Abstract

Previous studies have identified subclinical lung disease in family members of probands with familial pulmonary fibrosis, but the natural history of preclinical pulmonary fibrosis is uncertain. The purpose of this study was to determine whether individuals with preclinical lung disease will develop pulmonary fibrosis. After a 27-year interval, two subjects with manifestations of preclinical familial pulmonary fibrosis, including asymptomatic alveolar inflammation and alveolar macrophage activation, were reevaluated for lung disease. CT scans of the chest, pulmonary function tests, and BAL were performed, and genomic DNA was analyzed for mutations in candidate genes associated with familial pulmonary fibrosis. One subject developed symptomatic familial pulmonary fibrosis and was treated with oxygen; her sister remained asymptomatic but had findings of pulmonary fibrosis on high-resolution CT scan of the chest. High concentrations of lymphocytes were found in BAL fluid from both subjects. Genetic sequencing and analyses identified a novel heterozygous mutation in telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT, R1084P), resulting in telomerase dysfunction and short telomeres in both subjects. In familial pulmonary fibrosis, asymptomatic preclinical alveolar inflammation associated with mutation in TERT and telomerase insufficiency can progress to fibrotic lung disease over 2 to 3 decades.

Trial registry:

ClinicalTrials.gov; No.: NCT00071045; URL: www.clinicaltrials.gov

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), the most common form of interstitial lung disease, is a chronic progressive disorder leading to death from respiratory failure. Since most patients present with symptoms and advanced disease, the natural history of IPF remains incompletely understood. Studying preclinical stages of familial pulmonary fibrosis, whose clinical manifestations are indistinguishable from those of IPF, will enhance the understanding of the natural history of IPF.

Familial pulmonary fibrosis is found in approximately 2% of patients with IPF and exhibits an autosomal dominant inheritance with incomplete penetrance.1 Approximately 15% of familial pulmonary fibrosis cases have mutations in telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), which encodes telomerase reverse transcriptase, or in telomerase RNA complex (TERC), coding for the RNA component of telomerase.2,3 In addition, blood leukocytes of 25% of patients with IPF demonstrate a shortened telomere despite the absence of telomerase mutations.4 Thus, it is plausible that mutations in other genes yet to be discovered are associated with pulmonary fibrosis and telomerase dysfunction.

Fibrosis is a recognizable clinical manifestation of telomere diseases.5 Mutations in telomerase complex genes result in low telomerase activity, progressive telomere shortening, and cell senescence, which may be translated clinically into bone marrow failure (aplastic anemia), liver disease, increased susceptibility to cancer, and pulmonary fibrosis. The prototypical telomere disease is dyskeratosis congenita, an inherited bone marrow failure syndrome in which a triad of nail dystrophy, skin reticular hypopigmentation, and leukoplakia are typical and diagnostic; cirrhosis and pulmonary fibrosis can also occur.

Several reports1,6,7 have described early stages of subclinical lung disease in familial pulmonary fibrosis. First-degree relatives of probands with familial pulmonary fibrosis showed evidence of inflammatory changes in the alveolar milieu (eg, high lymphocyte count in the BAL, abnormal gallium scans) without any detectable changes in pulmonary function tests or chest radiographs. Rosas et al8 found changes consistent with interstitial lung disease on high-resolution CT scans of the chest in 22% of asymptomatic relatives of familial pulmonary fibrosis probands. These subjects were significantly younger than probands and older than relatives without lung disease. These results strongly suggest that a period of asymptomatic disease precedes the diagnosis of familial pulmonary fibrosis. However, to our knowledge, there is no information available regarding the duration of preclinical disease in familial pulmonary fibrosis, and there is no definitive evidence demonstrating that people with alveolar inflammation or preclinical familial pulmonary fibrosis will manifest signs or symptoms of overt disease over time.

We report here the first, to our knowledge, long-term longitudinal follow-up of two siblings with asymptomatic alveolar inflammation that progressed to familial pulmonary fibrosis. This study proves the long-held, yet previously unsubstantiated, concept that preclinical familial pulmonary fibrosis can be present for 2 to 3 decades prior to developing into pulmonary fibrosis. In addition to defining the natural history of preclinical pulmonary fibrosis, a novel mutation in TERT was identified in this kindred and was associated with shortened telomeres and impaired telomerase activity.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Two subjects, who were previously part of a familial pulmonary fibrosis research study,6 provided written consent to participate in protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Human Genome Research Institute (04-HG-0211) and/or the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (04-H-0012). The two subjects were initially evaluated in 1982, and they were subsequently studied in 2009. Bronchoscopy and BAL were performed as previously described.9 Cytospins from BAL fluid cells were stained with Diffquik (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics; Deerfield, Illinois), and differential cell counts were performed. Pulmonary function testing was performed according to published guidelines.8 Bone marrow biopsy of the left posterior iliac crest was performed; slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Genetic Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes. Coding exons and intron-exon junctions of TERT, TERC, surfactant protein A2 (SFTPA2), and surfactant protein C (SFTPC) were amplified using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) containing 50 ng of genomic DNA, 3 μM of sense and antisense oligonucleotides, and 5 μL of HotStart Master Mix (Qiagen; Valencia, California) in a final volume of 10 μL. PCR products were sequenced in both directions using the Big Dye terminator kit v1.1 (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, California) and an automated capillary sequencer (ABI PRISM 3130xl Genetic Analyzer; Applied Biosystems). The same primers (Table 1) were used for PCR and sequencing. Electropherogram-derived sequences were compared with reference sequences for TERT (ENSG00000164362), TERC (ENSG00000244910), SFTPA2 (ENSG00000185303), and SFTPC (ENSG00000168484) using Sequencher software 4.8 (Gene Codes Corp; Ann Arbor, Michigan). Two hundred white control subjects (Coriell Institute for Medical Research; Camden, New Jersey) were screened for an identified missense mutation in TERT (c.3251 G>C; R1084P) and for a variant in TERT (A1062T) through direct sequencing. The mutation and variant in TERT were confirmed by independent testing (GeneDx; Gaithersburg, Maryland).

Table 1.

—Primers Used for PCR and Sequencing

| Gene | Sense Primer | Antisense Primer |

| TERT | ||

| Exon 1 | AGCCCCTCCCCTTCCTTT | CTCCTTCAGGCAGGACACCT |

| Exon 2a | ACCAGCGACATGCGGAGA | GTCGCCTGAGGAGTAGAGGAA |

| Exon 2b | GGTGTACGCCGAGACCAAG | CGTTCGTTGTGCCTGGAG |

| Exon 2c | CCGAGGAGGAGGACACAGAC | AAACCGCGTGTCCATCAA |

| Exon 3 | GTGTCCCCGTGTCCGAAT | GGAAAGGCAAGGAGGCTAGT |

| Exon 4 | GTGCTGATGGTGGGACAGT | TTGTGGTCCTCAGAGCCTGT |

| Exon 5 | CCCGTGTGCAACACACAT | AATAGGAGCCCGGGCAGT |

| Exon 6 | GGCAGAGGTGATGTCTGAGTT | AGATACATGCACCACGACACA |

| Exon 7 | GGAGTCCCAGGTGTGTCTGTA | CAAGGCACACAGCTCATCAT |

| Exon 8 | CGCACTTCATCACAAACACTG | CCAGAAAAGGAGACTCTGGTG |

| Exon 9 | GCTGAATGGTAGACGTGTCGT | CACTGAATGCATCAAAAGCAA |

| Exon 10 | AGAATTGCACAAGCTGATGGT | GAGAGGACTTGGCAGAGACAA |

| Exon 11 | TGCTCCAAATCACCACTTCTC | CCTCACTCCCACAGAAAGATG |

| Exon 12 | ACGCCCAACTCAGTGTTCTC | TCACACTGCACACCCACAC |

| Exon 13 | TCTCCTGGTTCCTTCCTGTCT | AGACATTCCTTGCCCCTAAAA |

| Exon 14 | TGCGTGTTCATACAGATGGTG | TCCTAAGCCCAGATTCACTCA |

| Exon 15 | GGAAATTTCACCTGGAGAAGC | CCAGCGTTTAATCACATAGGG |

| Exon 16 | GTCCTAGGAGGGTTGGAGGAT | ATTCCTATGTGGGGAGTGGAA |

| TERC | ||

| Exon 1 | TCATGGCCGGAAATGGAACT | GGGTGACGGATGCGCACGAT |

| SFTPA2 | ||

| Exon 3 | GAAGGTAACTGGGCATATGAGG | CTATCACTCCGTGGGCACTATG |

| Exon 4 | GAAGGACGTTTGTGTTGGAAGCC | TAACTGACTTCAGGTCGCTGTGC |

| Exon 5 | GAATATGAATTTGAGGGAGAAAGC | CATGTGCACGCTTGTTTGTC |

| Exon 6 | CTGCAATTGGAAGAGGAAGAG | TAAGGGTGCCTCCAGCTCTA |

| SFTPC | ||

| Exon 1 | ACCCAGGTTTGCTCTTGCT | TGAATGGATCTGGATAAGGAAA |

| Exon 2 | TGTTAGAATCCAGGCCACCT | CGTGCCTCTTTCCTTCTAGC |

| Exon 3 | CTCTTGGGAAAGAGGGAAGC | GGGAGAGATGGATGTGGATG |

| Exon 4 | CTAGTATGACTCCCGTGCCC | TGAGGAACAGTGCTTTACAGG |

| Exon 5 | TCAGCTGAGTCCACTCACTACC | GTACCGGTCTGTGAGCTTCC |

PCR = polymerase chain reaction; SFTPA2 = surfactant protein A2; SFTPC = surfactant protein C; TERC = telomerase RNA complex; TERT = telomerase reverse transcriptase.

Telomere Length Measurement

Telomere length of peripheral blood leukocytes was assessed by quantitative PCR as previously described.10 Total leukocytes were separated by ammonium-based lysis of RBCs and DNA extracted using the DNeasy Blood kit (Qiagen) from 172 healthy subjects, a group composed of volunteers who provided written consent to enroll in the institutional review board-approved protocol National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 07-H-0113 and anonymized blood or umbilical cord blood donors. Samples of blood bank and umbilical cord blood donors used for DNA extraction in this study were waste from existing blood typing test samples, subsequently anonymized, and, thus, not considered human subjects research. PCR was performed in a 7500 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The telomere length (x) of each sample was based on the telomere to single-copy gene ratio (T/S ratio) and based on the calculation of the ΔCt (Ct[telomeres]/Ct[single gene]). Telomere length was expressed as relative T/S ratio, which was normalized to the average T/S ratio of reference sample (2−[ΔCtx – ΔCtr] = 2−ΔΔCt). To calculate the 50th percentile for healthy subjects, the population was divided into five age groups (< 1, 1-29, 30-59, 60-90, and > 90 years), and a third-order polynomial best of fit curve for the 50th percentile as a function of age was generated using GraphPad Prism, version 4.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software; San Diego, California).

Telomerase Activity

Analysis of telomerase activity was performed for the TERT mutation (c.3251 G>C; R1084P), as previously described.11 Wild-type vector was mutated using an in vitro mutagenesis kit (Mutagenex Inc; Hillsborough, New Jersey). Vectors were transfected into telomerase-deficient VA13 cells along with a TERC-containing vector. Cells were lysed, and telomerase activity was quantified using a fluorescence assay (TRAPeze XL Telomerase Detection Kit; Millipore; Billerica, Massachusetts).11

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SE for n number of samples as compared with wild-type TERT. Significance of difference between means was evaluated using one-way analysis of variance. Group-by-group comparison was performed using Tukey test. A P < .05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 4.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software).

Results

Progressive Natural History of Familial Pulmonary Fibrosis

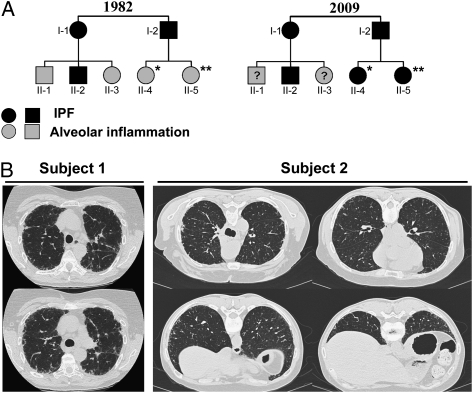

Two white sisters were initially evaluated at the National Institutes of Health in 1982 to 1983 as part of a familial pulmonary fibrosis study.6 Their father, paternal aunt, and cousin died of biopsy-proven IPF, but they were asymptomatic for lung disease (Fig 1A). (Subjects 1 and 2 were previously reported as B4 and B5 [family B in Reference 6], respectively.)6 Their clinical examination, chest radiographs, and pulmonary function tests were normal (Table 2), but they had alveolar inflammation and activated alveolar macrophages.6 Subjects 1 and 2 had high percentages of BAL lymphocytes and neutrophils. In addition, their alveolar macrophages spontaneously secreted a neutrophil chemoattractant, and alveolar macrophages from subject 2 secreted increased fibronectin and alveolar macrophage-derived growth factor.

Figure 1.

Features of siblings with familial pulmonary fibrosis and a mutation in telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT). A, Pedigree of the affected family in 1982 (adapted from Reference 6) and in 2009. *Indicates subject 1, **Indicates subject 2. B, Representative images from a CT scan of the chest from subject 1, which shows extensive interstitial infiltrates consistent with IPF, and high-resolution CT scan of the chest from subject 2, which shows mild subpleural reticulations and honeycombing consistent with early pulmonary fibrosis. IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Table 2.

—Longitudinal Follow-up of Preclinical Familial Pulmonary Fibrosis

| Subject 1 |

Subject 2 |

|||

| Measure | 1982 | 2009 | 1982 | 2009 |

| Age, y | 40 | 67 | 45 | 72 |

| Symptoms | None | Dyspnea, cough | None | None |

| Tobacco use | No | No | No | No |

| Oxygen requirement | No | Yes | No | No |

| Medicationsa | No | No | No | No |

| PFT | ||||

| TLC, % predicted | 112 | 84 | 110 | 113 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 127 | 98 | 119 | 125 |

| Dlco, % predicted | 101 | 54 | 80 | 80 |

| BAL fluid | ||||

| Lymphocytes, % | 26 | 24 | 20 | 46 |

| Neutrophils, % | 3 | 3.1 | 4 | 4 |

| Blood count (normal range) | ||||

| WBC (4.23-9.07 K/μL) | 3.4 | 5.31 | 4.5 | 4.7 |

| RBC (4.63-6.08 M/μL) | 3.79 | 3.66 | 3.3 | 3.73 |

| Hemoglobin (13.7-17.5 g/dL) | 13.2 | 12.4 | 11.3 | 12.6 |

| Hematocrit (40.1%-51%) | 38 | 37.4 | 32.1 | 38.8 |

| Platelets (161-347 K/μL) | 256 | 143 | 251 | 245 |

| Liver function tests (normal range) | ||||

| Albumin (3.7-4.7 mg/dL) | 4.3 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 3.3 |

| PT (11.6-15.2 s) | 12.0 | 14.5 | 11.9 | 13.5 |

| Bilirubin (0.1-1.0 mg/dL) | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Alk. Phos. (37-116 U/L) | 41 | 61 | 52 | 49 |

Alk. Phos. = alkaline phosphatase; Dlco = diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; PFT = pulmonary function test; PT = prothrombin time; TLC = total lung capacity.

Medications include any drugs that could cause or be used to treat lung diseases in general and IPF in particular.

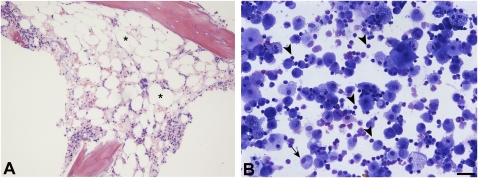

The subjects were reevaluated at the National Institutes of Health in 2009. Neither subject smoked cigarettes nor had any known exposures to drugs or substances that cause pulmonary fibrosis. Subject 1 reported development of significant impairment in her respiratory status and exercise tolerance starting in 2005, which resulted in treatment with continuous supplemental oxygen. From ages 40 to 67 years, total lung capacity declined from 112% to 84% predicted, diffusion capacity decreased from 101% to 54% predicted, and BAL lymphocytes were stable at 24%. A 6-min walk test showed a marked decline in oxygen saturation to 84%; high-resolution CT scan demonstrated findings consistent with pulmonary fibrosis (Fig 1B, left panel). Subject 1 had mild thrombocytopenia and macrocytosis, but her hemoglobin level and leukocyte counts were within the normal range, without evidence of frank bone marrow failure (Table 2). However, her bone marrow was hypoplastic (20%-30% cellularity), displayed mild megaloblastic changes, and had normal cytogenetics (Fig 2A). We found none of the stigmata characteristic of dyskeratosis congenita. Further, the autopsy report of the patients’ father reported pulmonary fibrosis and no other features of dyskeratosis congenita. From ages 45 to 72 years, subject 2 was asymptomatic for lung disease. She had normal and stable lung function, and her BAL lymphocytes increased from 20% to 46% (Fig 2B). However, a high-resolution CT scan of subject 2 showed mild reticulation and honeycombing, consistent with early pulmonary fibrosis (Fig 1B, center and right panels).

Figure 2.

Bone marrow hypocellularity and bronchoalveolar lymphocytosis. A, Bone marrow biopsy section from subject 1 showing increased fat cells (*) and a hypocellular marrow (20%-30% cellularity) without major dysplastic changes. (Hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification ×10). B, Representative field of a Cytospin preparation of BAL cells stained with Diffquik shows alveolar macrophages (arrows) and lymphocytes (arrowheads) from subject 2. Lymphocytes are markedly increased in the BAL specimen. (Diffquick stain, original magnification ×20, bar 50 μm).

Identification of a Mutation in TERT

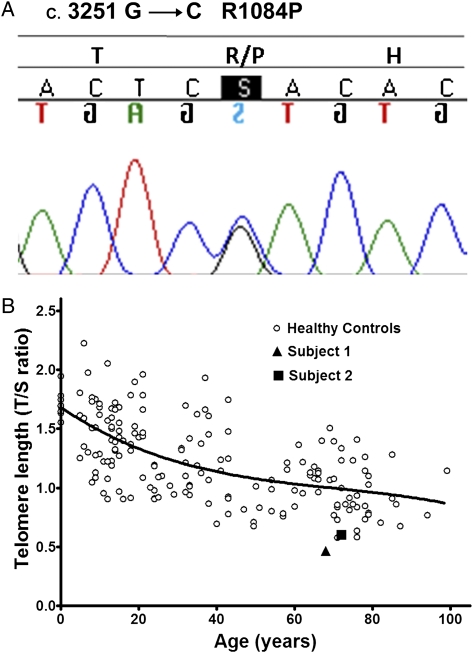

To determine whether subject 1 or 2 had mutations in genes associated with familial pulmonary fibrosis, coding exons of TERT, TERC, SFTPA2, or SFTPC were sequenced. We identified a novel missense mutation in exon 15 of TERT in the heterozygous state in both subjects. At position 3251 of the cDNA sequence, a cytosine replaced a guanine (c.3251 G>C) resulting in an amino acid change at position 1084 from arginine to proline (R1084P) (Fig 3A). An analysis of 400 alleles from white control subjects did not find a similar mutation. Subject 2 had another heterozygous nonsynonymous variant in TERT (Ala1062Thr [GCC>ACC]), which was found in 10 (5%) of the 200 control subjects and was not found in subject 1. No other mutations were found in TERT, TERC, SFTPA2, or SFTPC.

Figure 3.

Telomere mutation and length. A, Heterozygous change in cDNA position 3251 of TERT from guanine to cytosine, resulting in a substitution of arginine to proline at amino acid 1084 of telomerase in subjects 1 and 2. B, Blood leukocyte telomere length (relative T/S ratio) as a function of age of subject 1 and 2 and healthy control subjects. The two probands have an age-adjusted telomere length of less than the first percentile. The curve marks the 50th percentile of telomere length for healthy control subjects as a function of age. T/S ratio = telomere to single-copy gene ratio. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of the other abbreviation.

Telomere Length and Telomerase Activity

To evaluate whether the mutation (c.3251 G>C) found on TERT is associated with short telomeres in vivo, we measured telomere length in blood leukocytes. The mean age-adjusted telomere length in both subjects was less than the first percentile (Fig 3B).

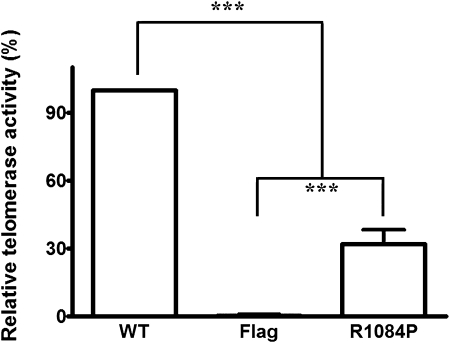

To determine the functional effects of the TERT mutation, we analyzed telomerase activity in cells expressing mutated TERT and compared it to that of cells expressing wild-type TERT. Consistent with our findings of short telomeres in subjects 1 and 2, telomerase activity was significantly reduced in cells expressing the mutated form of TERT compared with wild-type TERT. Specifically, substituting proline for arginine at amino acid 1084 was associated with 32% ± 2.6% of the telomerase activity of the wild-type protein (n = 6, P < .0001) (Fig 4). In addition, telomerase activity in cells with an R1084P mutation in TERT was significantly higher than that in cells that do not express telomerase (P < .001).

Figure 4.

Telomerase activity. Telomerase activity was quantified using mutated and WT vectors that were transfected into telomerase-deficient cells. Telomerase activity is significantly reduced in cells with an R1084P mutation in TERT compared with cells expressing WT telomerase and is significantly higher than that in cells that do not express telomerase (n = 6; ***P < .001). Flag = vector without TERT; WT = wild-type. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of the other abbreviation.

Discussion

This work defines the natural history of preclinical pulmonary fibrosis and demonstrates for the first time that alveolar inflammation in familial pulmonary fibrosis progresses to clinical disease over two to three decades. It also provides evidence that immune-cell dysregulation in the lung is a characteristic of early fibrotic lung disease. Furthermore, siblings at risk for familial pulmonary fibrosis, despite having an identical genetic mutation, can manifest variable long-term clinical outcomes. Although cigarette smoking and older age are the most important predictors of disease in familial pulmonary fibrosis,12 these factors cannot explain the dramatic differences in clinical outcome in this study, because both subjects were nonsmokers and the older sibling remains asymptomatic. This strongly suggests that other, yet unknown, genetic and/or environmental disease modifiers affect outcome in subjects with short telomeres and familial pulmonary fibrosis.

This study demonstrates that alveolar inflammation precedes the development of fibrotic lung disease. Our findings are consistent with other reports of dysregulated immunity in the lungs of people with preclinical familial pulmonary fibrosis and Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome, an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by early development of pulmonary fibrosis.8,13 It is possible that inflammation may be a primary cause of lung epithelial injury, or perhaps immune cell influx in preclinical pulmonary fibrosis may be a secondary response to injury.

Mutations in TERT and TERC have been identified in familial and sporadic pulmonary fibrosis. The two subjects did not undergo a surgical lung biopsy, but a recent study demonstrated that 86% of subjects with TERT mutations who underwent a lung biopsy have histopathologic features of usual interstitial pneumonia.14,15 Notably, consistent with this report, the CT scans in the subjects with TERT mutations showed that they had pulmonary fibrosis. The two siblings in this study had a novel TERT mutation resulting in a replacement of arginine with proline at position 1084 in the carboxy-terminal domain. This region of telomerase reverse transcriptase controls its steady state levels,16 and the C-terminal domain is implicated in telomerase processivity and enzyme localization.17 Notably, we found that this mutation resulted in short telomeres in vivo and significantly reduced telomerase activity in vitro. In addition, one sibling had a heterozygous nonsynonymous variant in TERT resulting in a replacement of alanine with threonine at position 1062. Reports on the effects of this variant on telomerase activity vary. Adler et al14 reported no effects on telomerase activity in vitro and in vivo, whereas Calado et al11 reported telomerase activity to be reduced in vitro to 60% via haploinsufficiency. Therefore, it is unlikely that this variant contributed to the better outcome in the older sibling. In this study, this variant had an allelic frequency of 2.5% in a white control population. The reported allelic frequency of this variant in the general ethnically diverse population is approximately 0.6%.11

This study has a few limitations. The sample size is small; however, these two subjects are sufficient to prove that preclinical familial pulmonary fibrosis evolves into overt disease after many years. In addition, the duration of preclinical lung disease may be underestimated by this study, because these subjects were not evaluated prior to the development of asymptomatic alveolar inflammation. Longitudinal follow-up of a cohort of young subjects with TERT or TERC mutations and no alveolar immune cell dysfunction may be informative to delineate the duration of preclinical lung disease in familial pulmonary fibrosis and to define the complete natural history of familial pulmonary fibrosis.

This report has important clinical implications. First, alveolar inflammation is a significant finding in the early development of pulmonary fibrosis, and, thus, may serve as a potential therapeutic target in people with subclinical disease. Second, the long duration of preclinical disease provides a large window of opportunity to intervene in subjects with familial pulmonary fibrosis. This suggests that clinical trials could be designed to intervene at much earlier stages of disease, which can be identified before extensive fibrosis and clinical symptoms have developed. Finally, although TERT mutations and short telomeres are associated with pulmonary fibrosis, they do not accurately predict the clinical phenotype, including severity of disease, which is relevant in discussing results of genetic testing and in counseling at-risk individuals.

Acknowledgments

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Other contributions: We thank Irina Maric, MD, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Clinical Center, for reviewing the bone marrow biopsy and the patients who participated in this study for their contributions.

Abbreviations

- IPF

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SFTPA2

surfactant protein A2

- SFTPC

surfactant protein C

- TERC

telomerase RNA complex

- TERT

telomerase reverse transcriptase

- T/S ratio

telomere to single-copy gene ratio

Footnotes

Funding/Support: This research was sponsored in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (http://www.chestpubs.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml).

References

- 1.Marshall RP, Puddicombe A, Cookson WO, Laurent GJ. Adult familial cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis in the United Kingdom. Thorax. 2000;55(2):143–146. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armanios MY, Chen JJ, Cogan JD, et al. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(13):1317–1326. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsakiri KD, Cronkhite JT, Kuan PJ, et al. Adult-onset pulmonary fibrosis caused by mutations in telomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(18):7552–7557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701009104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cronkhite JT, Xing C, Raghu G, et al. Telomere shortening in familial and sporadic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(7):729–737. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-550OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(24):2353–2365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0903373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bitterman PB, Rennard SI, Keogh BA, Wewers MD, Adelberg S, Crystal RG. Familial idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Evidence of lung inflammation in unaffected family members. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(21):1343–1347. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198605223142103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodgson U, Laitinen T, Tukiainen P. Nationwide prevalence of sporadic and familial idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence of founder effect among multiplex families in Finland. Thorax. 2002;57(4):338–342. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.4.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosas IO, Ren P, Avila NA, et al. Early interstitial lung disease in familial pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(7):698–705. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-254OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ren P, Rosas IO, Macdonald SD, Wu HP, Billings EM, Gochuico BR. Impairment of alveolar macrophage transcription in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(11):1151–1157. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-958OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(10):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calado RT, Regal JA, Hills M, et al. Constitutional hypomorphic telomerase mutations in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(4):1187–1192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807057106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steele MP, Speer MC, Loyd JE, et al. Clinical and pathologic features of familial interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(9):1146–1152. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200408-1104OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rouhani FN, Brantly ML, Markello TC, et al. Alveolar macrophage dysregulation in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome type 1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(11):1114–1121. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0023OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alder JK, Chen JJ, Lancaster L, et al. Short telomeres are a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(35):13051–13056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804280105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz de Leon A, Cronkhite JT, Katzenstein AL, et al. Telomere lengths, pulmonary fibrosis and telomerase (TERT) mutations. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(5):e10680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Middleman EJ, Choi J, Venteicher AS, Cheung P, Artandi SE. Regulation of cellular immortalization and steady-state levels of the telomerase reverse transcriptase through its carboxy-terminal domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(6):2146–2159. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2146-2159.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Autexier C, Lue NF. The structure and function of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:493–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]