Abstract

Purpose

Dendritic cells may be the most effective way of delivering oncolytic viruses to patients. Reovirus, a naturally occurring oncolytic virus, is currently undergoing early clinical trials; however, intravenous delivery of the virus is hampered by pre-existing anti-viral immunity. Systemic delivery via cell carriage is a novel approach currently under investigation and initial studies have indicated its feasibility using a variety of cell types and viruses. This study addressed the efficacy of human dendritic cells (DC) to transport virus in the presence of human neutralizing serum.

Experimental Design

Following reovirus-loading, DC or T cells were co-cultured with melanoma cells ± neutralizing serum; the melanoma cells were then analyzed for cell death. Following reovirus loading, cells were examined by electron microscopy to identify mechanisms of delivery. The phagocytic function of reovirus-loaded DC was investigated using labelled tumour cells and the ability of reovirus-loaded DC to prime T cells was also investigated.

Results

In the presence of human neutralizing serum DC, but not T cells, were able to deliver reovirus for melanoma cell killing in vitro. Electron microscopy suggested that DC protected the virus by internalization, whereas with T cells it remained bound to the surface and hence accessible to neutralizing antibodies. Furthermore, DC loaded with reovirus were fully functional with regard to phagocytosis and priming of specific anti-tumour immune responses.

Conclusions

The delivery of reovirus via DC could be a promising new approach offering the possibility of combining systemic viral therapy for metastatic disease with induction of an anti-tumour immune response.

Keywords: reovirus, cancer, dendritic cells, cell carriage, immune response

Introduction

Spontaneous cancer regression following natural viral infection has been reported since the early 1900s. Recently there has been renewed interest in viral therapy for cancer and several viruses have been evaluated in clinical trials(1-3). Oncolytic viruses preferentially replicate in and kill tumour cells, tumour selectivity being dependent on differences in the cellular processes of normal versus tumour cells; furthermore, genetic modification of the viruses can improve their tumour selectivity, safety and efficacy(4). However, delivery of oncolytic viruses is severely restricted by the immune response to systemically administered virus particles.

Reovirus is a non-enveloped, double-stranded RNA virus not normally associated with overt disease in humans. It preferentially replicates in and kills transformed cells with activated ras signalling(5), an aberration frequently seen in human cancers(6-10). Reoviruses are currently undergoing evaluation as oncolytic agents in clinical trial(2). For oncolytic viral therapy to achieve its full potential in the treatment of disseminated disease, effective systemic delivery will most likely be required. However, as reovirus is ubiquitous in the environment(11), most adults possess anti-reoviral antibodies due to prior exposure(12, 13). Moreover, antibody titre increases dramatically following intravenous (i.v.) therapy(14), so that neutralization by specific antibodies(15, 16) hampers efficient i.v. delivery. The use of cell carriers to transport viral particles within the circulation and deliver them to tumours is currently under investigation as a novel approach to systemic delivery. Preclinical studies have shown that various carrier cells including, T cells(17), monocytes, endothelial cells(18) and irradiated tumour cells(19) can carry virus within the circulation.

In addition to direct tumour cell lysis, it is becoming increasingly clear that oncolytic viruses may have a role in modifying the immune response to tumours. Oncolytic viruses have the potential to break immune tolerance to the tumour by releasing tumour antigens for uptake by DC and providing the danger signal required for immune activation(20), thus providing a rationale for the therapeutic combination of DC and oncolytic viruses.

Having recently demonstrated that DC could deliver reovirus for the clearance of metastases from lymph nodes in mice with pre-existing immunity to the virus(21), this study sought to evaluate the potential of human DC to act as cell carriers for reovirus. We show that both human DC and T cells were effective carriers of reovirus in vitro in the absence of human serum, but that only DC were able to deliver the virus for tumour cell killing when neutralizing serum was present. Electron microscopy suggested that this was owing to the different localization of the virus on the two cell types, DC being able to protect the virus by internalization, while on T cells it remained surface-bound and accessible to neutralization by serum components. Furthermore, DC loaded with reovirus were fully functional with regard to phagocytosis of tumour cells and priming of adaptive anti-tumour immune responses. Thus, in addition to viral protection and delivery, human DC may be particularly effective for enhancing therapy via induction of anti-tumour immunity in patients even in the presence of neutralizing antibodies.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Virus

Reovirus Type 3 Dearing was provided by Oncolytics Biotech Inc. (Calgary, Canada). Viral titres were measured by standard plaque assay on L929 cells. The human melanoma cell lines Mel-888 and MeWo were obtained from the Cancer Research UK cell bank and cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) plus 10% (v/v) FCS (Biosera) and 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were passaged for fewer than 6 months from thawing; they were routinely tested for mycoplasma and found to be free of infection. Human PBMC were obtained from buffy coats of healthy donors by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation. iDC were derived from monocytes isolated using anti-CD14 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech) and cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) plus 10% (v/v) FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 800 U/ml GMCSF (Peprotech) and 500 U/ml IL-4 (R&D Systems) for 4 days. mDC were generated by culture of 3½ day iDC with 10 μg/ml OK432(22) (Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Japan). T cells were isolated by negative selection of the CD14− PBMC fraction using Pan T selection beads (Miltenyi Biotech) and cultured in RPMI 1640 + 10% FCS + 2 mM L-glutamine.

Flow Cytometry

A FACSCalibur (Becton-Dickinson) was used for acquisition and Cell Quest Software (BD Biosciences) for analysis. Antibodies: anti-JAM1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-human HLA-DR-PE, CD11c-APC, CD80-PE, CD86-PE, CCR7-PE, IFN-γ-FITC, CD107a-FITC, CD107b-FITC, CD3-FITC, CD8-PerCP, anti-mouse Ig-FITC (BD Pharmingen); reovirus loading was detected using anti-reovirus σ3 capsid protein (DSHB, University of Iowa, USA) followed by anti-mouse IgG-FITC.

Reovirus Loading of Carrier Cells

5 × 106 aliquots of iDC, mDC or T cells were loaded with reovirus at: 0; 1; or 10 pfu/cell; in a total volume of 1 ml PBS, at 4°C for 3 h, then washed twice in 13 ml PBS.

Reovirus retention

Estimation of surface reovirus retention was performed by FACS and plaque assay after loading cells ± 10 pfu/cell reovirus at 4°C. For FACS analysis, cells were labelled with anti-reovirus σ3 followed by FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (BD Pharmingen). For plaque assay, cells were re-suspended in 100 μl PBS and freeze-thawed (3 cycles, 10 min freeze in methanol/dry ice followed by 10 min thaw at 37°C); this preparation was used in a standard plaque assay on L929 cells. Removal of sialic acid was by incubation with 5.5 mU/ml sialidase (Roche) at 37°C for 1 h in serum-free medium.

In Vitro Delivery of Reovirus via Carrier Cells

Target cells (Mel-888, MeWo) were seeded at 3 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates and allowed to adhere for 3 h. Direct reovirus was added at 0, 1 or 10 pfu/target cell. For delivery via cell carriage, iDC, mDC or T cells were loaded with reovirus at 0, 1 or 10 pfu/cell and added to melanoma targets at a 1:1 ratio. Human blocking serum was added to the wells at 0, 2 or 30 % (v/v). After a further 48 and 72 h, wells were harvested, cells were labelled with FITC-conjugated anti-CD11c or anti-CD3 to allow gating out of carrier cells, stained with propidium iodide (Sigma) and analyzed for target cell death by flow cytometry. For JAM-1 blocking, 10 μg/ml anti-JAM-1 was added to MeWo cell cultures and incubated for 30 min; reovirus or reovirus-loaded carrier cells were then added. After 48 h the cells were harvested and cell death was analyzed as described above.

Electron Microscopy

DC and T cells were loaded ± reovirus at approx 170 pfu/cell, washed, re-suspended in medium and placed at 37°C for 6 h to allow internalization of the virus to take place, after which time the cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldeyhde in 0.1 M PHEM buffer (60 mM PIPES, 25 mM HEPES, 10 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2) for 2 h at RT. Fixed cells were stored in 0.1 M PHEM, 0.5% PFA at 4°C until they were pelleted and embedded in 12% gelatin. The pellet was cut into approx 1 mm2 cubes, which were cryo-protected in 2.3 M sucrose and subsequently snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Ultrathin crysections were incubated with anti-reovirus σ3 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank)(1:800), a bridging rabbit anti-mouse IgG antibody (Dako Cytomation , Denmark) (1:200) and protein A-gold particles 10 nm. The specimens were viewed with a FEI Tecnai 12 Biotwin transmission electron microscope operating at 120 kV. Digital images were collected with a cooled charge-couple device (CCD) camera (4K Eagle, FEI company) at binning 2 to a final size of 2048 × 2048 pixels.

Phagocytosis assay

Mel-888 cells were labelled with 1 μM Celltracker Green (Invitrogen) at 37°C for 30 min, then washed twice in medium and seeded in 6-well plates at 3 × 106 cells/well. 3 × 106 aliquots of PFA-fixed or living iDC or mDC were loaded ± reovirus at 10 pfu/cell and cultured with the labelled Mel-888 cells at a 1:1 ratio for 4 h. Cells were then harvested, DC were labelled with anti-CD11c and double positive cells were identified by flow cytometry.

Generation of Tumour-specific CTL

Reovirus at 0 or 10 pfu/cell, or iDC, mDC or T cells loaded with reovirus at 0 or 10 pfu/cell were cultured with Mel-888 cells (1:1 ratio) for 24 h. Non-adherent cells were harvested and co-cultured with autologous isolated T cells or whole PBMC at a ratio of 1:10 – 1:30 in CTL medium (RPMI 1640 plus 7.5% (v/v) human AB serum (Sigma), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% (v/v) sodium pyruvate (Sigma), 1% (v/v) non-essential amino acids (Sigma), 1% (v/v) Hepes (Sigma), 20 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma) and 5 ng/ml IL-7 (R&D Systems)). Cultures were re-stimulated using the same protocol after 1 week. Cells were harvested at day 14.

CD107 Lymphocyte Degranulation Assay

As a measure of cytotoxicity a lymphocyte degranulation assay was used as previously described(23). CTL and tumour targets were cultured at a 1:1 ratio in CTL medium; anti-CD107a and anti-CD107b antibodies + 10 μg/ml brefeldin A (Invitrogen) were added after 1 h. After a further 4 h culture, CTL were labelled with anti-CD8 and analyzed by flow cytometry.

ELISA

IFN-γ ELISA assays were carried out using matched antibody pairs (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistics

A paired Student's t test was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

Human DC and T cells can be loaded with reovirus

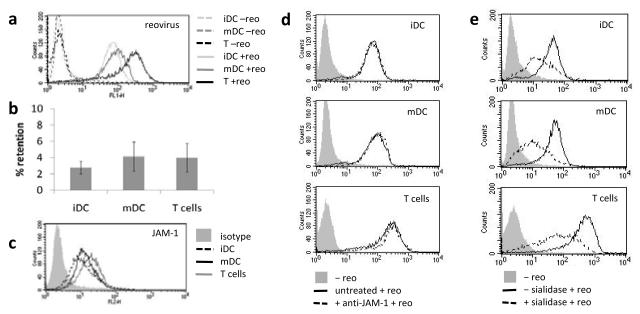

Delivery of reovirus type 3 Dearing to tumour cells, via cell carriage on DC and T cells, has previously been demonstrated in mouse models. Since carriage of reovirus by human immune cells has not yet been demonstrated, human immature DC (iDC), mature DC (mDC) and T cells were investigated for their potential to deliver reovirus to tumours. Reovirus was detected on loaded iDC, mDC and T cells by both FACS for surface-bound virus (Fig. 1a) and plaque assay. FACS analysis indicated more surface-detectable reovirus on T cells than DC. Plaque assay indicated that low levels of virus (around 4% of the loading dose) could be retrieved from the carrier cells, with no significant difference between iDC, mDC and T cells (Fig. 1b). Replication of the virus within cells, which would serve to increase the dose of virus delivered to the tumour, was not detected within human DC or T cells (data not shown). Junction adhesion molecule 1 (JAM-1) has been identified as a cellular receptor for reovirus type 3(24) and was found to be expressed at broadly similar levels by iDC, mDC and T cells (Fig. 1c). However, JAM-1 was not required for loading, as blocking JAM-1 did not inhibit reovirus-loading of DC or T cells (Fig. 1d). Reovirus can also bind to sialic acid residues(25) which therefore represent an alternative cellular target for reovirus loading. Treatment of DC and T cells with sialidase to remove sialic acid prior to virus loading, significantly reduced reovirus retention by all three cells types (Fig. 1e), suggesting sialic acid is important for effective loading of these carrier cells.

Figure 1.

(a) FACS analysis for reovirus retention on iDC, mDC and T cells, plots are representative of 4 independent experiments. (b) freeze/thaw preparations of reovirus loaded cells were used in a standard plaque assay and reovirus retention as a % of the loading dose was calculated. Graph shows mean ± SE of data from 6 independent experiments. (c) FACS analysis for Jam-1 expression on iDC, mDC and T cells; representative of 4 independent experiments. (d,e) FACS plots showing reovirus retention following blocking of the carrier cells with anti-Jam-1 antibody prior to reovirus loading (d), and removal of sialic acid from the carrier cells prior to loading (e); representative of 4 independent experiments.

Human DC and T cells deliver reovirus for tumour cell killing

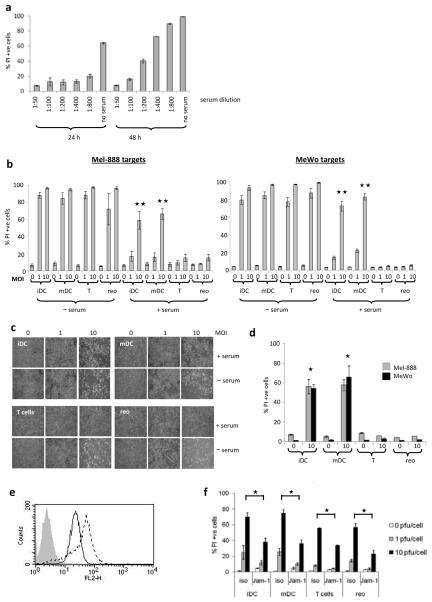

Human neutralizing serum protected melanoma cells from reovirus-induced cell death (Fig. 2a), suggesting that reovirus may be neutralized following systemic delivery in patients. Therefore, the potential delivery of reovirus via human cell carriage was examined. In the absence of human serum, both virus-loaded DC and T cells were able to deliver reovirus for melanoma cell killing as demonstrated by the percentage of PI positive cells (Fig. 2b) and by microscopy (Fig. 2c). In the mouse, delivery of reovirus via cell carriage was more efficient than direct viral delivery in vitro(21). Similar results were seen here in the human system, where the percentage of virus retained by the DC and T cells after loading was low (approx. 4%, Fig. 1c), but the resulting tumour target cell death was as high as that induced by direct virus at the full loading dose (Fig. 2b). However, the presence of 2% human serum abrogated reovirus-induced tumour cell lysis when the virus was delivered either directly or via T cells. By contrast, both iDC and mDC were able to deliver reovirus for melanoma killing in the presence of serum, although cell death was partially inhibited (Fig. 2b). Efficient reovirus delivery via DC (but not T cells) was also demonstrated in the presence of the more physiological level of 30% human serum (Fig. 2d). Interestingly, target melanoma cells express JAM-1 (Fig. 2e) and blocking this JAM-1, did significantly reduce productive viral hand-off (Fig. 2f), indicating that JAM-1 expression by tumour cells is important for reovirus-dependent tumour cell killing.

Figure 2.

(a) Mel-888 cells were cultured with reovirus at 10 pfu/cell ± human serum at the dilutions shown. After 24 and 48 h the cells were harvested and PI stained to determine cell death. (b) iDC, mDC and T cells were loaded with reovirus at the MOI indicated and cultured ± human blocking serum at 1:50 dilution, with target Mel-888 or MeWo cells. At 72 h the cells were harvested and stained with PI for FACS analysis. Graphs show mean ± SE of data from 3 independent experiments;

denotes significance p < 0.01 between iDC or mDC vs T cells or neat reovirus, all at MOI 10. (c) MeWo cells were cultured for 48 h, with reovirus-loaded iDC, mDC or T cells, or neat virus at the MOI indicated, ± blocking serum. Carrier cells were removed, fresh PBS was added to the wells and phase-contrast images were taken. Images shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (d) Carrier cells loaded with reovirus, were cultured with Mel-888 or MeWo cells in the presence of 30% blocking serum for 72 h. Graph shows mean ± SE of data from 2 independent experiments;

denotes significance p < 0.01 between iDC or mDC vs T cells or neat reovirus, all at MOI 10. (c) MeWo cells were cultured for 48 h, with reovirus-loaded iDC, mDC or T cells, or neat virus at the MOI indicated, ± blocking serum. Carrier cells were removed, fresh PBS was added to the wells and phase-contrast images were taken. Images shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (d) Carrier cells loaded with reovirus, were cultured with Mel-888 or MeWo cells in the presence of 30% blocking serum for 72 h. Graph shows mean ± SE of data from 2 independent experiments;  denotes significance p < 0.05 between iDC or mDC vs T cells or neat reovirus. (e) FACS analysis showing Jam-1 expression by Mel-888 cells (solid line) and MeWo cells (broken line). (f) MeWo cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml anti-JAM-1 prior to the addition of reovirus or carrier cells loaded at the MOI shown. After 48 h culture the cells were harvested and stained with PI. Graph shows mean ± SE for 2 independent experiments;

denotes significance p < 0.05 between iDC or mDC vs T cells or neat reovirus. (e) FACS analysis showing Jam-1 expression by Mel-888 cells (solid line) and MeWo cells (broken line). (f) MeWo cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml anti-JAM-1 prior to the addition of reovirus or carrier cells loaded at the MOI shown. After 48 h culture the cells were harvested and stained with PI. Graph shows mean ± SE for 2 independent experiments;  denotes significance p < 0.05.

denotes significance p < 0.05.

DC internalize reovirus thus protecting it from neutralization

The efficacy of DC compared to T cells as carriers of reovirus in the presence of neutralizing serum, indicated that DC were somehow able to protect the virus from elimination, suggesting that the two cell types might employ different mechanisms for delivery. Owing to their phagocytic nature, particularly for virus-sized particles(26), it seemed possible that internalization of the virus by DC might be a mechanism whereby DC could ‘hide’ the virus during delivery to tumour cells. In addition, several viruses are internalized by DC following binding to DC-SIGN(27-29), which facilitates their dissemination(30, 31). T cells on the other hand might transport the virus on the surface leaving it accessible to neutralization. Therefore the location of reovirus on loaded DC and T cells was examined. Following reovirus loading at 4°C the DC and T cells were incubated at 37°C to allow any active internalization of the virus to take place, after which time they were fixed and examined by immunogold electron microscopy. Reovirus particles were predominantly seen in association with the T cell surface (Fig. 3b), but by contrast viral protein could be detected both at the surface and internally in iDC and mDC (Fig. 3a,c,d).

Figure 3.

iDC (a), mDC (c,d) and T cells (b) were loaded ± reovirus. The cells were then washed, re-suspended in medium and placed at 37°C for 6 h to allow internalization of the virus to take place, after which time the cells were fixed, immunogold labelled and analyzed by Electron Microscopy. Scale bars all 500 nm. N, nucleus; M, mitochondria; G, Golgi.

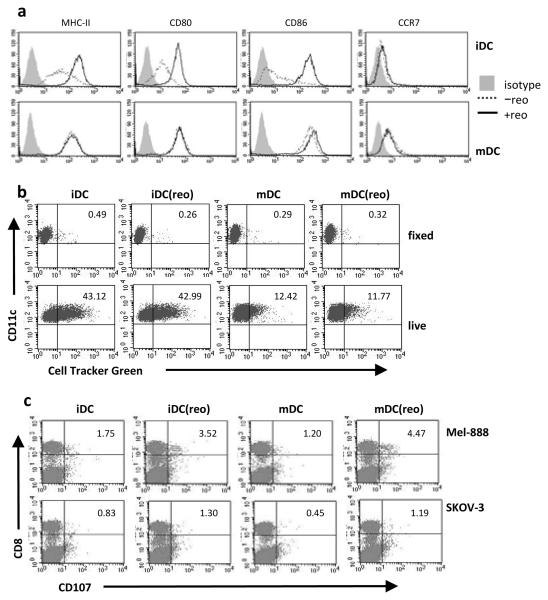

Reovirus does not inhibit DC maturation or function

Although it has previously been shown that reovirus can directly activate DC(20), tumour cells can impair DC maturation and function(32). Fig. 4a shows that reovirus loaded onto iDC was able to induce their maturation even in the presence of tumour cells, inducing upregulation of MHC-II, CD80 and CD86. Moreover, the presence of tumour cells did not alter the activated phenotype of previously matured DC (Fig. 4a). Hence, carrier DC entering the tumour site, or endogenous DC recruited to the tumour following therapy, should be activated for potential anti-tumour immune priming. In addition, reovirus loading did not impair the phagocytic function of DC, since both iDC and mDC loaded with reovirus phagocytosed melanoma cells at the same level as non-loaded DC (Fig. 4b). Thus, reovirus-loaded DC remain competent for antigen uptake, an essential component of anti-tumour immune cross-priming. The absence of double positive cells in the PFA-fixed controls (Fig. 4b) indicated that tumour cell uptake was an active process and not merely passive adhesion of the melanoma cells to DC. The ability of reovirus-loaded DC to prime an anti-tumour immune response in the context of viral hand off and target killing was investigated. Isolated autologous T cells, rather than complete PBMC, were used as responders for cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) generation, to exclude the possibility of any non-carrier, endogenous DC within the PBMC fraction contributing to priming. Reovirus-loaded DC were cultured with Mel-888 cells for 24 h; non-adherent cells (including carrier cells and dying melanoma cells) were then harvested and cultured with responder T cells. Both reovirus-loaded iDC and mDC were effective at priming specific anti-tumour CTL (Fig. 4c). Thus reovirus, as well as being directly cytotoxic to tumour cells, can act as an adjuvant to induce functional DC maturation leading to induction of specific anti-tumour immunity. Hence reovirus carriage by human DC has the potential to support immune-mediated as well as direct cytotoxic therapy.

Figure 4.

(a) iDC (top row) or mDC (bottom row) were loaded ± 10 pfu/cell reovirus, and cultured with Mel-888 cells in the presence of blocking serum; after 48 h the cells were harvested, labelled with CD11c and analyzed for the maturation markers indicated. Plots shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (b) PFA-fixed or live DC were loaded as in (a) and cultured with Cell Tracker Green-labelled Mel-888 cells, then harvested and labelled with CD11c. Double positive cells were identified by FACS. Plots shown are representative of 4 independent experiments. (c) reovirus-loaded cells (iDC(reo), mDC(reo)) or non-loaded cells (iDC, mDC), were cultured for 24 h with Mel-888 cells and used to prime isolated autologous T cells. Cells were harvested and a CD107 degranulation assay against Mel-888 or SKOV-3 (irrelevant) targets was performed. Plots shown are representative of 3 independent experiments; numbers indicate % of CD8 cells degranulating.

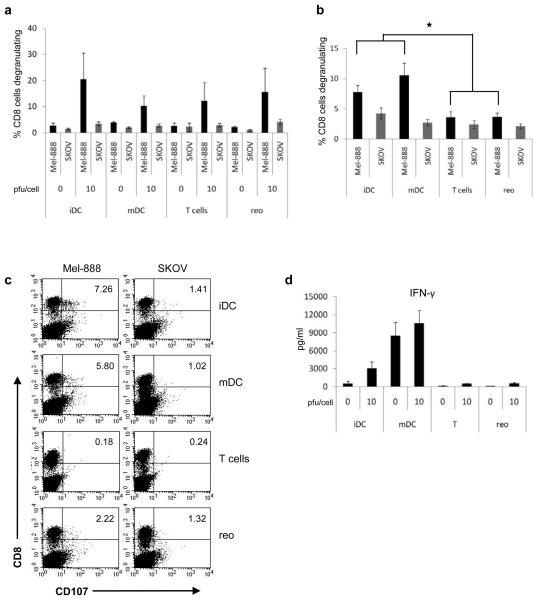

Reovirus-loaded DC prime anti-tumour immunity in the presence of human serum

The potential of reovirus-loaded T cells or direct reovirus to support specific anti-tumour immune priming was investigated, initially in the absence of serum, using whole PBMC rather than isolated T cells as responders for CTL generation, thus providing antigen presenting cells for antigen uptake and priming. Under these serum-free conditions, both direct reovirus and reovirus-loaded T cells induced anti-tumour immune priming to a level comparable to that of reovirus-loaded DC (Fig. 5a). However, consistent with the ability of DC but not T cells to protect reovirus from serum neutralization for direct cytotoxicity (Fig. 2b), only DC loaded with reovirus were effective in priming specific anti-tumour immunity in the presence of neutralizing serum (Fig. 5b,c). This suggests that in this in vitro system, reovirus hand-off and tumour cell lysis are required for efficient priming. Intracellular IFN-γ levels from priming cultures were assayed by ELISA (Fig. 5d). Increased IFN-γ secretion was seen in cultures containing DC loaded with reovirus, consistent with the development of a TH1 adaptive immune response. Although increased IFN-γ was also found in cultures containing non-loaded mDC, this was not linked to adaptive anti-tumour priming, consistent with a requirement for tumour lysis and antigen release.

Figure 5.

Reovirus at 0 or 10 pfu/cell, or DC or T cells loaded at 0 or 10 pfu/cell were cultured with Mel-888 cells for 24 h and used to prime autologous PBMC. CTL were then used in a CD107 assay (a); graph shows mean ± SE of data from 5 independent experiments. (b) autologous PBMC were primed as in (a) but with blocking human serum added to the Mel-888 cells during co-culture with reovirus or carrier cells. Graph shows mean ± SE of data from 5 independent experiments;  denotes significance p < 0.05 between iDC or mDC and T cells or reovirus. (c) Representative plots showing CD107 degranulation by CD8 cells from priming cultures, against Mel-888 (relevant) or SKOV (irrelevant) targets. (d) Supernatants from priming cultures were analyzed for IFN-γ by ELISA; graph shows mean ± SE of data from 5 independent experiments.

denotes significance p < 0.05 between iDC or mDC and T cells or reovirus. (c) Representative plots showing CD107 degranulation by CD8 cells from priming cultures, against Mel-888 (relevant) or SKOV (irrelevant) targets. (d) Supernatants from priming cultures were analyzed for IFN-γ by ELISA; graph shows mean ± SE of data from 5 independent experiments.

Discussion

There is currently little effective therapy for metastatic melanoma and new approaches are urgently required. Oncolytic viruses are currently under investigation as a novel therapy for the disease. Among recent clinical trials, intratumoural injection of HSV has shown promising results(33) and reovirus is also potentially useful in melanoma(34). However, while skin lesions are readily accessible for direct viral injection, oncolytic viral therapy is seriously curtailed by an immune response if given systemically. Hence, novel delivery mechanisms which protect virus from neutralization by the immune system are required. Among the cell types that are competent for viral delivery to tumours, it has recently been demonstrated that DC can deliver reovirus for the clearance of melanoma metastases from the lymph nodes of reovirus-immune mice, and in this model DC were more efficient than T cells over a range of viral loads(21). Therefore, in this study, human DC were investigated as potential carriers for the therapeutic delivery of reovirus.

Human DC and T cells were able to deliver reovirus for melanoma killing in the absence of human blocking serum. By contrast, only iDC or mDC acted as efficient cell carriers in the presence of neutralizing serum, and delivered the virus for melanoma killing, albeit with lower efficacy than in the absence of serum. We have previously shown in mice that mDC, but not iDC, act as carriers for reovirus delivery in reovirus-immune animals. This may be linked to the significant level of reovirus replication seen in murine iDC(21), with the resulting high levels of cellular reovirus contributing to the detection and elimination of infected iDC by the immune system during trafficking. The absence of reovirus replication in human iDC or mDC might therefore aid immune evasion during therapy by preventing elimination of the cells as a result of immune targeting or direct reovirus-mediated toxicity. The difference in efficacy between human and murine iDC as reovirus carriers, highlights the importance of studies using human models to inform clinical trials.

The differing abilities of human T cells and DC to deliver reovirus to tumour targets in the presence of neutralizing serum, suggested that the virus might be differently localized on the carrier cells. It seemed possible that DC might internalize reovirus prior to delivery to tumour cells. Electron microscopy indicated that this was indeed the case, with reovirus being located at the surface of T cells where it would be susceptible to neutralizing antibodies, whereas significant levels of virus were detected internally in the DC and thus presumably protected from elimination. This is an important finding with regard to the systemic delivery of reovirus, but may also have implications for therapy with other oncolytic viruses, because even if patients have had no prior exposure to the therapeutic virus, antibody titres increase rapidly following the first dose(14) complicating multiple dosing strategies. Internalization of virus by DC is likely to be an important factor in determining their value as carriers for the systemic administration of oncolytic viruses.

In addition to a role as passive carrier cells for the delivery of reovirus for oncolysis, DC may also improve therapy by priming both innate and adaptive anti-tumour immunity. In the mouse, long-term purging of metastases correlated with induction of adaptive tumour specific immunity(21). In addition, human in vitro innate tumour cell killing by both NK cells and T cells can be induced by reovirus-activated DC(20, 35). The current study shows that reovirus-loaded DC, cultured with melanoma cells, could effectively prime specific anti-tumour immunity. Tumour-resident DC are often functionally impaired(32); therefore, the ability of reovirus-loaded carrier DC to prime specific CTL, indicates an important potential contribution to effective cancer immunotherapy in addition to direct oncolysis.

One criticism of oncolytic viral therapy is that any immune response generated will be predominantly against the virus rather than the tumour. Although the induction of anti-viral immunity was not examined in the current study, it is significant that a) specific anti-tumour immunity could be generated in the presence of reovirus, and b) that reovirus-loaded DC were competent for adaptive anti-tumour immune priming. The current data does not clearly indicate whether iDC or mDC would be preferable for human application; neither type of DC was clearly superior for viral hand-off/tumour cytotoxicity or for support of adaptive priming in the presence of neutralizing serum. For clinical studies iDC, without the use of an additional maturation signal, therefore appears to be a reasonable, straightforward choice.

The delivery of reovirus via cell carriage on DC could be a promising new development in systemic reoviral therapy for metastatic disease, both by efficient delivery of virus for tumour cell lysis in the presence of neutralizing antibodies and by generation of adaptive anti-tumour immunity. Furthermore, DC delivery may also be applicable to other oncolytic viruses and is worthy of further research and consideration in the design of future clinical trials.

Translational Relevance.

Oncolytic viruses are under clinical trial but their efficacy may be seriously curtailed by an immune response if they are given systemically. It has been shown that dendritic cells (DC) are effective for reovirus delivery to tumours in mice in the presence of neutralizing antibodies. This article shows that this seems also to be true for human DC and demonstrates that the biological basis for this is internalization of the virus by the DC thus protecting it from neutralization. Furthermore, reovirus-loaded DC are fully functional with regard to phagocytosis and immune priming. Thus, the use of DC to transport virus offers the possibility of combining viral delivery with induction of an anti-tumour immune response, as oncolysis by the viral payload will release tumour antigens for uptake by DC.

Acknowledgements

We thank Oncolytics Biotech for providing reovirus.

Grant Support

This work was funded by Cancer Research UK, and by the Paul Family Gift, the Richard M. Schulze Family Foundation, the Mayo Foundation and by NIH Grants CA RO1107082-02 and RO1130878.

Footnotes

Potential Conflict of interest

M. Coffey is an employee of Oncolytics Biotech.

References

- 1.Kirn DH, Thorne SH. Targeted and armed oncolytic poxviruses: a novel multi-mechanistic therapeutic class for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nrc2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comins C, Heinemann L, Harrington K, Melcher A, De Bono J, Pandha H. Reovirus: Viral Therapy for Cancer ‘as Nature Intended’. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aghi M, Martuza RL. Oncolytic viral therapies - the clinical experience. Oncogene. 2005;24:7802–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parato KA, Senger D, Forsyth PA, Bell JC. Recent progress in the battle between oncolytic viruses and tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:965–76. doi: 10.1038/nrc1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benencia F, Courreges MC, Fraser NW, Coukos G. Herpes virus oncolytic therapy reverses tumor immune dysfunction and facilitates tumor antigen presentation. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1194–205. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.8.6216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grunewald K, Lyons J, Frohlich A, Feichtinger H, Weger RA, Schwab G, et al. High frequency of Ki-ras codon 12 mutations in pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Int J Cancer. 1989;43:1037–41. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bos JL, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Verlaan-de Vries M, van Boom JH, van der Eb AJ, et al. Prevalence of ras gene mutations in human colorectal cancers. Nature. 1987;327:293–7. doi: 10.1038/327293a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemoine NR, Mayall ES, Wyllie FS, Farr CJ, Hughes D, Padua RA, et al. Activated ras oncogenes in human thyroid cancers. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4459–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodenhuis S, Slebos RJ, Boot AJ, Evers SG, Mooi WJ, Wagenaar SS, et al. Incidence and possible clinical significance of K-ras oncogene activation in adenocarcinoma of the human lung. Cancer Res. 1988;48:5738–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Needleman SW, Kraus MH, Srivastava SK, Levine PH, Aaronson SA. High frequency of N-ras activation in acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 1986;67:753–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams DJ, Ridinger DN, Spendlove RS, Barnett BB. Protamine precipitation of two reovirus particle types from polluted waters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;44:589–96. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.3.589-596.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minuk GY, Paul RW, Lee PW. The prevalence of antibodies to reovirus type 3 in adults with idiopathic cholestatic liver disease. J Med Virol. 1985;16:55–60. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890160108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tai JH, Williams JV, Edwards KM, Wright PF, Crowe JE, Jr., Dermody TS. Prevalence of reovirus-specific antibodies in young children in Nashville, Tennessee. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1221–4. doi: 10.1086/428911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White CL, Twigger KR, Vidal L, De Bono JS, Coffey M, Heinemann L, et al. Characterization of the adaptive and innate immune response to intravenous oncolytic reovirus (Dearing type 3) during a phase I clinical trial. Gene therapy. 2008;15:911–20. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai V, Johnson DE, Rahman A, Wen SF, LaFace D, Philopena J, et al. Impact of human neutralizing antibodies on antitumor efficacy of an oncolytic adenovirus in a murine model. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7199–206. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Yu DC, Charlton D, Henderson DR. Pre-existent adenovirus antibody inhibits systemic toxicity and antitumor activity of CN706 in the nude mouse LNCaP xenograft model: implications and proposals for human therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:1553–67. doi: 10.1089/10430340050083289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiao J, Kottke T, Willmon C, Galivo F, Wongthida P, Diaz RM, et al. Purging metastases in lymphoid organs using a combination of antigen-nonspecific adoptive T cell therapy, oncolytic virotherapy and immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2007 doi: 10.1038/nm1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iankov ID, Blechacz B, Liu C, Schmeckpeper JD, Tarara JE, Federspiel MJ, et al. Infected cell carriers: a new strategy for systemic delivery of oncolytic measles viruses in cancer virotherapy. Mol Ther. 2007;15:114–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Power AT, Wang J, Falls TJ, Paterson JM, Parato KA, Lichty BD, et al. Carrier Cell-based Delivery of an Oncolytic Virus Circumvents Antiviral Immunity. Mol Ther. 2007;15:123–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Errington F, Steele L, Prestwich R, Harrington KJ, Pandha HS, Vidal L, et al. Reovirus activates human dendritic cells to promote innate antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2008;180:6018–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ilett EJ, Prestwich RJ, Kottke T, Errington F, Thompson JM, Harrington KJ, et al. Dendritic cells and T cells deliver oncolytic reovirus for tumour killing despite pre-existing anti-viral immunity. Gene therapy. 2009;16:689–99. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.West E, Morgan R, Scott K, Merrick A, Lubenko A, Pawson D, et al. Clinical grade OK432-activated dendritic cells: in vitro characterization and tracking during intralymphatic delivery. J Immunother. 2009;32:66–78. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31818be071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Betts MR, Brenchley JM, Price DA, De Rosa SC, Douek DC, Roederer M, et al. Sensitive and viable identification of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells by a flow cytometric assay for degranulation. J Immunol Methods. 2003;281:65–78. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barton ES, Forrest JC, Connolly JL, Chappell JD, Liu Y, Schnell FJ, et al. Junction adhesion molecule is a receptor for reovirus. Cell. 2001;104:441–51. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paul RW, Choi AH, Lee PW. The alpha-anomeric form of sialic acid is the minimal receptor determinant recognized by reovirus. Virology. 1989;172:382–5. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foged C, Brodin B, Frokjaer S, Sundblad A. Particle size and surface charge affect particle uptake by human dendritic cells in an in vitro model. Int J Pharm. 2005;298:315–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rappocciolo G, Jenkins FJ, Hensler HR, Piazza P, Jais M, Borowski L, et al. DC-SIGN is a receptor for human herpesvirus 8 on dendritic cells and macrophages. J Immunol. 2006;176:1741–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lozach PY, Burleigh L, Staropoli I, Navarro-Sanchez E, Harriague J, Virelizier JL, et al. Dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN)-mediated enhancement of dengue virus infection is independent of DC-SIGN internalization signals. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23698–708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Witte L, Abt M, Schneider-Schaulies S, van Kooyk Y, Geijtenbeek TB. Measles virus targets DC-SIGN to enhance dendritic cell infection. Journal of virology. 2006;80:3477–86. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3477-3486.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halary F, Amara A, Lortat-Jacob H, Messerle M, Delaunay T, Houles C, et al. Human cytomegalovirus binding to DC-SIGN is required for dendritic cell infection and target cell trans-infection. Immunity. 2002;17:653–64. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00447-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geijtenbeek TB, Kwon DS, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Middel J, et al. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell. 2000;100:587–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vicari AP, Caux C, Trinchieri G. Tumour escape from immune surveillance through dendritic cell inactivation. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:33–42. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Senzer NN, Kaufman HL, Amatruda T, Nemunaitis M, Reid T, Daniels G, et al. Phase II Clinical Trial of a Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor-Encoding, Second-Generation Oncolytic Herpesvirus in Patients With Unresectable Metastatic Melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.3675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Errington F, White CL, Twigger KR, Rose A, Scott K, Steele L, et al. Inflammatory tumour cell killing by oncolytic reovirus for the treatment of melanoma. Gene therapy. 2008;15:1257–70. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prestwich RJ, Errington F, Steele LP, Ilett EJ, Morgan RS, Harrington KJ, et al. Reciprocal Human Dendritic Cell-Natural Killer Cell Interactions Induce Antitumor Activity Following Tumor Cell Infection by Oncolytic Reovirus. J Immunol. 2009 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]