Abstract

Background

Impairment in intrinsic foot mobility has been identified as an important potential contributor to altered foot function in individuals with Diabetes Mellitus and neuropathy, however the role of limited foot mobility in gait remains poorly understood. The purpose of our study was to examine segmental foot mobility during gait in subjects with and without diabetes and neuropathy.

Methods

Segmental foot mobility during gait was examined using a multi-segment kinematic foot model in subjects with diabetes (n=15) and non-diabetic control subjects (n=15).

Findings

Subjects with diabetes showed reduced frontal as well as sagittal plane excursion of the calcaneus relative to the tibia. Decreased excursion of the first metatarsal relative to the calcaneus in the frontal as well as transverse plane was noted in subjects with diabetes.

Interpretation

Our findings agree with traditional understanding of foot mechanics and shed new light on patterns and magnitude of motion during gait. Calcaneal pronation, noted in early stance in both groups, was reduced in subjects with diabetes and may have important consequences on joints proximal as well as distal to it. Subjects with diabetes showed reduced foot ‘splay’ in early stance, indicated by first metatarsal and forefoot eversion. At terminal stance, decreases in calcaneal plantarflexion, first metatarsal and forefoot supination were noted in subjects with diabetes, suggesting that less supination is required in subjects with diabetes to create a rigid lever. In subjects with diabetes, a greater proportion of midfoot stability may be derived from modified/stiffer soft tissue such as the plantar fascia.

Keywords: Diabetes, foot mobility, kinematic model

Introduction

Plantar ulcers develop in an estimated 15% of patients with Diabetes Mellitus (DM) [1]. Along with grave consequences in terms of health and functional abilities [2, 3], foot ulcers and associated amputation are often harbingers of personal and financial hardships. Factors contributing to altered foot function and thus the development of foot ulcers are therefore of considerable interest.

Normal foot function during gait requires the foot to transition from a flexible structure that dissipates impact as it contacts the ground to a rigid structure that allows for efficient propulsion during push-off [4]. To reconcile these widely divergent demands, the foot acts as a twisted osteo-ligamentous plate [5], where calcaneal eversion is accompanied by unlocking of the midfoot and concomitant first ray dorsiflexion. Conversely, calcaneal inversion is accompanied by midfoot rigidity and first ray plantarflexion.

Impairments in intrinsic foot mobility have been identified as key factors underlying altered foot function in individuals with DM. Reduced subtalar joint mobility, specifically inadequate calcaneal eversion has been documented in subjects with DM [6–13]. Reduced subtalar mobility may have significant biomechanical consequences [14, 15] including increases in transverse tarsal joint rigidity predisposing to lateral column over-weighting. Similarly, limited first metatarsal mobility [12, 16] has been hypothesized to result in reduced first metatarsal motion during gait in individuals with DM [17] thus predisposing to the development of foot ulcers.

While the first ray is an important component of the twisted plate model of the foot, first ray mechanics in gait are still controversial. Current studies suggest that the first metatarsal is plantarflexed during early stance and continues to dorsiflex about 10 degrees relative to the hindfoot until 70% of stance [18–21]. However, recent evidence demonstrates minimal lowering of the proximal first metatarsal during stance [22] and suggesting that the excursion between the first metatarsal and calcaneus comes predominantly from calcaneal motion.

Evidence substantiating altered foot function as it relates to segmental foot mobility during gait in individuals with DM is limited. The few studies that have used multisegment kinematic models [20, 23–25] have been conducted on non-DM subjects with intact sensation. Their extrapolation to subjects with DM, who have impairments such as loss of protective sensation and increased connective tissue stiffness, may not be valid.

Thus, while intrinsic foot mobility has been identified as an important potential contributor to foot function, especially in individuals with DM, the role of limited foot mobility in gait remains poorly understood. The purpose of our study was to examine segmental foot mobility during gait in subjects with and without DM and neuropathy. These results are important because they may help uncover mechanisms underlying altered segmental foot function in individuals with DM. Altered foot kinematics may also contribute to the development of high loads on the plantar aspect of the foot and thus potential tissue breakdown. An enhanced understanding of foot function in patients with DM may help the development of patient specific foot risk surveillance and suggest strategies for individualized footwear intervention.

Methods

Subjects

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. Subjects with DM and neuropathy (n=15) comprised the study group; non-diabetic subjects (n=15) comprised the control (Ctrl) group. Subjects with DM were included based on the diagnosis of DM (ADA criteria [26]) and excluded if they had:, current foot ulcer, great toe or transmetatarsal amputation, ipsilateral or contralateral Charcot neuroarthropathy or clinical symptoms of other musculoskeletal lower limb pathology. Presence of neuropathy was documented using 5.07 Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments [27] and Vibration Perception Threshold (VPT) of 25 V or higher [28]. Subjects in the control group were screened for diabetes and matched in age and gender to subjects with DM. Subject characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data from study and control groups, expressed as mean (SD).

| DM | Control | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 15 | 15 |

| Age (yrs) | 58 (11) | 56 (12) |

| Gender F:M | 5:10 | 5:10 |

| Height (m) | 1.77 (0.11) | 1.75 (0.10) |

| Mass (kg) | 90.6 (13.8) | 74.6 (13.3) |

| VPT (V) | 48 (5) | 13 (6) |

| HbA1c% | 8.1 (1.1) | |

| Type 2 | 12 ie 80% | |

| Duration (yrs) | 19 (6) |

Data acquisition

Kinematic and kinetic data were acquired as subjects walked along a 10 m walkway at 0.89 m/s (2 mph). An overhead timing chain was used to obtain/monitor walking speed. Kinematic data were collected at 120 Hz using an active marker system (Optotrak, NDI, Waterloo, Canada). Three infrared markers were placed in a non-collinear arrangement to define technical coordinate systems for each of the following segments: first metatarsal, forefoot, calcaneus and leg. Kinetic data were collected at 360 Hz using a forceplate embedded in the walkway (Kistler Inc, Amherst, NY, USA).

Kinematic and kinetic data were low-pass filtered using a fourth order butterworth filter with cut-off frequencies of 6 and 8 Hz respectively and processed using Visual3D software (C-motion Inc., Rockville, MD, USA). A threshold of 10 N was used to determine heelstrike and toe off from the force plate data. Kinematic marker data were used to confirm that subjects were able to achieve and maintain walking speed and to calculate stride length. A minimum of five successful trials were collected for each subject. A trial was considered successful if the subject made clean forceplate contact on the tested side without targeting.

Multisegment kinematic model of the foot

A multi-segment kinematic model of the foot based on Wilken et al [29] was used to examine segmental mobility of the foot. This model has been validated by Wilken et al (2004) and has several strengths. It is anatomically based and lends itself to the creation of subject-specific kinematic models. The foot was segmented into the first metatarsal, calcaneus and forefoot, where first metatarsal and calcaneus segments referred to the underlying bony anatomy while the forefoot segment comprised metatarsals 2 through 5. This definition of the forefoot segment, consistent with previous kinematic models [30, 31] was used to facilitate comparison of results across studies. Motion of the calcaneus relative to the tibia encompasses the talocalcaneal (subtalar) as well as the talocrural (ankle) joints. Results obtained from in vivo cadaver models suggest that the majority of dorsiflexion-plantarflexion motion between the calcaneus and tibia may be attributed to the ankle joint, while abduction-adduction and inversion-eversion may be attributed to subtalar joint. [32, 33] Since the first metatarsal and calcaneus are key elements in the medial longitudinal arch, [34, 35] motion between the first metatarsal and calcaneus is considered representative of motion of the arch. [21, 36, 37] The segments defined in this model have well-grounded conceptual meaning [5], as well as targeted the segments of interest. Anatomical landmarks were identified as virtual points with respect to the relevant technical coordinate system. Anatomically based local coordinate systems were established using the criteria defined in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Definition of Local Co-ordinate Systems [29]

| Segment | Axis | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| First Metatarsal | X Y Z |

Aligned with long axis of first metatarsal |

| Orthogonal to X and Z axes | ||

| Parallel to floor and orthogonal to X axis | ||

| Lateral Forefoot |

X Y Z |

Aligned with long axis of second metatarsal |

| Orthogonal to X and Z axes | ||

| Orthogonal to long axis of second metatarsal and parallel to the floor | ||

| Calcaneus | X Y Z |

Posterior heel to midpoint of foot at the level of the fifth metatarsal flair |

| Calcaneal bisector | ||

| Orthogonal to X and Y axes | ||

| Leg | X Y Z |

Orthogonal to Y and Z axes |

| Passing through midpoint of femoral condyles and malleoli | ||

| Aligned with malleoli and passing through mid malleolar point (orthogonal to Y) |

Table 3.

Marker placement [29]

| Segment | Marker | Location |

|---|---|---|

| First Metatarsal | 1 2 3 |

Mounted on triad on dorsal medial surface of first metatarsal |

| Mounted on triad on dorsal medial surface of first metatarsal | ||

| Mounted on triad on dorsal medial surface of first metatarsal | ||

| Lateral Forefoot |

4 5 6 |

Proximal end of second metatarsal |

| Distal end of second metatarsal | ||

| Distal end of fifth metatarsal | ||

| Calcaneus | 7 8 9 |

Posterior surface of calcaneus |

| Lateral aspect of calcaneus superior to calcaneal fat pad | ||

| Lateral aspect of calcaneus superior to calcaneal fat pad | ||

| Leg | 10 11 12 |

Medial surface of tibia |

| Medial surface of tibia | ||

| Medial surface of tibia |

Motion of the distal segment was expressed relative to the proximal segment [38] and was calculated using Euler angles with the following sequence of rotations: sagittal, frontal and transverse. Motion of each segment relative to the lab global co-ordinate system (GCS) was also examined. While the former convention has widespread clinical relevance, the latter allows us to examine the contribution of each moving segment to relative motion between the two. Processed kinematic data were time normalized to 100 percent stance. Stance phase mean was subtracted from pattern to correct for systematic offsets [31]. The application of this correction eliminates systematic offsets between groups and helps reduce between-subject variability, allowing for comparisons of range, timing and pattern of motion between the study and control groups.

Statistical Analysis

A two-sample t-test was used to assess differences between the two groups (α=0.05). To control Type 1 error rate when performing multiple pair-wise comparisons, an adjusted P-value (α=0.05 per segment) was used to determine statistical significance based on the number of comparisons made.

Results

Subjects in both groups walked with similar speed (0.89 (SD, 0.13) and 0.93(SD, 0.11) m/s, DM and Ctrl respectively, P=0.169) and stride length (1.08 (SD, 0.15) and 1.12(SD, 0.10) m, DM and Ctrl respectively, P=0.166). Because of the differences in BMI the relationships between BMI and kinematic variables were assessed and determined to be not a confounding factor (r2<12%).

Segmental kinematics expressed relative to proximal segment

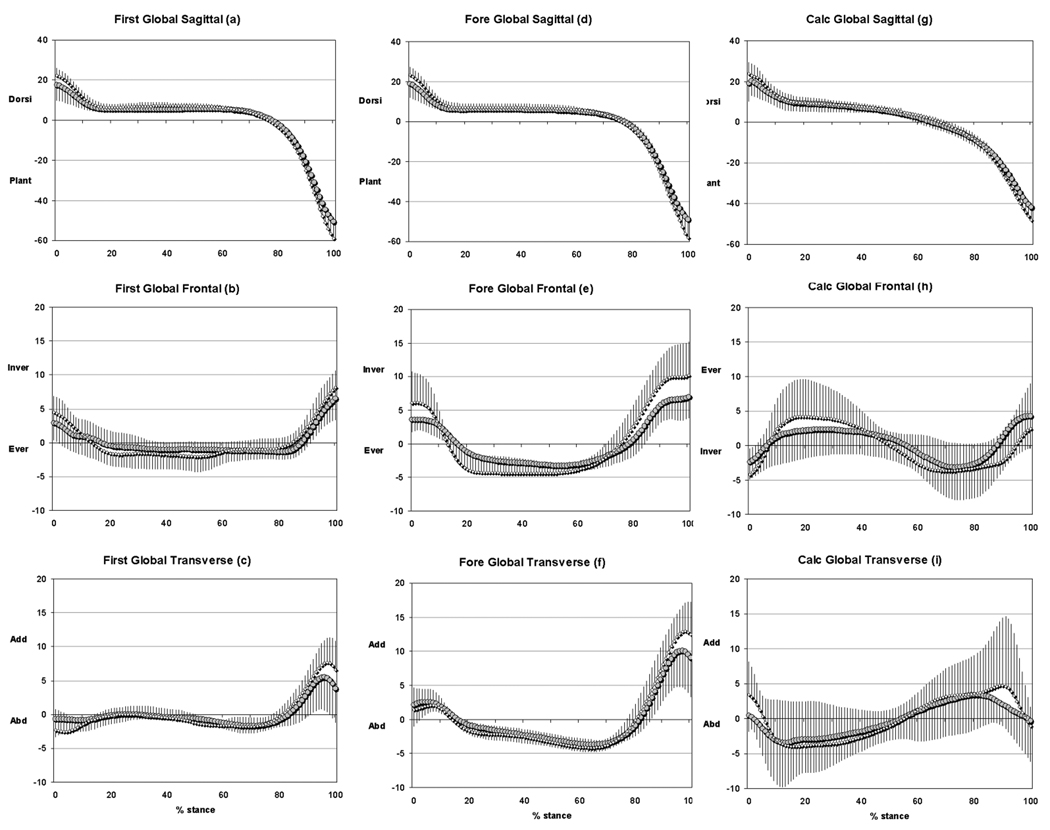

Subjects with DM showed reduced frontal plane excursion of the calcaneus relative to the tibia, accompanied by reduced eversion (Figure 1-h, Table 4). Subjects with DM also showed reduced sagittal plane excursion (Figure 1-g) of the calcaneus relative to the tibia. Decreased excursion of the first metatarsal relative to the calcaneus in the frontal plane (Figure 1-b, Table 4), as well as transverse plane (Figure 1-c), was noted in subjects with DM. Trends towards reduced frontal plane excursion of the forefoot relative to the calcaneus were noted in subjects with DM (Figure 1-e).

Figure 1.

Ensemble averaged kinematics of the first metatarsal, forefoot and calcaneus relative to the proximal segment. Circles represent subjects with DM, Diamonds represent Ctrl subjects; Error bars represent 1SD.

Table 4.

Summary of segmental kinematics, Mean (SD), expressed relative to the proximal segment

| Segment | Plane | Parameter | DM | Ctrl | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

First Metatarsal |

Sagittal | Dorsi | 6.5 (3.8) | 5.6 (1.9) | 0.147 |

| Range | 13.0 (2.5) | 14.7 (3.3) | 0.270 | ||

| Forefoot | Sagittal | Dorsi | 6.4 (2.6) | 5.9 (2.5) | 0.302 |

| Range | 13.8 (3.3) | 15.3(4.0) | 0.139 | ||

| Calcaneus | Sagittal | Dorsi | 5.9 (2.1) | 6.7(2.2) | 0.015 |

| Range | 12.7 (4.3) | 19.6 (4.4) | <0.001 | ||

| Frontal | Ever | 4.5 (2.0) | 6.5 (2.4) | 0.010 | |

| Range | 9.5 (4.3) | 15.0 (3.9) | <0.001 | ||

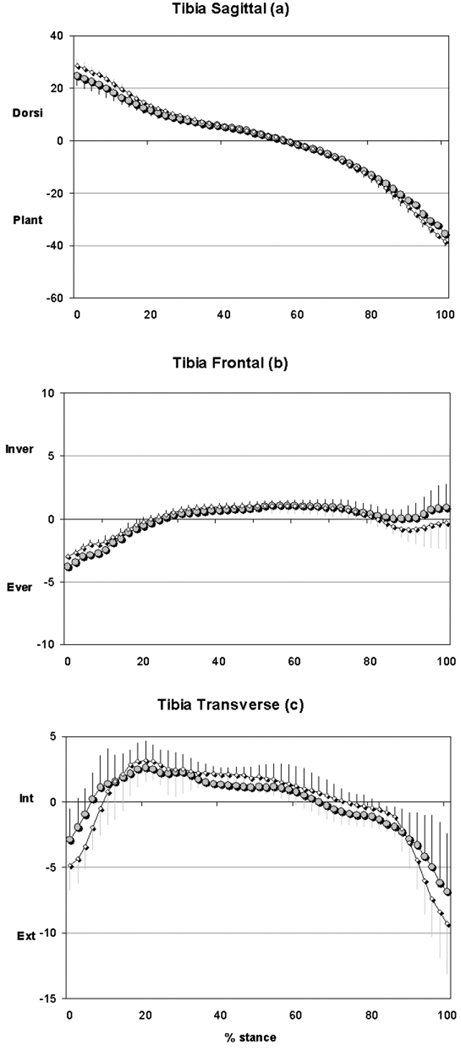

Segmental kinematics expressed relative to the lab

Reduced sagittal plane calcaneal excursion and trends towards reduced frontal plane calcaneal excursion and eversion (Figure 2-h, Table 5) were noted in subjects with DM. The first metatarsal as well as forefoot showed less sagittal plane excursion (Figure 2-a, d, Table 5) in subjects with DM. In addition, the forefoot showed decreased frontal plane excursion in subjects with DM (Figure 2-e), similar trends were noted in the transverse plane (Figure 2-f). Sagittal plane excursion of the tibia was reduced in subjects with DM (Figure 3a, Table 5).

Figure 2.

Ensemble averaged kinematics of the first metatarsal, forefoot and calcaneus relative to the GCS. Circles represent subjects with DM, Diamonds represent Ctrl subjects; Error bars represent 1SD

Table 5.

Summary of segmental kinematics, Mean (SD), expressed relative to the GCS

| Segment | Plane | Parameter | DM | Ctrl | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Ray | Sagittal | Dorsi | 18.3 (6.7) | 22.2 (3.8) | 0.032 |

| Range | 68.8 (12.5) | 81.8 (8.8) | 0.002 | ||

| Forefoot | Sagittal | Dorsi | 19.3 (6.6) | 23.3 (4.3) | 0.032 |

| Range | 68.4 (12.4) | 81.4 (8.7) | 0.001 | ||

| Calcaneus | Sagittal | Dorsi | 22.3 (5.7) | 24.9 (4.1) | 0.077 |

| Range | 64.1 (10.4) | 72.9 (7.2) | 0.006 | ||

| Frontal | Ever | 3.1 (3.0) | 5.2 (3.5) | 0.037 | |

| Range | 9.7 (7.5) | 12.6 (4.6) | 0.021 | ||

| Tibia | Sagittal | Range | 60.0 (7.2) | 66.3 (4.6) | 0.003 |

| Frontal | Range | 5.9 (1.9) | 5.0 (1.5) | 0.145 | |

Figure 3.

Ensemble averaged kinematics of the tibia relative to the GCS. Circles represent subjects with DM, Diamonds represent Ctrl subjects; Error bars represent 1SD

Discussion

We applied a multi-segment kinematic model to examine foot function in individuals with DM and neuropathy compared to non-diabetic control subjects. Our results revealed significant differences in patterns of segmental mobility between the two groups, with DM subjects showing lower magnitudes of motion. The reductions in motion were not generalized – they were particularly dramatic in the calcaneus compared to the forefoot and first metatarsal. Our results underscore the complexity of segmental foot function during gait; motion at one joint has important consequences on motion at neighboring joints. Our findings provide new insights on the nature of impairments in segmental foot function in individuals with DM.

During gait, foot-floor interaction begins with heel contact which places significant demands on the subtalar joint in terms of mobility and shock absorption [4]. In agreement with reports based on surface markers [20, 23, 25, 31, 39–41] as well as bone pins [42], our results showed that the calcaneus undergoes rapid pronation in early stance. In order to examine the contribution of each moving segment to relative motion between the two segments, joint kinematics were expressed in two different ways. First, motion of the distal segment relative to the next proximal segment was examined because it has direct clinical relevance. Next, segmental kinematics were expressed relative to the global co-ordinate system to examine motion of each segment. Our results revealed minimal differences in tibial kinematics (Figure 3), highlighting changes in intrinsic foot function during gait in individuals with DM. Calcaneal pronation, manifest as calcaneal eversion (Figure 1-h, 2-h) and abduction (Figure 1-i, 2-i), was accompanied by first metatarsal (Figure 1b, 2b) and forefoot eversion in early stance (Figure 1e, 2e), supporting the argument that the foot is flexible and ‘splays’ during this interval. In subjects with DM, we found a reduction in the magnitude of peak calcaneal eversion and trends towards reduced abduction (Figure 1-h, 1-i, Table 4).

The reduction in calcaneal motion is important because subtalar pronation has important consequences on joints proximal, as well as distal to it. Subtalar motion reduces rotational stresses that would otherwise be transferred proximally [43]. Lack of eversion at the subtalar joint may be expected to render the axes of the transverse tarsal joints out of alignment thus decreasing the amount of motion possible though the midfoot for shock absorption [44, 45]. This phenomenon may help explain the reduced forefoot eversion (Figure 1e, 2e) noted in subjects with DM.

Loss of frontal plane mobility of the calcaneus may be attributed to several discrete yet coexisting processes in subjects with DM. While it is unlikely that subjects in either group approximated end range-of-motion of the subtalar joint [8, 13], increased stiffness of the subtalar joint as well as reduced compliance of the calcaneal heel pad [46] may contribute to reduced excursion. The reduction of joint excursion may also be ascribed to neuropathy. Previous studies [47, 48] have suggested that the absence of cutaneous feedback results in the adoption of a more conservative walking strategy. Reductions in forefoot motion may be due to lack of eversion of the subtalar joint but could also be due to factors intrinsic to the transverse tarsal joint, such as stiffness of talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints. In subjects with DM, non-enzymatic glycosylation of collagen may contribute to increased stiffness of the distal joints of the feet, hindering the ability of the foot to deform and transition from a rigid lever to a more flexible configuration.

Calcaneal motion, through its effect on the talonavicular joint may influence arch mobility. Gradual arch deformation, discerned as sagittal plane motion of the first metatarsal relative to the calcaneus (Figure 1-a) followed calcaneal pronation in both groups, in agreement with previous reports [20, 25, 30, 31]. In terminal stance, calcaneal plantarflexion, under the influence of the gastrocnemius-soleus complex, resulted in rapid tensing of the arch, providing midfoot stability. Particularly striking in both groups, was that medial longitudinal arch deformation was accompanied by nearly static first metatarsal inclination (Figure 2-a) supporting the theory that calcaneal mobility is a major contributor to arch motion while the first metatarsal provides distal stability. These data support the contention that the talus and calcaneus move over the relatively fixed naviculo-cuboid unit [39, 49].

Early calcaneal pronation was followed by gradual supination in both groups. These findings agree with the traditional understanding of foot mechanics wherein swing phase of the contralateral limb facilitates external rotation of the stance limb, which in turn helps initiate subtalar supination [40, 50]. Traditional foot models predict that forefoot pronation will accompany calcaneal supination in order for the sole of the foot to maintain contact with the ground. Consistent with this theory, our results showed that calcaneal supination was accompanied by the first metatarsal and forefoot staying static in eversion and abduction.

At terminal stance, in agreement with previous reports [18, 25, 30, 31, 51], calcaneal supination was accompanied by first metatarsal and forefoot supination to convert the foot into a rigid lever. In subjects with DM, decreases in calcaneal plantarflexion (Figure 1-g and 2-g), first metatarsal and forefoot supination were noted (Figures 1 and 2; e and h). Decreased calcaneal plantarflexion may result from reduced plantarflexor contraction at push off [52]. Decreases in first metatarsal and forefoot motion accentuate the finding that it takes less supination in the foot with DM to create a stable, rigid lever at push off. In subjects with DM, a greater proportion of midfoot stability may be derived from modified/stiffer soft tissue such as the plantar fascia [53].

In summary, we applied a multisegment kinematic foot model with established reliability and validity to examine segmental foot mobility in individuals with and without DM and neuropathy. Our findings agree with the traditional understanding of foot mechanics and shed new light on patterns and magnitude of motion during gait. Decreases in frontal plane calcaneal motion were accompanied by reduced midfoot mobility, discerned as reduced first metatarsal and forefoot motion. Our findings indicate that there are dramatic differences in foot function in early stance in shock absorption and in propulsion in terminal stance.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by the following grants: RO1 NR07721-03 and M01 RR00059 from the General Clinical Research Centers Program, NCRR, NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gordois A, et al. The health care costs of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the US. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(6):1790–1795. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price P. The diabetic foot: quality of life. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39 Suppl 2:S129–S131. doi: 10.1086/383274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller MJ, et al. Impact of achilles tendon lengthening on functional limitations and perceived disability in people with a neuropathic plantar ulcer. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(7):1559–1564. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.7.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saltzman CL, Nawoczenski DA. Complexities of foot architecture as a base of support. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;21(6):354–360. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1995.21.6.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarrafian SK. Functional characteristics of the foot and plantar aponeurosis under tibiotalar loading. Foot Ankle. 1987;8(1):4–18. doi: 10.1177/107110078700800103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arkkila PE, Kantola IM, Viikari JS. Limited joint mobility in non-insulin-dependent diabetic (NIDDM) patients: correlation to control of diabetes, atherosclerotic vascular disease, and other diabetic complications. J Diabetes Complications. 1997;11(4):208–217. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(96)00038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delbridge L, et al. Limited joint mobility in the diabetic foot: relationship to neuropathic ulceration. Diabet Med. 1988;5(4):333–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1988.tb01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffin AC, et al. Limited joint mobility in the hands and feet of adolescents with Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetic Medicine. 1999;16(2):125–130. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernando DJ, et al. Relationship of limited joint mobility to abnormal foot pressures and diabetic foot ulceration. Diabetes Care. 1991;14(1):8–11. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernando DJ, Vernidharan J. Limited joint mobility in Sri Lankan patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. British Journal of Rheumatology. 1997;36(3):374–376. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frost D, Beischer W. Limited joint mobility in type 1 diabetic patients: associations with microangiopathy and subclinical macroangiopathy are different in men and women. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(1):95–99. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glasoe WM, et al. Dorsal mobility and first ray stiffness in patients with diabetes mellitus. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25(8):550–555. doi: 10.1177/107110070402500807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller MJ, et al. Insensitivity, limited joint mobility, and plantar ulcers in patients with diabetes mellitus. Phys Ther. 1989;69(6):453–459. doi: 10.1093/ptj/69.6.453. discussion 459–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenbaum D, et al. Calcaneal fractures cause a lateral load shift in Chopart joint contact stress and plantar pressure pattern in vitro. J Biomech. 1996;29(11):1435–1443. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(96)84539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sammarco VJ. The talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints: anatomy, biomechanics, and clinical management of the transverse tarsal joint. Foot Ankle Clin. 2004;9(1):127–145. doi: 10.1016/S1083-7515(03)00152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birke JA, Franks BD, Foto JG. First ray joint limitation, pressure, and ulceration of the first metatarsal head in diabetes mellitus. Foot & Ankle International. 1995;16(5):277–284. doi: 10.1177/107110079501600506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glasoe WM, Yack HJ, Saltzman CL. Anatomy and biomechanics of the first ray. Phys Ther. 1999;79(9):854–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornwall MW, McPoil TG. Motion of the calcaneus, navicular, and first metatarsal during the stance phase of walking. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2002;92(2):67–76. doi: 10.7547/87507315-92-2-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornwall MW, McPoil TG. Three-dimensional movement of the foot during the stance phase of walking. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1999;89(2):56–66. doi: 10.7547/87507315-89-2-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacWilliams BA, Cowley M, Nicholson DE. Foot kinematics and kinetics during adolescent gait. Gait & Posture. 2003;17(3):214–224. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(02)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wearing SC, et al. Sagittal plane motion of the human arch during gait: a videofluoroscopic analysis. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19(11):738–742. doi: 10.1177/107110079801901105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilken J, et al. Understanding dynamic arch motion: A new paradigm. XXth Congress of the International Society of Biomechanics; Cleveland, OH. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen MK, et al. Relationship between static mobility of the first ray and first ray, midfoot, and hindfoot motion during gait. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25(6):391–396. doi: 10.1177/107110070402500605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nawoczenski DA, Baumhauer JF, Umberger BR. Relationship between clinical measurements and motion of the first metatarsophalangeal joint during gait. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery - American Volume. 1999;81(3):370–376. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199903000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leardini A, et al. An anatomically based protocol for the description of foot segment kinematics during gait. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 1999;14(8):528–536. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(99)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006;29 Suppl 1:S43–S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mueller MJ. Identifying patients with diabetes mellitus who are at risk for lower-extremity complications: use of Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments. Phys Ther. 1996;76(1):68–71. doi: 10.1093/ptj/76.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pham H, et al. Screening techniques to identify people at high risk for diabetic foot ulceration: a prospective multicenter trial. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(5):606–611. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.5.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilken J, Saltzman C, Yack H. Validation of a multi-segment foot model. Summer Meeting, American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society; Seattle, WA. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carson MC, et al. Kinematic analysis of a multi-segment foot model for research and clinical applications: a repeatability analysis. Journal of Biomechanics. 2001;34(10):1299–1307. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunt AE, et al. Inter-segment foot motion and ground reaction forces over the stance phase of walking. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2001;16(7):592–600. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott SH, Winter DA. Talocrural and talocalcaneal joint kinematics and kinetics during the stance phase of walking. J Biomech. 1991;24(8):743–752. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(91)90338-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piazza SJ. Mechanics of the subtalar joint and its function during walking. Foot Ankle Clin. 2005;10(3):425–442. v. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cavanagh PR, et al. The relationship of static foot structure to dynamic foot function. J Biomech. 1997;30(3):243–250. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(96)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saltzman CL, Nawoczenski DA, Talbot KD. Measurement of the medial longitudinal arch. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76(1):45–49. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilken J. Physical rehabilitation science. Iowa City: The University of Iowa; 2006. The effect of arch height on tri-planar foot kinemetics during gait; p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tome J, et al. Comparison of Foot Kinematics Between Subjects with Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction and Healthy Controls. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2006;36(9):635–644. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woltring H. Representation and calculation of 3D joint movement. Human Movement Science. 1991;10:603–616. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levangie PK, Norkin CC. Joint structure and function : a comprehensive analysis. 3rd. ed. Philadelpha: F.A. Davis; 2001. p. xv.p. 494. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the musculoskeletal system : foundations for physical rehabilitation. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002. p. xxii.p. 597. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunt AE, Fahey AJ, Smith RM. Static measures of calcaneal deviation and arch angle as predictors of rearfoot motion during walking. Aust J Physiother. 2000;46(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westblad P, et al. Differences in ankle-joint complex motion during the stance phase of walking as measured by superficial and bone-anchored markers. Foot & Ankle International. 2002;23(9):856–863. doi: 10.1177/107110070202300914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perry J. Anatomy and biomechanics of the hindfoot. Clin Orthop. 1983;(177):9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elftman H. Dynamic structure of the human foot. Artif Limbs. 1969;13(1):49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blackwood CB, et al. The midtarsal joint locking mechanism. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26(12):1074–1080. doi: 10.1177/107110070502601213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kao PF, Davis BL, Hardy PA. Characterization of the calcaneal fat pad in diabetic and non-diabetic patients using magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;17(6):851–857. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(99)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nurse MA, Nigg BM. The effect of changes in foot sensation on plantar pressure and muscle activity. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2001;16(9):719–727. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giacomozzi C, et al. Walking strategy in diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(8):1451–1457. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.8.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilken J. PhD Thesis. University of Iowa; 2006. Triplanar motion of the foot. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inman VT. Human locomotion. 1966. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(288):3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arndt A, et al. Ankle and subtalar kinematics measured with intracortical pins during the stance phase of walking. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25(5):357–364. doi: 10.1177/107110070402500514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maluf KS, et al. Tendon Achilles lengthening for the treatment of neuropathic ulcers causes a temporary reduction in forefoot pressure associated with changes in plantar flexor power rather than ankle motion during gait. J Biomech. 2004;37(6):897–906. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giacomozzi C, et al. Does the thickening of Achilles tendon and plantar fascia contribute to the alteration of diabetic foot loading? Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2005;20(5):532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]