Abstract

Evidence from Drosophila and cultured cell studies support a role for heterotrimeric G proteins in Wnt signaling. Wnt inhibits the degradation of the transcriptional regulator β-catenin. We screened the α subunits of major families of recombinant G protein subunits and Gβγ subunits in a Xenopus egg extract system that reconstitutes β-catenin degradation. We found that Gαo, Gαq, Gαi2, and Gβγ inhibited β-catenin degradation. Gβ1γ2 promoted phosphorylation and activation of the Wnt co-receptor low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6) by recruiting synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) to the membrane and enhancing its kinase activity. In both a reporter gene assay and an in vivo assay, c-βARK, an inhibitor of Gβγ, blocked LRP6 activity. Several components of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway formed a complex: Gβ1γ2, LRP6, GSK3, axin, and dishevelled. We propose that heterotrimeric G protein activation results in formation of free Gβγ and Gα, which act cooperatively to inhibit β-catenin degradation and activate β-catenin-mediated transcription.

INTRODUCTION

Heterotrimeric G proteins, which consist of a Gα subunit and an associated Gβγ dimer, mediate a multitude of physiological responses from a host of diverse ligands. Activated G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) catalyze the exchange of GDP for GTP on Gα, resulting in subunit dissociation and G protein activation. The signal is terminated upon hydrolysis of GTP by Gα by the intrinsic guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) activity of the Gα subunit and its subsequent reassociation with Gβγ. Both Gα and Gβγ activate many downstream effectors.

The pathway from the ligand Wnt to the transcriptional regulator β-catenin (Wnt/β-catenin pathway) is conserved throughout metazoa and required for coordination of diverse developmental programs, stem cell maintenance, and cell growth and proliferation. In the absence of the Wnt ligand, the cytoplasmic β-catenin concentrations are kept low by the destruction complex, which is composed of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), axin, and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3). GSK3 phosphorylates β-catenin, thereby marking it for ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation. Binding of Wnt to the co-receptors Frizzled and low density lipoprotein receptor-related Protein 6 (LRP6), a single transmembrane domain protein, inhibits β-catenin destruction, allowing cytoplasmic β-catenin concentrations to increase. β-catenin enters the nucleus to initiate a transcriptional program with T cell factor and lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) family members [1]. The initial discovery that the Wnt receptor, Frizzled, contains seven predicted transmembrane domains, a topology characteristic of GPCRs, suggested that Frizzled signals through heterotrimeric G proteins, although direct evidence for coupling between Frizzled and G proteins is lacking [1]. Activation of the transcriptional activity of β-catenin (the β-catenin/TCF pathway), however, has been reported to occur through GPCRs independent of Wnt and Frizzled. Signaling through the gonadotrophin-releasing hormone receptor [2], prostaglandin receptor [3], or parathyroid receptor [4] activates the transcriptional activity of β-catenin.

During Wnt signaling, activation of LRP6 depends on phosphorylation of conserved motifs within its intracellular domain [5, 6]. A pool of axin-bound GSK3 that translocates to the membrane through a process involving dishevelled (Dsh) may contribute to the initial phosphorylation of LRP6 at the plasma membrane [6, 7]. Phosphorylated LRP6 provides additional docking sites for cytoplasmic axin-GSK3 complexes to promote further phosphorylation of LRP6. Binding of the axin-GSK3 complex to phosphorylated LRP6 inhibits GSK3, leading to a subsequent decrease in β-catenin phosphorylation [8-10]. Thus, GSK3 in the destruction complex promotes β-catenin degradation, whereas GSK3-mediated phosphorylation of LRP6 at the plasma membrane contributes to stabilization of β-catenin; thus both GSK3 activity and inhibition of its activity are required for LRP6-mediated β-catenin stabilization. Additionally, LRP6 is also a substrate for and an inhibitor of GSK3. We provide evidence that Gβγ recruits GSK3 to the plasma membrane, thereby promoting its activity toward LRP6, which places Gβγ in a pivotal role in the initiation of LRP6 activation.

RESULTS

Biochemical screen identifies G proteins that regulate β-catenin turnover

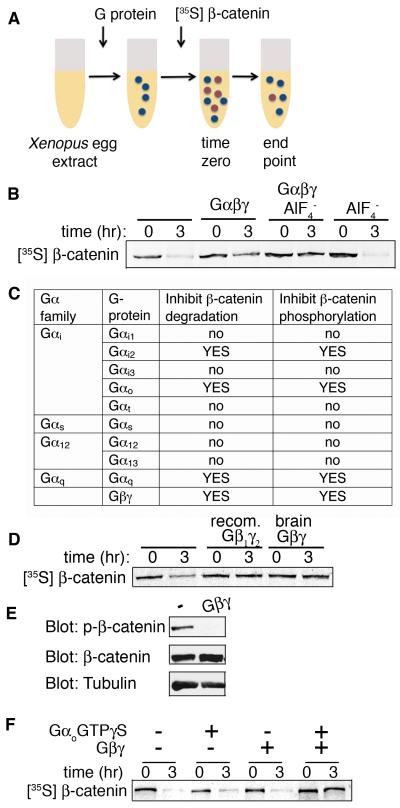

The Xenopus egg extract system recapitulates numerous complex GTP-dependent phenomena, such as microtubule dynamics, translation, DNA replication, nuclear envelope reformation, and mitotic spindle assembly [11-13]. It contains cytosol and other cellular components, including plasma membrane, organelles, amino acids, and nucleotides at or near physiological levels (Fig. S1) [14]. Furthermore, this system contains the components of the Wnt pathway responsible for the regulation and degradation of β-catenin and thus can be used to recapitulate β-catenin regulation by monitoring the abundance of exogenous [35S]β-catenin or endogenous β-catenin phosphorylation in the presence of additional factors [15]. To assess whether Xenopus egg extract could be used to test the role of G proteins in regulating β-catenin stability, we used purified G protein heterotrimers (primarily Go) from brain for reconstitution [16] (Fig. 1A). We detected modest inhibition of [35S]β-catenin degradation upon addition of the G protein heterotrimer (Fig. 1B), with greater inhibition upon G protein activation (and disassociation into the active subunits α and βγ) by AlF4−. Partial activity of the heterotrimer in the absence of AlF4− may have resulted from partial activation of the heterotrimer due to nucleotide exchange (GDP for GTP) of Go within the crude egg extract, which contains high concentrations of GTP [12, 14].

Fig. 1.

G proteins inhibit β-catenin degradation in a Xenopus egg extract system. (A) Schematic of assay used to assess the effects of G protein subunits on in vitro translated (IVT) [35S] β-catenin degradation in Xenopus egg extract. (B) Addition of purified brain G protein (5 μM) inhibits degradation of radiolabeled (IVT) [35S] β-catenin in Xenopus egg extract and inhibition is potentiated by the G protein activator AlF4−. (C) In the Xenopus egg extract system, the activities of the major classes of G proteins subunits on IVT [35S]β-catenin turnover and phosphorylation of endogenous β-catenin at GSK3 consensus sites vary (see Fig. S2 for details). (D) Both recombinant Gβ1γ2 (recom., 5 μM) and brain Gβγ (5 μM) inhibit β-catenin degradation. (E) Addition of brain Gβγ (5 μM) to Xenopus egg extract inhibits phosphorylation of endogenous β-catenin at GSK3 consensus sites (Ser33/Ser37/Thr41). Extract was analyzed after 2 hr incubation. Tubulin is loading control. (F) Gβ1γ2 synergizes with GαoA to inhibit β-catenin degradation. [35S]β-catenin was added to Xenopus egg extract and incubated with buffer, Gβ1γ2 (0.5 μM), GαoA-GTPγS (0.25 μM), or Gβ1γ2 (0.5 μM) plus GαoA-GTPγS (0.25 μM). Gβ1γ2 and GαoA-GTPγS were added at sub-threshold concentrations such that they did not inhibit β-catenin degradation on their own. Figures are representative of experiments performed three times.

To identify G proteins involved in regulating β-catenin stability, we tested the four major classes of Gα subunits for their capacity to inhibit degradation of [35S]β-catenin in the Xenopus egg extract (Fig. 1A,C). The specificity of each G protein in inhibiting β-catenin degradation was also assessed by immunoblotting for endogenous β-catenin phosphorylation by GSK3 (Fig. 1C; Fig. S2B). Both inactive (GDP-bound) and active forms were tested. For activation, proteins were bound to a GTPγS analog or, for Gαt and Gαq, which exhibit slow nucleotide exchange in the absence of receptor activation, were treated with GDP-AlF4−. We found that, in addition to the previously implicated Gαo [17, 18] and Gαq [19, 20], Gαi2 also inhibited exogenous β-catenin degradation and phosphorylation of endogenous β-catenin by GSK3. β-catenin was stabilized in egg extract when the GDP-bound forms of Gαo and Gαi2, but that of not Gαq, were added to the extract. This is likely due to differences in affinity for GTP and the rates of nucleotide exchange between Gα subunits (GDP dissociation rate of Gαo = 0.19 min−1 at 30°C; GDP dissociation rate of Gαi2 = 0.07 min−1 at 30°C; Gαq has very low affinity for GTP in the absence of receptor) [21, 22]. Gβγ protein purified from brain, as well as recombinant Gβ1γ2, inhibited β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation (Fig. 1D,E; Fig. S3). Additionally, Gβγ synergized with Gαo to inhibit β-catenin degradation, suggesting that Gαo and Gβγ act cooperatively (Fig. 1F).

The effective concentrations of Gα and Gβγ that we used in the Xenopus egg extract system are in the low micromolar range, well below the predicted concentrations of heterotrimeric G proteins at the plasma membrane (~1 mM) [23]. Furthermore, because membrane localization of G proteins is not homogeneous, local concentrations of G proteins within the plasma membrane may actually exceed 1 mM [23]. The micromolar concentrations of Gα and Gβγ required to inhibit β-catenin degradation in the Xenopus egg extract system may also reflect the presence of competing binding proteins for Gα and Gβγ. For example, the concentration of tubulin in the Xenopus egg extract has been estimated as ~24 μM (4.1% of total protein), and the Xenopus egg extract contains an abundance of microtubules [24]. Microtubules bind Gβγ [25] and thus, are likely to compete with β-catenin regulatory components for Gβγ binding.

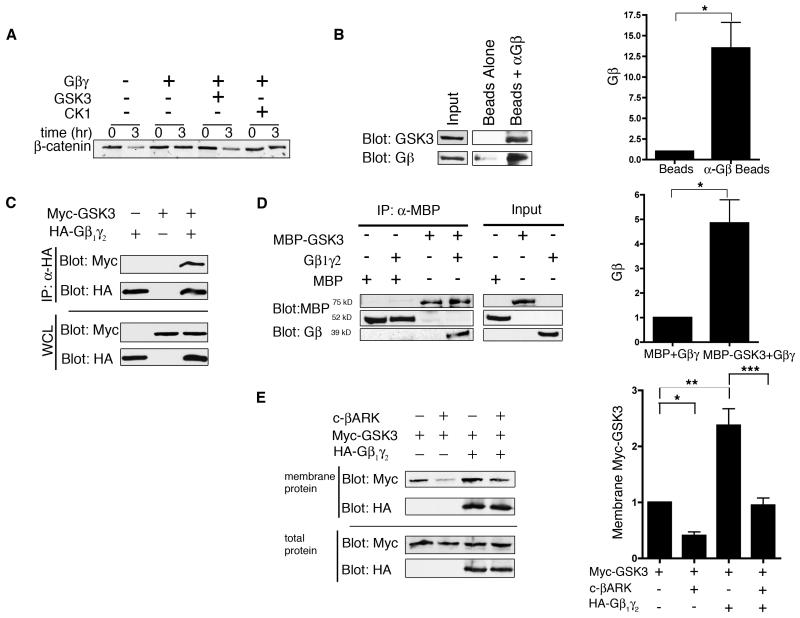

Gβγ binds and recruits GSK3 to the membrane

We hypothesized that the mechanism by which Gβγ inhibits β-catenin degradation in the egg extract involves sequestration of GSK3 at membranes, thereby preventing phosphorylation of cytoplasmic β-catenin. Isoprenylation of Gγ targets Gβγ subunits to the plasma membrane. Thus, Gβγ added to the Xenopus egg extract, which contains membranous organelles, is likely incorporated into membranes. Furthermore, when Gβγ interacts with any of three of its kinase effectors [G protein coupled-receptor kinase 2 (GRK2), Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK), and phosphoinositide 3 kinase γ (PI3Kγ)] these become translocated to the membrane [26]. In support of the hypothesis that Gβγ interacts with GSK3, addition of GSK3 (but not casein kinase I) to the extract reversed the inhibitory effects of Gβγ on β-catenin degradation (Fig. 2A). Interaction with free Gβγ subunit likely sequesters cytoplasmic GSK3 to the membrane pool in the Xenopus egg extract because AlF4−-activated (but not the unactivated) brain G protein shifted the endogenous GSK3 pool to the membrane fraction (Fig. S4). To confirm an interaction between GSK3 and Gβγ, we showed that endogenous GSK3 co-immunoprecipitated with endogenous Gβγ from the extract (Fig. 2B). When co-expressed in cultured mammalian cells, Myc-tagged GSK3 similarly co-immunoprecipitated with hemaglutinin (HA)-tagged Gβ1γ2 (Fig. 2C). In contrast, we were unable to demonstrate co-immunoprecipitation of GSK3 and Gαo when both were co-expressed in cultured mammalian cells (Fig. S5). We also observed an interaction between purified Gβγ and GSK3 (Fig. 2D), suggesting that GSK3 and Gβγ directly interact.

Fig. 2.

Gβ1γ2 binds and promotes GSK3 membrane localization. (A) Addition of GSK3 blocked the ability of Gβ1γ2 to inhibit β-catenin degradation in Xenopus egg extract. [35S] β-catenin was added to extract and incubated with Gβ1γ2 (5 μM), Gβ1γ2 plus GSK3 (10 units/μl), or Gβ1γ2 plus CKI (100 units/μl). (B) GSK3 co-immunoprecipitates with Gβ from Xenopus egg extract. Beads coupled to anti-Gβ antibody were incubated with extract, washed, eluted with sample buffer, and immunoblotted for Gβ and GSK3. Representative blot is shown on left; quantitation on right (*P<0.005, n ≥ 3, t-test,). (C) GSK3 co-immunoprecipitates with Gβ1γ2 from cultured cells. HEK-293 cells were transfected with Myc-GSK3 and HA-Gβ1γ2, lysed, immunoprecipitated with an antibody against HA, and Myc-GSK3 was detected by immunoblotting for Myc. (D) Purified GSK3 binds recombinant Gβ1γ2 in vitro. GSK3 fused to (MBP-GSK3, 0.66 μM) or MBP (0.66 μM) was incubated with Gβ1γ2 (0.6 μM) and proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-MBP antibody. Samples were washed, eluted, and immunoblotted for Gβ and MBP. Representative blot is shown on left; quantitation on right (*P<0.005, n ≥ 3, t-test). (E) Gβ1γ2 enhances association of GSK3 with membrane fractions, and this effect is reversed by c-βARK. HeLa cells were transfected with c-βARK, Myc-GSK3, and HA-Gβ1γ2. Cell membranes were isolated and immunoblotted for Myc and HA. Representative blot is shown on left; quantitation on right (*, **, *** P<0.005, n ≥ 3, t-test)

To test whether the interaction between Gβγ and GSK3 promoted membrane localization of GSK3, we expressed Myc-GSK3 with or without HA-Gβ1γ2 in HeLa cells and isolated membrane-associated proteins. An increased fraction of GSK3 was membrane-associated when Gβ1γ2 was co-expressed (Fig. 2E). Because cellular knockdown of Gβγ is complicated by subsequent loss of Gα signaling [27, 28], we used the C-terminal domain of β-adrenergic receptor kinase (c-βARK) to bind and inhibit free Gβγ [29]. Inhibition of both HA-Gβ1γ2 and endogenous Gβγ by c-βARK reduced the membrane localization of Myc-GSK3 (Fig. 2E).

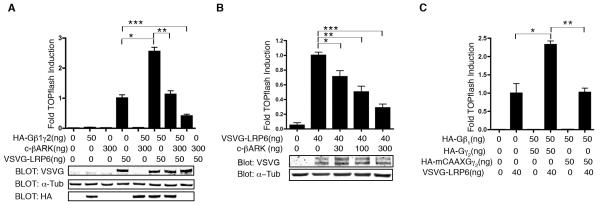

Gβγ is required for maximal LRP6 stimulation of β-catenin transcriptional activity

By promoting membrane localization of GSK3, Gβ1γ2 could enhance the activity of GSK3 towards membrane-localized substrates, such as LRP6. To monitor LRP6-mediated signaling, we analyzed HEK 293 Super TOPflash (STF) cells (HEK 293 cells stably transformed with the Wnt reporter construct TOPflash) expressing LRP6 fused to the vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSVG-LRP6), which results in constitutive activation of β-catenin/TCF-mediated transcription [30], quantified as activity of the TOPflash reporter. HA-Gβ1γ2 enhanced VSVG-LRP6-stimulated TOPflash activity and this was blocked by co-expression of c-βARK (Fig. 3A, B). Consistent with the importance of Gβ1γ2 membrane localization for its enhancement of LRP6 activity, overexpression of a Gγ2 CAAX mutant lacking the isoprenylation modification (required for Gγ membrane localization) failed to enhance VSVG-LRP6-stimulated TOPflash activity (Fig. 3C). We also noted that c-βARK alone decreased TOPflash activation by VSVG-LRP6 (Fig. 3A,B), suggesting that endogenous Gβγ contributes to LRP6 signaling. To confirm that c-βARK was not affecting other components of the β-catenin pathway, we showed that c-βARK did not coimmunoprecipitate with axin, GSK3, or Dsh (Fig. S6).

Fig. 3.

LRP6 activation of β-catenin/TCF signaling is regulated by Gβ1γ2. (A) Gβ1γ2 enhances LRP6 stimulation of TOPflash, and c-βARK inhibits the effects of Gβ1γ2 on LRP6 activity. HEK-293 STF cells were transfected with various combinations of HA-Gβ1γ2, VSVG-LRP6, and c-βARK. Lysates were assayed by TOPflash and immunoblotting and quantified [ANOVA (family-wise), *P=8.38×10−13, **P=3.35×10−12, ***P=1.09×10−6]. Tubulin (tub) served as the loading control (B) VSVG-LRP6 activation was inhibited by c-βARK. HEK-293 STF cells were transfected with VSVG-LRP6 plus increasing amounts of plasmid encoding c-βARK. Lysates were assayed by TOPflash and immunoblotting and quantified [ANOVA (family-wise), *P=0.001, **P=9.94×10−6, ***P=3.41×10−7]. (C) Membrane localization of Gβ1γ2 is required for it to enhance LRP6 activity. In contrast to wild-type Gγ2, expression of a Gγ2 CAAX mutant (lacking a signal for isoprenylation) did not enhance LRP6 activity as assessed by TOPflash [ANOVA, (family-wise),*P= 4.12×10−7, **P=6.81×10−7]. The amount of plasmid transfected is indicated. Luciferase activity is fold-induction compared to VSVG-LRP6 alone (mean ± s.d.). Experiments were performed in triplicate.

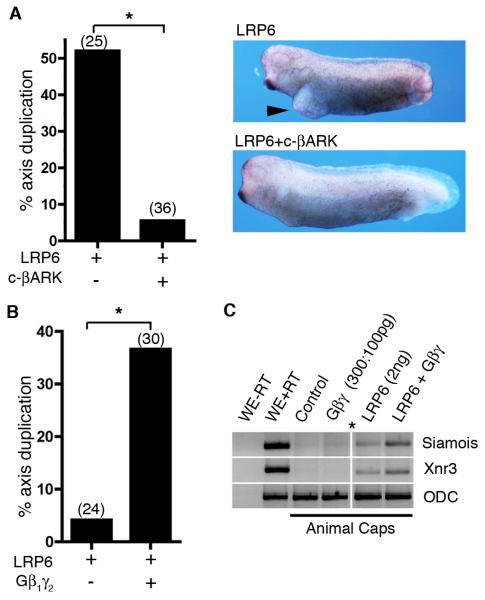

To provide in vivo evidence that the interaction between Gβγ and LRP6 occurs, we investigated their interactions in Xenopus laevis embryos and ectodermal explants. Ectopic activation of the β-catenin/TCF pathway in ventral blastomeres (for example by injection of LRP6-encoding mRNA) induces formation of a partial ectopic axis in Xenopus embryos [31]. We found that coinjection of mRNA for LPR6 with mRNA encoding c-βARK inhibited secondary axis formation (Fig. 4A). In contrast, coinjection of mRNAs for LRP6 and Gβ1γ2 promoted axis duplication in Xenopus embryos (Fig. 4B) and expression of the Wnt target genes, Siamois and Xnr3, in Xenopus ectodermal explant (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Gβγ enhances LRP6 activation of β-catenin signaling in vivo (A) Secondary axis formation by injection of LRP6 mRNA (2 ng) into one ventral blastomere of 4-cell Xenopus embryos is inhibited by coinjection of c-βARK RNA (1 ng). Arrow head marks secondary axis. Frequency of axis duplication is plotted (Fisher’s exact test, *P<0.0001). (B) Coinjecting Gβ1γ2 mRNA (0.5 ng) enhanced LRP6-stimulated (1 ng) secondary axis formation (Fisher’s exact test, *P=0.004). Injection of cβARK mRNA (n=31) or Gβ1γ2 mRNA (n=27) alone into ventral blastomere did not perturb axis formation. (C) Coinjection of LRP6 mRNA (0.5 ng) and Gβ1γ2 mRNA (0.5 ng) promotes ectopic transcription of Wnt/β-catenin targets genes, Xnr3 and Siamois, in ectopic explants (animal caps) to a greater extent than injection of LRP6 alone as assayed by RT-PCR. WE, whole embryos; Caps, animal caps; WE-RT, no reverse transcriptase added; ODC, ornithine decarboxylase (loading control). Asterisk marks intervening lanes that were removed.

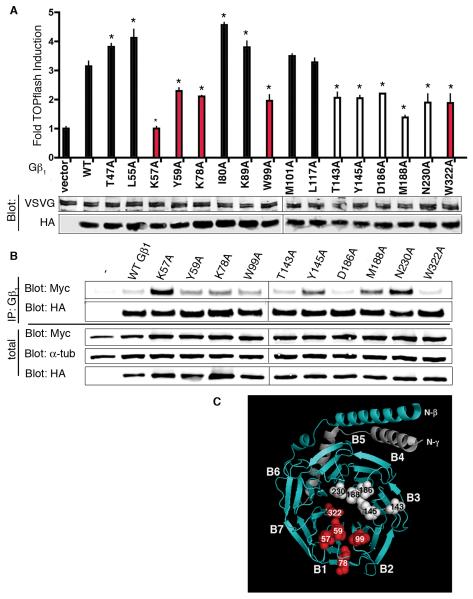

Residues clustered on blades 1, 3, and 4 of Gβ1 are involved in GSK3 binding and stimulation of LRP6 activity

Previous studies identified critical residues on Gβ1 that mediate its interaction with specific effectors [32, 33]. To determine whether these sites also mediate GSK3 binding, LRP6 activation, or both, we generated a series of single alanine mutants of Gβ1, of which a subset exhibited a decreased capacity to activate LRP6, reflected as decreased stimulation of the TOPflash reporter in VSVG-LRP-expressing cells (Fig. 5A). Gβ is a WD40-repeat protein that forms a seven-bladed β-propeller structure [26]. Based on previous X-ray crystal structures of Gβ, residues altered in this subset of mutants are clustered within two regions of Gβ1, predominantly within blades 1, 3, and 4 (Fig. 5C). For the subset of Gβ1 mutants with impaired LRP6 activation, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments to test the capacity of each mutant to bind GSK3. Several of these Gβ1 mutants bound GSK3 more avidly than did wild-type Gβ1 (Fig. 5B). These results support a model in which a dynamic interaction between Gβγ and GSK3 is required to promote LRP6 activation.

Fig. 5.

Scanning alanine mutagenesis of Gβ1 identifies amino acids that mediate LRP6 activation and GSK3 interaction. (A) Mutagenesis of Gβ1 reveals specific amino acids required for enhancement of LRP6 activity measured by TOPflash. VSVG-LRP6 (40 ng) was transfected alone or with the indicated Gβ1 mutant (50 ng) plus Gγ2 (50 ng) into HEK-293 STF cells. Lysates were assayed by TOPflash and immunoblotting (anti-HA for HA-Gβ1 and anti-VSVG for VSVG-LRP6). Red and white bars represent mutants that map to two clusters on the surface of Gβ1. For TOPflash assays, experiments were performed in triplicate, and luciferase activity is fold induction compared to LRP6 (mean ± s.d.) [ANOVA (family-wise), *P<0.005]. (B) Co-immunoprecipitation of GSK3 with Gβ1 point mutants. HEK-293 cells were transfected with Myc-GSK3, HA-Gβ1 point mutants, and Gγ2. Cells were lysed, HA-Gβ1 immunoprecipitated, and Myc-GSK3 was detected by immunoblotting. Each experiment was repeated three times with representative results are shown. (C) The crystal coordinates of Gβ1γ2 (PDB 1XHM). Gβ1 is shown in teal and Gγ2 in gray. The seven β-propellers of Gβ are labeled B1-B7. Two clusters of amino acids required for Gβ1-enhancement of LRP6 activity are in red and white.

Gβγ and Dsh are both needed to for maximal stimulation of β-catenin transcriptional activity

To investigate what effect Gβ1γ2 had in Wnt-mediated activation of β-catenin signaling, we analyzed the effects of overexpression of HA-Gβ1γ2 or inhibition of Gβ1γ2 with c-βARK in cultured cells exposed to Wnt3a. HA-Gβ1γ2 did not affect Wnt3a-stimulated TOPflash activity in cultured HEK 293 STF cells, which contain the TOPflash reporter and endogenously express Frizzled and LRP6 receptors (Fig. S7A). The presence of c-βARK also had no effect on Wnt3a-stimulated activity (Fig. S7B). This may suggest that, similar to CK1γ, Gβ1γ2 becomes limiting only when LRP6 is present in excess [5]. Alternatively, Gβγ may be activated through Wnt-independent pathways to signal through a distinct mechanism upstream of LRP6.

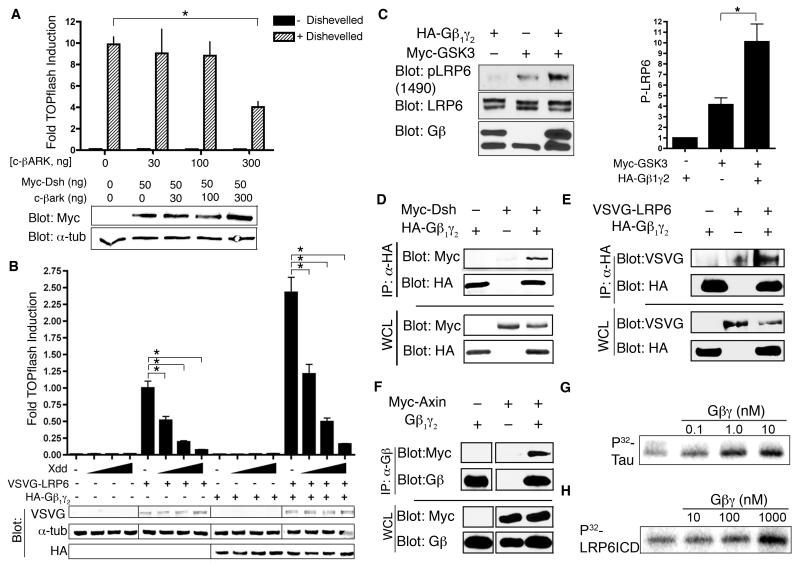

We investigated at what point Gβγ functioned in the β-catenin pathway. Dsh acts downstream of Frizzled and upstream or at the level of the β-catenin degradation complex in the Wnt pathway and is required for LRP6 phosphorylation [34]. Similar to LRP6, excess Dsh activates β-catenin/TCF signaling in the absence of other stimuli [35]. In HEK 293 STF cells that are overexpressing Dsh, β-catenin is stabilized in the absence of ligand and the TOPflash reporter is expressed. Cells coexpressing c-βARK and Dsh exhibited less TOPflash activity than did cells only expressing Dsh (Fig. 6A), indicating a requirement of Gβγ for Dsh to activate β-catenin signaling. Introduction of a dominant-negative mutant of Dsh (Xdd) [36] with VSVG-LRP6 and Gβ1γ2 into the HEK 293 STF cells prevented Gβ1γ2 from enhancing the activity of the TOPflash reporter (Fig. 6B). Xdd also inhibited activation of TOPflash by LRP6 alone (Fig. 6B), consistent with a role for Dsh in mediating LRP6 activation [7, 34]. These studies suggest that both Gβγ and Dsh contribute to LRP6 activation. There was no detectable effect of HA-Gβ1γ2 or c-βARK when the pathway was stimulated by LiCl, a GSK3 inhibitor, confirming that Gβγ acts upstream of the β-catenin destruction complex (Fig. S7C,D). These data suggest that Gβγ functions upstream of the destruction complex at the level of LRP6 and Dsh.

Fig. 6.

Gβ1γ2 promotes Dsh-mediated activation of β-catenin signaling and enhances phosphorylation of LRP6 by GSK3. (A) HEK-293 STF cells were transfected with Myc-Dsh plus increasing amounts of plasmid encoding c-βARK. Transfected cells were then lysed and processed for TOPflash or immunoblotting [mean ± s.d., ANOVA (family-wise), *P=3.85×10−5]. (B) Dsh is required for LRP6-mediated TOPflash activation. Dominant-negative Dsh (Xdd; 20 ng, 50 ng, 125 ng) inhibited LRP6 (40 ng) activation of TOPflash, and Gβ1γ2 (50 ng each) enhanced LRP6 activation of TOPflash in HEK-293 STF cells [mean ± s.d., ANOVA (family-wise), *P=0.0009]. (C) Gβ1γ2 increases phosphorylation of endogenous LRP6 when co-transfected with GSK3. HEK-293 cells were transfected with Myc-GSK3 with or without HA-Gβ1γ2 and lysates immunoblotted with anti-phospho-LRP6 (Ser1490) antibody. Representative blot shown on left, quantification on right (3 experiments, t-test,*P<0.005). (D) Dsh co-immunoprecipitates with Gβ1γ2 from cultured cells. HEK-293 cells were transfected with HA-Gβ1 (1 μg), Gγ2 (1 μg), and Myc-Dsh (1 μg). Cells were lysed, HA-Gβ1 immunoprecipitated, and Myc-Dsh was detected by immunoblotting for the Myc tag. (E) LRP6 co-immunoprecipitates with Gβ1γ2 from cultured cells. Membrane proteins were isolated from HEK-293 cells transfected with HA-Gβ1 (1 μg), Gγ2 (1 μg), and VSVG-LRP6 (1 μg). HA-Gβ1 was immunoprecipitated and VSVG-LRP6 detected by immunoblotting for the VSVG tag. (F) Axin co-immunoprecipitates with Gβ1γ2 from cultured cells. HEK-293 cells were transfected with Gβ1 (1 μg), Gγ2 (1 μg), and Myc-Axin (1 μg). Cells were lysed, Gβ1 immunoprecipitated, and Myc-Axin was detected by immunoblotting for the Myc tag. (G,H) Gβ1γ2 enhances GSK3 phosphorylation of Tau (F) and LRP6ICD (G) in vitro. Each experiment was repeated three times with representative results shown.

Gβγ enhances LRP6 phosphorylation by GSK3

To further the mechanism by which Gβ1γ2 enhances LRP6 signaling, we transfected cells with Gβ1γ2 and GSK3, isolated membrane-associated proteins, and immunoblotted with an antibody that recognizes LRP6 phosphorylated at sites that could be phosphorylated by GSK3. When GSK3 was co-expressed with Gβ1γ2, there was an increase in phosphorylated LRP6 above that observed when GSK3 was expressed alone (Fig. 6C). Gβ1γ2 coimmunoprecipitated with several proteins involved in β-catenin regulation: Dsh (Fig. 6D), LRP6 (Fig. 6E), axin (Fig. 6F), and GSK3 (Fig. 2C). These results are consistent with previous reports of coimmunoprecipitation of Gβ1γ2 with axin [37] and with Dsh [37-39]. Thus, Gβγ appears to act in a complex with Dsh, axin, and GSK3 to promote phosphorylation of LRP6.

In vitro kinase assays showed that Gβγ enhanced GSK3 phosphorylation of Tau, a GSK3 substrate, whereas addition of either heterotrimeric Go or bovine serum albumin (BSA) did not enhance GSK3 activity towards Tau (Fig. 6G; Fig. S8A-C). Gβγ also enhanced GSK3 phosphorylation of the intracellular domain of LRP6 (LRP6ICD) on the PPPSP motif, which is required for LRP6 activity and provides a docking site for axin (Fig. 6H; Fig. S8D). Higher concentrations of Gβγ were required to stimulate GSK3 phosphorylation of LRP6ICD relative to required to stimulate Tau phosphorylation (Fig. 6G, H). This may reflect differences in the affinity of GSK3 for Tau versus LRP6ICD and a previously reported feedback mechanism by which phosphorylated LRP6 inhibits GSK3 activity [8-10]. Alternatively, LRP6 could simply compete with Gβγ for binding to GSK3. This latter model is consistent with our observation that Gβ1 mutants with increased affinity for GSK3 failed to activate β-catenin/TCF signaling.

DISCUSSION

With this report, GSK3 becomes the fourth identified Gβγ kinase effector (in addition to GRK2, BTK, and PI3Kγ) [26]. In each case, the mechanism of action of Gβγ appears to involve membrane translocation and, in the cases of PI3Kγ, BTK, and GSK3, stimulation of kinase activity. During zebrafish gastrulation, regulation of GSK3 by Gβγ plays a critical role in controlling the stability of the GSK3 substrate Snail [40]. Thus, Gβγ may control diverse signaling pathways through regulation of GSK3.

Gβγ has been reported to both negatively and positively influence Wnt signaling. Gβ2γ2 has been reported to negatively regulate Wnt1 signaling by a feedback mechanism that stimulates the degradation of Dsh in HEK 293T cells [37]; whereas a study in Drosophila indicated that Gβγ enhances β-catenin/TCF signaling [39, 41]. Knockdown of Gβ by RNAi during Drosophila wing development results in malformation of wing structures consistent with downregulation of Wg, the Drosophila ortholog of Wnt, signaling, and downregulation of Gβ reduced expression of Wg target genes in wing imaginal discs [39, 41]. In accord with our study, the authors did not observe ectopic activation of the Wg pathway when Gβγ was overexpressed. Together, our experiments with Xenopus embryos (Fig. 4) and the previous study with Drosophila [39, 41] provides evidence that Gβγ plays a positive role in β-catenin/TCF signaling in vivo.

The simplest model to explain the activation of β-catenin/TCF signaling by Gβγ would invoke a receptor-mediated mechanism. In contrast to its effects on Dsh and LRP6, however, c-βARK did not inhibit Wnt3a activation of β-catenin/TCF signaling. One possibility is that receptor-mediated activation of the heterotrimer and subsequent association of Gβγ and GSK3 is a rapid and tightly coupled process. Indeed, there is evidence that certain GPCRs and their G proteins remain tightly associated upon activation by ligand [41]. Thus, overexpression of c-βARK, which binds free Gβγ, may not be sufficient to disrupt Frizzled receptor-associated Gβγ. Alternatively, signaling through Gβ1γ2 may be independent of Wnt activation of Frizzled. Various GPCRs have been reported to activate β-catenin/TCF signaling. For example, the parathyroid receptor I activates LRP6 to stimulate β-catenin/TCF-mediated transcription, and the gonadotrophin-releasing hormone receptor inhibits GSK3 activity and stimulates β-catenin/TCF-mediated transcription [2, 4]. It remains to be determined whether Gβγ mediates β-catenin signaling through Frizzled or another GPCR.

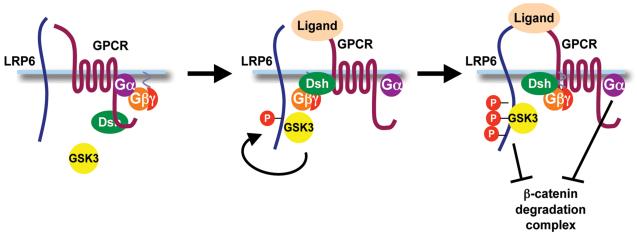

We propose a model in which both Gα and Gβγ regulate β-catenin/TCF signaling (Fig. 7). Analysis of purified recombinant proteins in the Xenopus egg extract system demonstrated a role for Gαo and Gαq, as well as Gαi2, in the inhibition of β-catenin degradation (Fig. 1). Additionally, our biochemical studies, in vivo assays, and experiments with cultured mammalian cells support a positive role for Gβγ in β-catenin/TCF signaling. Artificially tethering GSK3 to the plasma membrane is sufficient to stimulate Wnt signaling in cultured mammalian cells and axis duplication in Xenopus laevis embryos; thus, the β-catenin/TCF pathway appears to be very sensitive to GSK3 membrane localization [6]. Our data support a model in which Gβγ acts in concert with Dsh to recruit and activate GSK3 (either free or possibly in association with axin) at the plasma membrane; membrane-associated GSK3 phosphorylates LRP6, which then inhibits the β-catenin degradation complex to stabilize β-catenin, allowing β-catenin to translocate to the nucleus and mediate transcription.

Fig. 7.

Model for regulation of β-catenin/TCF signaling by Gα and Gβγ. Receptor activation dissociates Gα and Gβγ. Gβγ, along with Dsh, recruits and activates GSK3 (either free or possibly in association with axin) at the plasma membrane such that GSK3 can then phosphorylate and activate LRP6. Signaling downstream of the activated LRP6 receptor and Gα signaling events inhibit the β-catenin degradation complex, inhibiting β-catenin turnover. It is unclear whether the receptor is a classical GPCR or whether Frizzled is involved in transduction of the signal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constructs and purified proteins

Human Gβ1 was subcloned into pCS2-HA vector. hGβ1 alanine mutations were constructed with the QuikChange site mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) following the manufacturer’s protocol (Primer sequences: T47A F 5′-agaatccaaatgcgcgcgaggaggacactgc, R 5′-gcagtgtcctcctcgcgcgcatttggattct; L55A F 5′-cactgcgggggcacgcggccaagatctacg, R 5′-cgtagatcttggccgcgtgcccccgcagtg; K57A F 5′-gggggcacctggccgcgatctacgccatgc, R 5′-gcatggcgtagatcgcggccaggtgccccc; Y59A F 5′-cacctggccaagatcgccgccatgcactgggg, R 5′-ccccagtgcatggcggcgatcttggccaggtg; K78A F 5′-gtcagtgcctcgcaggatggtgcacttatcatctgggac, R 5′-gtcccagatgataagtgcaccatcctgcgaggcactgac; M80A F 5′-tgcctcgcaggatggtaaacttgccatctgggacagcta, R 5′tgcctcgcaggatggtaaacttgccatctgggacagcta; K89A F 5′-agctacaccaccaacgcggtccacgccatccc, R 5′-gggatggcgtggaccgcgttggtggtgtagct; W99A F 5′-ctctgcgctcctccgcggtcatgacctgtg, R 5′-cacaggtcatgaccgcggaggagcgcagag; M101A F 5′-cgctcctcctgggtcgcgacctgtgcatatgc, R 5′-gcatatgcacaggtcgcgacccaggaggagcg; L117AF 5′-gtggcctgcggtggcgcggataacatttgctcc, R 5′-ggagcaaatgttatccgcgccaccgcaggccac; T143A F 5′-agctggcaggacacgcaggttacctgtcc, R 5′-ggacaggtaacctgcgtgtcctgccagct; Y145A F 5′-ggcaggacacacaggtgccctgtcctgctgcc, R 5′-ggcagcaggacagggcacctgtgtgtcctgcc; D186A F 5′-ccggacacactggagctgtcatgagcctttc, R 5′-gaaaggctcatgacagctccagtgtgtccgg; M188A F 5′-ggacacactggagatgtcgcgagcctttctcttgctcc, R 5′-ggagcaagagaaaggctcgcgacatctccagtgtgtcc; N230A F 5′-ggccacgagtctgacatcgctgccatttgcttctttcc, R 5′-ggaaagaagcaaatggcagcgatgtcagactcgtggcc; W332A F 5′-gtggcgacagggtccgcggatagcttcctcaa, R 5′-ttgaggaagctatccgcggaccctgtcgccac. Sequence encoding amino acids 493-689 of mouse adrenergic receptor kinase β1 was subcloned into pCS2 vector (Primer sequences: F 5′ gcaaggccggccaatgggaatcaagttactggac, R 5′ gcaaggcgcgccgaggccgttggcactgcc). Gγ2CAAX pCS2 was generated by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis (F5′ gcaaggccggccaatggccagcaacaacaccgcc R5′ gcaaggcgcgccttaaaggatggcagagaaaaac). All other constructs used have been described previously. Gαs and myristoylated GαoA, GαoB, Gαi2, and Gαi3 were expressed and purified from bacteria, and Gβ1γ2 and Gαq were purified from Sf9 cells as previously described [42-46]. Heterotrimeric G proteins were purified from porcine brain (Wampler’s Sausage Factory, TN) and Gαt was purified from bovine rod outer segments following previously described protocols [16, 47]. Gβγ was concentrated to 1 mg/mL in 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM MgSO4, and 40 mM β-octyl glucoside. GSK3 and CKI proteins were purchased from New England Biolabs.

G protein activation

To activate GαoA, GαoB, Gαi2, Gαi3, and Gαs, proteins were diluted 1:20 (v/v) with 50 mM HEPES pH 8, 1mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM MgSO4, and 10 μM GTPγS and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. Proteins were concentrated to their original volumes using Centricon-10 (Millipore). To activate Gα12, protein was diluted 1:1 (v/v) with 80 mM HEPES pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 22 mM MgSO4, 0.05% Lubrol, and 20 μM GTP©S and incubated at 30°C for 90 min. Gα13 was activated by diluting 1:1 (v/v) with 80 mM HEPES pH 8, 1mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 3 mM MgSO4, 0.05% Lubrol, and 20 μM GTPγS and incubated at 30°C for 90min. Excess GTPγS was removed using Zeba Desalt Spin Column (Pierce). To activate purified brain heterotrimer, Gαt, and Gαq, proteins were incubated with 10 mM NaF, 30 mM AlCl3, and 10 mM MgCl2 for 45min on ice.

[35S]β-Catenin degradation and phospho-β-catenin assays

Xenopus egg extract preparation and [35S]β-catenin degradation assays were performed as previously described [15]. Samples were removed at 0 and 3hr for SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. To detect β-catenin phosphorylated by GSK3 in extract, anti-β-catenin-phospho-Ser33/Ser37/Thre41 antibody (Cell Signaling) was used for immunoblotting. Tubulin detected with anti-α-tubulin (DM1α, Sigma) served as the loading control.

TOPflash assay

HEK-293 Super TOPflash (STF) cells were cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 unit/mL streptomycin, 10% FBS. Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) was used for all transfections. Cells were lysed 48 hr post-transfection with 1X Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega) and luciferase activity was measured with Steady Glo (Promega). Luciferase activities were normalized to cell number calculated with Cell Titre Glo (Promega).

Embryo studies: Axis duplication assay and β-catenin target gene expression analysis

Capped RNA for embryo injection was synthesized from linearized plasmid DNA templates by using mMessage mMachine (Ambion). Xenopus embryos were fertilized in vitro, dejellied, and injected and cultured as previously described [48]. 2-4 cell Xenopus embryos were injected with 10nl mRNAs using Narishige IM 300 microinjector according to published methods [48]. Axis duplication was scored when embryos reached stage 21 (staging of embryos performed as previously described [49]). Animal caps were cut from stage 9 embryos and cultured in 75% Marc’s modified Ringers (MMR) [0.1 M NaCl, 2 mM KCCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 5 mM Hepes (pH 7.4)] until stage 11. RT-PCR for Siamois, Xnr3, and ODC were performed by using primers and conditions previously described (www.hhmi.ucla.edu/derobertis/index.html).

Co-immunoprecipitation studies

For co-immunoprecipitation, cells were washed with cold PBS and then lysed on ice for 30 min with nondenaturing lysis buffer (NDLB): 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% (w/v) Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors (1mg/ml leupeptin, pepstatin, and chymostatin). Lysates were diluted to 1 mg/ml with NDLB and incubated with antibody beads for 3 hr with rotation at 4°C. Beads were then washed 3X with NDLB and 1X with PBS. Proteins were eluted from beads with sample buffer and processed for SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting. To prepare antibody beads, mouse anti-HA (12CA5), rat anti-HA (Roche), or rabbit anti-Gβ (1:300, Sigma) antibodies were cross-linked to Protein G or Protein A magnetic beads (New England Biolabs) following the manufacturer’s protocols. The following antibodies were used for immunoblotting: rabbit anti-Gβ (Sigma), mouse anti-HA (12CA5), mouse anti-Myc (9E10), and rabbit anti-VSVG (Bethyl Laboratories). Tubulin was detected with anti-α-tubulin (DM1α, Sigma) and served as the loading control. For co-immunoprecipitation from Xenopus egg extracts, extracts were diluted 10X with PBS, incubated with anti-Gβ beads, and beads were processed as above. Eluted samples were immunoblotted using anti-Gβ and anti-GSK3 (BD Transduction).

Membrane protein isolation and detection of LRP6

Hela cells were cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 unit/mL streptomycin, 10% FBS. Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) was used for all transfections. For membrane preparations, Hela cells were incubated in media containing 0.6mM sodium vanadate in DMEM (without serum) for 3hr. Cells were then lysed and membrane-associated proteins isolated using ProteoExtract Native Membrane Protein Extraction kit (Calbiochem). To detect endogenous LRP6, endogenous phospho-LRP6, and transfected VSVG-LRP6, the following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-LRP6 (Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-phospho-LRP6 (Ser1490) (Cell Signaling), and rabbit anti-VSVG (Bethyl Laboratories), respectively.

In vitro protein binding assay

For in vitro binding of Gβ1γ2 and GSK3, recombinant Gβ1γ2 was incubated with Maltose binding protein (MBP) or MBP-GSK3 protein in binding buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.5 mg/mL BSA) at 4°C for 45 min. Protein G magnetic beads (New England Biolabs) crosslinked to anti-MBP antibody (Sigma) were added and the reaction was incubated at 4°C for 45 min. Beads were washed 4X with binding buffer, 2X times with PBS, and samples were eluted and analyzed by immunoblotting.

In vitro kinase assay

Tau (200 nM; r-Peptide, Tau-441) or LRP6ICD (100 nM) were pre-incubated with 200 nM or 400 nM GSK3 (New England Biolabs), respectively, 200 μM ATP, 20 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, GSK3 kinase buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.2% Tween-20) and increasing concentrations of recombinant Gβ1γ2, Go, or BSA in a total reaction volume of 20 μl. Samples were incubated at room temperature and aliquots removed at 30 min (Tau) or 15 min (LRP6ICD) for analysis by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Molecular modeling

The software program MacPyMol was used to generate a model of the Gβ1γ2 dimer (Protein Databank entry 1XHM)[50].

Quantification and statistical analyses

Quantitation of β-catenin abundance and immunoblots was performed by scanning images with Adobe Photoshop CS4 (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA, USA) and intensity of the bands was quantified with NIH ImageJ with correction for background. Statistical significance was determined by t-test, with P<0.005 considered significant.

For TOPFlash assays, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the global hypothesis of equal mean intensities for all treatment conditions. The global hypothesis of all ANOVA analyses was rejected if P < 0.05. All possible pairwise contrasts were evaluated using Tukey’s HSD procedure, which corrects for multiple comparisons within each ANOVA experiment [51]. As distributional assumptions are difficult to assess due to small sample size, a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted for each experiment. All experiments had significant Kruskal-Wallis p-values, indicating rejection of the null hypothesis of equal population medians among all treatment groups. All luciferase assays were repeated at least three times in triplicate. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

For Xenopus embryo injection data, statistical significance was determined by Fisher’s exact test.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank William Bush for his help with statistical analyses.

Funding: This work was also supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant 1 R01 GM081635 (E.L.), a Scholarship from the Pew Charitable Trusts (E.L), National Cancer Institute Grant GI SPORE P50 CA95103 (E.L), a National Institute of General Medical Studies Medical-Scientist Training Grant 5 T32 GM007347 (C.S.C.), a National Institutes of Health Cancer Biology Training Grant T32 CA09592 (K.K.J.), and a Molecular Endocrinology Training Grant 5 T 32 DK007563 (C.A.T.), and American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowships 0615162B (K.K.J.), 0815094E (K.K.J.), and 0615279B (C.A.T.), National Institute of Health grants NS037112 and NS049195 (J.R.H.).

REFERENCES

- 1.MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardner S, Maudsley S, Millar RP, Pawson AJ. Nuclear stabilization of beta-catenin and inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta by gonadotropin-releasing hormone: targeting Wnt signaling in the pituitary gonadotrope. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:3028–38. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujino H, West KA, Regan JW. Phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 and stimulation of T-cell factor signaling following activation of EP2 and EP4 prostanoid receptors by prostaglandin E2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2614–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wan M, Yang C, Li J, Wu X, Yuan H, Ma H, He X, Nie S, Chang C, Cao X. Parathyroid hormone signaling through low-density lipoprotein-related protein 6. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2968–79. doi: 10.1101/gad.1702708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson G, Wu W, Shen J, Bilic J, Fenger U, Stannek P, Glinka A, Niehrs C. Casein kinase 1 gamma couples Wnt receptor activation to cytoplasmic signal transduction. Nature. 2005;438:867–72. doi: 10.1038/nature04170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeng X, Tamai K, Doble B, Li S, Huang H, Habas R, Okamura H, Woodgett J, He X. A dual-kinase mechanism for Wnt co-receptor phosphorylation and activation. Nature. 2005;438:873–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng X, Huang H, Tamai K, Zhang X, Harada Y, Yokota C, Almeida K, Wang J, Doble B, Woodgett J, Wynshaw-Boris A, Hsieh JC, He X. Initiation of Wnt signaling: control of Wnt coreceptor Lrp6 phosphorylation/activation via frizzled, dishevelled and axin functions. Development. 2008;135:367–75. doi: 10.1242/dev.013540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu G, Huang H, Garcia Abreu J, He X. Inhibition of GSK3 phosphorylation of beta-catenin via phosphorylated PPPSPXS motifs of Wnt coreceptor LRP6. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cselenyi CS, Jernigan KK, Tahinci E, Thorne CA, Lee LA, Lee E. LRP6 transduces a canonical Wnt signal independently of Axin degradation by inhibiting GSK3’s phosphorylation of beta-catenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8032–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803025105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piao S, Lee SH, Kim H, Yum S, Stamos JL, Xu Y, Lee SJ, Lee J, Oh S, Han JK, Park BJ, Weis WI, Ha NC. Direct inhibition of GSK3beta by the phosphorylated cytoplasmic domain of LRP6 in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e4046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kornbluth S, Dasso M, Newport J. Evidence for a dual role for TC4 protein in regulating nuclear structure and cell cycle progression. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:705–19. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.4.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blow JJ, Dilworth SM, Dingwall C, Mills AD, Laskey RA. Chromosome replication in cell-free systems from Xenopus eggs. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1987;317:483–94. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1987.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gard DL, Kirschner MW. A microtubule-associated protein from Xenopus eggs that specifically promotes assembly at the plus-end. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2203–15. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.5.2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma L, Cantley LC, Janmey PA, Kirschner MW. Corequirement of specific phosphoinositides and small GTP-binding protein Cdc42 in inducing actin assembly in Xenopus egg extracts. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1125–36. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salic A, Lee E, Mayer L, Kirschner MW. Control of beta-catenin stability: reconstitution of the cytoplasmic steps of the wnt pathway in Xenopus egg extracts. Mol Cell. 2000;5:523–32. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80446-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sternweis PC, Robishaw JD. Isolation of two proteins with high affinity for guanine nucleotides from membranes of bovine brain. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:13806–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu T, DeCostanzo AJ, Liu X, Wang H, Hallagan S, Moon RT, Malbon CC. G protein signaling from activated rat frizzled-1 to the beta-catenin-Lef-Tcf pathway. Science. 2001;292:1718–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1060100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katanaev VL, Ponzielli R, Semeriva M, Tomlinson A. Trimeric G protein-dependent frizzled signaling in Drosophila. Cell. 2005;120:111–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Najafi SM. Activators of G proteins inhibit GSK-3beta and stabilize beta-Catenin in Xenopus oocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;382:365–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao Y, Wang HY. Inositol pentakisphosphate mediates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26490–502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linder ME, Ewald DA, Miller RJ, Gilman AG. Purification and characterization of Go alpha and three types of Gi alpha after expression in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:8243–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hepler JR, Kozasa T, Smrcka AV, Simon MI, Rhee SG, Sternweis PC, Gilman AG. Purification from Sf9 cells and characterization of recombinant Gq alpha and G11 alpha. Activation of purified phospholipase C isozymes by G alpha subunits. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:14367–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taussig R, Iniguez-Lluhi JA, Gilman AG. Inhibition of adenylyl cyclase by Gi alpha. Science. 1993;261:218–21. doi: 10.1126/science.8327893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gard DL, Kirschner MW. Microtubule assembly in cytoplasmic extracts of Xenopus oocytes and eggs. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2191–201. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.5.2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roychowdhury S, Rasenick MM. G protein beta1gamma2 subunits promote microtubule assembly. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31576–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smrcka AV. G protein betagamma subunits: central mediators of G protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2191–214. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8006-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krumins AM, Gilman AG. Targeted knockdown of G protein subunits selectively prevents receptor-mediated modulation of effectors and reveals complex changes in non-targeted signaling proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10250–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwang JI, Choi S, Fraser ID, Chang MS, Simon MI. Silencing the expression of multiple Gbeta-subunits eliminates signaling mediated by all four families of G proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9493–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503503102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koch WJ, Hawes BE, Inglese J, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Cellular expression of the carboxyl terminus of a G protein-coupled receptor kinase attenuates G beta gamma-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6193–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamai K, Zeng X, Liu C, Zhang X, Harada Y, Chang Z, He X. A mechanism for Wnt coreceptor activation. Mol Cell. 2004;13:149–56. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00484-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamai K, Semenov M, Kato Y, Spokony R, Liu C, Katsuyama Y, Hess F, Saint-Jeannet JP, He X. LDL-receptor-related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature. 2000;407:530–5. doi: 10.1038/35035117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott JK, Huang SF, Gangadhar BP, Samoriski GM, Clapp P, Gross RA, Taussig R, Smrcka AV. Evidence that a protein-protein interaction ‘hot spot’ on heterotrimeric G protein betagamma subunits is used for recognition of a subclass of effectors. EMBO J. 2001;20:767–76. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ford CE, Skiba NP, Bae H, Daaka Y, Reuveny E, Shekter LR, Rosal R, Weng G, Yang CS, Iyengar R, Miller RJ, Jan LY, Lefkowitz RJ, Hamm HE. Molecular basis for interactions of G protein betagamma subunits with effectors. Science. 1998;280:1271–4. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5367.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bilic J, Huang YL, Davidson G, Zimmermann T, Cruciat CM, Bienz M, Niehrs C. Wnt induces LRP6 signalosomes and promotes dishevelled-dependent LRP6 phosphorylation. Science. 2007;316:1619–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1137065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yanagawa S, Lee JS, Matsuda Y, Ishimoto A. Biochemical characterization of the Drosophila axin protein. FEBS Lett. 2000;474:189–94. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01601-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sokol SY. Analysis of Dishevelled signalling pathways during Xenopus development. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1456–67. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(96)00750-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jung H, Kim HJ, Lee SK, Kim R, Kopachik W, Han JK, Jho EH. Negative feedback regulation of Wnt signaling by Gbg-mediated reduction of Dishevelled. Exp Mol Med. 2009 doi: 10.3858/emm.2009.41.10.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angers S, Thorpe CJ, Biechele TL, Goldenberg SJ, Zheng N, MacCoss MJ, Moon RT. The KLHL12-Cullin-3 ubiquitin ligase negatively regulates the Wnt-beta-catenin pathway by targeting Dishevelled for degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:348–57. doi: 10.1038/ncb1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egger-Adam D, Katanaev VL. The trimeric G protein Go inflicts a double impact on axin in the Wnt/frizzled signaling pathway. Dev Dyn. 2009 doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Speirs CK, Jernigan KK, Kim SH, Cha YI, Lin F, Sepich DS, DuBois RN, Lee E, Solnica-Krezel L. Prostaglandin Gbetagamma signaling stimulates gastrulation movements by limiting cell adhesion through Snai1a stabilization. Development. 137:1327–37. doi: 10.1242/dev.045971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gales C, Rebois RV, Hogue M, Trieu P, Breit A, Hebert TE, Bouvier M. Real-time monitoring of receptor and G-protein interactions in living cells. Nat Methods. 2005;2:177–84. doi: 10.1038/nmeth743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Linder ME, Gilman AG. Purification of recombinant Gi alpha and Go alpha proteins from Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1991;195:202–15. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)95167-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kreutz B, Yau DM, Nance MR, Tanabe S, Tesmer JJ, Kozasa T. A new approach to producing functional G alpha subunits yields the activated and deactivated structures of G alpha(12/13) proteins. Biochemistry. 2006;45:167–74. doi: 10.1021/bi051729t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ueda N, Iniguez-Lluhi JA, Lee E, Smrcka AV, Robishaw JD, Gilman AG. G protein beta gamma subunits. Simplified purification and properties of novel isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4388–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hepler JR, Kozasa T, Gilman AG. Purification of recombinant Gq alpha, G11 alpha, and G16 alpha from Sf9 cells. Methods Enzymol. 1994;237:191–212. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)37063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee E, Linder ME, Gilman AG. Expression of G-protein alpha subunits in Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1994;237:146–64. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)37059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papermaster DS, Dreyer WJ. Rhodopsin content in the outer segment membranes of bovine and frog retinal rods. Biochemistry. 1974;13:2438–44. doi: 10.1021/bi00708a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peng HB. Xenopus laevis: Practical uses in cell and molecular biology. Solutions and protocols. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;36:657–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal Table of Xenopus laevis. (Daudin) Garland Publishing Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis TL, Bonacci TM, Sprang SR, Smrcka AV. Structural and molecular characterization of a preferred protein interaction surface on G protein beta gamma subunits. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10593–604. doi: 10.1021/bi050655i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maxwell SE, Delaney DH. Designing Experiments and Analyzing Data. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.