Abstract

Objectives

This study sought to test the hypothesis that activation of adenylyl cyclase 6 (AC6) expression in cardiac myocytes improves Ca2+ uptake and LV function in aging mice.

Background

Aging hearts exhibit impaired β-adrenergic receptor signaling and left ventricular (LV) dysfunction.

Methods

Twenty-month-old mice with cardiac-directed and regulated AC6 expression were randomized into two groups, and AC6 expression was activated in one group (AC6-On) but not the other (AC6-Off). One month later, LV function and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ uptake were assessed.

Results

AC6 expression was associated with increased LV contractility, as reflected by ejection fraction (P=0.02), rate of pressure development (P=0.002), and the slope of LV end-systolic pressure-volume relationship (P=0.04). No changes in LV weight to tibial length ratio, LV fibrosis, and expression of fetal genes (atrial natriuretic factor, α-skeletal muscle actin, and β-myosin heavy chain) and collagens were observed between AC6-On and AC6-Off groups. However, LV samples from AC6□On mice showed increases in: isoproterenol-stimulated cAMP production (P=0.04), PKA activity (P<0.0004), phosphorylation of phospholamban (at Ser16 site; P=0.04) and cardiac troponin I (at Ser23/24 sites; P=0.01), velocity of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ uptake (P<0.0001), and SERCA2a affinity for Ca2+ (P<0.0001). Finally, we found that AC6 expression increased sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ storage in cardiac myocytes isolated from 23-month-old rats. In contrast, AC6 expression in 7-month-old mice did not change LV function and Ca2+ uptake.

Conclusions

These results indicate that activation of cardiac AC6 expression improves impaired function of aged hearts, through improved Ca2+ uptake.

Keywords: adenylyl cyclase, cardiac aging, transgenic mouse, left ventricular function, Ca2+ uptake, extracellular matrix remodeling

Introduction

Cardiac senescence is associated with reduced left ventricular (LV) function (1–4), and impaired cardiac β-adrenergic receptor (βAR) responsiveness (5). In humans, LV diastolic and systolic function in response to βAR stimulation progressively decrease after the age of 20 years. At age 80, LV contractile reserve is less than half of what it was at age 20 (6). In addition, congestive heart failure (CHF) is a common disease of the elderly (7–9), and older patients with CHF have a particularly poor prognosis (8).

Adenylyl cyclase (AC) is the effector molecule for βAR signaling (10), playing a pivotal role in contractile responsiveness, cardiac relaxation, and LV diastolic function (11). AC catalyzes ATP to generate cAMP, a second messenger that is required for many intracellular events (12). Reduced βAR responsiveness in aging hearts occurs in the presence of increased plasma catecholamine levels (13), underscoring the abnormality in AC signaling (5,14). Indeed, impaired LV cAMP production is associated with decreased cardiac AC content in hearts from animals of advanced age (15,16). However, the precise mechanism by which AC regulates cardiac function in aging hearts is not known, and is the focus of the current investigation.

Cardiac-directed expression of AC type 6 (AC6) increases LV function in CHF (17,18), where impaired βAR-AC signaling and impaired Ca2+ uptake are prominent (19). Increased cardiac cAMP production and improved sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ uptake are of mechanistic importance for the beneficial effect of AC6 on failing hearts (18,20). In this study, we used a transgenic line with cardiac-directed tetracycline-regulated AC6 expression (21,22) to test the hypothesis that activation of cardiac AC6 expression improves LV function by increasing cardiac cAMP production and correcting Ca2+ uptake impairment in hearts from older mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The Animal Use and Care Committee of the VA San Diego Healthcare System, in accordance with NIH and AAALAC guidelines, approved this study. Twenty-month-old transgenic mice with cardiac myocyte-specific tetracycline-regulated (tet-off) AC6 expression (22) were used for echocardiography, in vivo physiology, and biochemistry studies. Suppression of AC6 transgene expression is complete until tetracycline is removed from the water supply, and chronic tetracycline treatment did not affect cardiac function. Mice were randomized into two groups. AC6 expression was activated (by removing tetracycline suppression) in one group (AC6-On), and was continuously suppressed by tetracycline in the other group (AC6-Off). These mice were studied one month after activation (or continued inactivation) of AC6 transgene expression. For comparison, echocardiography, in vivo physiology, and biochemistry studies were also performed on 7-month-old tetracycline-regulated (tet-off) AC6 mice. For Ca2+ transients study, cardiac myocytes were isolated from 23-month-old Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed under light anesthesia as previously reported (23). Data were acquired and analyzed without knowledge of group identity.

LV in vivo Physiological Studies

A 1.4F conductance-micromanometer catheter was used to measure LV pressure and volume to assess the LV end-systolic pressure-volume relationship (ESPVR) as previously reported (18). Data were acquired and analyzed without knowledge of group identity.

Necropsy and LV Fibrosis Assessment

Body and LV weights (including septum) and tibial lengths were recorded. A short axis midwall LV ring was formalin-fixed and paraffin embedded. LV sections were stained with picrosirius red, and collagen fractional area was quantified using NIH ImageJ software (24).

Biochemistry Studies

Total RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR were performed as previously reported (24). LV samples were homogenized and used for Western blotting as described previously (23). AC activity, PKA activity, caspase 3/7 activity in LV samples were measured as reported (18).

Ca2+ Uptake

LV tissues were homogenized, and ATP-dependent initial rate of SR Ca2+ uptake was measured by modified Millipore filtration technique as reported (Tang et al., 2004).

Ca2+ Transients

Cardiac myocytes were isolated from adult rats as previously described (25), plated on laminin-coated 25 mm glass coverslips, and infected with adenovirus encoding green fluorescent protein or murine AC6 (400 vp/cell). Forty hours after infection, cells were loaded with the Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent indicator Fura-2 AM (3 µM) and intracellur Ca2+ concentration was monitored using Digital Fluorescence Imaging System (Intracellular Imaging, Cincinnati, OH, USA) as described previously (23). To assess SR Ca2+ load, caffeine-induced Ca2+ release was initiated by addition of 10 mM caffeine to Tyrode's solution. The peak amplitude of Ca2+ transients was calculated from the baseline and the transient rise after caffeine treatment. Data were acquired and analyzed without knowledge of group identity.

Statistical Analysis

Results are shown as mean ± SE. Group differences were compared using unpaired, 2-tailed Student's t-test. The null hypothesis was rejected when P<0.05.

Results

AC Activity in Aging Hearts

To confirm that aging is associated with decreased AC activity in the heart (5,14,16,26), we measured LV cAMP production in 7- and 20-month-old mice. There were a 43% reduction in basal (P=0.0001), a 56% reduction in isoproterenol-stimulated (P=0.04), and a 58% reduction in NKH477-stimulated LV cAMP production (P=0.0001) in 20- vs 7-month-old mice (Fig. 1A). We also found a 59% reduction of mRNA expression of AC6, a major cardiac AC isoform, in LV samples from 20- vs 7-month-old mouse hearts (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Aging was associated with reduced LV AC activity and AC6 expression.

(A) Basal, Isoproterenol (+GTPγs), and NKH477-stimulated cAMP production were reduced in LV samples form 20-month-old vs 7-month-old mice. (B) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR showed reduced LV expression of AC6 mRNA in 20-month-old vs 7-month-old mice. Probability values (values above bars) are from Student's t-test (unpaired, 2-tailed). Error bars denote 1 SE; numbers in bars indicate group size. Iso, Isoproterenol + GTPγs; NKH, NKH477 (a water-soluble forskolin derivative)

Echocardiography

Aging was associated with a decline in LV ejection fraction (7-month-old: 80±3%, n=13; 20-month-old: 57%±10%, n=17; P<0.0001). Both 7- and 20-month-old mice with cardia□directed and regulated AC6 expression were randomized, and AC6 expression was activated in AC6-On group but not the AC6-Off group. There were no group differences (AC6-On group vs AC6-Off group) in any of the echocardiographic measures prior to activation of AC6 expression. However, in 20-month-old mice, activation of AC6 expression increased LV ejection fraction (Table 1). These mice also showed reduced LV end-systolic dimension after AC6 expression was activated (P<0.05), consistent with improved LV ejection fraction. Other measures showed no group differences. In 7-month-old mice, activation of cardiac AC6 expression did not change LV ejection fraction and any of the other echocardiographic measures (Table 1).

Table 1.

Echocardiography Measurements

| 7-month-Old | 20-month-Old | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC6-Off (7) | AC6-On (6) | P | AC6-Off (8) | AC6-On (9) | P | |

| HR (beats/min) | 597±16 | 607±14 | ns | 490±20A | 515±16A | ns |

| EDD (mm) | 3.9±0.5 | 3.6±0.6 | ns | 4.0±0.2C | 3.8±0.1C | ns |

| ESD (mm) | 2.3±0.4 | 2.0±0.3 | ns | 2.8±0.1C | 2.3±0.2C | <0.05 |

| EF (%) | 80±2 | 81±5 | ns | 59±3B | 70±4C | <0.02 |

| PWTh (mm) | 0.6±0.02 | 0.6±0.03 | ns | 0.9±0.03B | 0.9±0.02B | ns |

| IVSTh (mm) | 0.6±0.01 | 0.6±0.02 | ns | 0.9±0.04B | 0.9±0.02B | ns |

HR, heart rate; EDD, end-diastolic diameter; ESD, end-systolic diameter; EF, ejection fraction; PWTh, posterior wall thickness; IVSTh, interventricular septum wall thickness; ns, not significant;

P<0.002 vs same group at 7 months;

P<0.001 vs same group at 7 months;

not significantly different vs same group at 7 months. Transgenic mice at ages 7 and 20 months were randomized into 2 groups, respectively.

AC6 expression was activated in one group (AC6-On) but not the other (AC6-Off) for 1 month. Values represent mean ± SE. Probability values shown are from unpaired, 2-tailed Student's t-test.

LV Contractile Function

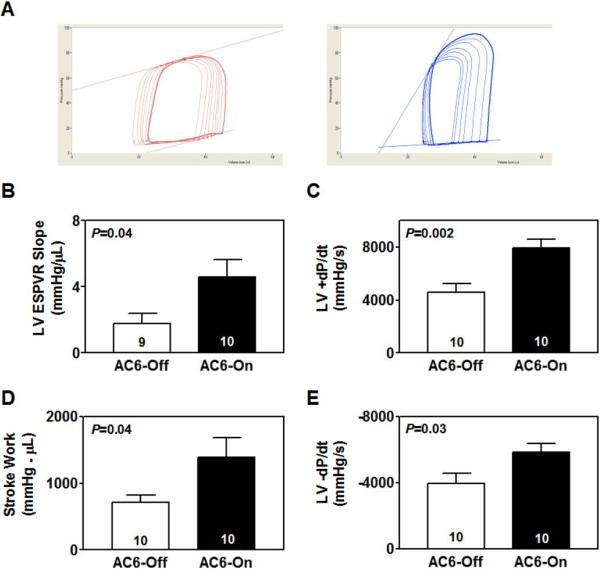

Activation of cardiac-directed AC6 expression increased the slope of ESPVR by 2.6-fold in 20-month-old mice (AC6-Off: 1.8±0.6 mmHg/μL, n=10; AC6-On: 4.6±1.0 mmHg/μL, n=9; P=0.04; Fig. 2A, B). AC6 expression in 20-month-old mice was also associated with increased rate of LV pressure development (LV +dP/dt) (P=0.002; Fig. 2C), and increased stroke work (P=0.04; Fig. 2D). There were no group differences in stroke volume (AC6-Off: 19±2 μL, n=10; AC6-On: 20±3 μL, n=10; P=0.78) and cardiac output (AC6-Off: 7±1 mL/min, n=10; AC6-On: 10±2 mL/min, n=10; P=0.20) in 20-month-old mice. Heart rate was similar in both groups (AC6-Off: 444±31 bpm, n=10; AC6-On: 469±27 bpm, n=10; P=0.55). However, in 7-month-old mice, activation of AC6 expression did not affect the slope of ESPVR (AC6-Off: 4.3±0.4 mmHg/μL, n=7; AC6-On: 4.0±0.6 mmHg/μL, n=6; P=0.69) and +dP/dt (AC6-Off: 5448±453 mmHg/s, n=7; AC6-On: 7285±1073 mmHg/s, n=6; P=0.12).

Fig. 2. Cardiac-directed AC6 expression increased LV function in 20-month-old mice.

(A) LV pressure-volume loops, generated by inferior vena caval occlusion, are shown. (B) Activation of AC6 expression increased slope of ESPVR in AC6-On mice compared to AC6-Off mice. (C) AC6-On mice showed increased +dP/dt compared with AC6-Off mice. (D) Activation of AC6 expression increased stroke work in hearts from 20-month-old mice. (E) There was a substantial increase in −dP/dt in AC6-On mouse hearts. Probability values shown are from Student's t-test (unpaired, 2-tailed). Error bars denote 1 SE; numbers in bars indicate group size.

LV Relaxation

Activation of cardiac-directed AC6 expression in 20-month-old mice decreased LV −dP/dt (P=0.03; Fig. 2E). In contrast, AC6 expression in 7-month-old mice did not affect LV −dP/dt (AC6-Off: −5260±425 mmHg/s, n=7; AC6-On: −6827±833 mmHg/s, n=6; P=0.11).

LV Hypertrophy

Activation of cardiac-directed AC6 expression in 20-month-old mice did not change LV weight to tibial length ratio (AC6-Off: 7.2±0.6 mg/mm, n=10; AC6-On: 7.5±0.5 mg/mm, n=9; P=0.71) or cross sectional cardiac myocyte area in LV sections (AC6-Off: 649±35 μm2, n=6; AC6-On: 663±21 μm2, n=6; P=0.74). AC6-Off and AC6-On mice showed similar mRNA expression of fetal genes: atrial natriuretic factor (AC6-Off: 100±22%, n=6; AC6-On: 86±15%, n=9; P=0.61), α-skeletal muscle actin (AC6-Off: 100±20%, n=6; AC6-On: 126±24%, n=9; P=0.45), and β-myosin heavy chain (AC6-Off: 100±19%, n=6; AC6-On: 84±32%, n=9; P=0.71). In addition, expression of FHL1, a regulator of LV hypertrophy, showed no group difference (AC6-Off: 100±9%, n=6; AC6-On: 113±12%, n=9; P=0.47). Similarly, activation of cardiac AC6 expression in 7-month-old mice did not change LV weight to tibial length ratio (AC6-Off: 6.4±0.4 mg/mm, n=7; AC6-On: 6.2±0.3 mg/mm, n=6; P=0.71), and mRNA expression of fetal genes and FHL1. Although activation of AC6 expression in 7-month-old mice did not change cross sectional cardiac myocyte area in LV sections (AC6-Off: 489±21 μm2, n=6; AC6-On: 465±27 μm2, n=6; P=0.50), aging was associated with an increase (7 month: 489±21 μm2, n=6; 20 months: 649±35 μm2, n=6; P=0.003).

Ca2+ Uptake

We compared ATP-dependent initial SR Ca2+ uptake in LV homogenates from 20-month-old AC6-Off and AC6-On mice. Activation of AC6 increased velocity of Ca2+ uptake in the presence of 0.2 μM and 2 μM Ca2+, approximate intracellular Ca2+ concentration range in cardiac myocytes (27) (Fig. 3A). AC6 expression also increased SERCA2a affinity for Ca2+ (Fig. 3B). Increased Ca2+ uptake and SERCA2a affinity for Ca2+ would be expected to increase cardiac contractile function as we observed. In contrast, activation of AC6 expression in 7-month-old mice did not change velocity of Ca2+ uptake (Fig. 3C) and SERCA2a affinity for Ca2+ (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3. Activation of cardiac AC6 expression increased Ca2+ uptake in 20-month-old, but not in 7-month-old mice.

(A) Cardiac-directed AC6 expression improved SR Ca2+ uptake in the presence of 0.2 and 2 μM Ca2+ in LV samples from 20-month-old mice (n=6 for each group). (B) Cardiac-directed AC6 expression increased SERCA2a affinity for Ca2+ in LV samples from 20-month-old mice. (C) AC6 expression did not affect SR Ca2+ uptake in the presence of 0.2 μM (P=0.33) and 2 μM Ca2+ (P=1.00) in LV samples from 7-month-old mice (n=6 for each group). (D) AC6 expression did not affect SERCA2a affinity for Ca2+ in LV samples from 7-month-old mice (P=0.72). Probability values are from Student's t-test (unpaired, 2-tailed). Error bars denote 1 SE; numbers in bars indicate group size.

In addition, we isolated cardiac myocytes from 23-month-old rats, infected these cells with adenovirus encoding AC6, and measured intracellular Ca2+ concentration under basal and caffeine-stimulated conditions (Fig. 4A). There was no group difference in basal intracellular Ca2+ concentration in cardiac myocytes (Fig. 4B). However, there was a 1.5-fold increase in peak amplitude of caffeine-stimulated Ca2+ transients associated with AC6 expression in cardiac myocytes from aging rats (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that AC6 expression increases Ca2+ storage in aging cardiac myocytes.

Fig. 4. Increased Ca2+ storage in cardiac myocytes from 23-month-old rats following AC6 gene transfer.

(A) Representative Ca2+ transients recorded from cardiac myocytes stimulated with caffeine. Left Panel: cardiac myocyte infected with adenovirus encoding green fluorescent protein (CON); Right Panel: cardiac myocyte infected with adenovirus encoding AC6 (AC6). (B) The bar graph shows no group difference in basal intracellular Ca2+ concentration in cardiac myocytes. Data were derived from 67 CON cells and 77 AC6 cells (blinded; P=0.40). (C) AC6 expression increased peak amplitude of caffeine-stimulated Ca2+ transients recorded from cardiac myocytes. Data were derived from 41 CON cells and 51 AC6 cells (blinded). Probability values shown are from Student's t-test (unpaired, 2-tailed). Error bars denote 1 SE.

AC6 Expression and cAMP Production

In 20-month-old mice, cardiac-directed AC6 transgene expression was associated with a 10-fold increase in LV AC6 protein content (Fig. 5A, B). LV expression of other cardiac AC isoforms (AC2, AC3, AC4, AC5, AC7, and AC9) was unchanged in these mice (Fig. 5C). Increased AC6 protein content was associated with a 1.7-fold increase in isoproterenol-stimulated cAMP production (P<0.01) and a 3-fold increase in forskolin-stimulated cAMP production (P<0.002) in LV samples from 20-month-old mice, and basal LV cAMP production was not changed (Fig. 5D). Despite unchanged protein expression of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) catalytic subunit (Fig. 5E), PKA activity was increased after activation of AC6 expression (Fig. 5F), indicating a role of AC6-increased cAMP production in regulating PKA activity in the aging heart.

Fig. 5. Cardiac-directed AC6 expression activated cAMP signaling in 20-month-old mouse hearts.

(A) Representative Western blot shows marked increase in AC6 protein content in LV samples from AC6-On mice. (B) The bar graph summarizes AC6 content in LV samples from AC6-Off and AC6-On mice. (C) AC6 expression did not affect expression of other AC isoforms in the heart. (D) AC6 expression was associated with increased LV cAMP generation capacity. NKH477, a water-soluble forskolin derivative. (E) No group difference was observed in protein content of PKA catalytic subunit (P=0.30). (F) AC6-On mice showed increased PKA activity. Probability values are from Student's t-test (unpaired, 2-tailed). Error bars denote 1 SE; numbers in bars indicate group size. du, densitometric unit

Protein Phosphorylation

We compared PKA-induced phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I (cTnI) and phospholamban (PLN) in LV homogenates from 20-month-old AC6-Off and AC6-On mice. Activation of cardiac AC6 expression in these mice was associated with 1.9–fold increase in phosphorylation of cTnI at Ser23/24 sites (P=0.01; Fig. 6A, B). No change was found in total cTnI protein content. There was also a 1.9-fold increase in phosphorylation of PLN at Ser16 site in LV sample from 20-month-old AC6-On mice compared to AC6-Off mice (P=0.04; Fig. 6A, C), although total PLN protein content was unaltered. Western blotting showed no group differences in protein content of protein phosphatase 1 [AC6-Off: 1152±195 densitometric units (du), n=6; AC6-On: 1153±277 du, n=9; P=1.00] or protein phosphatase 2A (AC6-Off: 743±104 du, n=6; AC6-On: 604±65 du, n=9; P=0.25), indicating a selective role of AC6-increased PKA activity in regulating phosphorylation of cTnI and PLN. In addition, we found no group differences in expression of sarcoplamic reticulum Ca2+ pump SERCA2a (Fig. 6D), the Ca2+ binding protein calsequestrin (Fig. 6E), or Na+-Ca2+ exchanger 1 (Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6. Cardiac-directed AC6 expression increased phosphorylation of cTnI and PLN in 20-month-old mouse hearts.

(A) Representative Western blots show marked increase in protein content of phosphor-cTnI(Ser23/24) and phosphor-PLN(Ser16) in AC6-On mouse hearts. (B)The bar graph summarizes protein content of phospho-cTnI from Western blotting. (C) The bar graph summarizes protein content of phospho-PLN from Western blotting. (D) No group difference was observed in protein content of SERCA2a (P=0.61). (E) No group difference was seen in protein content of calsequestrin (P=0.37). (F) AC6 expression did not change mRNA expression of Na+-Ca2+ exchanger 1 (P=0.27). Probability values shown are from Student's t-test. Error bars denote 1 SE; numbers in bars indicate group size. du, densitometric unit

Extracellular Matrix

Extracellular matrix remodeling, a process that involves changes of collagen synthesis, degradation, and cross-linking, leads to increased number and size of collagen fibers within interstitial spaces. There was substantial collagen deposition in LV sections from 20-month-old mice compared to 7-month-old mice (collagen fractional area: 7-month-old: 3.1±1.1%, n=7; 20-month-old: 15.4±2.5%, n=6; P<0.001); however, activation of cardiac AC6 expression did not change collagen fractional area in 20-month-old mouse hearts (AC6-Off: 15.4±2.5%, n=6; AC6-On: 14.4±2.0%, n=9; P=0.77).

We compared mRNA content of type I and III collagens, two major constituents of the cardiac extracellular matrix, in LV samples from 20-month-old AC6-Off and AC6-On mice. Activation of AC6 expression did not change mRNA expression of collagen Iα1 (AC6-Off: 100±14%, n=6; AC6-On: 129±19%, n=9; P=0.30) or IIIα1 (AC6-Off: 100±29%, n=6; AC6-On: 85±29%, n=9; P=0.73). Quantitative RT-PCR also showed that AC6 expression did not change mRNA content of matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) (AC6-Off: 100±14%, n=6; AC6-On: 135±20%, n=9; P=0.22) or MMP 8 (AC6-Off: 100±16%, n=6; AC6-On: 87±14%, n=9; P=0.55). Similar levels of periostin mRNA, a regulator of cardiac fibrosis, were seen in LV samples from 20-month-old AC6-Off and AC6-On mice (AC6-Off: 100±16%, n=6; AC6-On: 121±19%, n=9; P=0.44). There were no group differences in mRNA expression of elastin (AC6-Off: 100±10%, n=6; AC6-On: 121±18%, n=9; P=0.69) or fibronectin (AC6-Off: 100±17, n=6; AC6-On: 89±19, n=9; P=0.39).

Cardiac Myocyte Apoptosis

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) was used to evaluate apoptosis. In 20-month-old mouse hearts, AC6 expression did not change apoptosis rate (data not shown). AC6-Off and AC6-On mice showed comparable LV mRNA expression of Bcl2 (AC6-Off: 100±27%, n=6; AC6-On: 104±18%, n=9; P=0.89), an important apoptosis inhibitor. Increased AC6 expression in 20-month-old mouse hearts did not change LV caspase 3/7 activity (AC6-Off: 40.3±2.4 Unit/mg, n=6; AC6-On: 37.6±2.0 Unit/mg, n=9; P=0.41). Finally, no group difference in expression of superoxidase dismutase 2 was seen after activation of AC6 expression in 20-month-old mice (AC6-Off: 100±6%, n=6; AC6-On: 93±6%, n=9; P=0.46).

Discussion

The most important finding of this study is that activation of cardiac AC6 expression improved aging-impaired LV contractile function and relaxation. These beneficial effects were associated with increases in cAMP production, PKA activity, and phosphorylation of PLN and cTnI. Moreover, both SR Ca2+ uptake and SR Ca2+ storage in cardiac myocytes were increased following activation of AC6 expression. Improved SR Ca2+ uptake appears to be the mechanism by which AC6 expression evokes these beneficial effects.

Results from our previous studies (17,18,28,29) indicate that increased cardiac AC6 has beneficial effects in the failing heart. However, increased expression of other elements of the βAR signaling pathway (e.g. β1AR, Gαs, PKA) is associated with pronounced deleterious effects on the heart, including precipitation of heart failure, fibrosis, and increased mortality (30–33). These results indicate that AC6 is unique among βAR signaling elements in regulating cardiac function. In clinical settings, increased age is associated with reduced LV function (1–4), and elderly patients have an increased prevalence of heart failure (7–9). In this study, we tested the hypothesis that activation of AC6 expression increases function of the aging heart. We assessed LV contractile function by three different methods: LV ejection fraction, +dP/dt, and slope of ESPVR (34). Each of these measures led to the same conclusion that increased expression of cardiac AC6 improves LV contractile function in the aging heart.

Calcium plays a crucial role in controlling LV contraction and relaxation. During every heartbeat, Ca2+ is taken up and then released from SR. Aged hearts show dysfunctional SR Ca2+ uptake (35,36), which reflects reduced SR Ca2+ pump SERCA2a content (37,38) and reduced PLN phosphorylation (37–39). In the current study, we found that activation of AC6 expression increased PLN phosphorylation at Ser16 site in 20-month-old mice, while it did not change SERCA2a protein expression (Fig. 6). This change of PLN phosphorylation was associated with increased cAMP generating capacity and PKA activity. Most importantly, activation of cardiac AC6 expression increased SR Ca2+ uptake and SERCA2a affinity for Ca2+ in these 20-month-old mice (Fig. 3A, B). These results indicate that AC6 expression improves Ca2+ uptake by activating a signaling cascade leading to increased PLN phosphorylation in 20-month-old mice. Improvement of Ca2+ uptake may be of mechanistic importance for the observed increased LV function after AC6 expression (Fig. 2), given the fact that deletion of AC6 decreases Ca2+ uptake and impairs LV function (23). This notion is further supported by our findings that activation of AC6 expression did not improve SR Ca2+ uptake and SERCA2a affinity for Ca2+ in 7-month-old mouse hearts (Fig. 3C, D), where LV contractile function was unaffected.

Cardiac myocytes isolated from the hearts of 20-month-old mice may not be suitable for accurate studies for Ca2+ transient measurements. For example, despite our substantial experience in isolated cardiac myocytes from mice, we found >25% cell death rate and spontaneous beating in one-third of the viable cells. Because of these unavoidable problems, we elected to use instead cardiac myocytes isolated from elderly rats for Ca2+ transient measurements. We used rats at age of 23 months, rather than 20 months, to compensate in part for lifespan difference between mice and rats. Our data from caffeine-stimulated SR Ca2+ transient measurements provided direct evidence that AC6 expression increased SR storage. But more importantly, we showed that AC6 expression increased SR Ca2+ uptake using LV samples directly from our 20-month-old mice.

Cardiac troponin I is a sarcomeric protein directly regulating the LV function in concert with intracellular Ca2+ signals. In addition to decreased PLN phosphorylation (at Ser16 site), decreased cTnI phosphorylation (at Ser23/24 sites) is also a seminal alteration underlying impaired LV function of failing human hearts (40,41). The relative contributions of phosphorylation of cTnI vs PLN are not clear (42). Nevertheless, cTnI phosphorylation increases maximal tension development, crossbridge kinetics, and systolic power production (42,43). Expression of pseudophosphorylated cTnI at Ser23/24 sites increased LV contractility in mice (44). Moreover, improved LV function by cardiac AC6 expression is linked to increased cTnI phosphorylation at Ser23/24 sites in failing hearts (18). Importantly, cardiac aging is associated with decreased cTnI phosphorylation (45), suggesting cTnI phosphorylation is also a contributing factor for reduced LV function in aging hearts. In the present study, we showed that increased LV function was correlated with increased cTnI phosphorylation after activation of AC6 expression in aging hearts (Fig. 6). These results suggest that AC6 expression, in addition to its effects on SR Ca2+ uptake, directly regulates the property of thin filament in the contractile apparatus.

The extracellular matrix, composed mainly of fibrillar collagens (46), provides an architectural scaffold for cardiac cells and contributes to the maintenance of LV function (47,48). In this study, we confirmed that cardiac aging is associated with increased collagen deposition. However, activation of AC6 expression in 20-month-old mice did not change LV collagen deposition, indicating that the improved LV function does not likely reflect a change in LV collagen content. Additional support for this notion is our finding that AC6 expression did not change expression of type I and III collagens, the major cardiac collagen isoforms contributing 75–80% (type I) and 15–20% (type III) of total collagen content (49). Expression of MMPs and periostin was not changed by activation of AC6 expression, although aging is associated with increased expression of these important extracellular matrix proteins (50,51). In addition, our data showed that increased cardiac AC6 expression in 20-month-old mice was not associated with changes in apoptosis or reactive oxygen species. Taken together, our results suggest that activation of AC6 expression improves LV function through increased SR Ca2+ uptake.

Whether LV hypertrophy in aged mice affected our results is an important consideration. Although posterolateral and septal wall thicknesses at the mid-papillary muscle level were increased (0.3 mm) in aged mice (Table 1), echocardiographic estimate of LV mass, which considers more than a single plane, showed no difference between mice aged 20 months vs 7 months (data not shown). Cardiac myocyte cross-sectional area was increased, but the 13% increase in LV/TL ratio did not reach statistical significance. The disparity between cross sectional area and LV mass at necropsy vis-à-vis LV hypertrophy in 7 vs 20 month old mice may reflect LV hypertrophy associated with concomitant aging-related increases in cardiac myocyte apoptosis (52), or the limitations of assessing cardiac myocyte cross sectional area in hearts not obtained after diastolic arrest. Similarly, others have documented that, in aged rats, despite increased myocyte cross sectional area (52), LV mass and LV/TL were not increased (53). Our study shows that activation of cardiac AC6 expression, which had no independent effect on LV hypertrophy, improved aging-impaired LV contractile function and relaxation. Improved SR Ca2+ uptake appears to be of mechanistic importance for these beneficial effects.

Gene manipulation has recently been promoted to probe disease mechanism and test treatments designed to attenuate the progression of aging-related diseases. Transgenic lines with increased or decreased expression of a candidate gene typically are used, and, if deterioration of heart function is prevented, the candidate gene (or deletion of this gene) is said to have “rescued” the heart. However, a superior strategy, and one used in the present study, is to activate gene expression only when the adverse effect of aging is present. We accomplished this by activating AC6 expression in the setting of declining heart function in aged mice. Although additional studies will be required to determine whether activation of cardiac AC6 expression reduces mortality, our current data suggest a therapeutic potential for increased AC6 expression in aging hearts.

In conclusion, activation of cardiac-directed AC6 expression improved LV function in aged hearts. This was associated with increased cAMP production, PKA activity, and phosphorylation of PLN and cTnI. Improved SR Ca2+ uptake in cardiac myocytes appears to be of mechanistic importance for these beneficial effects.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Beginning Grants-In-Aid from the American Heart Association Western States Affiliate, NIH grants (5P01HL066941, HL088426, HL081741), and a VA Merit Review Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gerstenblith G. Echocardiographic assessment of a normal adult aging population. Circulation. 1977;56:273–278. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraticelli A, Josephson R, Danziger R, Lakatta EG, Spurgeon H. Morphological and contractile characteristics of rat cardiac myocytes from maturation to senescence. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1989;257:H259–H265. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.1.H259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiamvimonvat N. Diastolic dysfunction and the aging heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:607–610. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai DF, Santana LF, Vermulst M, et al. Overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria attenuates murine cardiac aging. Circulation. 2009;119:2789–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.822403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White M, Roden R, Minobe W, et al. Age-related changes in beta-adrenergic neuroeffector systems in the human heart. Circulation. 1994;90:1225–38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.3.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakatta EG, Sollott SJ. The “heartbreak” of older age. Mol Interv. 2002;2:431–446. doi: 10.1124/mi.2.7.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lakatta EG. Age-associated cardiovascular changes in health: Impact on cardiovascular disease in older persons. Heart Failure Rev. 2002;7:29–49. doi: 10.1023/a:1013797722156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: Major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part II: The aging heart in health: Links to heart disease. Circulation. 2003;107:346–354. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048893.62841.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marian AJ. Beta-adrenergic receptors signaling and heart failure in mice, rabbits and humans. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:11–3. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rockman HA, Koch WJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane-spanning receptors and heart function. Nature. 2002;415:206–12. doi: 10.1038/415206a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman AM. Adenylyl cyclase: A new target for heart failure therapeutics. Circulation. 2002;105:1876–1878. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000016965.24080.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsushika S, Chen L, Kawabe J, et al. Cloning and characterization of a sixth adenylyl cyclase isoform: types V and VI constitute a subgroup within the mammalian adenylyl cyclase family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:8774–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rowe JW, Troen BR. Sympathetic nervous system and aging in man. Endocr Rev. 1980;1:167–79. doi: 10.1210/edrv-1-2-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narayanan N, Tucker L. Autonomic interactions in the aging heart: age-associated decrease in muscarinic cholinergic receptor mediated inhibition of beta-adrenergic activation of adenylate cyclase. Mech Ageing Dev. 1986;34:249–59. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(86)90077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shu Y, Scarpace PJ. Forskolin binding sites and G-protein immunoreactivity in rat hearts during aging. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1994;23:188–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tobise K, Ishikawa Y, Holmer SR, et al. Changes in type VI adenylyl cyclase expression correlate with a decreased capacity for cAMP generation in the aging ventricle. Circ Res. 1994;74:596–603. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.4.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roth DM, Gao MH, Lai NC, et al. Cardiac-directed adenylyl cyclase expression improves heart function in murine cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1999;99:3099–102. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.24.3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai NC, Tang T, Gao MH, et al. Activation of cardiac adenylyl cyclase expression increases function of the failing ischemic heart in mice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1490–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mann DL, Bristow MR. Mechanisms and models in heart failure: the biomechanical model and beyond. Circulation. 2005;111:2837–49. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.500546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang T, Gao MH, Roth DM, Guo T, Hammond HK. Adenylyl cyclase type VI corrects cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium uptake defects in cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1906–12. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00356.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fishman GI. Timing is everything in life: conditional transgene expression in the cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 1998;82:837–44. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao MH, Bayat H, Roth DM, et al. Controlled expression of cardiac-directed adenylylcyclase type VI provides increased contractile function. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;56:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00539-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang T, Gao MH, Lai NC, et al. Adenylyl cyclase type 6 deletion decreases left ventricular function via impaired calcium handling. Circulation. 2008;117:61–69. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.730069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang T, Lai NC, Hammond HK, et al. Adenylyl cyclase 6 deletion reduces LV hypertrophy, dilation, dysfunciton and fibrosis in pressure-overloaded female mice. Journal of American College of Cardiology. 2010;55:1476–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang T, Lai NC, Roth DM, et al. Adenylyl cyclase type V deletion increases basal left ventricular function and reduces left ventricular contractile responsiveness to beta-adrenergic stimulation. Basic Res Cardiol. 2006;101:117–26. doi: 10.1007/s00395-005-0559-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Connor SW, Scarpace PJ, Abrass IB. Age-associated decrease of adenylate cyclase activity in rat myocardium. Mech Ageing Dev. 1981;16:91–5. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(81)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bers DM. Calcium fluxes involved in control of cardiac myocyte contraction. Circ Res. 2000;87:275–81. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.4.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai NC, Roth DM, Gao MH, et al. Intracoronary adenovirus encoding adenylyl cyclase VI increases left ventricular function in heart failure. Circulation. 2004;110:330–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136033.21777.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roth DM, Bayat H, Drumm JD, et al. Adenylyl cyclase increases survival in cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2002;105:1989–94. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014968.54967.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaussin V, Tomlinson JE, Depre C, et al. Common genomic response in different mouse models of beta-adrenergic-induced cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2003;108:2926–33. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000101922.18151.7B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antos CL, Frey N, Marx SO, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy and sudden death resulting from constitutive activation of protein kinase A. Circ Res. 2001;89:997–1004. doi: 10.1161/hh2301.100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engelhardt S, Hein L, Wiesmann F, Lohse MJ. Progressive hypertrophy and heart failure in beta1-adrenergic receptor transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7059–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.7059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwase M, Uechi M, Vatner DE, et al. Cardiomyopathy induced by cardiac Gsα overexpression. Am J Physiol. 1997:272, H585–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.1.H585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hess OM, Carroll JD. Clinical assessment of heart failure. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, editors. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 8th ed. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2008. pp. 561–581. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orchard CH, Lakatta EG. Intracellular calcium transients and developed tensions in rat heart muscle. A mechanism for the negative interval-strength relationship. J Gen Physiol. 1985;86:637–651. doi: 10.1085/jgp.86.5.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Froehlich JP, Lakatta EG, Beard E, Spurgeon HA, Weisfeldt ML, Gerstenblith G. Studies of sarcoplasmic reticulum function and contraction duration in young and aged rat myocardium. J Mol Coll Cardiol. 1978;10:427–438. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(78)90364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taffet GE, Tate CA. CaATPase content is lower in cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum isolated from old rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1993;264:H1609–H1614. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.5.H1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu A, Narayanan N. Effects of aging on sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-cycling proteins and their phosphorylation in rat myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;275:H2087–H2094. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.6.H2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang MT, Narayanan N. Effects of aging on phospholamban phosphorylation and calcium transport in rat cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Mech Ageing Dev. 1990;54:87–101. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(90)90018-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Messer AE, Jacques AM, Marston SB. Troponin phosphorylation and regulatory function in human heart muscle: Dephosphorylation of Ser23/24 on troponin I could account for the contractile defect in end-stage heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:247–259. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacLennan DH, Kranias EG. Phospholamban: A crucial regulator of cardiac contractility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:566–577. doi: 10.1038/nrm1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Metzger JM, Westfall MV. Covalent and noncovalent modification of thin filament action: the essential role of troponin in cardiac muscle regulation. Circ Res. 2004;94:146–58. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000110083.17024.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solaro RJ. Modulation of cardiac myofilament activity by protein phosphorylation. In: Fozzarad H, Solaro RJ, editors. Handbook of Physiology, Volume 1, The Heart. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. pp. 264–300. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takimoto E, Soergel DG, Janssen PM, Stull LB, Kass DA, Murphy AM. Frequency- and afterload-dependent cardiac modulation in vivo by troponin I with constitutively active protein kinase A phosphorylation sites. Circ Res. 2004;94:496–504. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000117307.57798.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maejima Y, Adachi S, Ito H, Hirao K, Isobe M. Induction of premature senescence in cardiomyocytes by doxorubicin as a novel mechanism of myocardial damage. Aging Cell. 2008;7:125–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jugdutt BI. Extracellular matrix and cardiac remodeling. In: Villarreal F, editor. Interstitial Fibrosis in Heart Failure. Springer; 2004. pp. 23–55. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindsey ML, Borg TK. Understanding the role of the extracellular matrix in cardiovascular development and disease: Where do we go from here? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:349–63. doi: 10.1038/nrm809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Legrice I, Pope A, Smaill B. The architecture of the heart: Myocyte organization and the cardiac extracellular matrix. In: Villarreal F, editor. Interstitial Fibrosis in Heart Failure. Springer; 2004. pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindsey ML, Goshorn DK, Squires CE, et al. Age-dependent changes in myocardial matrix metalloproteinase/tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase profiles and fibroblast function. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:410–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Borg TK, Markwald R. Periostin: more than just an adhesion molecule. Circ Res. 2007;101:230–1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.159103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anversa P, Hiler B, Ricci R, Guideri G, Olivetti G. Myocyte cell loss and myocyte hypertrophy in the aging rat heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1441–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raya TE, Gaballa M, Anderson P, Goldman S. Left ventricular function and remodeling after myocardial infarction in aging rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1997;273:H2652–H2658. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.6.H2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]