Abstract

Background:

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is commonly seen after laparoscopic surgery. In this randomized double blind prospective clinical study, we investigated and compared the efficacy of palonosetron and granisetron to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Patients & Methods:

Sixty female patients (18-65 yrs of age) undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy were randomly allocated one of the two groups containing 30 patients each. Group P received palonosetron 75 μg intravenously as a bolus before induction of anaesthesia. Group G received granisetron 2.5 mg intravenously as a bolus before induction.

Results:

The incidence of a complete response (no PONV, no rescue medication) during 0-3 hour in the postoperative period was 86.6% with granisetron and 90% with palonosetron, the incidence during 3-24 hour postoperatively was 83.3% with granisetron and 90% with palonosetron. During 24-48 hour, the incidence was 66.6% and 90% respectively (p<0.05). The incidence of adverse effects were statistically insignificant between the groups.

Conclusion:

Prophylactic therapy with palonosetron is more effective than granisetron for long term prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Keywords: Palonosetron, Granisetron, Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV), Laparoscopic surgery

Post operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) are distressing symptoms that commonly occur after laparoscopic surgery performed under general anaesthesia1. Vomiting may cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, disruption of surgical repair and increase the perception of pain2. A number of pharmacological agents (antihistamines, butyro-phenones, dopamine receptor antagonists) have been tried for the prevention and treatment of PONV but undesirable adverse effects such as excessive sedation, hypertension, dry mouth, dysphoria, hallucinations and extra pyramidal symptoms have been noted3. 5-hydroxytryptamine type3(5HT3) receptor antagonists are devoid of such side effects and highly effective in prevention and treatment of PONV.

Granisetron is a highly selective and potent 5-HT3 receptor antagonist4. It acts specifically at 5-HT3 receptors on the vagal afferent nerves of the gut. Granisetron produces irreversible block of the 5-HT3 receptors and it may account for the long duration of this drug5,6.

Palonosetron is a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist used for preventing chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting. This unique 5-HT3 receptor antagonist has a greater binding affinity and longer half-life than older 5-HT3 antagonists like ondansetron. Recent receptor binding studies suggest that palonosetron is further differentiated from other 5-HT3 by interacting with 5-HT3 receptors in an allosteric, positively cooperative manner at sites different from those that bind with ondansetron and granisetron7. In addition, this sort of receptor interaction may be associated with long lasting effects on receptor ligand binding and functional responses to serotonin8.

We designed this prospective randomized double blind trial to assess and compare the antiemetic efficacy of granisetron and palonosetron to prevent PONV in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

PATIENTS & METHODS

The study protocol was approved by the institution ethical committee and informed consent was obtained from every patient. Sixty ASA I-II female patients, aged 18-65 years, undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy were randomly assigned to one of the two groups, containing thirty patients each. Patients who had gastrointestinal disease, were smokers, had history of motion sickness and/ or PONV, were pregnant or menstruating and those who had taken antiemetic medication within last 24 hours were excluded from the study.

Identical syringes containing study medications (2.5 ml) were prepared by the personal who were blinded to the computer generated randomization schedule. Patients were randomly allocated into two groups (n=30 each) to receive one of the following regimens: palonosetron 75μg in 2.5 ml (0.9% saline was added to make the desired volume) [group P] or granisetron 2.5 mg in 2.5 ml[group G]. The study medication were administered immediately before the induction of anaesthesia.

All patients were kept fasting after midnight and received midazolam 7.5 mg orally as premedication. On the operation table, routine monitoring (ECG, pulse oximetry, NIBP) were started and baseline vital parameters like heart rate(HR), blood pressure(systolic, diastolic and mean) and arterial oxygen saturation(SpO2) were recorded. An intravenous line was secured.

After preoxygenation for 3 minutes, induction of anaesthesia was done by fentanyl 2μg kg-1 and thiopental 5mg kg-1. Patients were intubated with appropriate size endotracheal tube after muscle relaxation with vecuronium bromide in a dose of 0.08mg kg-1. Anaesthesia was maintained with 33% oxygen in nitrous oxide and sevoflurane 2%. Muscle relaxation was maintained by intermittent bolus doses of vecuronium bromide. The patients were mechanically ventilated to keep EtCO2 between 35-40 mm Hg. A nasogastric tube was inserted to make the stomach empty of air and other contents. For laparoscopic surgical procedure, peritoneal cavity was insufflated with carbon dioxide to keep intra abdominal pressure <14 mmHg. At the end of surgical procedure, residual neuromuscular block was adequately reversed using intravenous glycopyrrolate and neostigmine and subsequently extubated. Before tracheal extubation, the nasogastric tube was suctioned and removed. For postoperative analgesia, diclofenac transdermal patch was applied on body surface. All patients were observed postoperatively by resident doctors who were unaware of the study drug. Patients were transferred to postanaesthesia care unit and blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation were monitored. All episodes of PONV (nausea, retching and vomiting) were recorded for 0-3 hour in postanaesthesia care unit and from 3-48 hour in postoperative ward.

Nausea was defined as unpleasant sensation associated with awareness of the urge to vomit. Retching was defined as the laboured, spastic, rhythmic contraction of the respiratory muscles without the expulsion of gastric contents. Vomiting was defined as the forceful expulsion of gastric contents from mouth. Complete response (free from emesis) was defined as no PONV and no need for any rescue medication. If there were two or more episodes of PONV during first 48 hours, rescue antiemetic (metoclopramide10 mg i.v.) was given.

Data were analyzed using computer statistical software system Graph Pad Instat Version 3.05 (Graph Pad software, San Diego, CA) and are presented in a tabulated manner. Comparisons between groups were performed by using the Kruskal Wallis one way ANOVA by ranks or Fisher's exact test for small sample with a 5% risk or Mann - Whitney - Wilcoxon tests when normality tests failed or Chi-square test, as appropriate. The results were expressed in mean±SD and number (%).

RESULTS

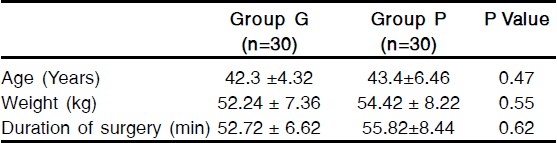

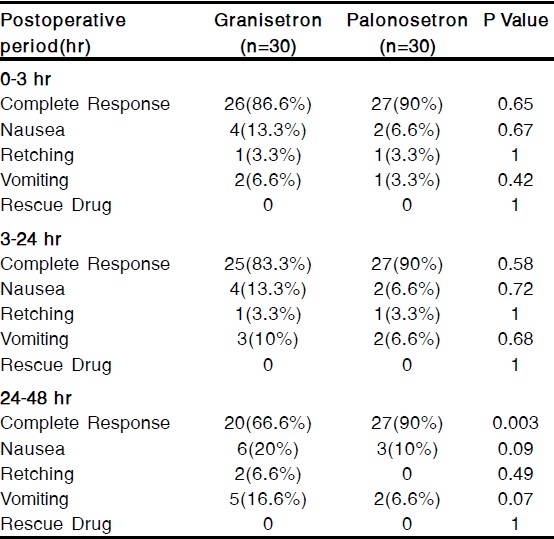

The groups were comparable with respect to age, weight and duration of surgery [Table 1]. The incidence of a complete response (no PONV, no rescue medication) during 0-3 hour in the postoperative period was 86.6% with granisetron and 90% with palonosetron, the incidence during 3-24 hour postoperatively was 83.3% with granisetron and 90% with palonosetron. During 24-48 hour, the incidence was 66.6% and 90% respectively [Table 2]. Thus a complete response during 24-48 hour in the postoperative period was significantly more patients who had received palonosetron than in those who had received granisetron (p<0.05) [Table 2].

Table 1.

Patient's characteristics and duration of surgery (Mean ± SD)

Table 2.

Incidence of Postoperative Nausea & Vomiting(PONV)

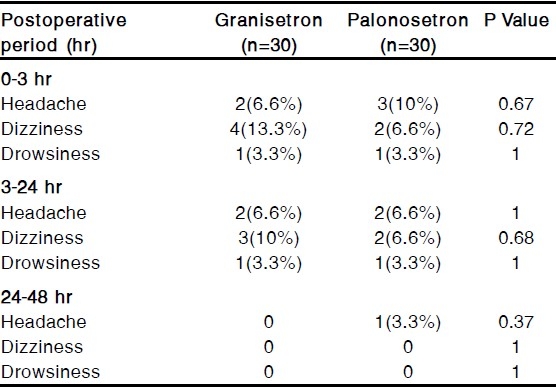

The commonly observed adverse effects were headache, dizziness and drowsiness but those were not clinically serious or significant. The incidence of adverse effects were statistically insignificant between the groups [Table 3].

Table 3.

Incidence of Adverse Effects

DISCUSSION

Postoperative period is associated with variable incidence of nausea and vomiting depending on the duration of surgery, the type of anaesthetic agents used (dose, inhalational drugs, opioids), smoking habit etc9. 5-HT3 receptor stimulation is the primary event in the initiation of vomiting reflex10. These receptors are situated on the nerve terminal of the vagus nerve in the periphery and centrally on the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) of the area postrema3. Anaesthetic agents initiate the vomiting reflex by stimulating the central 5-HT3 receptors on the CTZ and also by releasing serotonin from the enterochromaffin cells of the small intestine and subsequent stimulation of 5-HT3 receptors on vagus nerve afferent fibres3.

The incidence of PONV after laparoscopic surgery is high(40-75%). The etiology of PONV after laparoscopic surgery is complex and is dependent on a variety of factors including age, obesity, a history of previous PONV, surgical procedure, anesthetic technique, and post operative pain11. In this study, however, both the groups were comparable with respect to patient demographics, types and duration of surgery and anesthesia and analgesics used postoperatively. Therefore the difference in a complete response (no PONV, no rescue medication) between the groups can be attributed to the study drug.

Granisetron is effective for the treatment of emesis induced by cancer chemotherapy12. The precise mechanism of granisetron for the prevention of PONV remains unclear, but it has been suggested that granisetron may act on sites containing 5-HT3 receptors with demonstrated antiemetic effects13. Palonosetron is a unique 5-HT3 receptor anatagonist approved for the prevention of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting. It is a novel 5-HT3 receptor antagonist with a greater binding affinity and longer biological half-life than older 5-HT3 receptor antagonists7. The exact mechanism of palonosetron in the prevention of PONV is unknown but palonosetron may act on the area postrema which contain a number of 5-HT3 receptors8. Therefore, the possible mechanism of this antiemetic for preventing PONV is similar to that of granisetron.

The effective dose of granisetron is 40-80μg kg-1 for the treatment of cancer chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting14. The dose of granisetron 2.5 mg (approximately 45μg kg-1) selected for this study was within its effective dose range (40-80μg kg-1). However, the dose of palonosetron to be used for the prevention of PONV is not established but was extrapolated from the dose used in the clinical trials15,16. Kovac LA and Colleagues16 demonstrated that palonosetron 75μg is the more effective dose for the prevention of PONV after major gynecological and laparoscopic surgery than 25μg and 50μg.16

Our study demonstrate that the antiemetic efficacy of palonosetron is similar to that of granisetron for preventing PONV during the first 24 hours (0-24 hours) after laparoscopic surgery and that palonosetron is more effective than granisetron for getting a complete response (no PONV, no rescue medication) for 24-48 hours. This suggests that palonosetron has an antiemetic effect which lasts longer than granisetron. The exact reason for the difference in effectiveness between granisetron and palonosetron is not known but may be related to the half lives (granistron 8-9 hrs versus palonosetron 40 hrs) and/or the binding affinities of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (palonosetron interacts with 5-HT3 receptors in an allosteric, positive cooperative manner at sites different from that bind with granisetron )7,8.

We did not include a control group receiving placebo in our study. Aspinall and Goodman17 have suggested that if active drugs are available, placebo controlled trials may be unethical because PONV are very much distressing after laparoscopic surgery17.

Adverse effects with a single therapeutic dose of granisetron or palonosetron were not clinically serious16,18 and there were no significant differences in the incidence of headache, dizziness and drowsiness between the groups. Thus both palonosetron and granisetron are devoid of clinically important side effects.

In conclusion prophylactic therapy with palonosetron is more effective than prophylactic therapy with granisetron for the long term prevention of PONV after laparoscopic surgery.

Author disclosures: Authors have no conflict of interest or financial considerations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Madej T, Simpsom K. Comparison of the use of domperidone, droperidol and metoclopramide in the prevention of nausea and vomiting following gynecological surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1986;58:879–83. doi: 10.1093/bja/58.8.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jellish WS, Leonetti J P, Sawicki K, et al. Morphine/ ondansetron PCA for postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting after skull base surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watcha MF, White PF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting: its etiology, treatment and prevention. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:162–84. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199207000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blower PR. The role of specific 5-HT3 receptor antagonigm in the control of cytostatic drug-induced emesis. Euro J Cancer. 1990;26(suppl. 1):s8–s11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newberry NR, Watkins CJ, Sprosen TS, Blackburn TP, Grahame-Smith DG, Leslie RA. BRL 46470 potently antagonizes neural responses activated by 5-HT 3 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:729–735. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90180-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliott P, Seemungal BM, Wallis DI. Antagonism of the effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine on the rabbit isolated vagus nerve by BRL 43694 and metoclopramide. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Archives of Pharmacology. 1990;341:503–09. doi: 10.1007/BF00171729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rojas C, Stathis M, Thomas A, Massuda E, Alt J, Zhang J, Rubenstein E, Sebastianis S, Canloreggi S, Snyder SH, Slusher B. Palonosetron exhibits unique molecular interactions with the 5-HT 3 receptor .Anesth Analg. 2008;107:469–78. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318172fa74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gralla R, Lichinitser M, Vander Vegt S, Sleeboom H, Mezger J, Peschel C, Tonini G, Libianca R, Macciocchi A, Aapro M. Palonosetron improves prevention of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: results of a double-blind randomized phase 3 trial comparing single doses of palonosetron with ondansetron. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1570, 7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lerman J. Surgical and patient factors involved in postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69:245–325. doi: 10.1093/bja/69.supplement_1.24s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bunce KT, Tyers MB. The role of 5-HT in postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69(suppl. 1):S60–S62. doi: 10.1093/bja/69.supplement_1.60s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janknegt R, et al. Clinical efficacy of antiemetics following surgery. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:1059–68. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bermudez J, Boyle EA, Minter WD, Sanger GJ. The antiemetic potential of the 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 receptor antagonist BR 43694. Br J Cancer. 1988;58:644–50. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1988.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmichel J, Cantwell BMJ, Edwards CM, et al. A pharmacokinetic study of granisetron ( BRI 43694A), a selective 5-HT 3 receptor antagonist : correlation of antiemetic response. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1989;24:45–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00254104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furue H, Oota K, Taguchi T, Niitani H. Clinical evaluation of granisetron against nausea and vomiting induced by anticancer drugs : optimal dose finding study. J Clin Ther Med. 1990;6:49–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Candiotti KA, Kovac AL, Melson TI, Clerici G, Gan TJ. A randomized double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of three different doses of palono-setron versus placebo for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:445–51. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817b5ebb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovac AL, Eberhart L, Kotarski J, Clerici G, Apfel C. A randomized double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of three different doses of palonosetron versus placebo for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting over a 72 hour period. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:439–44. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817abcd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aspinall RL, Goodman NW. Denial of effective treatment and poor quality of clinical information in placebo controlled trials of ondansetron for postoperative nausea and vomiting: a review of published trials. BMJ. 1995;311:844–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7009.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yarker YE, Mactavish D. Granisetron: an update of its therapeutic use in nausea and vomiting induced by antineoplasmic therapy. Drugs. 1994;48:761–93. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199448050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]