Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of our study was to examine the relationship between ankle dorsiflexion (DF) range of motion (ROM) and stiffness measured at rest (passively) and plantar loading during gait in individuals with and without diabetes mellitus (DM) and sensory neuropathy. Specifically, we sought to address three questions for this at-risk patient population: (1) Does peak passive DF ROM predict ankle DF ROM used during gait? (2) Does passive ankle stiffness predict ankle stiffness used during gait? (3) Are any of the passive or gait-related ankle measures associated with plantar loading?

Methods

Ten subjects with DM and 10 age and gender matched non-diabetic control subjects participated in this study. Passive ankle DF ROM and stiffness were measured with the Iowa Ankle ROM device. Kinematic, kinetic and plantar pressure data were collected as subjects walked at 0.89 m/s.

Results

We found that subjects with DM have reduced passive ankle DF ROM and increased stiffness compared to non-diabetic control subjects, however, subjects with DM demonstrated ankle motion, stiffness and plantar pressures, similar to control subjects, while walking at the identical speed, 0.89 m/s (2 mph). These data indicate that clinical measures of heel cord tightness and stiffness do not represent ankle motion or stiffness utilized during gait. Our findings suggest that subjects with DM utilize strategies such as shortening their stride length and reducing their push-off power to modulate plantar loading.

Keywords: Ankle ROM, Stiffness, Diabetes, Gait, Loading

1. Introduction

Abnormal plantar loading due to foot floor interaction [1] is thought to contribute to the development of foot ulcers in individuals with diabetes mellitus (DM) where the estimated incidence is up to 20% of all individuals with DM [2]. Inability to heal foot ulcers or prevent recurrence contributes to progression of the local pathology, leading to the high rate of amputation seen in individuals with DM. Over 50% of non-traumatic lower limb amputations are performed on individuals with DM [3]. Along with grave consequences affecting health and functional abilities [4], foot ulcers and amputation are often harbingers of personal and financial hardship. Factors contributing to increased loading on the plantar aspect of the foot and thus the potential development of foot ulcers are therefore of considerable interest.

Recent studies implicate limited passive dorsiflexion (DF) range of motion (ROM) and increased passive ankle stiffness as key factors contributing to increased plantar loading [5–10]. Limited ankle DF ROM and/or increased stiffness may result from the effects of longstanding hyperglycemia on connective tissue [11] and are hypothesized to restrain forward progression of the tibia on the fixed foot during the stance phase of walking. This, in turn, is believed to result in prolonged and excessive weight bearing stress under the metatarsal heads.

Evidence supporting the postulated relationship between ankle flexibility and plantar loading is limited, predominantly coming from studies demonstrating improved ulcer healing following Achilles tendon lengthening surgery [5,6,8]. These studies reported 9–18° improvement in DF ROM with concomitant 27–46% reduction in forefoot plantar pressure 2–7 months following tendo-Achilles lengthening [5,9]. However, after surgery, subjects may modulate foot pressures by altering their gait using different approaches, such as preferentially loading the non-operated limb, changing walking strategy and reducing walking speed. In these circumstances, factors other than intervention would influence the reported relationship between ankle DF ROM and plantar loading. Further, longitudinal studies of subjects who have undergone tendon Achilles lengthening demonstrate a disconnect between passive ankle DF ROM and loading [9]. Following this procedure, improvements in ankle DF ROM are maintained 7 months post-operatively, however, plantar loading increase to values close to those measured before Achilles tendon lengthening.

Cross-sectional studies seeking to examine the relationship between mechanical properties of the ankle and plantar loading indicate that subjects with reduced passive ankle ROM sustain significantly higher plantar pressures during walking [10,12,13]. However, these studies do not control walking speed, which can influence both ankle motion [14,15] and plantar loading during gait [16–18]. Walking speed thus emerges as a confounding factor, rendering interpretation of purported results difficult.

Experimental studies investigating structural and functional predictors of regional plantar loading reveal that subjects who tend to walk with larger dynamic ankle ROM experience higher forefoot plantar pressures [19]. These findings, albeit from non-diabetic individuals, highlight the importance of dynamic ROM; however they do not relate dynamic ROM to available (passive)ROM. The relationship between dynamic ROM utilized in gait and passive ROM thus emerges as an important potential factor contributing to plantar loading but has not been elucidated in individuals with DM.

The purpose of our study was to examine the relationship between ankle DF ROM and stiffness measured at rest (passively) and plantar loading during gait in individuals with and without DM and neuropathy. Specifically, we sought to address three questions: (1) Does peak passive DF ROM predict ankle DF ROM used during gait? (2) Does passive ankle stiffness predict ankle stiffness used during gait? (3) Are any of the passive or gait-related ankle measures associated with plantar loading? Compared to the control group, we hypothesized that subjects with DM would demonstrate lower passive DF ROM and higher stiffness. Due to differences in impairments, we hypothesized that passive ankle DF ROM and stiffness would predict ankle DF ROM and stiffness during gait in individuals with DM but not in non-diabetic individuals. We expected that passive ankle DF ROM and passive ankle stiffness would be associated with plantar loading in subjects with DM but not in non-diabetic individuals.

2. Methods

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. Subjects were recruited from the Diabetic Foot Clinic with the following inclusion criteria: diagnosis of DM, no current or history of previous ipsilateral foot ulcer, great toe or transmetatarsal amputation, absence of ipsilateral or contralateral Charcot neuroarthropathy. Presence of neuropathy was documented using 5.07 Semmes–Weinstein monofilaments. All subjects in the DM group showed loss of protective sensation [20]. Subjects in the non-diabetic control group were matched in age and gender to subjects with DM and were screened for lower extremity pain or musculoskeletal pathology or history thereof in the last 6 months. Ten subjects with DM (mean age: 56 ± 11 years; mean body mass: 96.6 ± 31.2 kg; mean height: 1.74 ± 0.1 m; M:F ratio: 6:4) and 10 non-diabetic control subjects (mean age: 54 ± 8 years; mean body mass: 76 ± 14.8 kg; mean height: 1.71 ± 0.09 m; M:F ratio: 6:4) participated in this study. The study and control groups did not differ in age (p = 0.52), body mass (p = 0.09) or height (p = 0.53). Subject characteristics documented in the DM group included: average duration of DM (20 ± 11 years), type of DM: 80% Type 2 DM and glycemic control (most recent HbA1C: 8.1 ± 1.2%).

2.1. Passive testing

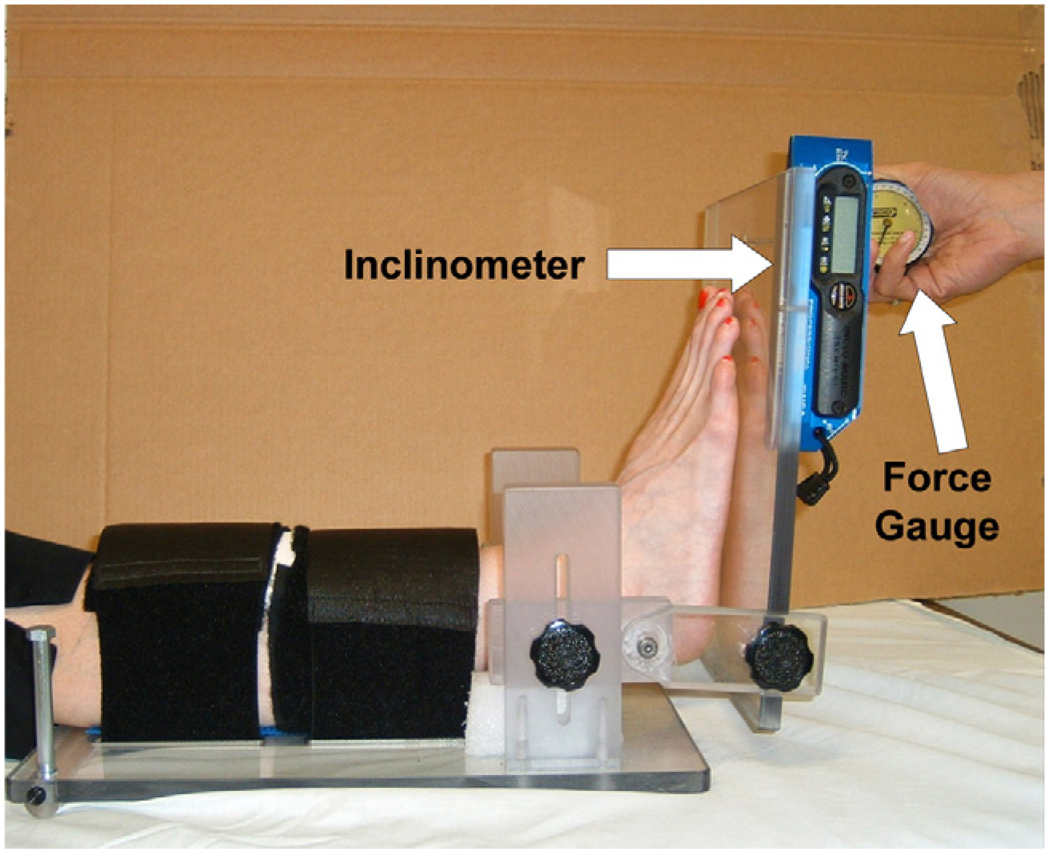

Passive ankle ROM and stiffness at specific torque levels [21,22] was measured using the Iowa Ankle ROM device, which has been shown to be valid and reliable [23]. Detailed description of the device and methods are provided in ref. [23]. Briefly, subjects were positioned supine with the knee extended; their leg was supported by a base plate and a foam block; and secured by Velcro straps. The sole of their foot was positioned so contact was maintained with a translucent Plexiglas foot plate throughout testing. The axis of rotation of the device was then adjusted in the antero-posterior and superior/inferior directions to approximate the ankle axis of rotation determined by palpation of the distal tips of the medial and lateral malleoli [24]. Torques of 15, 20 and 25 N m was applied using a hand held force gauge and resultant angular kinematics were measured using a digital inclinometer. Fig. 1 shows the apparatus and setup. The inclinometer was referenced to the tibial crest and then mounted on the foot plate which was parallel to the sole of the foot. Three cycles of testing were recorded at each force level. Next, the knee was flexed to approximately 20° to simulate the magnitude of knee flexion attained during gait [25] and ROM testing was repeated at the three force levels. Passive ankle stiffness was calculated as the slope of the resultant curves over the 15–25 N m intervals.

Fig. 1.

Apparatus and setup for ankle ROM testing.

2.2. Gait testing

Kinematic and kinetic data were recorded as subjects walking along 10 m walkway at 0.89 m/s (2 mph) in their customary footwear. In designing this study, we decided to allow all subjects to wear their customary footwear and control walking speed. Since almost all walking is performed in shoewear, we thought the continuance of this practice in our study best reflected real life situation and would confer external validity to the study. Previous studies have documented walking velocities between 0.77 and 1.26 m/s in subjects with DM [12,26,27], therefore 0.89 m/s (2 mph) was chosen as a comfortable walking speed, representative of preferred walking speed in subjects with DM. Walking speed was controlled in this study because the self-selected walking speeds in subjects with DM and neuropathy are typically significantly slower than non-diabetic controls [12,28,29]. Walking speed influences ankle kinematics and kinetics [14,15] and also differentially affects plantar pressures in different regions of the foot [16–18].

Kinematic data were recorded at 60 Hz using an active marker system (Optrotrak, NDI, Waterloo, Canada). Three infra-red markers were placed in a non-collinear arrangement on the subject’s foot (over shoe), leg and thigh segments. Kinetic data were collected at 240 Hz using a forceplate embedded in the walkway (Kistler Inc., NY). Plantar pressure data were collected at 50 Hz using pressure sensitive insoles (Pedar, Novel Inc., Minneapolis, MN).

Kinematic and kinetic data were processed using Kingait (Mishac Kinetics, University of Waterloo, Canada) software. Kinetic data were low pass filtered at 8 Hz, kinematic data were low pass filtered with a cut-off frequency of 6 Hz using a fourth order Butterworth filter. Anatomical coordinate systems were established using standard criteria [30]. Sagittal ankle kinematics and kinetics were calculated. Peak dorsiflexion achieved during gait was obtained using sagittal ankle kinematics. Duration of second rocker was identified. Ankle stiffness during second rocker was defined using the method defined by Davis and DeLuca [31]. The magnitude of plantar loading was quantified as the peak pressure sustained under the metatarsal head region in the forefoot during stance.

2.3. Data analysis

A two-sample t-test was used to assess differences between the two groups (α = 0.05). In addition to the hypotheses outlined above, associations between subject characteristics and passive measures were examined to rule out the influence of subject characteristics on passive measures. Pearson product moment correlation (r) was used to assess the relationship between variables of interest. Statistical significance (Ho: ρ = 0) and equality of correlations (Ho: ρ1 = ρ2) were assessed using approximate tests based on Fisher’s Z transformation (α = 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Passive testing

Subjects with DM showed significantly lower peak passive dorsiflexion and higher passive ankle stiffness compared to age matched control subjects (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of passive and gait-related measures

| DM | Control | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak passive DF (°) | 6.4 ± 6.9 | 19.3 ± 3.9 | <0.001 |

| Peak passive DFKF (°) | 13.1 ± 4.2 | 24.1 ± 5.5 | <0.001 |

| Peak DF during gait (°) | 9.9 ± 2.0 | 11.8 ± 2.7 | 0.099 |

| Peak knee flexion in mid-stance (°) | 12.5 ± 6.6 | 14.8 ± 8.8 | 0.167 |

| Passive ankle stiffness (N m/degree) | 1.5 ± 0.49 | 1.042 ± 0.56 | 0.001 |

| Passive ankle stiffnessKF (N m/degree) | 1.508 ± 0.43 | 1.021 ± 0.47 | 0.04 |

| Ankle stiffness during second rocker (N m/degree) | 6.526 ± 1.3 | 6.161 ± 1.753 | 0.603 |

| Stride length (m) | 1.06 ± 0.1 | 1.21 ± 0.07 | 0.001 |

| Peak Pressure (N/cm2) | 27.2 ± 6.1 | 24.6 ± 1.5 | 0.207 |

| Peak plantar flexor moment (N m/kg) | 1.21 ± 0.18 | 1.40 ± 0.25 | 0.06 |

| Peak dorsiflexor moment (N m/kg) | 0.19 ± 0.12 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 0.383 |

| Peak ankle sagittal power (N m/(kg s)) | 1.64 ± 0.47 | 2.00 ± 0.43 | 0.08 |

| Walking velocity (m/s) | 0.91 ± 0.07 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 0.343 |

Superscript ‘KF’ indicates knee flexed condition.

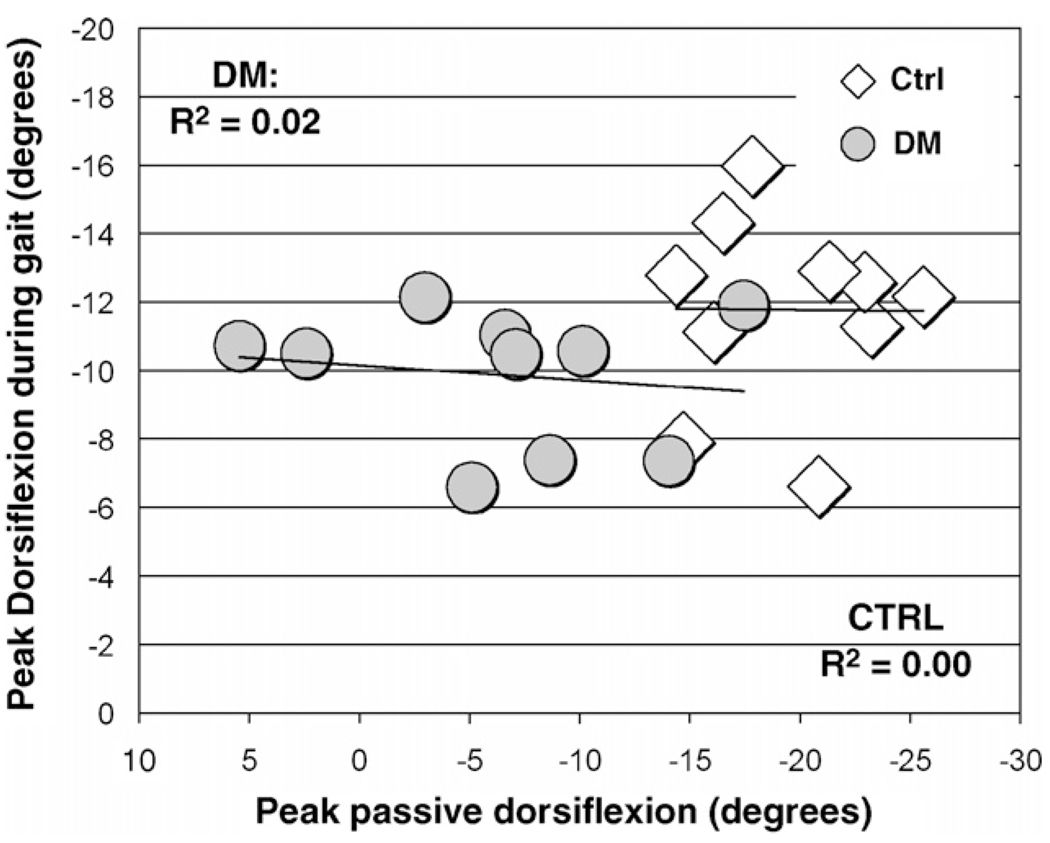

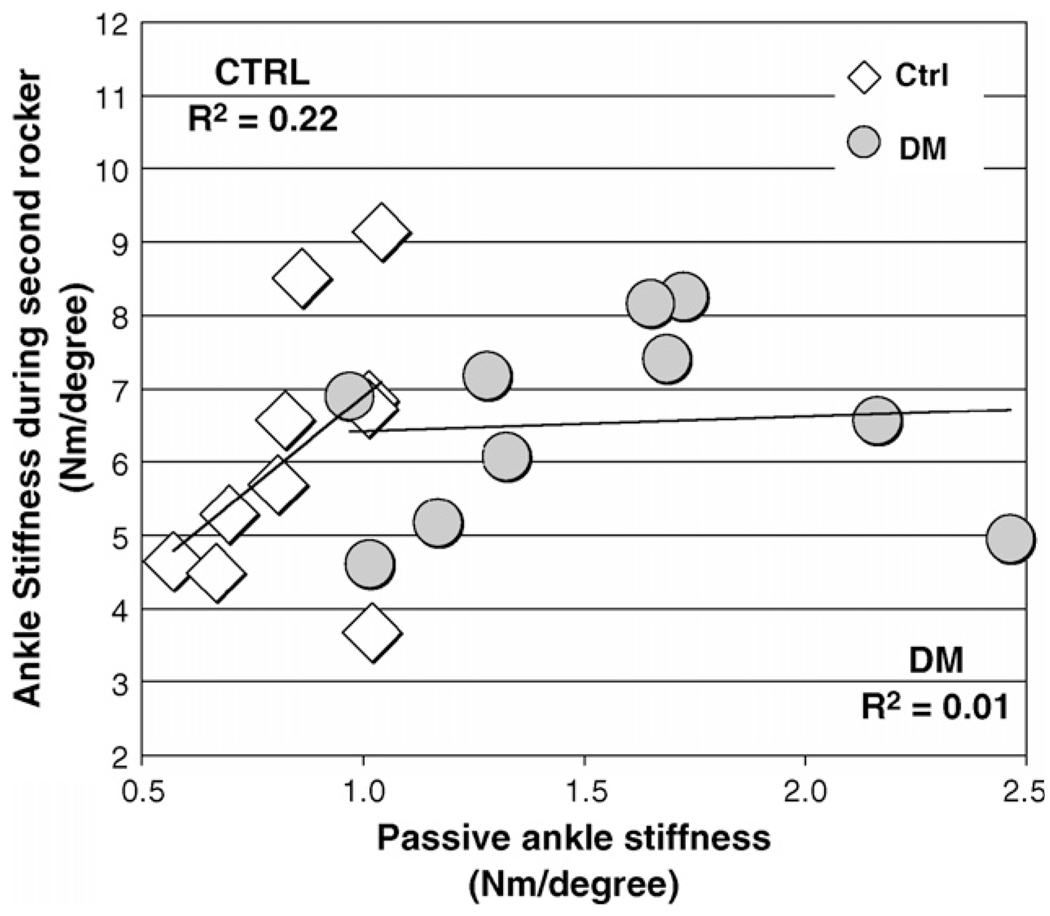

Peak passive ankle dorsiflexion was not associated with peak ankle dorsiflexion attained during gait in either group (Ho: ρ = 0, p = 0.67 and 0.98, DM and control groups, respectively, Ho: ρ1 = ρ2, p = 0.49; Fig. 2). Passive ankle stiffness was not significantly associated with ankle stiffness during second rocker (Ho: ρ = 0, p = 0.84 and 0.17, DM and control groups, respectively, Ho: ρ1 = ρ2, p = 0.20; Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Relationship between passive ankle stiffness and dorsiflexion ankle stiffness utilized during second rocker.

Fig. 3.

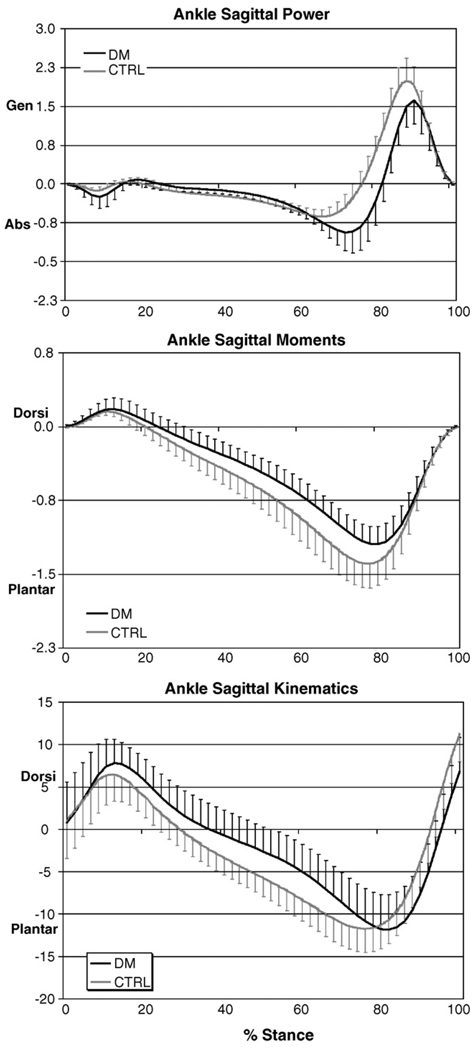

Group mean ± S.D. for sagittal ankle power (W/kg), moment (N m/kg) and kinematics (°) during stance phase.

Glycemic control and duration of DM showed fair association with ankle stiffness (Table 2, electronic addendum).

Table 2.

Summary of associations between subject characteristics and passive ankle stiffness and DF ROM

| DM | Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stiffness | ROM | Stiffness | ROM | |

| Age | r = −0.36, p = 0.31 | r = 0.46, p = 0.18 | r = 0.28, p = 0.58 | r = 0.19, p = 0.43 |

| Body mass | r = 0.22, p = 0.54 | r = −0.15, p = 0.64 | r = 0.41, p = 0.20 | r = −0.42, p = 0.18 |

| Duration of DM | r = 0.55, p = 0.04 | r = 0.33, p = 0.2 | ||

| HbA1C (%) | r = 0.54, p = 0.08 | r = 0.28, p = 0.42 | ||

3.2. Gait testing

Peak dorsiflexion attained during gait, ankle stiffness during second rocker and peak plantar pressure at the forefoot did not differ between groups as they walked at identical speed (Table 1). Subjects in the control group showed trends towards higher peak plantarflexor moment and peak ankle power generation in the sagittal plane (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Relationship between passive ankle dorsiflexion and dorsiflexion utilized during gait.

Passive ankle stiffness, peak passive dorsiflexion, peak dorsiflexion used in gait and ankle stiffness used in gait did not show a significant relationship with peak forefoot plantar pressures in either group (Table 3). Stride length was associated with plantar pressure in both groups. Stride length was associated with ankle stiffness during second rocker and total ankle ROM utilized during gait in subjects with DM but not in non-diabetic control subjects (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of Pearson’s product moment correlation to assess relationships between variables of interest in subjects with and without DM (r1 and r2, respectively)

| Variables of interest | DM, r1 | Control, r2 | |Z| | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak passive DF | Gait DF | −0.150 | −0.007 | 0.270 |

| Peak passive DF KF | Gait DF | 0.145 | 0.158 | 0.025 |

| Passive stiffness | Gait stiffness | 0.075 | 0.472 | 0.843 |

| Passive stiffnessKF | Gait stiffness | −0.017 | 0.14 | 0.295 |

| Peak passive DF | Forefoot PP | −0.512 | 0.457 | 1.981 |

| Peak passive DFKF | Forefoot PP | 0.065 | −0.46 | 1.052 |

| Gait DF | Forefoot PP | 0.134 | 0.317 | 0.362 |

| Passive stiffness | Forefoot PP | −0.501 | 0.433 | 1.897 |

| Passive stiffnessKF | Forefoot PP | −0.273 | −0.13 | 0.279 |

| Gait stiffness | Forefoot PP | 0.020 | 0.588 | 1.225 |

| Stride length | Forefoot PP | 0.708 | 0.656 | 0.182 |

| AROM | Stride length | 0.732 | −0.403 | 2.577 |

| Gait stiffness | Stride length | 0.769 | −0.396 | 2.688 |

Superscript ‘KF’ indicates knee flexed condition; PP indicates peak pressure. The test |Z| ≥ z0.025 has a critical value of 2.57 and assesses equality of the correlations (Ho: ρ1 = ρ2).

4. Discussion

The main findings of our study demonstrated that subjects with DM have reduced passive ankle DF ROM and increased passive stiffness compared to non-diabetic control subjects. To our knowledge, this is the first reported study showing both increased stiffness and reduced dorsiflexion ROM in subjects with DM. However, in spite of differences in passive ankle DF ROM and stiffness, subjects with DM demonstrated ankle motion, stiffness and plantar pressures, similar to control subjects, while walking at the same speed, 0.89 m/s (2 mph). While neither passive nor dynamic DF ROM or ankle stiffness were significantly associated with plantar loading, stride length was positively associated with plantar pressure in both groups.

Clinical measures of passive ankle DF ROM and stiffness obtained in this study are consistent with previous reports documenting reduced ankle DF ROM [10,26] and increased stiffness [22] in subjects with DM. Changes in ankle DF ROM and stiffness in individuals with DM have been attributed to disease-dependent as well as use-dependent processes. Disease-dependent mechanisms involve non-enzymatic glycation of collagen due to the underlying metabolic disorder [11]. Use-dependent mechanisms allude to adaptive fiber shortening within the triceps surae [29]. Qualitative changes in connective tissue stiffness as well as quantitative changes related to changes in the ratio of connective tissue to contractile tissue may contribute to increased ankle stiffness in individuals with DM.

The findings of the present investigation in regards to dynamic ankle motion, stiffness and plantar loading measures agree with previous reports of dynamic ankle DF ROM [27], ankle stiffness [12] and plantar pressures, at comparable walking speeds ranging from 0.77 to 0.89 m/s. In spite of differences in passive ankle DF ROM and passive stiffness, we found that dynamic measures of ankle DF ROM, stiffness and plantar pressure did not differ between groups while walking at a similar speed, 0.89 m/s (2 mph). However, subjects with DM walked with significantly shorter stride lengths and showed trends towards lower plantar flexor moments and peak power generation compared to non-diabetic control subjects. The study and control groups did not differ in height indicating that height did not confound stride length findings. Our results are in agreement with previous reports in which shorter stride lengths were accompanied by a decrease in the forward excursion of the center of pressure [32] as well as reduced ankle moment and power [27,29]. Reduced plantar flexor moment and reduced power at push off have also been described in subjects with DM as an attempt to provide the major positive work at push-off using their hip flexors [26]. Our results suggest that subjects with DM may utilize different strategies, such as shortened stride length and reduced push-off power, compared to non-diabetic control subjects, to achieve identical functional goals, in this case, to walk at a given speed.

Contrary to our hypotheses, passive ankle DF ROM and stiffness did not predict peak DF ROM and ankle stiffness utilized during gait. While passive ankle DF ROM varied between subjects, during gait all subjects attained approximately 10° peak DF ROM (range: 5–15°). This is consistent with the findings of Riddle [33]. Analysis of ankle stiffness revealed similar findings. These results indicate that clinical measures of passive heel cord tightness and stiffness do not represent ankle motion or stiffness utilized during gait.

To evaluate the possibility that subjects alter the contribution of the biarticular gastrocnemius muscle to ankle DF ROM and stiffness through knee flexion [34], we examined peak knee flexion attained in early stance and midstance. Our data, consistent with previous reports [28], showed that subjects with DM and neuropathy utilize similar ranges of knee motion in early stance compared to non-diabetic controls. Further, associations between passive ankle measures obtained with the knee flexed (~15–20°) and gait-related measures were similar to those documented with the knee in an extended position. These findings argue against the role of limited passive DF on alterations in stance phase knee flexion as a potential mechanism [34] influencing the contribution of the biarticular gastrocnemius muscle on ankle stiffness or motion utilized during walking.

A second purpose of this study was to examine whether passive or gait-related ankle measures are associated with magnitude of plantar loading. We found that while neither passive nor dynamic DF ROM or ankle stiffness were significantly associated with plantar loading, stride length was positively associated with plantar pressure in both groups. Our findings underscore the role of stride length [35,36] as a mechanism influencing forefoot loading, even when walking velocity is controlled. We also found that longer stride lengths were accompanied by increased dynamic ankle motion and gait-related ankle stiffness in subjects with DM but not in non-diabetic controls (Table 3). Thus, our data suggest that ankle parameters are potentially linked with stride length in subjects with DM.

In summary, we found that in spite of differences in passive ankle DF ROM and stiffness, subjects with DM demonstrated gait-related ankle motion, stiffness and plantar pressures, similar to control subjects, while walking at the identical speed, 0.89 m/s (2 mph). These data indicate that clinical measures of heel cord tightness and stiffness do not represent ankle motion or stiffness utilized during gait. Our findings suggest that subjects with DM and neuropathy utilize strategies such as shortening their stride length and reducing the power of push-off to modulate plantar loading. Further studies are needed to explore the relationship between ankle flexibility and plantar loading in a wide spectrum of subjects with DM in whom ulcer formation may be problematic.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported in part by a grant from the NIH (RO1 NR07721-03).

Contributor Information

Smita Rao, Email: smita-rao@uiowa.edu.

Charles Saltzman, Email: charles-saltzman@uiowa.edu.

H. John Yack, Email: john-yack@uiowa.edu.

References

- 1.Veves A, Murray HJ, Young MJ, Boulton AJ. The risk of foot ulceration in diabetic patients with high foot pressure: a prospective study. Diabetologia. 1992;35(7):660–663. doi: 10.1007/BF00400259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiber GE, Lipsky BA, Gibbons GW. The burden of diabetic foot ulcers. Am J Surg. 1998;176(2A Suppl.):5S–10S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordois A, Scuffham P, Sheaver A, Oglesby A, Tobian JA. The health care costs of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the US. Diab Care. 2003;26(6):1790–1795. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price P. The diabetic foot: quality of life. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39 Suppl. 2:S129–S131. doi: 10.1086/383274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong DG, Stacpoole-Shea S, Nguyen H, Harkless LB. Lengthening of the Achilles tendon in diabetic patients who are at high risk for ulceration of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg. 1999;81(4):535–538. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199904000-00011. [American volume] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hastings MK, et al. Effects of a tendo-Achilles lengthening procedure on muscle function and gait characteristics in a patient with diabetes mellitus. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30(2):85–90. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2000.30.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Wunderlich RP, Tredwell J, Boulton AJ. Predictive value of foot pressure assessment as part of a population-based diabetes disease management program. Diab Care. 2003;26(4):1069–1073. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin SS, Lee TH, Wapner KL. Plantar forefoot ulceration with equinus deformity of the ankle in diabetic patients: the effect of tendo-Achilles lengthening and total contact casting. Orthopedics. 1996;19(5):465–475. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19960501-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mueller MJ, Sinacore DR, Hastings MK, Strube MJ, Johnson JE. Effect of Achilles tendon lengthening on neuropathic plantar ulcers. A randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85-A(8):1436–1445. [American volume] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Boulton AJ. Ankle equinus deformity and its relationship to high plantar pressure in a large population with diabetes mellitus. J Am Pediatr Med Assoc. 2002;92(9):479–482. doi: 10.7547/87507315-92-9-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant WP, Sullivan R, Sonenshine DE, Adam M, Slusser JH, Carson KA, et al. Electron microscopic investigation of the effects of diabetes mellitus on the Achilles tendon. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1997;36(4):272–278. doi: 10.1016/s1067-2516(97)80072-5. [discussion 330] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salsich GB, Mueller MJ. Effect of plantar flexor muscle stiffness on selected gait characteristics. Gait Posture. 2000;11(3):207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(00)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimny S, Schatz H, Pfohl M. The role of limited joint mobility in diabetic patients with an at-risk foot. Diab Care. 2004;27(4):942–946. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.4.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirtley C, Whittle MW, Jefferson RJ. Influence of walking speed on gait parameters. J Biomed Eng. 1985;7(4):282–288. doi: 10.1016/0141-5425(85)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Linden ML, Kerr AM, Hazlewood ME, Hillman SJ, Robb JE. Kinematic and kinetic gait characteristics of normal children walking at a range of clinically relevant speeds. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(6):800–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Segal A, Rohr E, Orendurff M, Shofer J, O’Brien M, Sangeorzan B. The effect of walking speed on peak plantar pressure. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25(12):926–933. doi: 10.1177/107110070402501215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warren GL, Maher RM, Higbie EJ. Temporal patterns of plantar pressures and lower-leg muscle activity during walking: effect of speed. Gait Posture. 2004;19(1):91–100. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(03)00031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burnfield JM, Few CD, Mohamed OS, Perry J. The influence of walking speed and footwear on plantar pressures in older adults. Clin Biomech. 2004;19(1):78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morag E, Cavanagh PR. Structural and functional predictors of regional peak pressures under the foot during walking. J Biomech. 1999;32(4):359–370. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mueller MJ. Identifying patients with diabetes mellitus who are at risk for lower-extremity complications: use of Semmes–Weinstein monofilaments. Phys Ther. 1996;76(1):68–71. doi: 10.1093/ptj/76.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weaver K, Price R, Czerniecki J, Sangeorzan B. Design and validation of an instrument package designed to increase the reliability of ankle range of motion measurements. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2001;38(5):471–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trevino SG, Buford WL, Jr, Nakamura T, John Wright A, Patterson RM. Use of a torque-range-of-motion device for objective differentiation of diabetic from normal feet in adults. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25(8):561–567. doi: 10.1177/107110070402500809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilken J, Saltzman C, Yack H. Reliability and validity of Iowa ankle range-of-motion device. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:A17–A18. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hicks JH. The mechanics of the foot. I. The joints. J Anat. 1953;87(4):345–357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perry J. Gait analysis: normal and pathological function. Slack Inc. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mueller MJ, Minor SD, Sahrmann SA, Schaaf JA, Strube MJ. Differences in the gait characteristics of patients with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy compared with age-matched controls. Phys Ther. 1994;74(4):299–308. doi: 10.1093/ptj/74.4.299. [discussion 309–13] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maluf KS, Mueller MJ, Strube MJ, Engsberg JR, Johnson JE. Tendon Achilles lengthening for the treatment of neuropathic ulcers causes a temporary reduction in forefoot pressure associated with changes in plantar flexor power rather than ankle motion during gait. J Biomech. 2004;37(6):897–906. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katoulis EC, Ebdon-Parry M, Lanshammar H, Vileikyte L, Kulkarni J, Boulton AJ. Gait abnormalities in diabetic neuropathy. Diab Care. 1997;20(12):1904–1907. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.12.1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mueller MJ, Minor SD, Sahrmann SA, Schaaf JA, Strube MJ. Differences in the gait characteristics of patients with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy compared with age-matched controls. Phys Ther. 1994;74(4):299–308. doi: 10.1093/ptj/74.4.299. [discussion 309–13] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu G, Siegler S, Allard P, Kirtley C, Leardini A, Rosenbaum D, et al. Standardization and Terminology Committee of the International Society of Biomechanics. ISB recommendation on definitions of joint coordinate system of various joints for the reporting of human joint motion—part I: ankle, hip, and spine. J Biomech. 2002;35(4):543–548. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis RB, DeLuca PA. Gait characterization via dynamic joint stiffness. Gait Posture. 1996;4(3):224–231. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giacomozzi C, Caselli A, Macellari V, Giurato L, Lardieri L, Uccioli L. Walking strategy in diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy. Diab Care. 2002;25(8):1451–1457. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.8.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riddle D. Foot and ankle. In: Richardson J, Iglarsh Z, editors. Orthopedic physical therapy. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1994. pp. 483–562. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orendurff M, Rohr E, Berge JS, Czerniecki J. Do plantarflexion contractures contribute to high forefoot pressures in diabetic subjects?; Annual Meeting of the Gait and Clinical Movement Analysis Society; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu H, Wertsch JJ, Harris GF, Alba HM. Walking cadence effect on plantar pressures. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76(11):1000–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)81037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown HE, Mueller MJ. A “step-to” gait decreases pressures on the forefoot. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28(3):139–145. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.3.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]