Abstract

The PROSITE database consists of a large collection of biologically meaningful signatures that are described as patterns or profiles. Each signature is linked to documentation that provides useful biological information on the protein family, domain or functional site identified by the signature. The PROSITE web page has been redesigned and several tools have been implemented to help the user discover new conserved regions in their own proteins and to visualize domain arrangements. We also introduced the facility to search PDB with a PROSITE entry or a user’s pattern and visualize matched positions on 3D structures. The latest version of PROSITE (release 18.17 of November 30, 2003) contains 1676 entries. The database is accessible at http://www.expasy.org/prosite/.

INTRODUCTION

A popular way to identify similarity between proteins is to perform a pairwise alignment. When the identity is >40% this method gives good results. However, the weakness of the pairwise alignment is that no distinction is made between an amino acid at a crucial position (like an active site) and an amino acid with no critical role. A multiple sequence alignment (MSA) gives a more general view of a conserved region by providing a better picture of the most conserved residues, which are usually essential for the protein function. The various amino acids can then be weighed according to their degree of conservation. Several databases have developed their own methods (descriptors) based on MSA in order to identify conserved regions. A search performed on these databases is generally more sensitive than a pairwise alignment and can help identify very remote similarity (<20%).

The PROSITE database uses two kinds of descriptor to identify conserved regions, patterns and generalized profiles, which each have their own strengths and weaknesses defining their area of optimum application (1).

(i) A pattern or regular expression is a quantitative descriptor: it either matches or does not. Therefore a good pattern is usually located in a short well-conserved region. Such regions are typically enzyme catalytic sites, prosthetic group attachment sites (haem, pyridoxal phosphate, biotin, etc.), metal ion binding amino acids, cysteines involved in disulfide bonds or regions involved in binding a molecule. Even though the scope of a regular expression is limited to these particular biological regions, patterns are still very popular because of their intelligibility for users.

(ii) A profile is a table of position-specific amino acid weights and gap costs. Various methods can be used to fill a profile table from a multiple alignment. Most frequently, a substitution matrix is used to convert a residue frequency distribution into weights, but alternative methods can be applied including structure-based approaches and methods involving hidden Markov modelling (2–4). These weights (also referred to as scores) are used to calculate a similarity score for any alignment between a profile and a sequence, or part of a profile and a sequence. An alignment with a similarity score higher than or equal to a given threshold value constitutes a motif occurrence. This threshold is estimated by calibrating the profile against a randomized protein database. The normalization procedure used for PROSITE profiles makes the normalized scores independent of the database size, allowing the comparison of scores from different searches (5). The quantitative behaviour of a profile allows the acceptance of a mismatch at a highly conserved position if the rest of the sequence displays a sufficiently high level of similarity and therefore allows the detection of poorly conserved domains such as immunoglobulin, SH2 or SH3. Another advantage of profiles over patterns is that they are not confined to small regions with high sequence similarity. Rather, they attempt to characterize a protein family or domain over its entire length.

PROSITE ANNOTATION AND QUALITY CONTROL

Each PROSITE signature is linked to an annotation document where the user can find information on the protein family or domain detected by the signature: origin of its name, taxonomic occurrence, domain architecture, function, 3D structure, main characteristics of the sequence and some references. Recently, for families or domains whose structure is known, a direct link to a representative PDB entry is provided in the documentation, in order to make the description of the 3D structure more comprehensible. All the biological information about a protein family or domain should also be used to evaluate the pertinence of matches with patterns and profiles. If the user has some information about their sequence that is inconsistent with the description of the motif detected, the match should be considered with caution.

The annotation document also contains direct information about the motif descriptors: for patterns, amino acid residues involved in the catalytic mechanism, metal ion or substrate binding, or conserved post-translational modifications are indicated. For profiles, it is stated whether they cover the entire domain or protein or only part of it. Finally, the sensitivity and specificity of the motif is also indicated, as well as an expert to contact, if any.

Biologically meaningful information on specific amino acids can also be found at the CC /SITE line in signature entries. This qualifier is used to indicate the position of an ‘interesting’ site in a pattern or a profile. For example, if a pattern includes an active site residue, the /SITE qualifier is used to indicate the position of that residue in the pattern. Binding sites and disulfide bridges are also indicated. The ps_scan program, the reference tool to scan PROSITE (6), is able to highlight these positions in a matched region.

A match list of Swiss-Prot entries identified by the signature is also provided. Each protein entering Swiss-Prot is checked for the occurrence of PROSITE patterns or profiles and a match status is assigned (‘true’ or ‘false positive’ or ‘unknown’). Proteins that are known to contain the domain but not identified by the signature are also added to the list with the status ‘false negative’. Because this match list has been verified manually, it can be used to evaluate the specificity of a given signature. This tight connection with Swiss-Prot also benefits the Swiss-Prot annotation. Some particular Swiss-Prot lines, which refer to the domain organization in the protein, are automatically annotated with PROSITE profiles.

The PROSITE descriptors and documentation can also be accessed through InterPro, which largely exploits the detailed family annotation provided by PRINTS (7) and PROSITE. InterPro (8) provides an integrated view of several domain databases and offers a large choice of methods to identify conserved regions.

IMPROVEMENT OF THE PROFILE METHOD

Repeat

Proteins can contain a single copy of a particular domain, but in many cases two or more copies are present. The identification of some of these repetitive elements presents additional difficulties compared with the detection of autonomous domains, because they are generally short in size and highly divergent.

We have developed a new approach to increase the sensitivity of PROSITE profiles for repeats. Our method is based on the determination of a lower acceptance threshold to detect highly divergent repeats. The computed lower acceptance threshold is used to increase the sensitivity of repeat detection within proteins as well as for the characterization of new family members. The method applied to 12 different families allowed the detection of more than 5000 repeat units and 200 proteins in Swiss-Prot previously not recognized by PROSITE.

Structural alignment

The sensitivity of a profile is strongly dependent on the quality of the starting sequence alignment. Usually ClustalW (9) or T-Coffee (10) are used to construct the MSA. But when sequences are too divergent it can be useful to integrate structural information in the MSA. Several of our profiles have been built by a mixture of classical alignment and structural alignment with the help of T-Coffee or by pure structural alignment provided by the DALI algorithm (11). These methods have been used for the construction of several profiles, e.g. the ABC transporter, the Ig-fold and the aminoacyl-transfer RNA synthetase class-II profiles. We have observed that structural information is often useful for very divergent domains or families, but that it is of small benefit for strongly conserved sequences.

Profile construction

To fill in our profile table from a MSA we generally use a symbol comparison table to convert a residue frequency distribution into weights, but in some particular cases a probabilistic model associated with a Dirichlet mixture can be more sensitive (12). For such an approach we use the HMMER package (13) to build the profile and convert it into PROSITE format profile with pftools (3). About 3% of our profiles have been built with this method.

NEW IMPLEMENTATION ON THE WEB PAGE

Our website was redesigned to help the user identify conserved regions in their own protein. The user can now build their own pattern from an unaligned set of sequences using the PRATT algorithm (14). The pattern can then be scanned on the non-redundant database UniProt (Swiss-Prot + TrEMBL) (15). The search space can be reduced to a specific taxon. The matched sequences can be visualized as a shaded MSA, as a taxonomic tree or as a graphical view of the domain arrangement of the matched proteins. The user can also retrieve the full-length sequences in FASTA or Swiss-Prot format. The pattern can also be visualized on 3D structures if the selected database is PDB: the region matched by the pattern is highlighted and can thus easily be located on the structure (see Fig. 1). As patterns do not produce scores, as do HMMs or profiles, it is difficult to evaluate the significance of a match. To circumvent this problem we allow the user to randomize non-redundant databases. A scan against any of these databases will give a raw estimate of the amount of matches produced by chance. We provide two methods to randomize databases. The first method, which simply reverses the order of sequences, is fast and efficient if the pattern is not palindromic. For this type of regular expression the user must use a shuffled randomization mode where windows of 20 amino acids are shuffled in the sequence (5).

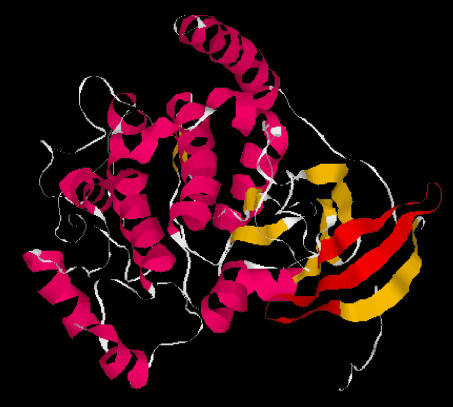

Figure 1.

A search on the PDB database with the PROSITE pattern PS00107 (directed against the ATP binding region of the kinase domain) was performed on the ScanProsite page. The pattern identified 221 matches. The 1CTP entry was selected to visualize the position of the pattern on the 3D structure. The ATP binding region is highlighted in red. The ScanProsite page uses RasMol (16) scripts to produce images. An interactive view with the Chime program is also provided.

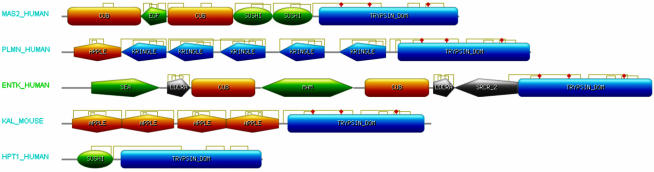

The webview of the PROSITE documentation also contains new information. When a 3D structure is described in the text, a direct link to a 3D image of the domain is provided. The Swiss-Prot match list of each signature can be visualized as a multiple alignment, or as a taxonomic distribution graph. For PROSITE profiles, a domain arrangement view is also provided where active sites and disulfide bridges annotated in Swiss-Prot entries are superimposed on PROSITE domains (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Five proteins have been extracted from the domain view of the trypsin profile (PS50240) match list. Disulfide bridges are represented as red inverted hooks and active sites as red diamonds. The labeling of the active site residues allows the rapid detection of domains that may have lost their enzymatic activity. The fifth example is the human haptoglobin, a clearly related serine protease but with no enzymatic activity.

HOW TO OBTAIN PROSITE

PROSITE is freely available to academic users. As of release 16, the documentation entries are copyright. To obtain a licence, commercial users should contact The Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics by email: license@isb-sib.ch or its commercial representative: Geneva Bioinformatics (GeneBio) SA, Case Postale 210, CH-1211 Geneva 12, Switzerland, phone: +41 22 702.99.00; fax: +41 22 702.99.99; email: info@genebio.com. Weekly updates of PROSITE are available on our FTP server: ftp://ftp.expasy.org/databases/prosite/release_ with_updates/. PROSITE is also accessible from the Hits page (17): http://hits.isb-sib.ch/. Frame-tolerant scans can be performed at the following address (18): http://www.isrec.isb-sib.ch/software/PFRAMESCAN_form.html.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Tania Lima for the correction of the manuscript. PROSITE is supported by grant no. 3100-63879.00 from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sigrist C.J.A., Cerutti,L., Hulo,N., Gattiker,A., Falquet,L., Pagni,M., Bairoch,A. and Bucher,P. (2002) PROSITE: a documented database using patterns and profiles as motif descriptors. Brief. Bioinform., 3, 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gribskov M., Luthy,R. and Eisenberg,D. (1990) Profile analysis. Methods Enzymol., 183, 146–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bucher P., Karplus,K., Moeri,N. and Hofmann,K. (1996) A flexible motif search technique based on generalized profiles. Comput. Chem., 20, 3–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hofmann K. (2000) Sensitive protein comparisons with profiles and hidden Markov models. Brief. Bioinform., 1, 167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pagni M. and Jongeneel,C.V. (2001) Making sense of score statistics for sequence alignments. Brief. Bioinform., 2, 51–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gattiker A., Gasteiger,E. and Bairoch,A. (2002) ScanProsite: a reference implementation of a PROSITE scanning tool. Appl. Bioinform., 1, 107–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attwood T.K., Bradley,P., Flower,D.R., Gaulton,A., Maudling,N., Mitchell,A.L., Moulton,G., Nordle,A., Paine,K., Taylor,P. et al. (2003) PRINTS and its automatic supplement, prePRINTS. Nucleic Acids Res., 31, 400–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulder N.J., Apweiler,R., Attwood,T.K., Bairoch,A., Barrell,D., Bateman,A., Binns,D., Biswas,M., Bradley,P., Bork,P. et al. (2003) The InterPro Database, 2003 brings increased coverage and new features. Nucleic Acids Res., 31, 315–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson J.D., Higgins,D.G. and Gibson,T.J. (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Notredame C., Higgins,D.G. and Heringa,J. (2000) T-Coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol., 302, 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holm L. and Sander,C. (1993) Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J. Mol. Biol., 233, 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sjolander K., Karplus,K., Brown,M., Hughey,R., Krogh,A., Mian,I.S. and Haussler,D. (1996) Dirichlet mixtures: a method for improved detection of weak but significant protein sequence homology. Comput. Appl. Biosci., 12, 327–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eddy S.R. (1998) Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics, 14, 755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonassen I. (1997) Efficient discovery of conserved patterns using a pattern graph. Comput. Appl. Biosci., 13, 509–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apweiler R. Bairoch,A., Wu,C.H., Barker,W.C., Boeckmann,B., Ferro,S., Gasteiger,E., Huang,H., Lopez,R., Magrane,M. et al. (2004) UniProt: the Universal Protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res., 32, D115–D119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sayle R.A. and Milner-White,E.J. (1995) RASMOL: biomolecular graphics for all. Trends Biochem. Sci., 20, 374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pagni M., Iseli,C., Junier,T., Falquet,L., Jongeneel,V. and Bucher,P. (2001) trEST, trGEN and Hits: access to databases of predicted protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 148–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falquet L., Pagni,M., Bucher,P., Hulo,N., Sigrist,C.J.A., Hofmann,K. and Bairoch,A. (2002) The PROSITE database, its status in 2002. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 235–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]