Abstract

Background

Prevention of childhood obesity is a public health priority. Parents influence a child’s weight by modeling healthy behaviors, controlling food availability and activity opportunities, and appropriate feeding practices. Thus interventions should target education and behavioral change in the parent, and positive, mutually reinforcing behaviors within the family.

Methods

This paper presents the design, rationale and baseline characteristics of Kids and Adults Now! – Defeat Obesity (KAN-DO), a randomized controlled behavioral intervention trial targeting weight maintenance in children of healthy weight, and weight reduction in overweight children. 400 children aged 2–5 and their overweight or obese mothers in the Triangle and Triad regions of North Carolina are randomized equally to control or the KAN-DO intervention, consisting of mailed family kits encouraging healthy lifestyle change. Eight (monthly) kits are supported by motivational counseling calls and a single group session. Mothers are targeted during a hypothesized “teachable moment” for health behavior change (the birth of a new baby), and intervention content addresses: parenting skills (emotional regulation, authoritative parenting), healthy eating, and physical activity.

Results

The 400 mother-child dyads randomized to trial are 75% white and 22% black; 19% have a household income of $30,000 or below. At baseline, 15% of children are overweight (85th–95th percentile for body mass index) and 9% are obese (≥95th percentile).

Conclusion

This intervention addresses childhood obesity prevention by using a family-based, synergistic approach, targeting at-risk children and their mothers during key transitional periods, and enhancing maternal self-regulation and responsive parenting as a foundation for health behavior change.

Keywords: Overweight, obesity, randomized controlled trial, parenting, children, postpartum period

BACKGROUND

Childhood obesity is a public health priority [1,2]. Treatment guidelines from Institute of Medicine [2] and the Department of Health and Human Services [3] recommend involving the family to create a home environment conducive to weight control. The presence of at least one overweight parent triples the likelihood that a child will be overweight, and at young ages is a stronger predictor of the child’s future obesity risk than the child’s own weight [4]. Parents can serve as powerful agents of change since they influence a child’s weight and weight-related behaviors through role modeling of healthy behaviors, controlling food availability and opportunities for physical activity, and engaging in appropriate feeding practices [5]. Furthermore, family-based interventions can improve diet and activity not only in the target child but also in adults living in the household [6–7].

The period between ages 2 and 5 is a critical developmental transition in which food and taste preferences are being established [8–9]. In households that routinely stock vegetables, fruits, and other healthy foods, children will develop preferences from a range of healthier options [10], and maternal role modeling of healthy lifestyle choices is positively associated with similar behaviors in children at this young age [11]. Children in this age group also have a natural tendency toward self-regulation of food intake, which can be undermined by parental insistence on larger portion sizes or encouragement to over-consume energy-dense foods [8,12]. Restrictive maternal feeding practices and the use of food to reinforce behavioral contingencies may also contribute to poor self-regulation and satiety responsiveness [13].

An intervention for childhood obesity that emphasizes parenting skills can provide mothers increased ability to implement behavioral changes in the home [3]. Features of the home environment associated with decreased health-related risk behaviors in adolescents, including disordered eating, include parenting factors such as consistent family routines and a firm and supportive parenting approach [14–16]. Instruction in a firm, supportive parenting style has yet to be examined in interventions for childhood obesity.

While parents are a necessary target for interventions in this age group, if the parent is not ready for change the intervention is more likely to fail [17–18]. The transition from pregnancy to postpartum could significantly impact three psychological domains suggested to characterize a “teachable moment”, or a cuing event that may affect a mother’s readiness to change behavior. The teachable moment heuristic posits that health events and life transitions that jointly increase perceptions of vulnerability to health risks, prompt emotional responses, and impact self image may offer a powerful motivational context for promoting behavior change [19]. The teachable moment concept is appealing because timing formal interventions to coincide with these naturally occurring events might increase the efficacy of the type of interventions best suited for widespread dissemination. Although it targeted only the overweight/obese postpartum mothers, and not their children, our previous behavioral intervention trial “Active Mothers Postpartum” also utilized the teachable moment concept [20].

The objective of this paper is to present the design, rationale, and key baseline participant characteristics of Kids and Adults Now! Defeat Obesity (KAN-DO), a family-based behavioral intervention for the prevention of childhood obesity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

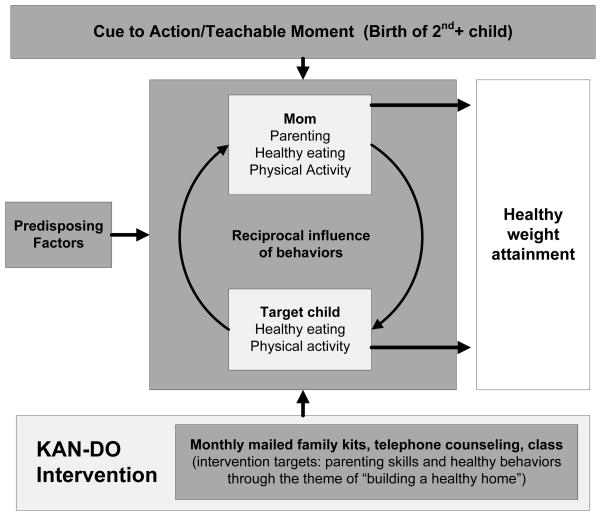

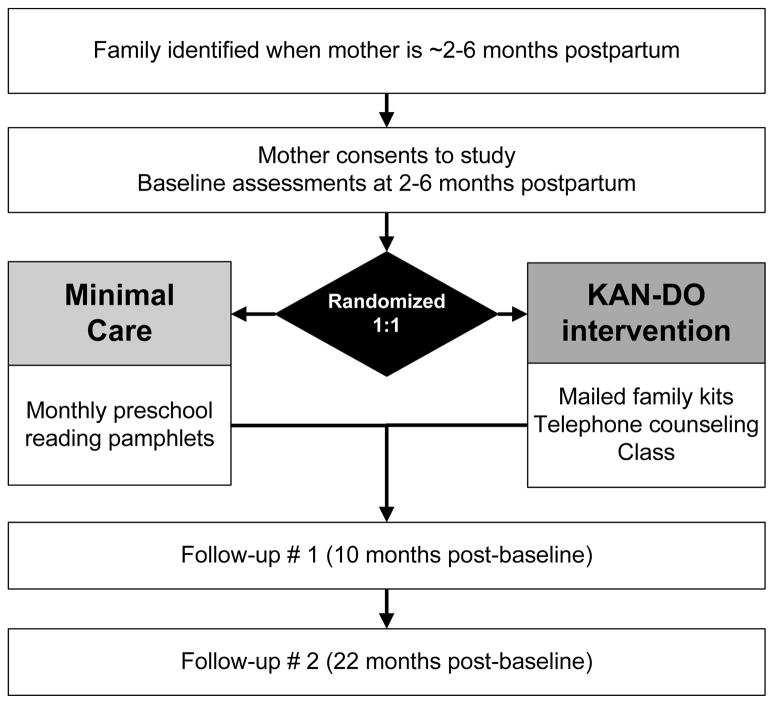

KAN-DO is a randomized controlled trial designed to evaluate the effect of a family-based parenting intervention to promote healthy weight attainment in preschool children (weight maintenance among those of normal weight, relative weight reduction among those overweight) through improved dietary habits, increased physical activity, and decreased sedentary behaviors. Secondary aims of the study relate to weight loss and improved weight-related behaviors in the mothers. Additional secondary aims relate to changes in the mother’s parenting skills, and the possible impact of teachable moment factors on intervention effects. The KAN-DO study design is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

KAN-DO study conceptual model

Conceptual overview

Figure 2 presents a graphical overview of the conceptual model for the study. At any given moment, the number and/or extent of demands on new mothers may exceed their capacities. If new behavior change strategies are to be successfully implemented in this period, interventions for health behavior change should first address mothers’ capacities to handle general life stressors. Our intervention sought to enhance self-efficacy for behavior change by addressing the mother’s self-regulatory capacities (her emotional regulation, sleep, and parenting practices) prior to addressing change in eating and activity behaviors. We hypothesized that by emphasizing process issues such as parenting style and the capacity to better understand and respond to their own emotional needs, we could provide mothers a strong foundation for addressing life stressors more generally, and subsequent changes in eating and activity would have greater likelihood for success.

Figure 2.

KAN-DO study design

In this way, we attempted to increase capacity to responsively parent by first teaching mothers to responsively “parent” themselves – i.e. they would be better at sensing their child’s sadness, hunger, etc. if they were better at sensing and responding to their own (a strategy consistent with advances in the nature of empathic attunement). Thus, self-efficacy for behavior change is enhanced by sequencing skills in a manner proposed to increase maternal competence. Parenting skills (e.g., an authoritative parenting style [14–15, 21–22], maternal feeding behavior [12–13]) are taught early in the intervention as a foundation for upcoming lifestyle change strategies.

We aim to capitalize on role modeling as a potent mechanism for behavior change [23–24]. The performance of health behaviors by both the mother and cartoon characters created for the intervention materials are used to reinforce adaptive changes in behavior. Repeatedly observing these characters (in program tools, in toy inducements, in program-related activities) is designed to cue participants to engage in healthy lifestyle behaviors in both mother and preschooler. Further, the mutual synergy of mother-child behavior change is proposed to potentiate intervention strategies, consistent with the tenets of social cognitive and behavioral theories [25].

Finally, intervening during a key transitional period is in accordance with motivational models of behavior change that capitalize on an individual’s readiness to initiate change efforts. According to motivational models, behavior change is more likely to occur when an individual is “ready, willing, and able” to undergo such changes [26]. “Ready” and “willing” relate to the perception by the individual that change is necessary and desired. By intervening during the postpartum period, in which a mother has a heightened awareness of both her and her children’s needs and may have a heightened level of affect and sense of health risks (a “teachable moment”), we seek to increase a mother’s motivation for and engagement in health-related behavioral change efforts [27]. By providing her with tools to regulate her emotions, parent effectively, and better understand eating and activity needs for herself and her family, she becomes more “able” to facilitate behavior change.

Participant population and recruitment

The target population consisted of postpartum women who were overweight or obese (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) [28] prior to pregnancy and their children aged 2–5, in 14 counties of the Triangle and Triad regions of North Carolina, USA. Postcards introducing the study were mailed to women identified from state birth certificate records who appeared eligible based on number of children and their ages. A purchased search for publicly available phone numbers based on the birth registry list yielded additional contact information for about half of this sample. Recruitment was augmented by posting flyers and brochures with a toll-free phone number in the larger obstetrics & gynecology and pediatric practices, in day care centers, and other community areas including libraries, local stores, and community bulletin boards.

Screening and eligibility

Women for whom phone numbers had been obtained from the birth registry sample and all who had called the toll-free number were screened for eligibility by telephone. Eligibility criteria included: delivery of a baby within the prior 1–6 months, a preschooler aged 2–5 years in the home, self-reported pre-pregnancy BMI ≥ 25, and no medical complications that would prevent daily physical activity in mother or preschooler. Additional criteria for the mother included knowledge of English, being at least 18 years of age, and having regular access to a telephone and mailing address.

Eligible and interested mother/child dyads attended an in-person individual baseline assessment at one of two study sites (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, or Duke University, Durham). At this visit, staff described the study in further detail and obtained written consent for enrollment. Mother and child’s height and weight were measured, and if the mother’s measured BMI was less than 25 kg/m2 she and her preschooler were not eligible for further participation.

Baseline assessments and randomization

Once enrolled and confirmed eligible, successful completion of the baseline questionnaire, activity monitoring, and dietary recall were required for randomization. The self-administered baseline questionnaire was mailed two weeks in advance of the in-person enrollment visit, but if not previously completed, was completed at the time of the visit. The questionnaire assessed diet and physical activity in the preschooler and mother, current parenting behaviors, components of the teachable moment, and the mother’s self-efficacy and motivation for behavior change. At the visit mother and child were provided with accelerometers which they both were instructed to wear for one week and mail back using a prepaid return envelope. During the 2 weeks following the visit the mother completed two interviewer-administered 24 hour dietary recalls by telephone using the Nutrition Data System for Research.

Once participants passed the run-period (completing all assessments, and as long as mothers were no more than 7 months postpartum) they were randomized to the study via permuted 8-block randomization, generated by SAS (Cary, NC).

All recruitment and enrollment procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Duke University Medical Center and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Intervention

Control arm

participants randomized to the control arm receive monthly newsletters emphasizing pre-reading skills in the preschooler, based on publicly-available pamphlets created through the Reading Is Fundamental (RIF) program (www.rif.org).

KAN-DO intervention

participants randomized to the intervention arm receive eight interactive family kits. Kits are mailed monthly and each is followed by a 20–30 minute supportive telephone counseling session based on motivational interviewing techniques. Mailed modules and telephone calls are supplemented with a group session where skills are reinforced by the counselor and study nutritionist.

The 8 month KAN-DO intervention focuses on the development of a healthy weight via instruction in parenting skills, techniques for stress management, and education about healthy behaviors. Parenting skill instruction emphasizes the establishment of routines and a supportive home environment, the improvement of the mother/child feeding relationship, the importance of stress management and self-care, and the mother as a positive role model for healthy eating and exercise behaviors. Education about healthy behavior changes for both the mother and preschooler target diet (decreased intake of sugary drinks and fast food, increase in fruit and vegetable consumption and meals prepared at home) and physical activity (increase in activity including time spent playing outdoors, and decrease in sedentary behavior including time spent watching TV).

Each kit is focused on a core topic and includes illustrated print materials for the mother, and a child activity that integrates the concepts from the mother’s print materials. The child activity is structured to encourage the dyad to work together towards the healthy behavior of the month. Incentives reinforcing the month’s topic, such as a rewards chart, yoga mat, pedometer, or portion plate, are included with each kit.

The skills taught via mailed intervention modules are reinforced by trained telephone counselors. Calls are made approximately one week after receipt of each module and used to review information in the module and address motivation, self-efficacy, and barriers to change. Consistent with the principles of motivational interviewing [26] the counselors use reflective listening techniques to elicit women’s personal and family goals for behavior changes and stress management.

In addition, women are asked to attend one group session anytime during the 8-month intervention period. At this semi-structured session, counselors and study nutritionists review general content from the family kits, but also set aside time for role play and group discussion. Sessions take place in the evenings and on Saturdays in the same building as the study visits, and a meal and free child care are provided.

Measures

Assessments are collected at entry to the study (2–6 months postpartum, baseline), end-of-intervention (10 months post-baseline, follow-up 1), and one year post-intervention (22 months post-baseline, follow-up 2). All participants receive monetary incentives (totaling $100) to complete assessments. Primary analyses relate to changes in the preschooler’s weight, diet and physical activity. Secondary analyses relate to the same outcomes in the mothers, changes in the mother’s parenting skills, and the possible impact of teachable moment factors on intervention effects.

Weight status

Standardized, measured weights and heights of the preschoolers are collected at all timepoints. Standardized, measured weight and waist circumference are collected from mothers at all timepoints, with height measured at baseline. Heights are measured using a SECA 214 portable stadiometer and weights using a Tanita BWB-800S digital scale, in street clothes with shoes removed. The main outcome of the study is change in child BMI z-score, an age- and gender- adjusted measure of child BMI. Change in mother’s BMI will be a secondary outcome. In secondary analysis, we will also assess change in the proportion of children at or above the 85th and 95th percentiles for weight.

Diet and activity

Mothers completed brief questionnaire items regarding daily intake of food items potentially related to obesity, reporting these separately for themselves and for their preschoolers. The items included intake of soda and other sweetened beverages [29–30], fast food [31–32], and fruits and vegetables [33–34] (reported at baseline and each follow-up), and have been used extensively in North Carolina public health programs [35]. At baseline and follow-up 1, dietary intake of the mother is measured on two randomly selected days over the two weeks following the study visit via a telephone-administered, multiple-pass, 24-hour dietary recall using the Nutrition Data System for Research [36–37]. Mean daily caloric intake and percent daily intake from fat will be derived from this data.

At baseline and follow-up 1, physical activity and sedentary behavior are measured in both the preschooler and mother using accelerometers [38–40]. The Actical accelerometer (model #198-0200, Mini-Mitter Co. Inc., Bend, Oregon), is a small, light-weight multi-axial accelerometer sensitive to movement in all directions. Mothers and preschoolers are asked to wear the belted monitors on the right hip continuously for 7 days, returning them in a self-addressed stamped envelope. Data are summarized as minutes of sedentary and of moderate/vigorous activity, using separate settings and cutpoints for mothers and children [41]. Questionnaire data including time spent watching TV and computer and video game time (both mother and preschooler), outdoor playtime (preschooler), and the Kaiser Permenente Activity Scale [42–43] (mother) are collected at baseline and both follow-ups.

Parenting skills

Parental feeding practices are measured by The Parental Feeding Style Questionnaire [44]. Family structure and routines around eating are measured by the Family Meal Questionnaire [45], and policies concerning the TV viewing environment were also measured [46]. Parenting self-efficacy is measured by the competency subscale of The Parenting Stress Index [47].

Teachable moment

Teachable moment factors are measured through a set of pre-existing and adapted measures, assessed at baseline. Weight-related affect questions are adapted from items on the Positive and Negative Affect Scale [48] to assess mother’s feelings about her own weight and that of her preschooler. The mother’s weight-related risk perceptions for her and for her preschooler are asked (e.g., “How likely is it that you will be overweight in two years if you continue to eat/be as physically active as you do/are now?” ). Self-image is assessed based on statements such as: “Since the birth of your baby, to what extent do you serve as a healthy role model for your children?” Also assessed at baseline and both follow-ups are motivation (e.g., How much do you want to make “healthy” changes in your preschooler’s eating habits?) and self-efficacy (e.g., How confident are you that you can make “healthy” changes in your preschooler’s eating habits?) to change weight, diet and physical activity.

Potential predisposing or mediating factors

Mother’s demographic measures include racial/ethnic group, education, insurance status, marital status, and ages of other children living at home. Child care arrangements and work outside the home are assessed at baseline and again at both follow-ups. Mother’s self-report of her preschooler’s birthweight, her own pre-pregnancy weight, and her gestational weight gain during the most recent pregnancy are collected at baseline. Additional measures in the mother include: duration and amount of breastfeeding (with both preschooler and current infant), contraception use, smoking status, overall self-reported health, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale [49], social support, and stress and coping measures [50]. The Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire [51] assesses parents’ perception of their child’s eating habits. We include the satiety responsiveness, slowness in eating, desire for drinks, and emotional overeating subscales. Child temperament is indicated by items from the demandingness subscale of the Parenting Stress Index and the bedtime resistance subscale of the Child Sleep Habits Questionnaire [52–53].

Intervention participation is indicated by records of attendance at the group session and participation in the telephone counseling sessions. At each call counselors subjectively rate the woman’s engagement in the behavior change process, and ask about use of child activities and whether the mother read the materials. Extent and quality of involvement with the family kit activities is assessed through returned “homework assignment” postcards (5 questions regarding content of kit or outcomes of activity). Women receive $5 for each returned homework assignment.

Statistical considerations

Within sixteen strata defined by study site (Durham vs. Greensboro), child’s age (2–3 vs. 4–5), mother’s days postpartum (<122 days vs. ≥ 122 days) and mother’s race (black vs. non-black), a total of 400 preschooler/mother dyads were randomized with equal allocation to the KAN-DO intervention and control arms. We expect about 60 dyads will drop out before follow-up 2; these dropouts will be included in analyses by assuming no change in behavior across time. The study has seven primary endpoints, all of which involve changes in the preschooler. The first and most important endpoint is change from baseline to follow-up 2 in BMI z-score. The remaining six endpoints are change from baseline to follow-up 1 in number of servings of sugary drinks, number of fast food meals, number of servings of fruits and vegetables, physical activity and inactivity as measured by the activity monitors, and time spent watching television. General linear models will be used to test whether the arms differ on each of these endpoints, controlling for the baseline value of the endpoint. The overall experiment-wise alpha level will be controlled at 0.05 by using a 1-sided alpha of 0.05/7 for each of the seven tests. With 200 participants per arm, the t-test has 90% power when the true standardized mean arm difference is 0.374. According to Cohen [54], this effect size is between “small” and “medium” in size.

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

Four hundred dyads were randomized to the trial between September 2007 and November 2009. Of these, 67% are attending at the Durham site and 33% at the Greensboro site. With regard to other stratification factors, 31% of preschoolers were aged 4 or 5 years and 90% of mothers were less than 122 days postpartum at baseline, and 22% of mothers are black. Participating mothers have a mean age of 32.5 (SD 4.9) years and a mean baseline measured BMI of 32.8 (SD 5.6) kg/m2.

Baseline sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. About 40% of mothers were overweight at baseline and the remaining were obese (BMI ≥ 30). Mothers are 75% white and most are married (86%). More than half have a college or postgraduate education and household incomes of $60,000 or more. Though this demonstrates high representation of affluent households, 19% of our sample reports an income of $30,000 or below, and 25% are uninsured or insured through Medicaid. About a third of mothers have three or more children, and about half are working outside the home.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of mother-child dyads in the study sample

| Variable | n=400 % (n) |

|---|---|

| Child | |

| Age | |

| 2 years | 35.8 (143) |

| 3 years | 33.0 (132) |

| 4 years | 20.5 (82) |

| 5 years | 10.8 (43) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 55.8 (223) |

| Female | 44.3 (177) |

| Mother | |

| Age | |

| <30 | 26.3 (105) |

| 30–35 | 35.8 (143) |

| >35 | 38.0 (152) |

| Race | |

| White | 75.3 (301) |

| Black | 21.8 (87) |

| Other races | 3.0 (12) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 4.8 (19) |

| Education | |

| High school graduate or less | 11.5 (46) |

| Some college | 20.3 (81) |

| College degree | 42.0 (168) |

| Graduate school | 26.3 (105) |

| Marital status | |

| Single/never married | 8.3 (33) |

| Living with a partner | 3.8 (15) |

| Married | 86.5 (346) |

| Separated/divorced | 1.5 (6) |

| Household income | |

| Up to $15,000 | 10.2 (40) |

| $15,001 – $30,000 | 8.9 (35) |

| $30,001 – $45,000 | 9.1 (36) |

| $45,001 – $60,000 | 15.2 (60) |

| $60,001 or more | 56.6 (223) |

| Insurance status* | |

| Private/through employer | 79.5 (318) |

| Medicaid | 18.8 (75) |

| None | 6.0 (24) |

| Parity | |

| Two children | 68.0 (272) |

| Three or more | 32.0 (128) |

| Work outside the home | |

| Full-time | 29.8 (119) |

| Part-time | 19.0 (76) |

| Not work for pay | 51.3 (205) |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 39.0 (156) |

| Obese class I (30–34.9) | 32.0 (128) |

| Obese class II (35–39.9) | 17.0 (68) |

| Obese class III (40+) | 12.0 (48) |

Respondents were allowed to report any/multiple insurance sources; may not add to 100%

At baseline 24% of enrolled preschoolers are already classified as overweight or obese (Table 2). 30% of preschoolers have at least one serving of sugary drinks (soda or other sweetened beverages) per day, 60% have at least one fast food meal per week, and 17% have the recommended 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day. Valid accelerometry data (at least 6 hours of continuous wear on at least 2 weekdays and 1 weekend day) was collected on 84% of the sample. Of these, no children in the study have at least one hour of moderate/vigorous activity per day. 44% of the preschoolers watch more than 2 hours of television daily.

Table 2.

Baseline weight and behavioral characteristics of target children

| Variable | n=400 %(n)* |

|---|---|

| Weight | |

| Mean (SD) BMI z-score | 0.44 (0.97) |

| BMI category | |

| Underweight (< 5th percentile) | 2.5 (10) |

| Normal weight (5th–85th percentile) | 73.5 (294) |

| Overweight (>85th–95th percentile) | 15.3 (61) |

| Obese (>95th percentile) | 8.8 (35) |

| Dietary intake | |

| At least one serving of sugary drinks/day | 30.1 (120) |

| At least one fast food meal/week | 59.5 (238) |

| At least 5 servings fruits and vegetables/day | 17.3 (69) |

| Physical activity and inactivity | |

| Mean (SD) minutes moderate/vigorous activity/day (n=337) | 14.9 (9.6) |

| Mean (SD) minutes sedentary time/day (n=337) | 367.0 (82.1) |

| Watch > 2 hours of TV/day | 44.0 (176) |

except where noted

DISCUSSION

The KAN-DO trial adds to the growing body of research aimed at the prevention of childhood obesity. Family-based intervention continues to be an important area of research, and there is recognition of the value of targeting parents as agents of change [55–56]. However, few previous trials have focused specifically on parenting skills or practices as intervention targets. The Families for Health trial in the UK incorporated elements of the UK-based Family Links Nurturing Programme, which emphasizes parenting and family lifestyle [57], and Golley et al. tested an intervention designed to “promote parental competence to manage their child’s behavior” [58]. Both these trials were conducted in older children than those in KAN-DO (7–13 in the former, 6–9 years in the latter).

The age of the target children is also a novel element of the KAN-DO study. As overweight has become more widespread in ever younger children [59], the importance of early intervention has become more evident. A recent review of obesity prevention studies in children 0 to 5 years found a total of 23 such interventions [60]. Of these, only five targeted weight as the primary outcome (as opposed to dietary intake or activity behaviors) and all five were conducted in preschool/child care settings. Eight family-based interventions were found, only one of which involved parenting practices as an intervention target. The Community Mothers Programme was a randomized controlled trial of a peer-delivered parenting intervention for disadvantaged first-time mothers. Conducted in Ireland in 1989, the program showed promising results in areas of parenting practices and child dietary intake, but has not been replicated [61–62].

Design considerations

Women who were overweight or obese prior to pregnancy were selected based on published studies indicating their children are at increased risk of overweight and obesity. The mother is the target of intervention since she is more commonly the main “gatekeeper” for the preschooler and the family; moreover, this design allows single mother households to take part.

The two-arm design enables us to assess differences between the intervention and control groups with adequate statistical power and sample size that can be accrued feasibly within the 20 month recruitment window. A more complex four-arm design including families without a newborn would have been optimal to evaluate our teachable moment hypothesis; aside from the increase in sample size this would have required, an intervention for non-postpartum women would by design have been different than KAN-DO, making comparisons complicated.

Short-term weight loss or weight control is much easier to achieve than longer term weight loss. Our primary endpoint (BMI z-score change at approximately 2 years post-baseline) strikes the balance between following the preschoolers and their mothers long enough to assess long-term outcomes with what is feasible within a 5 year study period.

Limitations

Our sample has an adequate representation of both white and black children and their mothers, from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds. However, the women who enrolled tend to be better educated and more likely to be married than postpartum women in the recruitment area.

We originally proposed to collect 24-hour dietary recalls only on the mothers, because at the time this method (child intake via mother-report) had not been validated in children ages 2–5. We have, however, collected dietary recalls on a subsample of the participating children in the study at baseline, and will attempt to collect recalls from these same participants at follow-up 1, using the same methods outlined for the mothers in the study.

We aimed to intervene with the preschoolers just after a subsequent sibling had been born. This may be a teachable moment for reinforcing healthy behaviors and changing unhealthy behaviors, however, it limits the target population. For our study, this requirement has meant that recruitment has taken longer and has had to span a larger geographical area to reach the target sample size. Also, this may also have precluded mothers with fewer resources from taking part; caring for a newborn in addition to a preschooler requires more time and effort, and may make participation in research less likely for mothers without a strong support system [63–64]. This creates a dilemma, since such mothers and their preschoolers may at the same time be those at highest risk and therefore most in need of an intervention.

Conclusion

In order for a mother to become an agent for change via a family-based intervention, she must be willing and able to consider changes for herself. The postpartum period is a time when women are at risk for weight retention and might be particularly open to considering weight-related changes. By equipping postpartum mothers with sound parenting practices, stress management techniques, and skills for creating behavior change in herself and her child, a family-based obesity prevention program such as KAN-DO may prove to be an effective mechanism for reducing the incidence of childhood obesity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the following faculty and staff who contributed to the development and execution of this project:

Terrill Bravender

Elizabeth Tilson

Jessica Revels

Andrew DeGraff

Nedenia Parker

Sarah Rohan

Nathena McDaniel

Christy Boling-Turer

Diane Gifford

Anne Bowman

LaCrystal Strong

Lauren Coon

Gina Moening

Erin Street

Karyn Sailstad

Hannah Harvey

FUNDING

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01-DK-75439).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):242–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington D.C: National Academies Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlow SE, Dietz WH. Obesity evaluation and treatment: Expert Committee recommendations. The Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration and the Department of Health and Human Services. Pediatrics. 1998;102(3):E29. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.3.e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(13):869–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golan M, Crow S. Parents are key players in the prevention and treatment of weight-related problems. Nutrition Reviews. 2004;62(1):39–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golan M, Weizman A, Fainaru M. Impact of treatment for childhood obesity on parental risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Prev Med. 1999;29(6 Pt 1):519–26. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wrotniak BH, Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Roemmich JN. Parent weight change as a predictor of child weight change in family-based behavioral obesity treatment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(4):342–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birch LL, Fisher JO. Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3 Pt 2):539–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birch LL. Development of food preferences. Ann Rev Nutr. 1999;19:41–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Perry C, Story M. Correlates of fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents. Findings from Project EAT. Prev Med. 2003;37(3):198–208. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birch LL, Davison KK. Family environmental factors influencing the developing behavioral controls of food intake and childhood overweight. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48(4):893–907. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70347-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birch LL, Fisher JO. Mothers’ child-feeding practices influence daughters’ eating and weight. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000:1054–61. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birch LL, Fisher JO, Davison KK. Learning to overeat: maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes girls’ eating in the absence of hunger. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(2):215–20. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brody GH, et al. The Strong African American Families Program: translating research into prevention programming. Child Development. 2004;75(3):900–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wills TA, et al. Family communication and religiosity related to substance use and sexual behavior in early adolescence: a test for pathways through self-control and prototype perceptions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17(4):312–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zucker NL, Ferriter C, Best S, Brantley A. Group parent training: a novel approach for the treatment of eating disorders. Eating Disorders. 2005;13(4):391–405. doi: 10.1080/10640260591005272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(3):390–5. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krummel DA, Semmens E, Boury J, Gordon PM, Larkin KT. Stages of change for weight management in postpartum women. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004 Jul;104(7):1102–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: the case of smoking cessation. Health Educ Res. 2003 Apr;18(2):156–70. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Østbye T, Krause KM, Brouwer RJN, Lovelady CA, Morey MC, Bastian LA, Swamy GK, Chowdhary J, McBride CM. Active Mothers Postpartum (AMP): rationale, design and baseline characteristics. J Womens Health. 2008;17(10):1567–75. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brody GH, et al. Unique and protective contributions of parenting and classroom processes to the adjustment of African American children living in single-parent families. Child Development. 2002;73(1):274–86. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim IJ, et al. Parenting behaviors and the occurrence and co-occurrence of depressive symptoms and conduct problems among african american children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17(4):571–83. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bandura A. Social learning through imitation. In: Jones Marshall R., editor. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. 1962. pp. 211–274.pp. xiiipp. 330 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandura A, Ross D, Ross SA. Vicarious reinforcement and imitative learning. Journal of Abnormal & Social Psychology. 1963;67(6):601–607. doi: 10.1037/h0045550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hochbaum GM. Public participation in medical screening programs: a sociopsychological study. Washington, DC: U.S. Public Health Service; 1958. Publication No. (PHS)572. [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. NIH publication no.98-4083. National Institutes of Health; Sep, 1998. [Accessibility verified September 28, 2010]. Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel. Also available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/ob_gdlns.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 Aug;84(2):274–88. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubois L, Farmer A, Girard M, Peterson K. Regular sugar-sweetened beverage consumption between meals increases risk of overweight among preschool-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007 Jun;107(6):924–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowman SA, Gortmaker SL, Ebbeling CB, Pereira MA, Ludwig DS. Effects of fast-food consumption on energy intake and diet quality among children in a national household survey. Pediatrics. 2004 Jan;113(1 Pt 1):112–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowman SA, Vinyard BT. Fast food consumption of U.S. adults: impact on energy and nutrient intakes and overweight status. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004 Apr;23(2):163–8. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ledoux TA, Hingle MD, Baranowski T. Relationship of fruit and vegetable intake with adiposity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2010 Jul 14; doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00786.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alinia S, Hels O, Tetens I. The potential association between fruit intake and body weight--a review. Obes Rev. 2009 Nov;10(6):639–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/

- 36.Jonnalagadda SS, Mitchell DC, Smiciklas-Wright H, Meaker KB, Van Heel N, Karmally W, Ershow AG, Kris-Etherton PM. Accuracy of energy intake data estimated by a multiple-pass, 24-hour dietary recall technique. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100(3):303–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(00)00095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tran KM, Johnson RK, Soultanakis RP, Matthews DE. In-person vs telephone-administered multiple-pass 24-hour recalls in women: validation with doubly labeled water. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100(7):777–83. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Puyau M, Adolph A, Vohra F, Butts N. Validation and calibration of physical activity monitors in children. Obes Res. 2002;10(3):150–7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puyau MR, Adolph AL, Vohra FA, Zakeri I, Butte NF. Prediction of activity energy expenditure using accelerometers in children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004 Sep;36(9):1625–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klippel N, Heil D. Validation of energy expenditure prediction algorithms in adults using the Actical electronic activity monitor. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(5 supplement) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfeiffer KA, McIver KL, Dowda M, Almeida MJ, Pate RR. Validation and calibration of the Actical accelerometer in preschool children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006 Jan;38(1):152–7. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000183219.44127.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ainsworth BE, Sternfeld B, Richardson MT, Jackson K. Evaluation of the kaiser physical activity survey in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(7):1327–38. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200007000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blum JW, Beaudoin CM, Caton-Lemos L. Physical activity patterns and maternal well-being in postpartum women. Matern Child Health J. 2004;8(3):163–9. doi: 10.1023/b:maci.0000037649.24025.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wardle J, Sanderson S, Guthrie CA, Rapoport L, Plomin R. Parental feeding style and the inter-generational transmission of obesity risk. Obes Res. 2002;10(6):453–62. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neumark-Sztainer D, et al. Are family meal patterns associated with disordered eating behaviors among adolescents? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:350–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hesketh K, Ball K, Crawford D, Campbell K, Salmon J. Mediators of the relationship between maternal education and children’s TV viewing. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(1):41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index. 3. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crawford JR, Henry JD. The positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2004 Sep;43(Pt 3):245–65. doi: 10.1348/0144665031752934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987 Jun;150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Birch LL, et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: a measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite. 2001;36(3):201–10. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M. The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): Psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep. 2000;23(8):1043–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarason IG, Sarason BR. Social Support: Theory, Research and Applications. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; Seattle, Washington, USA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goodlin-Jones BL, Sitnick SL, Tang K, Liu J, Anders TF. The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire in toddlers and preschool children. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29(2):82–88. doi: 10.1097/dbp.0b013e318163c39a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Okely AD, Collins CE, Morgan PJ, Jones RA, Warren JM, Cliff DP, Burrows TL, Colyvas K, Steele JR, Baur LA. Multi-site randomized controlled trial of a child-centered physical activity program, a parent-centered dietary-modification program, or both in overweight children: the HIKCUPS study. J Pediatr. 2010 Sep;157(3):388–94. 394.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Janicke DM, Sallinen BJ, Perri MG, Lutes LD, Huerta M, Silverstein JH, Brumback B. Comparison of parent-only vs family-based interventions for overweight children in underserved rural settings: outcomes from project STORY. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008 Dec;162(12):1119–25. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.12.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robertson W, Friede T, Blissett J, Rudolf MC, Wallis M, Stewart-Brown S. Pilot of “Families for Health”: community-based family intervention for obesity. Arch Dis Child. 2008 Nov;93(11):921–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.139162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Golley RK, Magarey AM, Baur LA, Steinbeck KS, Daniels LA. Twelve-month effectiveness of a parent-led, family-focused weight-management program for prepubertal children: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2007 Mar;119(3):517–25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010 Jan 20;303(3):242–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hesketh KD, Campbell KJ. Interventions to prevent obesity in 0–5 year olds: an updated systematic review of the literature. Obesity Feb. 2010;18 (Suppl 1):S27–35. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnson Z, Howell F, Molloy B. Community mothers’ programme: randomised controlled trial of non-professional intervention in parenting. BMJ. 1993 May 29;306(6890):1449–52. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6890.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johnson Z, Molloy B, Scallan E, Fitzpatrick P, Rooney B, Keegan T, Byrne P. Community Mothers Programme--seven year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of non-professional intervention in parenting. J Public Health Med. 2000 Sep;22(3):337–42. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/22.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Østbye T, Krause KM, Lovelady CA, Morey MC, Bastian LA, Peterson BL, Swamy GK, Brouwer RJ, McBride CM. Active Mothers Postpartum: a randomized controlled weight-loss intervention trial. Am J Prev Med. 2009 Sep;37(3):173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carter-Edwards L, Østbye T, Bastian LA, Yarnall KSH, Krause KM, Simmons TJ. Barriers to adopting a healthy lifestyle: insight from postpartum women. BMC Research Notes. 2009;2:16. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.