Abstract

Experiment 1 examined comodulation masking release (CMR) for a 700-Hz tonal signal under conditions of NoSo (noise and signal interaurally in phase) and NoSπ (noise in phase, signal out of phase) stimulation. The baseline stimulus for CMR was either a single 24-Hz wide narrowband noise centered on the signal frequency [on-signal band (OSB)] or the OSB plus, a set of flanking noise bands having random envelopes. Masking noise was either gated or continuous. The CMR, defined with respect to either the OSB or the random noise baseline, was smaller for NoSπ than NoSo stimulation, particularly when the masker was continuous. Experiment 2 examined whether the same pattern of results would be obtained for a 2000-Hz signal frequency; the number of flanking bands was also manipulated (two versus eight). Results again showed smaller CMR for NoSπ than NoSo stimulation for both continuous and gated masking noise. The CMR was larger with eight than with two flanking bands, and this difference was greater for NoSo than NoSπ. The results of this study are compatible with serial mechanisms of binaural and monaural masking release, but they indicate that the combined masking release (binaural masking-level difference and CMR) falls short of being additive.

INTRODUCTION

This study investigated signal detection in conditions where both masking-level difference (MLD) cues (Hirsh, 1948; Licklider, 1948) and comodulation masking release (CMR) cues (Hall et al., 1984) were present simultaneously. The results of several studies have shown that such conditions often result in masking release that is greater than for either type of cue (MLD or CMR) alone (Hall et al., 1988; Schooneveldt and Moore, 1989; Cohen and Schubert, 1991; Hall et al., 2006; Epp and Verhey, 2009a). In the tasks investigated here, the MLD is defined as the difference in threshold between a condition where both the masking noise and signal are interaurally in phase (NoSo) and a condition where the masker is interaurally in phase and the signal is interaurally out of phase (NoSπ). For relatively low-frequency signals, the MLD for a tone masked by a single narrow band of noise centered on the signal frequency is quite large for many listeners, with the NoSπ threshold often being more than 15 dB lower than the NoSo threshold (e.g., Bernstein et al., 1998; van de Par and Kohlrausch, 1999; Buss et al., 2007). One question addressed in some previous investigations is how much improvement in the NoSπ threshold is obtained when comodulated No flanking bands are added to the on-signal band (OSB). Results have indicated that there are individual differences in the magnitude of the improvement resulting from the addition of comodulated flanking bands, with values ranging from approximately −1 to + 6 dB (Hall et al., 1988; Hall et al., 2006). This improvement in the NoSπ threshold has sometimes been referred to as the “binaural CMR,” reflecting the fact that the detection is based, at least in part, upon the binaural difference cues. Note that the added, comodulated No flanking bands provide cues related to the masker envelope but do not provide any additional binaural difference cues. This binaural CMR, referenced against the OSB baseline, has been found to be 6–11 dB smaller than the CMR obtained in the associated NoSo conditions (e.g., Hall et al., 2006; Epp and Verhey, 2009a). However, Epp and Verhey (2009a) have recently pointed out that a baseline for binaural CMR, where random flanking bands are present, may be more appropriate than the OSB baseline. This is because the binaural difference cues available in NoSπ stimulation may differ between the OSB condition and the conditions where flanking bands are added. This point will be considered further in Sec. II B. In the study of Epp and Verhey (2009a), calculating CMR using the random flanking-band baseline resulted in equivalent CMRs for NoSo and NoSπ stimulation, with a magnitude of approximately 10 dB in both cases. Epp and Verhey (2009a) suggested that the equivalence of the NoSo and NoSπ CMRs supported an interpretation in terms of serial CMR and MLD processes, wherein “the first stage does not alter the information needed in the second stage” (Epp and Verhey, 2009b).

Epp and Verhey (2009a) pointed out an inconsistency between their results and the results of Hall et al. (2006). Using a random-masker baseline for computing CMR, Epp and Verhey found similar CMRs for NoSo and NoSπ conditions, whereas Hall et al. found a smaller CMR for NoSπ than NoSo. Epp and Verhey noted that the noise bands were spaced more widely in their study than in the study of Hall et al., and they speculated that the CMR results with the closer spacing were influenced by a within-channel effect. Such an effect may be associated with the beating pattern arising from comodulated bands and the change in the regularity of that pattern when a signal is added to one of the bands (Schooneveldt and Moore, 1987). Epp and Verhey further speculated that additive MLD∕CMR effects may occur only when the CMR arises from across-channel processes.

EXPERIMENT 1: EFFECTS OF MASKER GATING AT 700 Hz

The purpose of the present study was to test further the idea that MLD and CMR effects are additive for relatively widely spaced flanking bands. A variable of interest in this study was whether the noise stimuli were presented continuously or only during the observation intervals (gated). Previous studies have indicated that the monaural CMR is sometimes larger for continuous than gated noise (McFadden and Wright, 1992; Fantini et al., 1993; Hatch et al., 1995), but there are no previous data on the effect of noise gating for binaural CMR. This could be an important point in accounting for the different outcomes for binaural CMR in the study of Hall et al. (2006), where continuous masking noise was used, and the study of Epp and Verhey (2009a), where gated masking noise was used.

Methods

Procedures and conditions

Most of the conditions were patterned after the Gaussian noise conditions in experiment 1 of Epp and Verhey (2009a) to allow comparison between studies. Signal thresholds for a 700-Hz pure-tone signal (250-ms duration, including 50-ms onset and offset ramps) were measured in NoSo and NoSπ conditions. The masker was either a single narrow band of noise centered on the 700-Hz signal frequency (OSB) or a multi-band stimulus, composed of the OSB plus flanking bands centered on 300, 400, 1000, and 1100 Hz. Although the flanking bands were spectrally near to each other on both the low- and high-frequency sides, the spectral spacing between the flanking bands and the OSB was relatively wide in order to reduce the availability of within-channel cues. Each masker was 24 Hz wide and had a level of 60 dB sound pressure level (SPL). Maskers were generated at the beginning of each threshold estimation track from new independent draws from a Gaussian distribution. Each masker was composed of 216 points. When played at 6103 Hz, this resulted in a 10.7-s sample that repeated seamlessly. Noise bands were generated in the frequency domain by assigning random draws from a normal distribution for the associated real and imaginary components. For the comodulated noise, a single set of random draws was used for all five noise bands. For the random noise, different sets of random draws were used for each of the five bands. The masker arrays were transformed to the time domain using an inverse fast Fourier transform (FFT). Masking noise was played either continuously or gated on during listening intervals for 500 ms, including 50-ms raised cosine onset and offset ramps. Stimuli were played through two channels of a real-time processor (RP2, Tucker-Davis Technologies), routed through a headphone buffer (HB7, TDT), and presented to the listener using a pair of insert earphones (ER2, Etymotic).

A three-alternative forced-choice procedure was used, with listening intervals and inter-stimulus intervals of 500 ms. The signal was presented in the temporal center of one of the 500-ms listening intervals, at random. Lights on a handheld response box indicated listening intervals and provided correct answer feedback after each response.

Thresholds were estimated using a two-down, one-up stepping rule converging on 71% correct (Levitt, 1971). Each track began with a signal level above the anticipated threshold. Prior to the first two track reversals, the signal level was adjusted in steps of 4 dB, with steps of 2 dB thereafter.1 Eight reversals were obtained, and the mean signal level at the last six reversals was taken as the threshold estimate. Three threshold estimates were obtained in each condition, and a fourth was collected in cases where the first three spanned a range of 3 dB or more. All thresholds were collected and blocked by condition, with the order of conditions randomized across listeners.

Listeners

There were nine listeners, six females and three males. Listeners had audiometric thresholds that were better than 20 dB hearing level (HL) at octave frequencies from 250 to 8000 Hz (ANSI, 2004). Listener age ranged between 24 and 51 yr. All listeners had previous listening experience in MLD experiments and seven had experience in CMR experiments. Listeners L8 and L9 had no previous experience in CMR listening. No additional practice was provided.

Results and discussion

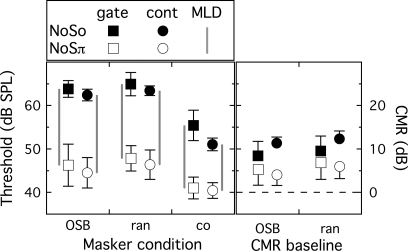

Individual masked threshold data are shown in Table TABLE I.. Mean masked threshold data are shown in the left panel of Fig. 1. The length of the gray lines in this panel provides an indication of the size of the MLD in the various conditions. Because the primary focus of this study is on CMR, the mean CMR values are plotted separately in the right panel of Fig. 1. For ease of inspection, CMRs for the gating variable are differentiated both in terms of symbol (circle for continuous noise and square for gated noise) and in terms of axis offset (continuous noise CMRs are offset to the right of gated noise CMRs). The CMR data were analyzed by performing a three-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with factors phase (So or Sπ), gating (continuous or gated), and baseline (OSB or random noise). This analysis showed a significant effect of phase (F1,8 = 41.0; p < 0.001), due to the fact that CMRs were larger for NoSo than NoSπ. The main effects of gating (F1,8 = 1.6; p = 0.24) and baseline (F1,8 = 3.6; p = 0.09) were not statistically significant. However, the interaction between phase and gating was significant (F1,8 = 7.9; p = 0.02). Simple effects testing (Kirk, 1968) was conducted using the EMMEANS subcommand of the SPSS statistics package. This analysis indicated that the phase X gating interaction arose due to the fact that CMR was greater for continuous than gated noise for NoSo, but the effect of gating was not significant for NoSπ (p > 0.05). Also, CMR was 6–7 dB smaller for NoSπ than NoSo in continuous noise, but only about 3 dB smaller for gated noise. A possible reason for the interaction between phase and gating will be introduced below following the discussion of a related MLD effect. Neither of the remaining two-way interactions (phase X baseline and gating X baseline) nor the three-way interactions were statistically significant (p > 0.05).2

Table 1.

Individual data, along with means and standard deviations (SD), for experiment 1.

| Gated | Continuous | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NoSo | NoSπ | NoSo | NoSπ | |||||||||

| OSB | comod | ran | OSB | comod | ran | OSB | comod | ran | OSB | comod | ran | |

| L1 | 61.9 | 51.7 | 61.3 | 37.0 | 38.2 | 43.1 | 60.8 | 50.8 | 61.7 | 40.0 | 37.4 | 39.8 |

| L2 | 61.7 | 54.3 | 63.3 | 41.9 | 41.2 | 47.2 | 61.2 | 52.1 | 62.5 | 41.2 | 38.8 | 43.4 |

| L3 | 63.7 | 51.1 | 65.3 | 45.8 | 37.1 | 48.8 | 62.3 | 49.7 | 63.8 | 44.8 | 40.2 | 46.0 |

| L4 | 64.2 | 53.4 | 61.8 | 45.6 | 39.7 | 50.2 | 62.0 | 52.0 | 62.1 | 45.4 | 39.4 | 47.4 |

| L5 | 62.8 | 54.3 | 64.2 | 47.4 | 39.6 | 49.2 | 61.9 | 51.1 | 63.8 | 44.2 | 39.8 | 50.8 |

| L6 | 62.3 | 59.8 | 66.1 | 47.0 | 42.7 | 46.1 | 63.5 | 51.0 | 63.8 | 45.4 | 41.0 | 46.2 |

| L7 | 66.2 | 54.2 | 69.9 | 46.4 | 42.2 | 48.9 | 63.0 | 49.9 | 63.5 | 42.8 | 42.0 | 50.7 |

| L8 | 64.2 | 59.3 | 67.1 | 52.5 | 43.4 | 52.5 | 61.7 | 49.1 | 64.4 | 44.2 | 42.0 | 46.7 |

| L9 | 67.2 | 60.3 | 65.2 | 52.8 | 44.8 | 44.6 | 65.2 | 53.8 | 65.0 | 52.3 | 43.2 | 46.6 |

| Mean | 63.8 | 55.4 | 64.9 | 46.3 | 41.0 | 47.8 | 62.4 | 51.1 | 63.4 | 44.5 | 40.4 | 46.4 |

| SD | 1.9 | 3.5 | 2.7 | 4.9 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 3.5 | 1.8 | 3.4 |

Figure 1.

Mean results for experiment 1 (700-Hz signal). In the left panel, mean thresholds are plotted as a function of masker condition, either OSB, random flanking bands (ran), or comodulated bands (co). Gray bars in the left panel indicate the magnitude of the MLD. In the right panel, the mean CMR is plotted as a function of baseline, either OSB or ran. Symbol shape indicates the gating condition, and symbol fill represents the signal phase condition, as defined in the legend. Error bars indicate one standard deviation across all listeners.

As evident in the left panel of Fig. 1, the MLD tended to be smaller for the conditions with the comodulated flanking bands than the conditions with the random flanking bands, particularly for the continuous noise case. A repeated measure ANOVA was performed on the MLD values, with factors of comodulation (comodulated or random flanking bands) and gating (continuous or gated). The analysis showed a significant effect of comodulation (F1,8 = 30.6; p = 0.001), a non-significant effect of gating (F1,8 = 4.0; p = 0.08), and a significant interaction between comodulation and gating (F1,8 = 7.0; p = 0.03). Simple effects testing indicated that the interaction was due to the MLD being particularly small in the comodulated, continuous condition. Inspection of the left panel of Fig. 1 indicates that this was due to the NoSo threshold being lower in the continuous than the gated conditions (the NoSπ thresholds were similar between continuous and gated noise). This agrees with the CMR analysis, above, showing relatively large CMR for the continuous NoSo condition.

The significant interaction found between phase and gating in the ANOVA examining the CMR data and the significant interaction between comodulation and gating just considered in the ANOVA examining the MLD are driven by the same factor; in the comodulated case, masker continuity resulted in an improvement in the NoSo threshold but not the NoSπ threshold. Previous studies have interpreted the larger monaural CMR in continuous noise than gated noise in terms of auditory grouping and the cues that help segregate a signal from a masker background (e.g., Fantini et al., 1993; Hall et al., 1996). By this account, the comodulated OSB and flanking bands form an auditory steam that is perceptually segregated from the signal. The short-duration masker segments available to the listener in gated conditions may prevent the full formation of an auditory stream associated with the masker, consistent with the finding of McFadden and Wright (1992) that CMR continued to increase with duration of a forward fringe on the masker out to the longest fringe tested (445 ms). An effect compatible with previous results on masker gating was observed here for NoSo but not for NoSπ. A possible reason why masker continuity did not have a beneficial effect for NoSπ could again be related to cues for signal∕masker segregation. The very low NoSπ thresholds for low-frequency tones, even in baseline conditions, suggest that the binaural difference cues are effective in segregating the signal from the masker. Buss and Hall (2011) have shown that the binaural difference cues are also very effective in segregating signal from masker in a forward masking paradigm. It is possible that a perceptual segregation benefit related to continuous presentation of the comodulated bands was not seen in the NoSπ conditions of the present experiment because binaural difference cues provided this kind of benefit in both the continuous and gated conditions.

The present findings may be useful in interpreting the discrepancy between the binaural CMR results of Hall et al. (2006) for a 500-Hz signal and those of Epp and Verhey (2009a) for a 700-Hz signal. Recall that the noise was continuous in the study of Hall et al. and gated in the study of Epp and Verhey. Whereas Epp and Verhey found that the NoSπ CMR was approximately the same as the NoSo CMR using the random noise baseline, Hall et al. found that the NoSπ CMR was only about half the value of the NoSo CMR for that baseline. Epp and Verhey suggested that this difference could be related to the use of within-channel cues in the Hall et al. study. The present results suggest an alternative interpretation: that the difference in results between studies might arise from the fact that gated noise was used by Epp and Verhey (2009a), whereas continuous noise was used by Hall et al. (2006). Using the same frequency spacing as in Epp and Verhey (2009a), the present study replicated the Hall et al. (2006) finding. That is, using the random noise baseline, the NoSπ CMR was approximately half the value of the NoSo CMR for a continuous noise masker. The present results also indicated that the difference between the NoSo and NoSπ CMR diminished for gated noise, a finding that is broadly consistent with the finding of Epp and Verhey that the NoSπ CMR was relatively large in their gated noise paradigm.

A finding of interest in the present study was that, with respect to the OSB baseline, most listeners showed a Sπ threshold improvement of at least 2 dB when comodulated flanking bands were added (see Table TABLE I.). This was true for eight of nine listeners for continuous noise and seven of nine listeners for gated noise. Previous studies using a signal frequency of 500 Hz and a band separation of 100 Hz generally showed that only about half of listeners tested showed an improvement in Sπ threshold (e.g., Hall et al., 2006). Hall et al. (2006) noted that one effect of the flanking bands might be to mask off-frequency NoSπ cues that could aid the binaural detection (van de Par and Kohlrausch, 1999; Breebaart et al., 2001), a point that was also made by Epp and Verhey (2009a). Breebaart et al. (2001) assumed that the Sπ detection in No noise is limited by internal noise associated with the binaural detection process. They further assumed that, for a narrowband masker, the binaural cues associated with the masker + signal are highly correlated across the different frequency channels to which excitation spreads and that internal noise is uncorrelated across the frequency channels. With these assumptions, they argued that the detection of the Sπ signal in a narrowband masker benefits from an integration of binaural cues across the excitation pattern. Although the addition of comodulated flanking bands could have a beneficial effect related to CMR, the bands might also have a negative effect related to the masking of the spread of excitation cues (van de Par and Kohlrausch, 1999; Breebaart et al., 2001). It is possible that the relatively wide frequency separation between the OSB and the flanking bands used in the present study was responsible for the finding that comodulated flanking bands were more likely to result in a binaural CMR with respect to the OSB baseline than found in previous studies using a 500-Hz signal frequency and a band frequency separation of 100 Hz. With a frequency separation of 100 Hz, the added comodulated bands may have caused a negative effect whereby spread of excitation cues was masked. The wider band separation used here could have reduced this type of masking effect, making it more likely for a positive effect related to comodulation to emerge.

Inspection of the NoSπ noise results in Table TABLE I. indicates that the listeners with the best OSB thresholds (e.g., L1 and L2 in the gated condition) had relatively small or absent binaural CMRs (referenced to the OSB threshold). Conversely, listeners with the poorest NoSπ thresholds in the OSB masker (e.g., L8 and L9 in the gated condition) tended to have larger binaural CMRs. There was a significant correlation between the OSB threshold and the improvement gained by adding comodulated bands both for the gated (r = 0.86; p = 0.003) and the continuous (r = 0.87; p = 0.002) noise conditions. One way of thinking about this is that listeners who made very effective use of binaural cues in the NoSπ OSB condition may have had little room for improvement when adding comodulated noise bands.

EXPERIMENT 2: EFFECTS OF MASKER GATING AND NUMBER OF FLANKING BANDS AT 2000 Hz

Experiment 2 was performed at a higher signal frequency of 2000 Hz. One motivation for this was to determine whether the pattern of results observed in experiment 1 also occurs at a higher frequency. An additional motivation was related to the fact that a higher signal frequency makes it easier to use a larger number of relatively widely spaced flanking bands placed symmetrically above and below the signal in frequency. Previous results indicate that CMR for monaural or diotic stimuli often increases with increasing number of flanking bands (Schooneveldt and Moore, 1989; Hall et al., 1990). It was of interest to determine whether the same effect of flanking-band number occurs under conditions of NoSπ stimulation, as would be expected for an additive effect of MLD and CMR.

Methods

Procedures and conditions

Experimental details shared much in common with those of experiment 1, including: NoSo and NoSπ phase manipulations, narrowband noise bandwidth and level, duration of observation and inter-stimulus intervals, temporal features of the signal and masker, threshold estimation procedures, and stimulus presentation hardware. The signal frequency was 2000 Hz. The masker was either a single narrow band of noise centered on the 2000-Hz signal frequency (OSB) or a complex stimulus composed of the OSB plus flanking bands. The number of flanking bands was either two (centered on 1429 and 2800 Hz) or eight (centered on 521, 729, 1020, 1429, 2800, 3920, 5488, and 7683 Hz). Each masker was composed of 218 points. When played at 24 414 Hz, this resulted in a 10.7-s sample that repeated seamlessly.

Listeners

There were six listeners, four females and two males. Listeners had audiometric thresholds that were better then 20 dB HL at octave frequencies from 250 to 8000 Hz (ANSI, 2004). Listener age ranged between 24 and 51 yr. All listeners had previously completed both CMR and MLD experiments, including two listeners from experiment 1. No additional practice was provided.

Results and discussion

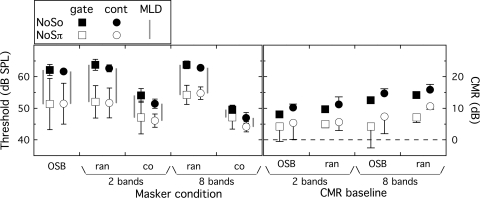

The masked thresholds of individual listeners are shown in Table TABLE II.. Mean masked thresholds are shown in the left panel of Fig. 2 and derived CMR values are shown in the right panel of Fig. 2. As in Fig. 1, CMRs for the two levels of the gating variable are differentiated both in terms of symbol (circles for continuous noise and squares for gated noise), and in terms of axis offset (continuous noise CMRs are offset to the right of gated noise CMRs). The CMR data were analyzed by performing a four-way repeated measures ANOVA, with factors of band number (two or eight), signal phase (So or Sπ), masker gating (continuous or gated), and CMR baseline (OSB or random noise). This analysis indicated significantly larger CMR for eight than two bands (F1,5 = 262; p < 001), significantly larger CMR for So than Sπ (F1,5 = 25; p = 0.004), and significantly larger CMR for continuous than gated noise (F1,5 = 13.2; p = 0.015). The main effect of baseline was not significant (F1,5 = 3.4; p = 0.12). The only interaction that reached significance was the two-way interaction between number of bands and signal phase (F1,5 = 35.1; p = 0.002). This interaction was due to the fact that the increase in CMR from two to eight bands was greater for the NoSo than NoSπ condition.

Table 2.

Individual data, along with means and standard deviations, for experiment 2.

| Gated | Continuous | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NoSo | NoSπ | NoSo | NoSπ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| OSB | 2 co | 2 ran | 8 co | 8 ran | OSB | 2 co | 2 ran | 8 co | 8 ran | OSB | 2 co | 2 ran | 8 co | 8 ran | OSB | 2 co | 2 ran | 8 co | 8 ran | ||||

| L1 | 60.2 | 52.4 | 62.2 | 47.7 | 62.4 | 41.0 | 40.1 | 45.7 | 41.1 | 48.8 | 61.3 | 49.9 | 62.9 | 45.8 | 62.4 | 41.2 | 43.7 | 45.2 | 42.0 | 52.9 | |||

| L2 | 60.3 | 51.8 | 61.9 | 49.8 | 64.3 | 43.1 | 42.7 | 46.3 | 46.9 | 53.3 | 61.6 | 52.0 | 61.8 | 47.2 | 61.7 | 45.6 | 45.0 | 48.7 | 43.6 | 53.8 | |||

| L3 | 61.9 | 54.0 | 64.0 | 48.9 | 62.0 | 56.6 | 45.7 | 52.5 | 45.3 | 54.1 | 61.8 | 51.3 | 64.1 | 44.6 | 62.7 | 55.7 | 45.7 | 52.7 | 43.7 | 54.0 | |||

| L4 | 63.7 | 55.5 | 65.8 | 51.1 | 65.1 | 49.3 | 49.2 | 53.0 | 51.0 | 55.3 | 60.9 | 51.6 | 62.0 | 46.4 | 63.2 | 54.8 | 45.1 | 50.1 | 43.3 | 53.8 | |||

| L5 | 61.8 | 53.1 | 62.9 | 48.8 | 64.6 | 56.8 | 53.1 | 57.9 | 47.4 | 56.0 | 62.8 | 53.9 | 61.4 | 49.2 | 62.7 | 56.3 | 47.5 | 55.3 | 46.1 | 55.8 | |||

| L6 | 64.7 | 57.5 | 65.8 | 51.3 | 64.0 | 61.1 | 51.8 | 56.8 | 50.9 | 57.8 | 61.6 | 50.0 | 63.8 | 48.3 | 64.2 | 55.3 | 49.6 | 58.2 | 46.1 | 58.4 | |||

| Mean | 62.1 | 54.0 | 63.8 | 49.6 | 63.7 | 51.3 | 47.1 | 52.0 | 47.1 | 54.2 | 61. 7 | 51.4 | 62. 7 | 46.9 | 62.8 | 51.5 | 46.1 | 51.7 | 44.1 | 54.8 | |||

| SD | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 8.1 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 3.1 | 0.64 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 6.4 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 1.6 | 2.0 | |||

Figure 2.

Mean results for experiment 2 (2000-Hz signal). In the left panel, mean thresholds are plotted as a function of masker condition. In the right panel, the mean CMR is plotted as a function of the baseline used to compute masking release. Labeling conventions for stimulus condition, phase, gating, and error bars follow those in Fig. 1.

A similarity between the results of this experiment (2000-Hz signal) and experiment 1 (700-Hz signal) was that CMR was smaller for the Sπ signal than the So signal. Another similarity was that there was no significant main effect of masking release baseline. A divergent result was that in experiment 2, the CMR was smaller for NoSπ than NoSo by about the same amount for the gated and continuous maskers, whereas in experiment 1, the NoSπ CMR was particularly diminished with respect to the NoSo CMR for the continuous masker. A related divergent result was that in experiment 1, there was no main effect of gating, but a significant interaction between gating and phase reflected the fact that CMR was larger for continuous than gated noise for NoSo but not for NoSπ; in experiment 2, however, the main effect of gating was significant, with no interaction between gating and phase.

The results of experiment 2 indicated that the growth of CMR with increasing number of flanking bands (from two to eight) was greater for NoSo than NoSπ. This result is not consistent with an additive effect for the MLD and CMR. It is possible that the smaller NoSπ CMR and the relatively small band number effect for NoSπ are both related to a common underlying factor. As noted by Bos and de Boer (1966), the random envelope fluctuations of narrowband noise maskers “severely hamper” monaural signal detection, perhaps because such envelope fluctuations may be difficult to distinguish from cues associated with an added signal. In monaural and NoSo conditions, a comodulated band provides a representation of the masker envelope that could be used to help separate a signal from the ongoing fluctuations of the masker. Increasing flanking-band number would increase the number of estimators of masker envelope. This could improve the quality of the estimate of the masker envelope, although there is an evidence of diminishing returns on increasing flanking-band number beyond two (Hall et al., 1990). The situation is somewhat different for NoSπ stimulation. Here, even in the absence of flanking bands, interaural difference cues are available to aid separation of the masker from the signal. Psychophysical studies on humans suggest that these cues are related to temporal fine structure and envelope at low-frequency but are restricted to temporal envelope at the relatively high-frequency of 2000 Hz used in experiment 2 (e.g., Klump and Eady, 1956; Zwislocki and Feldman, 1956; Yost and Hafter, 1987). The addition of comodulated flanking bands provides additional potential cues that might aid the differentiation of signal and masker, but their impact may be relatively small due to the fact that partially redundant information to aid signal∕noise differentiation is already available even in the NoSπ baseline conditions. This could help account for the finding that CMR was smaller for NoSπ than for NoSo and that the effect of increasing band number was likewise smaller.

Previous studies have indicated relatively large individual differences in the MLD obtained for high-frequency signals in narrowband noise maskers, due mainly to variability in the NoSπ threshold (Bernstein et al., 1998; Buss et al., 2007). Inspection of Fig. 2 reveals that the present study replicated the finding of large inter-listener variability in the MLD for the OSB baseline condition. The mean MLD was approximately 10 dB but ranged between about 4 and 20 dB. Other studies examining individual differences in the MLD for high-frequency signals have also found a large range for the MLD. For example, Bernstein et al. (1998) using a signal frequency of 4000 Hz and noise bandwidth of 50 Hz found an average MLD of approximately 6 dB and a range of approximately 2–14 dB. Buss et al. (2007), using a signal frequency of 2000 Hz and noise bandwidth of 24 Hz, found an average MLD of approximately 8 dB and a range of approximately 2–18 dB. Figure 2 also indicates that the average MLD was quite small for the condition where eight comodulated bands were present, averaging less than 3 dB. Note that this finding of a small MLD in the eight-band condition is not in line with additive MLD and CMR effects and that, again, this finding may be related to the redundancy of the envelope information. Specifically, it can be argued that the envelope cues available in the NoSo eight-band comodulated condition were only slightly augmented by the interaural cues available in the NoSπ eight-band comodulated condition. Schooneveldt and Moore (1989) also found that combined MLD and CMR effects were relatively small at the high stimulus frequency of 4000 Hz and pointed out that this could be related to redundant envelope cues across the MLD and CMR conditions. Inspection of Table TABLE II. indicates that the listeners with the lowest NoSπ thresholds in the OSB conditions (L1 and L2) had little or no binaural CMR (OSB reference) for either the continuous or the gated noise. Conversely, listeners with relatively poor NoSπ OSB thresholds generally had relatively large binaural CMRs. This trend is similar to that noted in experiment 1, and again may be related to relatively little room for improvement when the OSB threshold is very good. Correlations were not performed because of the small number of listeners in this experiment.

Another trend apparent in Fig. 2 concerns the MLDs for two versus eight flanking bands for the random noise masker. Specifically, the MLDs in the random noise case are smaller for eight than two flanking bands, due to relatively high NoSπ thresholds. Note that such an effect could not be related to signal spread of excitation because the eight-band and two-band maskers were identical with respect to the two random bands most proximal to the OSB. Repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted to explore the possible effect of band number for the random band conditions, with factors of gating and band number. Separate analyses were conducted for the MLD and for the NoSπ thresholds. For the MLD, the effects of gating (F1,5 = 5.6; p = 0.064) and band number (F1,5 = 5.1; p = 0.073) did not reach statistical significance. The interaction between gating and band number also failed to reach statistical significance (F1,5 = 0.36; p = 0.57). Similarly, for the NoSπ threshold, the effects of gating (F1,5 = 0.03; p = 0.87), band number (F1,5 = 5.67; p = 0.063), and the interaction between gating and band number (F1,5 = 0.85; p = 0.40) did not reach statistical significance.

Epp and Verhey (2009a) also reported data for a relatively high-frequency signal (3000 Hz). Similar to their results for a 700-Hz signal, they found CMR and MLD effects to be additive. It is not straightforward to compare their results to the present results because (1) their conditions using narrow bands of Gaussian masking noise showed only small MLDs, averaging less than 5 dB; (2) their conditions that yielded larger MLDs used the transposition method of van de Par and Kohlrausch (1997). It is possible that combined effects for CMR and MLD are different for the Gaussian noise masker used here than for the transposed noise masker used by Epp and Verhey (2009a).

GENERAL DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The results of experiment 1 indicated that CMR for a 700-Hz signal, using either the OSB or random noise baseline, was smaller for NoSπ than NoSo stimulation, particularly when the masker was continuous. Compared to previous studies using noise bands with narrower frequency spacing, the present results indicated larger and more reliable binaural CMRs for the OSB baseline. This may be the case because the wider band spacing used here allows better use of off-frequency cues for binaural detection (van de Par and Kohlrausch, 1999; Breebaart et al., 2001).

Experiment 2 used a signal frequency of 2000 Hz, adding the variable of number of flanking bands. The results of this experiment again showed smaller CMR for NoSπ than NoSo stimulation for both continuous and gated masking noise. The greater increase in CMR with increasing flanking-band number for NoSo than NoSπ was not consistent with an additive effect for the MLD and CMR.

Some of the present results can be compared with those of Epp and Verhey (2009a) whereas other comparisons are more difficult. The present continuous noise conditions cannot be compared across studies because Epp and Verhey examined only gated conditions. Furthermore, the high-frequency results are not easily comparable between studies because Epp and Verhey (2009a) did not find large MLDs at high-frequency for their Gaussian noise maskers, and the present study did not examine the transposed noise conditions used in their study. The conditions involving gated maskers at the 700-Hz signal frequency region were the most similar between studies. Epp and Verhey reported that the NoSo and NoSπ CMRs were the same in these conditions for the random-masker baseline, but that the NoSπ CMR was much smaller than the NoSo CMR for the OSB baseline. The present study found that the NoSπ CMR for gated noise was smaller (by 2–3 dB on average) than the NoSo CMR for both the random-masker and OSB baselines. Thus, in terms of directly comparable conditions between the two studies, the Epp and Verhey study supported a conclusion that CMR and MLD effects are additive for gated maskers in the random noise baseline, whereas the present study indicated that the effects were less than additive.

The results of the present study showed that CMR and MLD effects can fall far short of being additive using either the OSB or random noise baseline. This was evident in the continuous noise conditions at 700 Hz, where the NoSπ CMR was about half the magnitude of the NoSo CMR for the random noise baseline (and smaller still for the OSB baseline). The data for the 2000-Hz signal also showed consistently smaller CMRs for NoSπ than NoSo in both gated and continuous noise, and for both the random noise and OSB baselines. These findings, along with the result that the growth of CMR with increasing number of flanking bands was greater for NoSo than NoSπ are not consistent with an additive effect for CMR and MLD.

Although the present results indicated less than additive effects for MLD and CMR, it is important to note that they do not undermine an interpretation in terms of serial processes that effectively improve the signal-to-noise ratio (Hall et al., 1988; Schooneveldt and Moore, 1989; Epp and Verhey, 2009a,b, 10). As suggested by Schooneveldt and Moore (1989), the accumulation of benefit between stages may be limited by cue redundancy. It should be noted that the improvement in NoSπ thresholds when comodulated bands are added may not require serial MLD and CMR processes. For example, Hall et al. (2006) suggested that comodulated flanking bands may be used to weight the binaural cues contributing to the MLD. Specifically, the comodulated bands serve as covariates that help to identify the masker envelope minima where the signal-to-noise ratio is most favorable and, therefore, the binaural difference cues are largest. This idea is essentially the same as Buus’ (1985) “dip listening” model of monaural CMR, but applied to binaural masking release. Regardless of the mechanism by which monaural and binaural cues are combined, the present results indicate that the magnitude of masking release observed when both types of cues are present cannot be reliably predicted as the sum of masking release magnitudes for each type of cue in isolation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Laurent Demany, Brian C. J. Moore, and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments on previous versions of this manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from NIH NIDCD, R01 DC00397.

Footnotes

It should be noted that whereas the threshold estimation procedure used by Epp and Verhey used a final step size of 1 dB, the present procedure used a final step size of 2 dB. It seems unlikely that this procedural difference would contribute to differences in the patterns of results between the two studies.

Inspection of the individual data revealed that one listener (L9) showed findings that were unique. For this listener, the presence of random No flanking bands led to Sπ thresholds that were a few decibels better than in the OSB condition. A related finding that was unique to this listener was that the Sπ CMR was larger for the OSB baseline than the random baseline, both in gated noise (where the OSB baseline CMR was 7.9 dB and the random baseline CMR was −0.2 dB) and in continuous noise (where the OSB baseline CMR was 9.1 dB and the random baseline CMR was 3.3 dB). Several weeks after completing the study, this listener was retested and showed the same data pattern. Because of the singular nature of these results, statistics were rerun excluding this listener. The pattern of statistical outcomes (in terms of the alpha level of p < 0.05) was unchanged, except that the effect of baseline went from a non-significant p < 0.09 to a significant p < 0.001 (F1,7 = 4.0), indicating a larger CMR for the random noise baseline than the OSB baseline when the data of L9 were excluded.

References

- ANSI (2004). ANSI S3.6-2004, Specification for Audiometers (American National Standards Institute, New York). [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, L. R., Trahiotis, C., and Hyde, E. L. (1998). “Inter-individual differences in binaural detection of low-frequency or high-frequency tonal signals masked by narrow-band or broadband noise,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 103, 2069–2078. 10.1121/1.421378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos, C. E., and de Boer, E. (1966). “Masking and discrimination,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 39, 708–715. 10.1121/1.1909945 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breebaart, J., van de Par, S., and Kohlrausch, A. (2001). “Binaural processing model based on contralateral inhibition. II. Dependence on spectral parameters,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 110, 1089–1104. 10.1121/1.1383298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss, E., and Hall, J. W. (2011). “Effects of non-simultaneous masking on the binaural masking level difference,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 129, 907–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss, E., Hall, J. W., and Grose, J. H. (2007). “Individual differences in the masking level difference with a narrowband masker at 500 or 2000 Hz,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 121, 411–419. 10.1121/1.2400849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buus, S. (1985). “Release from masking caused by envelope fluctuations,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 78, 1958–1965. 10.1121/1.392652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M. F., and Schubert, E. D. (1991). “Comodulation masking release and the masking-level difference,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 89, 3007–3008. 10.1121/1.400739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epp, B., and Verhey, J. L. (2009a). “Combination of masking releases for different center frequencies and masker amplitude statistics,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 126, 2479–2489. 10.1121/1.3205404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epp, B., and Verhey, J. L. (2009b). “Superposition of masking releases,” J. Comput. Neurosci. 26, 393–407. 10.1007/s10827-008-0118-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantini, D. A., Moore, B. C. J., and Schooneveldt, G. P. (1993). “Comodulation masking release as a function of type of signal, gated or continuous masking, monaural or dichotic presentation of flanking bands, and center frequency,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 93, 2106–2115. 10.1121/1.406697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J. W., Buss, E., and Grose, J. H. (2006). “Binaural comodulation masking release: Effects of masker interaural correlation,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 120, 3878–3888. 10.1121/1.2357989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J. W., Cokely, J., and Grose, J. H. (1988). “Combined monaural and binaural masking release,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 83, 1839–1845. 10.1121/1.396519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J. W., Grose, J. H., and Haggard, M. P. (1990). “Effects of flanking band proximity, number, and modulation pattern on comodulation masking release,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 87, 269–283. 10.1121/1.399294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J. W., Grose, J. H., and Hatch, D. R. (1996). “Effects of masker gating for signal detection in unmodulated and modulated bandlimited noise,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 100, 2365–2372. 10.1121/1.417946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J. W., Haggard, M. P., and Fernandes, M. A. (1984). “Detection in noise by spectro-temporal pattern analysis,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 76, 50–56. 10.1121/1.391005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch, D. R., Arné, B. C., and Hall, J. W. (1995). “Comodulation masking release (CMR): Effects of gating as a function of number of flanking bands and masker bandwidth,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 97, 3768–3774. 10.1121/1.412392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh, I. J. (1948). “Binaural summation and interaural inhibition as a function of the level of the masking noise,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 20, 205–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, R. E. (1968). Experimental Design: Procedures for the Behavioral Sciences (Wadsworth, Belmont, CA: ), pp. 179–182. [Google Scholar]

- Klump, R. G., and Eady, H. R. (1956). “Some measurements of interaural time difference thresholds,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 28, 859–860. 10.1121/1.1908493 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, H. (1971). “Transformed up-down methods in psychoacoustics,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 49, 467–477. 10.1121/1.1912375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licklider, J. C. R. (1948). “The influence of interaural phase relations upon the masking of speech by white noise,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 20, 150–159. 10.1121/1.1906358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, D., and Wright, B. A. (1992). “Temporal decline of masking and comodulation masking release,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 92, 144–156. 10.1121/1.404279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooneveldt, G. P., and Moore, B. C. J. (1987). “Comodulation masking release (CMR): Effects of signal frequency, flanking-band frequency, masker bandwidth, flanking-band level, and monotic versus dichotic presentation flanking band,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 82, 1944–1956. 10.1121/1.395639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooneveldt, G. P., and Moore, B. C. J. (1989). “Comodulation masking release (CMR) for various monaural and binaural combinations of the signal, on-frequency, and flanking bands,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 85, 262–272. 10.1121/1.397733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Par, S., and Kohlrausch, A. (1997). “A new approach to comparing binaural masking level differences at low and high frequencies,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 101, 1671–1680. 10.1121/1.418151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Par, S., and Kohlrausch, A. (1999). “Dependence of binaural masking level differences on center frequency, masker bandwidth, and interaural parameters,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 106, 1940–1947. 10.1121/1.427942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost, W. A., and Hafter, E. R. (1987). “Lateralization,” in Directional Hearing, edited by Yost W. A. and Gourevitch G.(Springer-Verlag, New York: ), pp. 49–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zwislocki, J., and Feldman, R. S. (1956). “Just noticeable differences in dichotic phase,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 28, 860–864. 10.1121/1.1908495 [DOI] [Google Scholar]