Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Capsaicin, an agonist of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) channels, is pro-nociceptive in the periphery but is anti-nociceptive when administered into the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray (vlPAG), a midbrain region for initiating descending pain inhibition. Here, we investigated how activation of TRPV1 channels in the vlPAG leads to anti-nociception.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

We examined synaptic transmission and neuronal activity using whole-cell recordings in vlPAG slices in vitro and hot-plate nociceptive responses in rats after drug microinjection into the vlPAG in vivo.

KEY RESULTS

Capsaicin (1–10 µM) depressed evoked GABAergic inhibitory postsynaptic currents (eIPSCs) in vlPAG slices presynaptically, while increasing miniature excitatory PSC frequency. Capsaicin-induced eIPSC depression was antagonized by cannabinoid CB1 and metabotropic glutamate (mGlu5) receptor antagonists, and prevented by inhibiting diacylglycerol lipase (DAGL), which converts DAG into 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), an endocannabinoid. Capsaicin induced membrane depolarization in 2/3 neurons recorded but, overall, increased neuronal firings by increasing evoked postsynaptic potentials. Intra-vlPAG capsaicin reduced hot-plate responses in rats, effects blocked by CB1 and mGlu receptor antagonists. Effects of capsaicin were antagonized by SB 366791, a TRPV1 channel antagonist.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Capsaicin activated TRPV1s on glutamatergic terminals to release glutamate which activated postsynaptic mGlu5 receptors, yielding 2-AG from DAG by DAGL hydrolysis. 2-AG induces retrograde inhibition (disinhibition) of GABA release via presynaptic CB1 receptors. This disinhibition in the vlPAG leads to anti-nociception by activating the descending pain inhibitory pathway. This is a novel TRPV1 channel-mediated anti-nociceptive mechanism in the brain and a new interaction between vanilloid and endocannabinoid systems.

Keywords: capsaicin, transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 channels, metabotropic glutamate receptors, endocannabinoids, CB1 cannabinoid receptors, periaqueductal gray, pain, 2-arachidonoylglycerol

Introduction

The transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 channel (TRPV1), also known as the vanilloid receptor (channel and receptor nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2009), is a non-selective cation channel, originally described in peripheral sensory neurons (Caterina et al., 1997). These channels can be activated by capsaicin, resiniferatoxin and several endogenous compounds (‘endovanilloids’), such as anandamide (Zygmunt et al., 1999), N-arachidonyldopamine (Huang et al., 2002), 12-(S) hydroperoxy-eicosatetraenoic acid (12-(S)-HPETE) (Hwang et al., 2000) and octadecadienoids (Flores and Vasko, 2010). Immunohistochemical and autoradiographic studies have confirmed TRPV1 channel expression in several brain regions including the substantia nigra, ventral medulla, locus coeruleus, hypothalamus, ventral tegmental area (Mezey et al., 2000) and periaqueductal gray (PAG) (Roberts et al., 2004; Cristino et al., 2006), suggesting that TRPV1 channels are involved in thermal, motor, anxiety, cardiovascular and pain regulation (Steenland et al., 2006; Starowicz et al., 2008; Kauer and Gibson, 2009).

Capsaicin is pro-nociceptive in the periphery through peripheral TRPV1 channels, but it is anti-nociceptive when given by microinjection into the ventrolateral (Maione et al., 2006; Starowicz et al., 2007) or dorsolateral (Palazzo et al., 2001) area of the PAG, a midbrain region involved in supraspinal pain regulation. Activation of the PAG produces analgesia (Reynolds, 1969) through activating the downstream rostroventral medulla (RVM), which sends inhibitory projections to the spinal dorsal horn (Millan, 2002). This PAG–RVM–spinal dorsal horn circuit constitutes an endogenous descending pain inhibitory pathway. Depending on the changes (increase, decrease or no change) in neuronal activity upon nociceptive stimulation, the neurons in the RVM can be divided into ON, OFF and neutral cells (Heinricher et al., 2009). Starowicz et al. (2007) found that capsaicin, when injected into the ventrolateral PAG (vlPAG), increased the glutamate level and OFF cell activity in the RVM, suggesting that capsaicin excites the PAG to activate the descending pain inhibition.

How capsaicin excites the PAG to produce anti-nociception remains unclear, although several studies have been reported (Palazzo et al., 2002; Maione et al., 2006; Starowicz et al., 2007; Xing and Li, 2007). Capsaicin facilitates glutamate release in the PAG (Xing and Li, 2007), and its anti-nociceptive effect in the PAG was blocked by group I metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptor antagonists (Palazzo et al., 2001). Activation of postsynaptic Gq-protein coupled receptors (GqPCRs), including group I mGlu receptors, has been reported to induce phospholipid hydrolysis by phospholipase C (PLC) to yield diacylglycerol (DAG), which can be converted by DAG lipase (DAGL) into 2-arachidonolyglycerol (2-AG), an endocannabinoid. 2-AG diffuses retrogradely to activate presynaptic cannabinoid CB1 receptors and inhibit transmitter release in several brain regions, including the PAG (Drew et al., 2008; Drew et al., 2009; Kano et al., 2009; Mitchell et al., 2009) and the spinal cord (Nyilas et al., 2009). The PAG activity is largely regulated by intrinsic GABAergic tone (Behbehani et al., 1990); therefore, inhibition of this GABAergic tone (disinhibition) in the PAG can lead to analgesia. In this study, we used both electrophysiological and behavioural approaches to validate a hypothesis that activation of TRPV1 channels by capsaicin can excite the vlPAG to produce anti-nociception via facilitating presynaptic release of glutamate, which then activates postsynaptic mGlu receptor-mediated 2-AG retrograde disinhibition via the PLC-DAGL enzymic cascade.

Methods

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of College of Medicine, National Taiwan University.

Electrophysiological study

Dissection of PAG slices

Coronal midbrain slices (300 µm) containing the PAG were dissected from Wistar rats (P9–P18), as described previously (Liao et al., 2009). Isolated slices were equilibrated in artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF) at room temperature for at least 1 h before recording. The aCSF solution consisted of (mM): NaCl 117, KCl 4.5, CaCl2 2.5, MgCl2 1.2, NaH2PO4 1.2, NaHCO3 25 and dextrose 11.4, and were oxygenated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (pH 7.4; osmolarity: 290–295 mOsm). After equilibrium, one slice was placed in a submerged recording chamber and perfused with aCSF at 3.0 mL·min−1.

Visualized patch-clamp recordings

Visualized whole cell patch-clamp recordings were performed under a stage-fixed upright IR-DIC microscope (BX51WI, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 40× water-immersion objective. The microelectrode resistance was 4–8 MΩ when filled with the internal solution. The internal solution consisting of (mM): Cs+ gluconate 110, CaCl2 0.5, TEA-Cl 5, BAPTA 5, HEPES 5, MgATP 5, GTP Tris 0.33 and QX314Br 5 (pH = 7.3, liquid junction potential: −14.6 mV) was used in the voltage clamp mode for recording evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (eIPSCs), evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (eEPSCs), miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) and miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs), and the solution containing (mM): K+ gluconate 125, KCl 5, CaCl2 0.5, BAPTA 5, HEPES 10, MgATP 5 and GTP Tris 0.33 (pH = 7.3, liquid junction potential: −11.4 mV) was used in the current clamp mode for recording evoked postsynaptic potentials (ePSPs) and membrane potentials. Liquid junction potentials have been corrected.

Evoked IPSCs, EPSCs and PSPs

IPSCs, EPSCs and PSPs were evoked at 0.05 Hz by square pulses (10–30 V, 150 µs) from a Grass stimulator (Grass Telefactor, West Warwick, RI, USA) through a 50 µm bipolar concentric electrode (Frederick Haer & Co, Bowdoinham, ME, USA), which was placed 50–250 µm away from the recording electrode (Figure 1G). Evoked IPSCs were recorded at 0 mV in the presence of 2 mM kynurenic acid, a blocker of ionotropic glutamate receptors, including AMPA, kainate and NMDA receptors (Stone, 1993). Evoked EPSCs were recorded at −70 mV in the presence of 10 µM bicuculline, a GABAA receptor blocker. When the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) was examined, paired-pulses with 70 ms interval were given every 20 s. The PPR was the ratio of averaged amplitude of the second eIPSCs (eIPSC2s) to that of the first eIPSCs (eIPSC1s).

Figure 1.

Capsaicin depressed evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (eIPSCs) and increased the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) of eIPSCs through TRPV1 channels in ventrolateral periaqueductal gray (vlPAG) slices. IPSCs evoked at 0.05 Hz were recorded at 0 mV in the presence of 2 mM kynurenic acid, an ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonist. A. The time course of the effect of capsaicin (3 µM) on eIPSC amplitude and its reversal by 20 µM SB 366791. The representative eIPSC trace shown is the average of 12 eIPSCs taken before (a) or after treatment with capsaicin (b) or with capsaicin + SB 366791 (c). B. The time course of 3 µM capsaicin effect on eIPSC amplitude in a slice pretreated with 20 µM SB 366791. The upper panel shows a representative eIPSC recorded before (a) or after treatment with SB 366791 (b) or with SB 366791 + capsaicin (c). C. Averaged eIPSC amplitude, expressed as % of control, in the presence of 1, 3 and 10 µM capsaicin. D. Averaged eIPSC amplitude in the presence of 3 µM capsaicin (Cap) with 20 µM SB 366791 post-treated (Cap + SB) or pretreated (SB + Cap) and SB 366791 alone (SB). The numbers in the parentheses are the numbers of recorded neurons. E. Representative paired eIPSCs evoked by 70 ms-separated paired-pulses before (Control) and after (Capsaicin) treatment with 3 µM capsaicin. F. The paired pulse ratio (PPR) in control (Con) and capsaicin-treated (Cap) slices. PPR was the ratio of the averaged amplitude of eIPSC2s to the averaged amplitude of eIPSC1s. G. A diagram illustrating the positions of the stimulating (a) and recording (b) electrodes, respectively, in the vlPAG of a slice. A single bar represents an individual group with the treatment indicated (Student's t-test). Grouped bars represent different treatments within the same group (paired t-test). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. control, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. capsaicin. The same statistical analysis was applied to Figures 1–6.

Evoked PSPs were recorded in the current clamp mode in the absence of receptor blockers in the aCSF solution or a Na+ channel blocker (QX314) in the internal solution. With these conditions, either depolarized or hyperpolarized PSPs could be evoked, depending on the weighting of the stimulated excitatory or inhibitory input, and action potentials could be triggered if the depolarized ePSPs reached threshold (Chiou and Huang, 1999).

mIPSCs and mEPSCs

Miniature IPSCs were recorded at 0 mV in the presence of 2 mM kynurenic acid and 1 µM tetrodotoxin (TTX), a Na+ channel blocker that blocks the action potential-driven spontaneous IPSCs. Miniature EPSCs were recorded at −70 mV in the presence of TTX and 10 µM bicuculline.

Data acquisition and analysis

Signals were acquired at 5–10 kHz with an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA), and digitized at 10 kHz using an AD-converter (Digidata 1322A, Axon Instruments). Clampfit 8.2 (Axon Instruments) was used for off-line data analysis of eIPSCs, eEPSCs and ePSPs. After reaching the whole-cell configuration, the eIPSCs/eEPSCs were monitored for at least 15 min until they reached a steady state. Then, the tested drug was applied. The amplitudes of 12 eIPSCs or eEPSCs were averaged before and after drug treatment, ensuring that steady state had been reached; typically 6–12 min. Miniature EPSCs and IPSCs were recorded for 5 min before and at steady state after drug treatment. Mini Analysis 6.0 (Synaptosoft Inc, Leonia, NJ, USA) was used to analyse the frequency and amplitude of mIPSCs and mEPSCs.

Behavioural study

Intra-PAG injection

Male Wistar rats (6–8 weeks of age) were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (i.p. 40 mg·kg−1) and implanted with a 15 mm-long guide cannula 1 mm above the right vlPAG (AP: −7.8 mm from bregma, LM: −0.5 mm from midline, DV: −4.5 mm), according to the stereotaxic coordinates of the rat. After cannulation, rats were returned to their home cages in an animal room with 12 h light–dark cycle and food and water accessible ad libitum. The recovery time from the surgery was at least 7 days. On the day of nociceptive behavioural experiments, a 30 gauge injection cannula, connected to a 1 µL Hamilton syringe with 60 cm of PE-20 tube, was extended 1 mm beyond the tip of guide cannula for injecting the tested drug solution into the vlPAG area. A microinfusion pump (KDS311, KD Scientific Inc., Holliston, MA, USA) was used to deliver the drug solution of 0.2 µL over 2 min. When receptor antagonists were co-injected with capsaicin, twofold-concentrated drug solutions were injected to keep the injection volume at 0.2 µL. Antagonist solution, 0.1 µL, was injected followed by 0.1 µL of capsaicin solution. The injection cannula was left at the injection site for an additional 4 min to allow complete diffusion of the tested drug. To confirm the site of microinjection, 0.4% Trypan blue solution was injected through the cannula, and the rat was killed after the hot-plate test. The midbrain block was dissected, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and cut into 30 µm-thick slices by a cryostat microtome (Leica CM3050 S, Leica Microsystems, Nussloch, Germany). Data from rats with an injection site outside of the vlPAG were discarded; fewer than 7% of the rats were in this category.

Hot-plate test

The paw withdrawal latency to thermal stimulation on a hot plate of 50°C was recorded before and 5 min after intra-vlPAG drug administration, and was then further monitored every 10 min for 60 min. The withdrawal cut-off time was 60 s. The anti-nociceptive effect of the test drug was expressed as percentage of maximal possible effect (%MPE): %MPE = 100 × (withdrawal latencyafter treatment− withdrawal latencybefore treatment)/60 s − withdrawal latencybefore treatment).

Data analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and n indicates the number of the neurons recorded (in vitro) or the animals tested (in vivo). In the in vitro study, one neuron was recorded from one slice, and three to four slices were dissected from each rat. Student's t-test was used for statistical comparisons between groups, and paired t-test for those within group. Komogorov-Smirnov test was used to compare the distribution of the frequency and amplitude of mIPSCs and mEPSCs between control and capsaicin-treated conditions. In the in vivo study, two-way repeated measures analysis of variance with post hoc Bonferroni test was used for statistical comparisons between groups. Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Materials

Capsaicin, kynurenic acid, 1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-4-methyl-N-1-piperidinyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide (AM251) and (-)-tetrahydrolipstatin (THL) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). 4′-Chloro-3-methoxycinnamanilide (SB 366791), 7-(hydroxyimino)cyclopropa[b]chromen-1a-carboxylate ethyl ester (CPCCOEt), 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine hydrochloride (MPEP) (-)-bicuculline methiodide and TTX were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). Hydrophobic drugs were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), and hydrophilic drugs were dissolved in deionized water as 1000-fold concentrated stock solutions (in vitro) or in 0.9% normal saline as the concentrations needed (in vivo). Kynurenic acid was dissolved in aCSF directly before use. The final concentration of DMSO was less than 0.1%, which had no effect per se.

Results

Capsaicin depressed GABAergic eIPSCs through activation of TRPV1 channels

IPSCs can be easily evoked in a vlPAG slice in the presence of kynurenic acid, a blocker of ionotropic glutamate receptors, by placing the stimulation electrode 50–250 µm away from the recording electrode (Figure 1G). These eIPSCs are GABAergic since they were blocked by bicuculline, a GABAA receptor blocker (Chiou and Chou, 2000). Capsaicin, at 1–10 µM, decreased the amplitude of eIPSCs (Figure 1). The depressant effect of capsaicin was concentration-dependent and saturated at 3–10 µM (P < 0.05, n = 7, one-way anova analysis, Figure 1C). Therefore, 3 µM capsaicin was used in all the following experiments. This eIPSC depressant effect of capsaicin reached a steady state at 6–12 min, and was minimally reversed, even after 40 min washout (data not shown). Although capsaicin is well-known as a TRPV1 agonist, it may exert off-target effects, especially at higher concentrations (Kauer and Gibson, 2009). Therefore, we used a selective TRPV1 channel antagonist, SB 366791 (Gunthorpe et al., 2004), to confirm the involvement of TRPV1 channels. SB 366791 (20 µM) significantly reversed (n = 4, Figure 1A,D) and completely prevented (n = 5, Figure 1B,D) the eIPSC depressant effect of capsaicin (3 µM). SB 366791, at 20 µM, did not significantly affect eIPSCs amplitude per se (n = 4, Figure 1D).

Capsaicin depressed eIPSCs through a presynaptic mechanism

To decide if pre- or post-synaptic mechanism(s) contribute to capsaicin-induced eIPSC depression, we examined the effect of capsaicin on the PPR of paired eIPSCs evoked by 70 ms-separated pulses. An altered PPR is believed to be of presynaptic origin (Zucker and Regehr, 2002). Capsaicin (3 µM) decreased the amplitude of eIPSC1 in a pair of eIPSCs, and significantly increased the PPR (n = 5, Figure 1E,F). This suggests that capsaicin inhibits GABAergic transmission via a presynaptic mechanism; that is, decreasing evoked GABA release.

Capsaicin increased both mIPSC and mEPSC frequency

We further investigated if capsaicin affected postsynaptic receptor responses by examining its effect on mIPSCs. Capsaicin, at 3 µM, did not affect mIPSC amplitude (Figure 2A,D), but significantly increased the frequency of mIPSCs in each of six recorded neurons (Figure 2A–C). In addition, capsaicin (3 µM) also markedly increased the frequency of mEPSCs in each of five recorded neurons (Figure 3A–C) without affecting their amplitude (Figure 3A,D). The frequencies of both mIPSCs (Figure 2B) and mEPSCs (Figure 3B) were maintained at a higher level during a 10 min treatment with capsaicin, suggesting that no desensitization of TRPV1 channels occurred during capsaicin treatment.

Figure 2.

Capsaicin increased the frequency, but not amplitude, of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs). mIPSCs were recorded at 0 mV in the presence of 2 mM kynurenic acid and 1 µM tetrodotoxin (TTX). Shown are the representative traces (A), time course of the effect of capsaicin on mIPSC frequency (B), cumulative probability of inter-mIPSC interval (C) and that of mIPSC amplitude (D) during 5 min of control and capsaicin treatment, and the mean values of the frequency (C, inset) and amplitude (D, inset) of mIPSCs before and after treatment with 3 µM capsaicin. The Komogorov-Smirnov test shows a significant difference (P < 0.001) in the cumulative probability of inter-mIPSC interval (C), but not that of amplitude (D) of mIPSCs between capsaicin-treated and control groups.

Figure 3.

Capsaicin markedly increased the frequency of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs), but did not affect their amplitude. mEPSCs were recorded at −70 mV in the presence of 10 µM bicuculline and 1 µM TTX. Shown are the representative traces (A), time course of the effect of capsaicin on mEPSC frequency (B), cumulative probability of inter-mEPSC interval (C) and that of mEPSC amplitude (D) during 5 min of control and capsaicin treatment, and the mean values of the frequency (C, inset) and amplitude (D, inset) of mEPSCs before and after treatment with 3 µM capsaicin. The Komogorov-Smirnov test shows a significant difference (P < 0.001) in the cumulative probability of inter-mEPSC intervals (C), but not that of amplitudes (D) of mEPSCs between capsaicin-treated and control groups.

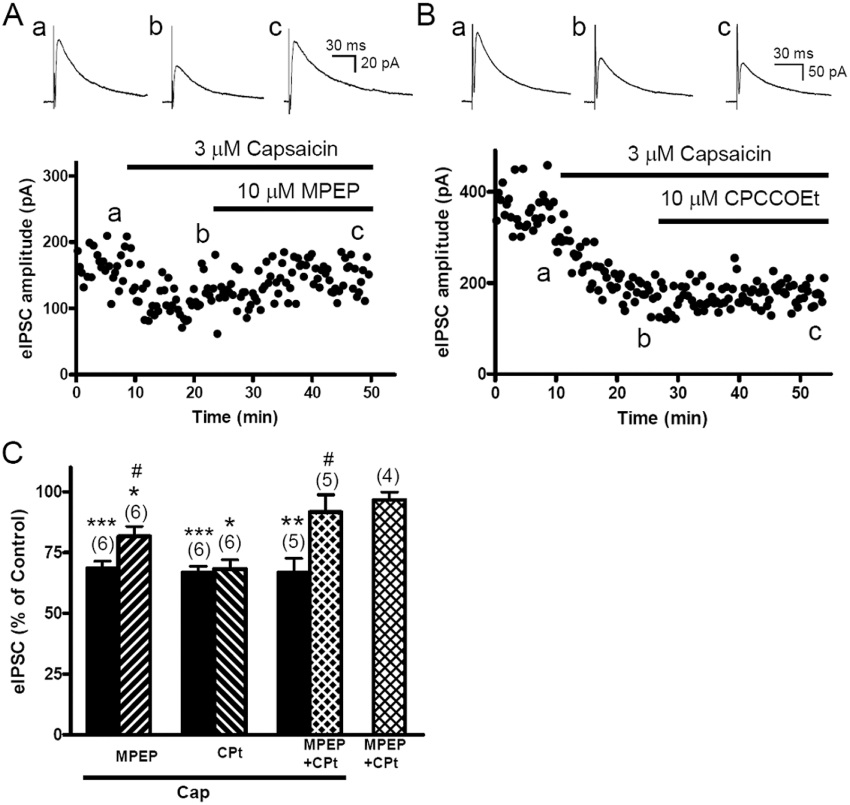

Capsaicin-induced eIPSC depression was reversed by a mGlu5 but not by a mGlu1 receptor antagonist

The anti-nociceptive effect induced by intra-PAG injection of capsaicin was completely blocked by group I mGlu receptor antagonists (Palazzo et al., 2002). Since group I mGlu receptors are located mainly perisynaptically (Nusser et al., 1994), to activate them, a large amount of glutamate is expected to diffuse from the synapse. The finding that capsaicin markedly increased mEPSC frequency (Figure 3) suggests that capsaicin may release large amounts of glutamate to activate perisynaptic group I mGlu receptors, followed by inhibition of eIPSCs in the vlPAG, leading to anti-nociception. Therefore, we examined if group I mGlu receptors were involved in capsaicin-induced eIPSC depression. MPEP (10 µM), an mGlu5 receptor antagonist, significantly reversed capsaicin (3 µM)-depressed eIPSCs (Figure 4A), to levels slightly, but significantly, smaller than the control levels (n = 6, P < 0.05; Figure 4C). Conversely, CPCCOEt (10 µM), an mGlu1 receptor antagonist, did not significantly affect the eIPSC depressant effect of capsaicin (n = 6, Figure 4B,C). Both antagonists had no effect on eIPSCs per se (n = 4, Figure 4C). When MPEP and CPCCOEt were co-applied, the eIPSCs were reversed to control levels (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Capsaicin depressed evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (eIPSCs), effects reversed by the mGlu5 (MPEP), but not mGlu1 (CPCCOEt), receptor antagonist. A. The time course of the effect of capsaicin on eIPSC amplitude in a slice treated with capsaicin (3 µM) followed by MPEP (10 µM). The representative eIPSC trace shown is the average of 12 eIPSCs taken before (a) or after treatment with capsaicin (b), or with capsaicin + MPEP (c). B. The time course of the effect of capsaicin on eIPSC amplitude in the slice treated with capsaicin (3 µM) followed by CPCCOEt (10 µM). The representative eIPSC trace shown is the average of 12 eIPSCs taken before (a) or after treatment with capsaicin (b), or with capsaicin + CPCCOEt (c). C. The mean values of eIPSC amplitude, expressed as % of control, in the slices treated with capsaicin (Cap) alone, followed by a combination of capsaicin with MPEP, CPCCOEt (CPt) and MPEP + CPCCOEt. Effects of MPEP + CPCCOEt given alone is also shown.

Capsaicin-induced eIPSC depression was blocked by AM251, a CB1 receptor antagonist and prevented by THL, a DAGL inhibitor

Activation of mGlu5 receptors resulted in biosynthesis of 2-AG, but not anandamide, via Gq-protein-coupled PLC activation and subsequent DAG hydrolysis by DAGL in several brain regions (Kano et al., 2009), including the PAG (Drew et al., 2009). This 2-AG subsequently produced retrograde inhibition of neurotransmitter release via presynaptic CB1 receptors (Drew et al., 2008, 2009; Mitchell et al., 2009). Therefore, we examined if this mGlu5 receptor-mediated PLC-DAGL-2AG retrograde inhibition pathway was involved in capsaicin-induced eIPSC depression.

First, we examined if AM251, a selective CB1 receptor antagonist, reversed the effect of capsaicin. AM251, at 3 µM, had no effect on eIPSC amplitude per se (n = 4, P > 0.05; Figure 5B), but reversed the mean amplitude of eIPSCs depressed by capsaicin (3 µM) to control values (Figures 5, n = 6, P > 0.05). At the same concentration, AM251 completely reversed the eIPSC depressant effect induced by WIN55,212-2, a CB1 receptor agonist (Figure S1). Furthermore, the capsaicin-induced PPR elevation was not observed when AM251 (3 µM) was given as a pretreatment (n = 5, Figure 5C), suggesting that capsaicin indirectly inhibited GABA release, through CB1 receptors, by affecting the presynaptic release machinery.

Figure 5.

Capsaicin-induced evoked inhibitory postsynaptic current (eIPSC) depression was reversed by AM251, a CB1 receptor antagonist, and prevented by a DAGL inhibitor (-)-tetrahydrolipstatin (THL). A. The time course of the effect of capsaicin on eIPSC amplitude in a slice treated with capsaicin (3 µM) followed by AM251 (3 µM). The representative eIPSC trace shown is the average of 12 eIPSCs taken before (a) or after treatment with capsaicin (b) or with capsaicin + AM251 (c). B. The mean values of eIPSC amplitude in the presence of capsaicin (Cap), capsaicin + AM251 and AM251 alone. C. The paired pulse ratio (PPR) in control (Con) and capsaicin + AM251-treated (Cap + AM251) slices. PPR was the ratio of the averaged amplitude of eIPSC2s to the averaged amplitude of eIPSC1s. D. The time course of the effect of capsaicin on eIPSC amplitude in a slice pretreated with 10 µM THL followed by capsaicin (3 µM). The representative eIPSC trace shown is the average of 12 eIPSCs taken before (a) or after treatment with THL (b), or with capsaicin + THL (c). E. The mean values of eIPSC amplitude in the presence of capsaicin, THL + capsaicin and THL alone.

Second, we confirmed that 2-AG is the endocannabinoid that was synthesized after mGlu5 receptor activation by testing the effects of THL, a DAGL inhibitor, on the responses to capsaicin. In contrast to depressing eIPSCs, capsaicin (3 µM) did not affect eIPSCs in slices pretreated with 10 µM THL (Figure 5D,E). THL (10 µM) had no effect on eIPSCs per se (n = 5, Figure 5E).

Capsaicin also depressed glutamatergic eEPSCs via CB1 receptors

We further examined if the endocannabinoid generated after capsaicin treatment might also depress glutamatergic eEPCSs in vlPAG slices. Indeed, the amplitude of eEPSCs was significantly decreased by capsaicin (3 µM) and reversed by 3 µM AM251 (n = 5, Figure 6). AM251 (3 µM) had no effect on eEPSC amplitude per se (n = 4, P > 0.05; Figure 6B). Nevertheless, the eEPSCs, compared with eIPSCs, were significantly less depressed by capsaicin (3 µM) (n = 5, 77.9% ± 2.0% vs. n = 6, 67.1% ± 3.2% of the controls, P < 0.05) (Figure 6B vs. Figure 5B).

Figure 6.

Capsaicin decreased evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (eEPSCs) in vlPAG neurons, effects reversed by AM251. EPSCs evoked at 0.05 Hz were recorded at −70 mV in the presence of 10 µM bicuculline, a GABAA receptor blocker. A. The time course of the effect of capsaicin on eEPSC amplitude in a slice treated with capsaicin (3 µM) followed by AM251 (3 µM). The representative eEPSC trace shown is the average of 12 eIPSCs taken before (a) or after treatment with capsaicin (b) or with capsaicin + AM251 (c). B. The mean values of eEPSC amplitude in the presence of capsaicin (Cap), capsaicin + AM251 and AM251 alone.

Capsaicin exhibited an overall excitatory effect on the vlPAG neuronal activity

Anatomically, both glutamatergic (Beitz and Williams, 1990) and GABAergic terminals (Reichling and Basbaum, 1990) form axodendritic synapses on PAG neurons. Electrophysiological recordings also demonstrated that glutamatergic eEPSCs/eEPSPs and GABAergic eIPSCs/eIPSPs can be recorded in the same vlPAG neuron (Chieng and Christie, 1994; Chiou and Chou, 2000). These suggest that vlPAG neurons receive both glutamtergic and GABAergic inputs.

Given that capsaicin depressed both eIPSCs and eEPSCs, we further examined the overall effect of capsaicin on the neuronal activity of vlPAG slices under the current clamp recording mode. Local stimulation in rat vlPAG slices can induce either hyperpolarized or depolarized ePSPs, depending on the weighting of the excitatory (glutamatergic) or inhibitory (GABAergic) input on the recorded neuron (Chiou and Huang, 1999). Among nine recorded neurons, depolarized ePSPs were recorded in eight neurons and hyperpolarized PSPs were obtained in one neuron. Capsaicin caused membrane depolarization in 7/9 of the recorded neurons (from −64.7 ± 2.0 to −60.3 ± 2.2 mV; n = 7, P < 0.05, paired t-test). In four neurons, capsaicin increased the amplitude of depolarized ePSPs (Figure 7A) from 4.3 to 4.7, 5.2 to 5.6, 3.0 to 3.5, and 2.4 to 3.6 mV, respectively, giving the mean change from 3.7 ± 0.6 to 4.3 ± 0.5 mV (n = 4, P < 0.05, paired t-test). In two of these four neurons, membrane potentials were depolarized. After correcting membrane potentials back to the control values, the increment of ePSPs was further enhanced (right column in Figure 7A). In another four neurons, capsaicin apparently decreased depolarized ePSPs (Figure 7B). However, in two neurons with membrane potentials depolarized by capsaicin, correcting the membrane potentials converted the changes in ePSP amplitude from depression to enhancement; the ePSP amplitudes were changed in these two neurons from 2.2 to 1.9, and then to 3.0 mV and from 5.4 to 4.6, and then to 5.6 mV respectively. In four neurons, the ePSPs were so enhanced that triggered action potentials after capsaicin treatment (Figure 7C,D). In the neuron with hyperpolarized ePSPs, capsaicin decreased the amplitude of these hyperpolarized ePSPs, even after membrane potential correction (Figure 7E). Note that capsaicin increased the frequency of spontaneous excitatory PSPs (glutamatergic) (arrows in Figure 7) in all the recorded neurons even at the neuron receiving stronger GABAergic input (with hyperpolarized ePSPs) (Figure 7E). Overall, in most of the neurons treated with capsaicin, more depolarized ePSPs were recorded, which ultimately reached threshold and triggered action potentials in some neurons.

Figure 7.

Capsaicin exerted excitatory effects on neuronal activity in vlPAG slices. Postsynaptic potentials (PSPs) evoked at 0.05 Hz by presynaptic stimulation were recorded in the current clamp mode without any receptor antagonists in aCSF. Either depolarized PSPs (A–C) or hyperpolarized PSP (E) could be evoked in control slices. Capsaicin (3 µM) induced membrane depolarization in some neurons (A,B,E). It increased depolarized ePSPs (A,B) after correcting the membrane potential (MP) (right column), whether the ePSPs were initially increased (A) or decreased (B). In some neurons, the increment of depolarized ePSPs was large enough to elicit action potentials (C,D). D. Overlapping traces of the ePSPs before and after treatment with capsaicin, which were taken from the neuron in C, but with a lower magnification scale. Capsaicin decreased hyperpolarized ePSPs at both depolarized and corrected membrane potentials (E). Note that capsaicin increased spontaneous EPSPs (arrows) whether depolarized PSPs (A–C) or hyperpolarized PSPs (E) were evoked.

Intra-vlPAG microinjection of capsaicin induced anti-nociception via mGlu receptor-mediated 2-AG retrograde signalling

To verify if the actions of capsaicin observed in PAG slices can contribute to its anti-nociceptive action, we further performed an in vivo study using the hot-plate pain model in the rat. Microinjections of capsaicin (6 nmol) into the vlPAG increased the withdrawal latency in the rat hot-plate test (Figure 8). The anti-nociceptive effect of capsaicin was up to 50% MPE at 5 min after injection and then decreased within 10 min to around 20%, lasting for 40 min (n = 7, Figure 8A). Intra-vlPAG microinjection of SB 366791 (50 nmol) did not change the withdrawal latency per se but completely abolished the anti-nociceptive effect of capsaicin (n = 6, Figure 8A). MPEP (50 nmol), an mGlu5 receptor antagonist (n = 6, Figure 8B) and AM251 (30 nmol), a CB1 receptor antagonist (n = 6, Figure 8C) significantly attenuated, though not completely abolished, the anti-nociceptive effect of capsaicin. Both antagonists and vehicle did not change the withdrawal latency per se (n = 6, Figure 8A–C).

Figure 8.

Intra-vlPAG microinjection of capsaicin induced anti-nociception via TRPV1 channels and mGlu5 receptor-mediated retrograde inhibition by 2-AG in the rat hot-plate test. All drugs were given by intra-vlPAG microinjection. The withdrawal cut-off time was 60 sec. Data shown are the mean anti-nociceptive effect in each treatment group at the same time point. The anti-nociceptive effect was expressed as percentage of maximal possible effect (MPE): %MPE = 100 × (withdrawal latencyafter treatment− withdrawal latencybefore treatment)/60 s − withdrawal latencybefore treatment). (A) Time courses of the MPE in rats treated with vehicle, capsaicin (6 nmol), capsaicin + SB 366791 (50 nmol) and SB 366791 alone. (B) Time courses of the MPE in rats treated with vehicle, capsaicin (6 nmol), capsaicin + MPEP (50 nmol) and MPEP alone. (C) Time courses of the MPE in rats treated with vehicle, capsaicin (6 nmol), capsaicin + AM251 (30 nmol) and AM251 alone. The numbers in the parentheses are the numbers of rats used. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. control, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. capsaicin (two-way repeated measures anova with post hoc Bonferroni test).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that capsaicin facilitated glutamate release via activating TRPV1 channels on glutamatergic terminals, followed by activation of postsynaptic mGlu5 receptors to generate 2-AG through the Gq-protein-coupled PLCβ-DAGLα pathway. 2-AG then retrogradely inhibited GABA release via presynaptic CB1 receptors (Figure 9). This disinhibition mechanism in the vlPAG leads to activation of the descending pain inhibitory pathway and contributes to intra-vlPAG capsaicin-induced anti-nociception. This study not only revealed a novel TRPV1 channel-mediated anti-nociceptive mechanism in the vlPAG, but also disclosed a positive interaction with endocannabinoids downstream to vanilloids.

Figure 9.

A proposed model for capsaicin-induced depression of GABAergic transmission in the vlPAG ultimately leads to activation of the descending pain inhibitory pathway and anti-nociception. The diagram shows the GABAergic (right) and glutamatergic (left) synapses in a vlPAG neuron before (A) and after (B) capsaicin treatment. Capsaicin activates TRPV1 channels located on glutamatergic terminals to facilitate glutamate release, which subsequently activates postsynaptic mGlu5 receptors (mGluR5) and then, coupled by Gq protein, stimulates phospholipase C (PLC) to yield diacylglycerol (DAG) which is then de-acylated by DAG lipase (DAGL) to 2-arachidonolyglycerol (2-AG), an endocannabinoid. 2-AG acts as a retrograde messenger to activate presynaptic CB1 receptors (CB1) located on the GABAergic terminals to inhibit GABA release. Inhibition of the GABAergic transmission (disinhibition) in the vlPAG will activate the descending pain inhibitory pathway and reduce nociceptive responses.

Capsaicin inhibits GABAergic transmission indirectly by releasing glutamate via TRPV1 channels, followed by mGlu5 receptor-mediated 2-AG retrograde signalling in vlPAG slices

Capsaicin-induced eIPSC depression and PPR facilitation were both blocked by AM251, suggesting capsaicin inhibits GABA release through endocannabinoids acting on CB1 receptors, which are located presynaptically (Tsou et al., 1998). This effect was antagonized by SB 366791, a selective TRPV1 channel antagonist (Gunthorpe et al., 2004), suggesting it is TRPV1-mediated. Its resistance to washout may be due to the lipophilicity and intracellular binding of capsaicin (Jordt and Julius, 2002).

Endocannabinoid retrograde inhibition can be initiated by activation of several GqPCRs in the vlPAG, including mGlu5 receptors (Drew et al., 2008, 2009; Mitchell et al., 2009), M1/M3 muscarinic (Lau and Vaughan, 2008) and orexin 1 (Chiou and Ho, 2009) receptors. Among these, the mGlu5 receptors are the most likely GqPCRs activated after capsaicin treatment since MPEP (a mGlu5 receptor antagonist) markedly attenuated capsaicin-induced eIPSC depression. mGlu1 receptors might also have a small contribution since co-application of mGlu1 and mGlu5 receptor antagonists completely reversed the depression.

2-AG is believed to be the endocannabinoid generated after GqPCR activation (Kano et al., 2009). GqPCR activation leads to PLCβ activation and yields DAG, which is then de-acylated by DAGLα to 2-AG. Our finding that a DAGL inhibitor, THL, prevented capsaicin-depressed eIPSCs suggests that 2-AG, but not anandamide, is the endocannabinoid involved the effect of capsaicin.

In addition to the GqPCR-PLCβ-DAGLα pathway, endocannabinoids could be synthesized by elevated intracellular Ca2+, which entered through postsynaptic TRPV1 channels (Di Marzo et al., 2001; Ahluwalia et al., 2003). This, however, can be ruled out since a combination of group I mGlu receptor antagonists completely reversed capsaicin-depressed eIPSCs. Endocannabinoids could also be generated by membrane depolarization (Ohno-Shosaku et al., 2001; Wilson and Nicoll, 2001). Since AM251 alone did not affect eIPSCs, it is unlikely that endocannabinoids were generated by the depolarized potential held for recording eIPSCs and thus contributed to eIPSC inhibition.

The finding that capsaicin dramatically increased mEPSC frequency suggests that capsaicin activates presynaptic TRPV1 channels to release a large amount of glutamate, which then activates mGlu5 receptors, which are located mainly in the perisynaptic region (Nusser et al., 1994), and subsequent 2-AG retrograde inhibition of eIPSCs in vlPAG slices (Figure 9).

This capsaicin-activated mGlu5 receptor-endocannabinoid retrograde signalling is comparable to mGlu5 receptor activation indirectly via neurotensin (Mitchell et al., 2009) or neurokinin (Drew et al., 2009) receptors or directly via glutamate spillover induced by blocking glutamate transporters (Drew et al., 2008) in vlPAG slices. Interestingly, endocannabinoids inhibited eIPSCs by ∼30% in all the experiments mentioned above. We demonstrated here this 30% depression of GABAergic transmission is sufficient to produce anti-nociception (Figure 8), by exciting the vlPAG (Figure 7).

Gibson et al. (2008) found another interesting retrograde signalling mediated by a lipid endovanilloid, 12-(S)-HPETE, after activation of postsynaptic mGlu5 and mGlu1 receptors in the hippocampus. In our study, mGlu receptor and CB1 receptor antagonists markedly and comparatively reversed capsaicin-depressed eIPSCs. Therefore, it is unlikely that this depression is mediated by an mGlu receptor-dependent and CB1 receptor-independent endovanilloid retrograde signalling. Nevertheless, our data cannot exclude the possibility that 12-(S)-HPETE might act as a positive feedback endovanilloid to further activate the TRPV1 channel-mediated mGlu receptor-2-AG retrograde disinhibition in the vlPAG, although anandamide has been proposed to be an endovanilloid in the vlPAG (Maione et al., 2006). Several endovanilloids have been identified (Flores and Vasko, 2010). It remains to be further elucidated which endovanilloid(s) can be generated under noxious stimulation to produce an anti-nociceptive protective tone through this TRPV1 channel-mGlu receptor-2-AG retrograde signalling in the vlPAG.

Capsaicin excites the vlPAG mainly via 2-AG retrograde disinhibition but not postsynaptic depolarization

The finding that capsaicin induced more depolarized ePSPs suggests that it produced an overall excitatory effect on vlPAG neurons after summating its effects on excitatory and inhibitory transmissions. Indeed, capsaicin depressed eIPSCs to a greater extent than eEPSCs, while AM251 reversed both effects of capsaicin. This suggests that 2-AG retrograde disinhibition, induced indirectly through presynaptic TRPV1 channel activation, plays a dominant role in capsaicin-induced ePSP facilitation and subsequent neuronal excitation. This preferential inhibitory effect of endocannabinoids on GABA, rather than glutamate, transmission could be due to: (i) a greater density of CB1 receptors on inhibitory terminals (i-CB1 receptors) than on excitatory terminals (e-CB1 receptors) (Kano et al., 2009); (ii) degradation and uptake of endocannabinoids selectively prevent them from reaching excitatory terminals (Hentges et al., 2005); and (iii) e-CB1 receptors are less sensitive to cannabinoids than i-CB1 receptors (Ohno-Shosaku et al., 2002).

Capsaicin induced postsynaptic membrane depolarization in 2/3 of the recorded neurons, which could be attributed to activation of postsynaptic TRPV1 channels Immunocytochemical studies have shown that, in addition to presynaptic terminals, TRPV1 channels are also located postsynaptically in vlPAG neurons (Cristino et al., 2006; Maione et al., 2006). This postsynaptic depolarizing effect of capsaicin, while it might directly enhance neuronal activity, did not contribute to capsaicin-enhanced ePSPs since ePSPs were increased, rather than decreased, after correcting membrane depolarization (Figure 7A,B).

Anti-nociception results from excitation of the vlPAG

Anti-nociception can be induced via inhibiting intrinsic GABAergic tone (disinhibition) in the vlPAG (Behbehani et al., 1990) to activate the descending pain inhibitory pathway. Our in vivo study demonstrated that intra-vlPAG injection of capsaicin produced anti-nociception, which corresponds to the increased neuronal activity observed in vlPAG slices after capsaicin treatment. The anti-nociceptive effect of capsaicin was completely abolished by a TRPV1 channel antagonist, and was markedly attenuated by mGlu5 receptor and CB1 receptor antagonists (Figure 8). This suggests that the mGlu5 receptor-2-AG retrograde disinhibition, induced by activation of presynaptic TRPV1 channels, plays an important role in capsaicin-induced anti-nociception in the vlPAG. Palazzo et al. (2002) also reported an mGlu5 receptor antagonist blocked capsaicin-induced anti-nociception in the dlPAG. The residual anti-nociceptive effect after blocking mGlu5 receptors or CB1 receptors may be the result of a TRPV1 channel-mediated and endocannabinoid-independent effect, such as a direct postsynaptic depolarization of the PAG projection neurons (Starowicz et al., 2007).

Activation of TRPV1 channels in the vlPAG leads to opposing effects on spontaneous and evoked transmitter release

In this study, capsaicin decreased evoked transmitter release (eEPSCs/eIPSCs) indirectly through presynaptic CB1 receptors, but increased spontaneous release (mEPSC/mIPSC frequency) directly via presynaptic TRPV1 channels. This could occur concurrently at the presynaptic site of a recorded neuron (Figure 7E). However, the overall neuronal excitability is decided by a summation of evoked release, but not by spontaneous release, of excitatory (glutamate) and inhibitory (GABA) neurotransmitters. Capsaicin inhibited evoked release, although it increased spontaneous release. Its greater inhibition of evoked GABA release than of evoked glutamate release ultimately leads to PAG excitation. Similar opposing effects of capsaicin on evoked and spontaneous releases were also reported (Marinelli et al., 2002; Marinelli et al., 2003; Derbenev et al., 2006).

Capsaicin-inhibited evoked neurotransmitter release has been attributed to depolarization block (Katz and Miledi, 1969; Yang et al., 1999; Baccei et al., 2003; Marinelli et al., 2003), calcium channel internalization (Docherty et al., 1991; Wu et al., 2005; Gibson et al., 2008) and/or neurotransmitter depletion (Derbenev et al., 2006). Here, we have demonstrated that mGlu5 receptor-2-AG retrograde inhibition is a novel, and the main, mechanism for inhibition by capsaicin.

Capsaicin increased mEPSC/mIPSC frequencies, but not their amplitudes, suggesting it facilitated action potential-independent spontaneous release of glutamate or GABA as reported previously (Li et al., 2004; Derbenev et al., 2006; Steenland et al., 2006; Xing and Li, 2007; Musella et al., 2009), and had no effect on postsynaptic glutamate or GABA receptors. This facilitatory effect was attributed to a TRPV1 channel-mediated presynaptic terminal depolarization. Marinelli et al. (2002) showed this effect of capsaicin at higher concentrations desensitized rapidly. However, our study showed capsaicin at 3 µM increased mEPSC/mIPSC frequencies without loss of effect at least for 10 min (Figures 2B,3B).

Interplay between TRPV1 channels and CB1 receptors

Interplay between TRPV1 channels and CB1 receptors have been actively studied. Some focused on the dualistic nature (activating both CB1 receptors and TRPV1 channels) of cannabinoids and vanilloids (Di Marzo et al., 2002), such as anandamide, the first identified endocannabinoid, which also acts as an endovanilloid (Zygmunt et al., 1999; Smart et al., 2000). Crosstalk between these two receptors was also addressed. Activating CB1 receptors can lead to either potentiation, inhibition or desensitization of TRPV1 channels in cells co-expressing CB1 receptors and TRPV1 channels (Hermann et al., 2003; Jeske et al., 2006; Evans et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008). Recently, Maccarrone et al. (2008) demonstrated that anandamide, via TRPV1 channels, can counteract 2-AG-induced retrograde disinhibition (via CB1 receptors) in the striatum. Here, we demonstrated that, in marked contrast, CB1 receptor-mediated retrograde inhibition was positively modulated by TRPV1 channel activation. These results highlight the diversity of endocannabinoid signalling (Di Marzo and Cristino, 2008).

The sequential activation of TRPV1 channels followed by CB1 receptors observed in this study not only contributes to capsaicin-induced anti-nociception in the vlPAG, but also might explain the finding that peripheral TRPV1 channel-mediated nociception is CB1 receptor-dependent (Fioravanti et al., 2008). It remains to be elucidated if this sequential interaction might also contribute to the hypokinesia (Lee et al., 2006) and anti-emetic (Sharkey et al., 2007) actions induced by agonists affecting both cannabinoid and vanilloid receptors.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the grants from National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC98-2320-B002-011-MY3 and NSC98-2323-B002-012), National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan (NHRI-EX99-9506NI), National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan (Excellent Research Grant 98R0066-51), National Bureau of Controlled Drugs, Department of Health, Taiwan (DOH-NNB-98-1055), and China Medical University (99F008-307).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 12-(S)-HPETE

12-(S) hydroperoxy-eicosatetraenoic acid

- 2-AG

2-arachidonoylglycerol

- AM251

1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-5-(4-iodophenyl) -4-methyl-N-1-piperidinyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide

- CB

receptor, cannabinoid receptor

- CPCCOEt

7-(hydroxyimino)cyclopropa[b]chromen-1a -carboxylate ethyl ester

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DAGL

diacylglycerol lipase

- eEPSC

evoked excitatory postsynaptic current

- eIPSC

evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents

- ePSP

evoked postsynaptic potential

- GqPCR

Gq-protein coupled receptor

- mEPSC

miniature EPSC

- mGlu

receptor, metabotropic glutamate receptor

- mIPSC

miniature IPSC

- MPE

maximal possible effect

- MPEP

2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine hydrochloride

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PPR

paired-pulse ratio

- RVM

rostroventral medulla

- SB

366791, 4′-chloro-3-methoxycinnamanilide

- THL

(-)-tetrahydrolipstatin

- TRPV1

transient receptor potential vanilloid 1

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- vlPAG

ventrolateral periaqueductal gray

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1 WIN 55212-2 depressed eIPSCs in a manner reversed by AM251. The time course of the effect of WIN 55212-2 (3 µM), a CB1 receptor agonist, on eIPSC amplitude in the slice treated with WIN 55212-2 (3 µM) followed by AM 251 (3 µM). The representative eIPSC trace shown is the average of 12 eIPSCs taken before (a) or after treatment with WIN 55212-2 (b), or with WIN 55212-2 + AM 251 (c).

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Ahluwalia J, Yaqoob M, Urban L, Bevan S, Nagy I. Activation of capsaicin-sensitive primary sensory neurones induces anandamide production and release. J Neurochem. 2003;84:585–591. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 4th edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(Suppl 1):S1–S254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccei ML, Bardoni R, Fitzgerald M. Development of nociceptive synaptic inputs to the neonatal rat dorsal horn: glutamate release by capsaicin and menthol. J Physiol. 2003;549:231–242. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behbehani MM, Jiang MR, Chandler SD, Ennis M. The effect of GABA and its antagonists on midbrain periaqueductal gray neurons in the rat. Pain. 1990;40:195–204. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90070-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitz AJ, Williams FG. Localizaiton of putative amino acid transmitters in the PAG and their relationship to the PAG-raphe magnus pathway. In: Depulis A, Bandler R, editors. The Midbrain Periaqueductal Gray Matter. New York: Plenum; 1990. pp. 305–327. [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chieng B, Christie MJ. Inhibition by opioids acting on µ-receptors of GABAergic and glutamatergic postsynaptic potentials in single rat periaqueductal gray neurons in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;113:303–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb16209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou LC, Chou HH. Characterization of synaptic transmission in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray of rat brain slices. Neuroscience. 2000;100:829–834. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00348-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou L-C, Ho Y-C. Orexin A inhibits GABAergic neurotransmission via retrograde endocannabinoid through OX1 receptor activation in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray – a novel anti-nociceptive mechanism of orexin A. 2009. In: Neuroscience 2009, Abs. No. 418.4. Chicago, IL, USA.

- Chiou LC, Huang LY. Mechanism underlying increased neuronal activity in the rat ventrolateral periaqueductal grey by a mu-opioid. J Physiol. 1999;518:551–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0551p.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristino L, de Petrocellis L, Pryce G, Baker D, Guglielmotti V, Di Marzo V. Immunohistochemical localization of cannabinoid type 1 and vanilloid transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 receptors in the mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2006;139:1405–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbenev AV, Monroe MJ, Glatzer NR, Smith BN. Vanilloid-mediated heterosynaptic facilitation of inhibitory synaptic input to neurons of the rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9666–9672. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1591-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Cristino L. Why endocannabinoids are not all alike. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:124–126. doi: 10.1038/nn0208-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Lastres-Becker I, Bisogno T, De Petrocellis L, Milone A, Davis JB, et al. Hypolocomotor effects in rats of capsaicin and two long chain capsaicin homologues. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;420:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Blumberg PM, Szallasi A. Endovanilloid signaling in pain. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:372–379. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty RJ, Robertson B, Bevan S. Capsaicin causes prolonged inhibition of voltage-activated calcium currents in adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons in culture. Neuroscience. 1991;40:513–521. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90137-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew GM, Mitchell VA, Vaughan CW. Glutamate spillover modulates GABAergic synaptic transmission in the rat midbrain periaqueductal grey via metabotropic glutamate receptors and endocannabinoid signaling. J Neurosci. 2008;28:808–815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4876-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew GM, Lau BK, Vaughan CW. Substance P drives endocannabinoid-mediated disinhibition in a midbrain descending analgesic pathway. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7220–7229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4362-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RM, Scott RH, Ross RA. Chronic exposure of sensory neurones to increased levels of nerve growth factor modulates CB1/TRPV1 receptor crosstalk. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:404–413. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioravanti B, De Felice M, Stucky CL, Medler KA, Luo MC, Gardell LR, et al. Constitutive activity at the cannabinoid CB1 receptor is required for behavioral response to noxious chemical stimulation of TRPV1: anti-nociceptive actions of CB1 inverse agonists. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11593–11602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3322-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores CM, Vasko MR. The deorphanization of TRPV1 and the emergence of octadecadienoids as a new class of lipid transmitters. Mol Interv. 2010;10:137–140. doi: 10.1124/mi.10.3.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson HE, Edwards JG, Page RS, Van Hook MJ, Kauer JA. TRPV1 channels mediate long-term depression at synapses on hippocampal interneurons. Neuron. 2008;57:746–759. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthorpe MJ, Rami HK, Jerman JC, Smart D, Gill CH, Soffin EM, et al. Identification and characterisation of SB-366791, a potent and selective vanilloid receptor (VR1/TRPV1) antagonist. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:133–149. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinricher MM, Tavares I, Leith JL, Lumb BM. Descending control of nociception: specificity, recruitment and plasticity. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentges ST, Low MJ, Williams JT. Differential regulation of synaptic inputs by constitutively released endocannabinoids and exogenous cannabinoids. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9746–9751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2769-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann H, De Petrocellis L, Bisogno T, Schiano Moriello A, Lutz B, Di Marzo V. Dual effect of cannabinoid CB1 receptor stimulation on a vanilloid VR1 receptor-mediated response. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:607–616. doi: 10.1007/s000180300052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SM, Bisogno T, Trevisani M, Al-Hayani A, De Petrocellis L, Fezza F, et al. An endogenous capsaicin-like substance with high potency at recombinant and native vanilloid VR1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8400–8405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122196999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SW, Cho H, Kwak J, Lee SY, Kang CJ, Jung J, et al. Direct activation of capsaicin receptors by products of lipoxygenases: endogenous capsaicin-like substances. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6155–6160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeske NA, Patwardhan AM, Gamper N, Price TJ, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM. Cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 regulates TRPV1 phosphorylation in sensory neurons. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32879–32890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603220200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordt SE, Julius D. Molecular basis for species-specific sensitivity to ‘hot’ chili peppers. Cell. 2002;108:421–430. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00637-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano M, Ohno-Shosaku T, Hashimotodani Y, Uchigashima M, Watanabe M. Endocannabinoid-mediated control of synaptic transmission. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:309–380. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Miledi R. Spontaneous and evoked activity of motor nerve endings in calcium Ringer. J Physiol. 1969;203:689–706. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer JA, Gibson HE. Hot flash: TRPV channels in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SR, Bok E, Chung YC, Chung ES, Jin BK. Interactions between CB(1) receptors and TRPV1 channels mediated by 12-HPETE are cytotoxic to mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:253–264. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau BK, Vaughan CW. Muscarinic modulation of synaptic transmission via endocannabinoid signalling in the rat midbrain periaqueductal gray. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1392–1398. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.045872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Di Marzo V, Brotchie JM. A role for vanilloid receptor 1 (TRPV1) and endocannabinnoid signalling in the regulation of spontaneous and L-DOPA induced locomotion in normal and reserpine-treated rats. Neuropharmacology. 2006;51:557–565. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DP, Chen SR, Pan HL. VR1 receptor activation induces glutamate release and postsynaptic firing in the paraventricular nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1807–1816. doi: 10.1152/jn.00171.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao YY, Trapella C, Chiou LC. 1-Benzyl-N-[3-[spiroisobenzofuran-1(3H),4′-piperidin-1-yl]propyl]pyrrolidine-2-ca rboxamide (Compound 24) antagonizes NOP receptor-mediated potassium channel activation in rat periaqueductal gray slices. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;606:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccarrone M, Rossi S, Bari M, De Chiara V, Fezza F, Musella A, et al. Anandamide inhibits metabolism and physiological actions of 2-arachidonoylglycerol in the striatum. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:152–159. doi: 10.1038/nn2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maione S, Bisogno T, de Novellis V, Palazzo E, Cristino L, Valenti M, et al. Elevation of endocannabinoid levels in the ventrolateral periaqueductal grey through inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase affects descending nociceptive pathways via both cannabinoid receptor type 1 and transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:969–982. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.093286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli S, Vaughan CW, Christie MJ, Connor M. Capsaicin activation of glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the rat locus coeruleus in vitro. J Physiol. 2002;543:531–540. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.022863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli S, Di Marzo V, Berretta N, Matias I, Maccarrone M, Bernardi G, et al. Presynaptic facilitation of glutamatergic synapses to dopaminergic neurons of the rat substantia nigra by endogenous stimulation of vanilloid receptors. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3136–3144. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03136.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey E, Toth ZE, Cortright DN, Arzubi MK, Krause JE, Elde R, et al. Distribution of mRNA for vanilloid receptor subtype 1 (VR1), and VR1-like immunoreactivity, in the central nervous system of the rat and human. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3655–3660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060496197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ. Descending control of pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;66:355–474. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell VA, Kawahara H, Vaughan CW. Neurotensin inhibition of GABAergic transmission via mGluR-induced endocannabinoid signalling in rat periaqueductal grey. J Physiol. 2009;587:2511–2520. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musella A, De Chiara V, Rossi S, Prosperetti C, Bernardi G, Maccarrone M, et al. TRPV1 channels facilitate glutamate transmission in the striatum. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;40:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Mulvihill E, Streit P, Somogyi P. Subsynaptic segregation of metabotropic and ionotropic glutamate receptors as revealed by immunogold localization. Neuroscience. 1994;61:421–427. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyilas R, Gregg LC, Mackie K, Watanabe M, Zimmer A, Hohmann AG, et al. Molecular architecture of endocannabinoid signaling at nociceptive synapses mediating analgesia. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:1964–1978. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06751.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno-Shosaku T, Maejima T, Kano M. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signals from depolarized postsynaptic neurons to presynaptic terminals. Neuron. 2001;29:729–738. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno-Shosaku T, Tsubokawa H, Mizushima I, Yoneda N, Zimmer A, Kano M. Presynaptic cannabinoid sensitivity is a major determinant of depolarization-induced retrograde suppression at hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3864–3872. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-10-03864.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo E, Marabese I, de Novellis V, Oliva P, Rossi F, Berrino L, et al. Metabotropic and NMDA glutamate receptors participate in the cannabinoid-induced anti-nociception. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:319–326. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo E, de Novellis V, Marabese I, Cuomo D, Rossi F, Berrino L, et al. Interaction between vanilloid and glutamate receptors in the central modulation of nociception. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;439:69–75. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichling DB, Basbaum AI. The contribution of brain stem GABAergic circuitry to descending anti-nociceptive controls. II. Electron microscopic immunocytochemical evidence of GABAergic control over the projection from the periaqueductal gray matter to the nucleus raphe magnus. J Comp Neurol. 1990;302:378–393. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds DV. Surgery in the rat during electrical analgesia induced by focal brain stimulation. Science. 1969;164:444–445. doi: 10.1126/science.164.3878.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JC, Davis JB, Benham CD. [3H]Resiniferatoxin autoradiography in the CNS of wild-type and TRPV1 null mice defines TRPV1 (VR-1) protein distribution. Brain Res. 2004;995:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey KA, Cristino L, Oland LD, Van Sickle MD, Starowicz K, Pittman QJ, et al. Arvanil, anandamide and N-arachidonoyl-dopamine (NADA) inhibit emesis through cannabinoid CB1 and vanilloid TRPV1 receptors in the ferret. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:2773–2782. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart D, Gunthorpe MJ, Jerman JC, Nasir S, Gray J, Muir AI, et al. The endogenous lipid anandamide is a full agonist at the human vanilloid receptor (hVR1) Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:227–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starowicz K, Maione S, Cristino L, Palazzo E, Marabese I, Rossi F, et al. Tonic endovanilloid facilitation of glutamate release in brainstem descending anti-nociceptive pathways. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13739–13749. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3258-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starowicz K, Cristino L, Di Marzo V. TRPV1 receptors in the central nervous system: potential for previously unforeseen therapeutic applications. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:42–54. doi: 10.2174/138161208783330790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenland HW, Ko SW, Wu LJ, Zhuo M. Hot receptors in the brain. Mol Pain. 2006;2:34–41. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-2-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone TW. Neuropharmacology of quinolinic and kynurenic acids. Pharmacol Rev. 1993;45:309–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou K, Brown S, Sanudo-Pena MC, Mackie K, Walker JM. Immunohistochemical distribution of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the rat central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1998;83:393–411. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00436-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Nicoll RA. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signalling at hippocampal synapses. Nature. 2001;410:588–592. doi: 10.1038/35069076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZZ, Chen SR, Pan HL. Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 activation down-regulates voltage-gated calcium channels through calcium-dependent calcineurin in sensory neurons. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18142–18151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing J, Li J. TRPV1 receptor mediates glutamatergic synaptic input to dorsolateral periaqueductal gray (dl-PAG) neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:503–511. doi: 10.1152/jn.01023.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K, Kumamoto E, Furue H, Li YQ, Yoshimura M. Action of capsaicin on dorsal root-evoked synaptic transmission to substantia gelatinosa neurons in adult rat spinal cord slices. Brain Res. 1999;830:268–273. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt PM, Petersson J, Andersson DA, Chuang H, Sorgard M, Di Marzo V, et al. Vanilloid receptors on sensory nerves mediate the vasodilator action of anandamide. Nature. 1999;400:452–457. doi: 10.1038/22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.