Abstract

In solvolysis studies using Grunwald-Winstein plots, dispersions were observed for substrates with aromatic rings at the α-carbon. Several examples for the unimolecular solvolysis of monoaryl benzylic derivatives and related diaryl- or naphthyl- substituted derivatives have now been reported, where the application of the aromatic ring parameter (I) removes this dispersion. A recent claim suggesting the presence of an appreciable nucleophilic component to the I scale, has now been shown, in a review of the solvolysis of highly-hindered alkyl halides, to be unlikely to be correct. Attention is now focused on the application of the hI term for the solvolysis of compounds containing a double bond in the vicinity of any developing carbocation. Available specific rates of solvolysis (plus some new values) at 25°C of cinnamyl chloride, cinnamyl bromide, cinnamoyl chloride, p-chlorocinnamoyl chloride, and p-nitrocinnamoyl chloride are analyzed using the simple and extended (including the hI term) Grunwald-Winstein equations.

1. Introduction

To commemorate the 60th anniversary of the development of the simple Grunwald-Winstein equation [1], a review detailing its development and applications was recently published [2]. The linear free energy relationship (LFER) shown in equation 1, was developed in 1948 for the correlation of solvolysis reactions proceeding by an ionization (SN1 + E1) pathway [1]. In equation 1, k and k0 are the specific rates of solvolysis of the substrate under study in a given solvent and in the standard solvent, respectively; m is the sensitivity towards changes in the solvent ionizing power Y (initially set at unity for tert-butyl chloride solvolyses), and c is a constant (residual) term.

| (1) |

It was realized [3] that as the solvolyses of 1-, and 2-adamantyl derivatives (Figure 1) cannot be subject to rearside nucleophilic participation and elimination, they could provide improved standard substrates for establishing scales of solvent ionizing power [4, 5] and listings of Yx values are available [6].

FIGURE 1.

1-, and 2-adamantyl derivatives.

For bimolecular (SN2 and/or E2) reactions, an additional term involving the sensitivity (l) to changes in solvent nucleophilicity (N) is added to equation 1, to give equation 2 [7].

| (2) |

The development of solvent nucleophilicity scales has been briefly reviewed [2, 8] and it has also been reviewed in considerable depth in a book chapter [9]. At the present time the NT scale [2, 8-10] with S-methyldibenzothiophenium ion (MeDBTh+) as the standard substrate has become the recommended standard [2] for considerations of solvent nucleophilicity.

Three approaches have been proposed to correct for dispersions observed in Grunwald-Winstein plots when aromatic rings are bonded to the carbon that is developing appreciable positive charge at the transition state or when substrates solvolyze with neighboring aryl group participation. Bentley et al. [11] favored the use of p-methoxybenzyl chloride as a similarity model to correlate the solvolyses of α-aryl halides. Liu et al [12, 13] also using a similarity model approach developed YBnX scales for each leaving group X and YxBnX scales [14] for x aromatic rings entering into conjugation with the reaction center. Early on, we pointed out [15] that only negligible to moderate improvements result from replacing the Yx scale by a “specialized” scale and the considerable effort involved in developing the new scales is not justified. Fujio, Tsuno and co-workers proposed [16] a second approach for solvolyses that proceed via anchimeric assistance (kΔ) and developed a scale (YΔ) derived from 2-methyl-2-(p-methoxyphenyl)propyl toluene-p-sulfonate solvolyses. We have favored a third, more general avenue by developing [17] an aromatic ring parameter (I), where an appropriate sensitivity h is added to Grunwald-Winstein equations 1 and 2, to give equations 3 and 4. This approach avoids the non trivial task of choosing a closely related similarity model, furthermore, it can be used with multiple aromatic rings in conjugation with the developing carbocationic center, and to correlate solvolysis involving a 1,2-aryl shift [2].

| (3) |

| (4) |

Recently, Martins and coworkers [18] applied equation 4 to the specific rates of solvolysis of five moderately-hindered tertiary alkyl halides (substrates mostly with the absence of π-electrons) and found the sensitivities (h) to changes in the aromatic-ring parameter (I) were sometimes positive and sometimes negative. They suggested that the negative h values arose because I was not a pure parameter and proposed that it included a solvent nucleophilicity component [18]. After a thorough analysis of the available specific rates of solvolyses of 30 highly-hindered tertiary alkyl derivatives, we concluded in a recent review [19] that it appears that the apparent utility of the hI term for substrates not having appropriately placed π-electrons is an artifact resulting from moderate multicollinearity that is present between the I values and a linear combination of NT and YX values.

Cinnamyl chloride is one of many chemicals that produce allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) in humans [20] and yet it is a common important chemical intermediate that has found use in a variety of pharmaceutical compositions, fragrance, and flavoring agents. The analysis of the substituent effects on carbocation reactivity using the Hammett plot for the chlorine exchange of substituted cinnamyl chlorides [21] and studies of the secondary deuterium isotope effect [22] implied electron-donating conjugation through the double bond in a loose SN1 transition state. Koo et al. have analyzed the solvolytic rate constants and product selectivities (S) of cinnamyl chloride [23] and cinnamyl bromide [24] in a number of binary mixtures of water with ethanol, methanol, acetone, and 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE). The close similarity of solvent kinetic isotope effects, rate-rate profiles of solvent effects on reactivity, and similar selectivity data to p-methoxybenzyl chloride [11, 25] made the authors conclude that the solvolyses of cinnamyl halides can be explained by product formation incorporating a general base-catalyzed nucleophilic attack on a contact ion-pair [23, 24]. Cinnamyl bromide was subject to electrochemical reduction using cyclic voltammetry and controlled-potential electrolysis [26] where it was shown that the substrate could be reduced to a resonance-stabilized cinnamyl radical, which could further be reduced to a carbanion depending upon the selected potential.

Cinnamoyl derivatives are used to produce compounds that have shown promising antifungal, antibacterial [27], and anticancer [28] activity. Koo and co-workers also studied the solvolyses of substituted cinnamoyl chlorides [29] in aqueous binary mixtures of ethanol, methanol, acetone, and TFE, and in TFE-EtOH. Based on the examination of results obtained using their kinetic data in Hammett plot analysis and in exceedingly scattered Grunwald-Winstein plots, they proposed a dissociative SN2 pathway for three p-substituted cinnamoyl chlorides [29].

2. Results and Discussion

In this study, we present specific rates of solvolysis of cinnamyl chloride (1) at 25.0 °C in three aqueous ethanol (EtOH), three aqueous methanol (MeOH), one aqueous acetone, two aqueous TFE, and four TFE-EtOH mixtures. We reanalyze all available specific rates of solvolysis of cinnamyl chloride (1), cinnamyl bromide (2), cinnamoyl chloride (3), p-chlorocinnamoyl chloride (4), and p-nitrocinnamoyl chloride (5), in terms of the simple and extended Grunwald-Winstein equations (equations 1 and 2), and we also consider the extent to which these equations are improved on incorporation of the hI term (equations 3 and 4).

In Table 1, we report specific rate constants at 25.0 °C for the solvolyses of 1 in the aqueous binary mixtures of MeOH, EtOH, acetone, and TFE, and in TFE-EtOH. The specific rate constants for 1 in 97 and 90 TFE-H2O (%w/w) were determined at 3 different temperatures and an Arrhenius treatment allowed estimation of the specific rate at the higher 25.0 °C temperature, also presented in Table 1. Our measurements at 25.0 °C, when compared to those reported by Koo and coworkers [23] differ markedly (as shown in Table 1 and corresponding footnotes), by a factor of 5 in pure EtOH, by a factor of 3 in 90% EtOH (%v/v) and by a factor of 2 in 80% EtOH (%v/v). Furthermore, an acceptable 2% difference observed in the value of 80T-20E progressed to a much larger 30% difference in the 60T-40E value, then to a substantial 50% difference in the 40T-60E reported value, and culminated in a huge difference of 70% observed in the 20T-80E mixture. The observations of significant deviations seen only in EtOH-rich mixtures indicated that the deviant behavior was a general characteristic (in this particular case) of that solvent. We minimized experimental error by designing mechanical mixing for uniform consistency, using ACS reagent grade solvents, repeating the titrimetric procedures using different batches of EtOH, and the key reactions were also repeated during different months to verify that the same trends persisted. The specific rates for the EtOH containing mixtures reported in Table 1 are the averages of at least four independent kinetic runs.

TABLE 1.

Specific rates of solvolysis (k)a of 1, in several binary solvents at 25.0 °C and literature values for (NT) and (YCl).

| Solvent (%)b | 1 @ 25.0 °C; 105k, s-1 | NTl | YClm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100% MeOH | 0.905 | 0.17 | -1.2 |

| 90% MeOH | 4.87 | -0.01 | -0.20 |

| 80% MeOH | 21.5 | -0.06 | 0.67 |

| 100% EtOH | 0.416c | 0.37 | -2.50 |

| 90% EtOH | 2.28d | 0.16 | -0.90 |

| 80% EtOH | 8.05e | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 90% Acetone | 0.00731 | -0.35 | -2.39 |

| 97% TFE (w/w) | 488f | -3.30 | 2.83 |

| 90% TFE (w/w) | 626g | -2.55 | 2.85 |

| 80T-20E | 83.5h | -1.76 | 1.89 |

| 60T-40E | 14.5i | -0.94 | 0.63 |

| 40T-60E | 3.52j | -0.34 | -0.48 |

| 20T-80E | 1.12k | 0.08 | -1.42 |

Determined titrimetrically; typical error ±4%.

Substrate concentration of ca. 0.0052 M; binary solvents on a volume-volume basis at 25.0 °C, except for TFE-H2O solvents which are on a weight-weight basis. T-E are TFE-ethanol mixtures.

Value reported in Table 1 is the average obtained using 105 k (s-1) values at 25.0 °C of 0.409, 0.420, 0.418, and 0.417 from four independent runs. A value of 0.0839 × 10-5 s-1 is reported in the literature [23].

Value reported in Table 1 is the average obtained using 105 k (s-1) values at 25.0 °C of 2.26, 2.27, 2.30, and 2.30 from four independent runs. A value of 0.970 × 10-5 s-1 is reported in the literature [23].

Value reported in Table 1 is the average obtained using 105 k (s-1) values at 25.0 °C of 8.03, 8.03, 8.03, and 8.11 from four independent runs. A value of 4.73 × 10-5 s-1 has been reported in the literature [23].

Calculated from Arrhenius plots using 105 k (s-1) values at 0.0°, -5.0°, and -10.0 °C of 17.8, 8.9, and 4.0.

Calculated from Arrhenius plots using 105 k (s-1) values at 0.0°, -5.0°, and -10.0 °C of 23.9, 10.2, and 5.4.

Value reported in Table 1 is the average obtained using 105 k (s-1) values at 25.0 °C of 82.7, 83.1, 83.8, and 84.2 from four independent runs. A value of 84.8 × 10-5 is reported in the literature [23].

Value reported in Table 1 is the average obtained using 105 k (s-1) values at 25.0 °C of 14.1, 14.6, 14.6, and 14.7 from four independent runs. A value of 10.4 × 10-5 is reported in the literature [23].

Value reported in Table 1 is the average obtained using 105 k (s-1) values at 25.0 °C of 3.48, 3.50, 3.55, and 3.56 from four independent runs. A value of 1.91 × 10-5 is reported in the literature [23].

Value reported in Table 1 is the average obtained using 105 k (s-1) values at 25.0 °C of 1.09, 1.10, 1.13, and 1.14 from four independent runs. A value of 0.353 × 10-5 is reported in the literature [23].

The specific rate constants for solvolyses of 1 in solvents other than EtOH are within an acceptable ± 7% range of values reported by Koo and coworkers [23]. Hence, the new data in the thirteen solvents listed in Table 1 were combined with the nineteen reported values [23] in solvents other than ethanol. As reported in Table 2 for the 32 solvents, we obtained a fair linear correlation using equation 1, with m = 0.76 ± 0.03, c = -0.25 ± 0.08, 0.975 for the correlation coefficient, and 571 for the F-test value. Use of equation 2 leads to an essentially zero l value (0.09 ± 0.09) associated with a 0.29 probability that the lNT term is statistically insignificant. In contrast, use of equation 3, displays a m value of 0.79 ± 0.03, a h value of 0.47 ± 0.20 (with a 0.03 probability of insignificance) and with a negligible improvement in the correlation coefficient (0.979) when compared to the solution obtained using equation 1. As observed in Table 2, analysis of the solvolysis of 1 is best carried out in terms of equation 4, with a considerably higher correlation coefficient of 0.987, a l value of 0.33 ± 0.08, a m value of 0.91 ± 0.04, a h value of 0.97 ± 0.21, a c value of 0.20 ± 0.07, and a F-test value of 340.

TABLE 2.

Correlation of the specific rates of reaction of 1, at 25.0 °C using equations 1-4.

| Substrate | na | lb | mb | hb | cc | Rd | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1; 25.0 °C | 32f | 0.76 ± 0.03 | -0.25 ± 0.08 | 0.975 | 571 | ||

| 0.09 ± 0.09 (0.29)g | 0.79 ± 0.04 | -0.21 ± 0.09 | 0.976 | 288 | |||

| 0.79 ± 0.03 | 0.47 ± 0.20 (0.03)g | -0.30 ± 0.08 | 0.979 | 331 | |||

| 0.33 ± 0.08 | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 0.97 ± 0.21 | -0.20 ± 0.07 | 0.987 | 340 | ||

| 31h | 0.79 ± 0.03 | -0.33 ± 0.08 | 0.979 | 664 | |||

| 0.09 ± 0.08 (0.26)g | 0.82 ± 0.04 | -0.29 ± 0.09 | 0.980 | 337 | |||

| 0.82 ± 0.03 | 0.49 ± 0.17 | -0.38 ± 0.07 | 0.984 | 416 | |||

| 0.33 ± 0.06 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 1.00 ± 0.16 | -0.29 ± 0.06 | 0.992 | 551 | ||

| 30i | 0.73 ± 0.03 | -0.15 ± 0.08 | 0.977 | 594 | |||

| 0.06 ± 0.10 (0.53)g | 0.74 ± 0.04 | -0.13 ± 0.09 | 0.978 | 291 | |||

| 0.75 ± 0.03 | 0.37 ± 0.19 (0.07)g | -0.21 ± 0.08 | 0.980 | 327 | |||

| 0.36 ± 0.11 | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 0.88 ± 0.23 | -0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.986 | 295 |

Using data at 25.0 °C from Table 1; NT values from refs. [9, 10]; YCl values from refs.[5, 6]; the 70-0% MeOH, 80-10% Acetone, 100TFE, 70TFE(w/w), 50TFE(w/w) values are from ref. [23]; n is the number of solvents.

With associated standard error.

Accompanied by standard error of the estimate.

Correlation coefficient.

F-test value.

All solvents.

Probability that the contribution to the linear free energy relationship is insignificant.

Excluding 100EtOH.

In exactly the same solvents as 2.

Excluding the data point for 100 EtOH, the solvent with highest nucleophilicity and lowest ionizing power (favoring bimolecular reaction); the correlation using equation 4 in the remaining 31 solvents have l, m, and h values similar to those obtained with 32 solvents, but with a considerably improved correlation coefficient of 0.992 and a significantly higher F-test value of 551. The l (0.33), m (0.95), and h (1.00) values obtained for 1 in 31 solvents (Table 2), are very similar to l = 0.25 ± 0.06, m = 0.92 ± 0.03, and h = 0.88 ± 0.13, reported for p-methoxybenzyl chloride [30]; and l = 0.34 ± 0.15 (0.04 probability that the lNT term is statistically insignificant), m = 0.89 ± 0.04, and h = 0.92 ± 0.15 for 2,6-dimethylbenzoyl chloride [31], where we suggested that the nucleophilic solvation of the developing carbocation rather than a covalent involvement of the solvent molecule, is effective. This affirmation of appreciable nucleophilic solvation for 1 as indicated by the l value of 0.33 (in Table 2), is consistent with recent results showing that the p-methoxybenzyl carbocation is more stable that the cinnamyl carbocation but less stable that its p-methoxycinnamyl analog [32]. These results arose from a synthetic method involving a chlorosulfonyl isocyanate reaction with various alkyl allyl ethers to study carbocation stability in the solution phase, and using this newly developed procedure, the authors also showed that a cinnamyl carbocation is more stable than a benzylic carbocation and less stable than a 3° carbocation [32]. The h value reported in Table 2 of 1.00 ± 0.16 for 1 in 31 solvents, is also consistent with one aromatic ring easily entering into conjugation [17] with the developing resonance stabilized transition state. This possibility of neighboring π-bond stabilization of the developing carbocation (phenacyl effect) is confirmed on visual inspection of the 3-D structure of cinnamyl chloride (1’), shown in Figure 3, due to the perfect planarity of the ring and the adjacent vinylic double bond.

FIGURE 3.

3-D views of cinnamyl chloride (1’), cinnamoyl chloride (3’), and p-nitrocinnamoyl chloride (5’), computed using the KnowItAll® platform.

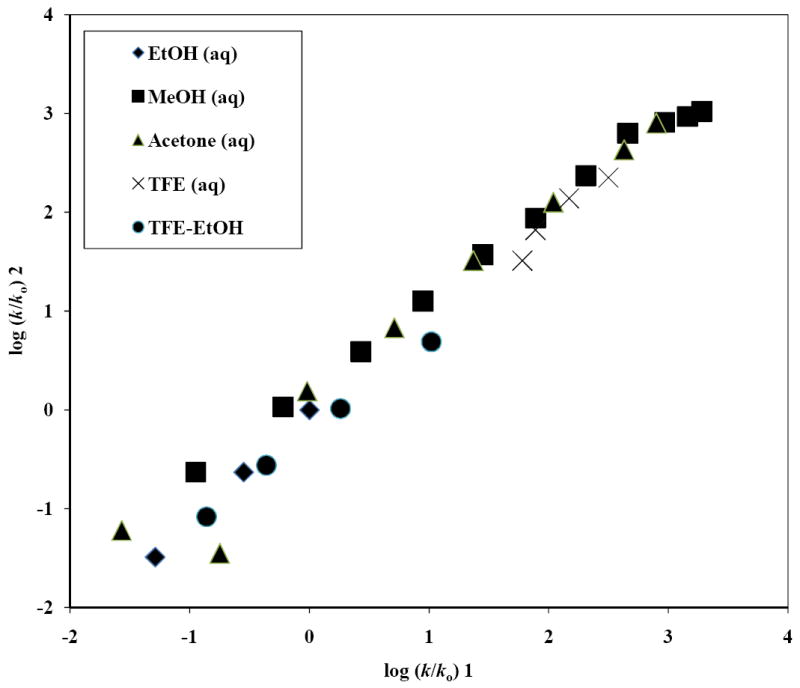

The previously reported specific rates of solvolysis at 25 °C for cinnamyl bromide (2) [24] are analyzed using equations 1-4. These results are reported in Table 3 for all 37 solvents and results are also tabulated for those obtained without the pure EtOH value (36 solvents). The slight improvements (for both 1 and 2) seen in the R and the F–test values on exclusion of the specific rates in 100 EtOH, and the similarities in trends observed in the numerical values for l, m, and h, (reported in Tables 2 and 3) for 1 and 2 in thirty identical solvents, are substantiated by the linear plot shown in Figure 4 of the log (k/ko) values for 1 against those for 2, with an excellent correlation coefficient of 0.989, F-test value of 1201, slope of 0.99 ± 0.03 and intercept of -0.02 ± 0.05. We can thus conclude that both, cinnamyl chloride and cinnamyl bromide solvolyze with nucleophilc solvation of the developing resonance stabilized SN1 transition state.

TABLE 3.

Correlation of the specific rates of reaction of 2, at 25.0 °C using equations 1-4.

| Substrate | na | lb | mb | hb | cc | Rd | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2; 25.0 °C | 37f | 0.76 ± 0.03 | -0.15 ± 0.08 | 0.973 | 616 | ||

| 0.14 ± 0.10 (0.17)g | 0.79 ± 0.04 | -0.11 ± 0.08 | 0.974 | 317 | |||

| 0.79 ± 0.04 | 0.33 ± 0.21 (0.12)g | -0.20 ± 0.08 | 0.975 | 323 | |||

| 0.51 ± 0.11 | 1.01 ± 0.05 | 1.13 ± 0.24 | -0.13 ± 0.06 | 0.985 | 354 | ||

| 36h | 0.78 ± 0.03 | -0.20 ± 0.08 | 0.972 | 577 | |||

| 0.13 ± 0.09 (0.17)g | 0.81 ± 0.04 | -0.16 ± 0.09 | 0.973 | 298 | |||

| 0.81 ± 0.03 | 0.37 ± 0.20 (0.08)g | -0.26 ± 0.08 | 0.974 | 311 | |||

| 0.54 ± 0.10 | 1.05 ± 0.05 | 1.23 ± 0.21 | -0.20 ± 0.06 | 0.987 | 403 | ||

| 30i | 0.75 ± 0.04 | -0.17 ± 0.09 | 0.970 | 440 | |||

| 0.11 ± 0.11 (0.30)g | 0.78 ± 0.05 | -0.12 ± 0.10 | 0.971 | 222 | |||

| 0.78 ± 0.04 | 0.40 ± 0.23 (0.09)g | -0.23 ± 0.09 | 0.973 | 238 | |||

| 0.49 ± 0.12 | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 1.14 ± 0.26 | -0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.983 | 255 |

Using data at 25.0 °C from ref. [24]; NT values from refs. [9, 10]; YBr values from ref. [6]; n is the number of solvents.

With associated standard error.

Accompanied by standard error of the estimate.

Correlation coefficient.

F-test value.

All solvents.

Probability that the contribution to the linear free energy relationship is insignificant.

Excluding 100EtOH.

In exactly the same solvents as 1.

FIGURE 4.

A plot of log (k/ko) for cinnamyl bromide (2) against log (k/ko) for cinnamyl chloride (1) in pure and binary solvents at 25 °C. This plot has a correlation coefficient of 0.989, F-test value of 1201, slope of 0.99 ± 0.03 and intercept of -0.02 ± 0.05.

Koo’s claim [24, 33] of the presence of a through conjugation of the ring π system with the reaction center in phenyl chlorothionoformate (PhOCSCl) was invalidated [34] lately as no evidence was found requiring inclusion of the h parameter for ionization reactions with only one aromatic ring on the nitrogen of carbamoyl chlorides, or for the solvolyses of the chloroformate, or chlorothionoformate proceeding by an addition-elimination (association-dissociation) mechanism.

The 3-D views for cinnamoyl chloride (3’) and p-nitrocinnamoyl chloride (5’) are shown in Figure 3 incorporating prior results [35] for the position of the halogen in the ground-state structure of acid chlorides. The 3-D images of 3’ and 5’ clearly attests to the planar conformation between the aromatic ring, the vinylic double bond, and the carbonyl group. Studies have shown that when cinnamoyl-based structures were synthesized and characterized by a syn disposition of the carbonyl group with the vinylic double bond, they specifically inhibited the enzymatic reactions associated with HIV-1 integrase (IN) [36].

The specific rate order reported [29] for the three p-substituted cinnamoyl chlorides is k (3) > k (4) > k (5) in the pure and binary aqueous mixtures of EtOH, MeOH, and acetone, and a broader rate order of k (3) > k (4) ≫ k (5) is reported in the aqueous TFE and the TFE-EtOH mixtures. The substantial rate decrease (of over a factor of 100) from 3 to 5 in TFE, 97 TFE, and 90 TFE, is attributed to the powerful inductive destabilizing ability of the p-nitro group when positive charge is developing at the reaction center, due to the coplanarity observed between the ring, the vinylic double bond, and the reaction center in the 3-D view of 5 (5’ in Figure 3).

For a meaningful comparison of the application of equations 1-4 to the specific rates of solvolysis of 3, 4, and 5, [29] it is important that the comparisons are made in identical solvents. A close examination of the data presented in Table 4 shows that for the three substrates in 24 common solvents, applications of equations 1 and 3 (without the lNT term) gave exceedingly poor correlation coefficients (R) and F-test values. This indicates that the correlations are very sensitive to solvent nucleophilicity, with a possibility for the further need of nucleophilic solvation [2, 17, 30, 31, 34, 37, 38] of the developing transition state.

TABLE 4.

Correlation of the specific rates of reaction of 3, 4, and 5, at 25.0 °C using equations 1-4.

| Substrate | na | lb | mb | hb | cc | Rd | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3; 25.0 °C | 24f | 0.39 ± 0.04 | -0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.913 | 110 | ||

| 0.19 ± 0.06 (0.01)g | 0.49 ± 0.05 | -0.12 ± 0.06 | 0.940 | 80 | |||

| 0.40 ± 0.04 | -0.05 ± 0.19 (0.80)g | -0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.913 | 53 | |||

| 0.31 ± 0.07 | 0.56 ± 0.05 | 0.48 ± 0.19 (0.02)g | -0.12 ± 0.06 | 0.956 | 70 | ||

| 4; 25.0 °C | 24f | 0.41 ± 0.05 | -0.14 ± 0.09 | 0.885 | 79 | ||

| 0.33 ± 0.05 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | -0.04 ± 0.06 | 0.961 | 128 | |||

| 0.41 ± 0.04 | -0.51 ± 0.21 (0.02)g | -0.09 ± 0.08 | 0.911 | 52 | |||

| 0.36 ± 0.07 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 0.12 ± 0.19 (0.56)g | -0.04 ± 0.06 | 0.962 | 83 | ||

| 5; 25.0 °C | 24f | 0.18 ± 0.08 | -0.16 ± 0.16 | 0.411 | 5 | ||

| 0.55 ± 0.08 | 0.51 ± 0.06 | 0.02 ± 0.08 | 0.894 | 42 | |||

| 0.17 ± 0.07 (0.02)g | -1.17 ± 0.34 | -0.07 ± 0.13 | 0.683 | 9 | |||

| 0.63 ± 0.11 | 0.50 ± 0.07 | -0.08 ± 0.29 (0.78)g | 0.02 ± 0.08 | 0.895 | 27 | ||

| 3; 25.0 °C | 22h | 0.40 ± 0.04 | -0.14 ± 0.07 | 0.922 | 114 | ||

| 0.17 ± 0.06 (0.01)g | 0.49 ± 0.05 | -0.10 ± 0.06 | 0.945 | 80 | |||

| 0.40 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.22 (0.53)g | -0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.924 | 56 | |||

| 0.37 ± 0.05 | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 0.89 ± 0.15 | -0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.982 | 163 | ||

| 4; 25.0 °C | 22h | 0.42 ± 0.04 | -0.09 ± 0.08 | 0.911 | 97 | ||

| 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.58 ± 0.03 | -0.02 ± 0.05 | 0.975 | 187 | |||

| 0.41 ± 0.04 | -0.34 ± 0.24 (0.17)g | -0.08 ± 0.08 | 0.920 | 52 | |||

| 0.43 ± 0.04 | 0.64 ± 0.03 | 0.53 ± 0.14 | -0.01 ± 0.04 | 0.987 | 221 | ||

| 5; 25.0 °C | 22h | 0.18 ± 0.08 | -0.07 ± 0.15 | 0.470 | 6 | ||

| 0.61 ± 0.06 | 0.49 ± 0.04 | 0.07 ± 0.06 | 0.941 | 73 | |||

| 0.17 ± 0.07 (0.02)g | -0.91 ± 0.40 | -0.05 ± 0.13 | 0.627 | 6 | |||

| 0.73 ± 0.07 | 0.56 ± 0.04 | 0.56± 0.20 (0.01)g | 0.08 ± 0.05 | 0.959 | 68 |

Determined titrimetrically; typical error ±4%.

Substrate concentration of ca. 0.0052 M; binary solvents on a volume-volume basis at 25.0 °C, except for TFE-H2O solvents which are on a weight-weight basis. T-E are TFE-ethanol mixtures.

Value reported in Table 1 is the average obtained using 105 k (s-1) values at 25.0 °C of 0.409, 0.420, 0.418, and 0.417 from four independent runs. A value of 0.0839 × 10-5 s-1 is reported in the literature [23].

Value reported in Table 1 is the average obtained using 105 k (s-1) values at 25.0 °C of 2.26, 2.27, 2.30, and 2.30 from four independent runs. A value of 0.970 × 10-5 s-1 is reported in the literature [23].

Value reported in Table 1 is the average obtained using 105 k (s-1) values at 25.0 °C of 8.03, 8.03, 8.03, and 8.11 from four independent runs. A value of 4.73 × 10-5 s-1 has been reported in the literature [23].

Data from ref. [29], no 40E, 40M values for 5;

Calculated from Arrhenius plots using 105 k (s-1) values at 0.0°, -5.0°, and -10.0 °C of 23.9, 10.2, and 5.4.

No T-E mixtures.

For compound 3 in the 24 solvents studied, use of equation 2 gives rise to a l value of 0.19 ± 0.06 with a probability of 0.01 that the lN term is statistically insignificant; a m value of 0.49 ± 0.05; -0.12 ± 0.06 for c; a correlation coefficient of 0.940 and a F-test of 80. On application of equation 4 to the 24 solvents studied for 3, there is a slight improvement in the value of R to 0.956, l = 0.31 ± 0.07, m = 0.56 ± 0.05, h = 0.48 ± 0.19 with a 0.02 probability that the hI term is statistically insignificant, c = -0.12 ± 0.06, and a F-test value of 70. With compound 4, use of equation 2 in the identical 24 solvents used in the calculations for 3, yields l = 0.33 ± 0.05, m = 0.59 ± 0.04, c = -0.04 ± 0.06, R = 0.961, and F-test = 128. Essentially no improvements are observed with the use of equation 4 (for 3), where l = 0.36 ± 0.07, m = 0.60 ± 0.05, h = 0.12 ± 0.19, c = -0.04 ± 0.06, R = 0.962, and F-test = 83. Use of equations 2 or 4 does not improve the immense scatter seen in the Grunwald-Winstein plots with the use of equations 1 or 3 for 5. Employing equation 2 for the same 24 solvents studied with 5, produce a l value of 0.55 ± 0.08, m = 0.51 ± 0.06, c = 0.02 ± 0.08, R = 0.894, and F-test = 42. Application of equation 4 to the 24 solvents used with 5 show no change in the scatter with l = 0.63 ± 0.11, m = 0.57 ± 0.04, h = -0.08 ± 0.29, c = -0.02 ± 0.08, R = 0.961, and F-test = 128.

There has been considerable discussion regarding the reactivity-selectivity trends in aqueous TFE and TFE-EtOH [39-41]. Additionally, for a number of substrates [2, 34, 42-48], there have been several instances where removal of the TFE-EtOH points have led to a considerable improvement of the goodness-of-fit parameters in Grunwald-Winstein linear free energy plots. Also presented in Table 4 are our correlation analysis results for 3, 4, and 5, with the exclusion of the data points in TFE-EtOH. This was done in order to evaluate the phenomena of dispersion commonly seen for the TFE-EtOH solvents [39-41] and this observation is probably due to the bulky nature of this solvent (when compared to aqueous TFE) [43]. In the case of the solvolysis of 3, omission of the two TFE-EtOH solvents (22 solvents) and use of equation 2 yields l = 0.17 ± 0.06 associated with a 0.01 probability of statistical insignificance, m = 0.49 ± 0.05, c = -0.10 ± 0.06, R = 0.945, and F-test = 80. There is considerable improvement of the goodness-of-fit parameters on application of equation 4 to the specific rates of solvolysis of 3 in 22 solvents. The significant improvement of R = 0.982, and F-test = 163, suggest that there is a need for nucleophilic solvation of the developing resonance stabilized carbocation with l = 0.37 ± 0.05, m = 0.60 ± 0.03, h = 0.89 ± 0.15, c = -0.08 ± 0.04. The similarities of the l, m, and h values (Tables 2 and 4) between cinnamyl (1) and cinnamoyl (3) chloride further suggest that the presence of a carbonyl oxygen has no major impact on either the amount of nucleophilic solvation needed to stabilize the developing carbocation or the amount of charge delocalized into the ring.

Analysis using equation 2 for the identical 22 solvents in solvolyses of 4 produces l = 0.30 ± 0.04, m = 0.58 ± 0.03, c = -0.02 ± 0.05, R = 0.975, and F-test = 187. Use of equation 4 improves the correlation coefficient significantly to 0.987 and the F-test is raised to 221. The values of l = 0.43 ± 0.04, m = 0.64 ± 0.03, h = 0.53 ± 0.14, c = -0.01 ± 0.04, observed for 4 in the 22 solvents indicate a slightly higher need for nucleophilic solvation (when compared to 3) due to the destabilizing effect caused by the presence of a chlorine atom in the para position. This destabilization also impacts the amount of charge delocalization into the ring resulting in a lower h value. The destabilizing effect is amplified in 5 due to the existence of a more powerful inductive effect due to the presence of the electron-withdrawing nitro-group at the para position. The efficiency of transmission of the destabilizing electronic effects in 5 is made possible due to the complete coplanarity (as shown in the 3-D image, 5’) between the nitro group, the aromatic ring, the vinylic double bond and the carbonyl group. At the other end of the spectrum, it was shown [49] that the observed specific rate order of kp-nitrophenyl chloroformate > kp-nitrobenzyl chloroformate is due in part to the p-nitrobenzyl group twisting out of the plane with its ether oxygen and therefore being able to exert only a fraction of its inductive ability.

In the 22 solvents for the solvolyses of 5, application of equation 2 yields, l = 0.61 ± 0.06, m = 0.49 ± 0.04, c = 0.07 ± 0.06, R = 0.941, and F-test = 73, and application of equation 4 leads to l = 0.74 ± 0.07, m = 0.56 ± 0.04, h = 0.56 ± 0.20 (0.01 probability of statistical insignificance), c = -0.08 ± 0.05, R = 0.959, and F-test = 68. Such large l values have been observed in the unimolecular solvolysis of other structurally diverse acid chlorides [2, 48] and are indicative of the need for appreciable solvation of the developing carbocation plus a more facile approach of the solvent to an initially sp2-carbon than to an initially sp3-carbon.

3. Conclusions

In the present study we demonstrate that dispersions observed in Grunwald-Winstein correlations of the unimolecular solvolyses of substrates containing an adjacent π-electrons can be very well corrected by addition of an hI term. For the cinnamyl and cinnamoyl halides studied, a stepwise ionization mechanism is proposed to be operating with the need for nucleophilic solvation of a resonance stabilized carbocation. The h values of ~1.00 in cinnamyl chloride (1), cinnamyl bromide (2), and cinnamoyl (3) chloride, is also consistent with one aromatic ring easily entering into conjugation with the developing resonance stabilized transition state. In cinnamoyl chlorides, electron withdrawing inductive effects (p-chloro and p-nitro substituents) decrease the charge delocalized into the ring (lower h value) and increase the need for nucleophilic solvation of the carbocation (higher l value).

4. Experimental Section

The cinnamyl chloride was purchased from the Sigma-Aldrich chemical company and was used as received. Solvents were purified and the kinetic runs carried out as described previously [42]. A substrate concentration of approximately 0.005 M in a variety of solvents was employed. The specific rates and associated standard deviations, as presented in Table 1, are obtained by averaging all of the values from, at least, duplicate runs. Multiple regression analyses were carried out using the Excel 2007 package from the Microsoft Corporation, and the 3D-views presented in Figure 3 for three of the five molecules used in this study were computed using the KnowItAll® Informatics System, ADME/Tox Edition, from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Philadelphia, PA.

FIGURE 2.

Molecular structures for cinnamyl chloride (1), cinnamyl bromide (2), cinnamoyl chloride (3), p-chlorocinnamoyl chloride (4), and p-nitrocinnamoyl chloride (5).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant number 2 P2O RR016472-10 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence (INBRE) grant to the state of Delaware was obtained under the leadership of the University of Delaware, and the authors sincerely appreciate their efforts. Additionally, A.M.D. acknowledges the receipt of a Tuition Scholarship from the NASA Grant NNG05GO92H Delaware Space Grant College and Fellowship Program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

References and notes

Anthony M. Darrington a Wesley College Biological Chemistry major completed this undergraduate project as part of the Senior Research Capstone Experience. He received an INBRE supported Undergraduate Research Assistantship in the Directed Research Program in Chemistry at Wesley, and an Undergraduate Tuition Scholarship through the NASA funded Delaware Space Grant Consortium program at the University of Delaware. In April 2010, he received the Undergraduate Student Award from the American Chemical Society Division of Environmental Chemistry in recognition of his success in the Wesley College directed research program in chemistry.

- 1.Grunwald E, Winstein S. The correlation of solvolysis rates. J Am Chem Soc. 1948;70:846–854. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kevill DN, D’Souza MJ. Sixty years of the Grunwald-Winstein equation: development and recent applications. J Chem Res. 2008:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schleyer PvR, Nicholas RD. The reactivity of bridgehead compounds of adamantane. J Am Chem Soc. 1961;83:2700–2707. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentley TW, Schleyer PvR. Medium effects on the rates and mechanisms of solvolytic reactions. Adv Phys Org Chem. 1977;14:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bentley TW, Carter GE. The SN2-SN1 spectrum. 4. Mechanism for solvolyses of tert-butyl chloride: A revised Y scale of solvent ionizing power based on solvolyses of 1-adamantyl chloride. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:5741–5747. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentley TW, Llewellyn G. Yx scales of solvent ionizing power. Prog Phys Org Chem. 1990;17:121–158. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winstein S, Grunwald E, Jones HW. The correlation of solvolyses rates and the classification of solvolysis reactions into mechanistic categories. J Am Chem Soc. 1951;73:2700–2707. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minegishi S, Kobayashi S, Mayr H. Solvent nucleophilicity. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5174–5181. doi: 10.1021/ja031828z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kevill DN. Development and uses of scales of solvent nucleophilicity. In: Charton M, editor. Advances in quantitative structure-property relationships. Vol. 1. JAI Press; Greenwich, CT: 1996. pp. 81–115. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kevill DN, Anderson SW. An improved scale of solvent nucleophilicity based on the solvolysis of the S-methyldibenzothiophenium ion. J Org Chem. 1991;56:1845–1850. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bentley TW, Koo IS, Norman SJ. Distinguishing between solvation effects and mechanistic changes. Effects due to the differences in solvation of aromatic rings and alkyl groups. J Org Chem. 1991;56:1604–1609. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu K-T. Nucleophilic solvent intervention in benzylic solvolyses. The use of YBnX scales in Grunwald-Winstein type correlation analysis. J Chin Chem Soc. 1995;42:607–615. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu K–T, Sheu H–C. Solvolysis of 2-aryl-2-chloroadamantanes. A new Y scale for benzylic chlorides. J Org Chem. 1991;56:3021–3025. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu K–T, Lin Y–S, Duann Y–F. Solvent effects on the solvolysis of some secondary tosylates. Applications of YBnOTs and YxBnOTs scales to mechanistic studies. J Phys Org Chem. 2002;15:750–757. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kevill DN, D’Souza MJ. Concerning the development of scales of solvent ionizing power based on solvolyses of benzylic substrates. J Phys Org Chem. 1992;5:287–294. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujio M, Saeki Y, Nakamoto K, Yatsugi K, Goto N, Kim SH, Tsuji Y, Rappoport Z, Tsuno Y. Solvent effects on anchimerically assisted solvolyses. II. Solvent effects in solvolyses of threo-2-aryl-1-methylpropyl-p-toluenesulfonates. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1995;68:2603–2617. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kevill DN, Ismail NHJ, D’Souza MJ. Solvolysis of the (p-methoxybenzyl) dimethylsulfonium ion. Development and use of a scale to correct for dispersion in Grunwald-Winstein plots. J Org Chem. 1994;59:6303–6312. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reis MC, Elvas-Leitão R, Martins F. The influence of carbon-carbon multiple bonds on the solvolyses of tertiary alkyl halides: A Grunwald-Winstein analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2008;9:1704–1716. doi: 10.3390/ijms9091704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kevill DN, D’Souza MJ. Use of the simple and extended Grunwald-Winstein equations in the correlation of the rates of solvolysis of highly hindered tertiary alkyl derivatives. Cur Org Chem. 2010;14:0000–0000. doi: 10.2174/138527210791130505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goossens A, Huygens S, Stoskute L, Lepoittevin J–P. Primary sensitization to cinnamyl chloride in an operator of a pharmaceutical company. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:364–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2006.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayami J–I, Tanaka N, Kaji A. SN2 Reactions in dipolar aprotic solvents. III. Chlorine isotopic exchange reactions of cinnamyl chlorides and 3-aryl-2-propynyl chlorides. Effect of the unsaturated group adjacent to the reaction center. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1973;46:954–959. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayami J–I, Hihara N, Tanaka N, Kaji A. SN2 reactions in dipolar aprotic solvents. VII. Kinetic and equilibrium secondary α-deuterium isotope effects in chlorine isotopic exchange reactions of substituted chloromethanes in acetonitrile. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1979;52:831–835. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koo IS, An SK, Yang K, Lee I, Bentley TW. Correlation of the rates of solvolyses of cinnamyl chloride. J Phys Org Chem. 2002;15:758–764. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koo IS, Cho JM, An SK, Yang K, Lee JP, Lee I. Correlation of the rates of solvolysis of cinnamyl bromide. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2003;24:431–436. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bentley TW, Llewellyn G, Ryu ZH. Solvolytic reactions in fluorinated alcohols. Role of nucleophilic and other solvation effects. J Org Chem. 1998;63:4654–4659. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown DK, Dean JL, Lopez WX, Chang J. Electrochemical reduction of cinnamyl bromide at carbon cathodes in acetonitrile: A further mechanistic study. J Electrochem Soc. 2009;156:F123–F127. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marona H, Szkaradek N, Karczewska E, Trojanowska D, Budak A, Bober P, Przepiórka W, Cegla M, Szneler E. Antifungal and antibacterial activity of the newly synthesized 2-xanthone derivatives. Archiv der Pharmazie. 2008;342:9–18. doi: 10.1002/ardp.200800089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sneff-Ribeiro A, Echevarria A, Silva EF, Franco CRC, Viega SS, Olivera MBM. Cytotoxic effect of a new 1,3,4-thiadiazolium mesoionic compound (MI-D) on cell lines of human melanoma. British J Cancer. 2004;91:297–304. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koo IS, Kim J–S, An SK, Yang K, Lee I. Kinetic studies on solvolyses of substituted cinnamoyl chlorides in alcohol-water mixtures. J Korean Chem Soc. 1999;43:527–534. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kevill DN, D’Souza MJ. Concerning the extent of nucleophilic participation in the solvolyses of p-methoxybenzyl halides. J Chem Res (S) 1999:336–337. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kevill DN, D’Souza MJ. Correlation of the rates of solvolysis of benzoyl chloride and derivatives using extended forms of the Grunwald-Winstein equation. J Phys Org Chem. 2002;15:881–888. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JD, Han G, Jeong LS, Park H–J, Zee OP, Jung YH. Study of the stability of carbocations by chlorosulfonyl iocyanate reactions with ethers. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:4395–4402. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koo IS, Yang K, Kang DH, Park HJ, Kang K, Lee I. Transition-state variation in the solvolyses of phenyl chlorothionoformate in alcohol-water mixtures. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 1999;20:577–580. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kevill DN, Koyoshi F, D’Souza MJ. Correlations of the specific rates of solvolysis of carbamoyl chlorides, chloroformates, chlorothionoformates, and chlorodithioformates revisited. Int J Mol Sci. 2007;8:346–362. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bentley TW. Structural effects on the solvolytic reactivity of carboxylic and sulfonic acid chlorides. Comparisons with gas-phase data for cation formation. J Org Chem. 2008;73:6251–6257. doi: 10.1021/jo800841g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Artico M, Di Santo R, Costi R, Novollino E, Greco G, Massa S, Tramontano E, Marongiu M, De Montis A, La Colla P. Geometrically and conformationally restrained cinnamoyl compounds as inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase: Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular modeling. J Med Chem. 2008;41:3948–3960. doi: 10.1021/jm9707232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richard JP, Jencks WP. Reactions of substituted 1-phenylethyl carbocations with alcohols and other nucleophilic reagents. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:1373–1383. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richard JP, Toteva MM, Amyes TL. What is the stabilizing interaction with nucleophilic solventsin the transition state for solvolysis of tertiary derivatives: Nucleophilic solvent participation or nucleophilic solvation? Org Lett. 2001;3:2225–2228. doi: 10.1021/ol016103j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McManus SP, Crutcher T, Naumann RW, Tate KL, Zutaut SE, Katritzky AR, Kevill DN. Selectivity in the solvolysis in binary solvents of 1-adamantyl derivatives bearing leaving groups that depart as neutral molecules. J Org Chem. 1988;53:4401–4403. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kevill DN, Anderson SW. Essentially solvent-independent rates of solvolysis of the 1-adamantyldimethylsulfonium ion. Implications regarding nucleophilic solvent assistance in solvolyses of tert-butyl derivatives and the NKL solvent nucleophilicty scale. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:1579–1585. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bentley TW. Nucleophilicites of aqueous, alcoholic, and acidic media. Advances in Chemistry. 1987;15:255–268. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kevill DN, Ryu ZH, Niedermeyer M, Koyoshi F, D’Souza MJ. Rate and product studies in the solvolyses of methanesulfonic anhydride and a comparison with methanesulfonyl chloride solvolyses. J Phys Org Chem. 2007;20:431–438. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kevill DN, Miller B. Application of the NT solvent nucleophilicity scale to attack at phosphorus: Solvolyses of N, N, N’, N’-tetramethyldiamidophosphorochloridate. J Org Chem. 2002;67:7399–7406. doi: 10.1021/jo020467n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kyong JB, Ryu SH, Kevill DN. Rate and product studies of solvolyses of benzyl fluoroformate. Int J Mol Sci. 2006;7:186–196. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koh HJ, Kang SJ, Kevill DN. Reaction mechanism studies of solvolytic displacement of chlorine from phosphorus. Phosphorus, Sulfur, and Silicon. 2008;183:364–368. [Google Scholar]

- 46.D’Souza MJ, Yaakoubd L, Mlynarski SL, Kevill DN. Concerted solvent processes for common sulfonyl chloride precursors used in the synthesis of sulfonamide-based drugs. Int J Mol Sci. 2008;9:914–925. doi: 10.3390/ijms9050914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seong MH, Kyong JB, Lee YH, Kevill DN. Correlation of the specific rates of solvolysis of ethyl fluoroformate using the extended Grunwald-Winstein equation. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10:929–941. doi: 10.3390/ijms10030929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryu ZH, Park B–C, Kevill DN, D’Souza MJ. Correlation of the rates of solvolysis of acetyl chloride and α-substituted derivatives. Can J Chem. 2008;86:359–367. [Google Scholar]

- 49.D’Souza MJ, Shuman KE, Carter SE, Kevill DN. Extended Grunwald-Einstein analysis – LFER used to gauge solvent effects in p-nitrophenyl chloroformate solvolysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2008;9:2231–2242. doi: 10.3390/ijms9112231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]