Abstract

Summary

Background and objectives

Although percutaneous liver biopsy (PLB) is the gold standard for staging hepatic fibrosis in hemodialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) before renal transplantation or antiviral therapy, concerns exist about serious postbiopsy complications. Using transient elastography (TE, Fibroscan®) to predict the severity of hepatic fibrosis has not been prospectively evaluated in these patients.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

A total of 284 hemodialysis patients with CHC were enrolled. TE and aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) were performed before PLB. The severity of hepatic fibrosis was staged by METAVIR scores ranging from F0 to F4. Receiver operating characteristic curves were used to assess the diagnostic accuracy of TE and APRI, taking PLB as the reference standard.

Results

The areas under curves of TE were higher than those of APRI in predicting patients with significant hepatic fibrosis (≥F2) (0.96 versus 0.84, P < 0.001), those with advanced hepatic fibrosis (≥F3) (0.98 versus 0.93, P = 0.04), and those with cirrhosis (F4) (0.99 versus 0.92, P = 0.13). Choosing optimized liver stiffness measurements of 5.3, 8.3, and 9.2 kPa had high sensitivity (93–100%) and specificity (88–99%), and 87, 97, and 93% of the patients with a fibrosis stage of ≥F2, ≥F3, and F4 were correctly diagnosed without PLB, respectively.

Conclusions

TE is superior to APRI in assessing the severity of hepatic fibrosis and can substantially decrease the need of staging PLB in hemodialysis patients with CHC.

Introduction

Despite the introduction of blood product screening and universal precautions, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection remains a significant threat for hemodialysis patients. The annual incidence and prevalence rates of HCV infection range from 0.22 to 6.20% and 3.4 to 80%, respectively, by different geographic distributions (1–5). Although hemodialysis patients with chronic HCV infection are usually asymptomatic with mildly elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, previous studies indicate that they are at increased risk of liver-related morbidity and mortality, either at the dialysis or postrenal transplantation stage (6–8).

In clinical practice, assessing hepatic fibrosis for hemodialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) can help evaluate the eligibility for renal transplantation, the necessity for IFN-based therapy, the long-term prognosis, and complications related to portal hypertension and hepatocellular carcinoma (1,9–13), and percutaneous liver biopsy (PLB) is recognized as the gold standard to evaluate the severity of hepatic fibrosis (14,15). However, PLB is an invasive procedure with poor patient acceptance and, although rare, possible adverse events in hemodialysis patients (16–20). In addition, sampling and interpretation variability is frequently encountered, leading to the search for noninvasive means to assess the severity of hepatic fibrosis in these patients (21,22).

Recent studies have focused on using simple biochemical indices to predict the severity of hepatic fibrosis in uremic and nonuremic patients with CHC, and the aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) was considered useful (17,23–28). Nevertheless, studies for hemodialysis patients showed that the major strength of APRI was to exclude significant hepatic fibrosis, and only 50% patients could be correctly diagnosed (27,28). Therefore, efforts to improve the overall diagnostic accuracy through other noninvasive tools are needed.

Transient elastography (TE, Fibroscan®) is a novel noninvasive tool to assess the severity of hepatic fibrosis by liver stiffness measurement (LSM). TE can be easily performed in our daily practice with immediate results and good reproducibility (29–31). The performance of TE to evaluate the severity of hepatic fibrosis has been validated in nonuremic patients with CHC, showing good diagnostic accuracy in those with significant hepatic fibrosis (cut-off point: 7.1 and 8.8 kPa), and excellent diagnostic accuracy in those with advanced hepatic fibrosis (cut-off point: 9.5 and 9.6 kPa) or cirrhosis (cut-off point: 12.5 and 14.6 kPa) (31–33). However, little is known about the role of TE to assess the severity of hepatic fibrosis in hemodialysis patients with CHC. The aim of this study was to prospectively compare the diagnostic accuracy of TE and APRI for the severity of hepatic fibrosis in hemodialysis patients with CHC, taking PLB as the reference standard.

Materials and Methods

Patients

From July 2007 to March 2010, 304 consecutive hemodialysis patients with CHC aged between 18 and 65 years were prospectively enrolled at four academic centers in Taiwan. Hemodialysis patients with CHC were defined as patients with creatinine clearance of less than 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 of body surface area who received maintenance renal replacement therapy through vascular routes and were both positive for anti-HCV (Abbott HCV EIA 3.0, Abbott Diagnostic, Chicago, IL) and HCV RNA (Cobas TaqMan HCV Test v2.0; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany; detection limit: 15 IU/ml) for more than 6 months. Patients who had a history of hepatitis B virus or HIV coinfection, alcohol abuse, neoplic diseases, or other causes of liver diseases, received immunosuppressive agents, had decompensated cirrhosis, declined, or were contraindicated for PLB and failed to reach LSMs were excluded from this study. The study conformed to the principles of Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the institutional review board. Each participant gave written informed consent before enrollment.

Concise Methods

Baseline demographic data were collected for all patients. Hemogram (including hemoglobin, white blood cell count, and platelet count), coagulation profiles (prothrombin time), serum biochemical data (including albumin, total bilirubin, AST, ALT, and creatinine), serologic and virological data (anti-HCV, HBsAg, anti-HIV, HCV RNA, and HCV genotype), and gray-scaled abdominal ultrasonography were performed before PLBs. The hemogram and the routine biochemistry were evaluated by automated Sysmex XE-2100 hematology analyzer (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan) and Toshiba TBA-120 FR analyzer (Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan). HCV RNA and HCV genotyping (Inno-LiPA HCV II; Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium) were tested for all patients. The APRI was calculated as AST/upper limit of normal (ULN) × 100/platelet count (109/L) (23).

LSM was determined by TE (Fibroscan®, Echosens, Paris, France; detection range: 2.5 to 75 kPa) equipped with an M probe for patients after an overnight fasting of at least 8 hours. In addition, all patients received hemodialysis 1 day before LSMs to keep adequate dry weight. All LSMs were performed by four experienced operators (K. L. She, L. F. Wu, C. C. Chen, and Y. L. Tang) who had performed more than 500 LSMs. The procedure was done with the patients lying in a supine position with the right arm tucked behind the head to facilitate probe access. The tip of the probe was placed on the skin of the right intercostal space at the level of right hepatic lobe where PLB would be performed. The volume of LSM approximates a cylinder 4 cm long and 1 cm wide between 25 and 65 mm deep below the skin surface. The results of LSM were expressed in kPa with a median value of at least 10 valid measurements and a successful rate of more than 60%. LSM failure was defined as zero valid measurement, and unreliable examinations were defined as less than 10 valid measurements, a successful rate of less than 60%, or the interquartile range (IQR) more than 30% of the median LSM value (34).

After receiving blood tests and LSMs, all of the eligible patients underwent PLBs in 2 weeks. Ultrasound-guided liver biopsies from the right hepatic lobe were performed by 16-gauge biopsy needles (Temno Evolution, Allegiance, McGaw Park, IL). The sampling tissues were fixed with formalin and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and reticulin silver (Masson trichome method). The hepatic necroinflammation and fibrosis were assessed by the METAVIR scoring system, ranging from A0 to A3 and F0 to F4, respectively (35). Significant hepatic fibrosis, advanced hepatic fibrosis, and cirrhosis were defined as a fibrosis stage ≥F2, ≥F3, and F4. The hepatic steatosis was graded by AGA technical guidelines ranging from G0 to G3 (36). All of the histologic samples were evaluated by one experienced pathologist who was blinded to the clinical data of the patients.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed by the Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS 12.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Patient characteristics are expressed as the means ± SD and percentages when appropriate. The estimated sample sizes to compare receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves of TE and APRI in patients with a fibrosis stage ≥F2, ≥F3, and F4 were 280, 217, and 197, respectively, on the basis of the following assumptions: type I error = 0.05; type II error = 0.10; positive group correlation = 0.43 and negative group correlation = 0.50; the estimated areas under curves (AUCs) for TE and APRI = 0.89 and 0.83 for a fibrosis stage ≥F2, 0.93 and 0.87 for a fibrosis stage ≥F3, and 0.97 and 0.92 for a fibrosis stage = F4 (28,37). One-way ANOVA was used to compare the mean LSM by various fibrosis stages. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used to analyze the correlations between LSM and fibrosis stages. ROC curves for TE and APRI were constructed, and the AUCs of TE and APRI with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were compared by c-statistics for different fibrosis stages (37). The adjusted uniform AUC and the naturally-observed adjusted AUC were calculated by the regression formula for the difference between the mean fibrosis stage of advanced minus nonadvanced fibrosis (DANA) (30,38). The sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value, positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR+ and LR−), and diagnostic accuracy of LSM and APRI were determined by the known selected cut-off values (23,32,33). The optimized cut-off values were determined by the methods of the minimal (1 − sensitivity)2 + (1 − specificity)2 value and the Youden index defined as the maximal (sensitivity + specificity − 1). Univariate analyses of baseline factors to predict LSM accuracy for different fibrosis stages were performed by two-sample t test and χ2 with Fisher's exact test, followed by multivariate regression analysis when appropriate. All of the statistical tests were two-tailed, and the results were statistically significant when the p value was <0.05.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Of 304 patients, 20 were excluded from the study because of hepatitis B virus coinfection in six, hepatocellular carcinoma in two, decompensated cirrhosis in two, failed LSM in seven (2.3%), and declining PLB in three. Four patients had LSM failure (two with right hepatic lobe resection, one with body-mass index (BMI) = 31.3 kg/m2, and one with narrow intercostal space); three had unreliable measurements (two with BMI = 28.7 kg/m2 [IOR/LSM >30%] and 29.1 kg/m2 [<10 valid measurements] and one with narrow intercostal space [<10 valid measurements]). The liver biopsy complications included local pain in 52 (18.3%), shoulder soreness in 33 (11.7%), puncture site oozing in 32 (11.3%), intrahepatic hematoma in three (1.1%), and hemoperitoneum in one (0.4%). The baseline characteristics of the remaining 284 patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean serum AST and ALT levels were 1.0 ± 0.6 and 1.4 ± 1.3 times ULN. The mean length of biopsy samples was 18.1 ± 1.4 mm, and the mean number of portal tracts was 16 ± 5. Two-hundred thirty-eight patients (83.8%) had no or mild hepatic necroinflammation, 101 (35.6%) had significant hepatic fibrosis (≥F2), 40 (14.1%) had advanced hepatic fibrosis (≥F3), and 14 (4.9%) had cirrhosis (F4). Two-hundred fifty-one patients (88.4%) had no hepatic steatosis, 23 (8.1%) had grade 1 hepatic steatosis, and ten (3.5%) had grade 2 steatosis.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristics | Hemodialysis Patients with CHC (n = 284) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.4 ± 9.7 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 168 (59.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.5 ± 3.4 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 11.6 ± 1.8 |

| White blood cell count (× 109/L) | 6.4 ± 1.8 |

| Platelet count (× 109/L) | 193 ± 59 |

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 0.95 ± 0.21 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 4.1 ± 0.4 |

| Bilirubin total (mg/dl) | 0.4 ± 0.2 |

| AST (/ULN) | 1.0 ± 0.6 |

| ALT (/ULN) | 1.4 ± 1.3 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 10.0 ± 3.2 |

| HCV RNA, log10 (IU/ml) | 5.8 ± 0.8 |

| HCV genotype, n (%) | |

| 1a/1b | 181 (63.7) |

| 2a/2b | 101 (35.6) |

| 6 | 2 (0.7) |

| Indications for liver biopsy, n (%) | |

| renal transplantation | 38 (13.4) |

| anti-viral therapy | 246 (86.6) |

| Length of biopsy samples (mm) | 18.1 ± 1.4 |

| range of length (mm) | 13 to 30 |

| length >15 mm, n (%) | 271 (95) |

| length >25 mm, n (%) | 42 (15) |

| number of portal tracts | 16 ± 5 |

| Activity score (METAVIR), n (%) | |

| A0 | 27 (9.5) |

| A1 | 211 (74.3) |

| A2 | 43 (15.1) |

| A3 | 3 (1.1) |

| Fibrosis score (METAVIR), n (%) | |

| F0 | 81 (28.5) |

| F1 | 102 (35.9) |

| F2 | 61 (21.5) |

| F3 | 26 (9.2) |

| F4 | 14 (4.9) |

| Steatosis score | |

| G0 | 251 (88.4) |

| G1 | 23 (8.1) |

| G2 | 10 (3.5) |

| G3 | 0 (0) |

INR, international normalized ratio.

Correlation between LSM and METAVIR Fibrosis Scores

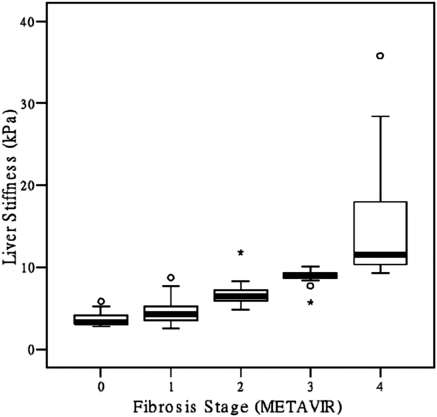

The mean LSM paralleled the advancing hepatic fibrosis: 3.6 ± 0.7 kPa (F0), 4.5 ± 1.3 kPa (F1), 6.6 ± 1.1 kPa (F2), 8.9 ± 0.9 kPa (F3), and 15.1 ± 7.8 kPa (F4) (P < 0.001). Figure 1 shows the box plots of LSM for each METAVIR fibrosis stage. The median LSM and the fibrosis stages were highly correlated: 3.3 kPa (2.8 to 5.8 kPa) (F0), 4.3 kPa (2.5 to 8.7 kPa) (F1), 6.4 kPa (4.8 to 11.8 kPa) (F2), 8.9 kPa (5.7 to 10.1 kPa) (F3), and 11.5 kPa (9.3 to 35.8 kPa) (F4) (r = 0.81, P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Box plots of LSM (kPa) for each METAVIR fibrosis stage (F0 to F4) in hemodialysis patients with CHC. The tops and bottoms of the boxes are the first and the third quartiles. The patient numbers with a hepatic fibrosis of F0, F1, F2, F3, and F4 were 81, 102, 61, 26, and 14, respectively.

Diagnostic Accuracy of TE and APRI in Patients with Significant Hepatic Fibrosis, Advanced Hepatic Fibrosis, and Cirrhosis

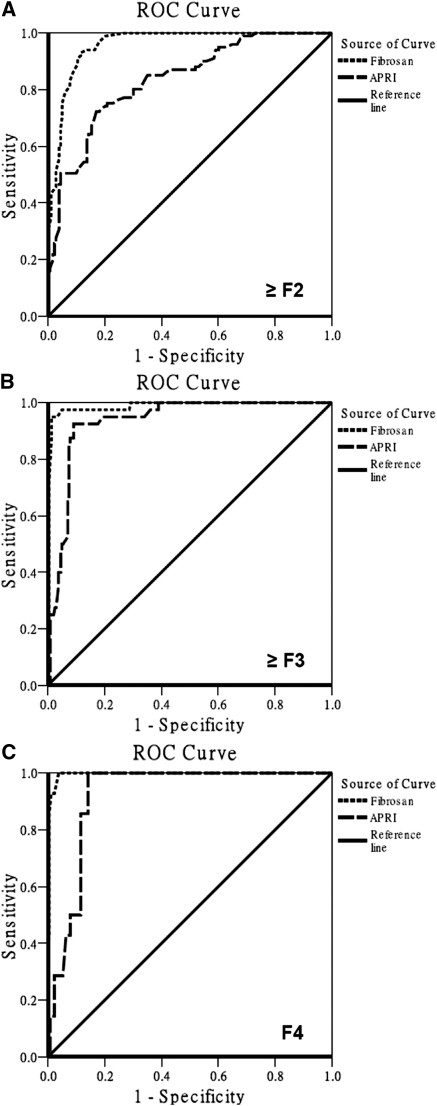

Figure 2 shows the diagnostic accuracy of TE and APRI to predict patients with significant hepatic fibrosis, advanced hepatic fibrosis, and cirrhosis. The AUC of TE was superior to that of APRI in patients with a fibrosis stage ≥F2 (0.96 [95% CI: 0.94 to 0.98] versus 0.84 [95% CI: 0.79 to 0.88], P < 0.001), and ≥F3 (0.98 [95% CI: 0.97 to 1.00] versus 0.93 [95% CI: 0.90 to 0.97], P = 0.04). Furthermore, the AUC of TE was comparable with that of APRI in patients with a fibrosis of F4 (0.99 [95% CI: 0.98 to 1.00] versus 0.92 [95% CI: 0.89 to 0.96], P = 0.13). The theoretically obtained adjusted uniform AUC and naturally-observed adjusted AUC for patients with a fibrosis stage of ≥F2 were 1.02 and 0.98, respectively.

Figure 2.

ROC curves of TE (Fibroscan®) and aspartate APRI for the prediction of patients with significant hepatic fibrosis (≥F2), advanced hepatic fibrosis (≥F3), and cirrhosis (F4). (A) AUC of TE (0.96, 95% CI: 0.94 to 0.98) and that of APRI (0.84, 95% CI: 0.79 to 0.88; P < 0.001) for patients with a fibrosis stage of ≥F2. (B) AUC of TE (0.98, 95% CI: 0.97 to 1.00) and that of APRI (0.93, 95% CI: 0.90 to 0.97; P = 0.04) for patients with a fibrosis stage of ≥F3. (C) AUC of TE (0.99, 95% CI: 0.98 to 1.00) and that of APRI (0.92, 95% CI: 0.89 to 0.96; P = 0.13) for patients with a fibrosis stage of F4.

Selected Cut-off Values of LSM and APRI for Patients with Significant Hepatic Fibrosis, Advanced Hepatic Fibrosis, and Cirrhosis

Table 2 shows the selected LSM cut-off values to predict patients with significant hepatic fibrosis, advanced hepatic fibrosis, or cirrhosis. To predict patients with ≥F2, the sensitivity and specificity were 55 and 96% when the LSM was set at 7.1 kPa, and 30 and 100% when the LSM was set at 8.8 kPa; the sensitivity and specificity were 93 and 88% when the optimized LSM was set at 5.3 kPa. To predict patients with ≥F3, the sensitivity and specificity were 45 and 99% when the LSM was set at 9.5 and 9.6 kPa; the sensitivity and specificity were 95 and 99% when the optimized LSM was set at 8.3 kPa. To predict patients with F4, the sensitivity and specificity were 36 and 100% when the LSM was set at 12.5 kPa and 29 and 100% when the LSM was set at 14.6 kPa; the sensitivity and specificity were 100 and 96% when the optimized LSM was set at 9.2 kPa. Furthermore, the sensitivity and specificity of APRI for those with ≥F2, ≥F3, and F4 were 74 and 82%, 93 and 90%, and 100 and 85% when the optimized cut-off values were set at 0.55, 0.75, and 0.80, respectively. Choosing the optimized LSM cut-off values of 5.3, 8.3, and 9.2 kPa, 254 (87%), 281 (97%), and 270 (93%) of the 291 patients (284 patients plus seven patients with failed LSM) with a fibrosis stage of ≥F2, ≥F3, and F4 were correctly diagnosed without PLB, respectively.

Table 2.

Selected cut-off values of LSM and APRI to predict patients with significant hepatic fibrosis (≥F2), advanced hepatic fibrosis (≥F3), and cirrhosis (F4)

| Significant Hepatic Fibrosis (≥F2) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSM (kPa) | Patients Tested, n (%)c |

Actual Fibrosis, n (%)d |

Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | LR + | LR − | DA (%) | |

| All (n = 284) | ≥F2 (n = 101) | <F2 (n = 183) | ||||||||

| 7.1 | 63 (22) | 56 (55) | 7 (4) | 55 | 96 | 89 | 80 | 14.50 | 0.46 | 82 |

| 8.8 | 30 (11) | 30 (30) | 0 (0) | 30 | 100 | 100 | 72 | —e | 0.70 | 75 |

| 5.3a | 116 (41) | 94 (93) | 22 (12) | 93 | 88 | 82 | 96 | 8.11 | 0.08 | 90 |

| APRIb | Patients Tested, n (%) |

Actual Fibrosis, n (%) |

Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | LR + | LR − | DA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 289) | ≥F2 (n = 103) | <F2 (n = 186) | ||||||||

| 0.50 | 137 (47) | 81 (79) | 56 (30) | 79 | 70 | 60 | 86 | 2.66 | 0.30 | 73 |

| 1.50 | 3 (1) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 | 100 | 100 | 65 | —e | 0.97 | 65 |

| 0.55a | 109 (38) | 76 (74) | 33 (18) | 74 | 82 | 69 | 85 | 4.04 | 0.32 | 79 |

| Advanced Hepatic Fibrosis (≥F3) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSM (kPa) | Patients Tested, n (%) |

Actual Fibrosis, n (%) |

Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | LR + | LR − | DA (%) | |

| All (n = 284) | ≥F3 (n = 40) | <F3 (n = 244) | ||||||||

| 9.5 | 20 (7) | 18 (45) | 2 (1) | 45 | 99 | 95 | 92 | 109.80 | 0.55 | 92 |

| 9.6 | 20 (7) | 18 (45) | 2 (1) | 45 | 99 | 95 | 92 | 109.80 | 0.55 | 92 |

| 8.3a | 40 (14) | 38 (95) | 2 (1) | 95 | 99 | 93 | 99 | 77.30 | 0.10 | 99 |

| APRIb | Patients Tested, n (%) |

Actual Fibrosis, n (%) |

Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | LR + | LR − | DA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 289) | ≥F3 (n = 41) | <F3 (n = 248) | ||||||||

| 0.75 | 63 (22) | 38 (93) | 25 (10) | 93 | 90 | 61 | 99 | 9.60 | 0.08 | 90 |

| 1.75 | 3 (1) | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | 2 | 99 | 33 | 86 | 3.02 | 0.98 | 85 |

| 0.75a | 63 (22) | 38 (93) | 25 (10) | 93 | 90 | 61 | 99 | 9.60 | 0.08 | 90 |

| Cirrhosis (F4) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSM (kPa) | Patients Tested, n (%) |

Actual Fibrosis, n (%) |

Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | LR + | LR − | DA (%) | |

| All (n = 284) | =F4 (n = 14) | <F4 (n = 270) | ||||||||

| 12.5 | 5 (2) | 5 (36) | 0 (0) | 36 | 100 | 100 | 97 | —e | 0.64 | 97 |

| 14.6 | 4 (1) | 4 (29) | 0 (0) | 29 | 100 | 100 | 96 | —e | 0.71 | 96 |

| 9.2a | 25 (9) | 14 (100) | 11 (4) | 100 | 96 | 58 | 100 | 27.00 | 0.00 | 96 |

| APRIb | Patients Tested, n (%) |

Actual Fibrosis, n (%) |

Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | LR + | LR − | DA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 289) | =F4 (n = 14) | <F4 (n = 275) | ||||||||

| 1.00 | 28 (10) | 6 (43) | 22 (8) | 43 | 92 | 22 | 97 | 5.61 | 0.62 | 90 |

| 2.00 | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 0 | 99 | 0 | 95 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 94 |

| 0.80a | 58 (20) | 14 (100) | 44 (16) | 100 | 85 | 26 | 100 | 7.05 | 0.00 | 85 |

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; DA, diagnostic accuracy.

The optimized cut-off value was defined as the one with the minimal (1 − sensitivity)2 + (1 − specificity)2 value and the maximal Youden index (sensitivity + specificity − 1).

The total patient number to evaluate APRI was 289 (including 284 patients included in the study and another five patients who received liver biopsy and APRI but who failed LSM).

Patient number and percentage with LSM or APRI levels ≥ the selected cut-off values.

Patient number and percentage with LSM or APRI levels ≥ the selected cut-off values in defined stages of hepatic fibrosis.

Not applicable because the denominator for the likelihood ratio calculation is zero.

Univariate Analysis of Baseline Factors to Predict LSM Accuracy on Optimized Cut-off Values

When the optimized cut-off values of LSM were set at 5.3 and 9.2 kPa, we performed univariate analysis to find baseline factors influencing the LSM accuracy in patients with a fibrosis stage of ≥F2 and F4. The body weight (P = 0.02) was significantly associated with LSM accuracy to predict patients with a fibrosis stage of ≥F2; BMI (P = 0.09), AST level (P = 0.12), ALT level (P = 0.09), and hepatic activity score (P = 0.11) had borderline significance. Furthermore, the hepatic activity score (P = 0.01) was significantly associated with LSM accuracy to predict patients with a fibrosis stage of F4; BMI (P = 0.17) and ALT level (P = 0.16) had borderline significance.

Discussion

The use of simple noninvasive tests to assess the severity of hepatic fibrosis in patients with chronic liver diseases has gained popularity because invasive PLB bears adverse events and interpretation errors. Applying a useful noninvasive tool to replace PLB is even more appealing both for practicing physicians and hemodialysis patients because the platelet dysfunction in hemodialysis patients may potentially cause serious bleeding (19,20). Although prior studies have shown that APRI can be used to evaluate the severity of hepatic fibrosis in hemodialysis patients with CHC, the results clearly indicated that the merit of APRI is to exclude patients with significant hepatic fibrosis, leaving about half of the patients with uncertain severity of hepatic fibrosis (27,28). By comparing the AUCs between TE and APRI, our study showed that the diagnostic performance of TE was better than that of APRI in hemodialysis patients with a fibrosis stage of ≥F2 and ≥F3. Although the AUC of TE was higher than that of APRI to predict patients with cirrhosis, they were not statistically significant, probably because of small cirrhotic patient numbers. These findings are in line with the observations in nonuremic patients with CHC (32).

Although the LSM in hemodialysis patients with fibrosis stages of F0 and F1 showed significant overlap from the box plot, it had excellent power to discriminate those with fibrosis stages of F1 to F4. The AUC of our patients was higher than that of nonuremic patients in predicting a fibrosis stage ≥F2 (0.96 versus 0.79 and 0.83) or ≥F3 (0.98 versus 0.91 and 0.90) and was comparable with these studies in predicting F4 (0.99 versus 0.97 and 0.95) (32,33). Because the variability of AUC is related to the prevalence of different fibrosis stages, the AUCs should be adjusted by the population-based sampling (38). After AUC standardization for different fibrosis stages, the AUC of our patients with a fibrosis stage ≥F2 still reached 0.98 to 1.00. Therefore, the possible distribution bias could be minimized. Although applying the known LSM cut-off values for nonuremic patients with a fibrosis stage of ≥F2 (7.1 and 8.8 kPa), ≥F3 (9.5 and 9.6 kPa), and F4 (12.5 and 14.6 kPa) to predict the severity of hepatic fibrosis in hemodialysis patients had excellent specificity and positive predictive value, these cut-off values could only cover a small portion of patients, which may lessen the clinical usefulness. However, when we adjusted the optimized cut-off values to 5.3, 8.3, and 9.2 kPa, more patients with a fibrosis stage of ≥F2, ≥F3, and F4 who had LSMs greater than the cut-off values could be covered, and the overall diagnostic accuracy was increased. Furthermore, the optimized APRI cut-off values to predict the severity of hepatic fibrosis should also be lowered to improve the diagnostic accuracy (27,28).

Compared with previous studies, the different diagnostic accuracy and optimized cut-off values of LSM in our study may be explained by the following factors: the distribution of fibrosis stages in hemodialysis patients was different from that in nonuremic patients, which may introduce a spectrum bias into the analysis and influence the overall AUCs (38,39); our patients received hemodialysis before LSM to keep adequate dry weight, which might decrease the portal and central venous pressure (40,41); our patients had fasted overnight, which might lessen the increased portal blood flow after food intake and thereby affect LSM (42); and our patients had lower baseline ALT levels and necroinflammatory activity, which may decrease the inaccurate LSM rates (43). However, we believed that the introduction of spectrum bias was the key factor for such differences.

The usefulness of TE to assess the severity of hepatic fibrosis in hemodialysis patients with CHC was demonstrated, with higher diagnostic accuracy and a lower measurement failure rate (2.3%) compared with the general population (31). The lower measurement failure rate was attributed to the lower BMI, younger age, and experienced operators who performed LSMs (34). However, limitations still existed. We assumed that PLB, which takes 1/50,000 the size of the liver, is the gold standard for staging hepatic fibrosis. However, we adopted the strict criteria to ensure adequate sample length, portal tract numbers, and sample interpretation to minimize interpretation errors.

Conclusions

TE is superior to APRI in assessing the severity of hepatic fibrosis in hemodialysis patients with CHC, and applying this simple noninvasive tool can substantially decrease the need of staging PLB.

Disclosures

Jia-Horng Kao received research funding from Vitagenomics; was a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Norvartis, Omrix, and Roche; and was on a speaker's bureau for Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, and Norvartis. Ding-Shinn Chen was a consultant for Norvartis and GlaxoSmithKline. Pei-Jer Chen was a consultant for Norvartis and Roche. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grants from the National Taiwan University Hospital, the National Science Council, and the Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1. Fabrizi F, Poordad FF, Martin P: Hepatitis C infection and the patient with end-stage renal disease. Hepatology 36: 3–10, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berenguer M: Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in hemodialysis patients. Hepatology 48: 1690–1699, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martin P, Fabrizi F: Hepatitis C virus and kidney disease. J Hepatol 49: 613–624, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu CH, Kao JH: Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 26: 228–239, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu CH, Liang CC, Liu CJ, Lin JW, Chen SI, Hung PH, Tsai HB, Lai MY, Chen PJ, Chen DS, Kao JH: Pegylated interferon alpha-2a monotherapy for hemodialysis patients with acute hepatitis C. Clin Infect Dis 51: 541–549, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nakayama E, Akiba T, Marumo F, Sato C: Prognosis of anti-hepatitis C virus antibody-positive patients on regular hemodialysis therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1896–1902, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fabrizi F, Martin P, Dixit V, Bunnapradist S, Dulai G: Meta-analysis: Effect of hepatitis C virus infection on mortality in dialysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 20: 1271–1277, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mathurin P, Mouquet C, Poynard T, Sylla C, Benalia H, Fretz C, Thibault V, Cadranel JF, Bernard B, Opolon P, Coriat P, Bitker MO: Impact of hepatitis B and C virus on kidney transplantation outcome. Hepatology 29: 257–263, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fabrizi F, Dixit V, Messa P, Martin P: Interferon monotherapy of chronic hepatitis C in dialysis patients: Meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Viral Hepat 15: 79–88, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gordon CE, Uhlig K, Lau J, Schmid CH, Levey AS, Wong JB: Interferon treatment in hemodialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of treatment efficacy and harms. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 263–277, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu CH, Liang CC, Lin JW, Chen SI, Tsai HB, Chang CS, Hung PH, Kao JH, Liu CJ, Lai MY, Chen JH, Chen PJ, Kao JH, Chen DS: Pegylated interferon alpha-2a versus standard interferon alpha-2a for treatment-naive dialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C: A randomised study. Gut 57: 525–530, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu CH, Liang CC, Liu CJ, Tsai HB, Hung PH, Hsu SJ, Chen SI, Lin JW, Lai MY, Chen JH, Chen PJ, Chen DS, Kao JH: Pegylated interferon alpha-2a plus low-dose ribavirin for the retreatment of dialysis chronic hepatitis C patients who relapsed from prior interferon monotherapy. Gut 58: 314–316, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Castéra L, Pinzani M: Non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis: Are we ready? Lancet 375: 1419–1420, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bravo AA, Sheth SG, Chopra S: Liver biopsy. N Engl J Med 344: 495–500, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, Nelson RC, Smith AD. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases: Liver biopsy. Hepatology 49: 1017–1044, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ozdoğan M, Ozgür O, Boyacioğlu S, Coçskun M, Kart H, Ozdal S, Telatar H: Percutaneous liver biopsy complications in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephron 74: 442–443, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cotler SJ, Diaz G, Gundlapalli S, Jakate S, Chawla A, Mital D, Jensik S, Jensen DM: Characteristics of hepatitis C in renal transplant candidates. J Clin Gastroenterol 35: 191–195, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pawa S, Ehrinpreis M, Mutchnick M, Janisse J, Dhar R, Siddiqui FA: Percutaneous liver biopsy is safe in chronic hepatitis C patients with end-stage renal disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 5: 1316–1320, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gangji AS, Sohal AS, Treleaven D, Crowther MA: Bleeding in patients with renal insufficiency: A practical guide to clinical management. Thromb Res 118: 423–428, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kaw D, Malhotra D: Platelet dysfunction and end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial 19: 317–322, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maharaj B, Maharaj RJ, Leary WP, Cooppan RM, Naran AD, Pirie D, Pudifin DJ: Sampling variability and its influence on the diagnostic yield of percutaneous needle biopsy of the liver. Lancet 1: 523–525, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bedossa P, Dargere D, Paradis V: Sampling variability of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 38: 1449–1457, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS: A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 38: 518–526, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu CH, Lin JW, Tsai FC, Yang PM, Lai MY, Chen JH, Kao JH, Chen DS: Noninvasive tests for the prediction of significant hepatic fibrosis in hepatitis C virus carriers with persistently normal alanine aminotransferases. Liver Int 26: 1087–1094, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shaheen AA, Myers RP: Diagnostic accuracy of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the prediction of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: A systematic review. Hepatology 46: 912–921, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boyacioğlu S, Gür G, Yilmaz U, Korkmaz M, Demirhan B, Bilezikçi B, Ozdemir N: Investigation of possible clinical and laboratory predictors of liver fibrosis in hemodialysis patients infected with hepatitis C virus. Transplant Proc 36: 50–52, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schiavon LL, Schiavon JL, Filho RJ, Sampaio JP, Lanzoni VP, Silva AE, Ferraz ML: Simple blood tests as noninvasive markers of liver fibrosis in hemodialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 46: 307–314, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu CH, Liang CC, Liu CJ, Hsu SJ, Lin JW, Chen SI, Hung PH, Tsai HB, Lai MY, Chen PJ, Chen JH, Chen DS, Kao JH: The ratio of aminotransferase to platelets is a useful index for predicting hepatic fibrosis in hemodialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C. Kidney Int 78: 103–109, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Talwalkar JA, Kurtz DM, Schoenleber SJ, West CP, Montori VM: Ultrasound-based transient elastography for the detection of hepatic fibrosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 5: 1214–1220, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Friedrich-Rust M, Ong MF, Martens S, Sarrazin C, Bojunga J, Zeuzem S, Herrmann E: Performance of transient elastography for the staging of liver fibrosis: A meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 134: 960–974, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Castéra L, Forns X, Alberti A: Non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis using transient elastography. J Hepatol 48: 835–847, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Castéra L, Vergniol J, Foucher J, Le Bail B, Chanteloup E, Haaser M, Darriet M, Couzigou P, De Lédinghen V: Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 128: 343–350, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ziol M, Handra-Luca A, Kettaneh A, Christidis C, Mal F, Kazemi F, de Lédinghen V, Marcellin P, Dhumeaux D, Trinchet JC, Beaugrand M: Noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis by measurement of stiffness in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 41: 48–54, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Castéra L, Foucher J, Bernard PH, Carvalho F, Allaix D, Merrouche W, Couzigou P, de Lédinghen V: Pitfalls of liver stiffness measurement: A 5-year prospective study of 13,369 examinations. Hepatology 51: 828–835, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bedossa P, Poynard T: An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. The METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Hepatology 24: 289–293, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hanley JA, McNeil BJ: A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology 148: 839–843, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sanyal AJ. American Gastroenterological Association: AGA technical review on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 123: 1705–1725, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Poynard T, Halfon P, Castera L, Munteanu M, Imbert-Bismut F, Ratziu V, Benhamou Y, Bourlière M, de Ledinghen V. FibroPaca Group: Standardization of ROC curve areas for diagnostic evaluation of liver fibrosis markers based on prevalences of fibrosis stages. Clin Chem 53: 1615–1622, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fraquelli M, Rigamonti C, Casazza G, Conte D, Donato MF, Ronchi G, Colombo M: Reproducibility of transient elastography in the evaluation of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut 56: 968–973, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Millonig G, Friedrich S, Adolf S, Fonouni H, Golriz M, Mehrabi A, Stiefel P, Pöschl G, Büchler MW, Seitz HK, Mueller S: Liver stiffness is directly influenced by central venous pressure. J Hepatol 52: 206–210, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Khurana S, Simcox T, Twaddell W, Drachenberg C, Flasar M: Dialysis reduces portal pressure in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Artif Organs 34: 570–579, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mederacke I, Wursthorn K, Kirschner J, Rifai K, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H, Bahr MJ: Food intake increases liver stiffness in patients with chronic or resolved hepatitis C virus infection. Liver Int 29: 1500–1506, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Coco B, Oliveri F, Maina AM, Ciccorossi P, Sacco R, Colombatto P, Bonino F, Brunetto MR: Transient elastography: A new surrogate marker of liver fibrosis influenced by major changes of transaminases. J Viral Hepat 14: 360–369, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]