Abstract

Hypometabolism is a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and implicates a mitochondrial role in the neuropathology associated with AD. Mitochondrial amyloid-beta (Aβ) accumulation precedes extracellular Aβ deposition. In addition to increasing oxidative stress, Aβ has been shown to directly inhibit mitochondrial enzymes. Inhibition of mitochondrial enzymes as a result of oxidative damage or Aβ interaction perpetuates oxidative stress and leads to a hypometabolic state. Additionally, Aβ has also been shown to interact with cyclophilin D, a component of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, which may promote cell death. Therefore, ample evidence exists indicating that the mitochondrion plays a vital role in the pathophysiology observed in AD.

1. Introduction

The incidence of Alzheimer's disease (AD) in the US is expected to increase to as many as 13.2 million by 2050 [1]. AD pathology is characterized by the progressive accumulation of senile plaques (consisting of amyloid β-peptide, Aβ) and neurofibrillary tangles (consisting of aggregates of the microtubule-associated protein tau). Oxidative damage has been implicated to play an early role in the pathogenesis of AD [2]. In AD patients a significant decrease in energy metabolism is observed in the frontal and temporal lobes as indicated by in vivo positron emission tomography (PET) [3]. Correlated with this increase in oxidative damage and decrease in energy metabolism is a decrease in mitochondrial enzyme (cytochrome c oxidase, pyruvate dehydrogenase, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase) activity in AD patients [4–6].

Mitochondrial dysfunction has been shown to play a key role in age-related neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease [7]. Mitochondria produce the majority of ATP in cells and function to maintain Ca2+ homeostasis. Mitochondria produce ATP by coupling electron transfer to the pumping of protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane. However, electrons can escape the electron transport chain and reduce oxygen to form reactive oxygen species (ROS). Oxidative damage results from a disturbance in the ROS-antioxidant balance that favors oxidation. Oxidative damage to mitochondria may be especially relevant in neurodegenerative disease since mitochondria are regulators of both cellular metabolism and apoptosis [8].

2. Mitochondrial Enzyme Oxidative Damage and ROS Production

A hallmark of AD is hypometabolism which, importantly, precedes the clinical presentation of the disease [9, 10]. Early studies utilizing PET indicated that brain metabolism throughout the cortex in AD patients is significantly lower than cortical metabolism in normal subjects [11, 12]. Clinical data from PET studies have shown which areas of the brain are mostly affected by mild and moderate AD, such as the posterior cingulate cortex, parietotemporal cortex, and prefrontal association cortices [13]. Also decreased metabolism and synaptic loss have been shown to overlap in the frontal and middle temporal gyri [14–17].

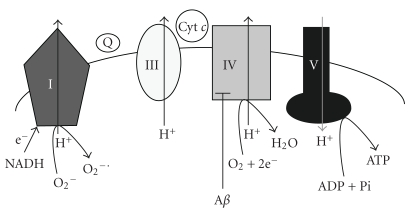

Mitochondria sustain the activity of neurons by producing ATP via the electron transport system (ETC) (Figure 1). Complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) catalyzes the transfer of two electrons from NADH to coenzyme Q [18]. Complex III (ubiquinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase) catalyzes the transfer of electrons from coenzyme Q to cytochrome c. Complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) reduces oxygen to water. As electrons are transported through complexes I, III, and IV, protons are pumped into the inner membrane space, generating an electrochemical gradient. This store of energy is used to generate ATP via the ATP synthase. ROS production is linked to membrane potential (Δψ) such that a high Δψ promotes increased ROS production [9]. High Δψ results in altered redox potential of ETC carriers and an increase in the half-life time of ubisemiquinone leading to increased ROS production. Also, any damage to components of the ETC could lead to a stalling of reduced intermediates of the ETC which would increase the probability of an electron slipping and reducing O2 to form ROS.

Figure 1.

The relationship between amyloid-β (Aβ), mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC), and superoxide (O2 −∙) formation. As electrons are transferred through complexes I, III, and IV, protons are pumped into the inner membrane space, generating an electrochemical gradient. The energy stored is used to generate ATP via complex V (ATP synthase). Damage to components of the ETC can lead to a stalling of reduced intermediates which increases the probability of electrons slipping and reducing O2 to form superoxide. Aβ has been shown to directly inhibit complex IV which would lead to bioenergetic impairment and increased formation of reactive oxygen species.

Postmortem assessment of human AD brains has revealed increased levels of oxidative damage which coincides with impairments in metabolism and Aβ processing [19]. Since mitochondria are the primary source of cellular ROS production, it is at least conceivable that as an organism ages mitochondrial enzymes would be especially vulnerable to oxidative damage. Damage to mitochondrial enzymes would cause defects in electron transport and promote ROS production. Redox proteomic analysis has revealed that a number of mitochondrial proteins are oxidatively modified including VDAC, aconitase, GAPDH, and lactate dehydrogenase in AD patients [20].

The most documented reduction of mitochondrial enzyme activity in AD is the activity of complex IV [5, 21–23]. Since peroxidative damage of cardiolipin in mitochondrial membranes has been shown to affect the activity of complex IV; ROS-mediated damage of membranes is postulated to partly be responsible for Aβ inhibition of complex IV [24]. However, since antioxidants fail to fully protect mitochondria from amyloid beta toxicity, it has been hypothesized that Aβ itself directly inhibits mitochondrial enzymes [24]. The Aβ25–35 fragment has been shown to selectively inhibit complex IV [25]. The Aβ25–35 fragment retains the residues required for aggregation and undergoes aggregation more rapidly than full-length Aβ. In another study, both the full-length Aβ1–42 and Aβ25–35 fragment resulted in inhibition of complex IV, and Aβ25–35 raised the Km of complex IV for reduced cytochrome c [26]. The authors concluded that Aβ may act as an inhibitor of one of the cytochrome c binding sites of complex IV.

Additionally, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase has been shown to have reduced activity in AD [27]. Recently we reported an age-dependent decrease in NADH-linked, complex I- driven respiration rate and an increase in mitochondrial ROS production in aged dogs [28]. Therefore, it is evident that cumulative oxidative damage over the lifespan of an organism can affect mitochondrial efficiency and leave neurons susceptible to cell death.

3. Oxidation of Mitochondrial DNA

It has been hypothesized that ongoing oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) may be the underlying mechanism for cellular senescence [29]. Since mtDNA repair mechanisms are limited and because mtDNA is situated in close proximity to the site of ROS production, mtDNA is more vulnerable to oxidative damage than nuclear DNA [30]. With age, oxidation of mtDNA increases compared to nuclear DNA leading to an age-dependent accumulation of mtDNA mutations [31]. One recent study found that somatic mtDNA control region mutations are elevated in AD patients [32]. These mutations would lead to an overall reduction in mtDNA copy number which would result in a decrease in oxidative phosphorylation. In addition, a mutation that affects L-strand transcription was also discovered. This mutation inhibits complex I respiration which leads to increased ROS production, decreased membrane potential, and subsequent Ca2+ deregulation. The effects of these mutations may lead to opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and subsequent neuronal death. Other evidence that oxidative damage to mtDNA could contribute to AD pathology is the observation that a risk factor for late-onset AD is a maternal history of AD [33]. This observation could be related to the fact that mitochondrial DNA is maternally inherited.

4. Amyloid-β: Cause or Effect of Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Aβ has been shown to accumulate in mitochondria from AD patients [34]. Altered processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP) which results in deposition of neurotoxic forms of Aβ, known as the amyloid hypothesis of AD, is believed to play a central role in the development of AD [35]. This hypothesis is supported by studies which show that immunization against Aβ decreases amyloid levels and improves cognition in APP transgenic mice [36–38].

Intracellular and mitochondrial accumulation of Aβ likely precedes extracellular Aβ deposition [34, 39, 40]. Recently Aβ has been shown to accumulate early (as young as 4 mo) and specifically in synaptic mitochondria [40]. We have shown that synaptic mitochondria have high levels of cyclophilin D (CypD) which makes them more susceptible to changes in synaptic Ca2+ [41]. Importantly, synaptic Ca2+ homeostasis is regulated by synaptic mitochondria, and susceptibility to Ca2+ would disrupt synaptic function [42]. CypD is a peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase located in the matrix and is a component of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP). CypD translocates from the matrix to the mPTP and interacts with the adenine nucleotide translocase of the inner membrane to promote pore formation. Opening of the mPTP leads to a collapse in Δψ and release of proapoptotic molecules (i.e., cytochrome C, Smac/Diablo, and apoptosis-inducing factor). A reduction in Δψ would lead to bioenergetic failure and subsequent synaptic failure ending in neuronal death. In fact, mitochondrial Aβ has been shown to interact with CypD, and CypD deficiency attenuates Aβ-induced mitochondrial stress [43]. This may indicate that because synaptic mitochondria have increased levels of, (i) cyclophilin D and (ii) Aβ, they are important in the pathogenesis of AD.

Mitochondrial dynamics are altered in AD patients, and mitochondrial fission has been shown to be more prevalent than fusion in AD [44]. This observation is supported by evidence indicating that the number of mitochondria is decreased in AD which corresponds with an increase in mitochondrial size [45]. APP overexpression, through Aβ production, was shown to increase protein levels of proteins associated with fission (Fis1) and decreased protein levels of those involved in fusion (dynamin-like protein and OPA1) [46]. In addition Aβ has been shown to cause oxidative damage to Drp1 which resulted in mitochondrial fission [47]. Altered mitochondrial dynamics may result in decreased mtDNA copy number which would result in defects in mitochondrial electron transport activity.

While the exact mechanism underlying APP mismetabolism is unclear, it appears that Aβ production itself is least partially induced by oxidative stress [48]. Aβ can function both as an antioxidant and pro-oxidant [49]. At low concentrations (low-nanomolar) Aβ remains monomeric and can function as an antioxidant. However, at higher concentrations, aggregation of Aβ produces H2O2. Aβ-induced oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction has been demonstrated in AD models [50, 51]. In APP mutant mice that display increased levels of Aβ, cognition-related brain regions have altered glucose metabolism [52]. Furthermore, mitochondria-targeted antioxidants have been shown to attenuate Aβ-induced mitochondrial dysfunction [53]. Taken together, mitochondrial-induced oxidative stress may induce the production of Aβ, which itself increases oxidative stress and impairs mitochondrial function and may provide a feed-forward loop that increases Aβ levels.

5. Conclusion

In summary, since cerebral hypometabolism and inhibition of mitochondrial function have been demonstrated in AD, mitochondria likely play a role in AD neuropathology. Aβ has been shown to both directly and indirectly impair mitochondrial function. Impairment of mitochondrial function increases ROS production which may further damage mitochondrial enzymes and mtDNA. Likely, mitochondrial dysfunction exacerbates the production of ROS and Aβ, which provides a feed-forward mechanism ultimately leading to AD pathology.

References

- 1.Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Archives of Neurology. 2003;60(8):1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith MA, Rottkamp CA, Nunomura A, Raina AK, Perry G. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2000;1502(1):139–144. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattson MP. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2004;430(7000):631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature02621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibson GE, Zhang H, Sheu KFR, et al. α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase in Alzheimer brains bearing the APP670/671 mutation. Annals of Neurology. 1998;44(4):676–681. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castellani R, Hirai K, Aliev G, et al. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2002;70(3):357–360. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blass JP. Brain metabolism and brain disease: is metabolic deficiency the proximate cause of Alzheimer dementia? Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2001;66(5):851–856. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1998;1366(1-2):211–223. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan PG, Rabchevsky AG, Waldmeier PC, Springer JE. Mitochondrial permeability transition in CNS trauma: cause or effect of neuronal cell death? Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2005;79(1-2):231–239. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan PG, Brown MR. Mitochondrial aging and dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2005;29(3):407–410. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blass JP, Sheu RKF, Gibson GE. Inherent abnormalities in energy metabolism in Alzheimer disease: interaction with cerebrovascular compromise. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2000;903:204–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Leon MJ, Ferris SH, George AE, et al. Positron emission tomographic studies of aging and Alzheimer disease. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 1983;4(3):568–571. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koss E, Friedland RP, Ober BA, Jagust WJ. Differences in lateral hemispheric asymmetries of glucose utilization between early- and late-onset Alzheimer-type dementia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142(5):638–640. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.5.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herholz K, Salmon E, Perani D, et al. Discrimination between Alzheimer dementia and controls by automated analysis of multicenter FDG PET. NeuroImage. 2002;17(1):302–316. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheff SW, Price DA. Alzheimer’s disease-related synapse loss in the cingulate cortex. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2001;3(5):495–505. doi: 10.3233/jad-2001-3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scheff SW, Price DA. Synapse loss in the temporal lobe in Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of Neurology. 1993;33(2):190–199. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith GS, De Leon MJ, George AE, et al. Topography of cross-sectional and longitudinal glucose metabolic deficits in Alzheimer’s disease: pathophysiologic implications. Archives of Neurology. 1992;49(11):1142–1150. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530350056020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minoshima S, Giordani B, Berent S, Frey KA, Foster NL, Kuhl DE. Metabolic reduction in the posterior cingulate cortex in very early Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of Neurology. 1997;42(1):85–94. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholls DG. Mitochondrial function and dysfunction in the cell: its relevance to aging and aging-related disease. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2002;34(11):1372–1381. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mangialasche F, Polidori MC, Monastero R, et al. Biomarkers of oxidative and nitrosative damage in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Ageing Research Reviews. 2009;8(4):285–305. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sultana R, Butterfield DA. Oxidatively modified, mitochondria-relevant brain proteins in subjects with Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2009;41(5):441–446. doi: 10.1007/s10863-009-9241-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kish SJ, Bergeron C, Rajput A, et al. Brain cytochrome oxidase in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1992;59(2):776–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parker WD, Filley CM, Parks JK. Cytochrome oxidase deficiency in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1990;40(8):1302–1303. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.8.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maurer I, Zierz S, Möller HJ. A selective defect of cytochrome c oxidase is present in brain of Alzheimer disease patients. Neurobiology of Aging. 2000;21(3):455–462. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Su B, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. Insights into amyloid-β-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2007;43(12):1569–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canevari L, Clark JB, Bates TE. β-Amyloid fragment 25-35 selectively decreases complex IV activity in isolated mitochondria. FEBS Letters. 1999;457(1):131–134. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casley CS, Canevari L, Land JM, Clark JB, Sharpe MA. β-Amyloid inhibits integrated mitochondrial respiration and key enzyme activities. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2002;80(1):91–100. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorbi S, Bird ED, Blass JP. Decreased pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity in Huntington and Alzheimer brain. Annals of Neurology. 1983;13(1):72–78. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Head E, Nukala VN, Fenoglio KA, Muggenburg BA, Cotman CW, Sullivan PG. Effects of age, dietary, and behavioral enrichment on brain mitochondria in a canine model of human aging. Experimental Neurology. 2009;220(1):171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miquel J. An update on the mitochondrial-DNA mutation hypothesis of cell aging. Mutation Research. 1992;275(3-6):209–216. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(92)90024-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imam SZ, Karahalil B, Hogue BA, Souza-Pinto NC, Bohr VA. Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA-repair capacity of various brain regions in mouse is altered in an age-dependent manner. Neurobiology of Aging. 2006;27(8):1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sastre J, Pallardó FV, García De La Asunción J, Viña J. Mitochondria, oxidative stress and aging. Free Radical Research. 2000;32(3):189–198. doi: 10.1080/10715760000300201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coskun PE, Wyrembak J, Derbereva O, et al. Systemic mitochondrial dysfunction and the etiology of Alzheimer's disease and down syndrome dementia. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2010;20(supplement 2):S293–S310. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosconi L, Berti V, Swerdlow RH, Pupi A, Duara R, de Leon M. Maternal transmission of Alzheimer’s disease: prodromal metabolic phenotype and the search for genes. Human Genomics. 2010;4(3):170–193. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-4-3-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manczak M, Anekonda TS, Henson E, Park BS, Quinn J, Reddy PH. Mitochondria are a direct site of Aβ accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease neurons: implications for free radical generation and oxidative damage in disease progression. Human Molecular Genetics. 2006;15(9):1437–1449. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297(5580):353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janus C, Pearson J, McLaurin J, et al. Aβ peptide immunization reduces behavioural impairment and plaques in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2000;408(6815):979–982. doi: 10.1038/35050110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan D, Diamond DM, Gottschall PE, et al. A β peptide vaccination prevents memory loss in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2000;408(6815):982–985. doi: 10.1038/35050116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilcock DM, Rojiani A, Rosenthal A, et al. Passive immunotherapy against Aβ in aged APP-transgenic mice reverses cognitive deficits and depletes parenchymal amyloid deposits in spite of increased vascular amyloid and microhemorrhage. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2004;1(1):p. 24. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wirths O, Multhaup G, Czech C, et al. Intraneuronal Aβ accumulation precedes plaque formation in β-amyloid precursor protein and presenilin-1 double-transgenic mice. Neuroscience Letters. 2001;306(1-2):116–120. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01876-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du H, Guo L, Yan S, Sosunov AA, McKhann GM, Yan SS. Early deficits in synaptic mitochondria in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(43):18670–18675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006586107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naga KK, Sullivan PG, Geddes JW. High cyclophilin D content of synaptic mitochondria results in increased vulnerability to permeability transition. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(28):7469–7475. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0646-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galindo MF, Ikuta I, Zhu X, Casadesus G, Jordán J. Mitochondrial biology in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2010;114(4):933–945. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Du H, Guo L, Fang F, et al. Cyclophilin D deficiency attenuates mitochondrial and neuronal perturbation and ameliorates learning and memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Medicine. 2008;14(10):1097–1105. doi: 10.1038/nm.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonda DJ, Wang X, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. Mitochondrial dynamics in alzheimers disease: opportunities for future treatment strategies. Drugs and Aging. 2010;27(3):181–192. doi: 10.2165/11532140-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirai K, Aliev G, Nunomura A, et al. Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21(9):3017–3023. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-03017.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, Su B, Siedlak SL, et al. Amyloid-β overproduction causes abnormal mitochondrial dynamics via differential modulation of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(49):19318–19323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804871105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cho DH, Nakamura T, Fang J, et al. β-Amyloid-related mitochondrial fission and neuronal injury. Science. 2009;324(5923):102–105. doi: 10.1126/science.1171091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Recuero M, Muñoz T, Aldudo J, Subías M, Bullido MJ, Valdivieso F. A free radical-generating system regulates APP metabolism/processing. FEBS Letters. 2010;584(22):4611–4618. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kontush A. Amyloid-β: an antioxidant that becomes a pro-oxidant and critically contributes to Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2001;31(9):1120–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rhein V, Baysang G, Rao S, et al. Amyloid-beta leads to impaired cellular respiration, energy production and mitochondrial electron chain complex activities in human neuroblastoma cells. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 2009;29(6-7):1063–1071. doi: 10.1007/s10571-009-9398-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yao J, Irwin RW, Zhao L, Nilsen J, Hamilton RT, Brinton RD. Mitochondrial bioenergetic deficit precedes Alzheimer’s pathology in female mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(34):14670–14675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903563106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dodart JC, Mathis C, Bales KR, Paul SM, Ungerer A. Early regional cerebral glucose hypometabolism in transgenic mice overexpressing the V717F β-amyloid precursor protein. Neuroscience Letters. 1999;277(1):49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00847-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manczak M, Mao P, Calkins MJ, et al. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants protect against amyloid-β toxicity in Alzheimer's disease neurons. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2010;20(supplement 2):S609–S631. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]