Abstract

Preeclampsia is a major cause of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality worldwide, however, its etiology remains unclear. Abnormal placental angiogenesis during pregnancy resulting from high levels of anti-angiogenic factors, soluble Flt1 (sFlt1) and soluble endoglin (sEng), has been implicated in preeclampsia pathogenesis. Accumulating evidence also points to a role for these anti-angiogenic proteins as serum biomarkers for the clinical diagnosis and prediction of preeclampsia. Uncovering the mechanisms of altered angiogenic factors in preeclampsia may also provide insights into novel preventive and therapeutic options.

Introduction

Preeclampsia, a pregnancy-related disorder characterized by hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation, affects 5% of pregnancies and is a major cause of maternal and fetal mortality.1 Delivery of the placenta has been shown to resolve the acute clinical symptoms of preeclampsia, suggesting that the placenta plays a central role in preeclampsia pathogenesis.2 During normal pregnancy, the placenta undergoes dramatic vascularization to enable circulation between the fetus and the mother. Placental vascularization involves vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and pseudovasculogenesis or maternal spiral artery remodeling. These processes require a delicate balance of pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors. In preeclamptic pregnancies, several anti-angiogenic factors, such as soluble Flt1 (sFlt1) and soluble endoglin (sEng), are produced by the placenta in higher than normal quantities.3 The imbalance of pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors in preeclampsia is thought to trigger abnormal placental vascularization and disease onset. Underlying genetic explanations for the overproduction of anti-angiogenic factors in preeclampsia are still being proposed. This review will focus on normal vascular development in the placenta, the angiogenic imbalance that occurs during preeclampsia, and the role of genetics in preeclamptic pregnancies.

Placental Vascular Development

The development of the placental vascular network involves vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and pseudovasculogenesis or maternal spiral artery remodeling. Vasculogenesis, the differentiation of endothelial precursors into endothelial cells lining the vascular system, begins in the first few weeks of a normal pregnancy. During vasculogenesis, a subpopulation of mesenchymal precursor cells transforms into hemiangioblastic endothelial precursors.4 Differentiation of these cells results in the generation of new blood vessels in the placenta.4

Vasculogenesis is followed by angiogenesis, the formation of new capillaries from preexisting ones.5 Starting at day 21 of pregnancy, soluble angiogenic factors, expressed in the trophoblasts of the placenta, maternal decidua, and macrophages mediate capillary formation in the chorionic villi of the placenta.5 The capillary beds of the villi expand continuously until week 26 of gestation. From week 26 until term, villous vascular growth is primarily limited to non-branching angiogenesis due to the formation of mature intermediate villi that contain poorly branched capillary loops.4 Among the angiogenic factors expressed by the placenta during this phase, VEGF and PlGF play a central role. The vascular endothelial growth factor family includes VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, and VEGF-D.6 VEGF-A, an endothelial specific mitogen, is expressed in three different isoforms (121, 165, and 189).7 VEGF-A induces placental vascular development through its interactions with high affinity receptor tyrosine kinases Flt1 and KDR on placental endothelial cells.8 VEGF has been shown to be involved in the regulation of endothelial cell stability, ependymal cell function, and periventricular permeability.9 Inactivation of VEGF results in embryonic lethality and significant defects in placental vasculature.10 In addition to VEGF, placental growth factor is another key pro-angiogenic factor produced by the placenta. PlGF is also expressed as several different isoforms (PlGF-1, -2, -3, and -4).11 Expression of PlGF is primarily in the syncitiotrophoblast layer of the placenta, which is in direct contact with maternal circulation.12 Placental growth factor binds to Flt1 but not to KDR.13 Though PlGF expression induces angiogenic activity, PlGF knockout mice do not exhibit placental or embryonic angiogenic defects.14

As gestation progresses, placental cytotrophoblasts participate in pseudovasculogenesis or maternal spiral artery remodeling. During pseudovasculogenesis, cytotrophoblasts leave the trophoblast basement membrane and migrate to and invade the uterine spiral arteries and decidual arterioles. At this stage, cytotrophoblasts undergo an epithelial-to-endothelial phenotypic transformation.15 Invasive cytotrophoblasts downregulate the expression of epithelial cell adhesion molecules, such as E-cadherin and α6β4, and begin expressing endothelial cell-specific adhesion molecules such as vascular endothelial-cadherin and αVβ3.16 Replacement of the endothelial layer of uterine spiral arteries decreases resistance in these blood vessels and thereby increases blood flow to the placenta. This process is critical to provide nutrients and oxygen to the developing placenta and fetus.17 Maternal spiral artery remodeling is also thought to be regulated by angiogenic factors Tie-1 and Tie-2.18 More work is needed to uncover the mechanisms underlying the progression from vasculogenesis to angiogenesis to pseudovasculogenesis in normal placentation and the reasons for maternal tolerance of cytotrophoblast invasion.

Abnormal Angiogenesis in Preeclampsia

In preeclamptic patients, high circulating levels of anti-angiogenic factors produced by the placenta contribute to maternal endothelial dysfunction and the clinical syndrome of preeclampsia. Placental expression and circulating levels of soluble Flt1 (sFLT1) and soluble endoglin (sEng) are markedly increased in preeclamptic patients.18–21 Elevation of these factors precedes the onset of clinical symptoms of preeclampsia and is correlated with disease severity.18, 20, 22–23 Both sFlt1 and sEng are truncated variants of cell surface receptors for angiogenic factors.

Soluble Flt1 is a truncated splice variant of VEGF receptor Flt1 lacking the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains.24 Soluble Flt1 is made in higher than normal quantities by the placenta beginning approximately 5 weeks prior to onset of preeclampsia.20 It is believed to compromise angiogenesis by binding to circulating VEGF and PlGF and inhibiting their mitogenic and homoestatic actions on endothelial cells.24–25 Pregnant rats administered exogenous sFlt1 via adenoviral vector develop characteristic symptoms of preeclampsia including hypertension, proteinuria, and glomerular endotheliosis.3 In non-pregnant mice, antibodies against VEGF have been shown to induce glomerular endothelial damage and proteinuria.26 Furthermore, in vitro studies have shown that exogenous antibodies against sFlt1 can reverse the antiangiogenic state in human preeclamptic plasma.25 Soluble Flt1 levels are also thought to contribute to the increased risk of preeclampsia in molar pregnancies27–28 and twin pregnancies.29 The use of vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors in cancer patients for the treatment of cancer-related angiogenesis has been associated with hypertension, proteinuria, glomerular endothelial damage, elevated circulating liver enzymes, cerebral edema, and reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy - features resembling those found in human preeclampsia and eclampsia.30–32 These studies point to the central role of sFlt1 and impaired VEGF signaling in the development of preeclampsia.

Recently, several variants of sFlt1 have been discovered, including sFlt1–14, which is expressed only in primates.33 Soluble Flt1–14 expression is increased dramatically in patients with preeclampsia.33–34 It is produced primarily by abnormal clusters of degenerative syncitiotrophoblasts, known as syncitial knots.33 Soluble Flt1–14 is the predominant VEGF inhibiting protein produced by the placenta and is capable of neutralizing VEGF activity in distant organs implicated in preeclampsia, such as the kidney.33 It has been proposed that sFlt1–14 may have evolved in humans to protect organs from adverse VEGF signaling. Several pathways have been proposed to regulate sFlt1 production, including placental hypoxia, genetic abnormalities, oxidative stress, inflammation, and deficient catechol-O-methyl transferase, however no consensus has been reached.14

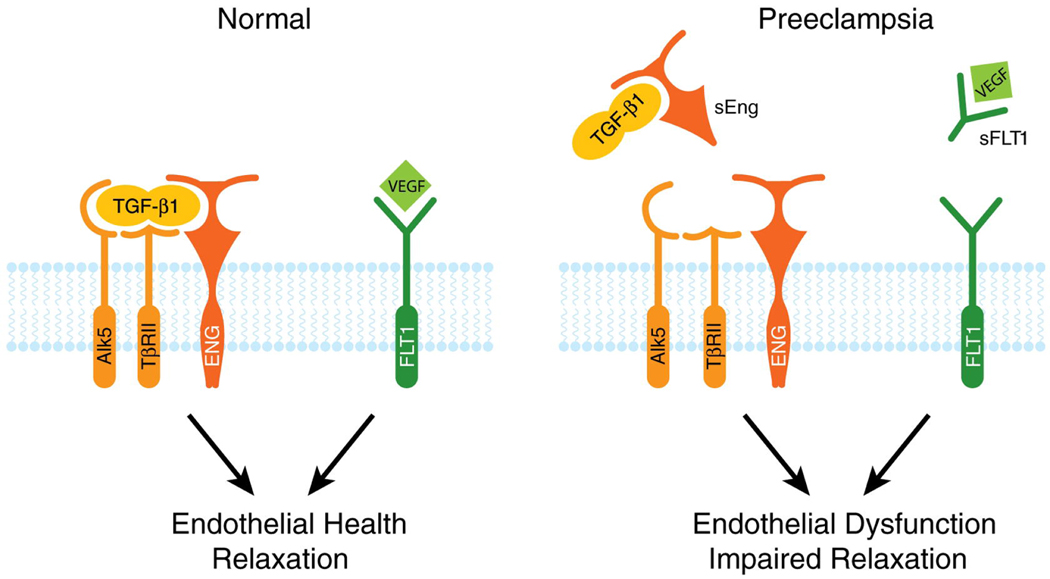

Although sFlt1 plays an important role in preeclampsia pathogenesis, it is unlikely that sFlt1 levels alone govern disease onset. Soluble endoglin (sEng), a truncated form of endoglin (CD105), is upregulated in preeclampsia and acts in concert with sFlt1 to cause endothelial dysfunction.35 Similar to sFlt1, circulating sEng levels are elevated weeks before preeclampsia onset.18 Endoglin is a cell surface receptor that binds and to and antagonizes TGF-β.9 Animals treated with both sFlt1 and sEng display severe signs of preeclampsia including HELLP syndrome, hemolysis and thrombocytopenia.35 The effects of sEng can be mediated by interference with nitric-oxide mediated vasodilation, suggesting that NO production is downstream of sEng.36–37 (See Figure 1)

Figure 1. sFlt1 and sEng Causes Endothelial Dysfunction by Antagonizing VEGF and TGF-β1 signaling.

There is mounting evidence that VEGF and TGF-β1 are required to maintain endothelial health in several tissues including the kidney and perhaps the placenta. During normal pregnancy, vascular homeostasis is maintained by physiological levels of VEGF and TGF-β1 signaling in the vasculature. In preeclampsia, excess placental secretion of sFlt1 and sEng (two endogenous circulating anti-angiogenic proteins) inhibits VEGF and TGF-β1 signaling respectively in the vasculature. This results in endothelial cell dysfunction, including decreased prostacyclin, nitric oxide production and release of procoagulant proteins. Figure reproduced with permission from Karumanchi et al.59

Role of Genetics in Preeclampsia

Although the risk factors for preeclampsia are both genetic and environmental, the presence of preeclampsia in first degree relatives increases a woman’s risk of preeclampsia by 2- to 4-fold.38–39 Genetic factors may play an important role in the angiogenic imbalance found in patients with preeclampsia. Recently, several polymorphisms in sFlt1 and VEGF have been associated with severity of preeclampsia.40–41 Patients with the VEGF 936 C/T genotype have been shown to have significantly lower VEGF plasma levels than subjects carrying the VEGF 936 C/C genotype.42 Another group has found that women carrying the G-allele of the VEGF 405G/C polymorphism have a decreased risk for developing severe preeclampsia43 and women carrying the A allele of the VEGF 2578C/A polymorphism face an accelerated disease progression.44 Although circulating PlGF, sFlt1, and sEng levels have been shown to be important markers of preeclampsia, no causal mutations in these genes associated with preeclampsia have been identified so far.45 However, women with trisomy 13 fetuses have a higher incidence of preeclampsia,46 suggesting that gene dosage or copy number variation may contribute to the development of preeclampsia. Notably, the Flt1 gene is located on chromosome 13.

There is some evidence to suggest that in addition to maternal genotype, paternal (or fetal) genotype may also contribute to risk of preeclampsia. The risk of fathering a preeclamptic pregnancy is increased among males who fathered a preeclamptic pregnancy with a different partner.47 Also, men who are born from a pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia are at a higher risk of fathering a preeclamptic pregnancy.48 To explain the contribution of paternal (fetal) genes in preeclampsia, several groups have proposed the genetic conflict hypothesis. According to the genetic conflict hypothesis, fetal genes contributed by the father are selected to increase uteroplacental bloodflow and deliver nutrients to the fetus while maternal genes are selected to limit blood flow to the fetus.49 An abnormality in the interaction between the fetus and the mother during pregnancy may contribute to the development of preeclampsia. One theory is that maternal immune cells in the decidua interact with specific trophoblast cells from the fetal placenta to mediate, and in some cases limit, fetal trophoblast invasion of the decidua.50 This interaction takes place between the killer immunoglobulin receptor on the maternal immune cell and the HLA receptor on the fetal trophoblast. Mothers carrying an inhibitory KIR (AA genotype) have been reported to be at an increased risk for preeclampsia when the fetus had a HLA-C2 allotype, a combination that is associated with impaired trophoblast invasion.51 Other groups have suggested that paternal imprinting at the STOX1 gene locus may contribute to preeclampsia.52

The Genetics of Preeclampsia Collaborative (GOPEC) study currently ongoing in Great Britain may shed light on genetic factors predisposing women to preeclampsia once its results are made public.2 This study and others are using unbiased approaches such as genome wide association studies, whole genome exon capture and sequencing approaches to identify causal genetic changes in preeclampsia.

Clinical Significance

As the role of angiogenic imbalance in preeclampsia becomes more clear, new avenues for diagnosis, predication, and therapy may become available. Automated immunoassays for sFlt-1 and PlGF have been recently developed for in vitro diagnostic testing of preeclampsia.53–54 The PlGF/sEng ratio has been shown to have an excellent predictive performance for the prediction of early-onset preeclampsia, with very high likelihood ratios for a positive test result and very low likelihood ratios for a negative test result.55 In preeclamptic patients, changes in the maternal plasma sEng and PlGF levels may also be predictive for a small for gestational age (SGA) neonate.56 Therapeutic strategies addressing the angiogenic imbalance in preeclampsia have also been suggested. In a rat model, treatment with VEGF-121 has been shown to improve glomerular filtration rate and endothelial function and reduce high blood pressure associated with placental ischemia57 and sFlt1 overexpression.58 In the future, therapeutic strategies addressing the angiogenic imbalance found in preeclampsia may significantly reduce maternal and neonatal mortality associated with this disease.

Conclusion

Substantial evidence now supports the role of sFlt1 and other soluble anti-angiogenic proteins in preeclampsia. Several important questions remain to be explored, however. Do polymorphisms, copy number variations, or epigenetic changes affect the balance of angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors produced by the placenta in preeclampsia? Are paternal (or fetal) genes relevant to maternal preeclampsia - if so, which genes are involved? More work is also needed to further define the regulation of placenta vascular development and expression of these angiogenic factors in normal and diseased pregnancies. As we continue studying preeclampsia and the pathways involved in this disease, hopefully it will become possible to create diagnostic tools that can detect preeclampsia before the onset of clinical symptoms and develop therapies that change the course of the disease. Such interventions could significantly affect maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality, worldwide.

Acknowledgements

S.A.K. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. S.A.K. is supported by a Clinical Scientist Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and an Established Investigator grant from the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: SAK reports having served as a consultant to Abbott, Beckman Coulter, Roche, and Johnson & Johnson and having been named co-inventor on multiple provisional patents filed by Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for the use of angiogenesis-related proteins for the diagnosis and treatment of preeclampsia. These patents have been nonexclusively licensed to several companies.

References

- 1.Villar J, Abalos E, Nardin JM, Merialdi M, Carroli G. Strategies to prevent and treat preeclampsia: evidence from randomized controlled trials. Semin Nephrol. 2004 Nov;24(6):607–615. doi: 10.1016/s0270-9295(04)00132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang A, Rana S, Karumanchi SA. Preeclampsia: the role of angiogenic factors in its pathogenesis. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009 Jun;24:147–158. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00043.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S, et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(5):649–658. doi: 10.1172/JCI17189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bdolah Y, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Angiogenic imbalance in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia: newer insights. Semin Nephrol. 2004 Nov;24(6):548–556. doi: 10.1016/s0270-9295(04)00125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zygmunt M, Herr F, Munstedt K, Lang U, Liang OD. Angiogenesis and vasculogenesis in pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003 Sep 22;110 Suppl 1:S10–S18. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(03)00168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrara N, Gerber HP. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in angiogenesis. Acta Haematol. 2001;106(4):148–156. doi: 10.1159/000046610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsatsaris V, Goffin F, Munaut C, Brichant JF, Pignon MR, Noel A, et al. Overexpression of the soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor in preeclamptic patients: pathophysiological consequences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003 Nov;88(11):5555–5563. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shibuya M. Structure and function of VEGF/VEGF-receptor system involved in angiogenesis. Cell Struct Funct. 2001;26(1):25–35. doi: 10.1247/csf.26.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maharaj AS, Walshe TE, Saint-Geniez M, Venkatesha S, Maldonado AE, Himes NC, et al. VEGF and TGF-beta are required for the maintenance of the choroid plexus and ependyma. J Exp Med. 2008 Feb 18;205(2):491–501. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrara N, Davis-Smyth T. The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocr Rev. 1997 Feb;18(1):4–25. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.1.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torry DS, Mukherjea D, Arroyo J, Torry RJ. Expression and function of placenta growth factor: implications for abnormal placentation. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2003 May;10(4):178–188. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(03)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuroda M, Oka T, Oka Y, Yamochi T, Ohtsubo K, Mori S, et al. Colocalization of vascular endothelial growth factor (vascular permeability factor) and insulin in pancreatic islet cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995 Nov;80(11):3196–3200. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.11.7593426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmeliet P, Moons L, Luttun A, Vincenti V, Compernolle V, De Mol M, et al. Synergism between vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor contributes to angiogenesis and plasma extravasation in pathological conditions. Nat Med. 2001 May;7(5):575–583. doi: 10.1038/87904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinberg G, Khankin EV, Karumanchi SA. Angiogenic factors and preeclampsia. Thromb Res. 2009;123 Suppl 2:S93–S99. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(09)70020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Y, Fisher SJ, Janatpour M, Genbacev O, Dejana E, Wheelock M, et al. Human cytotrophoblasts adopt a vascular phenotype as they differentiate. A strategy for successful endovascular invasion? J Clin Invest. 1997;99(9):2139–2151. doi: 10.1172/JCI119387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Y, Damsky CH, Fisher SJ. Preeclampsia is associated with failure of human cytotrophoblasts to mimic a vascular adhesion phenotype. One cause of defective endovascular invasion in this syndrome? J Clin Invest. 1997;99(9):2152–2164. doi: 10.1172/JCI119388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maynard S, Epstein FH, Karumanchi SA. Preeclampsia and angiogenic imbalance. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:61–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.110106.214058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, Yu KF, Maynard SE, Sachs BP, et al. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2006 Sep 7;355(10):992–1005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S, et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest. 2003 Mar;111(5):649–658. doi: 10.1172/JCI17189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, et al. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004 Feb 12;350(7):672–683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venkatesha S, Toporsian M, Lam C, Hanai J, Mammoto T, Kim YM, et al. Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nat Med. 2006 Jun;12(6):642–649. doi: 10.1038/nm1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hertig A, Berkane N, Lefevre G, Toumi K, Marti HP, Capeau J, et al. Maternal serum sFlt1 concentration is an early and reliable predictive marker of preeclampsia. Clin Chem. 2004 Sep;50(9):1702–1703. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.036715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Kim YM, Kim GJ, Kim MR, Espinoza J, et al. Plasma soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 concentration is elevated prior to the clinical diagnosis of pre-eclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005 Jan;17(1):3–18. doi: 10.1080/14767050400028816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kendall RL, Thomas KA. Inhibition of vascular endothelial cell growth factor activity by an endogenously encoded soluble receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(22):10705–10709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmad S, Ahmed A. Elevated placental soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 inhibits angiogenesis in preeclampsia. Circ Res. 2004 Oct 29;95(9):884–891. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147365.86159.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugimoto H, Hamano Y, Charytan D, Cosgrove D, Kieran M, Sudhakar A, et al. Neutralization of Circulating Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) by Anti-VEGF Antibodies and Soluble VEGF Receptor 1 (sFlt-1) Induces Proteinuria. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(15):12605–12608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanter D, Lindheimer MD, Wang E, Borromeo RG, Bousfield E, Karumanchi SA, et al. Angiogenic dysfunction in molar pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Feb;202(2):184, e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koga K, Osuga Y, Tajima T, Hirota Y, Igarashi T, Fujii T, et al. Elevated serum soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) level in women with hydatidiform mole. Fertil Steril. 2009 Mar 6; doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bdolah Y, Lam C, Rajakumar A, Shivalingappa V, Mutter W, Sachs BP, et al. Twin pregnancy and the risk of preeclampsia: bigger placenta or relative ischemia? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Apr;198(4):428, e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.10.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eremina V, Jefferson JA, Kowalewska J, Hochster H, Haas M, Weisstuch J, et al. VEGF inhibition and renal thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2008 Mar 13;358(11):1129–1136. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel TV, Morgan JA, Demetri GD, George S, Maki RG, Quigley M, et al. A preeclampsia-like syndrome characterized by reversible hypertension and proteinuria induced by the multitargeted kinase inhibitors sunitinib and sorafenib. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Feb 20;100(4):282–284. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamba T, McDonald DM. Mechanisms of adverse effects of anti-VEGF therapy for cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007 Jun 18;96(12):1788–1795. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sela S, Itin A, Natanson-Yaron S, Greenfield C, Goldman-Wohl D, Yagel S, et al. A novel human-specific soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1: cell-type-specific splicing and implications to vascular endothelial growth factor homeostasis and preeclampsia. Circ Res. 2008 Jun 20;102(12):1566–1574. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.171504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas CP, Andrews JI, Raikwar NS, Kelley EA, Herse F, Dechend R, et al. A recently evolved novel trophoblast-enriched secreted form of fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 variant is up-regulated in hypoxia and preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Jul;94(7):2524–2530. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venkatesha S, Toporsian M, Lam C, Hanai JI, Mammoto T, Kim YM, et al. Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nat Med. 2006 Jul;12(6):642–649. doi: 10.1038/nm1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Podjarny E, Losonczy G, Baylis C. Animal models of preeclampsia. Semin Nephrol. 2004 Nov;24(6):596–606. doi: 10.1016/s0270-9295(04)00131-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandrim VC, Palei AC, Metzger IF, Gomes VA, Cavalli RC, Tanus-Santos JE. Nitric oxide formation is inversely related to serum levels of antiangiogenic factors soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 and soluble endogline in preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2008 Aug;52(2):402–407. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.115006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carr DB, Epplein M, Johnson CO, Easterling TR, Critchlow CW. A sister's risk: family history as a predictor of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Sep;193(3 Pt 2):965–972. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carr DB, Newton KM, Utzschneider KM, Tong J, Gerchman F, Kahn SE, et al. Preeclampsia and risk of developing subsequent diabetes. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2009 Aug;28(4):435–447. doi: 10.3109/10641950802629675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Srinivas SK, Morrison AC, Andrela CM, Elovitz MA. Allelic variations in angiogenic pathway genes are associated with preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Mar 9; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papazoglou D, Galazios G, Koukourakis MI, Panagopoulos I, Kontomanolis EN, Papatheodorou K, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene polymorphisms and pre-eclampsia. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004 May;10(5):321–324. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ranheim T, Staff AC, Henriksen T. VEGF mRNA is unaltered in decidual and placental tissues in preeclampsia at delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(2):93–98. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.080002093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banyasz I, Szabo S, Bokodi G, Vannay A, Vasarhelyi B, Szabo A, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of vascular endothelial growth factor in severe pre-eclampsia. Mol Hum Reprod. 2006 Apr;12(4):233–236. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Widmer M, Villar J, Benigni A, Conde-Agudelo A, Karumanchi SA, Lindheimer M. Mapping the theories of preeclampsia and the role of angiogenic factors: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Jan;109(1):168–180. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000249609.04831.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mutze S, Rudnik-Schoneborn S, Zerres K, Rath W. Genes and the preeclampsia syndrome. J Perinat Med. 2008;36(1):38–58. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2008.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tuohy JF, James DK. Pre-eclampsia and trisomy 13. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992 Nov;99(11):891–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb14436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lie RT, Rasmussen S, Brunborg H, Gjessing HK, Lie-Nielsen E, Irgens LM. Fetal and maternal contributions to risk of pre-eclampsia: population based study. BMJ. 1998 May 2;16(7141):1343–1347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7141.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Esplin MS, Fausett MB, Fraser A, Kerber R, Mineau G, Carrillo J, et al. Paternal and Maternal Components of the Predisposition to Preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2001 March 22;344(12):867–872. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103223441201. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haig D. Genetic conflicts of pregnancy and childhood. In: Stearns SC, editor. Evolution in health and in disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roberts JM, Gammill HS. Preeclampsia: recent insights. Hypertension. 2005 Dec;46(6):1243–1249. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000188408.49896.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hiby SE, Walker JJ, O'Shaughnessy KM, Redman CW, Carrington M, Trowsdale J, et al. Combinations of maternal KIR and fetal HLA-C genes influence the risk of preeclampsia and reproductive success. J Exp Med. 2004 Oct 18;200(8):957–965. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Dijk M, Mulders J, Poutsma A, Konst AA, Lachmeijer AM, Dekker GA, et al. Maternal segregation of the Dutch preeclampsia locus at 10q22 with a new member of the winged helix gene family. Nat Genet. 2005 May;37(5):514–519. doi: 10.1038/ng1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ohkuchi A, Hirashima C, Suzuki H, Takahashi K, Yoshida M, Matsubara S, et al. Evaluation of a new and automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay for plasma sFlt-1 and PlGF levels in women with preeclampsia. Hypertens Res. 2010 Feb 12; doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sunderji S, Gaziano E, Wothe D, Rogers LC, Sibai B, Karumanchi SA, et al. Automated assays for sVEGF R1 and PlGF as an aid in the diagnosis of preterm preeclampsia: a prospective clinical study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jan;202(1):40, e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kusanovic JP, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Erez O, Mittal P, Vaisbuch E, et al. A prospective cohort study of the value of maternal plasma concentrations of angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors in early pregnancy and midtrimester in the identification of patients destined to develop preeclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009 Nov;22(11):1021–1038. doi: 10.3109/14767050902994754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Romero R, Nien JK, Espinoza J, Todem D, Fu W, Chung H, et al. A longitudinal study of angiogenic (placental growth factor) and anti-angiogenic (soluble endoglin and soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1) factors in normal pregnancy and patients destined to develop preeclampsia and deliver a small for gestational age neonate. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008 Jan;21(1):9–23. doi: 10.1080/14767050701830480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gilbert JS, Verzwyvelt J, Colson D, Arany M, Karumanchi SA, Granger JP. Recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor 121 infusion lowers blood pressure and improves renal function in rats with placentalischemia-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2010 Feb;55(2):380–385. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.141937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Z, Zhang Y, Ying Ma J, Kapoun AM, Shao Q, Kerr I, et al. Recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor 121 attenuates hypertension and improves kidney damage in a rat model of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2007 Oct;50(4):686–692. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.092098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karumanchi SA, Epstein FH. Placental ischemia and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1: cause or consequence of preeclampsia? Kidney Int. 2007 May;71(10):959–961. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]