Fat embolism syndrome (FES) is a serious disorder occurring after trauma, orthopaedic surgeries and rarely in non-traumatic patients. Nearly all patients with bone fractures develop fat emboli, but they are usually asymptomatic. In this report we describe a case of FES which presented atypically.

CASE REPORT

A 25-year old, ASA physical status 1, lady referred to hospital following a road accident that occurred 24 hours back, had compound fracture of left femur, tibia and fibula. Significant in history was transient loss of consciousness (10 min.) with no history of ENT bleed, seizures or vomiting. She was conscious, oriented and haemodynamically stable. Head, thoracic and intra-abdominal injury were ruled out. She was scheduled for interlocking intramedullary nailing of left femur and tibia under combined spinal epidural anaesthesia. While advancing the epidural catheter in L2-L3 space, duramater was accidentally punctured. Hence epidural space was again identified at L1-L2 interspace. Test dose (3 ml of 2% lignocaine + 5 μgml-1 adrenaline) was negative. Subarachnoid block achieved with 2.8 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine at L3-L4 interspace attained T10 level. Morphine 3 mg was injected epidurally to supplement analgesia. About an hour into the procedure, pulse oximeter was not picking the signals and intermittently showed values of 98-100%. The patient's peripheries were cold. She was awake and comfortable during reaming of the bone. Surgery lasted for 4 hours, resulting in 300mL of blood loss (adequately replaced). The patient was haemodynamically stable throughout and seemed sedated during the last 2 hours (drowsy but arousable).

As she was wheeled out of the OT, she suddenly became unresponsive to verbal commands and pain. Her respiratory rate was 30/min, pulse rate 130/min and arterial pressure 110/70 mmHg. Immediately her trachea was intubated and was shifted to ICU. Her vital parameters in ICU were - heart rate 128/min, arterial pressure 100/60 mmHg, SpO2 96% with 100% O2 , GCS E3 VT M4 , pupils equal and reacting to light and afebrile. On auscultation bilateral crepitations were heard. ABG showed PaO2 86.8 mmHg on FiO 1. Frothy secretions were noted in the tracheal tube.

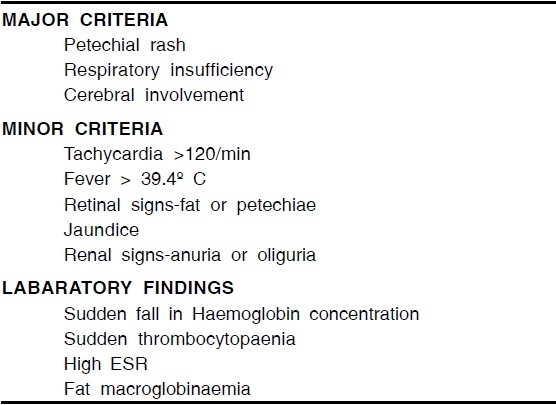

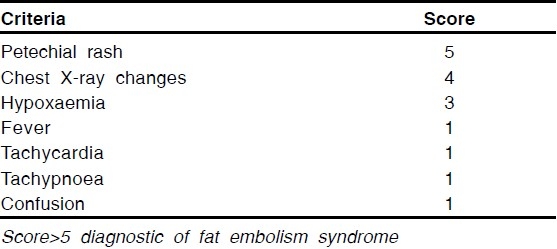

Chest X-ray revealed bilateral infiltrates suggestive of pulmonary oedema. Bedside echocardiography was normal. Based on Gurd and Wilson's criteria3 (Table 1) 2 major criteria (respiratory insufficiency, cerebral involvement), 2 minor criteria (tachycardia, oliguria) and 3 laboratory findings (sudden fall in haemoglobin concentration from 10.4 gdl-1 to 8.4 gdl-1, sudden thrombocytopaenia from 1,95,000 mm3 to 81000 mm3 and presence of fat macroglobinaemia) a diagnosis of FES was made. Even by Schonfeld's scoring system4 (Table 2) she had a score of 9 (chest x-ray changes, hypoxaemia, tachycardia, tachypnoea).

Table 1.

Gurd and Wilson criteria to diagnose fat embolism syndrome3

Table 2.

Schonfeld's scoring to diagnose fat embolism syndrome4

Patient regained complete consciousness after 4 hours. With supportive treatment (mechanical ventilation with PEEP and diuretics) she showed improvement. Ventilatory support was weaned over next 4 days and trachea extubated. During this period, her PaO2/FiO2 ratio improved from 80 to 400. Subsequent recovery was uneventful.

DISCUSSION

We encountered an atypical presentation of fat embolism syndrome in the form of sudden loss of consciousness immediately after the surgery.

Only few patients develop features of various organ system dysfunction due to either mechanical obstruction of capillaries by fat emboli or hydrolysis of fat to fatty acids. After an asymptomatic period of 24 to 72 hours a triad of lung, brain and skin involvement develops. This symptom complex is called FES.1 The incidence reported is up to 30%, but many mild cases recover unnoticed.2 Diagnosis of FES is clinical with nonspecific, insensitive diagnostic test results. Gurd and Wilson proposed the most widely accepted guidelines for the diagnosis of FES, which require at least one sign from the major and at least four signs from the minor criteria and at least one laboratory finding (Table 1).3 Gurd and Wilson's criteria have been criticized for not specifically assessing oxygenation with ABG. Schonfeld's scoring system incorporated this (Table 2).4 A cumulative score > 5 is required for diagnosis. Our diagnosis of FES was in line with these criteria.

In this case, sudden loss of consciousness was noticed in the immediate postoperative period. Though the patient was drowsy during the intraoperative period she was arousable. We did not attribute this drowsiness to FES and considered it as sedative action of epidural morphine.

Cerebral changes are seen in 86% of cases ranging from headache and confusion, to stupor, rigidity, convulsions and coma.1 It has been observed that postoperatively, all patients having FES developed neurological signs and hypoxaemia.5 Unfortunately the saturation probe was not functioning properly in the intraoperative period (again erroneously attributed to cold extremities) thus missing another early sign.

Our differential diagnoses were cerebrovascular accident and inadvertent intrathecal injection of morphine following prior accidental dural puncture. Since she was not a known hypertensive, there were no haemodynamic swings intraoperatively and focal neurological signs were absent we excluded cerebrovascular accident. The possibility of 3 mg morphine entering into the subarachnoid space through the dural puncture was ruled out as there was no accompanying respiratory depression.

Since FES is diagnosed by non-specific diagnostic tests, non-universal criteria, and is mainly a diagnosis of exclusion, a high degree of suspicion is required.

Early warning signs of CNS could be masked by sedatives used intraoperatively and can manifest as sudden loss of consciousness in the ostoperative period.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaikh N, Parchani A, Bhat V, Kattren MA. Fat embolism syndrome: Clinical and imaging considerations: Case report and review of literature. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2008;12:32–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.40948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fabian TC, Hoots AV, Stanford DS, Patterson CR, Mangiante EC. Fat embolism syndrome, prospective evaluation in 92 fractured patients. Crit Care Med. 1990;18:42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurd AR, Wilson RI. The fat embolism syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1974;56 B:408–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schonfeld SA, Polysangsong Y, DiLisio R, et al. Fat embolism prophylaxis with corticosteroids. A prospective study in high-risk patients. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:438–43. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-99-4-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kathryn Jenkins, Frances Chung, Richard Wennberg, Etchells Edward E, Davey Rod. Etchells, Rod Davey.Fat embolism syndrome and elective knee arthroplasty. Can J Anesth. 2002;49:19–24. doi: 10.1007/BF03020414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]