluminescent enzyme Renilla reniformis luciferase (Rluc), BRET can be measured if it is brought in close proximity to green (i.e. BRET2 using DeepBlue C as substrate) or yellow fluorescent protein (i.e. BRET using Coelenterazine H as substrate) by interacting GPCRs. In addition, BRET can be combined with FRET between compatible fluorescent proteins in sequential RET to detect close proximity between three GPCRs (Carriba et al., 2008). Variants of GFP and Rluc can be genetically split into two non-functional protein fragments, which are fused in frame to the C-terminus of GPCRs (Figure 2C). If these split protein fragments are brought in close proximity by interacting GPCRs they will reconstitute into a functional biosensor (Guo et al., 2008). While reconstituted Rluc fragments can unfold and separate upon dissociation of interacting protein complexes, the refolding of GFP variants is irreversible resulting in an artificial stabilization of (transient) interactions between GPCR–PFC fusion proteins (Michnick et al., 2007). Combining the PFC method with BRET measurements allows detection of close proximity between four GPCRs (Guo et al., 2008; Nijmeijer et al., 2010). Fusion of a SNAP (or CLIP) tag to the N-terminus of GPCRs allows covalent labelling of surface expressed GPCRs with membrane-impermeant time-resolved FRET (trFRET) compatible donor (e.g. Eu3+ or Tb2+ cryptate) and acceptor (e.g. D2, Red) fluophores (Maurel et al., 2008; Alvarez-Curto et al., 2010). trFRET relies on long-lived lanthanide (donor) emission versus short acceptor emission lifetime. Acceptor emission due to direct acceptor excitation decays rapidly, allowing detection of long-lived (indirect) energy transfer-mediated acceptor emission. These trFRET fluophores can also be conjugated to antibodies and even more interesting to GPCR ligands (Maurel et al., 2004; Albizu et al., 2010). Ligand (antagonist)-based trFRET has very recently successfully been used to detect endogenous oxytoxin receptor oligomers in mammary gland (Albizu et al., 2010). Even though well-designed RET- and/or PFC-based experiments may provide compelling evidence for specific GPCR interactions, one has to keep in mind that close proximity rather than physical interactions between proteins is detected.

Convincing evidence for direct physical interactions between GPCRs is provided by functional complementation experiments in which two non-functional receptor protomers are engineered and co-expressed to obtain a functional (quasi)-heteromeric receptor complex (Figure 2D). The best-known example of functional receptor complementation is provided by nature herself: the obligatory heteromeric GABAB receptor in which the NTED of GABAB1 is required for ligand binding, whereas the 7TM domain of GABAB2 activated the G protein (Jones et al., 1998; Kaupmann et al., 1998; White et al., 1998). The glycoprotein hormone receptors distinguish themselves from other class A GPCRs by having an extended NTED, which is exclusively involved in hormone binding (Osuga et al., 1997; Fan and Hendrickson, 2005). Taking advantage of this modular nature of hormone–receptor and receptor–G protein interactions, luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSHR) mutants were engineered in which either hormone binding to the NTED or G protein activation by the 7TM domain was disrupted (Ji et al., 2002; 2004; Lee et al., 2002). Interestingly, co-expression of these LHR or FSHR mutants restored hormone-induced cAMP production, indicating that these loss-of-function mutants can form functional dimers. Moreover, transgenic co-expression of binding- and signalling-deficient LHR mutants in Leydig cells of male hypogonadal LHR knockout mice at physiological levels, restored LH-induced Leydig cell differentiation, testosterone production, gonadal development to sexual maturation and spermatogenesis, confirming for the first time the significance of intermolecular interactions between co-expressed GPCRs in a physiological context (Rivero-Muller et al., 2010). The mode of action of this functional complementation remains somewhat puzzling, however, as some of these binding-deficient receptor mutants can also be transactivated by NTEDs tethered to a glycosyl phosphatidylinositol moiety or CD8 TM domain. This suggests that (dimeric) interactions between two 7TM domains are not required for this functional rescue (Ji et al., 2002; 2004;). In contrast to the modular glycoprotein hormone receptors, the majority of class A GPCRs bind their ligands within or near the pocket formed by the 7TM domain (Kristiansen, 2004). Consequently, ligand binding and receptor activation domains of these GPCRs cannot be easily separated. However, co-expression of two binding-deficient histamine H1 receptors (H1R) with a single mutation in TM3 or TM6 (i.e. H1R-D3.32A and H1R-F6.52A respectively) restored ligand binding, revealing a physical interaction between the two receptor mutants (Bakker et al., 2004b). As only TM1–5 of H1R-F6.52A and TM6–7 of H1R-D3.32A can contribute to a functional H1R binding pocket, these data suggest that these dimers are organized in a reciprocal domain-swap configuration. A similar domain-swap arrangement was shown by rescued ligand binding upon co-expression of M3 muscarinic receptor/α2C-adrenoceptor chimeras in which TM6–7 domains were reciprocally exchanged (Figure 2D) (Maggio et al., 1993). Interestingly, co-expression of binding-deficient angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) constructs with a single mutation in TM3 or TM5 also restored binding of angiotensin II and related analogues (Monnot et al., 1996).

Do GPCRs walk hand-in-hand?

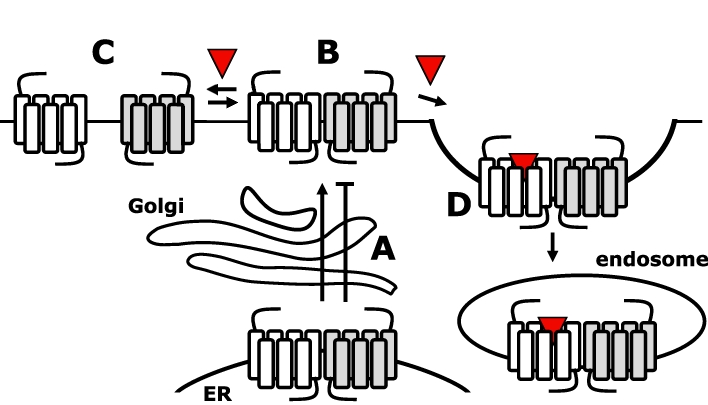

A large number of class A and C GPCR subtypes are not delivered to the cell surface when transfected in heterologous cells, and it has been proposed that heteromerization of GPCRs that share similar spatiotemporal expression profile in native cells might be required for proper folding and export of these from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the cell surface (Figure 3A) (Minneman, 2007; 2010; Achour et al., 2008). Indeed, the coiled–coil interaction between the C-tails of GABAB1 and GABAB2 is required for cell surface targeting of the heteromeric GABAB receptor, confirming that GPCR homomers and heteromers are formed during early biosynthesis and protein maturation in the ER. Heteromerization of the β2- or α1B-adrenoceptor with the α1D-adrenoceptor is essential for cell surface targeting of the latter receptor in heterologous cells, whereas co-expression with 26 other related class A GPCRs did not promote surface expression of the α1D-adrenoceptor (Hague et al., 2004; Uberti et al., 2005). On the contrary, various naturally occurring GPCR splice variants and mutants have been reported to trap co-expressed wild-type counterparts in the ER by forming heteromeric assemblies (Figure 3A) (Zhu and Wess, 1998; Coge et al., 1999; Karpa et al., 2000; Seck et al., 2003; Calebiro et al., 2005; Pidasheva et al., 2006; van Rijn et al., 2008). For example, natural occurring rat histamine H3 receptor (H3R) splice variants that lack TM7 impair cell surface targeting of wild-type H3R (Bakker et al., 2006). Interestingly, the expression levels of these truncated isoforms and wild-type H3R in rat brain are oppositely modulated by the convulsant pentylenetetrazole, resulting in increased H3R activity, whereas high-fat diet induced down-regulation of the dominant negative GIP receptor splice variant resulting in an up-regulation of wild-type GIP receptors in obese mice (Harada et al., 2008). In addition, dominant negative receptor mutants have been engineered by introducing ER-retention signals into the C-tail of GPCRs or site-directed mutation of ER-export motifs. Substitution of the C-tail of the β2-adrenoceptor with the C-tail ER-retention motif of GABAB1 resulted in an ER-trapped receptor mutant, which also prevented cell surface targeting of wild-type β2-adrenoceptor (Salahpour et al., 2004). Likewise, fusion of the ER-retention motif of the α2C-adrenoceptor to the C-tail of the CXC-chemokine receptor 1 (CXCR1) impaired its trafficking to the cell surface (Wilson et al., 2005). Moreover, this ER-retained CXCR1 mutant inhibited cell surface trafficking of wild-type CXCR1 and the closely related CXCR2, by forming homomers and heteromers respectively. In contrast, cell surface delivery of co-expressed α1A-adrenoceptor was not affected, which correlated with the observation that CXCR1 and α1A-adrenoceptor do not form heteromers. The importance of a correct quaternary structure for cell surface delivery was furthermore demonstrated by a α1B-adrenoceptor mutant in which hydrophobic residues in TM1 and TM4 were Ala-substituted (Lopez-Gimenez et al., 2007; Canals et al., 2009). This TM1–TM4 mutant was trapped in the ER and displayed an altered oligomeric organization in comparison with wild-type receptors as indicated by sequential three-colour FRET analysis. Interestingly, the cell-permeant α1B-adrenoceptor-antagonist prazosin changed the quaternary structure of TM1–TM4 mutants to an oligomeric organization that resembles wild-type α1B-adrenoceptor. In addition, prazosin acted as pharmacological chaperone by promoting terminal N-glycosylation and maturation, resulting in cell surface delivery of this TM1–TM4 mutant (Canals et al., 2009). Several other examples of pharmacological chaperones that restore cell surface delivery of disease-linked receptor mutants have been reported (Bernier et al., 2004). However, whether this pharmacological rescue involves changes in quaternary receptor organization remains to be investigated.

Figure 3.

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are walking hand-in-hand. (A) GPCR oligomerization in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is required for cell surface delivery; however, oligomerization may also retain GPCRs in the ER. (B and C) GPCRs exist at the cell surface in an equlibrium between oligomers and monomers. The transition between these configurations may be affected by ligands. (D) Agonist stimulation of one protomer results in internalization of the heteromeric assembly.

Collectively, most data suggest that receptor oligomers are preassembled in the ER and ‘walk hand-in-hand’ to the cell surface. Obviously, the covalent disulfide-bonded homomeric class C GPCRs keep on walking hand-in-hand at the cell surface, whereas the heteromeric GABAB receptor is stabilized by a coiled–coil configuration of the C-tails and direct interactions of the NTEDs (Pin et al., 2005). For long, the stability of class A GPCR oligomers has been an enigma, although RET data suggest that most GPCRs remain organized as oligomers (Figure 3B). In addition, mutational analysis revealed that heteromers between the dopamine D2, adenosine A2A and the cannabinoid CB1 receptors are stabilized by electrostatic interactions between Arg-rich motifs in IL3 of D2 and A2A receptors and phosphorylated casein kinase 1/2 sites in IL3 and C-tail of the CB1 receptor, and the C-terminus of the A2A receptor (Borroto-Escuela et al., 2010; Navarro et al., 2010). In addition, the Arg-rich motif in IL3 of the dopamine D2 receptor is involved in a stabilizing electrostatic interaction with a di-glutamate motif in the C-terminus of the serotonin 5-HT2A and D1 receptor (Lukasiewicz et al., 2009; 2010;). Recently, however, the lateral mobility of one protomer was monitored using dual fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) microscopy upon antibody immobilization of the other protomer at the cell surface (Dorsch et al., 2009; Fonseca and Lambert, 2009). To this end, different GFP variants were fused to the N- or C-terminus of the GPCRs. Immobilization of one YFP-β2-adrenoceptor almost completely impaired lateral diffusion of at least four co-expressed β2-adrenoceptor-CFP fusion proteins into the bleached region of the cell membrane, suggesting that receptors form stable higher order homomers (Dorsch et al., 2009). In contrast, the mobility of β1-adrenoceptor and D2 receptor was only modestly affected by the antibody immobilization of their homomeric counterparts, suggesting that these receptors form rather transient homomers (Figure 3C) (Dorsch et al., 2009; Fonseca and Lambert, 2009). Intensity imaging of M1 muscarinic receptors that were labelled with a slowly dissociating fluorescent antagonist using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy indicates that transient M1 receptor homodimers are being formed and/or fall apart within seconds. This short-lived nature of M1 receptor homodimers was confirmed by recording the lateral mobility trajectory of dual-colour labelled receptors. Approximately 30% of the M1 receptors was engaged in homodimers at any given moment, whereas higher order oligomers were never detected for this receptor (Hern et al., 2010). Interestingly, the apparent transient nature of β1-adrenoceptor, D2 and M1 receptor homodimers as observed in these imaging-based studies is in contrast with earlier BRET studies for these receptors, which indicated that the vast majority of these receptors exist as constitutive dimers at nearly physiological expression levels (Mercier et al., 2002; Goin and Nathanson, 2006; Guo et al., 2008). In addition, BRET data indicated that β1- and β2-adrenoceptors have equal propensities to form homodimers and heterodimers (Mercier et al., 2002), whereas D2 receptor homodimerization was confirmed in cross-linking and functional complementation experiments (Guo et al., 2008; Han et al., 2009). In fact, higher order D2 receptor oligomers have been detected using PFC in combination with BRET analysis; however, it should be kept in mind that the transient nature of D2 receptor interactions might be obscured the permanent reconstitution of the sensor proteins from their split fragments. Higher order homomers and heteromers (i.e. trimeric and tetrameric assemblies) have also been detected for other class A GPCRs using this PFC-BRET analysis (Gandia et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2008; Sohy et al., 2009; Nijmeijer et al., 2010), but also using three-colour FRET (Lopez-Gimenez et al., 2007; Canals et al., 2009), and sequential RET studies (Cabello et al., 2009; Navarro et al., 2010). In addition, GABAB dimers (i.e. homodimers of heterodimers) have been detected by trFRET-SNAP (Maurel et al., 2008).

Hitherto, regulation of GPCR oligomerization dynamics at the cell surface upon ligand binding remains still controversial (Figure 3B and C). For example, the agonist isoproterenol and antagonist propranolol did not affect the stability or amount of β1- and β2-adrenoceptor homomers in FRAP experiments (Dorsch et al., 2009). Similarly, isoproterenol had little effect on FRET efficiency between purified and reconstituted β2-adrenoceptor homomers, while the inverse agonist ICI 118 551 significantly increased the FRET efficiency (Fung et al., 2009). On the other hand, isoproterenol dose-dependently increased BRET efficiency between β2-adrenergic receptors in living cells (Angers et al., 2000). As RET efficiency is determined by both distance and orientation of donor and acceptor dipole moments, ligand-induced changes in RET intensity do not necessarily reflect de novo formation or dissociation of GPCR oligomers, but may also represent conformational changes in existing oligomers. In addition, Western blot analyses revealed that agonist or inverse agonist treatment of β2-adrenoceptor-expressing membranes shifted the equilibrium towards the homomeric or monomeric state respectively (Hebert et al., 1996). Similar inconsistencies have been reported for other GPCRs, and are most presumably related to methodological limitations. Interestingly, agonists increased trFRET between SNAP-tagged M3 receptors but decreased FRET between M3 receptors that were C-terminally fused to GFP variants (Alvarez-Curto et al., 2010). As encaged lanthanides have no donor dipole constraint, the trFRET efficiency between covalently bound SNAP-tag fluophores is minimally effected by orientation (Selvin and Hearst, 1994) and the observed increase in trFRET may in fact reflect an agonist-induced increase in M3 receptor oligomerization.

If GPCRs exist as (relatively) stable oligomers on the cell surface or become so upon agonist stimulation, one might expect that they keep walking hand-in-hand during internalization (Figure 3D). Engineering a ‘homodimer’ between the wild-type and a RASSL (i.e. receptor activated solely by synthetic ligands) β2-adrenoceptor, it was demonstrated that agonist binding to one of the protomers induces internalization of these ‘homodimers’ (Sartania et al., 2007). Likewise, D1 and D2 receptor heteromers internalize upon selective activation of one of the two protomers (So et al., 2005). Interestingly, the fate of the internalized vasopressin V1A and V2 receptor heteromers was found to be dependent on which protomer is being activated. Stimulation with V1A receptor-selective agonist confers a V1A receptor-like endocytosis/recycling profile to the V1A–V2 receptor heteromer, whereas stimulation with a non-selective agonist results in V2 receptor-like intracellular accumulation of the V1A–V2 receptor heteromer (Terrillon et al., 2004).

Taken together, oligomerization seems to be required for cell surface expression of most GPCRs. The fate of GPCR oligomers at the cell surface is GPCR subtype-dependent, with some GPCRs forming short-lived, transient oligomers, whereas others are organized as long-lived, stable (higher order) oligomers. GPCR oligomers internalize upon agonist stimulation of one of the protomer.

Do GPCRs talk hand-in-hand?

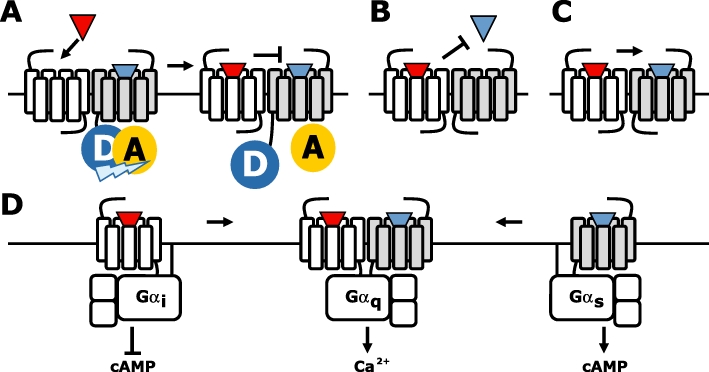

Clear evidence that GPCRs ‘talk hand-in-hand’ comes from the aforementioned obligatory heterodimer GABAB, in which one protomer (i.e. GABAB1) is exclusively responsible for protein binding, whereas only the other protomer (i.e. GABAB2) can activate heterotrimeric G proteins. Such functional asymmetry in protomer functioning has also been observed in class A GPCR oligomers. Despite the fact that GPCR monomers can efficiently couple to G proteins and β-arrestins in response to agonist stimulation (see below), functional asymmetry is often apparent once they are engaged in homomeric and/or heteromeric assemblies. For instance, ligand binding to one protomer can affect the associated protomer through intermolecular allosteric interactions. Propagation of conformational changes from one to the other protomer has been directly shown within the α2A-adrenoceptor/µ-opioid receptor (µOR) heterodimer (Vilardaga et al., 2008). Binding of morphine to the µOR triggers a conformational change in the associated norepinephrine-occupied α2A-adrenoceptor, as detected by a decrease in the norepinephrine-induced FRET efficiency between two fluophores in IL3 and C-tail of α2A-adrenoceptor, which is translated within milliseconds in reduced G protein activation by the α2A-adrenoceptor protomer (Figure 4A). Well-designed molecular engineering also revealed functional allosterism in dopamine D2 receptor homodimers (Han et al., 2009). To this end, the D2 receptor was fused without a linker to the chimeric G protein Gαqi5. This fusion protein (i.e. D2–Gαqi5) was non-functional when expressed on its own; however, co-expression of wild-type D2 receptor resulted in agonist-induced coupling of the latter to the Gαqi5 protein of the non-functional D2–Gαqi5 by forming dimers. In contrast, binding- or coupling-deficient D2 receptor mutants were unable to signal through the fused Gαqi5 when co-expressed with D2–Gαqi5. Moreover, also the capacity of the non-functional D2–Gαqi5 to interact with G proteins appeared to be essential for dimer-induced signalling. Interestingly, this D2 receptor dimer is fully activated by agonist binding to one protomer, confirming the asymmetric nature between dimer protomers. In fact, binding of an additional agonist or inverse agonist to the second protomer disrupted or increased dimer signalling respectively. Importantly, as an ‘artificial’ Gαqi5-mediated response is measured, observed dimer signalling must result from physical interactions between the protomers and G protein rather than from downstream crosstalk in signalling pathways. Indeed, differential cross-linking of D2 dimers in inverse agonist versus agonist-bound state suggests that conformational changes at the dimer interface is part of the receptor activation mechanism (Guo et al., 2005).

Figure 4.

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are talking hand-in-hand. (A) Agonist (red triangle)-induced conformational change in one (white) protomer is transferred to the second agonist (blue triangle)-occupied protomer, resulting in a changed conformation as detected by decreased intramolecular fluorescence resonance energy transfer. (B) Negative binding cooperativity between ligand on a GPCR heteromer. (C) Positive binding cooperativity between ligands on a GPCR heteromer. (D) Change in G protein coupling and downstream signalling upon heteromerization of the Gs-coupled D1 and the Gi/o-coupled D2 receptor, resulting in Gq-mediated Ca2+ signalling.

Similar to the engineered D2 receptor dimer with the single fused G protein, the leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 homodimer only couples to one heterotrimeric G protein at a time (Baneres and Parello, 2003). Agonist-induced activation of one of the BLT1 protomers is sufficient to promote G protein coupling and activation (Damian et al., 2006). Moreover, fluorescence spectroscopy analysis revealed that the other protomer adopts a distinct conformation than the activated protomer. However, this difference in protomer conformation was not observed in the absence of G proteins, suggesting that the G protein confers asymmetry to the BLT1 homodimer by restricting conformational changes in the second protomer.

Intermolecular crosstalk within receptor oligomers can result in allosterism between the orthosteric binding pockets of the individual protomers. Negative binding cooperativity has been observed for both GPCR homomers and heteromers using equilibrium binding and/or radioligand dissociation experiments (Springael et al., 2007). The latter is in particular interesting in light of GPCR crosstalk as mutual exclusive binding of one ligand to receptor heteromers results in a decreased responsiveness to the ligand of the other protomer (Figure 4B). Detection of negative binding cooperativity using equilibrium binding assays on membrane preparations co-expressing the receptors of interest has been questioned on the merit that G protein coupling to agonist-occupied receptors might be irreversible in the absence of free GTP to substitute the released GDP (Chabre et al., 2009). G protein scavenging by the agonist-occupied GPCR may deplete a shared pool of G proteins from interacting with other (perhaps non-associated) receptors, often resulting in decreased apparent affinities of the latter receptors for their agonists (Chabre et al., 2009; Birdsall, 2010). This may be easily misinterpreted as being negative binding cooperativity between two interacting protomers. However, co-expression of additional G protein may shed light in this matter by preventing depletion (Nijmeijer et al., 2010). Moreover, this proposed G protein-stealing hypothesis is not compatible with an increased dissociation rate of pre-bound agonist from one protomer upon agonist binding to the second protomer if there is negative cooperativity between the two binding sites. For instance, negative cooperative has been detected within CCR2, CCR5 and CXCR4 heteromeric complexes in both recombinant cells and native immune cells (El-Asmar et al., 2005; Springael et al., 2006; Sohy et al., 2007; 2009;). Cross-competition was detected between their cognate chemokines in equilibrium binding experiments on both membrane preparations and intact cells, with the extent of cross-inhibition corresponding roughly to the anticipated proportion of cognate receptors involved in heteromeric complexes. Acceleration of each other's dissociation rates in ‘infinite’ tracer dilution experiments confirmed the allosteric nature of this cross-inhibition rather than steric hindrance between these chemokines at the extracellular surface of the receptor heteromers. Interestingly, negative cooperativity within CCR2, CCR5 and CXCR4 heteromers is not limited to agonist (i.e. chemokines) but was also observed for low molecular weight antagonists of these receptors, suggesting that downstream signalling is not per se involved in this cross-regulation. Moreover, cross-inhibition of chemokine-induced immune cell recruitment both in vitro and in vivo by antagonists that interact with other chemokine receptor subtypes within the heteromer, confirmed the functional relevance of the observed binding cooperativity between these receptors. Interestingly, D2 receptor homodimers and vasopressin V1A/oxytocin (OT) receptor heterodimers were readily detected by trFRET upon binding of fluophore-conjugated antagonists to each of the protomers, whereas incubation of similar samples with an excess of fluorescent agonist resulted in very weak FRET signals (Albizu et al., 2010). Similar discrepancy in cooperativity between agonists and antagonists was observed in radioligand binding experiments on membranes that express V1A, oxytocin or D2 receptors (Albizu et al., 2006; Kara et al., 2010). Hence, the apparent absence of binding cooperativity between antagonists on V1A, OT or D2 receptor homomers and/or heteromers is different from the observations in chemokine receptor heteromers (Sohy et al., 2009). Interestingly, opposite binding cooperativity was observed within 5-HT2A/mGlu2 receptor heteromers in mouse somatosensory cortex membranes (Gonzalez-Maeso et al., 2008). The mGluR2 agonist LY379268 increases the affinity of hallucinogenic agonists such as 1-(2,5)-dimethoxy-4-indophenyl)-2-aminopropane (DOI) for the 5-HT2A receptor, whereas DOI decreases the affinity of LY379268 for the mGluR2. On the contrary, however, the sensitized Gi/o signalling of 5-HT2A/mGlu2 receptor heteromers in response to hallucinogenic 5-HT2A receptor agonists was reversed upon activation of mGluR2 by LY379268.

Besides intermolecular inhibitory crosstalk between protomer binding pockets, also specific interactions between their intracellular domains may affect the ligand binding properties of GPCR heteromers. For example, the orphan receptor GPR50 forms heteromers with the Gi/o-coupled melatonin receptors MT1 and MT2 (Levoye et al., 2006a). GPR50 inhibited melatonin binding to the associated MT1 but not MT2 protomer, suggesting that downstream G protein stealing per se was not the underlying mode of action. Inhibition of MT1 protomer function appeared to be attributed to the long C-tail of GPR50, which apparently interact differently with the MT1 as compared with MT2 protomer, thereby hindering G protein coupling to the MT1 protomer (Levoye et al., 2006a).

Stimulation of the δOR/Mas-related GPCR member X (MRGPRX1, a.k.a. SNSR-4) heteromer with selective δOR or MRGPRX1 agonists triggered Gi/o or Gq signalling respectively. However, simultaneous binding of selective δOR and MRGPRX1 agonists to the δOR/ MRGPRX1 heteromer led exclusively to Gq activation, suggesting a dominant negative effect of the activated MRGPRX1 protomer on δOR-specific signalling (Breit et al., 2006).

On the other hand, agonist binding and activation of both receptor protomers is required for efficient signalling of some other homomers and heteromers. Although a single glutamate molecule is sufficient to promote mGlu5 homodimer signalling, the binding of two glutamate molecules per homodimer is required for full activation (Kniazeff et al., 2004). Heteromerization of the δ- with κ-opioid receptor (δOR and κOR respectively) resulted in a loss of binding affinity for either δOR- or κOR-selective ligands, whereas partially selective ligands preserved or increased their affinity for the δOR–κOR heteromer (Jordan and Devi, 1999). However, positive binding cooperativity was observed when either δOR- and κOR-selective agonists or a combination of selective antagonists were incubated with a non-selective radiolabelled antagonist and δOR–κOR heteromer-expressing membranes, resulting in at least a 50-fold increase in affinity (Figure 4C). Surprisingly, only a 10- to 20-fold potentiation in signalling was seen in cells co-expressing δOR and κOR upon co-stimulation with the selective agonists. Even though intermolecular interactions between δOR and κOR are apparent and give rise to a distinctive ligand binding profile, the exact quality and quantity of allosterism within this heteromer seems puzzling (Birdsall, 2010). Interestingly, no positive cooperativity was observed between δOR-selective antagonist and κOR-selective agonist on δOR–κOR heteromers. In contrast, δOR-selective antagonists enhance agonist binding and signalling to the µOR protomer within δOR–µOR heteromers (Gomes et al., 2000). Activated δOR or µOR preferentially activates Gαi proteins as determined by 35S-GTPγS incorporation in selectively immunoprecipitated G proteins, whereas activated δOR–µOR heteromers interact selectively with Gαz proteins (Fan et al., 2005). In addition and in contrast to its homomeric constituents, the δOR–µOR heteromer constitutively recruits β-arrestin2 and is primed to signal through non-G protein-activated pathways (Rozenfeld and Devi, 2007). Activation of the Gi/o-coupled dopamine D3 receptor increases the agonist affinity of Gs-coupled D1 receptors. This positive binding cooperativity within D1–D3 receptor heteromers results in increased Gs-mediated locomotor activity, which can be inhibited by D3 receptor antagonists (Marcellino et al., 2008). On the other hand, heteromerization of the D1 receptor with the Gi/o-coupled histamine H3 receptor triggered Gi-dependent but Gs-independent MAPK signalling pathway activation in response to dopaminergic or histaminergic agonists, which could be (cross-)blocked by selective antagonists acting at either of the two protomers (Ferrada et al., 2009). This acquired capacity of histaminergic agonists to induce MAPK signalling through the H3R was strictly dependent on the presence of the D1 receptor. The D1 and D2 receptors activate of Gs and Gi/o proteins, respectively, resulting in an opposite regulation of cAMP production by adenylyl cyclase (Figure 4D) (Lee et al., 2004). However, D1–D2 receptor heteromers can couple to Gq/11 proteins upon agonist binding to both protomers, resulting in intracellular calcium release from the ER and subsequent activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIα (CaMKIIα) (Lee et al., 2004; Rashid et al., 2007). Importantly, the Gq/11 inhibitor YM254890 could fully inhibit D1–D2 receptor heteromer-induced intracellular Ca2+ mobilization, revealing that Gq/11 coupling rather than downstream crosstalk initiates this signalling pathway. D1–D2 receptor heteromers have been detected in various brain regions and their capacity to activate CaMKIIα can be inhibited by pre-administration of D1 or D2 receptor antagonists, and is disrupted in D1 or D2 receptor knockout mice (Rashid et al., 2007). D1–D2 receptor heteromer signalling has been linked to synaptic plasticity as well as behavioural sensitization to psychostimulants, while reduced D1–D2 receptor heteromer activity has been linked to schizophrenia as disturbed calcium homeostasis is thought to underlie this neuropsychiatric disease (Rashid et al., 2007). Hence, the intracellular surface of GPCR heteromers has likely a distinctive conformation as compared with their constituent mono- and/or homo-oligomers, which may result in the recognition of different signalling partners.

Agonist-induced cross-linking of AT1R homodimers by intracellular factor XIIIA transglutaminase increased Gq/11 activation and the formation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphates as compared with non-cross-linked AT1R. Noteworthy, factor XIIIA activity and cross-linked AT1R homodimers were increased in hypertensive patients, resulting in enhanced monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelial cells (AbdAlla et al., 2004). On the other hand, monomers of purified rhodopsin, µOR, neurotensin receptor NTS1, β2-adrenoceptor and leukotriene B4 receptor BLT2, reconstituted in nanodiscs or liposomes were shown to bind and activate G proteins and/or (β-)arrestin equally or often more efficiently than their respective homomers (White et al., 2007; Whorton et al., 2007; 2008; Kuszak et al., 2009; Arcemisbehere et al., 2010; Tsukamoto et al., 2010). In line, higher order GABAB receptor oligomers (i.e. homomers of the obligate heterodimer GABAB1/GABAB2) had a lower efficacy to activate G proteins than non-associated GABAB receptors (Maurel et al., 2008). Hence, homomerization may control cellular responsiveness by limiting G protein coupling efficacy when receptor levels and consequently homomer numbers are elevated to avoid hyperstimulation.

In short, convincing evidence shows intramolecular communication within GPCR oligomers, which may result in both positive and negative ligand binding cooperativity, as well as differential coupling to G protein subtypes and/or β-arrestins in comparison with their monomeric counterparts.

Do GPCRs (oligomers) shout from a distance?

Crosstalk between co-expressed GPCRs is not limited to physical receptor–receptor interactions, but can also occur along intracellular signalling pathways that may be interconnected in integrative networks or share limiting components. Consequently, it may be difficult to distinguish whether one receptor affects the signalling properties of an associated GPCR causally due to oligomerization or perhaps due to downstream crosstalk in signalling pathways.

G protein-coupled receptors can dampen each other's agonist responsiveness if they are competing for the same G protein subtype. This crosstalk becomes particularly apparent when one of the competing GPCRs is constitutive active and effectively depletes the cellular pool of available G proteins. For example, cannabinoid CB1 and µ-opioid receptors activate predominantly Gαi/o-coupled signalling pathways and are co-expressed in individual neurons in the striatum, caudate nucleus and dorsal horn. However, the CB1 receptor constitutively inhibits agonist-induced µOR signalling, which can be restored by co-incubation with a CB1 receptor inverse agonist or silencing of the ligand-independent CB1 receptor signalling by site-directed mutagenesis (Canals and Milligan, 2008). Although BRET experiments suggested that CB1 receptor and µOR exist as heteromers, microscopy studies revealed distinct subcellular localization patterns of both GPCR proteins (Canals and Milligan, 2008). The latter implies that CB1 receptor and µOR are not assembled as heteromers and cross-regulation of µOR signalling by the constitutive active CB1 receptor is downstream, presumably via G protein scavenging.

The Epstein-Barr virus-encoded GPCR BILF1 forms heteromers with the human chemokine receptor CXCR4 (Vischer et al., 2008; Nijmeijer et al., 2010). The constitutive active BILF1 also inhibits binding of CXCL12 to CXCR4, whereas a BILF1 mutant, deficient in G protein coupling had a much lesser effect on CXCR4 functioning. Importantly, CXCL12 binding to CXCR4 is highly dependent on the availability of Gαi1 proteins, and co-expression of additional Gαi1 proteins with BILF1 and CXCR4 restored normal functioning of the latter (Nijmeijer et al., 2010). Although intermolecular inhibition of CXCR4 by BILF1 within a heteromeric complex cannot be ruled out, the rescue of CXCR4 functioning by additional G proteins supports the hypothesis that BILF1 inhibits co-expressed Gi/o-coupled GPCRs by constitutive scavenging of a shared pool of available Gi/o proteins.

In addition, GPCRs can impair each other agonist's responsiveness by activating second messenger-dependent protein kinases A or C. These protein kinases can phosphorylate both inactive and active receptors but also G proteins, resulting in reduced responsiveness of multiple GPCR subtypes to their cognate agonists (Kelly et al., 2008; Chu et al., 2010).

Although examples of Gi- and Gq-coupled receptors that modulate each other's activity through heteromerization are available, compelling evidence for downstream crosstalk between these (constitutively active) GPCRs have been reported as well. Constitutive signalling of the Gq/11-coupled histamine H1 receptor is increased in cells co-expressing Gi/o-coupled serotonin 5-HT1B, adenosine A1, or M2 muscarinic receptors, in a Pertussis toxin-sensitive manner (Bakker et al., 2004a). This H1R-mediated signalling can be further increased by stimulation with agonists of the co-expressed receptors. On the other hand, the 5-HT1B receptor inverse agonist inhibited the Pertussis toxin-sensitive increase in signalling in H1R and 5-HT1B receptor co-expressing cells, whereas the H1R inverse agonist mepyramine inhibited all signalling. Importantly, GPCR-independent stimulation of Gi/o proteins by using mastoparan-7 resulted in a similar potentiation of H1R signalling indicating unambiguously that the observed crosstalk is on the level of intracellular signalling pathways rather than through receptor heteromerization (Bakker et al., 2004a). Similar downstream crosstalk mechanism was observed between the constitutively active Gq/11-coupled human cytomegalovirus-encoded receptor US28 and Gi/o-coupled CCR1 chemokine receptors, the constitutive active Gq/11-coupled mGlu1a and Gi/o-coupled GABAB receptor (Rives et al., 2009), and might also apply for the sensitization of Gq/11-coupled orexin-1 receptor by the constitutively active Gi/o-coupled CB1 receptor in a Pertussis toxin-sensitive manner, which was suggested by the authors to be a direct consequence of orexin 1/CB1 receptor heteromerization (Hilairet et al., 2003). Heteromerization between CB1 and orexin-1 receptor was indeed confirmed in distinct cells and was accompanied with a change in cellular distribution of the orexin-1 receptor (Ellis et al., 2006). However, in this study CB1 had only marginal effect on agonist-induced orexin-1 receptor signalling, which was explained as a difference in cellular background (Ellis et al., 2006).

Conclusions

Increasing evidence suggest that GPCR oligomerization is essential for cell surface targeting of GPCRs. Whether GPCRs keep on walking hand-in-hand on the cell surface is currently under investigation. Some GPCRs appear to form stable oligomeric complexes, while other spend most of their time wandering around alone. In fact, purified and reconstituted class A GPCR monomers are fully capable to mediate agonist-induced signalling. On the other hand, compelling evidence is available that GPCR oligomers do talk differently hand-in-hand than when they are on their own, for example by shifting from G protein class or from G protein to β-arrestin coupling. However, apparent crosstalk between GPCRs may as well originate more distal from GPCRs by interacting or limiting intracellular signalling network constituents, which may actually affect GPCR properties like agonist binding. Showing that physical GPCR interactions are absolutely required for unique agonist-induced signalling, by actually disrupting them, might therefore be helpful to unambiguously distinguish crosstalk within GPCR heteromers from crosstalk events (far) below these heteromers.

Acknowledgments

HFV, SN and RL are supported by the EU-KP7 COST program BM0806 (Histamine H4 receptor network). Dutch Top Institute Pharma Project D1-105 supports AOW. Finally, we apologize to all authors whose significant contributions to the field of GPCR oligomerization and crosstalk could not be mentioned in this review owing to space limitation.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BRET

bioluminescence resonance energy transfer

- CaMKIIα

calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIα

- EL

extracellular loop

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FRAP

fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- GABA

γ-amino butyric acid

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- GRK

GPCR kinase

- IL

intracellular loop

- NTED

N-terminal extracellular domain

- PFC

protein-fragment complementation

- RASSL

receptor activated solely by synthetic ligands

- RET

resonance energy transfer

- Rluc

Renilla reniformis luciferase

- TM

transmembrane

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Teaching Materials; Figs 1–4 as PowerPoint slide.

References

- AbdAlla S, Lother H, Langer A, el Faramawy Y, Quitterer U. Factor XIIIA transglutaminase crosslinks AT1 receptor dimers of monocytes at the onset of atherosclerosis. Cell. 2004;119:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achour L, Labbe-Jullie C, Scott MG, Marullo S. An escort for GPCRs: implications for regulation of receptor density at the cell surface. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albizu L, Balestre MN, Breton C, Pin JP, Manning M, Mouillac B, et al. Probing the existence of G protein-coupled receptor dimers by positive and negative ligand-dependent cooperative binding. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1783–1791. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albizu L, Cottet M, Kralikova M, Stoev S, Seyer R, Brabet I, et al. Time-resolved FRET between GPCR ligands reveals oligomers in native tissues. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:587–594. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Curto E, Ward RJ, Pediani JD, Milligan G. Ligand regulation of the quaternary organization of cell surface M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors analyzed by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) imaging and homogeneous time-resolved FRET. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:23318–23330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.122184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angers S, Salahpour A, Joly E, Hilairet S, Chelsky D, Dennis M, et al. Detection of beta 2-adrenergic receptor dimerization in living cells using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3684–3689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060590697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcemisbehere L, Sen T, Boudier L, Balestre MN, Gaibelet G, Detouillon E, et al. Leukotriene BLT2 receptor monomers activate the G(i2) GTP-binding protein more efficiently than dimers. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:6337–6347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.083477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker RA, Casarosa P, Timmerman H, Smit MJ, Leurs R. Constitutively active Gq/11-coupled receptors enable signaling by co-expressed Gi/o-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem. 2004a;279:5152–5161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309200200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker RA, Dees G, Carrillo JJ, Booth RG, Lopez-Gimenez JF, Milligan G, et al. Domain swapping in the human histamine H1 receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004b;311:131–138. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.067041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker RA, Lozada AF, van Marle A, Shenton FC, Drutel G, Karlstedt K, et al. Discovery of naturally occurring splice variants of the rat histamine H3 receptor that act as dominant-negative isoforms. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1194–1206. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.019299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baneres JL, Parello J. Structure-based analysis of GPCR function: evidence for a novel pentameric assembly between the dimeric leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 and the G-protein. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:815–829. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayburt TH, Leitz AJ, Xie G, Oprian DD, Sligar SG. Transducin activation by nanoscale lipid bilayers containing one and two rhodopsins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14875–14881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701433200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayburt TH, Vishnivetskiy SA, McLean MA, Morizumi T, Huang CC, Tesmer JJ, et al. Monomeric rhodopsin is sufficient for normal rhodopsin kinase (GRK1) phosphorylation and arrestin-1 binding. J Biol Chem. 2010;286:1420–1428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo I, Yu Hsu S, Rauch R, Kowalski HW, Hsueh AJ. Signaling receptome: a genomic and evolutionary perspective of plasma membrane receptors involved in signal transduction. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:RE9. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.187.re9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier V, Lagace M, Bichet DG, Bouvier M. Pharmacological chaperones: potential treatment for conformational diseases. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birdsall NJ. Class A GPCR heterodimers: evidence from binding studies. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:499–508. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borroto-Escuela DO, Marcellino D, Narvaez M, Flajolet M, Heintz N, Agnati L, et al. A serine point mutation in the adenosine A2AR C-terminal tail reduces receptor heteromerization and allosteric modulation of the dopamine D2R. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;394:222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier M. Oligomerization of G-protein-coupled transmitter receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:274–286. doi: 10.1038/35067575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breit A, Gagnidze K, Devi LA, Lagace M, Bouvier M. Simultaneous activation of the delta opioid receptor (deltaOR)/sensory neuron-specific receptor-4 (SNSR-4) hetero-oligomer by the mixed bivalent agonist bovine adrenal medulla peptide 22 activates SNSR-4 but inhibits deltaOR signaling. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:686–696. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.022897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock C, Boudier L, Maurel D, Blahos J, Pin JP. Assembly-dependent surface targeting of the heterodimeric GABAB Receptor is controlled by COPI but not 14-3-3. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5572–5578. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-05-0400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello N, Gandia J, Bertarelli DC, Watanabe M, Lluis C, Franco R, et al. Metabotropic glutamate type 5, dopamine D2 and adenosine A2a receptors form higher-order oligomers in living cells. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1497–1507. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calebiro D, de Filippis T, Lucchi S, Covino C, Panigone S, Beck-Peccoz P, et al. Intracellular entrapment of wild-type TSH receptor by oligomerization with mutants linked to dominant TSH resistance. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2991–3002. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canals M, Milligan G. Constitutive activity of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor regulates the function of co-expressed Mu opioid receptors. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11424–11434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canals M, Lopez-Gimenez JF, Milligan G. Cell surface delivery and structural re-organization by pharmacological chaperones of an oligomerization-defective alpha(1b)-adrenoceptor mutant demonstrates membrane targeting of GPCR oligomers. Biochem J. 2009;417:161–172. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriba P, Navarro G, Ciruela F, Ferre S, Casado V, Agnati L, et al. Detection of heteromerization of more than two proteins by sequential BRET-FRET. Nat Methods. 2008;5:727–733. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabre M, Deterre P, Antonny B. The apparent cooperativity of some GPCRs does not necessarily imply dimerization. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu J, Zheng H, Zhang Y, Loh HH, Law PY. Agonist-dependent mu-opioid receptor signaling can lead to heterologous desensitization. Cell Signal. 2010;22:684–696. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciruela F, Vilardaga JP, Fernandez-Duenas V. Lighting up multiprotein complexes: lessons from GPCR oligomerization. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coge F, Guenin SP, Renouard-Try A, Rique H, Ouvry C, Fabry N, et al. Truncated isoforms inhibit [3H]prazosin binding and cellular trafficking of native human alpha1A-adrenoceptors. Biochem J. 1999;343(Pt 1):231–239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damak S, Rong M, Yasumatsu K, Kokrashvili Z, Varadarajan V, Zou S, et al. Detection of sweet and umami taste in the absence of taste receptor T1r3. Science. 2003;301:850–853. doi: 10.1126/science.1087155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damian M, Martin A, Mesnier D, Pin JP, Baneres JL. Asymmetric conformational changes in a GPCR dimer controlled by G-proteins. EMBO J. 2006;25:5693–5702. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsam RT, Gutkind JS. G-protein-coupled receptors and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:79–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsch S, Klotz KN, Engelhardt S, Lohse MJ, Bunemann M. Analysis of receptor oligomerization by FRAP microscopy. Nat Methods. 2009;6:225–230. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthey B, Caudron S, Perroy J, Bettler B, Fagni L, Pin JP, et al. A single subunit (GB2) is required for G-protein activation by the heterodimeric GABA(B) receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3236–3241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108900200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Asmar L, Springael JY, Ballet S, Andrieu EU, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Evidence for negative binding cooperativity within CCR5-CCR2b heterodimers. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:460–469. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.003624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J, Pediani JD, Canals M, Milasta S, Milligan G. Orexin-1 receptor-cannabinoid CB1 receptor heterodimerization results in both ligand-dependent and -independent coordinated alterations of receptor localization and function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38812–38824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602494200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan QR, Hendrickson WA. Structure of human follicle-stimulating hormone in complex with its receptor. Nature. 2005;433:269–277. doi: 10.1038/nature03206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan T, Varghese G, Nguyen T, Tse R, O'Dowd BF, George SR. A role for the distal carboxyl tails in generating the novel pharmacology and G protein activation profile of mu and delta opioid receptor hetero-oligomers. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38478–38488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505644200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrada C, Moreno E, Casado V, Bongers G, Cortes A, Mallol J, et al. Marked changes in signal transduction upon heteromerization of dopamine D1 and histamine H3 receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:64–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre S, Franco R. Oligomerization of G-protein-coupled receptors: a reality. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre S, Baler R, Bouvier M, Caron MG, Devi LA, Durroux T, et al. Building a new conceptual framework for receptor heteromers. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:131–134. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0309-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca JM, Lambert NA. Instability of a class a G protein-coupled receptor oligomer interface. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:1296–1299. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.053876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung JJ, Deupi X, Pardo L, Yao XJ, Velez-Ruiz GA, Devree BT, et al. Ligand-regulated oligomerization of beta(2)-adrenoceptors in a model lipid bilayer. EMBO J. 2009;28:3315–3328. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvez T, Duthey B, Kniazeff J, Blahos J, Rovelli G, Bettler B, et al. Allosteric interactions between GB1 and GB2 subunits are required for optimal GABA(B) receptor function. EMBO J. 2001;20:2152–2159. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandia J, Galino J, Amaral OB, Soriano A, Lluis C, Franco R, et al. Detection of higher-order G protein-coupled receptor oligomers by a combined BRET-BiFC technique. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2979–2984. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, Harikumar KG, Dong M, Lam PC, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A, et al. Functional importance of a structurally distinct homodimeric complex of the family B G protein-coupled secretin receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:264–274. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.055756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goin JC, Nathanson NM. Quantitative analysis of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor homo- and heterodimerization in live cells: regulation of receptor down-regulation by heterodimerization. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5416–5425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes I, Jordan BA, Gupta A, Trapaidze N, Nagy V, Devi LA. Heterodimerization of mu and delta opioid receptors: a role in opiate synergy. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-j0007.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Maeso J, Ang RL, Yuen T, Chan P, Weisstaub NV, Lopez-Gimenez JF, et al. Identification of a serotonin/glutamate receptor complex implicated in psychosis. Nature. 2008;452:93–97. doi: 10.1038/nature06612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Shi L, Filizola M, Weinstein H, Javitch JA. Crosstalk in G protein-coupled receptors: changes at the transmembrane homodimer interface determine activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17495–17500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508950102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Urizar E, Kralikova M, Mobarec JC, Shi L, Filizola M, et al. Dopamine D2 receptors form higher order oligomers at physiological expression levels. EMBO J. 2008;27:2293–2304. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV. GPCR monomers and oligomers: it takes all kinds. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hague C, Uberti MA, Chen Z, Hall RA, Minneman KP. Cell surface expression of alpha1D-adrenergic receptors is controlled by heterodimerization with alpha1B-adrenergic receptors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15541–15549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314014200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Moreira IS, Urizar E, Weinstein H, Javitch JA. Allosteric communication between protomers of dopamine class A GPCR dimers modulates activation. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:688–695. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson SM, Gurevich EV, Vishnivetskiy SA, Ahmed MR, Song X, Gurevich VV. Each rhodopsin molecule binds its own arrestin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3125–3128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610886104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada N, Yamada Y, Tsukiyama K, Yamada C, Nakamura Y, Mukai E, et al. A novel GIP receptor splice variant influences GIP sensitivity of pancreatic beta-cells in obese mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:E61–E68. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00358.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harikumar KG, Morfis MM, Lisenbee CS, Sexton PM, Miller LJ. Constitutive formation of oligomeric complexes between family B G protein-coupled vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and secretin receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:363–373. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.015776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havlickova M, Prezeau L, Duthey B, Bettler B, Pin JP, Blahos J. The intracellular loops of the GB2 subunit are crucial for G-protein coupling of the heteromeric gamma-aminobutyrate B receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:343–350. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert TE, Moffett S, Morello JP, Loisel TP, Bichet DG, Barret C, et al. A peptide derived from a beta(2)-adrenergic receptor transmembrane domain inhibits both receptor dimerization and activation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16384–16392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin CH. Dimerization of cell surface receptors in signal transduction. Cell. 1995;80:213–223. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hern JA, Baig AH, Mashanov GI, Birdsall B, Corrie JE, Lazareno S, et al. Formation and dissociation of M1 muscarinic receptor dimers seen by total internal reflection fluorescence imaging of single molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:2693–2698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907915107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilairet S, Bouaboula M, Carriere D, Le Fur G, Casellas P. Hypersensitization of the Orexin 1 receptor by the CB1 receptor: evidence for cross-talk blocked by the specific CB1 antagonist, SR141716. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23731–23737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji I, Lee C, Song Y, Conn PM, Ji TH. Cis- and trans-activation of hormone receptors: the LH receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:1299–1308. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.6.0852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji I, Lee C, Jeoung M, Koo Y, Sievert GA, Ji TH. Trans-activation of mutant follicle-stimulating hormone receptors selectively generates only one of two hormone signals. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:968–978. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KA, Borowsky B, Tamm JA, Craig DA, Durkin MM, Dai M, et al. GABA(B) receptors function as a heteromeric assembly of the subunits GABA(B)R1 and GABA(B)R2. Nature. 1998;396:674–679. doi: 10.1038/25348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan BA, Devi LA. G-protein-coupled receptor heterodimerization modulates receptor function. Nature. 1999;399:697–700. doi: 10.1038/21441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara E, Lin H, Strange PG. Co-operativity in agonist binding at the D2 dopamine receptor: evidence from agonist dissociation kinetics. J Neurochem. 2010;112:1442–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpa KD, Lin R, Kabbani N, Levenson R. The dopamine D3 receptor interacts with itself and the truncated D3 splice variant d3nf: D3-D3nf interaction causes mislocalization of D3 receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:677–683. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupmann K, Malitschek B, Schuler V, Heid J, Froestl W, Beck P, et al. GABA(B)-receptor subtypes assemble into functional heteromeric complexes. Nature. 1998;396:683–687. doi: 10.1038/25360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly E, Bailey CP, Henderson G. Agonist-selective mechanisms of GPCR desensitization. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl. 1):S379–S388. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khelashvili G, Dorff K, Shan J, Camacho-Artacho M, Skrabanek L, Vroling B, et al. GPCR-OKB: the G protein coupled receptor oligomer knowledge base. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1804–1805. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kniazeff J, Galvez T, Labesse G, Pin JP. No ligand binding in the GB2 subunit of the GABA(B) receptor is required for activation and allosteric interaction between the subunits. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7352–7361. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07352.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kniazeff J, Bessis AS, Maurel D, Ansanay H, Prezeau L, Pin JP. Closed state of both binding domains of homodimeric mGlu receptors is required for full activity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:706–713. doi: 10.1038/nsmb794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen K. Molecular mechanisms of ligand binding, signaling, and regulation within the superfamily of G-protein-coupled receptors: molecular modeling and mutagenesis approaches to receptor structure and function. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;103:21–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuszak AJ, Pitchiaya S, Anand JP, Mosberg HI, Walter NG, Sunahara RK. Purification and functional reconstitution of monomeric mu-opioid receptors: allosteric modulation of agonist binding by Gi2. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:26732–26741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagerstrom MC, Schioth HB. Structural diversity of G protein-coupled receptors and significance for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:339–357. doi: 10.1038/nrd2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Ji I, Ryu K, Song Y, Conn PM, Ji TH. Two defective heterozygous luteinizing hormone receptors can rescue hormone action. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15795–15800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111818200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SP, So CH, Rashid AJ, Varghese G, Cheng R, Lanca AJ, et al. Dopamine D1 and D2 receptor Co-activation generates a novel phospholipase C-mediated calcium signal. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35671–35678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. Transduction of receptor signals by beta-arrestins. Science. 2005;308:512–517. doi: 10.1126/science.1109237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levoye A, Dam J, Ayoub MA, Guillaume JL, Couturier C, Delagrange P, et al. The orphan GPR50 receptor specifically inhibits MT1 melatonin receptor function through heterodimerization. EMBO J. 2006a;25:3012–3023. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levoye A, Dam J, Ayoub MA, Guillaume JL, Jockers R. Do orphan G-protein-coupled receptors have ligand-independent functions? New insights from receptor heterodimers. EMBO Rep. 2006b;7:1094–1098. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limbird LE, Meyts PD, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-adrenergic receptors: evidence for negative cooperativity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;64:1160–1168. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(75)90815-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Gimenez JF, Canals M, Pediani JD, Milligan G. The alpha1b-adrenoceptor exists as a higher-order oligomer: effective oligomerization is required for receptor maturation, surface delivery, and function. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:1015–1029. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.033035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasiewicz S, Faron-Gorecka A, Dobrucki J, Polit A, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M. Studies on the role of the receptor protein motifs possibly involved in electrostatic interactions on the dopamine D1 and D2 receptor oligomerization. FEBS J. 2009;276:760–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasiewicz S, Polit A, Kedracka-Krok S, Wedzony K, Mackowiak M, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M. Hetero-dimerization of serotonin 5-HT(2A) and dopamine D(2) receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:1347–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggio R, Vogel Z, Wess J. Coexpression studies with mutant muscarinic/adrenergic receptors provide evidence for intermolecular ‘cross-talk’ between G-protein-linked receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3103–3107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcellino D, Ferre S, Casado V, Cortes A, Le Foll B, Mazzola C, et al. Identification of dopamine D1-D3 receptor heteromers. Indications for a role of synergistic D1-D3 receptor interactions in the striatum. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26016–26025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710349200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margeta-Mitrovic M, Jan YN, Jan LY. A trafficking checkpoint controls GABA(B) receptor heterodimerization. Neuron. 2000;27:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marianayagam NJ, Sunde M, Matthews JM. The power of two: protein dimerization in biology. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel D, Kniazeff J, Mathis G, Trinquet E, Pin JP, Ansanay H. Cell surface detection of membrane protein interaction with homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer technology. Anal Biochem. 2004;329:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel D, Comps-Agrar L, Brock C, Rives ML, Bourrier E, Ayoub MA, et al. Cell-surface protein-protein interaction analysis with time-resolved FRET and snap-tag technologies: application to GPCR oligomerization. Nat Methods. 2008;5:561–567. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier JF, Salahpour A, Angers S, Breit A, Bouvier M. Quantitative assessment of beta 1- and beta 2-adrenergic receptor homo- and heterodimerization by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44925–44931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205767200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michnick SW, Ear PH, Manderson EN, Remy I, Stefan E. Universal strategies in research and drug discovery based on protein-fragment complementation assays. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:569–582. doi: 10.1038/nrd2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]