Abstract

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is associated with reduced activity of placental amino acid transport systems β and A. Whether this phenotype is maintained in fetal cells outside the placenta is unknown. In IUGR cord blood TNF-α concentrations are raised, potentially influencing amino acid transport in fetal cells. We used fetal T lymphocytes as a model to study systems β and A amino acid transporters in IUGR compared to normal pregnancy. We also studied the effect of TNF-α on amino acid transporter activity. In fetal lymphocytes from IUGR pregnancies, taurine transporter (TAUT) mRNA expression encoding system β transporter was reduced but there was no change in system β activity. No significant differences were observed in system A mRNA expression (encoding SNAT1 and SNAT2) or system A activity between the two groups. After 24h or 48h TNF-α treatment, fetal T lymphocytes from normal pregnancies showed no significant change in system A or system β activity, though cell viability was compromised. This study represents the first characterisation of amino acid transport in a fetal cell outside of the placenta in IUGR. We conclude that the reduced amino acid transporter activity found in placenta in IUGR is not a feature of all fetal cells.

Keywords: Amino acid transport, fetal lymphocytes, intrauterine growth restriction, TNF-α, placenta

INTRODUCTION

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) occurs when a fetus fails to achieve its expected growth potential and may complicate about 5% of pregnancies (1). The short- and long-term consequences include perinatal morbidity with an increased risk of a ‘cerebral insult’ and neurodevelopmental impairments in later childhood (2). In IUGR there is a reduction in cord plasma concentration of amino acids including essential amino acids (3, 4), underscored by a reduced activity of certain amino acid transport systems in the syncytiotrophoblast of human placenta (5).

Amino acid transfer across the placenta is mediated by transporters in the maternal-facing microvillous plasma membrane (MVM) and fetal-facing basal plasma membrane (BM) of the syncytiotrophoblast (6). Plasma amino acid concentrations are higher in the fetus than in the mother, in keeping with active transport systems in MVM and BM. In IUGR, the activities of a range of amino acid transporters in MVM and BM are reduced (5). These include system A transporter in MVM (7-9), system L transporter in MVM and BM (10), system y+L transporter in BM (10) and system β transporter in MVM (11). Furthermore, stable isotope studies have shown that placental supply of leucine and phenylalanine exceeds fetal demand for protein synthesis by only a small amount suggesting a narrow safety margin for placental transfer of these essential amino acids (12). Thus, reduced amino acid placental transfer in IUGR has the potential to directly limit fetal growth (5, 13).

The basis for this decreased placental amino acid transport activity is not clearly understood. It may have a genetic basis or may be secondary to an alteration in the metabolic and /or endocrine milieu of the mother or the fetus. If there is a genetic element to the decreased placental amino acid transport in IUGR, then a similar decrease could be proposed in other fetal cells reducing the capacity for cell division and subsequent growth. Metabolic or endocrine perturbations, such as the reduced amino acid concentrations in fetal plasma in IUGR could result in adaptive up-regulation of transporters in fetal cells (14). Furthermore, in IUGR the increase in circulating plasma TNF-α concentration (15) may influence amino acid transporter activity (16). These situations raise the possibility that changes in amino acid transport could occur in fetal cells outside the placenta, thereby contributing to the pathophysiology of IUGR. This concept is also relevant to understanding the sequelae after such an infant is born, since the potential for catch-up growth and development postnatally may be influenced by alterations that have taken place to these amino acid transporters in utero.

We have recently developed a technique to isolate pure, viable fetal T lymphocytes from cord blood as an easily accessible fetal cell type, and have demonstrated system β-mediated taurine transport by these cells (17). Our observations here also indicate these cells express the ubiquitous amino acid transporter System A, which transports neutral amino acids with short or linear side chains including alanine, serine and glycine (18). System A has the unique ability to transport N-methylated amino acid α-(methylamino)isobutyric acid (MeAIB) (18), a substrate widely used to study system A activity in placenta. System A activity is mediated by three highly homologous isoforms of the sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter (SNAT) family, namely SNAT1, SNAT2 and SNAT4 which are encoded by the genes SLC38A1, SLC38A2 and SLC38A4 respectively (18).

We hypothesised that the activity and expression of amino acid transporter systems in fetal cells outside of the placenta would be reduced in IUGR as compared to normal pregnancies. The aims of this study were firstly, to examine mRNA expression of TAUT and SNAT isoforms in fetal lymphocytes, comparing IUGR with appropriate-for-gestational age (AGA) infants. Secondly, to determine whether the transport activity of systems β and A was altered in fetal T lymphocytes obtained from cord blood of infants born at term with IUGR as compared with that in lymphocytes from AGA infants. Thirdly, to investigate the cytokine-mediated effects of TNF-α on system β and system A transporter activity in fetal T lymphocytes from normal pregnancy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue acquisition

All cord blood or placental tissue samples were obtained with written informed consent as approved by the Central Manchester Local Research Ethics Committee. Placentas were obtained following vaginal delivery or caesarean section from normal pregnancies (AGA) or IUGR pregnancies at term (37-42 weeks). IUGR was defined as an individualised birth ratio (IBR) <6th centile, with or without a reduction in growth velocity on serial growth scans or changes in umbilical artery blood flow as determined by Doppler studies. By using IBR, birthweight for gestational age was corrected for the confounding variables of maternal height and weight, ethnic origin, parity and infant sex (19). Babies with chromosomal and congenital anomalies and pregnancies complicated by other pathologies were excluded.

Cord blood from the chorionic vessels (10-60ml) was obtained within 15min of delivery of the placenta as 10ml aliquots using a 21G needle and placed in 25ml sterile universal bottles with 400 units sodium heparin without preservative (CP Pharmaceuticals, Wrexham, UK).

Isolation of fetal T lymphocytes

Pure and viable fetal T lymphocytes were obtained from cord blood as described previously (17). Briefly, fetal T lymphocytes were isolated by two rounds of density gradient centrifugation followed by immunomagnetic bead depletion of contaminating cells. The purity of the T lymphocyte isolates was determined by flow cytometry using CD3 as a T cell marker (17). T lymphocyte viability was assessed by 0.1% trypan blue exclusion (17).

System β activity

After isolation, fetal T lymphocytes were suspended in Tyrode’s buffer (in mM: 135 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2.6H2O, 10 HEPES and 5.6 glucose, pH 7.4) containing 0.1% BSA. System β activity, taken as the uptake of 0.2μM 3H-taurine over 15min, was measured as described previously (17) using 30μl cells (3 – 5 × 106 cells). The cells were pre-incubated in Tyrode’s buffer for 30 min prior to amino acid uptake, to reduce intracellular concentration of amino acids and avoid trans-inhibition.

System A activity

The procedure for the measurement of system A activity was similar to that for system β (17), measured as the uptake of 14C-MeAIB. 30μl cells (3 – 5 × 106 cells) were mixed with 20μl Tyrodes/0.1% BSA containing 500μM 14C-MeAIB to give an incubation volume of 50μl containing 200μM 14C-MeAIB.

TAUT mRNA expression

Expression of TAUT mRNA in fetal T lymphocytes was quantified by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) using intercalation of SYBR Green with normalization to term placenta as internal calibrator as described previously (17). Amplification capacity was confirmed in all samples using β-actin primers, as detailed previously (17).

SNAT mRNA expression

SLC38A1 (SNAT1), SLC38A2 (SNAT2) and SLC38A4 (SNAT4) mRNA expression in fetal T lymphocytes was quantified as described above using primers that had been previously validated and confirmed to be specific for each of the SNAT isoforms (20). Electrophoresis of all qPCR products on agarose gel (2%) in the presence of ethidium bromide (0.5μg/ml) was undertaken to confirm primer specificity, inferred by the visualisation of a single amplicon of the predicted size.

TNF-α treatment of T lymphocytes

Isolated T lymphocytes from normal, term pregnancies were suspended in culture media (RPMI 1640 Glutamax with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100U/ml penicillin, 100μg/ml streptomycin: all from Invitrogen, Paisley, Scotland). Viability and count was determined by trypan blue exclusion and the cells were then split into different flasks at a concentration of 0.5 – 1.0 × 106 cells/ml (5-6 × 106 cells/flask). The cells were cultured with 0, 20 and 50ng/ml recombinant human TNF-α (Invitrogen) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 for 24 or 48h respectively. After culture, the cells were washed with PBS/0.1% BSA and suspended in Tyrode’s /0.1% BSA. The viability and number of cells were determined and uptakes performed for systems β and A (10 min incubation) as detailed above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism version 4.01 (GraphPad Software, San Antonio, CA). The clinical characteristics, blood volume, number of T lymphocytes recovered and cell viability of term AGA and IUGR babies are presented as mean ± SEM. For the time courses, 3H-taurine uptake by system β and 14C-MeAIB uptake by system A, is presented as mean ± SEM. Linear regression analysis was applied to determine linearity of uptake over 15 min. Relative mRNA expression is presented as median, 25th and 75th centile and range and was analysed with the Mann-Whitney test. For TNF-α treatment of cells, T lymphocyte viability and uptake of radiolabelled substrates between different treatment groups with time was analysed by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post-test where there was a significant difference. For all analyses, n = number of placentas with a value of p<0.05 considered significant.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of AGA and IUGR babies

There was a significant difference in the birthweight of AGA and IUGR babies (Table 1). There were no significant differences in the gestational age of the pregnancies, the sex or the mode of delivery of the babies. Seven of the eleven AGA babies and seven of the eight IUGR babies were born to Caucasian parents.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of AGA and IUGR groups used to isolate fetal T lymphocytes in this study

| AGA (n = 11) | IUGR (n = 8) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gestation (days) | 274 ± 3 | 270 ± 4 |

| Birthweight (g) | 3579 ± 152 | 2165 ± 179* |

| Sex | M = 7; F = 4 | M = 4; F = 4 |

| Mode of Delivery | VD = 9; CS = 2 | VD = 4; CS = 3; Ve = 1 |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

p< 0.001 v AGA (two-tailed t test). M = male, F = female, VD = vaginal delivery, CS = caesarean section, Ve = ventouse delivery.

Characteristics of T lymphocyte isolates

The volume of cord blood that could be harvested from IUGR babies was significantly less than that from AGA babies (Table 2). However, this did not compromise the number of T lymphocytes isolated per unit volume of cord blood which was comparable between the two groups with good preservation of cell viability in both groups (Table 2). It is noteworthy that in several placentas from IUGR pregnancies, the volume of cord blood that could be harvested was below the threshold required for the successful execution of the isolation procedure, limiting the number of samples that could be analyzed.

TABLE 2.

Umbilical cord blood volume harvested and number and viability of T lymphocytes isolated from the umbilical cord blood of AGA and IUGR babies

| AGA§ | IUGR | |

|---|---|---|

| Blood volume harvested (ml) | 38.9 ±1.8 (n = 27) | 31.0 ± 3.4 (n = 9)* |

|

No of T lymphocytes isolated

(106/10 ml cord blood) |

7.6 ± 0.7 (n = 26) | 5.8 ± 1.2 (n = 9) |

| Cell viability (%) | 97.8 ± 0.7 (n = 24) | 99.2 ± 0.4 (n = 9) |

The number of AGA samples is different between variables measured because of incomplete data.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

p<0.05 v AGA (two-tailed Student’s t test).

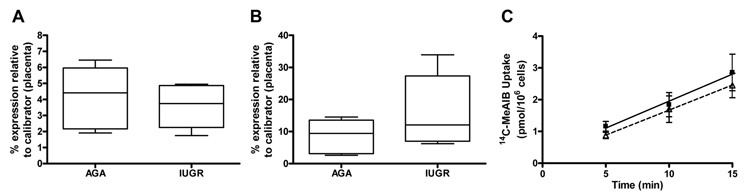

System β

Figure 1 confirms TAUT mRNA expression in fetal T lymphocytes from both AGA and IUGR groups. Relative TAUT mRNA expression was significantly lower in IUGR T lymphocytes compared to AGA lymphocytes (Figure 1B). The identity of the TAUT mRNA was confirmed by the generation of a single amplicon of appropriate size (117 bp) in all samples which co-migrated with placenta as positive control. The lack of difference in β-actin mRNA expression between lymphocytes in each group (Figure 1A) confirms comparable cDNA integrity in both groups. System β activity, measured as 3H taurine uptake over 5–15 min, was time-dependent and linear and not different (2-way ANOVA) between groups (Figure 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Expression of (A) β-actin and (B) TAUT mRNA in AGA (n=5) and IUGR (n=6) fetal T lymphocytes; and (C) 3H-taurine uptake by fetal T lymphocytes from AGA (■, n=6; r2=0.995, p<0.05, solid line) and IUGR (△, n=6; r2=0.998, p<0.05, dashed line) babies. Data in Figures 1A and 1B are presented as box and whiskers (box extends from the 25th to the 75th centile, whiskers represent range and horizontal line is median). * p<0.01 v IUGR, two-tailed Mann-Whitney test. In Figure 1C the linear regression plot is shown with data presented as mean ± SEM.

System A

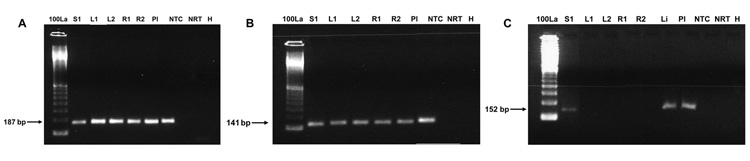

Gene expression studies of system A subtypes in fetal T lymphocytes demonstrated expression of SLC38A1 (SNAT 1) and SLC38A2 (SNAT2) mRNA whereas SLC38A4 (SNAT 4) mRNA was undetectable (no cycle threshold value recorded) despite clear visualization of SLC38A4 amplicon in the positive controls (Figure 2). This observation was consistent between the two groups of fetal T lymphocytes (Figure 2) and so mRNA expression of SLC38A1 and SLC38A2 only was compared (Figure 3). SLC38A1 and SLC38A2 amplification products detected in T lymphocytes from both groups were of the predicted size and co-migrated with positive controls (Figure 2). There was no difference in SLC38A1 and SLC38A2 mRNA expression between AGA and IUGR T lymphocytes (Figures 3A and 3B). System A activity, as represented by uptake of 200μM 14C-MeAIB over 5-15 min, was time-dependent and linear and was not different (2-way ANOVA) between AGA and IUGR T lymphocytes (Figure 3C).

FIGURE 2.

Gel electrophoresis of qPCR products for (A) SLC38A1 (SNAT1), (B) SLC38A2 (SNAT2) and (C) SLC38A4 (SNAT 4) in standard (S1=100ng), AGA lymphocyte (L1, L2), IUGR lymphocyte (R1, R2), placenta (Pl), liver (Li) and negative controls (lanes NTC, NRT and H). The products were of the expected size of 187, 141 and 152 bp respectively. NTC = no template control; NRT = no reverse transcriptase; H = H20. 100La = 100 bp ladder.

FIGURE 3.

Relative mRNA expression of (A) SNAT 1 and (B) SNAT 2 in AGA (n = 5) and IUGR (n = 6) fetal T lymphocytes; and (C) 14C-MeAIB uptake by fetal T lymphocytes from AGA (■, n = 6; r2 = 0.987, p = 0.07, solid line) and IUGR (△, n = 6; r2 = 0.999, p = 0.02, dashed line) babies. Data in Figures 3A and 3B are presented as box and whiskers (box extends from the 25th to the 75th centile, whiskers represent range and horizontal line is median). SNAT 1 and SNAT 2 mRNA expression was comparable between the groups. In Figure 3C the linear regression plot is shown with data presented as mean ± SEM.

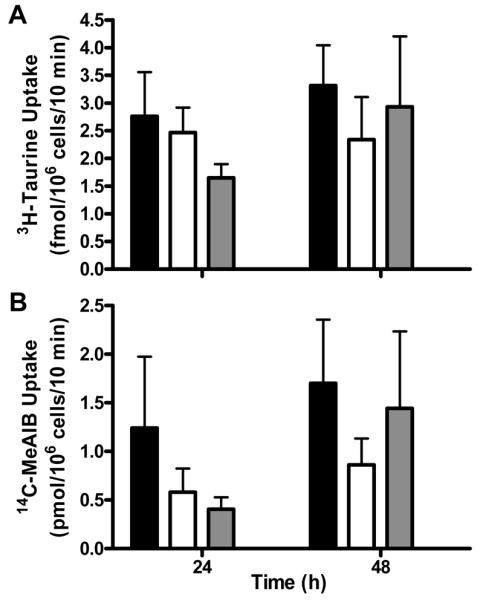

TNF-α treatment of fetal T lymphocytes

Fetal T lymphocyte cell viability was unaltered after 24h incubation with either 20ng/ml or 50ng/ml TNF-α. However, after 48h of culture with 50ng/ml TNF-α, T lymphocyte cell viability was significantly (p<0.05) reduced (89.5 ± 3.1%; mean ± SEM) compared to control cells without TNF-α treatment (97.7 ± 0.8%) as shown in Figure 4. After 24 and 48h culture, TNF-α did not affect activity of either system β or system A in fetal T lymphocytes (Figure 5). For all the treatment groups, system A activity was significantly raised after 48h of culture (p<0.05; 2-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test).

FIGURE 4.

Fetal T lymphocyte viability after 24 and 48h culture without (control; ■) or with 20 ng/ml (□) or 50ng/ml ( ) TNF-α. Cell viability was significantly reduced by 50ng/ml TNF-α after 48h (2-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post test). Data is presented as mean + SEM, n = 6; *p< 0.05 control v 50 ng/ml TNF-α.

) TNF-α. Cell viability was significantly reduced by 50ng/ml TNF-α after 48h (2-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post test). Data is presented as mean + SEM, n = 6; *p< 0.05 control v 50 ng/ml TNF-α.

FIGURE 5.

Uptake of (A) 3H-taurine by system β and (B) 14C-MeAIB by system A in fetal T lymphocytes after 24 and 48h culture without (control; ■) or with 20 ng/ml (□) or 50ng/ml ( ) TNF-α. TNF-α had no effect on either taurine or MeAIB uptake. Data is presented as mean + SEM, n = 5 for both.

) TNF-α. TNF-α had no effect on either taurine or MeAIB uptake. Data is presented as mean + SEM, n = 5 for both.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have examined whether the altered amino acid transport function observed in the placentas of IUGR pregnancies (5, 13) is also reflected in other fetal cells outside of the placenta. To address this issue we have focused on two amino acid transport systems, system β and system A, the activities of which are reduced in the placentas of IUGR pregnancies (8, 9, 11). We elected to use fetal T lymphocytes as a fetal cell model as these cells are readily accessible, and can be isolated to a high degree of purity, constituting a well-characterized fetal cell population in which transport function can be examined (17).

The IUGR babies in this study were delivered at term, there being no difference in gestational age compared to the AGA babies, suggesting that these were mild to moderate IUGR cases that did not necessitate preterm clinical intervention. However, evidence of growth restriction was supported by the significantly lower birthweight of this group. Although several severely growth restricted babies were recruited to the study, minimal cord blood could be obtained at birth or the T lymphocytes isolated were heavily contaminated with red blood cells precluding their use, thereby limiting the number of samples available in this study. We speculate that this contamination most likely arises from nucleated red cells, as the nucleated red cell count in cord blood is increased in pregnancies complicated by IUGR (21). Although a lower blood volume was harvested from the placenta of IUGR pregnancies, there was comparability in the number of cells isolated per unit volume, suggesting cell recovery was equally efficient in both groups. Despite the reduced expression of TAUT mRNA observed in IUGR T lymphocytes, system β activity in these cells was unaltered, suggesting discordance between TAUT mRNA expression and system β activity. This is interesting in the light of other studies reporting divergence between expression of TAUT and system β activity in placenta (22). The reduced abundance of TAUT mRNA in IUGR T lymphocytes was not mirrored by a change in SLC38A1, SLC38A2 or β-actin mRNA levels, suggesting this response was TAUT-specific and not reflective of a generalised downregulation in cellular transcription in the IUGR group. We were not able to measure the Na+-dependent component of 3H-taurine as an index of system β activity in this study (or for system A) due to the constraints in the number of cells recovered (~18 × 106 cells in IUGR group; Table 2) and the requirement for 3-5 × 106 cells per activity measurement (17).

In this study we have confirmed that system A is expressed and functionally active in fetal T lymphocytes, as evidenced by the uptake of radiolabelled MeAIB, considered a paradigm substrate for this transport system (18). This would be anticipated based on the ubiquitous expression of system A and its key role in the cellular provision of neutral amino acids (18). System A activity demonstrated here is likely to be by SNAT1- and SNAT2-mediated activity, based on the demonstration of mRNA expression for both these isoforms in this cell type. Whilst SLC38A2 (SNAT2) mRNA expression has a broad tissue distribution with ubiquitous expression, SLC38A1 (SNAT1) exhibits a more restricted expression (23, 24), leading to the proposal that SNAT2 is likely to represent the classic system A transporter. Several tissues, including placenta, co-express both SNAT1 and SNAT2 transcripts (20, 24, 25), as shown here in fetal T lymphocytes. The lack of SNAT4 mRNA in fetal T lymphocytes is interesting as other fetal cell types within the human placenta, notably syncytiotrophoblast and fetal capillary endothelium, express SNAT4 (20). This study therefore highlights the cell-specific nature of fetal SNAT4 expression and suggests that SNAT4-mediated amino acid transport subserves a cell-specific role in amino acid provision. Rodent placenta also expresses SNAT4 (25), implicating an important role for SNAT4 in placental function, perhaps related to fetal growth and development (20).

The observations made here, that system β or system A amino acid transporter activity in fetal T lymphocytes is not altered in IUGR, as compared with that in AGA infants, contrasts with previous placental studies that have shown a reduction in the activity of these transporters in the syncytiotrophoblast plasma membranes in IUGR pregnancy (5,13). The studies on placenta showing differences in amino acid transporter activity include term IUGR clinical groups similar to those studied here (7) as well as more severely affected groups (8). Other studies have further suggested that the reduction in system A activity plays a causative role in inducing IUGR (26-28), compatible with the observation that the magnitude of diminution in system A activity in MVM relates to the severity of IUGR (8). Our observation that neither system β nor system A activity is altered in fetal T lymphocytes implies that the aberrant functional phenotype of syncytiotrophoblast in IUGR pregnancy (5, 13) is not manifest in all fetal cells. A reduced amino acid transporter activity in fetal T lymphocytes might influence their proliferation and differentiation impacting on neonatal host-defence mechanisms (29).

A regulatory feature of both system β and system A is the ability to undergo adaptive regulation, being upregulated by extracellular substrate starvation. This is pertinent with regard to IUGR as the concentration of some essential amino acids in cord plasma is reduced (3, 4). Our observations, as evidenced by the lack of change in both transporter activities in fetal T lymphocytes from IUGR pregnancies compared to the AGA group, argues against these cells having evoked an adaptive regulation response in relation to these transport mechanisms. Consistent with this notion, there was no evidence in fetal T lymphocytes of upregulated TAUT and SLC38A2 gene transcription associated with adaptive regulation (14).

Our studies on the treatment of fetal T lymphocytes with TNF-α have shown that this cytokine had no effect on the activity of amino acid transport systems β and A despite a small reduction in cell viability after 48h with 50ng/ml TNF-α. Previous studies suggest that treatment with TNF-α may cause DNA damage and an increase in the percentage of apoptotic cells at concentrations greater than 10ng/ml (30). The ability of TNF-α to stimulate amino acid transport is restricted to certain cell types (31). We cannot exclude the possibility that the effects of TNF-α were acute and transitory. However, system A transporter activity appeared to increase after the lymphocytes were incubated for 48h, despite a reduction in viability following 50ng/ml TNF-α treatment. It is not clear what the stimulus for system A amino acid transport might be as the increase in 14C-MeAIB took place irrespective of TNF-α treatment. Adaptive upregulation of this amino acid transporter is a possibility (14), arising from the cellular consumption of amino acids.

To summarise, this is the first study to investigate amino acid transporter activity in a readily available, non-passaged cell type outside the placenta in IUGR. The reduction in TAUT mRNA in fetal T lymphocytes from IUGR babies is at variance with a lack of change in system β activity, although the relationship between mRNA expression, protein expression and amino acid transporter activity is complex with evidence for a lack of direct correspondence between these variables (20, 22). The presence of SLC38A1 and SLC38A2 transcripts in fetal T lymphocytes and the absence of SLC38A4 transcripts suggest SNAT4 is not involved in fetal T lymphocyte metabolism, and that system A activity in these cells is mediated by SNAT1 and SNAT2 subtypes. The activity of system β and system A in fetal T lymphocytes from AGA pregnancies was not affected by exposure to TNF-α over a 48h timeframe, although cellular responsiveness to TNF-α was inferred by the observation of a significant reduction in viability at the highest dose applied. We conclude that the impaired transporter phenotype described in the syncytiotrophoblast (5, 13) is not present in fetal T lymphocytes and further, that there is not a unified downregulation of amino acid transporter activity in all fetal cells from IUGR pregnancy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the midwives and medical staff at St. Mary’s Hospital, Manchester, for their help in obtaining placentas.

Financial Support: Supported by a Wellcome Trust project grant (071224/Z/03/Z)

ABBREVIATIONS

- AGA

appropriate for gestational age

- BM

basal plasma membrane

- MeAIB

α-(methylamino)isobutyric acid

- MVM

microvillous plasma membrane

- SNAT

sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter

- TAUT

taurine transporter

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chiswick ML. Intrauterine growth retardation. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;291:845–848. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6499.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pryor J. The identification and long term effects of fetal growth restriction. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:1116–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb10933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Economides DL, Nicoliades KH, Gahl WA, Bernardini I, Evans MI. Plasma amino acids in appropriate- and small-for-gestational-age fetuses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:1219–1227. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cetin I, Ronzoni S, Marconi AM, Perugino G, Corbetta C, Battaglia FC, Pardi G. Maternal concentrations and fetal-maternal concentration differences of plasma amino acids in normal and intrauterine growth-restricted pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1575–1583. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70609-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansson T, Powell TL. Role of the placenta in fetal programming: underlying mechanisms and potential interventional approaches. Clin Sci. 2007;113:1–13. doi: 10.1042/CS20060339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jansson T. Amino acid transporters in human placenta. Pediatr Res. 2001;49:141–147. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200102000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahendran D, Donnai P, Glazier JD, D’Souza SW, Boyd RD, Sibley CP. Amino acid (system A) transporter activity in microvillous membrane vesicles from placentas of appropriate and small for gestational age babies. Pediatr Res. 1993;34:661–665. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199311000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glazier JD, Cetin I, Perugino G, Ronzoni S, Grey AM, Mahendran D, Pardi G, Sibley CP. Association between the activity of the system A amino acid transporter in the microvillous plasma membrane of the human placenta and the severity of fetal compromise in intrauterine growth restriction. Pediatr Res. 1997;42:514–519. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199710000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansson T, Ylvén K, Wennergren M, Powell TL. Glucose transport and system A activity in syncytiotrophoblast microvillous and basal membranes in intrauterine growth restriction. Placenta. 2002;23:386–391. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jansson T, Scholtbach V, Powell TL. Placental transport of leucine and lysine are reduced in intrauterine growth restriction. Pediatr Res. 1998;44:532–537. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199810000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norberg S, Powell TL, Jansson T. Intrauterine growth restriction is associated with reduced activity of placental taurine transporters. Pediatr Res. 1998;44:233–238. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199808000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chien PF, Smith K, Watt PW, Scrimgeour CM, Taylor DJ, Rennie MJ. Protein turnover in the human fetus studied at term using stable isotope tracer amino acids. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:E31–E35. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.265.1.E31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sibley CP, Turner MA, Cetin I, Ayuk P, Boyd CA, D’Souza SW, Glazier JD, Greenwood SL, Jansson T, Powell T. Placental phenotypes of intrauterine growth. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:827–832. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000181381.82856.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christie GR, Hyde R, Hundal HS. Regulation of amino acid transporters by amino acid availability. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2001;4:425–431. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200109000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartha JL, Romero-Carmona R, Comino-Delgado R. Inflammatory cytokines in intrauterine growth retardation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:1099–1102. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0412.2003.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang YS, Ohtsuki S, Takanaga H, Toni M, Hosoya K, Terasaki T. Regulation of taurine transport at the blood-brain barrier by tumor necrosis factor-alpha, taurine and hypertonicity. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1188–1195. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iruloh CG, D’Souza SW, Speake PF, Crocker I, Fergusson W, Baker PN, Sibley CP, Glazier JD. Taurine transporter in fetal T lymphocytes and platelets: differential expression and functional activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C332–C341. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00634.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackenzie B, Erickson JD. Sodium-coupled neutral amino acid (System N/A) transporters of the SLC38 gene family. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:784–785. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilcox MA, Johnson IR, Maynard PV, Smith SJ, Chilvers CE. The individualised birthweight ratio: a more logical outcome measure of pregnancy than birthweight alone. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:342–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb12977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desforges M, Lacey HA, Glazier JD, Greenwood SL, Mynett KJ, Speake PF, Sibley CP. SNAT4 isoform of system A amino acid transporter is expressed in human placenta. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C305–C312. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00258.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vatansever U, Acunas B, Demir M, Karasalihoglu S, Ekuklu G, Ener S, Pala O. Nucleated red blood cell counts and erythropoietin levels in high-risk neonates. Pediatr Int. 2002;44:590–595. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2002.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roos S, Powell TL, Jansson T. Human placental taurine transporter in uncomplicated and IUGR pregnancies: cellular localisation, protein expression and regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R886–R893. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00232.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hatanaka T, Huang W, Wang H, Sugawara M, Prasad PD, Leibach FH, Ganapathy V. Primary structure, functional characteristics and tissue expression pattern of human ATA2, a subtype of amino acid transport system A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1467:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Huang W, Sugawara M, Devoe LD, Leibach FH, Prasad PD, Ganapathy V. Cloning and functional expression of ATA1, a subtype of amino acid transporter A, from human placenta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273:1175–1179. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novak D, Lehman M, Bernstein H, Beveridge M, Cramer S. SNAT expression in rat placenta. Placenta. 2006;27:510–516. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cramer S, Beveridge M, Kilberg M, Novak D. Physiological importance of system A-mediated amino acid transport to fetal rat development. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C153–C160. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2002.282.1.C153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jansson N, Pettersson J, Haafiz A, Ericsson A, Palmberg I, Tranberg M, Ganapathy V, Powell TL, Jansson T. Down regulation of placental transport of amino acids precedes the development of intrauterine growth restriction. J Physiol. 2006;576:935–946. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.116509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Constância M, Hemberger M, Hughes J, Dean W, Ferguson-Smith A, Fundele R, Stewart F, Kelsey G, Fowden A, Sibley C, Reik W. Placental-specific IGF-II is a major modulator of placental and fetal growth. Nature. 2002;417:945–948. doi: 10.1038/nature00819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xanthou M. Immunological deficiencies in small-for-dates neonates. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl. 1985;319:143–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1985.tb10124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rangamani P, Sirovich L. Survival and apoptotic pathways initiated by TNF-alpha: modeling and predictions. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;97:1216–1229. doi: 10.1002/bit.21307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mochizuki T, Satsu H, Shimizu M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha stimulates taurine uptake and transporter gene expression in human intestinal CaCo-2 cells. FEBS Lett. 2002;517:92–96. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02584-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]