Abstract

Introduction

Serum proteomics and mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and KRAS have been associated with benefit after therapy with EGFR-targeted therapies in non-small cell lung cancer, but all three have not been evaluated in any one study.

Hypothesis

Pretreatment serum proteomics predicts survival in Western advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients with wild-type EGFR and independent of KRAS mutation status.

Methods

We analyzed available biospecimens from Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 3503, a single-arm phase II study of erlotinib in first-line advanced lung cancer, for proteomics signatures in the previously described serum matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization proteomic classifier (VeriStrat) as well as for KRAS and EGFR mutations.

Results

Out of 137 enrolled patients, analyzable biologic samples were available on 102. Nine of 41 (22%) demonstrated KRAS mutations and 3 of 41 (7%) harbored EGFR mutations. VeriStrat classification identified 64 of 88 (73%) as predicted to have “good” and 24 of 88 (27%) predicted to have “poor” outcomes. A statistically significant correlation of VeriStrat status (p < 0.001) was found with survival. EGFR mutations, but not KRAS mutations, also correlated with survival.

Conclusions

The previously defined matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization predictor remains a potent and highly clinically significant predictor of survival after first-line treatment with erlotinib in patients with wild-type EGFR and independent of mutations in KRAS.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Proteomics, Erlotinib, KRAS, EGFR

One of the most significant advancements in lung cancer therapy over the last decade has been the introduction of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeted therapies. The efficacy of small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), erlotinib and gefitinib, and antibodies, cetuximab and panitumumab, have been examined in clinical trials as first-, second-, and later-line agents, alone or in combination with standard cytotoxic chemotherapeutics.1–8 Significant survival benefits have been seen for small molecule EGFR-TKIs in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in these trials, despite low objective response rates (RRs). Importantly, in the randomized clinical trial BR.21, erlotinib showed an increased overall survival (OS) in NSCLC over placebo,3 and in the IRESSA non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Trial Evaluating REsponse and Survival against Taxotere (INTEREST) trial, it showed equivalence to second-line chemotherapy,9 both in unselected patients.

Molecular characterization of tumors from clinical trials has provided important information regarding potential biomarkers and their correlation with response to small molecule inhibitors. These retrospective analyses of patient samples from clinical trials have shown that EGFR-activating mutations are very highly correlated with RR and with OS and time to progression (TTP) regardless of therapy.10–15 Another genetic factor that has been reported to predict better RR and OS is high polysomy/amplification for the EGFR locus.16 However, EGFR protein expression, as determined by immunohistochemistry, is only marginally predictive if at all.17,18 The presence of a mutation in the KRAS gene has been associated with a lack of response to EGFR inhibition therapy and is used by many groups to select patients against therapy with EGFR-targeted agents. This is especially true in the treatment of colorectal cancer (CRC) with the monoclonal antibodies cetuximab and panitumumab.19–21 Several retrospective studies in NSCLC have reported similar results with regard to response to small molecule TKIs and KRAS status, as reviewed in Ref. 21. Although most of these biomarkers predict response, their predictive value for survival is much less clear. In addition, all the above tests are assayed on tumor biopsy material, which is not only difficult to get in a large fraction of cases but also highly prone to artifacts related to the heterogeneity within a tumor and between primary tumor sites and metastases.22–24

In a recent article, we have shown that a classifier based on matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry of pretreatment serum can predict outcome of patients taking erlotinib or gefitinib.25 Our analysis is based on a fixed and reproducible assay that examines eight protein peaks in spectra that are derived from 1 μl of serum or plasma. Although the identity of most of these peaks is known, they seem to have posttranslational modifications that are still under investigation (data not shown). To assess the value of our predictor in the context of the EGFR and KRAS mutation status of the tumor, we have analyzed these mutations in the cooperative group study E3503. Using updated clinical data, we again confirmed the prognostic value of VeriStrat and EGFR mutations in both TTP and OS in this single-arm study. KRAS mutations, however, lacked any association with either.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Selection of Patients and Treatment

The eligibility criteria for Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 3503 were for patients with confirmed advanced (stage IIIB with pleural effusion or stage IV or recurrent disease) NSCLC, with no history of prior chemotherapy or targeted therapy for metastatic disease and good organ function, with a performance status of 0 to 2. Patients were enrolled from September 2004 to August 2005 and treatment consisted of erlotinib, 150 mg/d with clinical evaluations every 4 weeks, and was continued until progressive disease, unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal. Tumor measurements were made every 8 weeks.

Tumor Samples and DNA Isolation

Tumor tissue was obtained from ECOG as formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue in 10-μM-thick sections on glass slides. The percentage tumor and areas of highest tumor content were identified in hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides and marked by a trained pathologist specializing in classification of lung tumors. The corresponding areas were marked on unstained slides containing adjacent sections and microdissected from the tumor tissue using a scalpel blade. DNA was isolated from the tumor tissue by placing the scrapings from the slide directly into a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube containing 50 μl of a solution of 25 mM sodium hydroxide and 0.2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. The tube was placed into a heating block at 95°C for 20 minutes with occasional vortexing. Neutralization was performed by removing the tube from the heat and adding an equal volume of 40 mM Tris hydrochloric acid. The tube was micro-centrifuged for 5 minutes at maximum speed to pellet undigested material and 2 to 4 μl of sample removed for polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

PCR for EGFR Exons 19 and 21 and for KRAS Exon 2

PCR products were generated using the following primers: exon 19 outside primers Exon19F (5′-CCAGATCACTGGGCAGCATGTGGCACC-3′) and Exon19R (5′-AGCAGGGTCTAGAGCAGAGCAGCTGCC-3′) and inside primers Exon19intF (5′-CCATCTCACAATTGCCAGTTA-3′) and Exon19intR (5′-TGCCAGACATGAGAAAAGGTG-3′). For exon 21, outside primers Exon21F (5′-CTAACGTTCGCCAGCCATAAGTCC-3′) and Exon21R (5′-GCTGCGAGCTCACCCAGAATGTCTGG-3′) and inside primers Exon21intF (5′-CAGCCATAAGTCCTCGACGTGG-3′) and Exon21intR (5′-CATCCTCCCCTGCATGTGTTAAAC-3′) were used. KRAS primers included the outside primers KrasF (5′-GTACTGGTGGAGTATTTGAT-3′) and KrasR (5′-TGAAAATGGTCAGAGAAACC-3′) and the internal primers KrasintF (5′-GTATTAACCTTATGTGTGACA-3′) and KrasintR (5′-GTCCTGCACCAGTAATATGC-3). Conditions for the EGFR exon 19 and 21 reactions were 95°C (5 minutes) followed by 30 rounds of 95°C (45 seconds), 60°C (45 seconds), and 72°C (45 seconds) and 1 round of 72°C (10 minutes). KRAS PCR conditions were the same except for the annealing temperature, which was 52°C. PCR products were purified with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and sequenced directly with the internal PCR primers by submitting purified samples to GenePass, Inc. (Nashville, TN).

Proteomic Analysis

The preparation of the serum samples for proteomic analysis and description of the VeriStrat predictor are reported in Ref. 25.

Statistical Analysis

This analysis was based on ECOG 3503 data pulled on April 27, 2009. Response was evaluated using RECIST criteria. The objective RR was defined as the proportion of patients with either a complete response or a partial response among all analyzable patients. Patients who were unevaluable or unknown for response were included in the denominator when computing this rate. The disease control rate was defined similarly as the objective RR except patients with stable disease (SD) were included in the numerator rather than in the denominator. OS was defined as the time from registration to death from any cause. Patients who were alive at the time of this analysis were censored at the date last known alive. TTP was defined as the time from registration to first documentation of disease progression (per RECIST). Patients without documented progression were censored at the time of last known free of progression.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize patient demographics and disease characteristics. Exact binomial 90% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed for the objective RR. The difference in RR or disease control rate between EGFR/KRAS mutation status was examined by Fisher’s exact test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for event-time distributions. The OS and TTP curves between groups were compared using log-rank tests. The association of biomarkers with survival was evaluated in univariate analyses and multivariate analyses using Cox proportional hazards regression modeling. All p values are two-sided. Model building techniques were used in four steps relying first on univariate testing for each biomarker. Biomarkers with statistical significance <0.2 were considered for the next step of model building. Backward elimination, forward selection, and stepwise selection (with p < 0.2) were then performed on biomarkers to select possible models. At the final stepwise step, two-way interactions under the hierarchical principle were added into the model as well for considerations. The proportional hazards assumption of each covariate was evaluated after model building using time-by-covariate interactions. Model fitting was assessed via the Cox-Snell generalized residuals plot and diagnostics for influential points. A level of 5% was considered statistically significant unless specified otherwise.

RESULTS

Patient Population

Of the 137 patients enrolled in ECOG 3503, 102 patients (excluding those with definitely ineligible status) had analyzable biologic samples (Table 1). Table 2 shows the demographics and disease characteristics of these 102 patients. The median age was 70 years with a range of 41 to 93 years. The majority of the patients were women (57.8%) and whites (92.2%), with African American and Asian comprising 5.9% and 2.0%, respectively. Most of the patients entering the study were stage IV, not recurrent (70.6%) with multiple metastatic sites. Most (94.1%) had not received any prior chemotherapies for recurrent or metastatic disease. Six of the 102 had previous adjuvant chemotherapy.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of Proteomics and Mutation Data

| N (Out of 137 Enrolled Patients) | N (Out of 102 Analyzable Patients) | |

|---|---|---|

| Veristrat results | ||

| Missing | 44 | 14 |

| Poor | 25 | 24 |

| Good | 68 | 64 |

| Exon 19 | ||

| Missing | 94 | 61 |

| Wild type | 43 | 41 |

| Exon 21 | ||

| Missing | 94 | 61 |

| Mutation | 3 | 3 |

| Wild type | 40 | 38 |

| KRAS | ||

| Missing | 94 | 61 |

| GTT (12) | 1 | 1 |

| TGC (13) | 2 | 2 |

| TGT (12) | 7 | 6 |

| Wild type | 33 | 32 |

| Tumor (%) | ||

| Missing | 94 | 61 |

| 30 | 4 | 4 |

| 40 | 4 | 4 |

| 50 | 4 | 4 |

| 60 | 8 | 8 |

| 70 | 5 | 4 |

| 80 | 5 | 5 |

| 85 | 2 | 2 |

| 90 | 9 | 8 |

| 95 | 1 | 1 |

| 100 | 1 | 1 |

TABLE 2.

Patients Demographics and Disease Characteristics

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 43 (42.2) |

| Female | 59 (57.8) |

| Race | |

| White | 94 (92.2) |

| Black | 6 (5.9) |

| Asian | 2 (2.0) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Unknown | 4 (3.9) |

| Non-Hispanic | 97 (95.1) |

| Institution refusal | 1 (1.0) |

| Performance status | |

| 0 | 29 (28.4) |

| 1 | 47 (46.1) |

| 2 | 26 (25.5) |

| Weight loss in previous 6 mo (%) | |

| <5 | 69 (67.6) |

| 5–<10 | 16 (15.7) |

| 10–<20 | 14 (13.7) |

| ≥20 | 3 (2.9) |

| Disease stage at entry | |

| IIIB (not recurrent) | 8 (7.8) |

| IV (not recurrent) | 72 (70.6) |

| Recurrent | 22 (21.6) |

| Histology | |

| Squamous carcinoma | 11 (10.8) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 66 (64.7) |

| Large-cell carcinoma | 1 (1.0) |

| Bronchoalveolar carcinoma | 2 (2.0) |

| Non-small cell lung cancer, NOS | 17 (16.7) |

| Combined/mixed | 2 (2.0) |

| Other | 3 (2.9) |

| Pleural effusion present | |

| No | 63 (61.8) |

| Yes, clinical assessment only | 22 (21.6) |

| Yes, but cytologically negative | 1 (1.0) |

| Yes, cytologically malignant | 16 (15.7) |

| Metastatic sites | |

| No metastatic sites | 1 (1.0) |

| Single site | 11 (10.8) |

| Multiple sites | 90 (88.2) |

| Prior chemotherapy | 6 (5.9) |

| Prior hormonal therapy | 1 (1.0) |

| Prior radiation therapy | 22 (21.6) |

| Prior surgery | 33 (32.4) |

| Other prior therapy | |

| Missing | 6 (5.9) |

| Single other prior therapy | 1 (1.0) |

| Not applicable (no therapy) | 95 (93.1) |

| Age | |

| Median (range) | 70 (41–93) |

NOS, not otherwise specified.

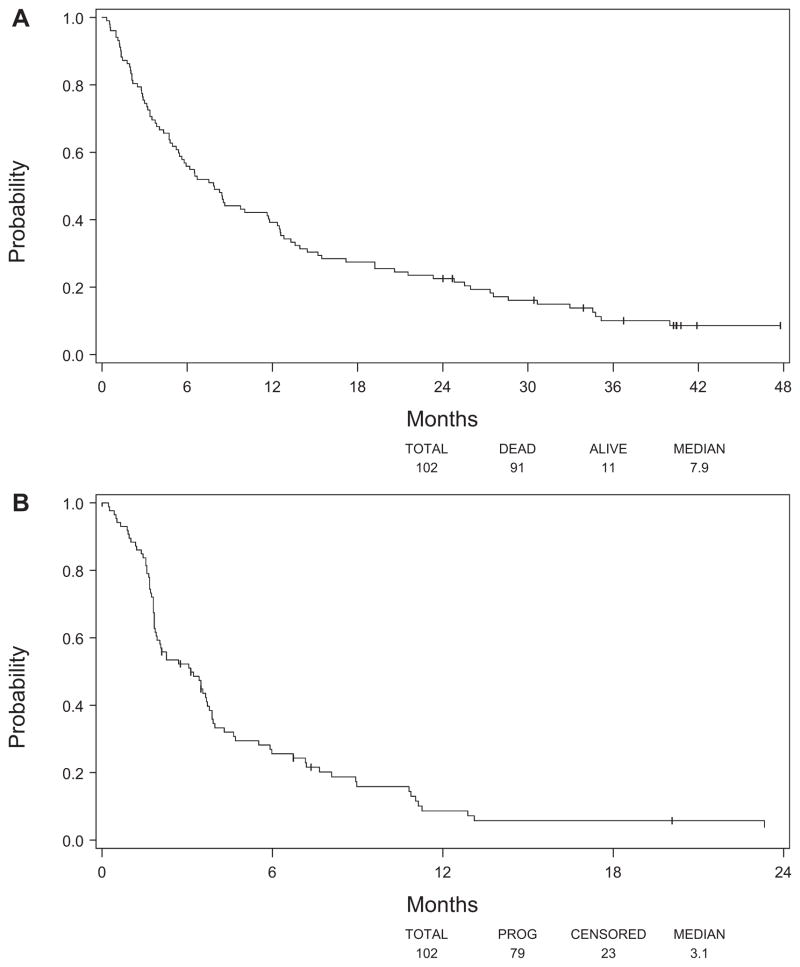

Basic Overall Clinical Outcomes

The median OS by all analyzable patients (102) was 7.9 months (95% CI: 5.5–11.7 months) (Figure 1A), whereas the median TTP for these patients was 3.1 months (95% CI: 1.9–3.8 months) (Figure 1B). Seven of these patients had an objective response (two complete responses and five partial responses) (6.9%; 90% CI: 3.3–12.5%), 32 had SD (31.4%), and 39 progressed (38.2%) as the best overall response. For the remaining 24 patients, the response was either unknown (n = 3) or unevaluable (n = 21).

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis showing (A) overall survival and (B) time to progression for all analyzable patients.

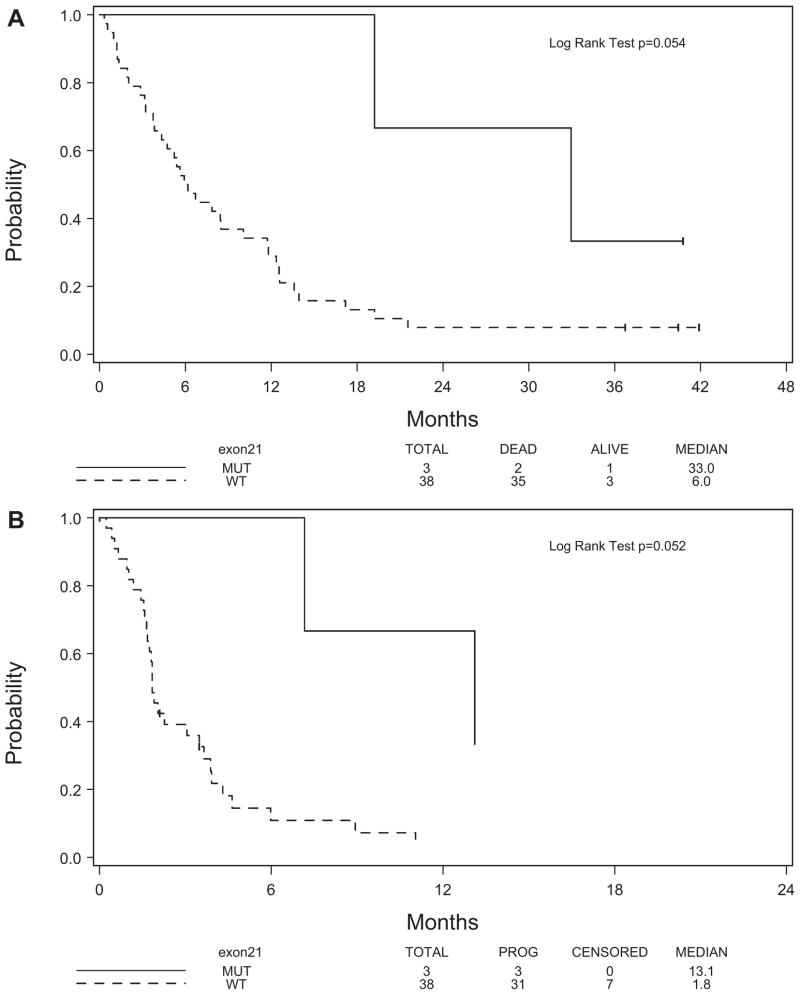

EGFR Mutation Status

Seventy-one tumor samples were obtained from ECOG 3503 enrolled patients in the form of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections on glass slides. Using adjacent hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections, the areas containing tumor were marked and the percentage of tumor determined. Of those 71 slides, there were 23 that contained too little tumor to be analyzed. For our analysis, we focused our attention on EGFR exons 19 and 21 as these two exons comprise the majority, approximately 90%, of the known mutations in EGFR.13 Of the 48 slides for which DNA was isolated, PCR products for either exon 19 or 21 could not be obtained for five samples, even after multiple attempts. Among the 43 tumor samples for which PCR products were obtained (Table 1), we found no exon 19 mutations, but we did find three exon 21 mutations (7%).

Response data was available on 41 analyzable patients for whom EGFR mutation status was determined (Table 1). Of these, the three patients with EGFR mutation fell into the SD category (Table 3). Though no difference in objective RR was observed between patients with mutant EGFR and wild-type EGFR (0.00 versus 0.03, respectively), a significant difference in disease control rate was observed (1.00 versus 0.34, p = 0.05). Although the median OS of these patients was better than the median of those patients with wild-type EGFR (33.0 versus 6.0 months), the increase in OS was nearly statistically significant with a p value of 0.054 due to the small sample size (Figure 2A). The TTP of these three patients was also better than the patients with wild-type EGFR (13.1 versus 1.8 months, p = 0.052) (Figure 2B).

TABLE 3.

Overall Response by Exon 21

| Best Overall Response | Exon 21 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation, N | Wild Type, N | Total, N | |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | |

| Partial response | 1 | 1 | |

| Stable disease | 3 | 12 | 15 |

| Progression | 19 | 19 | |

| Unevaluable | 5 | 5 | |

| Total | 3 | 38 | 41 |

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis showing (A) overall survival and (B) time to progression by exon 21 mutation.

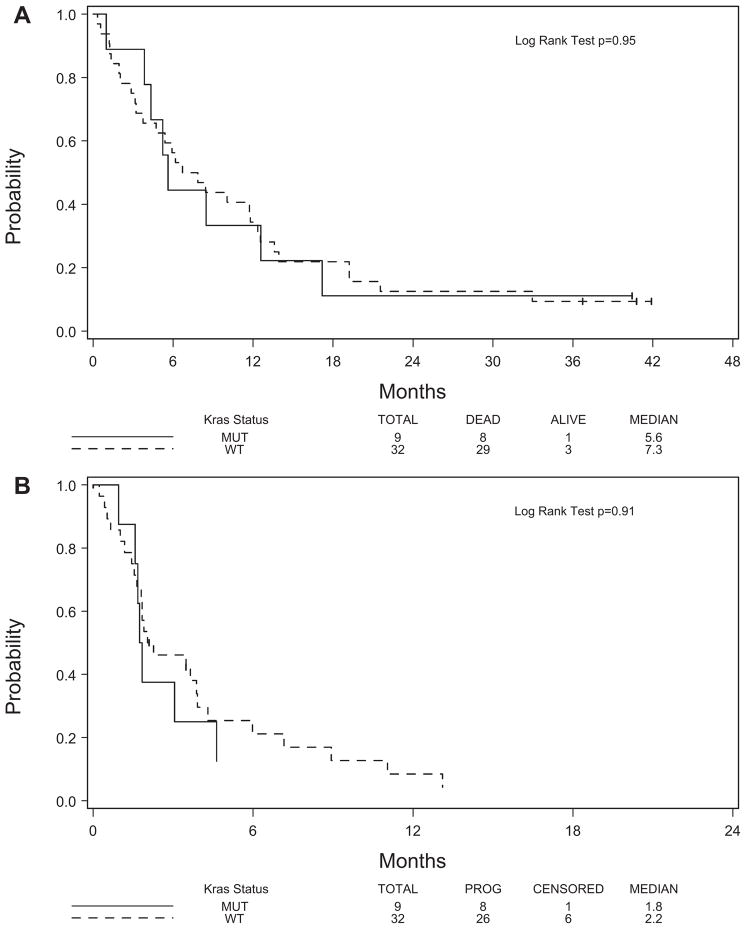

KRAS Mutation Status

Of the 41 analyzable patients for whom KRAS exon 2 mutation status was performed, nine mutations were found (22%), which agrees with what has been reported previously in the literature for NSCLC (Table 1). Three of these patients had stable disease, five patients had progressive disease, and one patient was unevaluable for best overall response (Table 4). No difference in objective RR was found between patients with mutant KRAS and wild-type KRAS nor was there any difference in the disease control rate between the two groups. The Kaplan-Meier plots of OS and TTP indicate that there is no correlation of these clinical parameters with the KRAS status of the tumor (Figures 3A, B).

TABLE 4.

Overall Response by KRAS

| Best Overall Response |

KRAS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTT (12), N | TGC (13), N | TGT (12), N | Wild Type, N | Total, N | |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | |||

| Partial response | 1 | 1 | |||

| Stable disease | 3 | 12 | 15 | ||

| Progression | 1 | 1 | 3 | 14 | 19 |

| Unevaluable | 1 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Total | 1 | 2 | 6 | 32 | 41 |

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis showing (A) overall survival and (B) time to progression by KRAS mutation.

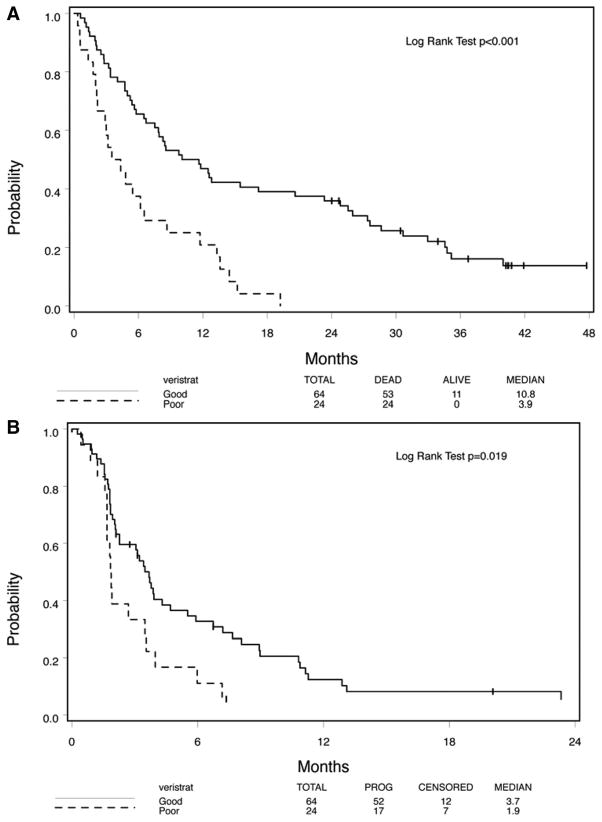

VeriStrat Classification

Of 88 patients (out of 102 analyzable patients) with VeriStrat results, 64 were classified as VeriStrat “good” and 24 were “poor.” Patients with “good” VeriStrat score are expected to have a better OS or TTP than their counterparts. Using updated OS and TTP from that reported previously,25 highly statistically significant differences between the two groups were maintained (Figures 4A,B; p < 0.001 and p = 0.019, respectively).

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan-Meier analysis showing (A) overall survival and (B) time to progression as determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI).

Serum was available for all three patients whose tumors contained EGFR mutations. Two (67%) were identified as VeriStrat “good” and one (33%) was identified as VeriStrat “poor.” In contrast, serum was available for 24 of 38 patients with wild-type EGFR. Seventeen (71%) were identified as VeriStrat “good” and seven (29%) were identified as VeriStrat “poor.”

Of the six sera available from patients with KRAS mutant tumors, VeriStrat predicted that five (83%) belonged in the “good” group, whereas only one (17%) was assigned to the “poor” group. The median OS and TTP of the five patients assigned to the “good” group were 12.6 months (95% CI: 5.2–∞ months) and 1.7 months (95% CI: 1.0–31.5 months), respectively. The one patient assigned to the poor group had an OS of 4.3 months and a TTP of 1.7 months. Of the 21 (out of 32) patients with wild-type KRAS who also had serum data available, 14 (67%) were in the “good” group and 7 (33%) were assigned to the “poor” group. EGFR and KRAS mutations did not correlate with VeriStrat status, but the power of this observation for EGFR mutations is limited by the small number in the analyzed sample set.

Table 5 presents results from univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis with VeriStrat results, EGFR mutation status, and KRAS mutation status as explanatory variables for OS and TTP, separately or jointly. For OS, as suggested by the univariate models, a patient with VeriStrat results = good has a risk of death that is 0.36 times that of a patient whose VeriStrat results = poor (p = 0.001) and a patient with EGFR mutation has a risk that is 0.27 times that of a patient with a wild-type EGFR (p = 0.07). No difference in hazard of death exists between patients with KRAS mutation and those without KRAS mutation. The multivariate model indicates that both EGFR status and VeriStrat results nearly achieve statistical significance in predicting OS. Based on this model, a patient with VeriStrat results = good has a risk that is 0.44 times that of a patient whose VeriStrat results = poor (p = 0.07) while holding EGFR mutation status constant. In addition, a patient with EGFR mutation has a risk that is 0.26 times that of a patient with a wild-type EGFR (p = 0.08) while holding VeriStrat results constant. For TTP, as suggested by the univariate models, a patient with VeriStrat results = good has about half risk of a patient whose VeriStrat results = poor (p = 0.02) and a patient with EGFR mutation has a risk that is about one-third of a patient with a wild-type EGFR (p = 0.06). No difference in hazard of progression was observed between patients with KRAS mutation and those without KRAS mutation. No multivariate model was successfully fitted for TTP.

TABLE 5.

Outcomes from Univariate and Multivariate Models on Overall Survival and Time to Progression

| Model | n | Predictor(s) | OS |

TTP |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Univariate model | 88 | VeriStrat | 0.36 | 0.21–0.60 | 0.001 | 0.51 | 0.28–0.90 | 0.02 |

| 41 | EGFR | 0.27 | 0.06–1.13 | 0.07 | 0.31 | 0.09–1.06 | 0.06 | |

| 41 | KRAS | 1.02 | 0.47–2.24 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.41–2.23 | 0.92 | |

| Multivariate model | 27 | EGFR | 0.26 | 0.06–1.16 | 0.08 | |||

| VeriStrat | 0.44 | 0.18–1.08 | 0.07 | |||||

OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; TTP, time to progression; CI, confidence interval; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

All these results imply that both EGFR mutation status and VeriStrat are predictors for OS and TTP, and that KRAS is not useful.

DISCUSSION

In the past, treatment decisions for patients were based on the tumor’s organ of origin and light microscopic appearance. With the discovery and increasing understanding of the importance of patterns of genetic abnormalities in tumors, and the development of agents designed to target the deregulated pathways resulting from these lesions, a polar opposite thinking began to emerge. That is, all therapeutic decisions should be driven by an understanding of these acquired lesions, and their organ context was irrelevant. In this study, we provide evidence that a middle path may in fact be the best, and the impact of these lesions may be highly dependent on tissue context.

Molecular analyses of multiple large clinical trials for NSCLC and CRC using EGFR inhibitors have made it clear that molecular features are important in predicting response to EGFR inhibition therapy. In CRC, for example, patients positive for EGFR protein expression are routinely being treated with cetuximab or panitumumab as a single agent or in combination with standard cytotoxic therapies,26 and these agents have shown activity in NSCLC as well.27 In colon cancer, analysis of several large trials has determined that clinical benefit from the regimen was highly dependent on having a wild-type KRAS gene.19–21,28 In fact, in one randomized phase III study looking at the addition of cetuximab to a regimen of bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine for CRC, analysis of tumors showed that the presence of a KRAS mutation was associated with decreased TTP and worse quality of life with these agents.29 These data were so powerful that it is now widely accepted that testing for this mutation is essential before prescribing these therapies.

In NSCLC, there are many studies showing activity of EGFR-targeted therapies. Unlike CRC, however, a relatively high percentage of NSCLC tumors contain mutations in EGFR.10–12 Tumors with these mutations typically occur in never smokers or light smokers and are more common in Asian patients and women. Tumors with a mutant EGFR have very high RRs to TKIs, leading to the initiation of prospective trials selecting patients for erlotinib therapy based on the presence of an EGFR mutation.30–32 CRC and NSCLC tumors both harbor frequent KRAS mutations, and there are data that NSCLC tumors with mutant KRAS do not respond to erlotinib or gefitinib therapy and, based on this and the data in CRC, screening for mutations in KRAS has been proposed for selection of patients who should not receive therapy with EGFR-targeted therapies.14–16,21,28,33–35

Other molecular features are being proposed for the selection of patients for therapy with these inhibitors. In a previous study, we developed a classification algorithm based on matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-generated protein peaks from pretreatment serum or plasma that would allow identification of patients with a higher likelihood of survival benefit from erlotinib or gefitinib therapy.25 One of the validation cohorts previously reported for this classifier was from the multicenter cooperative group trial of erlotinib as first-line therapy in advanced NSCLC.25 This classifier has been commercialized with the trade name of VeriStrat, and this classification was found to be independent of clinical features, such as smoking, sex, and histology, that are usually associated with response to the EGFR-TKIs. In addition, the algorithm was predictive and not just prognostic, as it did not classify patients for good or poor outcomes when treated with standard chemotherapy or surgery alone but it did for patients treated with erlotinib or gefitinib. However, it is possible that this classifier was simply identifying patients with KRAS mutant tumors, and in light of the CRC data, we felt it was important to answer this question.

In this study, we used significantly updated clinical data from E3503 to reanalyze the survival association of classification of these patients using VeriStrat and analyzed all the available tumor samples for EGFR and KRAS mutations. Of the available tumor samples, we found three EGFR mutations (~7%) and nine KRAS mutations (~22%). These frequencies of EGFR and KRAS mutations agree with other studies in NSCLC. Our results showed that for VeriStrat, the survival prediction using updated clinical data was even better than reported previously, and as expected, that survival and TTP were also associated with EGFR mutations. KRAS status, however, showed no correlation with outcome.

We then evaluated how the classifier results correlated with EGFR and KRAS mutation status. Of the available tumor samples for which VeriStrat results and mutation status were known, two of the three EGFR mutant tumors were classified as good and one classified as poor, and five of the six patients with a KRAS mutation and serum available were classified as VeriStrat “good.” These results, and the KRAS survival data, suggest that the prediction made by the algorithm is independent of EGFR and KRAS status, although the confidence of this conclusion for EGFR mutations is limited by the small number of mutations in this cohort. We look forward to confirmation of these findings when the KRAS analysis of several large studies evaluating cetuximab in lung cancer (e.g., BMS 099, FLEX, and SWOG 0342) are published. Preliminary data presented in abstract form support our conclusions. Thus, there may be a subset of NSCLC patients with KRAS mutations who will benefit from EGFR-TKI therapy and VeriStrat may be capable of identifying those patients with potential for a better outcome.

In this study, we show data that identical mutations in tumors from different organs might have different implications for therapy, supporting the concept of organ-specific trial designs, as opposed to mutation-specific designs. In addition, these data suggest that it is reasonable to consider VeriStrat “good” NSCLC patients whose tumors have wild-type EGFR or KRAS mutations for EGFR-targeted therapies.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from U01 CA114771-03, P50 CA90949, BioDesix, and ECOG, NCI Grant CA23318.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Lee has served as a consultant to Genentech and Dr. Carbone has served as an unpaid consultant to BioDesix.

References

- 1.Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 Trial) (corrected) J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2237–2246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong T, Morgensztern D, Govindan R. EGFR inhibitors as first-line therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:303–310. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181645477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herbst RS, Prager D, Hermann R, et al. TRIBUTE: a phase III trial of erlotinib hydrochloride (OSI-774) combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5892–5899. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giaccone G, Herbst RS, Manegold C, et al. Gefitinib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial—INTACT 1. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:777–784. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Socinski MA. Antibodies to the epidermal growth factor receptor in non small cell lung cancer: current status of matuzumab and panitumumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:s4597–s4601. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Socinski MA, Saleh MN, Trent DF, et al. A randomized, phase II trial of two dose schedules of carboplatin/paclitaxel/cetuximab in stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1068–1073. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim ES, Hirsh V, Mok T, et al. Gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (INTEREST): a randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1809–1818. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13306–13311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405220101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riely GJ, Pao W, Pham D, et al. Clinical course of patients with non-small cell lung cancer and epidermal growth factor receptor exon 19 and exon 21 mutations treated with gefitinib or erlotinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:839–844. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller VA, Riely GJ, Zakowski MF, et al. Molecular characteristics of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma subtype, predict response to erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1472–1478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider CP, Heigener D, Schottvon-Romer K, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor-related tumor markers and clinical outcomes with erlotinib in non-small cell lung cancer: an analysis of patients from german centers in the TRUST study. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:1446–1453. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31818ddcaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu CQ, da Cunha Santos G, Ding K, et al. Role of KRAS and EGFR as biomarkers of response to erlotinib in National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR.21. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4268–4275. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cappuzzo F, Gregorc V, Rossi E, et al. Gefitinib in pretreated non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): analysis of efficacy and correlation with HER2 and epidermal growth factor receptor expression in locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2658–2663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark GM, Zborowski DM, Santabarbara P, et al. Smoking history and epidermal growth factor receptor expression as predictors of survival benefit from erlotinib for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer in the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group study BR.21. Clin Lung Cancer. 2006;7:389–394. doi: 10.3816/clc.2006.n.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M, et al. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1626–1634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.7116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1757–1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raponi M, Winkler H, Dracopoli NC. KRAS mutations predict response to EGFR inhibitors. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bozzetti C, Tiseo M, Lagrasta C, et al. Comparison between epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene expression in primary non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and in fine-needle aspirates from distant metastatic sites. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:18–22. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31815e8ba2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gow CH, Chang YL, Hsu YC, et al. Comparison of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations between primary and corresponding metastatic tumors in tyrosine kinase inhibitor-naive non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:696–702. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Italiano A, Vandenbos FB, Otto J, et al. Comparison of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene and protein in primary non-small-cell-lung cancer and metastatic sites: implications for treatment with EGFR-inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:981–985. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taguchi F, Solomon B, Gregorc V, et al. Mass spectrometry to classify non-small-cell lung cancer patients for clinical outcome after treatment with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a multicohort cross-institutional study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:838–846. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macarulla T, Ramos FJ, Elez E, et al. Update on novel strategies to optimize cetuximab therapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2008;7:300–308. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2008.n.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pirker R, Pereira JR, Szczesna A, et al. Cetuximab plus chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (FLEX): an open-label randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1525–1531. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baselga J, Rosen N. Determinants of RASistance to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor agents. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1582–1584. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.3700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tol J, Koopman M, Cats A, et al. Chemotherapy, bevacizumab, and cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:563–572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asahina H, Yamazaki K, Kinoshita I, et al. A phase II trial of gefitinib as first-line therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:998–1004. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sequist LV, Martins RG, Spigel D, et al. First-line gefitinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harboring somatic EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2442–2449. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugio K, Uramoto H, Onitsuka T, et al. Prospective phase II study of gefitinib in non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations. Lung Cancer. 2009;64:314–318. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pao W, Miller VA, Politi KA, et al. Acquired resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib is associated with a second mutation in the EGFR kinase domain. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eberhard DA, Johnson BE, Amler LC, et al. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor and in KRAS are predictive and prognostic indicators in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy alone and in combination with erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5900–5909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massarelli E, Varella-Garcia M, Tang X, et al. KRAS mutation is an important predictor of resistance to therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2890–2896. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]