Abstract

Summary

Background and objectives

Dialysis patients show “reverse causality” between serum cholesterol and mortality. No previous studies clearly separated the risk of incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) and the risk of death or fatality after such events. We tested a hypothesis that dyslipidemia increases the risk of incident atherosclerotic CVD and that protein energy wasting (PEW) increases the risk of fatality after CVD events in hemodialysis patients.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This was an observational cohort study in 45,390 hemodialysis patients without previous history of myocardial infarction (MI), cerebral infarction (CI), or cerebral bleeding (CB) at the end of 2003, extracted from a nationwide dialysis registry in Japan. Outcome measures were new onsets of MI, CI, CB, and death in 1 year.

Results

The incidence rates of MI, CI, and CB were 1.43, 2.53, and 1.01 per 100 person-years, and death rates after these events were 0.23, 0.21, and 0.29 per 100 person-years, respectively. By multivariate logistic regression analysis, incident MI was positively associated with non-HDL cholesterol (non–HDL-C) and inversely with HDL cholesterol (HDL-C). Incident CI was positively associated with non–HDL-C, whereas CB was not significantly associated with these lipid parameters. Among the patients who had new MI, CI, and/or CB, death risk was not associated with HDL-C or non–HDL-C, but with higher age, lower body mass index, and higher C-reactive protein levels.

Conclusions

In this hemodialysis cohort, dyslipidemia was associated with increased risk of incident atherosclerotic CVD, and protein energy wasting/inflammation with increased risk of death after CVD events.

Introduction

In the general population, dyslipidemia is one of the established risk factors for coronary heart disease (1,2), and a high body mass index (BMI) is associated with increased cardiovascular risk and mortality (3). However, the opposite association has been reported between mortality and these risk factors in many populations,including the elderly people (4,5), hospitalized patients (6), patients with chronic heart failure (7), cancer (8), and advanced stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD) (9–12). Such unexpected results in epidemiology are called “risk factor paradox” (13,14), “reverse causality,” or “reverse epidemiology” (7).

In dialysis populations, it has been assumed that malnutrition and inflammation promote atherosclerosis (15), based on the coexistence of malnutrition, inflammation, and atherosclerotic disease (MIA syndrome) (15). An expert panel (16) recently recommended the term “protein energy wasting” (PEW) rather than “malnutrition” for loss of body protein mass and fuel reserves. The presence of PEW and/or inflammation may explain the paradoxical association between total cholesterol (TC) and mortality risk in dialysis patients, because TC levels are decreased in such conditions (17). However, there is a large cohort study (18) against the MIA hypothesis showing that dialysis patients with a lower BMI had a lower hazard of hospitalized acute coronary syndrome. Importantly, the MIA hypothesis was based on cardiovascular mortality, whereas the latter cohort study took incident cardiac events as an outcome. Theoretically, the risk of death from cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the product of the risk of an incident CVD event and the risk of death (fatality) after such an event. Fatality rate after incident CVD among CKD patients is substantially higher than those with normal renal function (19–22). Thus, the difference in outcome measures may explain the apparent discrepancy between studies and also the reverse epidemiology.

We previously hypothesized that dyslipidemia is a factor promoting atherosclerosis and incident CVD and that PEW is a factor associated with increased fatality after CVD events (13,14). This notion is indirectly supported by positive associations of atherosclerotic vascular changes with non-HDL cholesterol (non–HDL-C) in patients with advanced stages of CKD (23–28). Thus far, however, no direct information is available that shows the relationship between serum lipids and incident CVD in dialysis populations. In addition, it is poorly understood what factors are contributing to increased fatality after CVD events in dialysis patients.

The primary aim of this study was to examine the risk factors for incident CVD and those for fatality after such events. The secondary aim was to compare the powers of lipid parameters including TC, HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), and non–HDL-C levels in predicting incident CVD.

Subjects and Methods

Registry of Dialysis Patients

The Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy (JSDT) has been conducting annual questionnaire surveys of dialysis facilities throughout Japan since 1968, compiling a computer-based registry since 1983. The Committee of Renal Data Registry (JSDT-CRDR) is conducting statistics and investigation. The questionnaire for the year-end survey comprises four pages, and the response rate for the first page has been nearly 100% every year (29). The questionnaires were filled out by the staff of each facility and sent back to the office of the JSDT-CRDR to build a database. In addition to the routine questionnaire, some items of interest are included for the new survey each year. Several studies (29,30) based on these surveys were published. Details on the inception, limitations, validity, variables, and questionnaires used in the study are available online at the JSDT website (www.jsdt.or.jp). As the new survey items in 2003, the questionnaire included serum TC, triglycerides (TG), and HDL-C levels. Also, the questions regarding history of myocardial infarction (MI), cerebral infarction (CI), or cerebral bleeding (CB) were included in the surveys at the ends of 2003 and 2004, so that new onsets of these vascular events can be detected.

Data Extraction

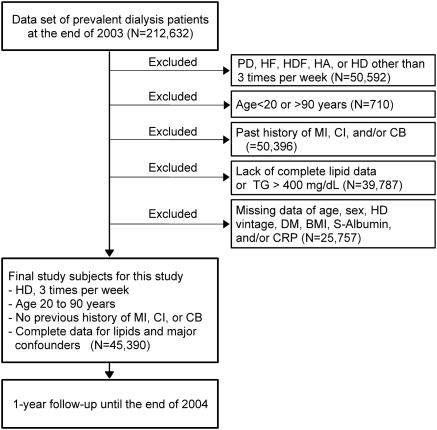

A standard analysis file (SAF) was prepared for this study (JRDR-09108). Figure 1 shows the data extraction process. The SAF contained a total of 212,632 dialysis patients at the end of 2003 whose survival status at the end of 2004 was available. We excluded patients treated with peritoneal dialysis, hemofiltration, hemodiafiltration, hemodialysis with hemoadsorption, and hemodialysis other than thrice weekly treatment. We also excluded those who were younger than 20 years of age or older than 90 years of age. We further excluded patients with a history of MI, CI, and/or CB, those lacking data of lipids, age, gender, dialysis vintage, diabetes mellitus (diabetic nephropathy as the cause of end-stage kidney disease), BMI, serum albumin, and/or C-reactive protein (CRP). The final subjects for this study were 45,390 patients treated with thrice weekly hemodialysis without a history of MI, CI, or CB, between 20 and 90 years of age at the end of 2003, and whose serum lipids and the seven relevant factors were all available.

Figure 1.

Chart of subject selection for this study. From the total subjects in the data set (n = 212,632), we selected patients treated with hemodialysis three times per week whose age was between 20 and 90 years old without previous history of MI, CI, or CB. Patients were excluded when relevant data were not available. The 45,390 subjects were followed-up for 1 year in the database. PD, peritoneal dialysis; HF, hemofiltration; HDF, hemodiafiltration; HA, hemodialysis with hemoadsorption; HD, hemodialysis; DM, diabetes mellitus; S-albumin, serum albumin.

Serum Lipids

Patients were not asked to fast for blood tests, and 94.4% of the subjects were 0 to 6 hours postprandial. Non–HDL-C was calculated by subtracting HDL-C from TC. LDL-C was calculated by the Friedewald formula. For this reason, patients with TG > 400 mg/dl were excluded. Among the 162,149 patients whose TG levels were available in the SAF, only 1380 (0.9%) had TG > 400 mg/dl.

Statistics

We summarized categorical data as percentages and continuous variables as medians (25th and 75th percentile levels). Correlation between variables was evaluated by Spearman's rank correlation test. Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) were calculated by logistic regression analysis, and adjustment was performed using multivariate models. P < 0.05 was considered significant. All these calculations were performed using statistic software JMP version 8.0.1 (SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan) installed in a Windows personal computer.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of the Cohort

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the cohort. Among the total cohort, 59.1% were men, and 25.5% had diabetic nephropathy. The median levels were 62 years for age, 66 months for duration of hemodialysis, 20.6 kg/m2 for BMI, 3.9 g/dl for serum albumin, and 0.1 mg/dl for CRP. Median levels of TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, and non–HDL-C were 157, 96, 45, 88, and 109 mg/dl, respectively. The prevalence of increased TG >150 and >200 mg/dl was 20.0 and 8.6%, respectively. LDL-C levels >100 and >120 mg/dl were found in 34.2 and 15.5% of the total subjects, respectively. Non–HDL-C levels >130 and >150 mg/dl were seen in 28.3 and 14.0%, respectively. Decreased HDL-C levels <40 mg/dl were found in 35.6%.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the hemodialysis cohort

| Total number of subjects | 45,390 |

| Age (years) | 62 (53 to 71) |

| Gender (men %) | 59.1 |

| Dialysis vintage (months) | 66 (30 to 130) |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 25.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.6 (18.8 to 22.8) |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 3.9 (3.6 to 4.1) |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 0.1 (0 to 0.4) |

| TC (mg/dl) | 157 (134 to 182) |

| TG (mg/dl) | 96 (67 to 137) |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 45 (36 to 55) |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 88 (69 to 109) |

| Non–HDL-C (mg/dl) | 109 (88 to 133) |

The table gives number, percentage, and median (25th to 75th percentile) levels.

Table 2 shows correlations between five markers of serum lipids and three markers of PEW and inflammation at baseline. BMI positively correlated with TC, TG, LDL-C, and non–HDL-C but inversely with HDL-C. Serum albumin positively correlated with all of the five lipid variables, particularly with HDL-C. CRP inversely correlated with TC and HDL-C but positively correlated with TG and non–HDL-C. CRP was not significantly correlated with LDL-C.

Table 2.

Correlation between serum lipid and markers of protein-energy wasting and inflammation at baseline

| BMI | Serum Albumin | CRP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TC | 0.032a | 0.112a | −0.047a |

| TG | 0.248a | 0.071a | 0.065a |

| HDL-C | −0.275a | 0.137a | −0.170a |

| LDL-C | 0.046a | 0.024a | −0.0005 (NS) |

| Non–HDL-C | 0.132a | 0.051a | 0.024a |

The table shows Spearman's rank correlation coefficients. NS, not significant.

P < 0.005.

Clinical Outcomes

Of the 45,390 subjects, 2313 patients died, whereas 43,077 patients were alive after the 1-year follow-up. The size of total observation was 44,190 person-years. We identified 632 cases (1.43 per 100 person-years) with incident MI, among whom 100 cases (0.23 per 100 person-years) died after MI. We identified 1119 (2.53 per 100 person-years) cases with incident CI, among whom 92 cases (0.21 person-years) died after CI. Incident CB was identified in 473 cases (1.01 per 100 person-years), among whom 130 cases (0.29 per 100 person-years) died after CB.

Univariate Predictors of the Clinical Outcomes

Table 3 shows the results of unadjusted logistic regression analysis of predictors of incident MI, incident CI, incident CB, and all-cause mortality.

Table 3.

Univariate associations of lipid and nonlipid factors with the four clinical outcomes

| Incident MI | Incident CI | Incident CB | All-Cause Death | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 1 year) | 1.03 (1.02 to 1.04)a | 1.05 (1.04 to 1.05)a | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02)c | 1.07 (1.06 to 1.07)a |

| Male (versus female) | 1.67 (1.41 to 1.99)a | 1.19 (1.06 to 1.35)a | 1.15 (0.96 to 1.39) | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.18) |

| DM (versus non-DM) | 2.01 (1.71 to 2.36)a | 1.98 (1.75 to 2.24)a | 1.28 (1.04 to 1.55)c | 1.58 (0.99 to 1.18)a |

| HD duration (per 1 year) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99)b | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98)a | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.00) | 0.87 (0.85 to 0.88)a |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.05)c | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.99)a | 0.97 (0.94 to 1.00) | 0.87 (0.85 to 0.88)a |

| Albumin (per 1 g/dl) | 0.51 (0.42 to 0.62)a | 0.38 (0.33 to 0.45)a | 0.69 (0.54 to 0.87)b | 0.16 (0.15 to 0.018)a |

| CRP (per 1 mg/dl) | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.09)b | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.10)a | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.09)c | 1.23 (1.21 to 1.26)a |

| TC | ||||

| Q1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Q2 | 0.91 (0.72 to 1.14) | 0.87 (0.73 to 1.03) | 0.87 (0.67 to 1.11) | 0.73 (0.65 to 0.81)a |

| Q3 | 1.05 (0.84 to 1.30) | 0.93 (0.79 to 1.10) | 0.81 (0.63 to 1.05) | 0.60 (0.54 to 0.68)a |

| Q4 | 1.03 (0.83 to 1.29) | 0.92 (0.77 to 1.08) | 0.86 (0.66 to 1.10) | 0.55 (0.49 to 0.62)a |

| TG | ||||

| Q1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Q2 | 1.00 (0.79 to 1.26) | 1.10 (0.93 to 1.30) | 0.87 (0.68 to 1.11) | 0.95 (0.85 to 1.06) |

| Q3 | 1.22 (0.97 to 1.53) | 0.98 (0.82 to 1.17) | 0.72 (0.56 to 0.93)c | 0.79 (0.70 to 0.89)a |

| Q4 | 1.25 (1.00 to 1.57)c | 1.09 (0.92 to 1.29) | 0.71 (0.55 to 0.92)c | 0.66 (0.59 to 0.75)a |

| HDL-C | ||||

| Q1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Q2 | 0.80 (0.65 to 0.97)c | 0.87 (0.74 to 1.02) | 1.03 (0.79 to 1.35) | 0.70 (0.62 to 0.78)a |

| Q3 | 0.60 (0.48 to 0.75)a | 0.79 (0.67 to 0.93)b | 1.11 (0.85 to 1.45) | 0.71 (0.64 to 0.80)a |

| Q4 | 0.43 (0.34 to 0.54)a | 0.63 (0.53 to 0.75)a | 1.12 (0.86 to 1.44) | 0.54 (0.48 to 0.61)a |

| LDL-C | ||||

| Q1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Q2 | 1.05 (0.83 to 1.34) | 0.96 (0.80 to 1.13) | 0.93 (0.73 to 1.19) | 0.96 (0.86 to 1.07) |

| Q3 | 1.31 (1.04 to 1.64)c | 1.05 (0.89 to 1.24) | 0.70 (0.54 to 0.91)b | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.95)b |

| Q4 | 1.43 (1.14 to 1.79)b | 1.10 (0.93 to 1.30) | 0.88 (0.68 to 1.13) | 0.78 (0.70 to 0.88)a |

| Non–HDL-C | ||||

| Q1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Q2 | 1.15 (0.90 to 1.46) | 0.90 (0.75 to 1.07) | 0.97 (0.76 to 1.24) | 0.92 (0.82 to 1.02) |

| Q3 | 1.29 (1.02 to 1.63)c | 1.07 (0.90 to 1.26) | 0.75 (0.58 to 0.98)c | 0.74 (0.66 to 0.83)a |

| Q4 | 1.53 (1.22 to 1.92)a | 1.11 (0.94 to 1.31) | 0.85 (0.66 to 1.09) | 0.71 (0.63 to 0.80)a |

The table gives odds ratios (95% confidence intervals). DM, diabetes mellitus, HD, hemodialysis; Q1 to Q4, lowest to highest quartile.

P < 0.001,

P < 0.01, and

P < 0.05.

Incident MI was associated with higher age, male gender, diabetes mellitus, short duration of HD, higher BMI, lower serum albumin, and higher CRP levels. Higher TG, lower HDL-C, higher LDL-C, and higher non–HDL-C levels were significant univariate predictors for incident MI, whereas TC was not.

Incident CI was associated with higher age, male gender, diabetes mellitus, shorter duration of HD, lower BMI, lower serum albumin, and higher CRP levels. Lower HDL-C was a significant univaritate predictor of incident CI, whereas TC, TG, LDL-C, and non–HDL-C were not.

Incident CB was associated with higher age, diabetes mellitus, lower serum albumin, and higher CRP. Lower risk of incident CB was associated with higher quartiles (Q3 and Q4) of TG, Q3 of LDL-C, and Q3 of non–HDL-C.

All-cause mortality was associated with higher age, diabetes mellitus, shorter duration of HD, lower BMI, lower serum albumin, and higher CRP levels. Higher TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, and non–HDL-C levels were all significant univariate predictors of lower risk for all-cause mortality.

Adjusted Association of Serum Lipids with Clinical Outcomes

Table 4 shows the association between serum lipids and clinical outcomes by logistic regression analysis adjusted for seven nonlipid variables including age, gender, duration of dialysis, diabetes mellitus, BMI, serum albumin, and CRP.

Table 4.

Adjusted odds ratios for incident MI, CI, and CB and all-cause mortality according to quartiles of lipid measurements

| Lipid Variables | Quartile | Incident MI | Incident CI | Incident CB | All-Cause Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC | Q1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Q2 | 1.05 (0.83 to 1.32) | 1.00 (0.84 to 1.19) | 0.92 (0.71 to 1.18) | 0.93 (0.83 to 1.05) | |

| Q3 | 1.32 (1.06 to 1.66)c | 1.14 (0.96 to 1.36) | 0.89 (0.68 to 1.16) | 0.86 (0.75 to 0.98)c | |

| Q4 | 1.45 (1.15 to 1.83)b | 1.20 (1.01 to 1.44)c | 0.96 (0.74 to 1.25) | 0.86 (0.75 to 0.98)c | |

| TG | Q1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Q2 | 1.04 (0.82 to 1.32) | 1.13 (0.95 to 1.34) | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.13) | 1.02 (0.91 to 1.15) | |

| Q3 | 1.30 (1.03 to 1.64)c | 1.07 (0.89 to 1.28) | 0.75 (0.58 to 0.97)c | 0.97 (0.85 to 1.10) | |

| Q4 | 1.36 (1.08 to 1.72)b | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.55)b | 0.76 (0.58 to 0.99)c | 1.03 (0.91 to 1.18) | |

| HDL-C | Q1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Q2 | 0.89 (0.73 to 1.09) | 0.94 (0.80 to 1.10) | 1.07 (0.82 to 1.39) | 0.76 (0.68 to 0.86)a | |

| Q3 | 0.74 (0.59 to 0.93)b | 0.91 (0.77 to 1.09) | 1.18 (0.90 to 1.55) | 0.84 (0.74 to 0.95)b | |

| Q4 | 0.61 (0.47 to 0.78)a | 0.83 (0.70 to 1.00)c | 1.23 (0.94 to 1.62) | 0.73 (0.64 to 0.83)a | |

| LDL-C | Q1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Q2 | 1.09 (0.86 to 1.38) | 0.97 (0.81 to 1.15) | 0.94 (0.74 to 1.21) | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.14) | |

| Q3 | 1.43 (1.13 to 1.80)b | 1.08 (0.91 to 1.29) | 0.73 (0.56 to 0.95)c | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.08) | |

| Q4 | 1.68 (1.33 to 2.11)a | 1.19 (1.00 to 1.42)c | 0.93 (0.72 to 1.20) | 0.96 (0.84 to 1.09) | |

| Non-HDL-C | Q1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Q2 | 1.21 (0.95 to 1.55) | 0.94 (0.78 to 1.12) | 1.00 (0.78 to 1.28) | 1.02 (0.91 to 1.15) | |

| Q3 | 1.43 (1.13 to 1.82)b | 1.16 (0.97 to 1.37) | 0.88 (0.61 to 1.03) | 0.91 (0.80 to 1.03) | |

| Q4 | 1.83 (1.44 to 2.31)a | 1.28 (1.08 to 1.53)b | 0.92 (0.71 to 1.19) | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.13) |

The table gives odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for each quartiles (Q1 to Q4) of lipid variables adjusted for age, gender, dialysis vintage, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, serum albumin, and C-reactive protein levels. Q1 to Q4, lowest to highest quartile.

P < 0.001,

P < 0.01, and

P < 0.05.

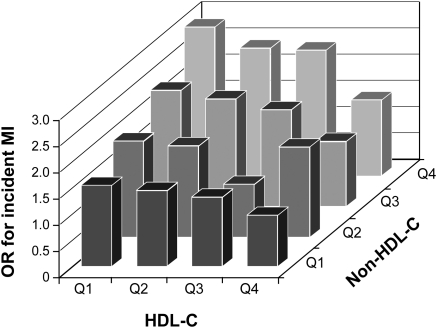

Incident MI was associated with higher TC, TG, LDL-C, and non–HDL-C levels, and lower HDL-C in the multivariate adjusted model. The odds ratio of MI was higher for non–HDL-C than for LDL-C. Figure 2 shows the odds ratios of incident MI for the 4 × 4 categories of HDL-C and non–HDL-C. When the subjects in the highest quartile of HDL-C and the lowest quartile of non–HDL-C were taken as reference, those in the lowest quartile of HDL-C and the highest quartile of non–HDL-C had an odds ratio of 2.91 (1.86 to 4.71) for incident MI.

Figure 2.

Adjusted odds ratios for incident MI according to HDL-C and non–HDL-C quartiles. Bars represent odds ratios for incident MI in 16 subgroups of the subjects adjusted for age, gender, dialysis vintage, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, serum albumin, and C-reactive protein levels. The subgroup in the highest quartile of HDL-C (Q4) and the lowest quartile of non–HDL-C (Q1) was the referent. The odds ratio of the lowest HDL-C (Q1) and the highest non–HDL-C (Q4) was 2.91 (1.86 to 4.71), P < 0.0001. OR, odds ratio.

Incident CI was associated with higher levels of TC, TG, LDL-C, and non–HDL-C, and lower level of HDL-C in the multivariate adjusted model. The odds ratio of non–HDL-C was higher than that of LDL-C, although these associations of lipid parameters with CI were less impressive than their associations with MI.

Incident CB was not significantly associated with TC, HDL-C, or non–HDL-C. Risk of CB showed an inverse association with TG and a U-shaped relationship with LDL-C with the lowest risk in Q3.

Risk of all-cause mortality was again inversely associated with TC and HDL-C but not with TG, LDL-C, or non–HDL-C in the multivariate adjusted model, suggesting that the inverse association between TC and the risk of all-cause death was caused by an increased death risk associated with a low HDL-C.

Adjusted Associations of Markers for PEW and Inflammation with Clinical Outcomes

Table 5 summarizes the results of multivariate logistic regression analyses of predictors of clinical outcomes. In these analyses, we intended to look at the impacts of nonlipid variables, particularly of BMI, serum albumin, and CRP, when simultaneously adjusted for both HDL-C and non–HDL-C levels as the lipid variables. In such models, incident MI was associated with higher BMI, lower serum albumin, and higher CRP levels. Incident CI was associated with lower BMI, lower serum albumin, and higher CRP levels. Incident CB was associated with lower serum albumin and higher CRP levels. All-cause mortality was associated with lower BMI, lower serum albumin, and higher CRP levels.

Table 5.

Independent association of markers of protein-energy wasting and inflammation with clinical outcomes.

| Incident MI | Incident CI | Incident CB | All-Cause Mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.03a | 1.04a | 1.01 | 1.05a |

| (per 1 year) | (1.02 to 1.04) | (1.04 to 1.05) | (1.00 to 1.01) | (1.05 to 1.06) |

| Male | 1.80a | 1.34a | 1.20 | 1.26a |

| (versus female) | (1.50 to 2.16) | (1.18 to 1.53) | (0.98 to 1.46) | (1.14 to 1.38) |

| DM | 1.77a | 1.84a | 1.26c | 1.58a |

| (versus non-DM) | (1.49 to 2.11) | (1.61 to 2.10) | (1.01 to 1.55) | (1.43 to 1.74) |

| HD vintage | 1.01a | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01c |

| (per 1 year) | (1.00 to 1.02) | (0.99 to 1.01) | (0.98 to 1.01) | (1.00 to 1.02) |

| BMI | 1.01 | 0.97b | 0.98 | 0.89a |

| (per 1 kg/m2) | (0.98 to 1.03) | (0.95 to 0.99) | (0.94 to 1.01) | (0.87 to 0.90) |

| Albumin | 0.66a | 0.56a | 0.74c | 0.30a |

| (per 1 g/dl) | (0.53 to 0.82) | (0.47 to 0.65) | (0.58 to 0.95) | (0.27 to 0.33) |

| CRP | 1.03a | 1.04b | 1.04 | 1.13a |

| (per 1 mg/dl) | (0.98 to 1.07) | (1.01 to 1.07) | (0.99 to 1.08) | (1.12 to 1.16) |

| HDL-C | 0.64a | 0.90 | 1.29c | 0.72a |

| (per 38.7 mg/dl) | (0.50 to 0.81) | (0.76 to 1.07) | (1.02 to 1.61) | (0.64 to 0.82) |

| Non–HDL-C | 1.24a | 1.11b | 0.95 | 0.99 |

| (per 38.7 mg/dl) | (1.14 to 1.35) | (1.04 to 1.19) | (0.85 to 1.05) | (0.94 to 1.04) |

The table gives odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) by multivariate logistic regression analyses. DM, diabetes mellitus; HD, hemodialysis.

P < 0.001,

P < 0.01, and

P < 0.05.

Predictors of Death after CVD Events

Among the patients who experienced incident MI, CI, and/or CB during the follow-up, some patients died, whereas others survived at the end of the follow-up. We examined factors associated with death after such events (Table 6). The significant predictors of death after MI were higher age and lower serum albumin. The significant predictors of death after CI were higher age, longer duration of dialysis, lower BMI, lower serum albumin, and higher CRP levels. The significant predictors of death after CB were lower BMI and higher CRP levels. When the three types of CVD were combined, the predictors of death after the combined CVD events were higher age, lower BMI, and higher CRP levels. Lipid parameters did not predict death after incident CVD.

Table 6.

Factors associated with death after vascular events

| Death after MI | Death after CI | Death after CB | Death after MI, CI, or CB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate logistic regression | ||||

| age (per 1 year) | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.06)a | 1.05 (1.03 to 1.08)a | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.03) |

| male (versus female) | 0.67 (0.43 to 1.05) | 0.59 (0.38 to 0.90)c | 1.14 (0.75 to 1.75) | 0.79 (0.62 to 1.01) |

| DM (versus non-DM) | 1.01 (0.65 to 1.55) | 0.95 (0.61 to 1.47) | 1.01 (0.65 to 1.57) | 0.91 (0.71 to 1.17) |

| HD vintage (per 1 year) | 1.00 (0.97 to 1.04) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.07)c | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.05) | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.04)c |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | 0.93 (0.87 to 1.00)c | 0.85 (0.79 to 0.92)a | 0.91 (0.85 to 0.97)b | 0.91 (0.87 to 0.94)a |

| albumin (per 1 g/dl) | 0.33 (0.19 to 0.59)a | 0.37 (0.22 to 0.64)a | 1.27 (0.77 to 2.11) | 0.65 (0.48 to 0.88)b |

| CRP (per 1 mg/dl) | 1.15 (1.03 to 1.30)c | 1.13 (1.03 to 1.23)c | 1.14 (1.01 to 1.29)c | 1.12 (1.06 to 1.19)a |

| HDL-C (per 38.7 mg/dl) | 1.30 (0.74 to 2.23) | 0.98 (0.55 to 1.69) | 1.09 (0.66 to 1.78) | 1.22 (0.90 to 1.64) |

| non–HDL-C (per 38.7 mg/dl) | 0.37 (0.08 to 1.66) | 1.03 (0.81 to 1.30) | 0.83 (0.66 to 1.05) | 0.88 (0.77 to 1.01) |

| Multivariate logistic regression | ||||

| age (per 1 year) | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.06)b | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.08)a | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.03)c |

| male (versus female) | 0.74 (0.46 to 1.21) | 0.79 (0.49 to 1.27) | 1.14 (0.72 to 1.84) | 0.85 (0.65 to 1.11) |

| DM (versus non-DM) | 1.21 (0.74 to 1.98) | 1.59 (0.96 to 2.63) | 1.10 (0.67 to 1.79) | 1.10 (0.83 to 1.44) |

| HD vintage (per 1 year) | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.05) | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.09)b | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.04) | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.04) |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.06) | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.98)a | 0.89 (0.83 to 0.96)b | 0.93 (0.89 to 0.97)a |

| albumin (per 1 g/dl) | 0.47 (0.25 to 0.87)c | 0.55 (0.31 to 0.98)c | 1.64 (0.95 to 2.87) | 0.84 (0.60 to 1.16) |

| CRP (per 1 mg/dl) | 1.11 (0.98 to 1.26) | 1.12 (1.02 to 1.23)c | 1.17 (1.03 to 1.35)c | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.18)a |

| HDL-C (per 38.7 mg/dl) | 1.38 (0.75 to 2.47) | 0.96 (0.51 to 1.74) | 0.87 (0.49 to 1.52) | 1.10 (0.79 to 1.53) |

| non–HDL-C (per 38.7 mg/dl) | 0.87 (0.76 to 2.48) | 1.10 (0.85 to 1.42) | 0.86 (0.67 to 1.10) | 0.92 (0.79 to 1.53) |

Among the subjects with incident MI (n = 632), incident CI (n = 1119), incident CB (n = 473), and any of the three (n = 2098), we examined the factors associated with death after these vascular events by univariate and multivariate logistic regression models including the nine factors in the table. The table gives odds ratios (95% confidence intervals). DM, diabetes mellitus; HD, hemodialysis.

P < 0.001,

P < 0.01, and

P < 0.05.

Discussion

The relative risk of death from CVD was reported to be between 10 and 30 in hemodialysis patients compared with the general population in the United States (31) and Japan (32). Hemodialysis patients have several times higher risk of incident MI (21) and stroke (20), but the increased incidence of such events cannot fully explain the extremely elevated risk for death from CVD. The discrepancy between incidence of CVD and mortality rate from CVD indirectly suggests the increased risk of fatality after these vascular events in dialysis patients (13,14,33). In fact, the fatality rate is significantly higher in dialysis patients after acute MI (19,21) and stroke (20). Risk factors for incident CVD and those for fatality after CVD event are probably different, and if so, it may explain the reverse epidemiology in dialysis patients. In this context, this study has made the following two novel findings.

First, our study clearly showed that the lipid risk factors for incident MI in this cohort of hemodialysis patients were very similar to those in the general population. In multivariate logistic regression models, the risk of incident MI was positively associated with high levels of TC, TG, LDL-C, and non–HDL-C and inversely associated with HDL-C. Compared with the risk of MI, the risk of incident CI was less impressively associated with these lipid variables. These results were consistent with the epidemiology in the general population, indicating that dyslipidemia is an important risk factor for atherosclerotic CVD, particularly for coronary heart disease, even in hemodialysis patients.

Second, this study showed that markers of PEW and inflammation were independent predictors of fatality after vascular events in the dialysis population. We identified BMI, serum albumin, and CRP as the predictors of death after incident vascular disease, although the predictive powers of these markers varied among the types of vascular events. When MI, CI, and CB were combined as incident CVD, lower BMI and higher CRP levels were significant predictors for death among the patients who experienced incident CVD independent of the lipid and other nonlipid variables. Beddhu et al. (18) made similar observations that a low BMI was a predictor of death in hemodialysis patients after acute coronary syndrome. These studies strongly indicate that PEW and inflammation increase the risk of death after CVD by increasing the risk of fatality (13,14).

Although previous studies showed low BMI, low serum albumin, and high CRP levels were predictors for all-cause mortality, it was unknown whether these markers for PEW and inflammation predict incident CVD in the hemodialysis population. This study showed that low serum albumin and high CRP levels were independent predictors of both incident MI and incident CI. Because decline in serum albumin concentration is more closely associated with acute phase proteins rather than dietary protein intake in hemodialysis patients (34), these data may indicate that inflammation was positively associated with incident atherosclerotic CVD in hemodialysis patients. Because BMI correlates positively with both fat mass index and lean mass index in hemodialysis patients (12), a low BMI serves as an integrated index for PEW. In this study, BMI was positively associated with incident MI and inversely with incident CI. Thus, the impact of PEW on incident CVD seems to depend on the type of vascular disease.

We found that a higher level of non–HDL-C or LDL-C was an independent predictor of atherosclerotic CVD in hemodialysis patients. These data may seem to contradict the results of two randomized controlled trials with statin (35,36) that failed to show significant reduction in the composite cardiovascular endpoint in hemodialysis patients. However, the composite cardiovascular endpoints included death from nonatherosclerotic CVD such as congestive heart failure, arrhythmia, and CB. The inclusion of these endpoints must have diluted the true anti-atherosclerotic effects of lipid-lowering. In addition, if a subject received coronary intervention before MI, it was not counted as the primary endpoint, but the secondary endpoint. This must be another cause for underestimating the effects of lipid-lowering. In fact, the risk of ischemic cardiac events including coronary interventions as the second endpoint was significantly reduced by atorvastatin in the 4D trial (35). Taking these facts into consideration, our results do not conflict with the two randomized control trials.

Our study provides another piece of novel information that non–HDL-C was superior to LDL-C as the lipid predictor of MI in hemodialysis patients. This may not be surprising, because non–HDL-C is the sum of cholesterol in LDL and TG-rich lipoproteins, and both LDL and TG-rich lipoproteins are independently associated with atherosclerotic arterial changes in dialysis patients (23). The better prediction by non–HDL-C than LDL-C was also reported for the general population (37) and in the cohort including type 2 diabetes patients (38,39). Non–HDL-C level is an integrated index for atherogenic lipoproteins, and it is not affected by eating (40). Thus, casual blood non–HDL-C seems to be a lipid variable suitable for assessment of risk for incident atherosclerotic CVD, particularly for coronary heart disease, in hemodialysis patients.

This study has several limitations. First, because we detected the incident vascular disease by looking at the change in the history between the year end of 2003 and 2004, we could not take the time to the event or the time to death after the event into consideration. Second, we did not use fasting serum lipids but casual serum lipid values. This might have brought inaccuracy in calculating LDL-C, although non–HDL-C is not affected by eating. Third, no information was available on medication, BP, pulse rate, and smoking. Statin prescription rate was reported to be 7.1% for Japanese dialysis patients in 2000 (41). BP is known to show a U-shaped relationship with mortality in dialysis patients (42). Tachycardia is a predictor of worse outcome in hemodialysis patients (43). Fourth, it is unknown to what extent these results could be applied to hemodialysis patients living in other countries than Japan, because there are considerable international differences in incidence of cardiovascular disease and serum lipid levels in the general populations. Also, in comparison with the United States and European countries, Japanese dialysis patients have lower levels of serum CRP (44), BMI (45), and mortality rates from all-cause (46) and atherosclerotic CVD (47). Thus, these data need to be confirmed in other ethnic groups before being generalized. Finally, the results of this observational cohort study do not necessarily indicate causality as other observational studies.

In conclusion, this study showed a positive association between non–HDL-C and incident vascular disease, especially MI, in a large cohort of hemodialysis patients. Also, higher CRP and lower BMI levels were predictive of higher fatality risk after vascular events. These results indicate the presence of two groups of risk factors contributing to cardiovascular mortality. Further studies are needed to confirm our observations in other ethnic groups.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Part of this work was presented at the XLVII European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplantation Association Congress 2010 in Munich. The authors thank JSDT, the current (Dr. Y. Tsubakihara) and former chairmen of CRDR (Drs. M. Odaka, K. Sawanishi, K. Maeda, and T. Akiba), the principal investigators of all prefectures, and all of the personnel and patients at the institutions participating in this survey.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1. Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR: High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Am J Med 62: 707–714, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alwakeel JS, Al-Suwaida A, Isnani AC, Al-Harbi A, Alam A: Concomitant macro and microvascular complications in diabetic nephropathy. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 20: 402–409, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Manson JE, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Hankinson SE, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE: Body weight and mortality among women. N Engl J Med 333: 677–685, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Volpato S, Leveille SG, Corti MC, Harris TB, Guralnik JM: The value of serum albumin and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in defining mortality risk in older persons with low serum cholesterol. J Am Geriatr Soc 49: 1142–1147, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stevens J, Cai J, Pamuk ER, Williamson DF, Thun MJ, Wood JL: The effect of age on the association between body-mass index and mortality. N Engl J Med 338: 1–7, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Landi F, Onder G, Gambassi G, Pedone C, Carbonin P, Bernabei R: Body mass index and mortality among hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med 160: 2641–2644, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Block G, Horwich T, Fonarow GC: Reverse epidemiology of conventional cardiovascular risk factors in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 43: 1439–1444, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chao FC, Efron B, Wolf P: The possible prognostic usefulness of assessing serum proteins and cholesterol in malignancy. Cancer 35: 1223–1229, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Degoulet P, Legrain M, Reach I, Aime F, Deviries C, Rojas P, Jacobs C: Mortality risk factors in patients treated by chronic hemodialysis. Report of the Diaphane collaborative study. Nephron 31: 103–110, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lowrie EG, Lew NL: Death risk in hemodialysis patients: The predictive value of commonly measured variables and an evaluation of death rate differences between facilities. Am J Kidney Dis 15: 458–482, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iseki K, Yamazato M, Tozawa M, Takishita S: Hypocholesterolemia is a significant predictor of death in a cohort of chronic hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 61: 1887–1893, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kakiya R, Shoji T, Tsujimoto Y, Tatsumi N, Hatsuda S, Shinohara K, Kimoto E, Tahara H, Koyama H, Emoto M, Ishimura E, Miki T, Tabata T, Nishizawa Y: Body fat mass and lean mass as predictors of survival in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 70: 549–556, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nishizawa Y, Shoji T, Ishimura E, Inaba M, Morii H: Paradox of risk factors for cardiovascular mortality in uremia: Is a higher cholesterol level better for atherosclerosis in uremia? Am J Kidney Dis 38: S4–7, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shoji T, Nishizawa Y: Chronic kidney disease as a metabolic syndrome with malnutrition: Need for strict control of risk factors. Intern Med 44: 179–187, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stenvinkel P, Heimburger O, Lindholm B, Kaysen GA, Bergstrom J: Are there two types of malnutrition in chronic renal failure? Evidence for relationships between malnutrition, inflammation and atherosclerosis (MIA syndrome). Nephrol Dial Transplant 15: 953–960, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fouque D, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple J, Cano N, Chauveau P, Cuppari L, Franch H, guarnieri G, Ikizler TA, Kaysen G, Lindholm B, Massy Z, Mitch W, Pineda E, Stenvinkel P, trevino-Becerra A, Wanner C: A proposed nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for protein-energy wasting in acute and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 73: 391–398, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu Y, Coresh J, Eustace JA, Longenecker JC, Jaar B, Fink NE, Tracy RP, Powe NR, Klag MJ: Association between cholesterol level and mortality in dialysis patients: Role of inflammation and malnutrition. JAMA 291: 451–459, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beddhu S, Pappas LM, Ramkumar N, Samore MH: Malnutrition and atherosclerosis in dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 733–742, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Herzog CA, Ma JZ, Collins AJ: Poor long-term survival after acute myocardial infarction among patients on long-term dialysis. N Engl J Med 339: 799–805, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iseki K, Fukiyama K: Clinical demographics and long-term prognosis after stroke in patients on chronic haemodialysis. The Okinawa Dialysis Study (OKIDS) Group. Nephrol Dial Transplant 15: 1808–1813, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Iseki K, Fukiyama K: Long-term prognosis and incidence of acute myocardial infarction in patients on chronic hemodialysis. The Okinawa Dialysis Study Group. Am J Kidney Dis 36: 820–825, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith GL, Masoudi FA, Shlipak MG, Krumholz HM, Parikh CR: Renal impairment predicts long-term mortality risk after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 141–150, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shoji T, Nishizawa Y, Kawagishi T, Kawasaki K, Taniwaki H, Tabata T, Inoue T, Morii H: Intermediate-density lipoprotein as an independent risk factor for aortic atherosclerosis in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1277–1284, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shoji T, Kawagishi T, Emoto M, Maekawa K, Taniwaki H, Kanda H, Nishizawa Y: Additive impacts of diabetes and renal failure on carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 153: 257–258, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shoji T, Emoto M, Shinohara K, Kakiya R, Tsujimoto Y, Kishimoto H, Ishimura E, Tabata T, Nishizawa Y: Diabetes mellitus, aortic stiffness, and cardiovascular mortality in end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 2117–2124, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shoji T, Emoto M, Tabata T, Kimoto E, Shinohara K, Maekawa K, Kawagishi T, Tahara H, Ishimura E, Nishizawa Y: Advanced atherosclerosis in predialysis patients with chronic renal failure. Kidney Int 61: 2187–2192, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shinohara K, Shoji T, Tsujimoto Y, Kimoto E, Tahara H, Koyama H, Emoto M, Ishimura E, Miki T, Tabata T, Nishizawa Y: Arterial stiffness in predialysis patients with uremia. Kidney Int 65: 936–943, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kimoto E, Shoji T, Shinohara K, Hatsuda S, Shinohara K, Kimoto E, Tahara H, Koyama H, Emoto M, Ishimura E, Miki T, Tbata T, Nishizawa Y: Regional arterial stiffness in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2245–2252, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nakai S, Masakane I, Shigematsu T, Hamano T, Yamagata K, Watanabe Y, Itami N, Ogata S, Kimata N, Shinoda T, Syouji T, Suzuki K, Taniguchi M, Tsuchida K, Nakamoto H, Nishi S, Nishi H, Hashimoto S, Hasegawa T, Hanafusa N, Fujii N, Marubayashi S, Morita O, Wakai K, Wada A, Iseki K, Tsubakihara Y: An overview of regular dialysis treatment in Japan (as of 31 December 2007). Ther Apher Dial 13: 457–504, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shinzato T, Nakai S, Akiba T, Yamazaki C, Sasaki R, Kitaoka T, Kubo K, Shinoda T, Kurokawa K, Marumo F, Sato T, Maeda K: Current status of renal replacement therapy in Japan: Results of the annual survey of the Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 11: 2143–2150, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ: Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 32: S112–119, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nishizawa Y, Shoji T: Does dialysis treatment promote atherosclerosis?. Jap J Clin Dial (Rinsho Toseki) 12: 1133–1144, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shoji T, Nishizawa Y: Plasma lipoprotein abnormalities in hemodialysis patients: Clinical implications and therapeutic guidelines. Ther Apher Dial 10: 305–315, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kaysen GA, Dubin JA, Muller HG, Rosales L, Levin NW, Mitch WE; HEMO Study Group NIDDK: Inflammation and reduced albumin synthesis associated with stable decline in serum albumin in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 65: 1408–1415, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wanner C, Krane V, Marz W, Olschewski M, Mann JF, Ruf G, Ritz E; German Diabetes and Dialysis Study Investigators: Atorvastatin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 353: 238–248, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fellstrom BC, Jardine AG, Schmieder RE, Holdaas H, Bannister K, Beutler J, Chae DW, Chevaile A, Cobbe SM, Grönhagen-Riska C, De Lima JJ, Lins R, Mayer G, McMahon AW, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Samuelsson O, Sonkodi S, Sci D, Süleymanlar G, Tsakiris D, Tesar V, Todorov V, Wiecek A, Wüthrich RP, Gottlow M, Johnsson E, Zannad F; AURORA Study Group: Rosuvastatin and cardiovascular events in patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 360: 1395–1407, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Di Angelantonio E, Sarwar N, Perry P, Kaptoge S, Ray KK, Thompson A, Wood AM, Lewington S, Sattar N, Packard CJ, Collins R, Thompson SG, Danesh J: Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA 302: 1993–2000, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu J, Sempos C, Donahue RP, Dorn J, Trevisan M, Grundy SM: Joint distribution of non-HDL and LDL cholesterol and coronary heart disease risk prediction among individuals with and without diabetes. Diabetes Care 28: 1916–1921, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lu W, Resnick HE, Jablonski KA, Jones KL, Jain AK, Howard WJ, Robbins DC, Howard BV: Non-HDL cholesterol as a predictor of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: The strong heart study. Diabetes Care 26: 16–23, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wanner C, Krane V: Non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: A target of lipid-lowering in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 41: S72–75, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mason NA, Bailie GR, Satayathum S, Bragg-Gresham JL, Akiba T, Akizawa T, Combe C, Rayner HC, Saito A, Gillespie BW, Young EW: HMG-coenzyme a reductase inhibitor use is associated with mortality reduction in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 45: 119–126, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zager PG, Nikolic J, Brown RH, Campbell MA, Hunt WC, Peterson D, Van Stone J, Levey A, Meyer KB, Klag MJ, Johnson HK, Clark E, Sadler JH, Teredesai P: “U” curve association of blood pressure and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Medical Directors of Dialysis Clinic, Inc. Kidney Int 54: 561–569, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Iseki K, Nakai S, Yamagata K, Tsubakihara Y: Tachycardia as a predictor of poor survival in chronic haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant September 3, 2010. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kaysen GA: Biochemistry and biomarkers of inflamed patients: Why look, what to assess. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4 Suppl 1: S56–S63, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Inrig JK, Sun JL, Yang Q, Briley LP, Szczech LA: Mortality by dialysis modality among patients who have end-stage renal disease and are awaiting renal transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 774–779, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Goodkin DA, Young EW, Kurokawa K, Prutz KG, Levin NW: Mortality among hemodialysis patients in Europe, Japan, and the United States: case-mix effects. Am J Kidney Dis 44: 16–21, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yoshino M, Kuhlmann MK, Kotanko P, Greenwood RN, Pisoni RL, Port FK, Jager KJ, Homel P, Augustijn H, de Charro FT, Collart F, Erek E, Finne P, Garcia-Garcia G, Grönhagen-Riska C, Ioannidis GA, Ivis F, Leivestad T, Løkkegaard H, Lopot F, Jin DC, Kramar R, Nakao T, Nandakumar M, Ramirez S, van der Sande FM, Schön S, Simpson K, Walker RG, Zaluska W, Levin NW: International differences in dialysis mortality reflect background general population atherosclerotic cardiovascular mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3510–3519, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]