Abstract

Targeted delivery of a 17-mer antisense phosphorothioate oligodeoxyribonucleotide, complementary to the common 5′-end of every mRNA of the parasite cells, to the phagolysosomes of cultured murine macrophages infected with Leishmania mexicana amazonensis selectively and efficiently eliminated the parasite cells without causing any detectable harm to the host cells. The antisense mini-exon oligonucleotide (ASM) was encapsulated into liposomes coated with maleylated bovine serum albumin (MBSA), the artificial ligand for macrophage scavenger receptors. MBSA-coating of the liposomes allowed specific binding of the liposomes to the macrophages, their receptor-mediated uptake, and subsequent degradation of the liposomes inside macrophage phagolysosomes to release ASM. When incubated with Leishmania-infected macrophages, MBSA–liposome-encapsulated ASM (10 µM) was able to kill >90% of the parasites within 5 hr as compared with 20% killing within this time period by free ASM. Oligonucleotides with complementary nucleotide sequence or with the same base composition as ASM but scrambled sequence had no antileishmanial effect under the conditions of the assay. This study reflects the efficacy of scavenger–receptor-mediated delivery of antisense phosphorothioate oligos in killing intraphagolysosomal pathogens.

Keywords: Leishmania, macrophage, mini-exon, antisense, receptor-medicated targeting, scavenger receptor

In the human parasitic disease leishmaniasis, the acidophilic parasite invades mammalian macrophages and propagates inside the phagolysosomes [1]. Antileishmanial drugs used currently for chemotherapy, such as antimonials, pent-amidine and amphotericin B, often show toxic side-effects [2]. These toxic effects are probably due to longer dwelling time of the drug in the blood and the relatively high blood concentration of the drug necessary for effective drug delivery and action. Liposomal encapsulation of drugs [3] and receptor-mediated targeted delivery of drugs [4–6] have been shown to be possible improvements over this limitation of antileishmanial chemotherapy. The designing of a drug with specificity exclusively towards Leishmania remains to be an immense hurdle to overcome.

A relatively new paradigm of drug discovery and development, which recently has produced substantial enthusiasm in researchers, is the use of antisense oligonucleotides as therapeutic agents [7, 8], In 1994, Ramazeilles et al. [9] demonstrated that antisense targeting of the 5′-terminal sequence common to all leishmanial mRNAs resulted in effective elimination of leishmanial amastigotes from 20–30% of the infected cultured macrophages. The present study describes an improved modality of the antisense phosphorothioate oligonucleotide delivery directly to the parasite-laden phagolysosomes of Leishmania-infected macrophages, exploiting exquisite specificity and abundance of the macrophage scavenger–receptor system [6, 10–12]. The scavenger receptors are integral membrane proteins whose ability to bind and degrade modified low density lipoprotein has implicated them in the process of atherosclerotic foam cell formation [10–12]. These receptors are abundantly but exclusively present on the surface of a mammalian macrophages and macrophage-like cells including the J774G8 lines of mouse macrophage cells [4–6]. The high affinity of MBSA† for this receptor [4–6] has been exploited here for antisense oligonucleotide targeting to macrophages. The experimental approach described here shows that it is possible to target highly specific antisense phosphorothioate oligonucleotides to macrophages, avoiding long dwelling time and high concentration of the drug in the blood of the patient.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells

Leishmania mexicana amazonensis cells (strain LV78) were used throughout this study. These cells were maintained at 25 ± 1° as flagellated promastigotes by weekly passage in Medium 199 plus 10% heat-inactivated (56° for 30 min) fetal bovine serum [13]. The promastigotes of the parasite were grown in the same liquid medium at 25 ± 1°. Amastigotes of L. m. amazonensis (LV78) were grown inside cultured J774G8 cells and purified by Percoll density gradient centrifugation [13]. J774G8, a line of mouse macrophage-like cells, was maintained at 33–35° in medium RPMI 1640 with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum [13]. The Leishmania and J774G8 cells were gifts from Prof. K-P. Chaing of the Chicago Medical School.

Oligonucleotides

Three different phosphorothioate ODNs (S-oligos) were tested in this study: ASM, 5′-CTGATACTTATATAGCG-3′ which is complementary to part of the mini-exon sequence of all leishmanial mRNAs [9]; cASM, 5′-CGCTATATAAGTATGAG-3′, which is complementary to ASM and should not bind to leishmanial mRNAs; and SSM, 5′-TACGTTCATTAAGATGC-3′, which has identical nucleotide composition to ASM but the sequence of the nucleotides is scrambled. Phosphorothioate oligonucleotides were custom synthesized (Cruachem, Inc., Dulles, VA). All the internucleoside linkages in the S-oligos used were phosphorothioate linkages. Oligonucleotides were purified by electrophoresis through a denaturing polyacrylamide gel, followed by Sep-Pak C18 (Millipore Corp., Milford, MA) reversed-phase column chromatography [14, 15].

In Vitro Translation of Leishmania RNA

Poly(A)+ mRNA was purified directly from pelleted and washed promastigotes of L. m. amazonensis using Quick-prep micro mRNA purification reagents (Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, NJ). A wheat germ extract in vitro translation system (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) was used to translate 0.5 µg L. m. amazonensis poly(A)+ mRNA or 0.5 µg CAT mRNA to incorporate [35S]methionine at 30° for 60 min in a total volume of 30 µL, following the supplier′s protocol (Promega Corp.). The reaction mixture was treated with pancreatic RNase A (0.1 µg/mL) for 15 min at 30° to digest radiolabeled methionyl tRNA. Aliquots (10 µL) were spotted on GF/C filters, and the proteins were precipitated by treating the filters in 10% ice-cold TCA for 10 min. The filters were washed subsequently with 5% ice-cold TCA and ethanol, and radioactivity in the filters was determined by liquid scintillation counting [14, 15].

Preparation of MBSA-Coated Liposomes

BSA was maleylated by the reaction of the protein with maleic anhydride [4]. Dipalmitoyl phosphatidylethanol-amine (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO) (100 mg, dissolved in 0.15 M NaCl by ultrasonication) was coupled to MBSA (30 mg) by the 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (100 mg) mediated reaction [4] in a total volume of 3 mL. DMPC was used to prepare liposomes for encapsulation of ASM or other oligonucleotides [13]. Briefly, DMPC (10 mg) was made into vesicles with cholesterol (9 µmol) and dicetyl phosphate (1.2 µmol) in 1 mL HBS (HEPES buffer, 25 mM; NaCl 0.15 M; sometimes contained oligonucleotide, 50 µmol/mL and 125I-labeled BSA, 100 µg/mL). Typically by this procedure 0.1 to 0.2 µmol ASM became trapped in 1 mg of liposomal phospholipids. The amount of phospholipids in each liposomal preparation was assayed by estimating its phosphate content [13]. For coating the liposomes with phospholipid-tailed MBSA, 200 µg of the protein was incubated with 1 mg of liposomes in HBS for 20 hr at 4°. Bound MBSA was separated from unbound molecules by centrifugation at 100,000 g for 1 hr at 4°, as described [13].

Assay of Binding, Uptake, and Degradation of Coated Liposomes by Macrophages

Cultured J774G8 macrophages were washed with HBS and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium with 50 mM HEPES, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 50 µg/mL gentamycin at 2 × 106 cells/mL. Macrophage suspension was dispensed in 0.5-mL aliquots into 35 mm plastic petri dishes. The liposomal preparations suspended in the same medium were filter-sterilized (0.4 µm) and added to the macrophage suspension. Uptake and degradation of liposomes containing 125I-labeled BSA were determined, as described before [4, 5, 13].

Assay of Leishmanicidal Activity of ASTM

Monolayers of J774G8 cells in 35 mm plastic petri dishes were incubated at 37° with L. m. amazonensis promastigotes in medium RPMI 1640 with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum with a parasite to macrophage ratio of 10:1. After 5 hr of incubation, the infected cells were washed with HBS to remove the unabsorbed parasites [4, 5]. The infected macrophages were incubated for 48 hr in the growth medium at 33°. The growth medium of the cells was replaced with fresh medium, and the test compound preparation was added. After incubation of the parasite-laden macrophages at 33° for up to 25 hr, the number of the amastigotes per 100–200 macrophages was counted microscopically, as described [4, 5]. In kinetics experiments, the infected cells were incubated with the test compound for up to 5 hr; then cells were washed with fresh medium and incubated for an additional 20 hr with fresh medium before counting of the amastigotes.

Cytotoxicity Assay In Vitro

The cytotoxicity of ASM to cultured macrophages (J774G8 cells) was assayed by the [3H]thymidine uptake assay, as described [16]. Briefly, 1 × 105 cells/well were incubated overnight (16 hr) in 1 mL RPMI 1640 + 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum at 33°. Each well received 0–10 µM ASM in free or liposome-encapsulated form, and the cells were incubated for 30 min at 33°. Then the cells were washed three times in the culture medium and incubated in ASM-free medium at 33°. After the indicated period of incubation, [3H]thymidine (5 µCi/mL) was added to each well. After 3 hr, the cells were washed three times with 1 mL medium to remove unincorporated radioactivity. The cells in each well were dissolved in 0.5 mL of 100 mM NaOH, and the radioactivity associated with the cells was determined by scintillation counting.

RESULTS

Inhibition of In Vitro Translation of Leishmanial mRNAs by the Test Antisense Oligonucleotide

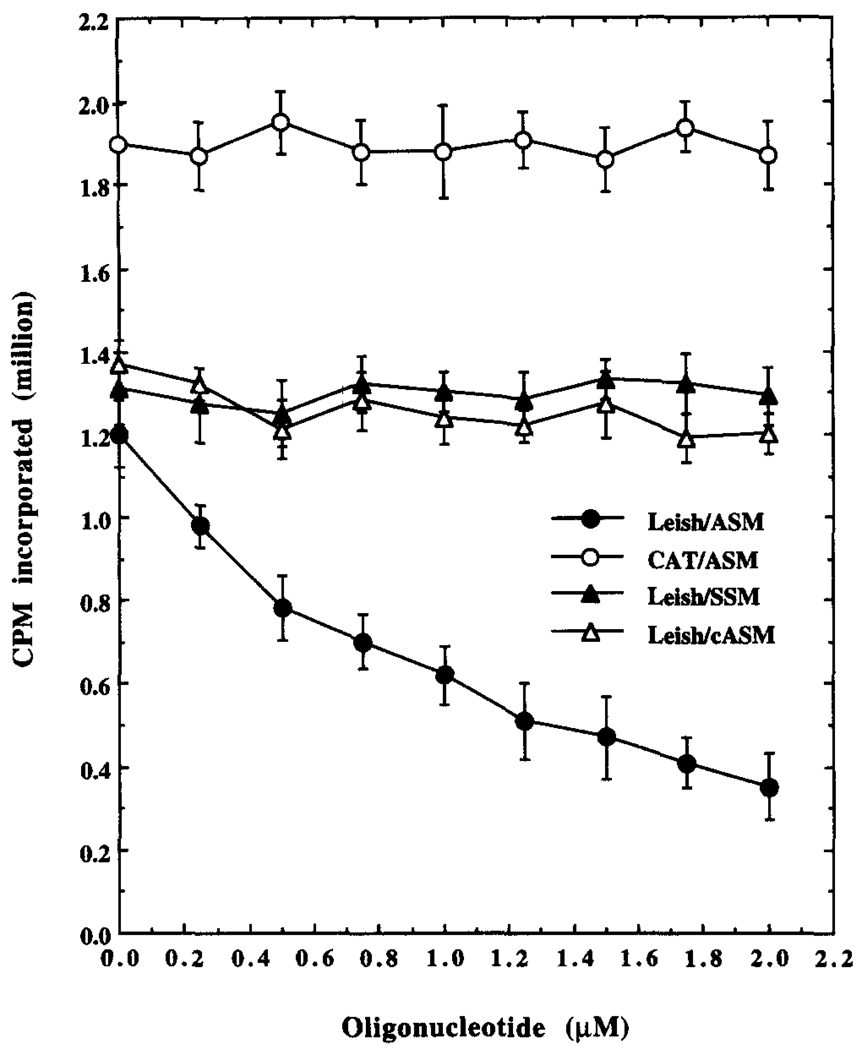

Three kinds of oligonucleotides were tested in this study: the antisense mini-exon phosphorothioate oligonucleotide called ASM, the complementary sequence to ASM called cASM, and the scrambled sequenced 17-mer called SSM (see Materials and Methods). ASM, but not cASM or SSM, could inhibit the translation of the Leishmania mRNAs in vitro (Fig. 1), showing sequence specificity of the inhibition. In vitro translation of CAT mRNA, which lacks the ASM binding site, was not inhibited by ASM under similar conditions (Fig. 1). The phosphodiester derivative of ASM also similarly inhibited the in vitro translation of leishmanial mRNA (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Inhibition of in vitro translation of leishmanial mRNAs by the test antisense oligonucleotide. The effects of different concentrations of ASM on the incorporation of radioactivity from [35S]-methionine into the CAT mRNA (CAT/ASM) or L. m. amazonensis mRNA (Leish/ASM) and of SSM on L. m. amazonensis mRNA (Leish/SSM) translation products are shown. The effect of cASM, the oligonucleotide with sequence complementary to ASM, is also shown (Leish/cASM). Results are the means ± SEM of five independent experiments.

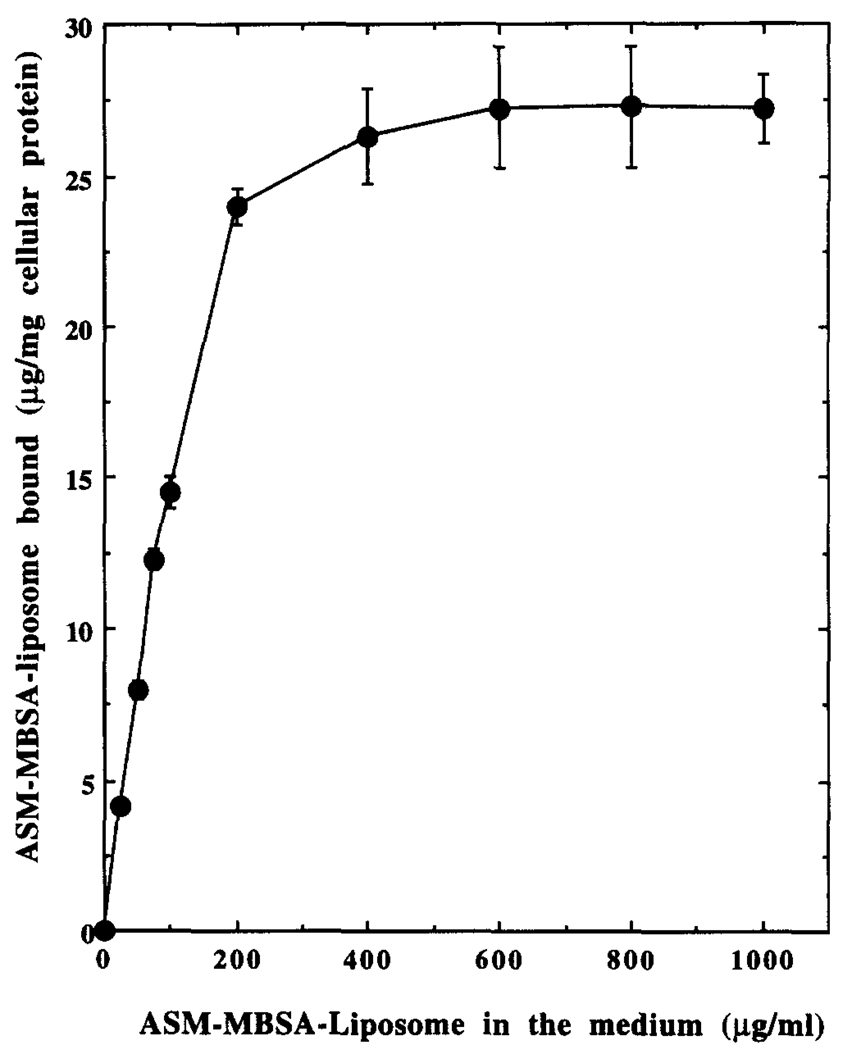

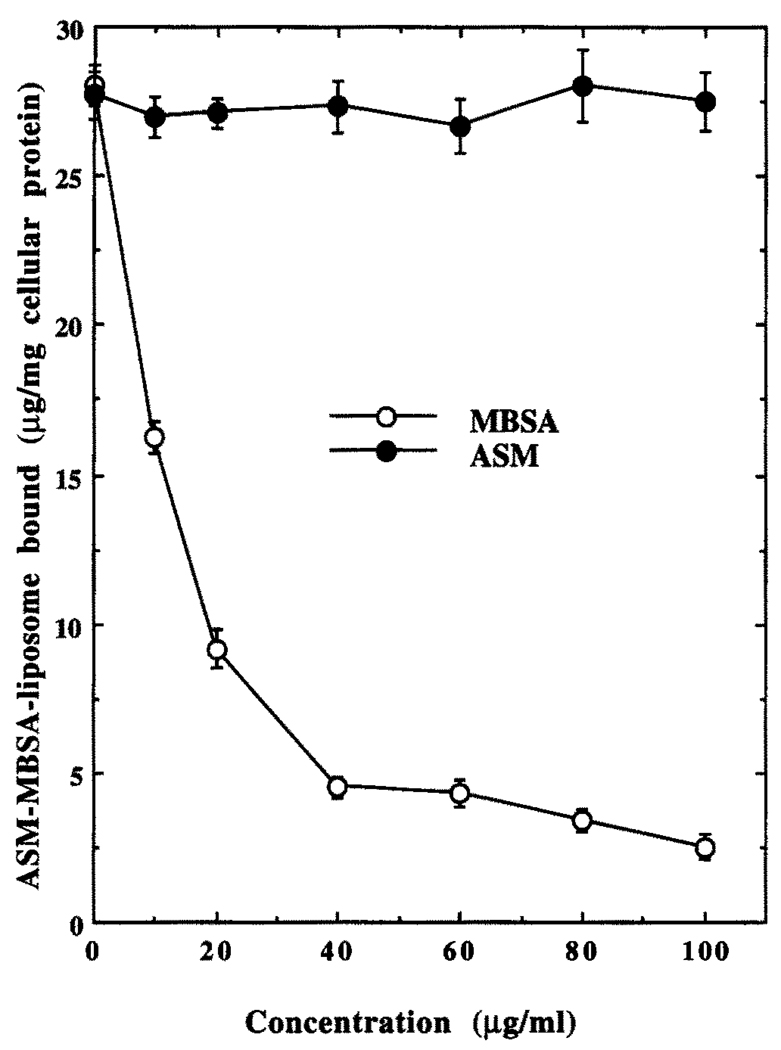

Binding of 125I-Labeled ASM–MBSA–Liposome to J774G8 Cells at 4°

The J774G8 macrophages were incubated with increasing concentrations of labeled liposomal preparation for 2 hr at 4° to determine the nature of interaction of these liposomes with the cells. After thorough washing, the radioactivity associated with the macrophages was assayed. At 4°, the endocytic activity of the macrophages is minimum [4], and the cell-associated radioactivity solely reflects the binding of the ligand-coated liposomes to scavenger receptors on the macrophage cell surface. As expected for a receptor-mediated process, this binding of 125I-labeled ASM–MBSA–liposome to J774G8 cells at 4° followed a saturation kinetics (Fig. 2). Half-maximal binding occurred at about 100 µg/mL of the liposome. This binding was competitively inhibited by the ligand of the scavenger receptor, i.e. MBSA, but not by ASM (Fig. 3), also indicating receptor-mediated binding. MBSA-coated liposomes without encapsulated BSA or ASM, but not the uncoated liposomes, also concentration-dependently inhibited this binding (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Binding of 125I-labeled ASM–MBSA–liposome to J774G8 cells at 4°. Results are the means ± SEM of five independent experiments.

FIG. 3.

Effect of MBSA and ASM on 125I-labeled ASM–MBSA–liposome binding by J774G8 cells at 4°. Results are the means ± SEM of five independent experiments.

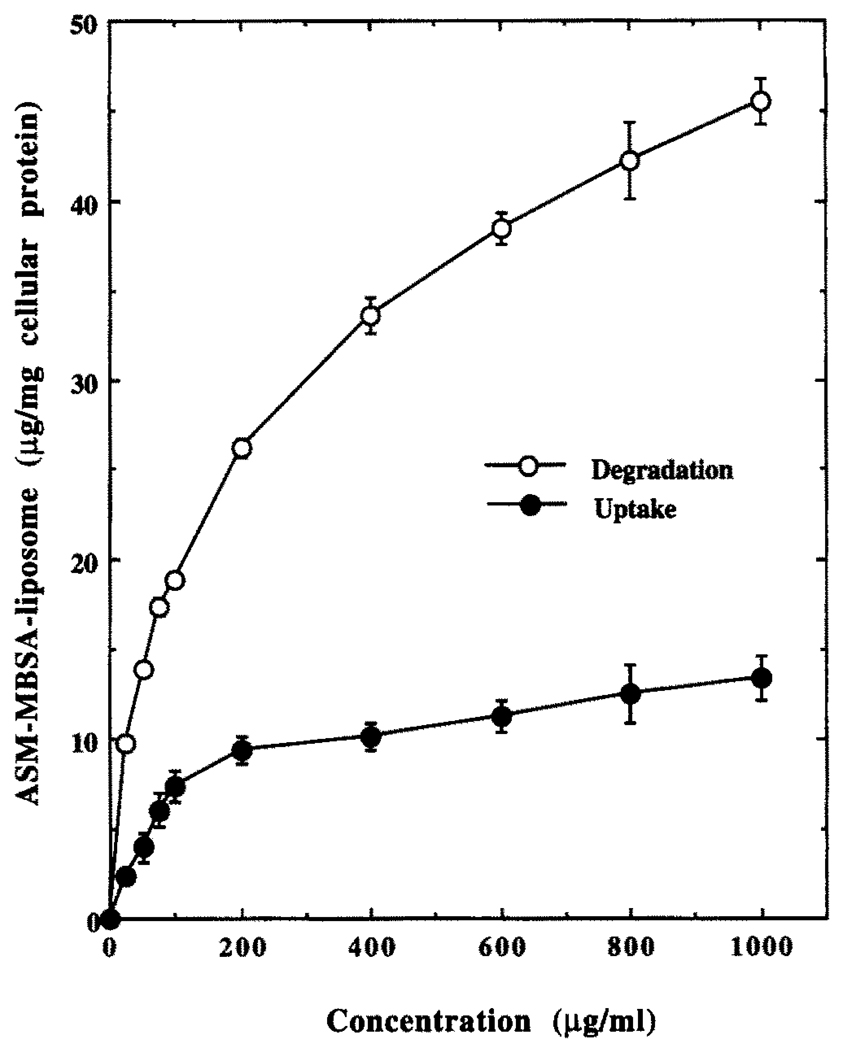

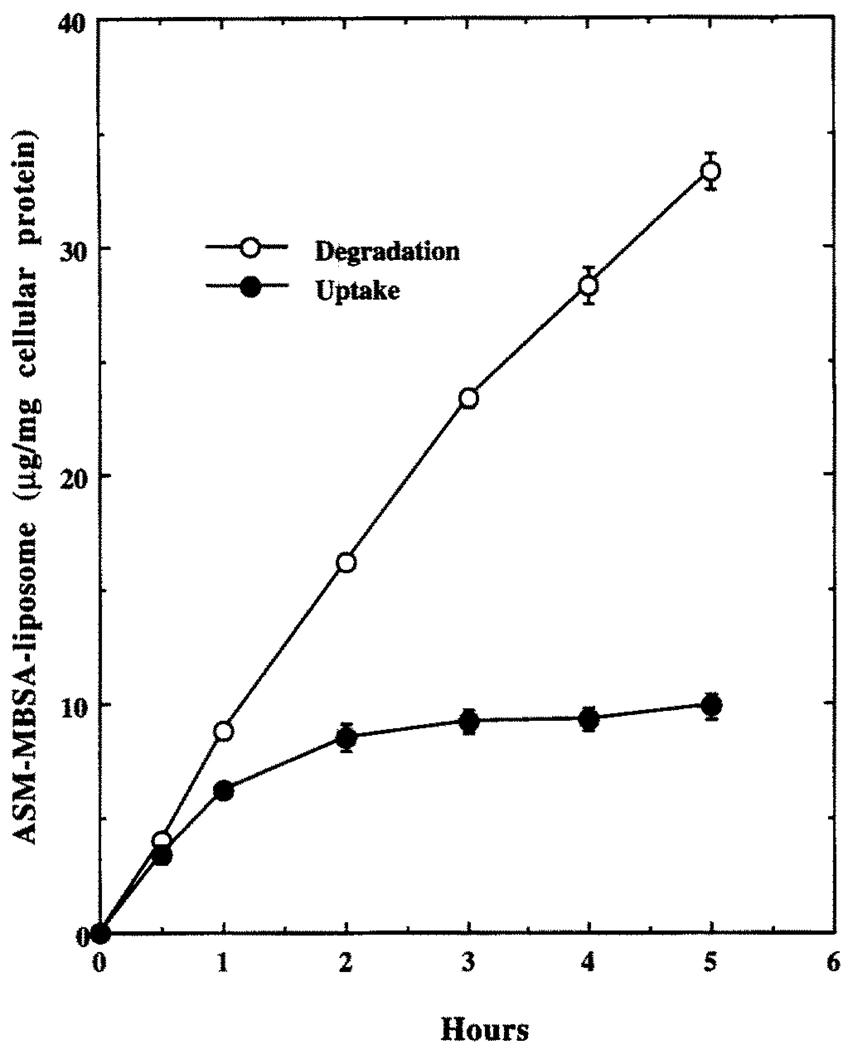

Concentration and Time Dependence of Uptake and Degradation of 125I-Labeled ASM–MBSA–Liposome by J774G8 Cells at 37°

J774G8 cells took up (documented by cell-associated radioactivity) and degraded (documented by the TCA-soluble radioactivity in the spent medium) labeled liposomes in a concentration- (Fig. 4) and time-(Fig. 5) dependent manner when incubated at 37°. The cell-associated radioactivity reached a steady-state plateau after about 2 hr but the TCA-soluble radioactivity in the spent medium continued to increase linearly, indicating continuous uptake and degradation of the liposome conjugate inside the cell (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

Concentration dependence of uptake and degradation of 125I-labeled ASM–MBSA–liposome by J774G8 cells at 37°. Results are the means ± SEM of five independent experiments.

FIG. 5.

Time–course of uptake and degradation of 125I-labeled ASM–MBSA–liposome by J774G8 cells at 37°. Results are the means ± SEM of five independent experiments.

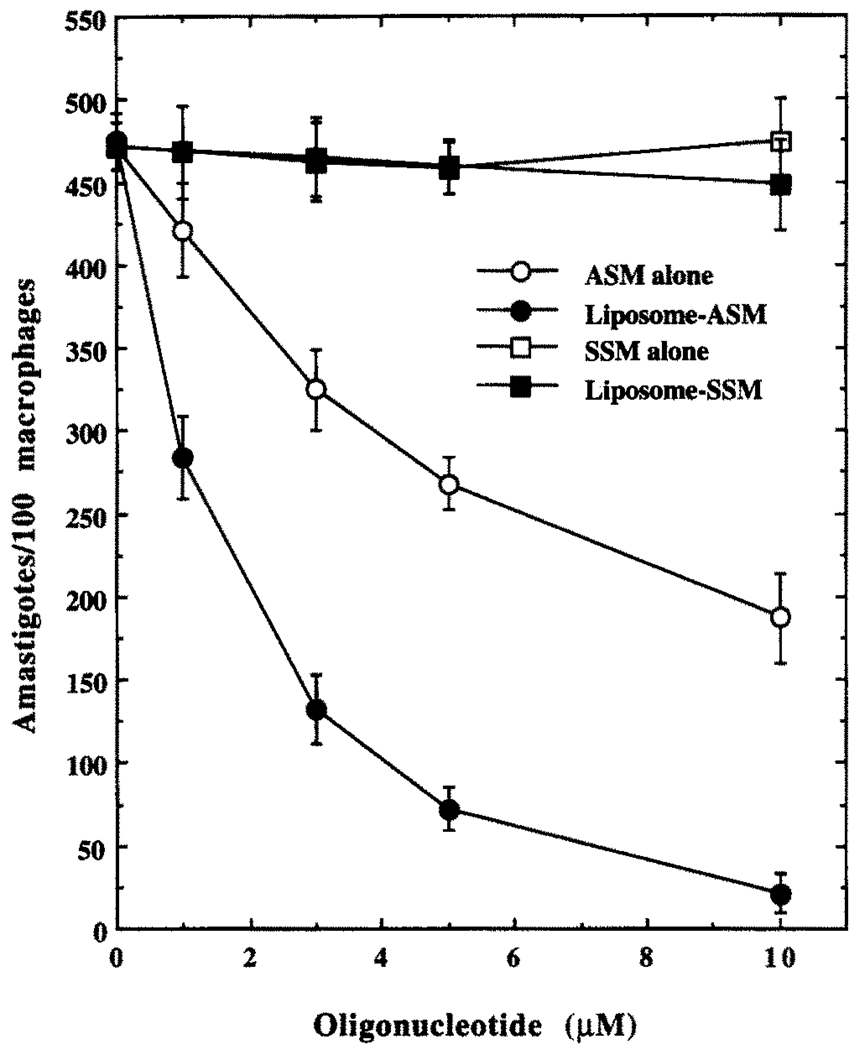

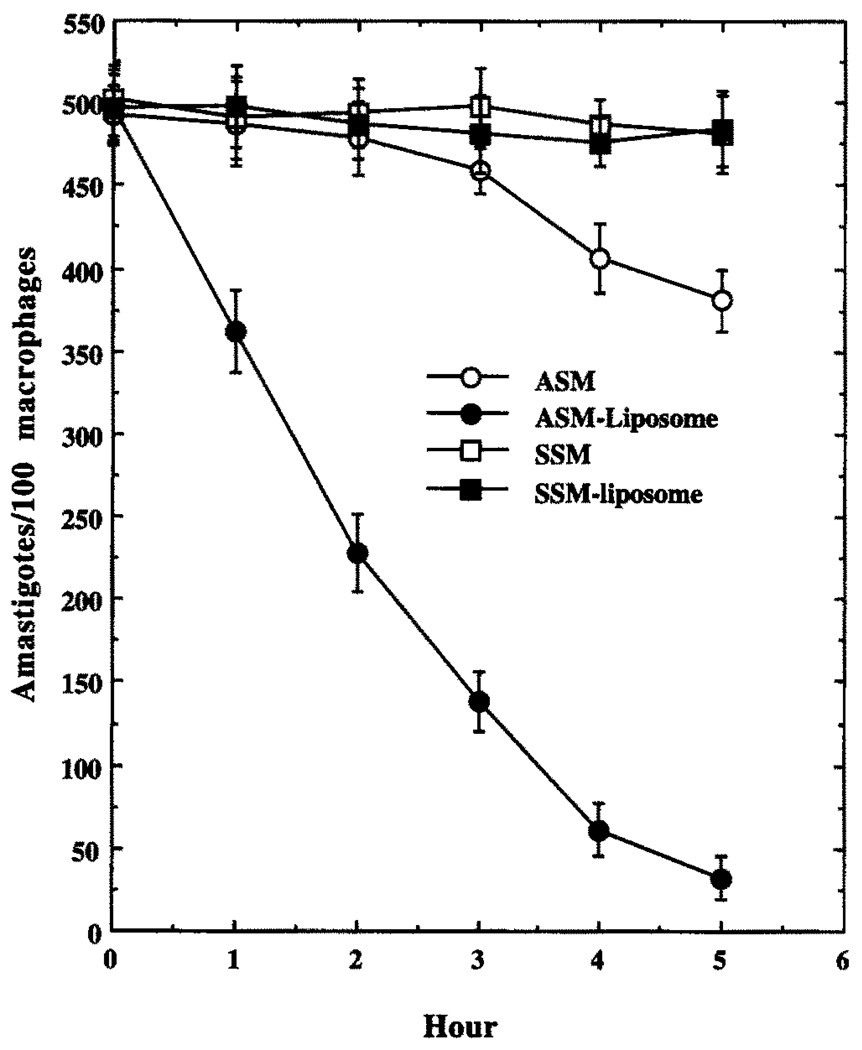

Antileishmanial Effects of SSM, ASM, or ASM–MBSA–Liposome in J774G8 Cells

Both free and liposome-encapsulated ASM showed considerable antileishmanial prowess in the L. mexicana-infected macrophage system at 10 µM (Fig. 6), whereas free or liposome-encapsulated SSM failed to show any significant antileishmanial activity at this concentration. At 10 µM, free ASM also showed a 95% killing effect against L. mexicana cultured promastigotes (data not shown). Neither MBSA nor the liposomes alone at equivalent concentrations had any significant antileishmanial effect (data not shown). Liposome-encapsulated ASM (10 µM) eliminated more than 90% of the L. mexicana amastigotes from infected (90%, 4–7 amastigotes/average macrophage) macrophages when incubated in the growth medium for 5 hr followed by continuous incubation for 20 hr in drug-free medium, whereas an equivalent concentration (10 µM) of free ASM (or ASM encapsulated in liposomes that were not coated with MBSA) with continuous incubation for 25 hr resulted in about 50% killing of the amastigotes (Figs. 6 and 7). Incubation of free ASM (10 µM) with the infected macrophages for 5 hr followed by a 20-hr incubation in drug-free medium resulted in only about 20% killing of the amastigotes (Fig. 7). Prolonged incubation (20 hr) with free ASM (10 µM) cured completely only 20–25% of the infected macrophages, whereas a similar curing was done by the same concentration of ASM for 1 hr when presented as encapsulated in MBSA-coated liposomes. The antileishmanial activity of liposome-encapsulated ASM was inhibited by MBSA and the inhibitor of lysosomal activity, chloroquine, whereas this activity of free ASM remained unaffected by the presence of these agents (Table 1). As reported previously [4], these MBSA-tagged liposomes are cleared from the blood of Balb/C mice very quickly (98% within 10 min of injection through the femoral vein) and are accumulated in macrophage-rich tissues like spleen and liver (data not shown), as expected. Under the conditions of the experiments described (see Materials and Methods), free ASM or liposome-encapsulated ASM had no effect on the growth of J774G8 macrophages, as was indicated by incorporation of radiolabeled thymidine into the DNA of these cells (see Materials and Methods, data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Comparison of antileishmanial effects of SSM (□), SSM–MBSA–liposome (■), ASM (○) or ASM–MBSA–liposome (●) in infected J774G8 cells. cASM, the oligo-nucleotide with sequence complementary to ASM, failed to show any inhibition under similar conditions (data not shown). Results are the means ± SEM of five independent experiments.

FIG. 7.

Time–course of killing of L. m. amazonensis amastigotes in J774G8 cells by SSM (□), SSM–MBSA–liposome (■), ASM (○) or ASM–MBSA–liposome (●). cASM, the oligonucleotide with sequence complementary to ASM, failed to show any inhibition under similar conditions (data not shown). Results are the means ± SEM of five independent experiments.

TABLE 1.

Inhibition of antileishmanial activity of ASM–MBSA–liposome by MBSA and chloroquine

| No. of amastigotes/100 macrophages† | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Addition* | Untreated control |

ASM | ASM–MBSA– liposome |

| None | 492 ± 21 | 261 ± 23 | 31 ± 7 |

| MBSA (100 µg/mL) | 504 ± 27 | 247 ± 21 | 506 ± 31 |

| Chloroquine (3 µM) | 482 ± 29 | 233 ± 27 | 483 ± 19 |

Cells were treated with the compound in the growth medium for 10 min before the addition of the drug.

Results are the means ± SEM of five independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

ODNs have become widely used as potential chemotherapies as well as research tools [17, 18]. By blocking the expression of a gene in a sequence-specific manner, antisense ODNs can provide very useful information on the function of the gene of interest or can eliminate a parasite from the infected host cells without affecting the host system. These short single-stranded DNA molecules can be designed to hybridize locally with either cellular DNA (triplex ODNs) or RNA (antisense ODNs) and to interfere with subsequent transcription or translation, respectively [7, 8, 17, 18].

The post-transcriptional modification that must happen to a leishmanial mRNA before it can be translated into protein is the transplicing reaction that puts a 35 nucleotide cap at the 5′-end of the mRNA [9], Targeting this unique 5′-end sequence of the parasite mRNAs to bind with the antisense S-oligo perhaps makes those targeted mRNAs unsuitable for translation or otherwise susceptible to RNase H-like enzymes of Leishmania, resulting in their degradation [9]. The presence of RNase H-like enzymes has been documented in a related protozoan, Crithidia fasciculata [19], and mRNA hybridizable to this gene probe has been detected in L. m. amazonensis (Chaudhuri G, unpublished results).

For successful use, the ODN must be stable inside the target cells. Conventional phosphodiester oligonucleotides are usually degraded inside the cell due to the presence of DNases (both endo- and exonucleases) [3]. Particularly, in the case of the leishmanial parasite residing in the lytic milieu of macrophage phagolysosomes, any phosphodiester oligonucleotides targeted to that compartment to kill the parasites are obviously degraded before they can enter the parasite cells to be effective. Although we have not tried the methylphosphonate or phosphotriester derivatives of the anti-mini-exon ODN for their comparative efficacies in killing Leishmania amastigotes in infected macrophages, the phosphorothioate but not the phosphodiester derivative of ASM was found to have significant antileishmanial activity.

A major hurdle in targeting an intracellular parasite like Leishmania with an antisense S-oligo is that the S-oligo has to cross the host membranes (the plasma membrane and the phagolysosomal membrane) to reach the parasite cells. While the transport mechanism(s) of S-oligos across leishmanial membrane is yet to be understood, an effort was made to directly deliver the ASM S-oligos to the parasitophorus vacuoles of Leishmania-infected macrophages. The S-oligo was encapsulated inside DMPC liposomes and those liposomes were then coated with phosphatidylethanol-amine-tagged MBSA. The anionic protein MBSA is an efficient ligand of the group A type I and type II scavenger receptors of mammalian macrophages [10–12]. This receptor system was chosen as a route for the introduction of S-oligos to the phagolysosomes because these receptors are exclusively expressed abundantly on the surface of mature macrophages only at later stages of their differentiation [11, 12], have no apparent ligand-induced down-regulation [6] and have been shown [4] to be effective in rapidly clearing the ligand-bound drug from the extracellular medium to the phagolysosomes of macrophages.

Here, the liposome-bound MBSA is shown to be as effective as free MBSA in binding to cultured macrophages following a saturable kinetics and is capable of carrying the liposomes to the phagolysosomes. Inside this compartment, these liposomes are possibly disrupted by acid-phospholipases to empty their contents, which become amenable to phagolysosomal degradation. Radioiodinated BSA was used as a tracer both to measure the amount of S-oligo inside the liposomes and to monitor the binding, uptake, and degradation of liposomes [4–6]. Encapsulation of ASM in MBSA-coated liposomes and addition of this conjugate to the culture medium of Leishmania-infected macrophages possibly resulted in rapid accumulation of the antisense S-oligo in the immediate vicinity of Leishmania amastigotes to kill them by inhibiting the general expression of their mRNAs. Intact lysosomal activity is required for the ASM–MBSA–liposome to show leishmanicidal effects, as chloroquine, an inhibitor of lysosomal function, resisted the activity of this drug conjugate. Perhaps this is due to the blockage of liposomal disruption by the acid hydrolases of the phagolysosomes to liberate the ASM into the phagolysosomal milieu.

This study further emphasizes the potential of targeted delivery of antisense S-oligos in curing mammalian macrophages from parasite infection. Although effective, ASM is needed at a relatively high concentration to be useful as an antileishmanial agent. This is partly because it has only 35% GC content, and thus its binding to the target sequence is weak. Identification and characterization of genes important for the maintenance of leishmanial infection inside macrophages and the development of strategies to help the antisense oligos to cross leishmanial membrane should improve the efficiency of combating this and other similar deadly human diseases.

Acknowledgments

I thank Mrs. Angelika K. Parl for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by NSF Research Center for Excellence in Cell and Molecular Biology Grant HRD-9255157 and NIH Grant 2 S06 GM 08037-24.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ASM, antisense mini-exon oligonucleotide; SSM, scrambled sequence to mini-exon oligonucleotide; cASM, complementary sequence to ASM; MBSA, maleylated bovine serum albumin; ODN, oligodeoxyribonucleotide; DMPC, dimyristoyl phosphatidyl choline; TCA, trichloroacetic acid; and CAT, chloramphenicol acetyl transferase.

References

- 1.Zilberstein D, Shapira M. The role of pH and temperature in the development of Leishmania parasites. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:449–470. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.002313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berman JD. Experimental chemotherapy of leishmaniasis—A critical review. In: Chang KP, Bray RS, editors. Leishmaniasis. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1985. pp. 111–138. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alving CR. Liposomes as drug carriers in leishmaniasis and malaria. Parasitol Today. 1986;2:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(86)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhuri G, Mukhopadhyay A, Basu SK. Selective delivery of drugs to macrophages through acetyl low-density lipoprotein receptor: An efficient chemotherapeutic approach against leishmaniasis. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;38:2995–3002. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukhopadhyay A, Chaudhuri G, Arora SK, Sehgal S, Basu SK. Receptor-mediated drug delivery to macrophages in chemotherapy of leishmaniasis. Science. 1989;244:705–707. doi: 10.1126/science.2717947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basu SK. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of macromolecular conjugates in selective drug delivery. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;40:1941–1946. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner RW. Gene inhibition using antisense oligodeoxy-nucleotides. Nature. 1994;372:333–335. doi: 10.1038/372333a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein CA, Narayanan R. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotides. Curr Opin Oncol. 1994;6:587–594. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199411000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramazeilles C, Mishra RK, Moreau S, Pascolo E, Toulmé J-J. Antisense phosphorothioate oligonucleotides: Selective killing of the intracellular parasite Leishmania amazonensis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7859–7863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.7859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Atherosclerosis. Scavenging for receptors. Nature. 1990;343:508–509. doi: 10.1038/343508a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rohrer L, Freeman M, Kodama T, Penman M, Krieger M. Coiled-coil fibrous domains mediate ligand binding by macrophage scavenger receptor type II. Nature. 1990;343:570–572. doi: 10.1038/343570a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kodama T, Freeman M, Rohrer L, Zabrecky J, Matsudaira P, Krieger M. Type I macrophage scavenger receptor contains α-helical and collagen-like coiled coils. Nature. 1990;343:531–535. doi: 10.1038/343531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaudhuri G, Chaudhuri M, Pan A, Chang KP. Surface acid proteinase (gp63) of Leishmania mexicana: A metallo-enzyme capable of protecting liposome-encapsulated proteins from phagolysosomal degradation by macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:7483–7489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ausubel M, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: John Wiley; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukhopadhyay A, Mukhopadhyay B, Srivastava RK, Basu SK. Scavenger-receptor-mediated delivery of daunomycin elicits selective toxicity towards neoplastic cells of macrophage lineage. Biochem J. 1992;284:237–241. doi: 10.1042/bj2840237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein CA, Cheng YC. Antisense oligonucleotides as therapeutic agents—Is the bullet really magical? Science. 1993;261:1004–1012. doi: 10.1126/science.8351515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown T, Brown JS. Modern machine-aided methods of oligodeoxyribonucleotide synthesis. In: Echstein F, editor. Oligonucleotides and Analogues: A Practical Approach. New York: IRL Press; 1991. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell AG, Ray DS. Functional complementation of an Escherichia coli ribonuclease H mutation by a cloned genomic fragment from the trypanosomatid Crithidia fasciculata. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9350–9354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]