Abstract

Many Americans do not experience a good death. The inadequate treatment of pain at the end of life has been associated with a lack of supportive public policies more than a lack of evidence-based clinical practices or organizational efforts. Given a widespread lack of understanding about pain policies, we examine the critical role played by state medical boards in developing pain policies and then apply event history analysis to identify the variables most critical to the formation of these policies. We develop an integrated model and evaluate the adoption of eight different types of pain policies. The analytic models incorporate fifteen years of observational data and test the impact of contextual, political, extrinsic, and institutional variables. They reveal that the presence of legal counselors on state medical boards has consistently increased the likelihood that state boards adopt policies associated with progressive pain management. Further, policy has been negatively influenced by historical activity: boards that previously adopted one pain policy have been less likely to subsequently adopt additional pain policies. This work illuminates mechanisms behind state pain-policy adoption and provides valuable information for advocates who seek to improve pain-management policy and reduce the amount of pain at the end of life.

Introduction

Persons dying from prolonged illnesses can, and should, experience a “good death” (Byock 1997; Field and Cassel 1997). Most Americans think a good death consists of dying at home, surrounded by family, and free from pain and suffering (Singer, Martin, and Kelner 1999), and Americans’ preference to die in such a dignified manner is stable regardless of one’s age, gender, ethnicity, or religious background (Last Acts 1997; Singer, Martin, and Kelner 1999). Moreover, three of every four Americans do not fear death as much as they fear being in pain at the time of death (Yankelovich Partners 2000). Despite these clearly stated and seemingly universal preferences, too many of the 3 million Americans who die in health care settings each year suffer needlessly in pain at the end of life (EOL) (Field and Cassel 1997). Nearly eight out of every ten hospital deaths occurred without a palliative care consultation and formal pain management (Pan et al. 2001; Smits, Furletti, and Vladeck 2002), and more than eight out of every ten older long-term care facility residents experienced untreated or undertreated pain at the time of death (Teno et al. 2004). The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC 2006) estimated that more than 70 percent of all Medicare decedents, regardless of their age or where they died, received an inadequate amount of pain management.

The pervasive undertreatment of pain does not appear to correlate with any lack of knowledge about the importance of clinical pain management as a component of good EOL care. In the last decade, several medical and nursing organizations established clinical practice guidelines for providing pain management as a part of routine EOL care (American Academy of Pain Medicine [AAPM] and American Pain Society [APS] 1996; Oncology Nursing Society 2002; American Nurses Association 2003). The AAPM and the APS went so far as to declare that effective pain management was an ethical obligation for all health care providers. Health care organizations have also increased their efforts to support the provision of EOL pain management (Haugen 2000). For instance, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) defined the assessment and management of pain as a quality of care indicator across all JCAHO-accredited institutions (Gordon, Berry, and Dahl 2000; JCAHO 2002).

Kaufman, Shim, and Russ (2006) determined that the translation of these clinical guidelines and organizational commitments was impeded by several barriers. These barriers included negative attitudes and disinterest among providers and patients, a lack of financial incentives to provide EOL care, and a lack of public policies that support the provision of EOL care. In this study, we focus on state medical board policies pertaining to pain management at the EOL for two reasons. Pain management has emerged as a top priority for improving EOL care because it is so notably underapplied even though it is desired universally (Fish-man 2005; National Consensus Project 2004), and pain-management policies appeared to be the least considered yet readily modifiable among the known barriers to providing EOL care. Our goals are to establish the critical role played by state medical boards in developing state pain-management policies and to apply an event-history analysis to identify the variables most critical to the formation of these policies.

Public Policies Pertaining to Pain Management

The Controlled Substance Act (CSA) of 1971 is the most prominent federal policy enactment pertaining to the management of pain at the EOL (Gilson, Maurer, and Joranson 2005). The CSA created a national system for classifying prescription drugs and required all health care providers who prescribe medications to register with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. The CSA is particularly pertinent to pain management at the EOL, because the act specified that opioid analgesics were necessary for the relief of pain and their availability for medical purposes must be ensured by restraining federal interference with physicians’ prescribing practices. However, since the passage of the CSA, Congress has made few efforts to address EOL care and only has succeeded inserting a one-line provision—a dedication of the calendar decade beginning January 1, 2001, as the “Decade of Pain Control and Research”—into an unrelated bill that became Public Law 106–386 (Library of Congress 2006). Furthermore, the recent curtailment of the attorney general’s oversight of state-based assisted suicide policies in Oregon and the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold the Terri Schiavo right-to-life case in the state of Florida indicate that efforts to expand executive or judicial policy pertaining to EOL care were being held in check (Associated Press 2005; Findlaw 2005). The pervasive lack of federal policy appears consistent with the constitutionally based tradition of leaving public oversight for health policy matters to state and local officials (Buzzee 2001; Rich and White 1996), and this lack of federal EOL policies may likely continue as a function of the new federalism and devolution in American government (Weil, Wiener, and Holahan 1998).

Joranson and Maurer (2003) resolved that state policies are far more critical in shaping EOL care. They specifically proposed that the provision of proper pain management at the EOL was alternatively promoted or constrained by state statutes and regulations regarding the use of controlled substances. To this point, the Institute of Medicine (Field and Cassel 1997) reported that states’ drug-prescribing laws, regulations, and medical-board guidelines were outdated and scientifically flawed relative to current medical knowledge about pain management. For instance, some state laws continue to indicate that opioids are not a common part of medical practice, and they should only be used as a last resort and in very limited amounts (Pain and Policy Studies Group [PPSG] 2003a). Under such a policy constraint, the provision of opioids as a form of pain management is compromised and considered illegal in some states.

Imhof and Kaskie (2007) confirmed that state governments assume broad authority over matters concerning pain management at the EOL. All fifty state legislatures have adopted a version of the federal CSA to establish an intrastate legal structure to control drugs with abusive potential (Joranson and Gilson 2003). Several state legislatures also have adopted intractable pain treatment acts (IPTAs) intended to address physician fears of regulatory scrutiny, and thereby ensure that patients who suffer at the EOL would not be denied opioids for pain relief (Joranson 1995; PPSG 2000). Moreover, Imhof and Kaskie (2007) report that state courts are increasingly more involved in promoting pain-management policy by handing down rulings concerning the undertreatment of pain at the EOL. For example, a California court recently held a physician liable for the inadequate treatment of pain according to current medical standards and awarded $1.5 million to the family of an elderly man who suffered intolerable pain right before his death (Compassion in Dying Federation 2005), and a nursing home in North Carolina was held liable for providing inadequate pain control to its residents (McIntire 2003). State governors also have shown support for pain-policy initiatives. Twenty-two states have established task forces to study pain and other EOL issues (National Conference of State Legislatures 1999–2003), and the National Association of State Attorneys General recently passed a resolution calling for improved pain policies (Edmondson 2006). Notwithstanding this wide range of state activity, Imhof and Kaskie (2007) conclude that primary public responsibility for development and oversight of EOL pain policy was assumed by state medical boards.

The Role of State Medical Boards and Pain-Management Policies

Given the highly technical nature of medical practice, state executives and legislators often delegate public oversight for matters pertaining to the practice of medicine to medical boards (Galusha 1988; Gerber and Teske 2000). As such, state medical boards have emerged as independent policy-making authorities with extensive responsibility for the clinical practice of medicine including establishing licensing, education, and training requirements; setting disciplinary and corrective measures for providers and health care organizations; and structuring a state regulatory system that supports the provision of effective, high-quality medical care to the citizens within their states (Galusha 1988; Hill 1993). More pertinent here is the considerable amount of responsibility medical boards assume for policies associated with pain management at the EOL and the clinical practices necessary to achieve them. Hill (1993) was among the first to link state medical board pain-management policies to the quality of care received at the bedside at the EOL. Hierarchically, state medical boards establish medical practice parameters for the state (including for the provision of pain management) and can frame health care organizational policy, develop clinical protocols, and monitor medical practice. Medical board policies impact patient outcomes at the EOL in significant and practical ways.

The University of Wisconsin’s PPSG (2000, 2003a, 2006) has examined state pain policies for more than a decade and has identified eight benchmark policies that create a framework that allows the practice of pain management to be consistent with current research and patient preferences (see table 1). The first pain-management–enhancing policy requires that controlled substances are recognized as necessary for the public health and requires the state to support the prescribing of medications to control pain. The second policy establishes that pain management is part of general medical practice, and the third policy affirms that the use of opioids, in particular, is a legitimate form of medical practice. The fourth policy simply encourages the practice of pain management. The fifth policy addresses practitioners’ concerns about regulatory scrutiny. The sixth policy addresses practitioner fears about prescribing opioids for pain and specifically indicates that dosage levels are not sufficient in determining the legitimacy of any given opioid prescription. The seventh policy is intended to dispel myths surrounding the dependency that may accompany the chronic use of high-dose opioids. The eighth policy clarifies that prescriptions for pain management are separate from those for addiction treatment. The eighth type of policy allows for any additional language that does not fit into the other categories. For example, it covers policies that promote an interdisciplinary approach to treating pain by including practitioners who can address the physical, psychological, social, and vocational issues associated with pain (PPSG 2003a). While each of these policies appears critical in providing a framework for pain management, we resolved that four were more explicitly linked to the provision of pain management at the bedside at the EOL: (a) pain management is part of general medical practice, (b) opioids are a legitimate form of professional practice, (c) prescription amount alone does not determine legitimacy, and (d) reducing physician’s fears of regulatory scrutiny.

Table 1.

Pain-Management–Enhancing and –Impeding Policies

| Pain-Management – Enhancing Provisions |

|---|

| Controlled substances are necessary for public health. |

| Pain management is part of medical practice. |

| Opioids are part of professional practice. |

| Pain management is encouraged. |

| Fear of regulatory scrutiny is addressed. |

| Prescription amount alone does not determine legitimacy. |

| Physical dependence or analgesic tolerance are not confused with addiction. |

| Other provisions that may enhance pain management are included. |

| Pain-Management-Impeding Provisions |

| Opioids only can be used as a treatment of last resort. |

| Opioids fall outside the boundaries of legitimate medical practice. |

| Physician discretion in prescribing pain medications should be limited. |

| Practitioners are subject to undue prescription reporting requirements. |

| The prescription of all opioids is categorized as a form of addiction treatment. |

| The number of days in which an opioid prescription can be filled is limited. |

| Other provisions are included that limit pain management. |

| Ambiguously stated policies that effectively curtail prescribing practices are included. |

Alternatively, Hill (1993) suggests that other types of medical-board pain-management policies can exert a negative influence on the provision of pain management at the EOL. In particular, he argues that state medical boards have created negative policies because they misinterpreted guber-natorial directives or legislative intent, based policy developments on customary practices rather than on scientific or evidence-based principles, did not adequately understand opioid dosing parameters, or applied disciplinary measures based on faulty and outdated information. He resolved that such developments were to be expected because the membership of state medical boards rarely included experts in palliative care, and board members rarely seek out input on such matters.

The PPSG (2006) identifies eight such policies that can impede the provision of pain management. While each of these policies appears to limit the provision of pain management significantly, we resolve that four of these are more explicitly linked to impeding the provision of pain management at the bedside at the end of life. These particular policies establish that (a) opioids only can be used as a treatment of last resort rather than as a common tool in medical practice, (b) opioids fall outside the boundaries of legitimate medical practice, (c) the amount of physician discretion in prescribing pain medications should be limited, and (d) physicians are required to file a report each time they prescribe opioids for pain management. The other negative policies seem more relevant to substance-abuse issues and less pertinent to EOL care. They categorize the prescription of all opioids as a form of addiction treatment, limit the number of days in which an opioid prescription can be filled, and make other provisions that can impede pain management (e.g., policies that allow pharmacists to refuse filling a pain medication prescription if they deem it is not being used for intended purposes), and create ambiguously stated policies that effectively curtail prescribing practices.

Integrated Model of State Policy Making

Three times in the past six years, PPSG (2000,2003b, 2006) has analyzed states’ medical-board pain-management policy adoptions against these benchmarks. The comparative evaluations confirmed that state medical boards were the primary authority to develop and advance pain-management policies and that state medical-board policy-making activities have increased considerably over the last decade, Still, the PPSG did not find any state that had adopted all eight pain-management–promoting policies and some states had developed policies that impeded pain management. The PPSG resolved that pain-management policies varied substantially from one state to the next and that adopted policies frequently do not comply with current medical knowledge and evidence-based guidelines.

Understanding the factors that precipitate states’ varied pain-management policy adoptions remains deficient. There is little empirical understanding of why some state medical boards adopted policies which have positive impacts on pain management while others developed policies with negative impacts. Following this, we resolved that gaining and transferring an understanding of the formation of these varied state pain-policy outcomes may be useful to researchers who are concerned with further opening the black box of state policy formation and to advocates and policy makers who are most concerned with improving the provision of pain management at the EOL.

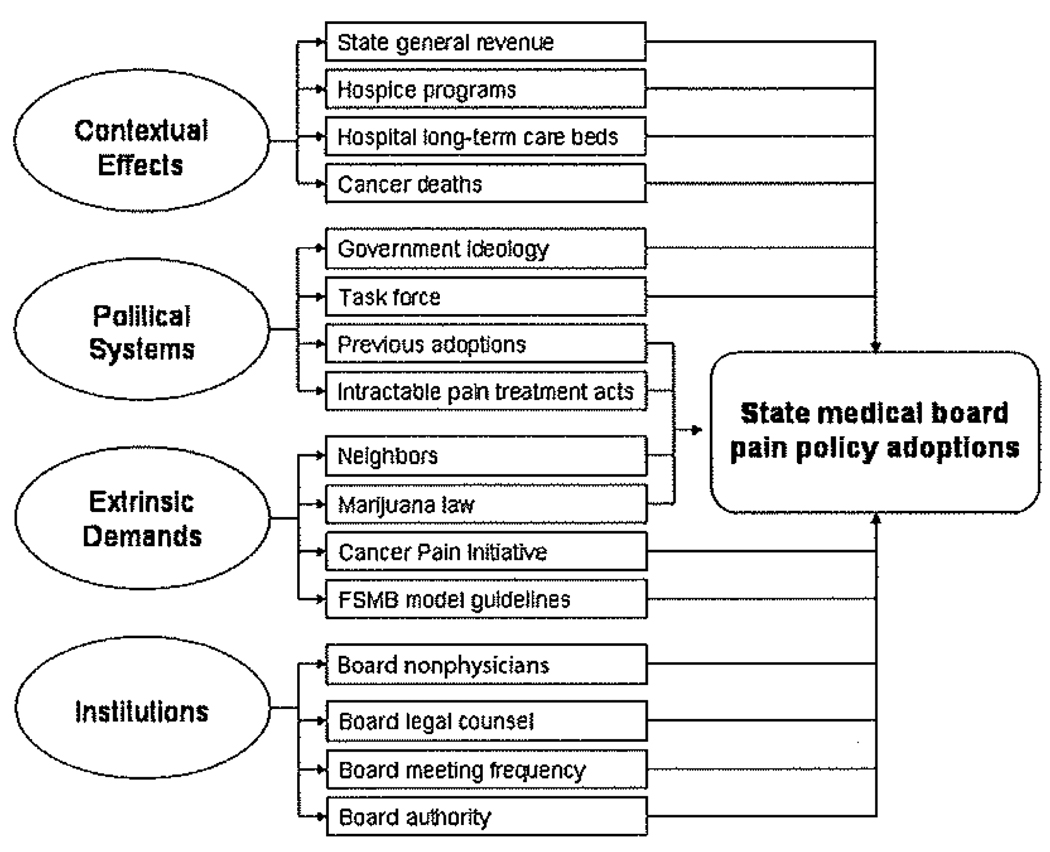

To accomplish this, it was necessary to identify a viable model of policy making that offered a comprehensive account of the policy-making process and could readily be applied to state medical boards. We found the integrated model of policy making most appealing (Ringquist 1993, 1994; Wejnert 2002). This model acknowledges that economic and other contextual effects establish boundaries for policy making and recognizes that these constructs are insufficient for determining public-policy outcomes when considered in isolation. The integrated model accounts for critical characteristics of state political systems as well as external pressures that directly impact policy-making systems. Further, the integrated model incorporates key characteristics of the state policy-making body itself. Kaskie, Knight, and Liebig (2001) adapted the integrated model and found that political system characteristics, extrinsic demands, and institutional variables explained the passage of state legislation targeting older persons with dementia. Grabowski, Ohsfeldt, and Morrisey (2003) applied an integrated model when studying Medicaid expenditures after the repeal of certificate-of-need (CON) requirements and found that CON repeals did not increase Medicaid expenditures in a statistically significant way but that state economic and demographic variables did. In what follows, we consider how sixteen different variables associated with these four factors might influence the policy-making activity of state medical boards (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

State Medical Board Pain Policy Adoptions

Contextual Effects

The research literature has established that state economies assume an influential role on a variety of policy outcomes. However, the effect has not been consistent. In this study, the influence of greater state wealth on pain-management policy adoptions is unclear because medical board policies are not economic in nature but rather consist of regulations that shape and restrain physician practices. Researchers also have found other contextual effects critical in policy formation: states with higher amounts of industrialization and urbanization consistently have developed more policies that pertain to the unique markets within the state (Dye 1975). For example, the highly industrialized states of Michigan and Ohio have a greater number of laws and regulations pertaining to air-pollution control. Following this, it seems quite plausible that market characteristics may be critical to the formation of pain-management policy—states with a greater supply of EOL services, such as hospice programs or long-term hospital beds, may have more policies that pertain to the provision of pain management at the EOL. Problem indicators reflective of the saliency of a particular issue may influence policy action as well (Kingdon 1995; Lester and Lombard 1990). In regard to EOL policies, the annual number of cancer deaths may correspond with a predictable need to combat pain at the EOL because of its connection to cancer morbidity and mortality (Joranson et al. 1992).

Political Systems

Dye (1966) determined that economic and market supply variables were not the only important variables for explaining policy outcomes, but that political system variables mattered as well. For example, states with a liberal ideology tend to enact more policies that respond to social problems compared to those states with a more conservative ideology (Nice 1984). Regarding pain management, the relationship between partisanship, ideology, and pain policies was not as obvious, because this issue historically has received little attention from either party. Another critical feature of state political systems consists of task forces and study groups. A task force can be established by the legislature or governor to define problems surrounding the undertreatment of pain and assess whether current policies are adequate and aligned with best practices for pain management. Policy precedent also is an important aspect of the political system, because prior policy-making activity plays a significant role in explaining contemporary policy-making activity (Khator 1993), Moreover, pain-management issues can be intermittently addressed by other state institutions (e.g., state legislatures). It is important to account for the actions taken through other intrastate policy-making bodies, because they may affect the policy-making outcomes of state medical boards.

Extrinsic Demands

Extrinsic demands on policy decisions manifest in a variety of ways. For instance, diffusion of policy activity via social learning is referred to as the “neighborhood effect.” A recent EOL policy case demonstrates this sort of neighborhood effect. After the Terri Schiavo case in Florida, a flurry of policy activity was observed as state policies diffused across states seeking to avoid similar situations (FindLaw 2005). A similar carryover effect may emanate from related intrastate policy initiatives. For example, state medical marijuana policies may be readily transferred as a way to develop other pain-management policies (Sharp and Johnson 2004).

Another extrinsic demand may derive from the influence of an interest group or federal agency. The earliest and most consistent voice advocating for pain management came from cancer pain initiatives (CPIs) organized by clinicians, patients, and families struggling with cancer-related pain (Dahl and Joranson 1992). Further, the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB), the leadership body of state medical boards, created and distributed to the states the Model Guidelines for the Use of Controlled Substances for the Treatment of Pain (Joranson and Gilson 2003).

Institutions

Policy outcomes adopted by an institution are influenced by characteristics of that institution (Savage 1985). The capacity and strength of the institution in terms of staff qualifications, skills, and professionalism have been shown to affect policy decisions (Khator 1993; Sharp and Johnson 2004), and these characteristics exert considerable influence even if contextual, political, and other external forces are prominent (Ringquist 1993). As such, the structure of state medical boards may be a key to understanding pain-policy outcomes. The composition of board members (e.g., private citizens, nonphysicians) is assumed to have a unique impact on the development of policies. The frequency of board meetings is important because this influences the board’s ability to perform its policy and administrative functions, which should improve the board’s ability to address both medical-practice and drug-regulation policy issues. Further, the amount of formal authority ascribed to the board may help explain the type of policy decisions made.

Research Objective

The main objective of this research was to determine how well an integrated model explained the variation across state medical board pain-management policy adoptions. In particular, we created sixteen independent variables reflective of the four primary factors featured in the integrated model of state policy making. Next, we conducted a series of event-history analyses to determine how well the integrated model explained the formation of eight different types of pain-management policies (four positive and four negative) by state medical boards. To our knowledge, this constituted the first empirical examination of state-medical-board policy making.

Methods

Design

An event-history analysis was applied to fifteen years of annual time-series data for each of eight state pain-policy outcomes from 1988 through 2002. Beginning in 1989, states began creating pain policies aligning with the more contemporary conceptualization of pain management (Gilson, Maurer, and Joranson 2005). Therefore, in order to address temporal sequencing, 1988 was selected as the starting point for this study. Additionally, the fifteen-year period of annual observations was sufficient for detecting patterns and correlates with the adoption of pain-policy provisions by state medical boards (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones 2004).

Sample

Each of the fifty United States was examined, and the units of analysis were the state-years of pain-policy adoption over the fifteen-year period. This created an initial sample population of 750 observations for each pain-policy outcome. However, in an event-history analysis such as this, individual states were removed from the observed sample pertaining to each policy outcome after the state adopted that policy. As such, individual sample sizes for the eight models varied. Final sample sizes are reported in the results section.

Data Sources

Outcomes data for this study are collected from the PPSG (2003a) state pain-policy database and verified by comparing with the American Society of Law, Medicine, and Ethics pain-policy database. We model four positive and four negative policy outcomes most explicitly linked to the provision of pain management at the bedside at the EOL. These include (a) pain management is part of general medical practice, (b) opioids are a legitimate form of professional practice, (c) dosage amount alone does not determine prescription legitimacy, (d) reducing physicians’ fears of regulatory scrutiny, (e) opioids only can be used as a treatment of last resort rather than as a common tool in medical practice, (f) opioids fall outside the boundaries of legitimate medical practice, (g) the amount of physician discretion in prescribing pain medications should be limited, and (h) practitioners are subject to undue prescription reporting requirements. The adoption of each of these pain policies is defined as an outcome of interest, and each policy is measured discretely based on its year of adoption from 1988 through 2002. Given the observed variation across state medical boards, we assume that the eight policy outcomes are independent from each other, and this necessitates that we apply the explanatory model to each outcome and determine if similar or unique events explained the adoption of each outcome.

Predictor Variables

We assume economics and contextual effects, political systems, extrinsic demands, and institutional characteristics shaped the policy-making outcomes, and we identify sixteen predictor variables to represent these four factors. Data used to measure predictor variables come from a variety of sources including the Area Resource Files (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS] 2007) and the U.S. Census Bureau (1984–2003), as well as researchers and advocacy efforts including Berry et al. (1998), cancer pain initiatives, the FSMB (1986–2003), and the PPSG (2000, 2003a, 2006). Twelve predictor variables are entered contemporaneously, and the remaining four variables are lagged to more accurately reflect the nature of their influence on policy making and to accomplish the temporal sequencing necessary for causal inferences (Yamaguchi 1991). Descriptive statistics pertaining to the sixteen variables included in the integrated model of state policy formation are provided (see tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Policy Predictors: Descriptive Statistics for Continuous Variables over All State Years (1988–2002)

| Variable | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State general revenue (per capita) | 3441.15 | 1749.72 | 879.00 | 15711.00 |

| Hospice programs | 32.94 | 23.92 | 2.00 | 101.00 |

| Hospital long-term care beds | 2534.00 | 3160.90 | 93.00 | 16317.00 |

| Cancer deaths per 10,000 deaths | 200.81 | 32.59 | 83.50 | 263.50 |

| Government ideology | 49.38 | 24.68 | 0.00 | 97.92 |

| Previous adoptions | 0.67 | 1.45 | 0.00 | 6.00 |

| IPTA | 0.45 | 1.16 | 0.00 | 6.00 |

| Neighbors | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Medical-board nonphysicians | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.56 |

| Medical-board legal counsel | 1.15 | 1.93 | 0.00 | 12.00 |

| Medical-board meeting frequency | 8.13 | 4.19 | 2.57 | 24.00 |

Table 3.

Policy Predictors: Descriptive Statistics for Categorical Variables over All State Years (1988–2002)

| Variable | Present | Not Present |

|---|---|---|

| Task force | 55 | 659 |

| Marijuana law | 28 | 686 |

| Cancer Pain Initiative | 355 | 359 |

| Federation of State Medical Boards model guidelines | 170 | 544 |

| Medical board authority | 524 | 190 |

Contextual Effects

State revenue, a time-dependent continuous measure of total general revenue in millions of dollars (and reported per capita), is used to capture the influence of the state economy on policy outcomes (U.S. Census Bureau 1987–2003). Entry of these continuous data is lagged such that policy adoption is explained by the previous year’s general revenue. Measures of the possible market effects include the number of hospice programs in each state and the number of long-term care hospital beds (DHHS 2007). The number of deaths per one hundred thousand state residents from malignant neoplasms (i.e., cancer deaths) is a time-dependent continuous variable reflecting the state demographic effect (U.S. Census Bureau 1987–2003). Data are entered in a lagged fashion because it is anticipated that policy adoption was influenced by data from the previous year’s cancer death rates, given the lag time typical with both collecting and reporting this type of data.

Political Systems

The measure of state political ideology is based on interest-group ratings of elected officials, election returns for congressional races, the party composition of state legislatures, and the party affiliation of state governors (Berry et al. 1998). This variable is defined as a time-dependent continuous measure. A time-dependent dichotomous variable called “task force” is included to indicate the presence of a government-initiated (administrative or legislative) task force, commission, or work group on pain management or palliative care. This measure is developed from information provided by the American Academy of Pain Medicine and American Pain Society (1996), the American Bar Association Commission on Legal Problems of the Elderly (2002), the Partnership for Caring (2001), and the National Conference of State Legislatures (1999–2003). The number of previously adopted pain-management–enhancing policy provisions also is entered into the models. This measure indicates whether or not the state medical board made a policy adoption that contained some but not all of the possible pain-management–enhancing provisions. Data used to create this measure are collected from the PPSG state pain-policy evaluation reports (PPSG 2003a). The next variable is a time-dependent count variable indicating the number of pain-related provisions found in IPTAs as well as CSAs and medical practice acts (MPAs). This variable captures the interest within the state legislatures to address pain-management issues. Data come directly from the PPSG state pain-policy database (2003a).

Extrinsic Demands

The variable “neighbors” is modeled as a time-dependent variable reflecting policy diffusion and measures the proportion of total possible border states that adopted pain-management policies in preceding years. It is entered in a lagged fashion because it is conceivable that other states current work on a pain policy may impact another state’s decisions in the following year (Berry and Berry 1990). State medical marijuana policy serves as a time-dependent dichotomous variable that indicates the legality of the use of medicinal marijuana to treat pain and other medical conditions (Marijuana Policy Project 2004). While several states have passed laws since 1978 that were favorable to medicinal marijuana use, early policies were largely symbolic. Starting with California’s policy adoption in 1996, some states began to adopt more substantial medical marijuana policies with strengthened patient and clinician safeguards. For 1996 and beyond, state-years are coded as “1” for the existence of an effective medical marijuana policy.

The status of each state’s CPI is a time-dependent dichotomous variable that indicates whether or not the interest group was active in each year of this study (American Alliance of Cancer Pain Initiatives [AACPI] 2004). Data on the origination and status of CPIs in the states come directly from vital records maintained by the AACPI. The presence of model guidelines for state pain policy, as created and distributed by FSMB—“FSMB model”—serves as a time-dependent dichotomous variable that indicates the creation, distribution, and continued presence of these guidelines to the states (FSMB 2004). The guidelines were distributed to all states in July 1998 and are assumed to effect board policy decisions in 1999 and beyond because of their continued presence on the FSMB Web site and periodic recirculation to boards. Given the lack of variability across the states for this variable, the results of early model-building stages will determine its utility in final models.

Institutional Characteristics

Nonphysician medical-board members represent the role of medical-board structure on its policy adoptions and account for the presence of other health professionals and public citizens on state boards. This is a time-dependent proportion of physician to non-physician members, and data are taken from the FSMB “Exchange Section 3” series (1986–2003). A second measure for medical-board capacity reflects the expected influence that legal counsel had on medical boards. This time-dependent variable is represented as the number of full-time legal counsel on the medical board (ibid.). A third measure of board capacity is defined as the number of regularly scheduled medical-board meetings per year (ibid.). A final variable reflects the policy-making authority of the medical board. Boards with the highest level of policy making authority are coded as “1” and “0” for levels of less authority (ibid.).

Analysis

State medical-board policy adoptions are evaluated with an event-history analytical technique using Cox semiparametric regression. This technique generates hazard rates—applied here as the instantaneous risk that a medical board would adopt a pain-management policy at a given time, conditioned by the fact that a state had not previously adopted that policy. Coefficients are measured in terms of the hazard rate such that a positive coefficient indicates that the hazard is increasing as a function of the covariate (i.e., the likelihood that the board would adopt the policy increased), while a negative coefficient indicates the hazard is decreasing as a function of the covariate (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones 2004). For each of the pain-policy outcomes, the basic structure is:

Where X1(t-1), X2(t) X3(t) X4(t-1) represented the contextual effects of the state economy, market supply of hospice program and hospital long-term care beds, and demographic effect measured as number of cancer deaths; X5(t), X6(t), X7(t), X8(t) represented the political system variables government ideology, task-force activity, previous policy adoptions, and other legislative activity; X9(t-1), X10(t), X11(t), and X12(t) represent the extrinsic-demands variables capturing the neighbor effect, intrastate medical marijuana laws, the impact of cancer interest groups, and federal medical-board guideline provisions; and X13(t), X14(t),X15(t), and X16(t) represent the institutional characteristics of the medical boards’ membership, structure, and meeting frequency. To achieve nonredundant and parsimonious final models for each outcome, we begin with theoretically driven, manually built models, and our final models are derived by a backward mapping technique in which variables are deleted one by one from each model, until only the variables that produced p-value statistics equal to or less than a probability of 0.15 remain in the model. Given the novelty of quantitative research on pain-management policy adoptions by state medical boards, this approach serves to validate the theoretically-driven model and raise confidence surrounding statistical results. All statistical analyses are performed using SAS 9.1 from SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina, United States (2005).

Results

Over the fifteen-year period, nineteen states adopted all four positive pain-management policies, no state had adopted all four of the negative outcomes, and ten states adopted none of the eight outcomes (see table 4). The most common policy adoption (n = 30) established that opioids were a legitimate form of professional practice (Outcome B), and the least common policy (n = 4) stated that opioids fall outside the boundaries of legitimate medical practice (Outcome F). State medical boards sometimes adopted policy outcomes individually (e.g., Ohio adopted Outcome D in 1995 and did not adopt any others during the study period, while Mississippi adopted Outcome A in 1997 and Outcome B in 1999, but it never adopted outcomes C and D). In many cases, two or more outcomes were adopted as part of a larger, comprehensive pain policy (e.g., California adopted all four positive outcomes within one broad medical board statement in 1994). Early in the study period, states were more likely to adopt one or a few policies. However, multiple policies were increasingly adopted in the same year—both independently and as a part of a more encompassing policy—during the middle and later years of this study.

Table 4.

States’ Adoptions of Eight Pain-Policy Outcomes

| State | Policy A (+) |

Policy B (+) |

Policy C (+) |

Policy D (+) |

Policy E (−) |

Policy F (−) |

Policy G (−) |

Policy H (−) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | ||||

| AK | ||||||||

| AZ | 1997 | 1997 | 1997 | 1997 | 1997 | |||

| AR | 1997 | 1997 | 1997 | |||||

| CA | 1994 | 1994 | 1994 | 1994 | 1994 | |||

| CO | 1996 | 1996 | 1996 | 1995 | ||||

| CT | ||||||||

| DE | ||||||||

| FL | 1999 | 1999 | 1999 | 1999 | ||||

| GA | 1991 | 1992 | 1992 | |||||

| HI | ||||||||

| ID | 1995 | 1995 | 1995 | |||||

| IL | ||||||||

| IN | ||||||||

| IA | 1997 | 1997 | ||||||

| KS | 1998 | 1998 | 1998 | 1998 | ||||

| KY | 2001 | 2001 | 1996 | 2001 | 1996 | 1996 | ||

| LA | 2000 | 1997 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | |||

| ME | 1999 | 1999 | 1999 | |||||

| MD | 1996 | |||||||

| MA | 1989 | 1989 | 2001 | 2001 | ||||

| MI | ||||||||

| MN | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | ||||

| MS | 1997 | 1999 | 1996 | |||||

| MO | 2001 | 2001 | 2001 | 2001 | ||||

| MT | 1996 | 1996 | 1996 | |||||

| NE | 1997 | 1999 | 1999 | 1999 | ||||

| NV | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | ||||

| NH | ||||||||

| NJ | 1997 | 1997 | 1997 | |||||

| NM | 1996 | 1996 | 1996 | 1996 | ||||

| NY | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | |||||

| NC | 1996 | 1996 | 1996 | |||||

| ND | ||||||||

| OH | 1995 | 1995 | ||||||

| OK | 1999 | 1999 | ||||||

| OR | 1999 | |||||||

| PA | 1998 | 1998 | 1998 | 1998 | ||||

| RI | 1995 | |||||||

| SC | 1999 | 1999 | 1999 | 1999 | ||||

| SD | 1999 | 1999 | 1999 | 1999 | ||||

| TN | 1999 | 1999 | 1995 | 1999 | 1995 | 1999 | 1995 | |

| TX | 1993 | 1993 | 1993 | 1995 | ||||

| UT | 1999 | 1999 | 1999 | 1999 | ||||

| VT | 1996 | 1996 | ||||||

| VA | 1998 | 1998 | ||||||

| WA | 1999 | 1996 | 1999 | 1996 | ||||

| WV | 2001 | 1997 | 2001 | 1997 | 1997 | |||

| WI | ||||||||

| WY | 1996 | |||||||

| Total | 27 | 30 | 24 | 28 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 7 |

Positive Pain-Policy Adoptions

The final model for Outcome A (pain management is part of medical practice) includes a total of 639 observations, twenty-seven adoptions, and five predictor variables that satisfy the model fit criterion. The number of legal counsel on the medical board provides the strongest positive impact (hazard rate [HR] 1.33; confidence interval [CI] 1.05–1.72), while previous adoptions have the strongest negative influence (HR 0.53; CI 0.31–0.90). The number of hospital long-term care beds exerts a slight but nonsignificant positive influence, while state revenue and the total number of board meetings exert slight but nonsignificant negative effects. Results are displayed in table 4.

The final model for Outcome B (opioids are a legitimate form of professional practice) includes 619 observations, thirty adoptions, and four predictor variables that satisfy the model fit criterion (see table 5). The number of legal counsel on the medical board provides the strongest positive impact (HR 1.34; CI 1.04–1.73), while previous adoptions have the strongest negative albeit nonsignificant influence (HR 0.47; CI 0.22–1.00). The number of long-term care beds exerts a slight but nonsignificant positive influence, while state revenue exerts a slight but nonsignificant negative effect.

Table 5.

Multivariable Models of State Pain-Enhancing Policy Adoptions

| Predictor | Policy A (+) | Policy B (+) | Policy C (+) | Policy D (+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State general revenue (per capita) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00)* | |||

| Hospital long-term care beds | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | ||

| Government ideology | 0.98(0.97–1.00)* | |||

| Previous adoptions | 0.55 (0.32–0.93)** | 0.47 (0.22–1.00)* | 0.41 (0.21–0.80)*** | 0.59 (0.36–0.97)** |

| Marijuana law | 2.66 (0.86–8.38)* | |||

| Medical board legal counsel | 1.43 (1.12–1.82)*** | 1.41 (1.10–1.79)*** | 1.44(1.13–1.83)*** | 1.67(1.34–2.09)*** |

| Medical board meeting frequency | 0.91(0.82–1.01) | 0.90 (0.81–0.99)** | ||

| Observations/events | 639/27 | 619/30 | 640/26 | 636/28 |

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

The final model for Outcome C (dosage amount alone does not determine prescription legitimacy) includes 640 observations, twenty-four adoptions, and four predictor variables that satisfy the model fit criterion (see table 5). The number of legal counsel on the medical board provides the strongest positive impact (HR 1.44; CI 1.13–1.83) while previous adoptions have the strongest negative significant influence (HR 0.41; CI 0.21–0.80). The number of long-term care beds and the passage of a medical marijuana law exert slight but nonsignificant positive influences.

The final model for Outcome D (reducing physicians’ fears of regulatory scrutiny) includes 636 observations, twenty-eight adoptions, and four predictor variables that satisfy the model fit criterion (see table 5). The number of legal counsel on the medical board provides the strongest positive impact (HR 1.67; CI 1.35–2.09) while previous adoptions have the strongest negative significant influence (HR 0.59; CI 0.36–0.97). The number of board meetings also exerts a significant negative influence (HR 0.90; CI 0.81–0.98) while the government ideology exerts a slight but nonsignificant negative influence.

Negative Pain-Policy Adoptions

The model for negative Outcome E (opioids only can be used as a treatment of last resort) includes a total of 657 observations, ten adoptions, and does not meet goodness-of-fit criterion. We suspect that the small number of events (only ten states passed Policy E) contributes to the large standard errors and lack of fit. Univariate analysis indicates that the neighbor effect exerts a positive influence and government ideology exerts a slight negative influence.

The final model for Outcome F (opioids fall outside the boundaries of legitimate medical practice) includes a total of 699 observations, four adoptions, and does not meet goodness-of-fit criterion for the same reasons discussed previously. The univariate analysis suggests that the presence of a task force exerts a slight positive influence and that previous adoptions exert a negative influence.

The final model for Outcome G (the amount of physician discretion in prescribing pain medications should be limited) includes a total of 682 observations, eight adoptions, and results in a lack of fit. The presence of a state task force exerts a slight positive influence.

The final model for Outcome H (physicians are required to file a report each time they prescribe opioids for pain management) includes a total of 674 observations, seven events, and also results in a lack of fit. The univariate analyses indicate that no variables were associated with Outcome H.

Discussion

Multivariable Model Findings

Our analysis confirmed that substantial variation in pain-management policies exists from one state to the next. On one hand, we could conclude that the glass is half empty because less than 40 percent of all states adopted the four positive pain-policy provisions studied here and more than 20 percent of states adopted none. On the other hand, we could just as easily resolve that the glass is half full because 80 percent of the states developed at least one of the positive pain-management provisions and the number of states that upheld policies impeding the provision of pain management (i.e., negative policies) was much lower than expected. Moreover, although we gained relatively fewer insights by examining the infrequent adoption of negative pain-policy outcomes, our evaluations of the positive outcomes confirmed that all four of them assume significant roles in state medical-board policy formation, and that there are both common and unique influences on the adoption of positive pain policies.

Contextual Effects

The lack of strong and significant associations between state revenue, hospital long-term care beds, hospice programs, cancer deaths, and pain policies suggests that medical boards operate independently from these economic, market, and demographic influences. Medical boards in wealthy states were just as likely as less wealthy states to pass pain policies; and, similarly, there were no differences in policy passage for boards in states with large or small numbers of hospital long-term care beds, hospice programs, or persons who died with cancer. Because medical boards are often designated as independent bureaus that are not subject to electoral cycles, they may not have to be as responsive to contextual indicators as other executive or legislative policy-making bodies are.

It also may be that the relationship between the state economy, market supply of services, demographic indicators, and medical-board pain-policy outcomes may not be so straightforward as to be captured by an evaluation of direct effects. Lammers and Klingman (1984) argued that such contextual variables more likely have a moderating or mitigating effect on policy making. They impact political-system or institutional variables, which in turn may have more direct effects on particular policy outcomes. Although we did not test for such paths in this research, our multivariable model testing supported this assertion as the inclusion of these contextual variables appeared to mitigate relationships between other variables and pain-policy outcomes. For example, while we initially found significant univariate associations between extrinsic and systemic variables and pain policies, these relationships were not sustained in multivariable models. This provides further evidence about the utility of testing a fully specified integrated model when trying to understand the state health policy-making process. Not considering the possible indirect (and direct) effects of contextual influences relative to the other factors may result in inaccurate conclusions about the policy making from omitted variable bias.

Political Systems

One of the most significant, albeit negative, influences on positive pain-policy adoptions was the history of pain-policy activity. The more pain policies already adopted by a board, the less likely the board was to adopt another pain policy. This finding was somewhat surprising as previous research (Kaskie, Knight, and Liebig 2001; Mooney and Lee 1995) found that states which initiated a course of health policy making were more likely to continue. In this case, it may be that when the topic of pain management initially presented itself, early adopters had little precedent to base their actions upon and advanced a relatively limited scope of the entire range of pain policies (S. Johnson, personal communication, March 15, 2006). The boards may have resolved that further adoptions of additional pain-management policies were unnecessary.

Rogers (1995) would suggest that such states may have intended to revisit these policies in subsequent years. Glick and Hays (1991) found that many states modified living-will laws over an extended period of time and Mooney and Lee (1995) determined that state abortion policies became more “permissive” over time as well. However, given the extensive range of responsibilities placed upon medical boards and the comparative lack of organized extrinsic or systemic efforts concerning pain policies, it may be that after the initial policies were enacted, pain management was placed at the back of a protracted policy agenda—where it apparently has remained despite any intentions otherwise.

The findings suggest that pain management had not been moved (back) onto medical-board agendas by any sort of crosscutting institutional or ideological interest within the state political systems. We suspect that task forces and legislative enactments would have perpetuated medical-board policy making (Khator 1993; Kingdon 1995). Yet our results indicate that there is no relationship between state task forces, legislative activity, and state medical-board outcomes. The lack of systemic interest in pain-management policies is evidenced further by the lack of a pervasive association between government ideology and the policy outcomes studied here. It was hypothesized that more liberal states would be more likely to address the medical issue of pain management, given their propensity to be more active in social issues and consumer protections (Nice 1984). Only policy Outcome D (reducing physicians’ fears of regulatory scrutiny) is mildly associated with states’ political ideologies.

Extrinsic Demands

The finding that none of the extrinsic demands exerted a statistically significant and favorable impact on medical boards is also surprising. State medical marijuana policies were hypothesized to positively influence pain-policy outcomes because the discussions surrounding the introduction and adoption of medicinal marijuana seemed linked to philosophies for pain management. We find only a modest association between these laws and the passage of board policies concerning the allowed dosage amounts pertaining to pain (Outcome C). We also find no apparent influence of other extrinsic organizations that, theoretically, worked to advance pain-management–enhancing policies. For example, state CPIs and neighboring states did not prove to be statistically associated with board adoptions of any of the policy outcomes.

Given the specific knowledge and technical details surrounding pain management, we suspect that there were few efforts made to advance such a focused policy interest by any one of these extrinsic influences (Longest 1998; Moe 1981). It also is plausible that their efforts were too narrowly targeted to have any carryover effect to state medical-board pain-policy making. A closer inspection of advocacy organizations behind medicinal marijuana legislation, such as the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, suggests that their efforts were targeted toward federal and state legislators more than toward federal or state agency personnel such as state medical-board members (National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws 2006; Marijuana Policy Project 2004). We also examined FSMB activities and resolved that the distribution of model pain-management policy guidelines did not result in boards’ adoption of comprehensive pain policies. Perhaps extrinsic influences were more critical in raising the general level of awareness about pain policy, but heightened awareness, per se, did not equate with medical-board policy adoption.

Institutional Characteristics

Having more legal counselors on the state medical boards was the variable that exerted the strongest and most consistent impact on adopting all four of the positive pain-management policies. Sonnenfeld (2002) would suggest that the skills of legal counselors make them useful to advancing medical-board policy. The American Bar Association Task Force on Corporate Responsibility (2003) recognizes that lawyers could assist with analyzing compliance of pain policies with applicable laws and regulations as well as evaluate the risks associated with practicing pain management. That said, it could be that the extent to which boards had legal counselors as members or staff led to an increase in the board’s ability to conduct policy research and facilitate the translation of medical concepts for pain management into new or updated public-policy language and appropriate legalese to accomplish the intent for physician practice.

Interestingly, the number of annual meetings exerted a negative impact on the hazard for a board to adopt Outcome D, which is in the direction contrary to that hypothesized. It may be that rather than having more time to address policy issues, those boards that met most frequently did so because they were charged primarily with clinical case reviews—the responsibility that often consumes the greatest amount of physician members’ time on the board. For example, in any given year, the California medical board may investigate ten thousand complaints regarding physician practices or omissions (Morrison and Wickersham 1998). As such, the nature of a board’s activity is determined by the demands placed on it, which may include peer evaluations and complaint resolutions more than policy making. In states in which boards meet less frequently the members may have been charged more with having policy dialogue and action during the formal meeting time, including pain-management–enhancing pain-policy adoptions, and charged less with responsibility for medical case reviews during such meetings.

The other two institutional variables (i.e., nonphysician board members and medical board authority) do not significantly influence a board’s decision to adopt any of the outcomes examined in this research. Placing public members on professional licensing boards may have strong symbolic value, but the impact of their participation remains limited (Barger and Hadden 1984). Arguably, nonphysician board members’ understanding of viable public policy responses to the undertreatment of pain may not have been sufficient. Whether or not a state medical board had a high level of autonomy did not appear to significantly drive its pain-policy decisions either. While it might be theorized that more autonomous boards should have a greater capacity to develop pain policies (Sonnenfeld 2002), we observe only a small amount of variability in board authority from one state to the next—by and large, most boards were fully autonomous during some or most years observed.

Utility of Integrated Modeling for Understanding Policy Outcomes

Researchers historically have argued that state policy outcomes were shaped by contextual influences such as the size of the state economy and political systems’ variables such as the ideology of the political majority. Extrinsic influences, such as interest groups, and discrete features of policy-making institutions, such as staff support, were considered secondary or nonessential to the policy-making process. In this research, we follow a growing number of researchers who have expanded this limited conceptualization (Kaskie, Knight, and Liebig 2001; Ringquist 1993, 1994; Wejnert 2002) and verify the utility of a more integrated model based on the premise that several of these types of factors work together in varying combinations. We specifically demonstrate that an integrated model captures the influence of multiple factors on state medical-board pain-policy outcomes. In so doing, we make a step toward further illuminating the black box of state health policy making by avoiding the sort of omitted variable bias that has appeared in much of the previous work. Indeed, after evaluating more than sixty recent studies concerning health policy formation, Miller (2005) resolved that most researchers continue to fall short with their explanations because they often test models that only account for economic, market supply, and other readily obtainable variables; these researchers consistently omit important political-system characteristics, extrinsic influences, and institutional effects that, as shown here, have significant impacts on health policy making.

This research also features several unique constructs that have strong and specific theoretical relationships with pain-management policies. For example, we identified four characteristics of state medical boards that have plausible associations with pain-management policy outcomes and then gathered data to measure these constructs. In making this effort to identify and measure more exact causal mechanisms, we can say much more than “it’s the institution, stupid” when discussing the relationship between predictor variables and policy outcomes (Steinmo and Watts 1995). Here, we learn how policy outcomes correspond (or not) with particular aspects of the policy-making institution, including autonomy, membership, and meeting frequency.

If we followed on previous research and included only variables that were readily obtainable from secondary data sets, we would have subjected ourselves to additional limitations. Research designs which feature such gross variables lack a certain amount of face validity. After all, how state revenues or other general constructs actually impact state medical-board outcomes is unknown, and findings about such variables may face limitations in practical utility, as they do in this study. For example, modifying a state’s budget likely will not lead to an increase in the formation of pain-management policies. It is more likely that state health policies are the product of both general and specific effects, and gross variables exert a moderating or mitigating effect on more specific cause and effect mechanisms (Lammers and Klingman 1984). By making an effort to measure more precise causal mechanisms of state pain-management policy outcomes and then test their influence relative to contextual effects, we generate more plausible and readily applicable insights.

A more complex depiction of state health policy outcomes was another major step taken in this research. In testing the formation of eight discrete types of medical-board pain policies rather than just one gross construct, we join scholars who assert that policy outcomes rarely are one dimensional and should not be measured as a dichotomous dependent variable such as whether or not a state adopts a policy (e.g., certificate of need) (Boehmke 2006). In contrast, these researchers depict policy outcomes as having component parts that are shaped variably by different factors and unique determinants. For example, instead of examining whether or not a state adopted a general antismoking law, Shipan and Volden (2004) examined the adoption of three possible types of antismoking laws with uniquely specified models. In this research, we provide a more complete depiction of state health policy responses to patients’ clinical pain by examining both positive and negative outcomes, and this leads to a more informative depiction of pain-management policy formation.

Implications

Much work remains to advance the public-policy response to the under-treatment of pain. Twelve state medical boards have not yet adopted any of the pain-management–enhancing policies, and no state has adopted them all (PPSG 2003a). In addition, many existing state pain policies are not consistent with current recommendations for evidence-based clinical and organizational practice (Field and Cassel 1997; PPSG 2003a). So how exactly can efforts be directed to expand and update pain policies?

One particular direction supported by this research is that pain-policy proponents, be they external interest groups and advocates (e.g., CPIs, state hospice associations, or EOL care providers) or state policy makers (e.g., attorneys general, governors, task forces and agency staff, legislators and their staff, or medical-board members themselves) should focus efforts toward encouraging state boards to include legal counselors because this variable proved such a strong determinant of pain-policy outcomes (i.e., for every increase in one full-time legal counselor the hazard that the board would adopt Outcomes A though D increases by a minimum of 44.3 percent).

Moreover, given the pervasive need to expand and update pain policies, efforts should be directed toward educating boards about current evidenced-based practices for clinical and organizational approaches to pain management. Perhaps the most effective way to accomplish this direction is to increase awareness of the recently developed FSMB model guidelines among state medical boards, perhaps via the offering of a national conference or opportunities for boards to consult directly with the FSMB, either of which would require a minimal amount of effort.

Advocacy efforts must also be directed to states that previously adopted pain policies that are outdated or less than comprehensive. This research shows that expanding and updating pain policies may be especially challenging in states that have already made some effort to address the management of pain (i.e., the hazard for adopting outcomes A through D decreases by at least 45 percent in states in which a pain policy had been adopted). Therefore, efforts might be directed toward increasing the engagement of extrinsic influences including CPIs, National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, and provider associations dedicated to advocating pain management and EOL care specifically. Such efforts should focus on state medical boards and requesting that the boards (re-)visit previously adopted pain policies to expand and update them as needed. Haywood and Nordin (1997) found that changes in policy or practice guidelines coincided with changes in provider behavior or incentives. Perhaps states could follow California’s lead and adopt policies that mandate continuing education for physicians on pain-management techniques for terminally ill patients (Medical Board of California 2001).

Further, some attention might be directed toward increasing the influence of state political systems. The Oklahoma attorney general, Drew Edmondson, initiated an effort among the National Association of Attorneys General (2002) to update legislative policies related to advance directives and pain management for the dying. Continued or related efforts are needed within this (Edmondson 2006) and similar associations representing state public officials so they can assist legislatures and medical boards to develop and update pain policies (FSMB 2004; PPSG 2003b).

Directions for Future Research

Our analysis of eight state medical board pain policies is just one possible conceptualization of a state pain-policy outcome. Future research might look at the formation of other legislative, executive, or judicial policies pertaining to pain management (Imhof and Kaskie 2007). Evaluating a broader range of state policy outcomes would allow researchers to determine the relative interplay among the policy-making authorities within state governments. Future research also could find other variables to include in the explanatory model. For example, researchers might include a measure of the influence of the Roman Catholic Church on pain-policy adoptions, because this institution has historically impacted other EOL-related policies (Hays and Glick 1997). Further, it would be important to create a more nuanced depiction of the roles that were played by the CPIs and other extrinsic forces. Following Kaskie, Knight, and Liebig (2001), researchers might account for the specific actions taken by the interest groups (e.g., how many lobbying activities were pursued, how many bills were introduced) rather than marking whether or not an interest group was active.

Moreover, using the Cox model was just one of many statistical approaches available. Future researchers might consider conducting more complex duration models such as a conditional gap-time duration model with variance correction to account for multiple pain-policy adoptions or modifications over the years within a state (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones 2004). This approach might provide additional information regarding the hazards for updating a policy or different influences on first versus subsequent adoptions. Another analytic approach would be to test a structural equation model to confirm the appropriateness of the integrated theory and test more specific, time-sensitive paths of policy formation (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001).

Still, quantitative approaches can only generate a finite number of insights. Future research also must consider the qualitative components of pain-management policy formation. Now that it has been established that board pain policies are important and that board characteristics impact their policy adoptions, more information about the actual policy-making processes that take place across state medical boards is warranted. A mixed-methods study could capture and capitalize upon available qualitative data regarding pain-management advancement efforts and enrich the existing quantitative findings (Babbie 2001; Creswell 2003). For instance, interviewing medical board members or reviewing meeting minutes might provide unique insights not afforded by quantitative analyses.

Finally, future research must test the underlying assumption that public health policies provide the legal structure that shapes organizational, clinical, and individual pain-management practices. What may be more important than the adoption by a medical board of a pain policy is whether the passage of the policy actually improved the undertreatment of pain. Therefore, it is not sufficient to determine solely if and how a pain policy was adopted, but one also needs to determine whether its implementation was successfully completed as intended. Do state medical board pain policies have the intended effect of improving patient outcomes?

Although the application of further and more complex analytical approaches to this policy issue will be important to developing our understanding of pain-policy adoption across the United States, Spitz and Abramson (2005) caution that holding back efforts to advance public policies may be unwarranted. While research can inform discussions about what should or should not be done, we agree with Spitz and Abramson that the inevitable lack of conclusiveness of any particular research study can contribute to the perpetuation of the status quo.

Conclusions

Many of the previous analyses of health policy formation have fallen short on two points. First, most of these efforts have observed a single policy outcome and have drawn conclusions based on the power of deduction. Second, the analyses that have relied on empirical analyses often have failed to apply a comprehensive model to a policy outcome defined by component parts rather than a one-dimensional dichotomy. In this work, we advanced previous research efforts that were limited to more general results, thereby affording few insights about specific cause-and-effect mechanisms of unique state health policy outcomes. Moreover, this research focused on a topic of critical importance to chronically and terminally ill patients and their families and to countless professionals and advocates working to improve both the provision of pain management at the EOL. This study provided some insights about how to update and expand state policies that promote the provision of pain management to facilitate a good death experience for all. If the current lack of attention to this issue continues, we can only conclude that public policies will fall even further behind the advancement of evidence-based pain-policy guidelines, and the number of Americans who continue to suffer needlessly in pain at the time of death will only increase.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Keela Herr, Dr. Bridget Zimmerman, Dr. Robert Ohsfeldt, Dr. Frederick Boehmke, and Dr. Susan Johnson for providing excellent guidance to this research effort. We also wish to acknowledge Taylor Heim, research assistant, for his assistance during our manuscript preparation.

Contributor Information

Sara L. Imhof, Concord Coalition

Brian Kaskie, University of Iowa.

References

- American Academy of Pain Medicine and American Pain Society. The Use of Opioids for the Treatment of Chronic Pain: A Consensus Statement. [accessed May 13, 2008];1996 www.ampainsoc.org/advocacy/opioids.htm.

- American Alliance of Cancer Pain Initiatives. State Cancer Pain Initiative’s Initial Development 1986–1996. 2004 Unpublished raw data. [Google Scholar]

- American Bar Association Commission on Legal Problems of the Elderly. End-of-Life Care Legislation Calendar Year 2001. [accessed April 24, 2008];2002 www.abanet.org/aging/legislativeupdates/home.shtml.

- American Bar Association Task Force on Corporate Responsibility. Report of the American Bar Association Task Force on Corporate Responsibility. Business Lawyer. 2003;59(1):145–187. [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association. Position Statement: Pain Management and Control of Distressing Symptoms in Dying Patients. [accessed April 24, 2008];2003 nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/HealthcareandPolicylssues/ANAPositionStatements/EthicsandHumanRights.aspx.

- Associated Press. Washington Post: 2005. Mar 21, The Battle for Terri Schiavo. [Google Scholar]

- Babbie E. The Practice of Social Research. 9th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barger D, Hadden SG. Placing Citizen Members on Professional Licensing Boards. Journal of Consumer Affairs. 1984;18(1):160–170. [Google Scholar]

- Berry RS, Berry WD. State Lottery Adoptions as Policy Innovations: An Event History Analysis. American Political Science Review. 1990;84:395–415. [Google Scholar]

- Berry W, Ringquist E, Fording R, Hanson R. Measuring Citizen and Government Ideology in the American States, 1960–1993. American Journal of Political Science. 1998;42:327–348. [Google Scholar]

- Boehmke F. Approaches to Modeling the Adoption and Modification of Policies with Multiple Components. Paper presented at the Midwest Political Science Association Annual Meeting; April 20, 2006; Chicago, IL. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Box-Steffensmeier JM, Jones BS. Event History Modeling: A Guide for Social Scientists. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Buzzee SEM. The Pain Relief Promotion Act: Congress’s Misguided Intervention into End-of-Life Care. University of Cincinnati Law Review. 2001;70:217–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byock I. Dying Well: Peace and Possibilities at the End of Life. New York: Riverhead Books/Putnam; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Compassion in Dying Federation. Legal Advocacy: Center for End of Life Law and Policy. [accessed January 25, 2005];2005 www.compassionindying.org/legal.php. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Method Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl JL, Joranson DE. Cancer Pain: The U.S. Responds. Palliative Medicine. 1992;6:94–97. [Google Scholar]

- Dye T. Politics, Economics, and the Public: Policy Outcomes in the American States. Chicago: Rand McNally; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Dye T. Population Density and Social Pathology. Urban Affairs Review. 1975;11:265–275. doi: 10.1177/107808747501100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson WAD. Policy Barriers to Pain Control. In: Doka KJ, editor. Pain Management at the End of Life: Bridging the Gap between Knowledge and Practice. Washington, DC: Hospice Foundation of America; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Federation of State Medical Boards. Legislative and Regulatory Exchange. Dallas: Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States, Inc.; 1986–2003. [Google Scholar]

- Federation of State Medical Boards. Development of the Model Policy for the Use of Controlled Substances for the Treatment of Pain. 2004 May; www.fsmb.org/pdf/2004_grpol_Controlled_Substances.pdf.

- Federation of State Medical Boards. [accessed April 24, 2008];What Is a State Medical Board? 2005 www.fsmb.org/memberboards.html.

- Field MJ, Casse CK, editors. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FindLaw. Terri Schiavo Case: Legal Issues Involving Healthcare Directives, Death, and Dying. [accessed April 27, 2005];2005 news.findlaw.com/legalnews/lit/schiavo/ [Google Scholar]

- Fishman SM. Pushing the Pain Medicine Horizon. Pain Medicine. 2005;6:280–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galusha BL. The Role of Medical Licensing and Disciplinary Boards. Quality Assurance Utilization Review. 1988;3(3):66–70. doi: 10.1177/0885713x8800300302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber BJ, Teske P. Regulatory Policymaking in the American States: A Review of Theories and Evidence. Political Research Quarterly. 2000;53:849–886. [Google Scholar]

- Gilson AM, Maurer MA, Joranson DE. State Policy Affecting Pain Management: Recent Improvements and the Positive Impact of Regulatory Health Policies. Health Policy. 2005;74:192–204. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick HR, Hays SP. Innovation and Reinvention in State Policymaking: Theory and the Evolution of Living Will Laws. Journal of Politics. 1991;53:835–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon DB, Berry PH, Dahl JL. JCAHO’s New Focus on Pain: Implications for Hospice and Palliative Care Nurses. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing. 2000;2:135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski DC, Ohsfeldt RL, Morrisey MA. The Effects of CON Repeal on Medicaid Nursing Home and Long-Term Care Expenditures. Inquiry. 2003;40:146–157. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_40.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen PS. Prescribing Opiates for Pain Relief. Minnesota Medicine. 2000;83(5):57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays SP, Glick HR. The Role of Agenda Setting in Policy Innovation: An Event History Analysis of Living-Will Laws. American Politics Quarterly. 1997;25:497–516. [Google Scholar]

- Haywood KJ, Nordin M. Low Back Pain Assessment Training of Industry-Based Physicians. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 1997;34:371–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CS., Jr The Negative Influence of Licensing and Disciplinary Boards and Drug Enforcement Agencies on Pain Treatment with Opioid Analgesics. Journal of Pharmaceutical Care in Pain and Symptom Control. 1993;1(1):43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Imhof S, Kaskie B. Gerontologist. 2007. How Can We Make the Pain Go Away? Public Policies to Manage Pain at the End of Life. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: JCAHO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Joranson DE. Intractable Pain Treatment Laws and Regulations. American Pain Society Bulletin. 1995;5(2):15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Joranson DE, Cleeland CS, Weissman DE, Gilson AM. Opioids for Chronic Cancer and Noncancer Pain: A Survey of State Medical Board Members. Federation Bulletin. 1992;79(4):15–49. [Google Scholar]

- Joranson DE, Gilson AM. Legal and Regulatory Issues in the Management of Pain. In: Graham AW, Schultz TK, Mayo-Smith M, Ries RK, Wilford BB, editors. Principles of Addiction Medicine. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2003. pp. 1465–1474. [Google Scholar]

- Joranson DE, Maurer MA. Improving State Medical Board Policies: Influence of a Model. Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics. 2003;31:119–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2003.tb00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskie B, Knight BG, Liebig PS. State Legislation Concerning Individuals with Dementia: An Evaluation of Three Theoretical Models of Policy Formation. Gerontologist. 2001;41:383–393. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman S, Shim J, Russ A. Old Age, Life Extension, and the Character of Medical Choice. Journals of Gerontology B. 2006;61:S175–S184. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.4.s175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khator R. Recycling: A Policy Dilemma for American States? Policy Studies Journal. 1993;21:210–226. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. 2nd ed. New York: Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lammers W, Klingman D. State Policies and Aging: Sources, Trends, and Options. Toronto: Lexington Books; 1984. [Google Scholar]