Abstract

Summary

Background and objectives

To determine whether warfarin prolongs the time to first mechanical-catheter failure.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This was a multicenter parallel-group randomized controlled trial with blinding of participants, trial staff, clinical staff, outcome assessors, and data analysts. Randomization was in a 1:1 ratio in blocks of four and was concealed by use of fax to a central pharmacy. Hemodialysis patients with newly-placed catheters received low-intensity monitored-dose warfarin, target international normalized ratio (INR) 1.5 to 1.9, or placebo, adjusted according to schedule of sham INR results. The primary outcome was time to first mechanical-catheter failure (inability to establish a circuit or blood flow less than 200 ml/min).

Results

We randomized 174 patients: 87 to warfarin and 87 to placebo. Warfarin was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.90 (P = 0.60; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.57, 1.38) for time to first mechanical-catheter failure. Secondary analyses were: time to first guidewire exchange or catheter removal for mechanical failure (HR 0.78; 95% CI, 0.37, 1.6); time to catheter removal for mechanical failure (HR 0.67; 95% CI, 0.19, 2.37); and time to catheter removal for any cause (HR 0.89; 95% CI, 0.42, 1.81). Major bleeding occurred in 10 participants assigned to warfarin and seven on placebo (relative risk, 1.43; 95% CI, 0.57, 3.58; P = 0.61).

Conclusions

We found no evidence for efficacy of low-intensity, monitored-dose warfarin in preventing mechanical-catheter failure.

Introduction

Central-venous catheters have become a mainstay of dialysis access: their prevalence in the United States access mix has increased from 10 to 30% over the past 10 years (1). Catheters fail for a variety of reasons, including malposition, infection, and thrombosis (2): the most common reason for failure is mechanical, i.e. failure to sustain a blood pump speed adequate for dialysis (3,4). After a successful first use, thrombosis accounts for most mechanical failure (5,6). Fewer than half of catheters are still usable 1 year after placement (7).

Systemic anticoagulation to prevent catheter thrombosis has been recommended by experts in the field (8,9). However, direct evidence has been lacking, and a 2007 Cochrane review of patients with central-venous catheters for management of cancer found that treatment with vitamin K antagonists did not reduce the risk of symptomatic deep venous thrombosis (10). A 2008 review of studies in hemodialysis patients with central-venous catheters concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend routine administration of warfarin to prevent thrombosis or malfunction and noted the paucity of information on the safety of warfarin in this context (11).

We hypothesized that warfarin, started within 72 hours of catheter placement and adjusted to maintain international normalized ratio (INR) 1.4 to 1.9, would prolong the time to first mechanical catheter failure at the expense of an increase in risk of major and minor bleeding and planned a randomized trial to test this.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The study setting was two university hospitals and one community hospital. The inclusion criteria were: hemodialysis dependent or to start hemodialysis, with double-lumen tunneled or untunneled central-venous catheters, subclavian or jugular position, within 72 hours (up to 2 weeks for well-functioning catheters at the discretion of the site investigator) of initial placement or of guidewire exchange. The exclusion criteria were: major bleeding in the previous 3 months (bleeding requiring transfusion, bleeding in a critical site [retroperitoneal or intracranial], bleeding associated with hypovolaemia or requiring admission to hospital, and bleeding resulting in greater than a 20 g/L drop in hemoglobin concentration); persistent thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 50 × 109/L) or coagulopathy (e.g. known severe liver disease, hemophilia, or baseline INR >1.5); active peptic ulcer disease; need for further invasive investigation or intervention; warfarin anticoagulation for another indication; allergy or intolerance to warfarin; pregnancy and women of child-bearing age not using (or prepared to use) a form of effective contraception; inability to take oral medications; catheters with anticipated duration of use less than 2 weeks; previous participation in this study; known aortic aneurysms (≥6 cm); lack of agreement of clinical nephrologist; and inability to give or lack of informed consent.

A research ethics boards of participating institutions approved the study, and an independent clinical expert provided data safety monitoring.

Intervention

We randomized patients in a 1:1 ratio in blocks of four, stratified by center, by tunneled versus untunneled catheter and by whether patients were taking antiplatelet agents (aspirin, clopidogrel, or ticlopidine) at baseline. Antiplatelet agents were not stopped but continued during the study in patients taking warfarin and patients taking placebo at the discretion of the patients' clinical nephrologist. Heparin was used for catheter locking according to local institutional practice at concentrations between 1000 and 10,000 units/ml. A central research pharmacy ensured concealment by providing the drug and an identical-appearing placebo in numbered containers on the basis of a computer-generated random number sequence. Participants, clinical staff, outcome assessors, investigators, research coordinators, and data managers were blinded throughout. At each center, an unblinded warfarin monitor reported to study personnel true INRs for people on warfarin and sham INRs (from a pregenerated schedule of plausible results) for people on placebo. INRs were measured weekly and doses adjusted according to an algorithm.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was time to intervention for first mechanical catheter failure (inability to establish a circuit or pump speed less than 200 ml/min) not caused by kinking or extrusion. We chose a low pump threshold to increase the credibility of the outcome. Three planned secondary outcomes were: guidewire exchange or catheter removal for mechanical failure, catheter removal for mechanical catheter failure, and catheter removal for any cause. The patients were followed monthly until the catheter was removed or no longer needed. We continued to follow patients after guidewire exchange to a new catheter at the same site for the catheter removal outcomes. We continued active study drug until the end of the study for that patient or until the study drug was discontinued by the investigators, clinical team, or patient, and recorded the reasons for discontinuations. We recorded thrombolytic use, other interventions to restore catheter patency, episodes of bacteraemia (positive blood culture), exit-site infection (clinically identified and treated exit-site infection), major and minor bleeding, dialysis flow rates, and urea reduction ratios.

Analysis

We used Cox proportional hazards, stratified by antiplatelet agent, to examine the effect of warfarin assignment on outcomes. We used the intention-to-treat principle and censored data when a catheter was removed for reasons other than mechanical failure and if a catheter was no longer observed (e.g. not needed because of definitive access, transfer to peritoneal dialysis, recovery of renal function, or transplantation). We also performed an on-treatment analysis for each of the four efficacy outcomes, censoring data after permanent discontinuation of warfarin.

We performed a planned observational analysis of the association between use of antiplatelet agent at baseline with the four catheter survival outcomes. We used Fisher's exact test for categorical outcomes (e.g. bleeding, infections) and t tests for continuous outcomes (e.g. urea reduction ratios and blood flows). We examined the interaction between assignment to warfarin or placebo and use of antiplatelet agents at baseline on efficacy (Cox regression) and on safety (log-linear). We regarded P ≤ 0.05 as statistically significant, with the exception of the test for interaction between warfarin and antiplatelet agents (P ≤ 0.1). We used SPSS v15.0 and v17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The data analysts remained blinded throughout the analysis, and the steering committee interpreted the data before the randomization code was broken.

A planned sample size of 170 gave 80% power to detect a 40% relative risk reduction in mechanical-catheter failure. An independent statistician with expertise in methodology and the conduct of randomized trials performed one planned interim analysis after the randomization of 135 patients and recommended continuation of the trial. The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, which had no role in the conduct of the study.

Results

Between January 1999 and January 2007, we identified 174 patients who met the inclusion criteria, did not have exclusion criteria, and provided consent. Of these, 87 were allocated to warfarin, and 87 were allocated to a matching placebo capsule. The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants, by assignment to warfarin or to placebo

| Warfarin (n = 87) | Placebo (n = 87) | All (n = 174) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year (means; SD) | 62.4 (14.3) | 60.7 (16.7) | 61.6 (15.5) |

| Sex, male (n; %) | 48 (55.2) | 50 (57.5) | 98 (56.3) |

| Weight, kg (means; SD) | 79.8 (21.9) | 76.6 (19.6) | 78.3 (20.8) |

| Height, cm (means; SD) | 165.9 (11.1) | 165.8 (11.1) | 165.9 (11.1) |

| Hemoglobin, g/L (means; SD) | 98.4 (16.4) | 102.8 (16.9) | 100.6 (16.7) |

| INR (means; SD) | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.2) |

| Platelet count, × 109/L (means; SD) | 248.7 (80.5) | 243.3 (80.4) | 245.9 (80.3) |

| Calcium, mmol/L (means; SD) | 2.2 (0.3) | 2.1 (0.3) | 2.2 (0.3) |

| Cholesterol, mmol/L (means; SD) | 4.2 (1.4) | 4.4 (1.3) | 4.3 (1.3) |

| Protein, g/L (means; SD) | 65.1 (7.5) | 64.4 (8.0) | 64.8 (7.8) |

| Albumin, g/L (means; SD) | 33.8 (6.1) | 33.3 (6.0) | 33.6 (6.0) |

| Left-sided catheter (n; %) | 8 (9.2) | 6 (6.9) | 14 (8.0) |

| Subclavian catheter (n; %) | 8 (9.2) | 7 (8.0) | 15 (8.6) |

| Untunneled catheter (n; %) | 20 (23.0) | 22 (25.3) | 42 (24.1) |

| Rethreaded catheter (n; %) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (5.7) | 6 (3.4%) |

| Catheter manufacturer (n; %) | |||

| Vascath | 14 (18.2) | 17 (22.1) | 31 (20.1) |

| Cook | 5 (6.5) | 6 (7.8) | 11 (7.1) |

| Bard | 2 (2.6) | 2 (2.6) | 4 (2.6) |

| other | 56 (72.7) | 52 (67.5) | 108 (70.1) |

| Catheter tip position (n; %) | |||

| innominate | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) |

| SVC | 38 (43.7) | 40 (46.0) | 78 (44.8) |

| right atrium | 25 (28.7) | 29 (33.3) | 54 (31.0) |

| junction of SVC and right atrium | 21 (24.1) | 14 (16.1) | 35 (20.1) |

| unknown | 2 (2.3) | 3 (3.4) | 5 (2.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus, yes (n; %) | 48 (55.2) | 46 (52.9) | 94 (54.0) |

| Atrial fibrillation (n; %) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (5.7) | 6 (3.4) |

| Previous VTE (n; %) | 3 (3.4) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (2.3) |

| Valvular heart disease (n; %) | 5 (5.7) | 5 (5.7) | 10 (5.7) |

| Moderate or severe IHD (n; %) | 16 (18.4) | 18 (20.7) | 34 (19.5) |

| Moderate or severe CHF (n; %) | 20 (23.0) | 17 (19.5) | 37 (21.3) |

| Allergies to medications (n; %) | 28 (32.2) | 29 (33.3) | 57 (32.8) |

| Current smoking (n; %) | 10 (11.5) | 16 (18.4) | 26 (14.9) |

| Anti-platelet medications at baseline (n; %) | 37 (43) | 38 (44) | 75 (43%) |

| Centre (n; %) | |||

| Hamilton | 54 (62.1) | 54 (62.1) | 108 (62.1) |

| Halifax | 19 (21.8) | 18 (20.7) | 37 (21.3) |

| St. Catharines | 14 (16.1) | 15 (17.2) | 29 (16.7) |

Missing data: 0% for discrete variables except manufacturer, 12%. For continuous variables, missing data were 0 to 15% with the exception of cholesterol, 34%. SVC, superior vena cava; VTE, venous thromboembolism (history of deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism); diabetes mellitus, type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus; IHD, ischemic heart disease; CHF, congestive heart failure.

Patients assigned to warfarin were followed for median 4.8 months, interquartile range (IQR) 8.8, and a total of 722 participant-months, and those assigned to placebo were followed for median 4.0 months, IQR 7.4, and a total of 709 participant-months. The time on study drug (from assignment to permanent discontinuation) was median 3.3 months, IQR 5.1, and a total of 457 participant-months and median 3.0 months, IQR 5.8, and a total of 491 participant-months, respectively. No patient was lost to follow-up (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram showing entry into trial and subsequent disposition of participants and nonparticipants.

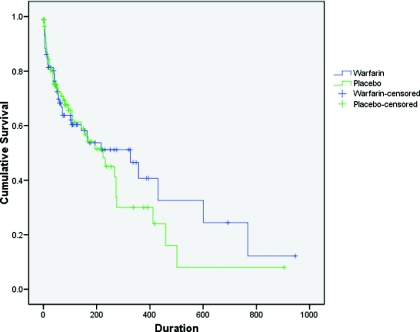

Over the course of the study 81 of 174 participants met the primary outcome of first intervention for catheter malfunction: 40 of 87 assigned to warfarin and 41 of 87 assigned to placebo (hazard ratio [HR], stratified for use of antiplatelet agents at baseline, 0.90; 95% confidence intervals [CI] 0.57, 1.38; P = 0.60; Table 2 and Figure 2). Of these primary outcomes, 16 (19.8%) were inability to establish a circuit, 50 (61.7%) had flows less than 200 ml/min, and 15 (18.5%) were tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) initiated by clinical staff, who were blinded to allocation, for situations that did not appear to meet prespecified criteria (eight of 40 outcomes in the patients allocated to warfarin and seven of 41 outcomes in patients allocated to placebo). A committee evaluated each of these protocol violations individually and classified seven as reasonable (e.g. blood flows persistently between 200 and 250 ml/min, unresponsive to line reversal, forceful flushing, and patient positioning), six as unreasonable, and two as unknown, on the basis of available data. There was not any difference in the proportion of protocol violations or unreasonable protocol violations in patients assigned to warfarin and those assigned to placebo (P = 0.78 and 0.48, respectively).

Table 2.

Summary of efficacy analyses: results of Cox regression (stratified by antiplatelet agent) for the primary and secondary analyses, by intention-to-treat and on-treatment

| Analysis | Intention-to-Treat |

On-Treatment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P | |

| First mechanical catheter failure | 0.90 | 0.57, 1.38 | 0.60 | 0.88 | 0.54, 1.43 | 0.62 |

| First guidewire exchange or catheter removal for mechanical failure | 0.78 | 0.37, 1.61 | 0.50 | 0.82 | 0.34, 1.98 | 0.66 |

| Catheter removal for mechanical failure | 0.67 | 0.19, 2.37 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.04, 5.43 | 0.56 |

| Catheter removal for any reason | 0.87 | 0.42, 1.81 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.15, 1.66 | 0.26 |

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plot of time to first mechanical-catheter failure, the primary outcome, analyzed by the intention-to-treat principle (P = 0.60).

Analyses of secondary outcomes of time to first guidewire exchange or catheter removal for mechanical failure, time to catheter removal for mechanical failure, and time to catheter removal for any indications showed no statistically significant differences (Table 2). Censoring at the time of permanent discontinuation of warfarin did not substantially alter the results (Table 2).

The interaction between assignment to warfarin and use of antiplatelet agents at baseline was not statistically significant in all eight efficacy analyses (P ≥ 0.272 in all patients). At the start of the study, 75 participants were taking antiplatelet agents, 37 of 87 allocated to warfarin (43%) and 38 of 87 allocated to placebo (44%). Use of antiplatelet drugs at baseline was associated with a tendency toward benefit in the primary outcome that did not reach statistical significance (HR 0.68; 95% CI, 0.43, 1.08; P = 0.11); confidence intervals for secondary outcomes were wide (data not shown).

There were 12 major bleeds in 10 of 87 (11.5%) participants allocated to warfarin and seven major bleeds in seven of 87 (8%) participants allocated to placebo (relative risk [RR], 1.43; 95% CI, 0.57, 3.58; P = 0.61) and 37 major or minor bleeds in 26 of 87 (29.9%) participants allocated to warfarin and 22 major or minor bleeds in 18 of 87 (20.7%) participants allocated to placebo (RR, 1.44; 95% CI, 0.86, 2.44; P = 0.22). There were nine major bleeds in nine of 75 (12.0%) participants receiving antiplatelet agents and 10 major bleeds in eight of 99 (8.1%) participants not receiving antiplatelet agents (RR, 1.49; 95% CI, 0.62, 3.59; P = 0.45) and 21 major or minor bleeds in 19 of 75 (25.3%) participants receiving antiplatelet agents and 38 major or minor bleeds in 25 of 99 (25.3%) participants not receiving antiplatelet agents (RR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.60, 1.67; P = 1.00). There was no significant interaction between warfarin assignment and use of antiplatelet agent on the risk of major or any bleeding (P = 0.70 and 0.67, respectively). Of 12 major bleeds in patients assigned to warfarin, seven occurred while on the study drug, of which three occurred with therapeutic INR, three occurred with high INR (2.0, 3.0, and 10.0), and the INR in one was unknown.

There were five deaths in 87 (5.7%) participants assigned to warfarin and eight in 87 (9.2%) assigned to placebo (P = 0.57). Fatal bleeding (bleeding that was a major contributor to death) occurred in three of 87 (3.4%) and one of 87 (1.1%), respectively (P = 0.62). The reasons for discontinuation of warfarin are shown in figure 1.

Urea reduction ratios and mean blood flow (total blood processed divided by recorded treatment time) were monitored every 2 weeks. There was not any difference between assigned groups. Mean urea reduction ratio was 66.0 (95% CI, 64.0, 68.0) in participants allocated to warfarin and 65.9 (95% CI, 64.2, 67.6) in participants on placebo (P = 0.92); mean blood flow was 305 ml/min (95% CI, 293, 318) and 307 ml/min (95% CI, 295, 320) respectively (P = 0.83). Antiplatelet agent use at baseline was not associated with urea-reduction ratio or with blood flow during the study (P = 0.49 and 0.74, respectively).

Bacteremia occurred 14 times in 12 of 87 participants allocated to warfarin and five times in five of 87 participants on placebo (RR, 2.40; 95% CI, 0.88, 6.52; P = 0.12); exit-site infection occurred 36 times in 19 of 87 participants allocated to warfarin and 31 times in 24 of 87 participants on placebo (RR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.47, 1.34; P = 0.48).

Discussion

In a trial of 174 patients allocated to warfarin or to matching placebo, we found no evidence of efficacy of anticoagulation to a target INR 1.5 to 1.9. The study used concealed randomization and blinding of participants, researchers, and clinicians, prespecified outcomes, with no loss to follow-up, and analysis according to the intention-to-treat principle. The breadth of the inclusion criteria enhances the generalizability of results, borne out by the age and comorbidity in participants. Our data do not suggest that warfarin is effective prophylaxis against catheter malfunction.

This is the largest trial to date in people with end-stage renal disease to randomize patients to warfarin or placebo for any indication. Although it is possible that warfarin might be more effective if started the day of insertion, if patients received bridging heparin anticoagulation until the INR is therapeutic, or if a higher INR range had been examined, the absence of any tendency toward benefit in either intention-to-treat or on-treatment analyses argues for true lack of effect.

Four previous prospective studies examined oral anticoagulation with warfarin in the prevention of catheter malfunction. Warfarin (1 mg daily) was ineffective in a randomized trial of 85 patients, although there was a decrease in thrombosis in the subgroup that achieved INR greater than 1.0 (12). An observational study in which 35 patients with previous catheter malfunction were anticoagulated to INR 1.5 to 2.0 and compared with 35 controls showed a trend toward lower rates of malfunction in the anticoagulated patients, particularly in those in whom anticoagulation targets were met (13). A prospective observational study of 62 patients showed fewer episodes of thrombosis with warfarin (INR 2.0 to 3.0) compared with no therapy (14). Finally, in a randomized trial of 144 patients by Coli et al. (15), patients were treated with ticlopidine and randomized to receive warfarin (INR 1.8 to 2.5) combined with low molecular weight heparin until the INR was therapeutic or to no additional treatment, starting within 12 hours of central–venous-catheter insertion. At 1 year, 12% of anticoagulated and 52% of control patients had experienced a thrombosis (P < 0.01), an absolute risk reduction of 40%. Compared with these studies, ours used a randomized design, is the largest to date, and used concealed allocation, blinding of patient, clinical team, investigators, and outcome adjudicators. Our finding of no effect may reflect more rigorous design. Type II error is also possible. We had 80% power to detect a risk reduction of 40%: power for detecting more modest but clinically-important differences was more limited. However, since the design and initiation of our study, lower-intensity anticoagulation has also been shown not to be effective prophylaxis for catheter malfunction in patients with cancer (16).

No randomized studies have examined the efficacy of anti-platelet agents in preventing mechanical malfunction of dialysis catheters, and our study is the largest observational study of this issue. For the primary outcome we observed a clinically-important effect size in favor of anti-platelet agents that did not reach statistical significance (HR = 0.68 [0.43, 1.08], P = 0.11). This tendency is in keeping with other nonrandomized observations in dialysis (14) and nondialysis patients (17).

Bleeding was common in our study, but the risk of bleeding attributable to warfarin was not prohibitive had the intervention been effective. We found 12 major bleeds in 722 months in participants assigned to warfarin (0.20 per patient-year) and seven in 709 months (0.12 per patient-year) in those assigned to placebo (rate ratio, 1.67); the relative risk associated with any major bleed was 1.43 (95% CI, 0.57, 3.58; P = 0.61). Confidence intervals are wide, but the point estimate is in line with the accumulating literature: absolute risk of bleeding of 0.10 to 0.54 per patient-year, and relative risk 1.46 to infinity have been reported (18–20). In the general population, lower targets for INR have been found to be no safer than target INR 2 to 3 (21,22). Our sample size is inadequate to determine whether the difference in fatal bleeding (three in the warfarin group versus one in the placebo group) resulted from chance. A retrospective study of hemodialysis patients, using administrative data, found a tendency toward increased risk of fatal bleeding associated with warfarin (HR, 1.77; 95% CI, 0.82 to 3.82) that did not reach statistical significance (20).

We recognize limitations to our work. Following the Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative 2000 guideline that defined adequate blood flow as 300 ml/min (23), the availability of catheter-locking doses of tPA (24) and the accumulating evidence of its efficacy (25), the use of tPA became more liberal in dialysis units, and some study patients who had not met study failure definitions were given tPA. It is unlikely that these protocol violations biased our results: (1) the number of protocol violations was low, 15 out of 81 events; (2) of these, seven occurred in situations where the severity of the catheter problem was well established; (3) the decisions were made by blinded clinical staff; (4) similar numbers of protocol violations occurred in each group; and (5) “need for tPA” is a reasonable outcome in itself. We considered a post-hoc analysis ignoring tPA administration that did not meet criteria but rejected this because of tPA restores catheter patency in about 90% of patients (25) and alters the clinical history of catheter survival. Second, discontinuation of study drug was high: 44 of 83 on warfarin and 34 of 82 on placebo, 47% overall. We believe this reflects the risks of anticoagulation and patients' and clinicians' perceptions of those risks. For example in a recent randomized trial in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, who are at much lower risk than the patients we studied, discontinuations occurred in 640 of 1962 patients assigned to warfarin (33%), albeit over a longer time period (26). Third, audit revealed that seven patients received incorrect monitoring: two participants on placebo were monitored as if on warfarin and five participants on warfarin were monitored as if on placebo. Of these five, four participants had INRs within the therapeutic or subtherapeutic range, one of whom experienced nonfatal major bleeding (INR 1.6 at time of bleed). The remaining patient was inappropriately prescribed an increase in warfarin dose when the true INR was supratherapeutic (because the sham INR was subtherapeutic), followed by nonfatal major bleeding with INR 10.0. Although warfarin monitors received training and support, this problem arose twice, illustrating the difficulties of conducting double-blind randomized trials of warfarin. This difficulty is acknowledged by the design of recent major randomized trials that have blinded other interventions but used open-label warfarin (27,28). Finally, our sample-size calculation was based on a large 40% reduction in events, which seemed plausible on the basis of available literature from other catheters. We cannot exclude a benefit of smaller magnitude, which might still be clinically important, or that our results are incorrect through the play of chance. However, all our results are internally congruent, with no curve separation in the first 200 days in either intention-to-treat or on-treatment analyses and no benefit in terms of secondary clinical outcomes or the surrogate outcomes of flow and urea-reduction ratio.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that low-intensity monitored-dose warfarin should not be used for primary prophylaxis in newly inserted dialysis catheters.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Catherine Clase, Alistair Ingram, Mark Crowther, and Kailash Jindal designed the study and obtained funding. Catherine Clase, Alistair Ingram, Steven Soroka, and Ryuta Ngai were principal site investigators. Trevor Wilkieson was lead study coordinator and data manager and performed the statistical analysis under the supervision of Catherine Clase. Alistair Ingram and Catherine Clase wrote the manuscript. All of the authors revised the manuscript. Catherine Clase is guarantor.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. We thank the nephrologists, patients, and clinical and research staff who participated, Robin Roberts for performing the blinded interim analysis, and Louise Moist for independent review of safety of trial participants. Mark Crowther holds a Career Investigator award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Catherine Clase is supported by her colleagues in the Division of Nephrology at McMaster University.

This work was presented at the Canadian Society of Nephrology Annual Meeting, Edmonton, May 2009.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1. United States Renal Data System USRDS 2004 Annual Data Report. Available at: www.usrds.org/adr.htm Accessed January 24, 2011

- 2. Liangos O, Gul A, Madias NE, Jaber BL: Long-term management of the tunneled venous catheter. Semin Dial 19: 158–164, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beathard GA: Catheter thrombosis. Semin Dial 14: 441–445, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Kidney Foundation KDOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Vascular Access 2006. Am J Kidney Dis 48[Suppl 1]: S176–S273, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Develter W, De CA, Van BW, Vanholder R, Lameire N: Survival and complications of indwelling venous catheters for permanent use in hemodialysis patients. Artificial Organs 29: 399–405, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Little MA, O'Riordan A, Lucey B, Farrell M, Lee M, Conlon PJ, Walshe JJ: A prospective study of complications associated with cuffed, tunnelled haemodialysis catheters. Nephrol Dial Transplant 16: 2194–2200, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ponikvar R, Buturovic-Ponikvar J: Temporary hemodialysis catheters as a long-term vascular access in chronic hemodialysis patients. Ther Apher Dial 9: 250–253, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pierratos A, Ouwendyk M, Francoeur R, Vas S, Raj DS, Ecclestone AM, Langos V, Uldall R: Nocturnal hemodialysis: Three-year experience. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 859–868, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Twardowski ZJ: High-dose intradialytic urokinase to restore the patency of permanent central vein hemodialysis catheters. Am J Kidney Dis 31: 841–847, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Akl EA, Yosuico VED, Kim SY, Barba M, Sperati F, Cook D, Schünemann HJ: Anticoagulation for thrombosis prophylaxis in cancer patients with central venous catheters. Cochrane Database Syst Rev DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006468.pub2.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Willms L, Vercaigne LM: Does warfarin safely prevent clotting of hemodialysis catheters? A review of efficacy and safety. Semin Dial 21: 71–77, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mokrzycki MH, Jean-Jerome K, Rush H, Zdunek MP, Rosenberg SO: A randomized trial of minidose warfarin for the prevention of late malfunction in tunneled, cuffed hemodialysis catheters. Kidney Int 59: 1935–1942, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zellweger M, Bouchard J, Raymond-Carrier S, Laforest-Renald A, Querin S, Madore F: Systemic anticoagulation and prevention of hemodialysis catheter malfunction. ASAIO J 51: 360–365, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Obialo CI, Conner AC, Lebon LF: Maintaining patency of tunneled hemodialysis catheters: Efficacy of aspirin compared to warfarin. Scand J Urol Nephrol 37: 172–176, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coli L, Donati G, Cianciolo G, Raimondi C, Comai G, Panicali L, Nastasi V, Cannarile DC, Gozzetti F, Piccari M, Stefoni S: Anticoagulation therapy for the prevention of hemodialysis tunneled cuffed catheters (TCC) thrombosis. J Vasc Access 7: 118–122, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Couban S, Goodyear M, Burnell M, Dolan S, Wasi P, Barnes D, Macleod D, Burton E, Andreou P, Anderson DR: Randomized placebo-controlled study of low-dose warfarin for the prevention of central venous catheter-associated thrombosis in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 23: 4063–4069, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Curigliano G, Balduzzi A, Cardillo A, Ghisini R, Peruzzotti G, Orlando L, Torrisi R, Dellapasqua S, Lunghi L, Goldhirsch A, Colleoni M: Low-dose aspirin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in breast cancer patients treated with infusional chemotherapy after insertion of central vein catheter. Supportive Care Cancer 15: 1213–1217, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elliott MJ, Zimmerman D, Holden RM: Warfarin anticoagulation in hemodialysis patients: A systematic review of bleeding rates. Am J Kidney Dis 50: 433–440, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Holden RM, Harman GJ, Wang M, Holland D, Day AG: Major bleeding in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 105–110, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chan K, Lazarus J, Thadhani R, Hakim R: Anticoagulant and antiplatelet usage associates with mortality among hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 872–881, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kearon C, Ginsberg JS, Kovacs MJ, Anderson DR, Wells P, Julian JA, MacKinnon B, Weitz JI, Crowther MA, Dolan S, Turpie AG, Geerts W, Solymoss S, van Nguyen P, Demers C, Kahn SR, Kassis J, Rodger M, Hambleton J, Gent M: Comparison of low-intensity warfarin therapy with conventional-intensity warfarin therapy for long-term prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 349: 631–639, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oake N, Jennings A, Forster AJ, Fergusson D, Doucette S, van Walraven C: Anticoagulation intensity and outcomes among patients prescribed oral anticoagulant therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 179: 235–244, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. National Kidney Foundation KDOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Vascular Access, 2000. Am J Kidney Dis 37[Suppl 1]: S137–S181, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wiernikowski JT, Crowther M, Clase CM, Ingram AJ, Andrew M, Chan AKC: Determination of stability and sterility of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) at −30° celsius. Lancet 335: 2221–2222, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Clase CM, Crowther MA, Ingram AJ, Cina CS: Thrombolysis for restoration of patency to haemodialysis central venous catheters: A systematic review. J Thromb Thrombolysis 11: 127–136, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Albers GW, Diener HC, Frison L, Grind M, Nevinson M, Partridge S, Halperin JL, Horrow J, Olsson SB, Petersen P, Vahanian A: Ximelagatran vs warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: A randomized trial. JAMA 293: 690–698, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J, Wang S, Alings M, Xavier D, Zhu J, Diaz R, Lewis BS, Darius H, Diener HC, Joyner CD, Wallentin L: Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 361: 1139–1151, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Massie BM, Collins JF, Ammon SE, Armstrong PW, Cleland JG, Ezekowitz M, Jafri SM, Krol WF, O'Connor CM, Schulman KA, Teo K, Warren SR: Randomized trial of warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel in patients with chronic heart failure: The Warfarin and Antiplatelet Therapy in Chronic Heart Failure (WATCH) trial. Circulation 119: 1616–1624, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]