Abstract

Prompt gamma rays emitted from biological tissues during proton irradiation carry dosimetric and spectroscopic information that can assist with treatment verification and provide an indication of the biological response of the irradiated tissues. Compton cameras are capable of determining the origin and energy of gamma rays. However, prompt gamma monitoring during proton therapy requires new Compton camera designs that perform well at the high gamma energies produced when tissues are bombarded with therapeutic protons. In this study we optimize the materials and geometry of a three-stage Compton camera for prompt gamma detection and calculate the theoretical efficiency of such a detector. The materials evaluated in this study include germanium, bismuth germanate (BGO), NaI, xenon, silicon and lanthanum bromide (LaBr3). For each material, the dimensions of each detector stage were optimized to produce the maximum number of relevant interactions. These results were used to predict the efficiency of various multi-material cameras. The theoretical detection efficiencies of the most promising multi-material cameras were then calculated for the photons emitted from a tissue-equivalent phantom irradiated by therapeutic proton beams ranging from 50 to 250 MeV. The optimized detector stages had a lateral extent of 10 × 10 cm2 with the thickness of the initial two stages dependent on the detector material. The thickness of the third stage was fixed at 10 cm regardless of material. The most efficient single-material cameras were composed of germanium (3 cm) and BGO (2.5 cm). These cameras exhibited efficiencies of 1.15 × 10−4 and 9.58 × 10−5 per incident proton, respectively. The most efficient multi-material camera design consisted of two initial stages of germanium (3 cm) and a final stage of BGO, resulting in a theoretical efficiency of 1.26 × 10−4 per incident proton.

1. Introduction

The fundamental advantages of proton radiation therapy compared to x-ray therapy are the finite range of the proton beam and the concentration of dose in the Bragg peak at the end of the beam range. This finite range can benefit patients by decreasing the dose distal to the target. However, the steep distal dose falloff must be accurately located to ensure adequate target coverage and avoidance of critical structures. Routine patient-specific quality assurance procedures are used to verify the proper function of the proton accelerator and delivery systems, but due to the high sensitivity of the beam range to density inhomogeneities and the effects of setup errors and motion, it is desirable to have a method of in vivo measurement as a means of verifying beam range and determining the actual distribution of delivered dose. One proposed method is to measure secondary gamma radiation emitted from the treated tissue as a dose indicator (Bennett et al 1978, Polf et al 2009a).

Some nuclei bombarded by a therapeutic proton beam will be excited into a heightened energy state. A nucleus excited in this manner will rapidly de-excite, emitting a characteristic gamma ray, a process known as ‘prompt emission’ (Sutcliffe et al 1991). Recent efforts have shown that prompt emission is strongly correlated with the distribution of proton dose, suggesting that it could be used for in vivo proton dose verification (Min et al 2009, Testa et al 2009, Polf et al 2009b).

Based on these preliminary results, many researchers have begun to investigate methods of in vivo imaging of dose deposition through the measurement of ‘prompt emission’ gamma rays (Min et al 2009, Frandes et al 2010, Testa et al 2009, Polf et al 2009b). Many of these studies have focused on methods of measuring the spatial distribution of the prompt emission from the patient during irradiation using a Compton camera.

Compton cameras are multi-stage detectors which use the kinematics of Compton scattering as a means of measuring energy and directional information about incident gamma rays. Compton cameras have been used for imaging in both nuclear medicine (Solomon and Ott 1988) and in astrophysics (Phillips 1995). However, due to the high energy (up to 15MeV) and poly-energetic nature of the prompt gamma spectrum produced during proton therapy, traditional Compton cameras designed for nuclear medicine show low intrinsic efficiency and are less effective for application to proton therapy. One recent report concluded that a Compton camera composed of detection components typically used in nuclear medicine cameras provided much too low of an intrinsic efficiency to allow for its use as an in vivo imaging tool during charged particle therapy (Richard et al 2009). Therefore, we believe that to make the Compton camera a usable in vivo dose verification technology for proton radiotherapy, it must be specifically redesigned to optimize its ability to measure the spectrum of prompt gamma rays emitted from tissues during proton irradiation.

Recently, Peterson et al (2010) carried out a Monte Carlo study of a three-stage Compton camera to optimize design parameters for the measurement of prompt gamma rays emitted during proton beam radiotherapy. In that study, the authors optimized a Compton camera composed of three high-purity germanium detection stages. The optimal design was then tested for its feasibility as a patient dose verification device. They determined that with the proper design, it was theoretically feasible to measure a sufficient prompt gamma ray signal to allow for in vivo measurement of the proton beam range. While their system provided a theoretical basis for use of the three-stage Compton camera, their study was limited to a single detector material. We believe that a Compton camera constructed of other materials commonly used for gamma ray detection may provide a higher overall detection efficiency or a more practical camera design.

The purpose of this study is to identify the most suitable detector materials for a three-stage Compton camera employed in proton therapy dose verification. Monte Carlo and analytical calculations are employed to compare Compton camera detection efficiencies for single-material and multi-material detectors. An appropriate choice of detector materials may lead to an improvement in the overall prompt gamma detection efficiency that is achievable for a three-stage Compton camera.

2. Materials and methods

In this section we give a brief overview of our techniques, including important details of the Monte Carlo model and the equations used to calculate gamma ray detection efficiency for the materials studied in this work. For a detailed explanation and derivation of these methods and equations, the reader is referred to Peterson et al (2010).

2.1. Monte Carlo model

The calculations in this study were performed using the Monte Carlo toolkit Geant4 version 9.1 (Agostinelli et al 2003). Of particular interest are gamma ray interactions in the modeled Compton camera, as well as proton beam interactions in tissue, including proton–electron and proton–nuclear interactions. Electromagnetic interactions were calculated using the standard and low-energy Geant4 electromagnetic models. Elastic and inelastic scattering between hadrons and nucleons was calculated using the G4Elastic model, the ‘pre-compound’ model, and the low-energy inelastic model. A maximum step size of 1 m was enforced for all particle tracking. Particles tracked included protons, neutrons, photons, and all other secondary particles with ranges greater than 1 mm. The tracking of particles with less than 1 mm range was stopped, and all remaining energy was deposited locally. For further detail about the calculation models, particle transport, and energy cuts used in the model, the reader is referred to previously published studies (Polf et al 2009b, Peterson et al 2009).

The modeled three-stage Compton camera consisted of three square detector stages aligned parallel to one another with their centers sharing a common axis and separated by a fixed distance of 5 cm. The front face of the first detector stage was placed at a fixed distance of 15 cm from the isocenter. Detector stage spacing and phantom–detector spacing were investigated in a previous publication, in which it was reported that a decrease in the spacing led to increased detection efficiency (Peterson et al 2010). Since this is a geometrical effect and not related to the properties of the materials studied, we did not study effects of detector spacing in this work. Six promising detector materials were selected for this study, including germanium (Ge), bismuth germanate (Bi4Ge3O12, abbreviated BGO), sodium iodide (NaI), xenon (Xe), lanthanum bromide (LaBr3), and silicon (Si).

The events recorded in the detectors included: (1) the total number of prompt gammas entering each detector stage, (2) the total number of gamma interactions within each detector stage, (3) ‘single-scatters’ in which a gamma Compton scatters once (and only once) in the first detector stage, (4) so-called double-scatters in which a gamma Compton scatters once in the first stage and once in the second stage, and (5) ‘triple-scatters’ in which a gamma undergoes a double scatter and then any Compton scatter, photoelectric, or pair production interaction in the third detector stage. All output data files consisted of ROOT (Brun and Rademakers 1997) histograms. For each calculation, between 107 and 109 source particle histories were simulated in order to ensure a 1 sigma standard deviation of less than 5% for all values within the data histograms.

Detection efficiency studies for each detector stage were carried out using an isotropic point source of gamma rays with energies corresponding to the most prominent prompt gamma emission lines from tissues: the 2.33 MeV, 4.44 MeV and 6.13 MeV characteristic prompt gammas from nitrogen, carbon and oxygen, respectively (Polf et al 2009a). After optimizing each detector stage using the characteristic prompt gamma energies, the spectral response of each optimized stage was fully characterized by running calculations for gammas ranging from 0 to 10 MeV in 0.5 MeV increments.

The detection efficiency of the optimized detectors was calculated by replacing the gamma point source with a proton pencil beam incident on a homogeneous block of tissue. The tissue composition was defined according to the ICRU Report 44 definition of adult average soft tissue (ICRU 2007). Mono-energetic proton beams with energies in the clinically useful range from 50 to 250 MeV were included in the calculations. A model of the proton nozzle was not included in this study. However, a previous study incorporating the proton nozzle indicated that prompt gamma emission from interactions in the nozzle accounted for 1–7% of the total prompt gamma fluence near the patient (Peterson and Polf 2009). That study recommended that a Compton camera be shielded from gammas produced in the nozzle to avoid contamination of the prompt gamma signal from the patient. This study assumes that appropriate shielding or signal discrimination is employed so that the signals due to secondary gammas and neutrons from the nozzle can be neglected.

2.2. Detector efficiency

The overall efficiency of the three-stage Compton camera is modeled as a function of the gamma interaction efficiency and transportation efficiency of each detector stage (Peterson et al 2010). The interaction efficiency of detector stage m, denoted as , is defined as the number of interactions of interest within stage m divided by the number of gamma rays entering that stage. The transportation efficiency between stages m and n, denoted as , is defined as the number of gamma rays interacting in stage m which subsequently propagate to stage n. Therefore the overall detection efficiency of a three-stage Compton camera is defined as the product of the interaction efficiencies of each detector stage and the transportation efficiencies between each stage of the detector as given by the equation

| (1) |

where is the efficiency of triple-scatter detection for the camera with the gamma point source, is the transportation efficiency from the point source to the first detector stage, is the interaction efficiency of detector material a for stage 1, is the transportation efficiency between detector stages 1 and 2, and represent the interaction efficiency of stage 2 composed of material b and the transportation efficiency between stages 2 and 3. represents the interaction efficiency of stage 3 composed of material c. In a previous publication (Peterson et al 2010), it was shown that equation (1) can be written as , where Nprompt is the number of prompt gammas emitted from the isotropic source during irradiation, and Its3 is the number of prompt gammas that triple-scatter in the Compton camera.

Using equation (1), it is possible to optimize a camera made of a single material (with a, b, and c defined as the same material) or multiple materials with a, b, and c defined as different materials. For the calculations with a proton beam irradiating a tissue phantom, the overall efficiency of detecting secondary prompt gammas per incident proton, , is given by the equation

| (2) |

where Nproton is the number of protons incident on the tissue phantom during irradiation.

2.3. Optimization

2.3.1. Single-material optimization

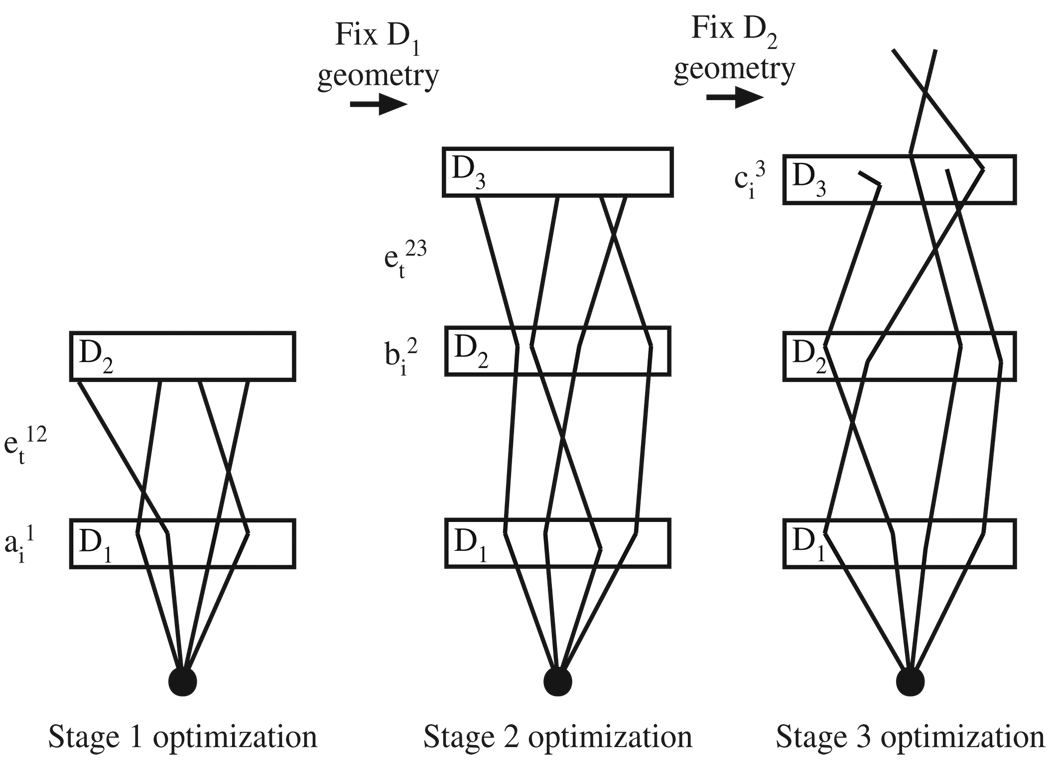

Optimization of a three-stage single-material Compton camera was focused on determining the most efficient detection geometry for each material studied. This was accomplished using a three-step process to maximize prompt gamma detection efficiency as a function of width and thickness in each stage separately, as illustrated in figure 1. Starting with the first detector stage, the efficiency of gamma ‘single-scatter’ events per entering prompt gamma and the transportation efficiency between the first and second stages were optimized for each of the six materials. The width and thickness were then fixed, and the optimization proceeded to the second stage. For the second stage, the maximum efficiency of ‘double-scatter’ events per ‘single-scattered’ gamma that entered stage two was determined as a function of thickness and width for each material studied. Similarly, with the dimensions of stages 1 and 2 fixed at their optimal values, efficiency of ‘triple-scatter’ events occurring in the third detector stage was optimized as a function of width and thickness.

Figure 1.

Overview of the optimization process. First the parameters ai1 and et12 were optimized by adjusting the dimensions of D1. Next, the optimized D1 dimensions were fixed, and the parameters and et23 were optimized by adjusting the dimensions of D2. Finally, the optimized D2 dimensions were fixed and the parameter ci3 was optimized by adjusting the dimensions of D3.

Efficiencies were calculated for each stage at lateral widths of 10, 25, 50, and 100 cm. After optimization of the width, the efficiencies were calculated for thicknesses of 1–12 cm at 1 cm intervals to determine the optimal efficiency as a function of thickness. Because of its high density, the peak detection efficiency of BGO occurs at a smaller thickness than the other materials. For this reason, BGO efficiencies were calculated for thicknesses of 1–6 cm at 0.5 cm intervals. As the thickness was varied, the same 5 cm separation between detector stages was maintained, resulting in a changing total camera length.

For a given width, the optimal thickness of each detector stage was selected by taking the maximum of the product of the interaction efficiency and the transportation efficiency between that stage and the following stage. In this way the optimal detector thickness for the first two stages is that which results in the greatest number of ‘single-scattered’ and ‘double-scattered’ gammas entering the subsequent detector stage. Because a three-stage Compton camera only requires position information from its third stage, any interaction will suffice for event detection, including Compton scatter, photoelectric interaction and pair production. Therefore, the optimal detector thickness for the third detector stage was the thickness resulting in the greatest number of gamma interactions.

2.3.2. Multi-material optimization

Following the optimization of single-material detectors, the optimization was broadened to allow each detector stage to be made of any one of the six materials studied. For these calculations, a fixed width was used for all three detector stages. This removed the geometric dependence of the detection efficiency, allowing us to focus the optimization solely on material. Estimates of the overall detector efficiency were calculated by multiplying together the interaction efficiencies and transportation efficiencies already calculated during the single-material optimization, according to equation (1). Since it was impractical to perform Monte Carlo calculations on all 216 detector material permutations, this analytical calculation method was employed to identify the most efficient multi-material configurations.

The detection efficiency was calculated for each of the 216 detector permutations that are possible for a three-stage Compton camera with six possible materials for each stage. The detectors were ranked according to their overall efficiency, which was determined by calculating the area under the efficiency versus energy curve for each material combination. This ranking procedure identified the most promising multi-material detector configurations. The accuracy of this analytical ranking procedure was then verified by comparing the estimated detector efficiency to complete Monte Carlo calculations of efficiency for the three most efficient detector configurations.

Upon completion of the multi-material optimization with the isotropic gamma source, we calculated the theoretical response of the most efficient configurations for detecting prompt gamma rays emitted during proton beam radiotherapy. For these calculations, we replaced the isotropic gamma source with a proton beam irradiating a tissue phantom. Calculations of prompt gamma detection efficiency were then performed over a range of proton energies commonly used in a clinical setting (50–250 MeV).

3. Results

The optimal width and thickness values determined for each stage were not significantly different for the three characteristic gamma energies studied. Any differences were less than the thickness and width increments used in our calculations. This finding is in agreement with the results of Peterson et al (2010). Therefore, the figures presented in this paper show only the results of calculations with 4.44 MeV incident gamma rays in order to preserve readability.

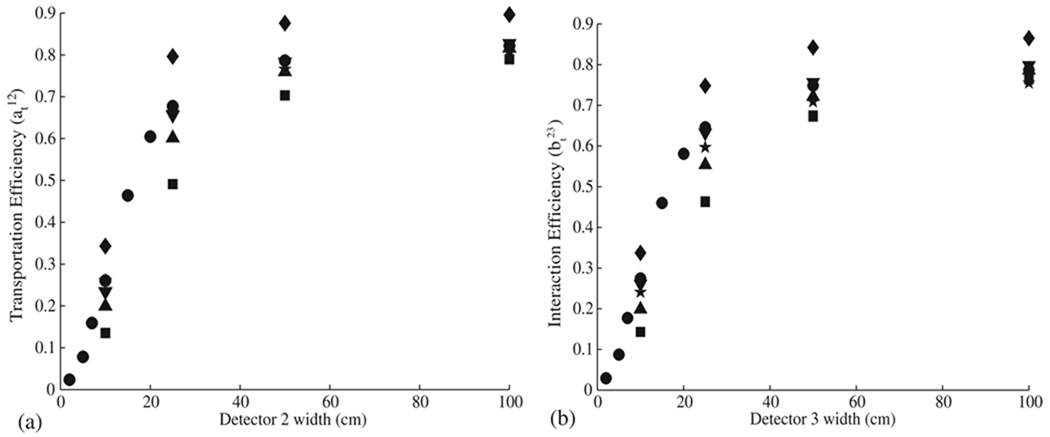

3.1. Width

The width of each detector directly affects the transportation efficiency by determining the solid angle covered by the detector surface. Figure 2 shows that the transportation efficiencies for each material increase with detector width, asymptotically approaching maximum efficiency values ranging from 75% for Xe and Si to 90% for BGO. The absolute maximum transportation efficiency is obtained with an infinitely wide detector. Of course, a number of engineering realities limit the physical width of detectors which can currently be manufactured and assembled. This requires us to instead select a width value for each detector stage that is currently commercially available for each detector material studied. To meet this ‘commercial availability’ requirement, a width of 10 cm was selected as a practical size for all detector stages for all materials. We note that it would be possible to build detector stages of larger widths by combining multiple detectors of this size, thus increasing the overall transportation efficiency between detector stages and ultimately the detection efficiency of the camera.

Figure 2.

The transportation efficiency between (a) the first and second detector stages and the (b) second and third detector stages is plotted as a function of the detector stage width for Ge (●), BGO (♦), NaI (▲), Xe (■), Si (☆), and LaBr3 (▼).

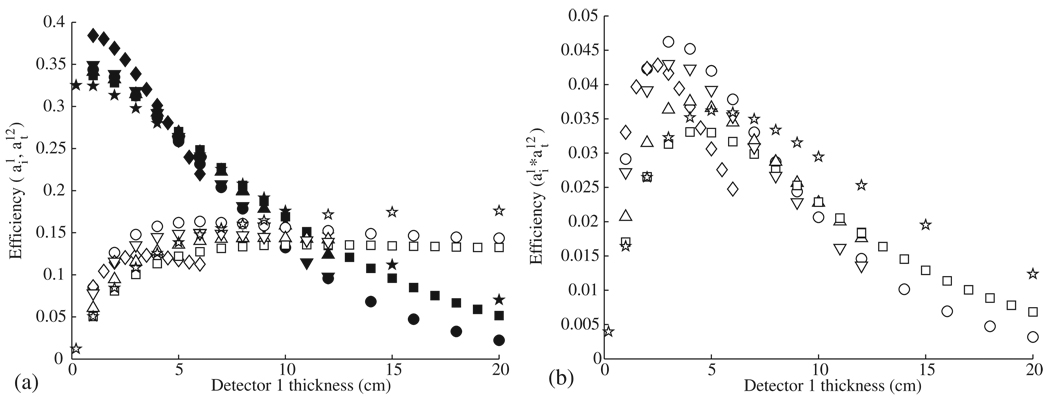

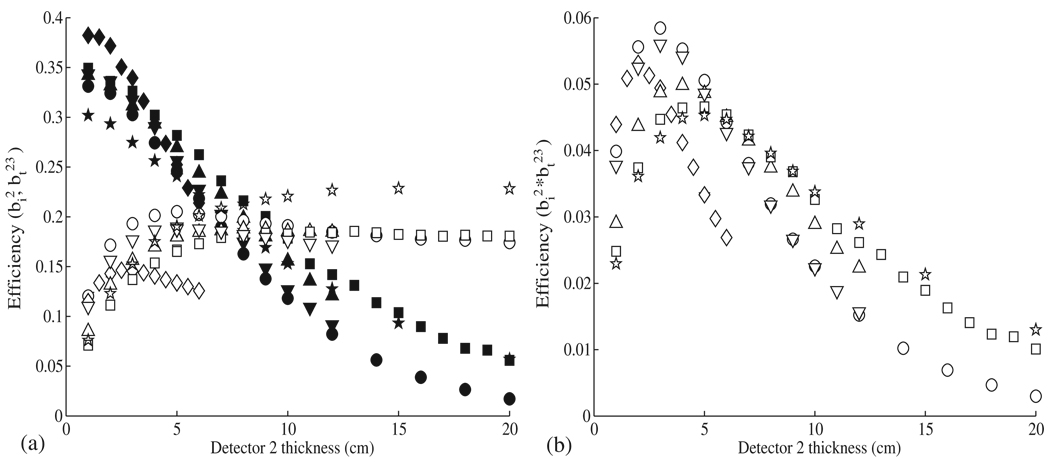

3.2. Thickness

The thickness of the detector stages affects both the interaction efficiency and the transportation efficiency, with the overall efficiency as a function of thickness being defined as the product of the interaction efficiency and the transportation efficiency. These parameters are plotted for the first detector stage in figure 3 and for the second stage in figure 4.

Figure 3.

(a) The interaction efficiency for the first detector (open symbols) and the transportation efficiency between the first and second detectors (solid symbols) is shown for each material studied as a function of thickness for Ge (○), BGO (◊), NaI (△), Xe (□), Si (☆), and LaBr3 (▽). (b) The overall efficiency for the first detector is determined by multiplying the interaction efficiency and transportation efficiency .

Figure 4.

(a) The interaction efficiency for the second detector (open symbols) and the transportation efficiency (bt23) between the second and third detectors (closed symbols) is shown as a function of thickness for Ge (○), BGO (◊), NaI (△), Xe (□), Si (☆), and LaBr3 (▽). (b) The overall efficiency for the second detector is determined by multiplying the interaction efficiency and transportation efficiency .

For the first and second detector stages, germanium showed the highest overall efficiency, followed in order by BGO, LaBr3, NaI, xenon and silicon. While all other materials showed a similar interaction efficiency spectral response, BGO showed a lower interaction efficiency and a smaller optimal thickness than the other materials. The decrease in optimal thickness is expected because of the relatively high density of BGO (7.13 g cm−3 compared to 5.32 g cm−3 for Ge). The decrease in the BGO interaction efficiency is likely a result of the high-Z value of bismuth, resulting in an increase in the pair production cross-section for BGO. The corresponding decrease in the number of Compton scatter interactions results in a lower interaction efficiency.

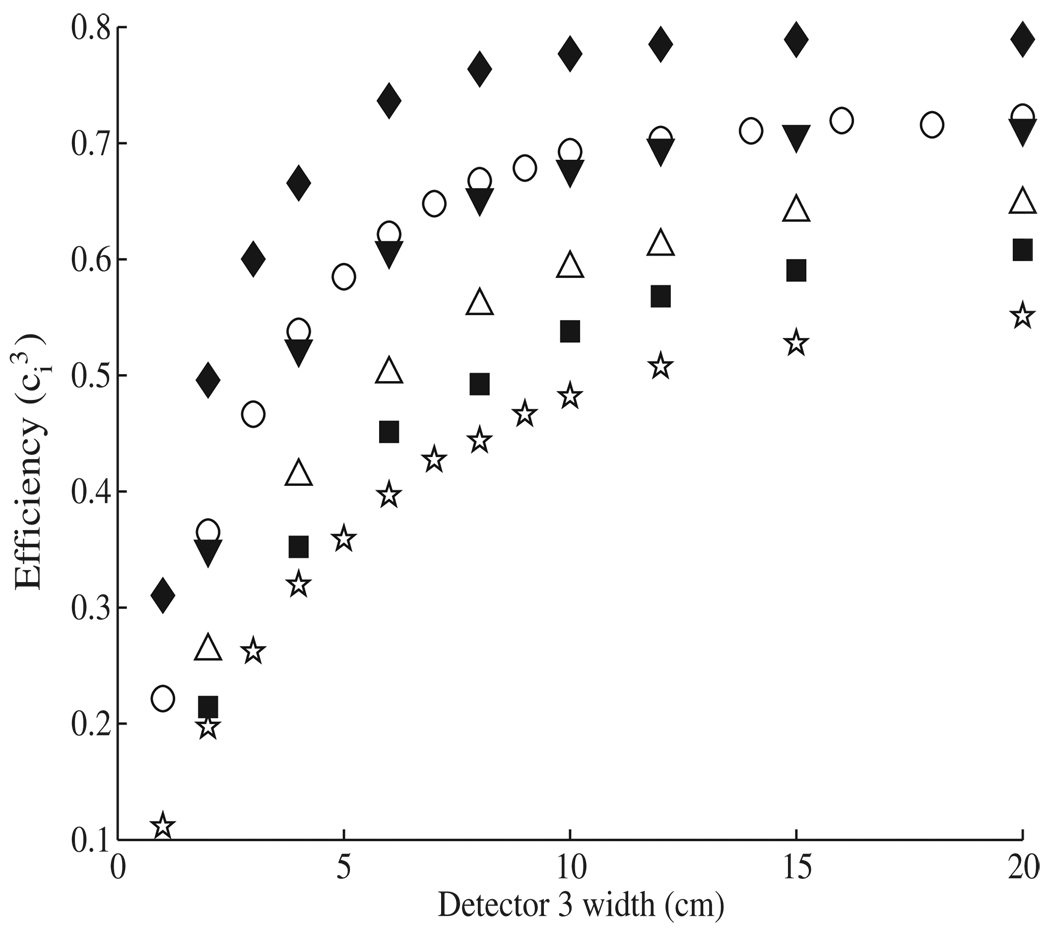

Because the third detector stage in our design is the final stage, only the interaction efficiency is considered during optimization, and all photon interactions (Compton scattering, photo-electric absorption and pair production) are counted. Figure 5 shows that for all materials studied, the interaction efficiency of the third stage rose steeply with thickness for the first 5–7 cm, after which the slope decreased toward a material-specific maximum. At a thickness of 10 cm, most materials have reached or are very near their maximum values; therefore, 10 cm was selected as the optimum third stage thickness for all materials. BGO showed the highest efficiency in the optimization of the third detector, with an interaction efficiency of 77.7% at 10 cm thickness, followed by Ge, LaBr3, NaI, xenon and silicon with interaction efficiencies ranging from 69.3% to 48.2% for a thickness of 10 cm.

Figure 5.

The interaction efficiency is plotted versus the detector thickness for the third detector for Ge (○), BGO (♦), NaI (△), Xe (■), Si (☆), and LaBr3 (▼). Interaction efficiency in this case includes all interactions, not just single Compton scatters.

3.3. Camera optimization

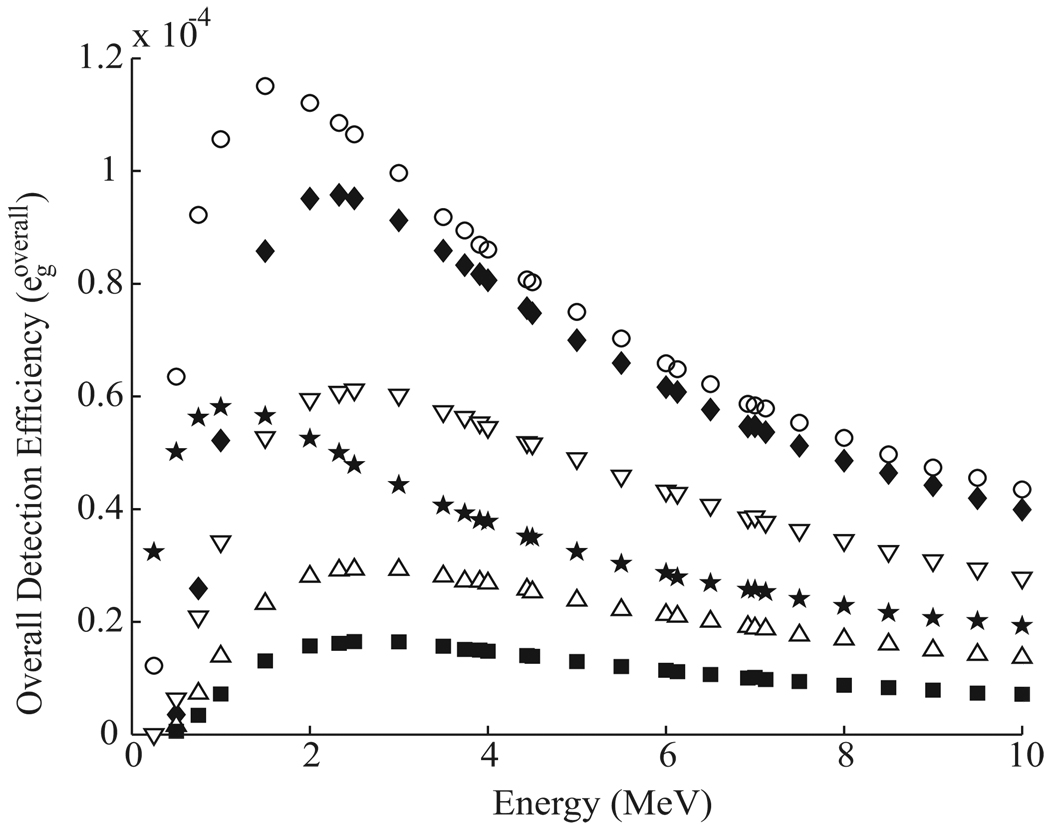

The prompt gamma detection efficiencies of optimized single-material Compton cameras were calculated as a function of gamma ray energy for each material studied. The overall detection efficiency for each single-material camera is graphed as a function of energy in figure 6. The germanium detector showed the highest overall efficiency, followed by BGO, LaBr3, silicon, NaI and xenon.

Figure 6.

The overall detection efficiency (egoverall) of each optimized single-material Compton camera as a function of energy for Ge (○), BGO (♦), NaI (△), Xe (■), LaBr3 (▽), and Si (★).

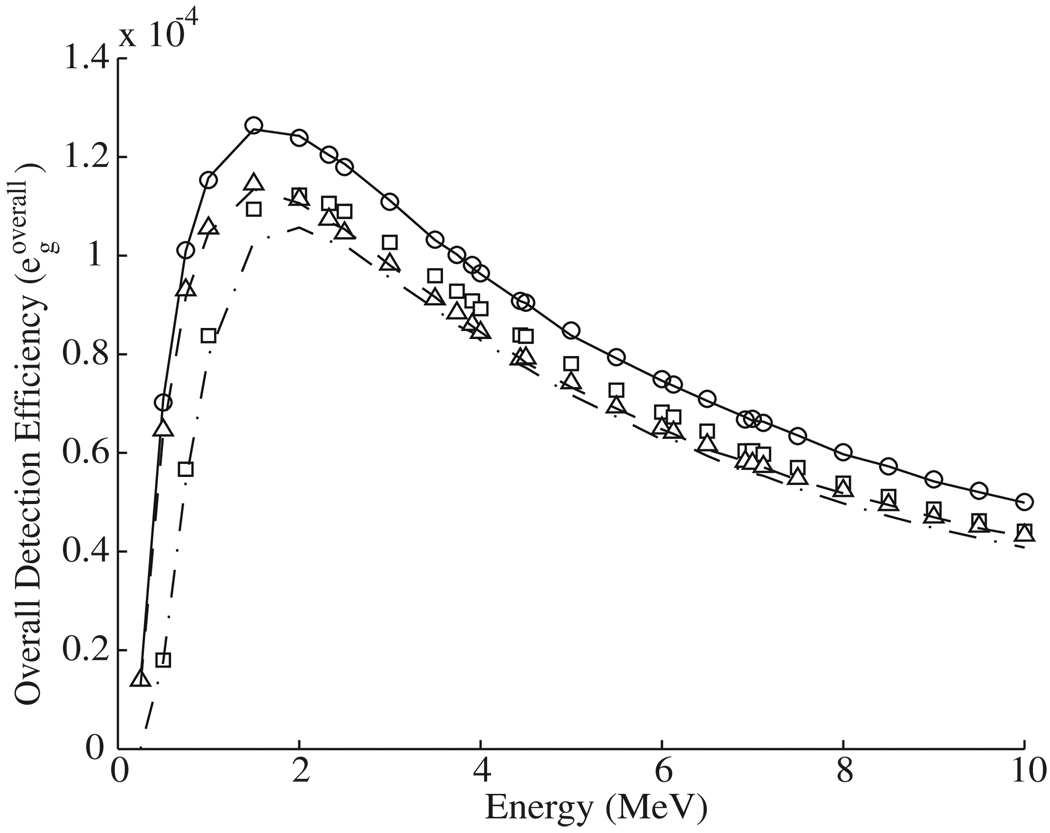

The analytical multi-material detection efficiency calculation method was validated by performing direct Monte Carlo simulations of the three most efficient multi-material camera configurations. The results of the analytical and Monte Carlo calculations are shown in figure 7. The resulting Monte Carlo-calculated efficiency curves showed good agreement with those calculated using equation (1). The configurations and properties of the optimized single-material and multi-material Compton cameras are given in table 1.

Figure 7.

The energy dependence of the overall detection efficiency (egoverall) of the three most efficient composite detectors. The symbols represent the results of efficiency calculations using equation (1) for Ge–Ge–BGO (○), BGO–Ge–BGO (□), Ge–Ge–LaBr3 (△). The lines show the results of separate Monte Carlo calculations based on the optimized geometry and materials. The solid line is for Ge–Ge–BGO, the dash-dotted line is for BGO–Ge–BGO, and the dashed line is for Ge–Ge–LaBr3.

Table 1.

Optimized detector configurations for each single-material Compton camera and for the three most efficient multi-material cameras. For each camera the peak efficiency is listed and the energy at which the peak efficiency is reached. All detectors have a width of 10 cm.

| Detector 1 | Detector 2 | Detector 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | Thickness (cm) |

Material | Thickness (cm) |

Material | Thickness (cm) |

Peak efficiency |

Energy (MeV) |

| Single-material | |||||||

| Germanium | 3 | - | 3 | - | 10 | 1.15 × 10−4 | 1.5 |

| BGO | 2.5 | - | 2.5 | - | 10 | 9.58 × 10−5 | 2.33 |

| NaI | 4 | - | 4 | - | 10 | 2.93 × 10−5 | 2.5 |

| Xenon | 4 | - | 4 | - | 10 | 1.65 × 10−5 | 2.5 |

| LaBr3 | 3 | - | 3 | - | 10 | 6.12 × 10−5 | 2.5 |

| Silicon | 5 | - | 5 | - | 10 | 5.81 × 10−5 | 1 |

| Multi-material | |||||||

| Germanium | 3 | Germanium | 3 | BGO | 10 | 1.26 × 10−4 | 1.5 |

| BGO | 2.5 | Germanium | 3 | BGO | 10 | 1.12 × 10−4 | 2 |

| Germanium | 3 | Germanium | 3 | LaBr | 10 | 1.14 × 10−4 | 1.5 |

3.4. Prompt gamma detection efficiency during proton irradiation

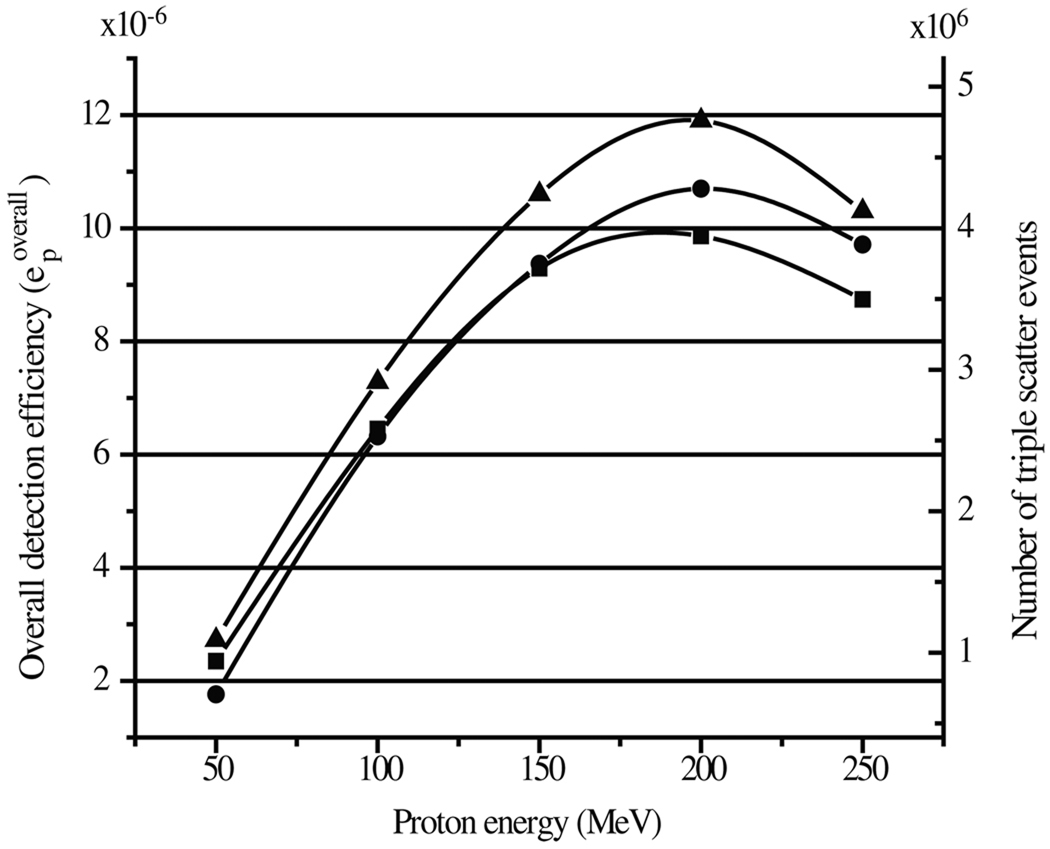

The efficiency of detecting characteristic prompt gamma rays emitted from tissue during proton irradiation was calculated for each of the three optimized multi-material detectors. The isotropic gamma source was replaced with a tissue-equivalent phantom and irradiated with proton beams with energies ranging from 50 to 250 MeV. The detection efficiencies for prompt gammas emitted during proton irradiation are shown in figure 8 for the three most efficient multi-material cameras. The Ge–Ge–BGO detector showed the highest response, with an overall efficiency of 1.2 ± 10−5 per incident proton.

Figure 8.

The left axis indicates the overall detection efficiency per incident proton (epoverall) for prompt gammas emitted during proton irradiation of a tissue phantom. The responses of three multi-material detectors are shown: germanium–germanium–BGO (▲), BGO–germanium–BGO (■), and germanium–germanium–LaBr3 (●). The right axis indicates the total number of triple-scatter events expected from a treatment delivery of 4 × 1011 protons.

A single proton ‘spot’ delivered with the PTCH spot scanning nozzle consists of ~6 × 107 protons. Many of the spots are ‘repainted’ or delivered up to 10 times per treatment field, resulting in ~6 × 108 protons being delivered per spot for the highest weighted (most distal) spots. For an entire daily treatment we expect on the order of 4 × 1011 protons to reach the patient (Smith et al 2009). This would result in ~1000 triple scatter events per spot and approximately 6 × 106 triple-scatter events in a single daily treatment if measured with an optimized Ge–Ge–BGO Compton camera. This suggests that the multi-material three-stage Compton cameras in this study could be used for imaging the entire treatment field, but not necessarily individual spots in proton beam scanning delivery.

4. Discussion and conclusions

We have studied the feasibility of using a multi-material three-stage Compton camera to detect prompt gamma rays emitted from biological tissues during proton radiation therapy. The geometry of single-material cameras for six different materials was optimized for the detection of a ‘triple-scatter’ interaction in the Compton camera which allows for localization of the origin of the gamma ray emission within the patient. A single-material germanium detector showed the highest single-material efficiency, followed by BGO, which showed a 17% decrease. Despite the lower efficiency for BGO, other aspects such as increased spatial or energy resolution, room temperature operation, and lower cost may make BGO a viable option for a Compton camera design.

We determined that a three-stage Compton camera consisting of multiple materials can provide superior overall detection efficiency compared to a single-material detector. This improvement stems from the different role of the first two detector stages as compared to the final stage. The first two stages are designed to detect a single Compton scatter interaction in each stage, while the third stage is designed to detect as many interactions as possible of any type (Compton scattering, photo-electric absorption and pair production). Specifically, we calculated that a camera with its first two stages made of high-purity germanium and its final stage of BGO can obtain a maximum overall detection efficiency of approximately 1.26 × 10−4, while a germanium-only detector yields an approximate efficiency of 1.15 × 10−4, an increase of nearly 10%.

Other material combinations were found which achieved essentially the same detection efficiency as a germanium-only detector, including BGO–Ge–BGO and Ge–Ge–LaBr3. The most efficient detector not containing a germanium stage was composed entirely of BGO, which had a peak efficiency 17% below the germanium-only camera and 24% below the Ge–Ge–BGO camera. This suggests that several different materials could be used in constructing a Compton camera for this application, allowing other factors such as cost and convenience to influence material selection

In calculating the number of triple scatter events in a Compton camera, it is important to consider the other events occurring in the detector that do not contribute to useful signal. Our calculations indicate that approximately 0.15% of gammas entering the Compton camera will result in valid triple-scatter events. In order to identify the few triple-scatter events and filter out the non-useful events, fast event timing and post-processing with the Compton scattering formula must be employed.

Neutrons generated in the proton nozzle and the patient will generate additional spurious signals in a Compton camera. As the purpose of this study was to evaluate prompt gamma detection efficiency, neutron interactions in the detector were not recorded. However, previous studies have indicated that the neutron fluence near the isocenter may be comparable to the number of triple-scatters detected in a given passive scattering treatment (Yan et al 2002, NCRP 1971), while scanned beam treatments exhibit lower neutron fluences by an order of magnitude (Clasie et al 2010, Schneider et al 2002). Accordingly, the detector materials used in proton therapy Compton cameras should have a low neutron interaction cross-section and should be capable of discriminating between signals from neutrons and gammas.

Considering the low number of triple scatters per spot and the high background, it may be difficult to measure individual scanned proton beams in real time using current electronics and Compton camera technology. To extend this concept to imaging of individual spots delivered during scanned beam treatments, continued development of Compton camera technology is needed. However, we expect that the Compton camera design in this study could be used effectively as an integrating detector to verify the location of the high-dose region in passive scattering or spot scanning treatments.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by Award Number R21CA137362 from the National Cancer Institute.

References

- Agostinelli S, et al. GEANT4—a simulation toolkit. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. 2003;506:250–303. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GW, Archambeau JO, Archambeau BE, Meltzer JI, Wingate CL. Visualization and transport of positron emission from proton activation in vivo. Science. 1978;200:1151–1153. doi: 10.1126/science.200.4346.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun R, Rademakers F. ROOT—an object oriented data analysis framework. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. 1997;389:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Clasie B, Wroe A, Kooy H, Depauw N, Flanz J, Paganetti H, Rosenfeld A. Assessment of out-of-field absorbed dose and equivalent dose in proton fields. Med. Phys. 2010;37:311–321. doi: 10.1118/1.3271390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frandes M, Zoglauer A, Maxim V, Prost R. A tracking Compton-scattering imaging system for hadron therapy monitoring. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2010;57:144–150. [Google Scholar]

- International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements (ICRU) ICRU Report No. 44. Bethesda, MD: ICRU; 2007. Tissue substitutes in radiation dosimetry and measurement. [Google Scholar]

- Min CH, Park JG, Kim CH. Preliminary study for determination of distal dose edge by measuring 90 deg prompt gammas with an array-type prompt gamma detection system. Nucl. Technol. 2009;168:89–92. [Google Scholar]

- National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements (NCRP) NCRP Report No. 38. Bethesda, MD: NCRP; 1971. Protection against neutron radiation. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson S, Polf J. Characterizing secondary gamma fluence from a scanned beam proton therapy nozzle. Med. Phys. 2009;36:2613. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson S, Polf J, Ciangaru G, Frank SJ, Bues M, Smith A. Variations in proton scanned beam dose delivery due to uncertainties in magnetic beam steering. Med. Phys. 2009;36:3693–3702. doi: 10.1118/1.3175796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson S, Robertson D, Polf J. Optimizing a three-stage Compton camera for measuring prompt gamma rays emitted during proton radiotherapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 2010;55:6841. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/22/015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips GW. Gamma-ray imaging with Compton cameras. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B. 1995;99:674–677. [Google Scholar]

- Polf JC, Peterson S, Ciangaru G, Gillin M, Beddar S. Prompt gamma-ray emission from biological tissues during proton irradiation: a preliminary study. Phys. Med. Biol. 2009a;54:731–743. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/3/017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polf JC, Peterson S, McCleskey M, Roeder BT, Spiridon A, Beddar S, Trache L. Measurement and calculation of characteristic prompt gamma ray spectra emitted during proton irradiation. Phys. Med. Biol. 2009b;54:N519–N527. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/22/N02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard MH, et al. Design study of a Compton camera for prompt gamma imaging during ion beam therapy; Nuclear Science Symp. Conf. Record (NSS/MIC), IEEE 2009; 2009. pp. 4172–4175. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider U, Agosteo S, Pedroni E, Besserer J. Secondary neutron dose during proton therapy using spot scanning. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2002;53:244–251. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02826-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, et al. The MD Anderson proton therapy system. Med. Phys. 2009;36:4068–4083. doi: 10.1118/1.3187229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon CJ, Ott RJ. Gamma-ray imaging with silicon detectors—a Compton camera for radionuclide imaging in medicine. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. 1988;273:787–792. [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe JF, Waker AJ, Smith AH, Barker MCJ, Smith MA. A feasibility study for the simultaneous measurement of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen using pulsed 14.4 Mev neutrons. Phys. Med. Biol. 1991;36:87–98. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/36/5/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa E, et al. Dose profile monitoring with carbon ions by means of prompt-gamma measurements. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B. 2009;267:993–996. [Google Scholar]

- Yan X, Titt U, Koehler AM, Newhauser WD. Measurement of neutron dose equivalent to proton therapy patients outside of the proton radiation field. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A. 2002;476:429–434. [Google Scholar]