Abstract

Research on adolescents focuses increasingly on features of the family in predicting and preventing substance use. Multivariate analyses of data from the National Survey of Parents and Youth (N = 4,173) revealed numerous significant differences on risk variables associated with family structure on adolescent drug-related perceptions and illicit substance use. Youth from dual-parent households were least likely to use drugs and were monitored more closely than single-parent youth (p < .001). A path analytic model estimated to illuminate linkages among theoretically implicated variables revealed that family income and child’s gender (p < .001), along with family structure (p < .05), affected parental monitoring, but not parental warmth. Monitoring and warmth, in turn, predicted adolescents’ social and interpersonal perceptions of drug use (p < .001), and both variables anticipated adolescents’ actual drug use one year later (p < .001). Results reconfirm the importance of parental monitoring and warmth and demonstrate the link between these variables, adolescents’ social and intrapersonal beliefs, and their use of illicit substances.

Keywords: marijuana, smoking, drugs, alcoholic beverages, family structure

Despite massive efforts to reduce substance misuse by adolescents, the problem remains significant. After decades of intense anti-drug campaigning, current studies indicate alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use remain the most commonly used illicit substances in today’s youth culture (Johnston et al., 2008; SAMHSA, 2008a). Problem behavior theory (Jessor, 1992; Jessor & Jessor, 1977) maintains adolescent delinquent behaviors including substance use emerge as a result of interacting personality, perceived environment, and behavioral systems. Each of these contextual and individual factors represents the proneness for developing problem behavior. The personality system is composed of individual characteristics, social cognitions, attitudes, perceptions, and expectations associated with problem behavior. The environment system includes perceived models of social influence such as parental monitoring and disapproval toward delinquency, as well as competing peer influences and perceived expectations. The behavior system consists of behaviors generally defined by society as either undesirable, norm-violating, and inappropriate (e.g., drug use, violent offenses, theft, vandalism, and other criminal behaviors), or socially approved (e.g., attending church, being actively involved in school). Taken together, these personality, environmental perceptions, and behavior structures illustrate how risk inhibitors interrelate with competing factors that instigate deviant outcomes to determine one’s proneness to developing problem behavior.

Converging data indicate problem behavior is consistently prominent among young adolescents compared to other age groups (Biglan et al., 2004; Crano & Burgoon, 2002). Although drug use and other deviant behaviors tend to coincide (Jessor & Jessor, 1977), adolescent initiation and use of illicit substances serve as common precursors for deviant activity and more serious drug use (Ashton, 2002; Brecht, Greenwell, & Anglin, 2007; Haggard-Grann et al., 2006). In addition to marijuana initiation, cigarette and alcohol use have been identified as among the constellation of behaviors associated with later involvement with “harder” drugs (Griffin, Botvin, Scheier, & Nichols, 2002; Rhode et al., 2003). Adolescents younger than 15 years of age who use alcohol, for example, are four times more likely than later-onset peers to experience future dependency problems (Grant & Dawson, 1997). The magnitude of this problem is disquieting. In 2006, roughly 10 million U.S. adolescents reported alcohol use, 7.2 million of whom were classified as binge drinkers, and more than 2.6 million adolescents reported cigarette use (SAMHSA, 2006). Additional reports indicate 14.6% of 8th graders, 29.9% of 10th graders, and 42.6% of 12th graders admit to lifetime marijuana use (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2008). It is estimated that 47% of all high school students have experimented with illicit drugs at some point (Johnston et al., 2009a).

These findings are alarming, as early-onset substance use has been associated with a range of negative consequences and co-occurring problems, including developmental impairment and deficits in learning ability, poorer academic achievement, affiliation with delinquent peer groups, increased risk of contracting a sexually transmitted disease, violent victimization, and more positive expectancies toward other drug use (Brook, Adams, Balka, & Johnson, 2002; Crano, Siegel, Alvaro, Lac, & Hemovich, 2008b; Kandel, 2003; Lundqvist, 2005; Lynskey, Coffey, & Degenhardt, 2003).

Children from nontraditional families, such as those who experience the negative consequences of family disruption and divorce, appear especially prone to detrimental social and behavioral outcomes, including drug use (Astone & McLanahan, 1991; Hemovich & Crano, 2009; McNulty & Bellair, 2003; Snyder, McLaughlin, & Findeis, 2006). Although the period of early adolescence often is characterized by weaker parent-child bonds (Friedlmeier & Granqvist, 2006; Marshall, Tilton-Weaver, & Bosdet, 2005; Smetana & Daddis, 2002; Youniss & Smollar, 1985), single-parent youth have been found to be more resource deprived, experience less emotional connection with parents and less supervision, and appear more susceptible to negative peer influences than youth from intact or dual-parent families (Camara & Resnik, 1988; Hoffman, 1995; McNulty & Bellair, 2003; Rankin & Wells, 1994; Snyder et al., 2006). Although some suggest that the effect of family structure on negative youth outcomes is negligible (e.g., Ford-Gilboe, 2000), considerable evidence indicates that children of single-parent households are more likely to engage in drug use than peers living in never-divorced or re-married step-parent families.

The societal shift from traditional two-parent living arrangements to less conventional ones bears consideration. Across nearly every socio-demographic echelon, steadily declining marriage rates in combination with an upsurge of single-parent, step-parent, and cohabitating households have produced exceedingly diverse living conditions for today’s youth (Bumpass & Lu, 2000; Casper & Bianchi, 2002; McLanahan, 1999). Unmarried or cohabitating adult partners comprise more than 5 million households, and the U.S. Census Bureau (2008b) estimates that 60% of these include children. Among such increasingly diverse family structures, 19 million children currently reside in single-parent homes, 88% of which are mother-only households (U.S Census Bureau, 2008a); father-only households are among the fastest-growing family types in the U.S. (Eggebeen, Snyder, & Manning, 1996; Garasky & Meyer, 1998).

Researchers have attempted to understand variations in adolescent drug use and other emotional adjustment and behavioral outcomes across increasingly diverse family settings by investigating children living in cohabitating (Manning & Lamb, 2003), same sex (Goldberg, 2010; Joslin & Minter, 2008; Patterson, 2009; Rosenfeld, 2007), nonbiological (Rueter et al., 2009; Sun, 2003), mother-only vs. father-only (Eitle, 2006; Hoffman & Johnson, 1999; Hemovich & Crano, 2009) and remarried or step-parent families (Flewelling & Bauman, 1990; Hoffman, 2002; Wallerstein & Lewis, 2007). Though comprehensive, many such substance use studies have primarily focused on differences in trajectories of drug use outcomes as opposed to the interplay of risk and protective factors associated with variations in use. Myriad intermediate processes have been found to be strongly interrelated with the progression of early-onset substance use problems among youth, including parental monitoring and warmth, peer affiliation, academic motivation and involvement in after school clubs, delinquency, sensation-seeking, refusal strength, and normative perceptions of drug use, yet the interplay of these intrapersonal and social factors is rarely addressed in the family structure literature (Amato & Keith, 1991; Bahr, Hoffmann, & Yang, 2005; Brook, Brook, & Richter, 2001; Farrell & White, 1998; Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Kopstein et al., 2001; Lac & Crano, 2009; Siegel, Alvaro, Patel, & Crano, 2009; Stormshak, Comeau, & Shepard, 2004, Svensson, 2003; Windle, 2000; Wills, Resko, Ainette, & Mendoza, 2004; Yang et al., 2006). Although some evidence suggests these variables influence boys and girls differently (Ellickson et al., 2001; Sutherland & Shepard, 2001; Zuckerman, 2007), few studies have yet to explore how these factors combine to either promote or prevent illicit substance use by adolescents living in nontraditional households.

The present study was developed to expand current knowledge by combining variations in social and intrapersonal factors that may directly affect drug use in children of mother-only, father-only, and dual-parent families. In accord with prior studies (e.g., Hemovich & Crano, 2009), we anticipate that youth in father-only households will engage in higher levels of substance use than those from mother-only households, and both groups will report more substance usage than adolescents from dual-parent households (Barrett & Turner, 2006; Eitle, 2006; Ellickson, Tucker, Klein, & McGuigan, 2001; Fisher et al., 2003). These relationships are relatively well established, but the factors that influence them have yet to be linked unambiguously.

Additional research suggests single-parent families often are disadvantaged economically relative to dual-parent families (McNulty & Bellair, 2003; Rankin & Wells, 1994; Snyder, McLaughlin, & Findeis, 2006). We expect mother-only households will report greater economic disadvantage relative to father-only households, and both single-parent family types will display lower family income than dual-parent families, many of which contain dual wage earners. We predict that the economic stress of single parenthood for single mothers and fathers could influence the intensity of parental monitoring; that is, they may be less able to monitor and supervise their children. Relative to dual-parent families, single-parent attenuated monitoring might help explain the higher rates of problematic behavior consistently found among mother-only and father-only youth. In a further attempt to expand the research base, the current study also is designed to identify different levels of parental monitoring and parent warmth among different family structures.

Lac and Crano’s (2009) recent meta-analysis revealed a strong and consistent cross-study association of parental monitoring with lower rates of illicit substance use, but similar investigations on the role of parental warmth are markedly absent (Alvarez, Martin, Vergeles, & Martin, 2003). Given the emergence of increasingly diverse households and the established role of parental monitoring on mitigating adolescent problem behaviors, it is surprising that relatively little empirical study has been devoted to identifying how family environment factors such as monitoring and warmth might vary across mother-only, father-only, and dual-parent family structures, and the effects of these variables on adolescent substance use behavior.

In adolescence, peers also assume an increasingly important role in guiding behaviors (Andrews, Tildesley, Hops, & Li, 2002; Bahr et al., 2005; Borsari, & Carey, 2006; Collins & Laursen, 2004; Maxwell, 2002; Ramirez et al., 2004). The influence vacuum created in youth who are not closely monitored by parents can be expected to be filled by peers. If less parental monitoring is found in single-parent homes, then less closely monitored youth from these families may be more influenced by peers than youth from dual-parent households. This, in turn, could result in more susceptibility to deviant peers, more positive friend and peer marijuana norms, higher approval of others’ marijuana use, lower levels of drug refusal strength, and greater self-reported delinquency. In short, we expect these more positive substance-relevant attitudes and normative beliefs may help explain why higher levels of illicit substance use are routinely found among single-parent versus dual-parent youth.

Method

Data were drawn from the restricted version of the National Survey of Parents and Youth (NSPY). A nationally representative survey, the NSPY evaluated adolescents’ drug use, related attitudes, beliefs, and parenting factors. Participants were selected using a complex multi-stage sampling design, incorporating clustering and stratification. At least two weeks prior to the interviews, letters were mailed to potential households indicating that an interviewer would contact and screen them to determine their eligibility to participate in the interview. Eligibility was determined by the sampling methodology. Of the successfully screened youth aged 12–18 deemed eligible, 91.0% completed the interview. Each youth received $20 for participating. At the sampled household, a trained interviewer obtained assent from the child as well as parental consent prior to proceeding with the interview. Non-sensitive data (e.g., demographic information) were collected via computer-assisted personal interview. Sensitive data (e.g., drug consumption perceptions and behaviors) were collected via audio-computer-assisted self-interviewing, allowing respondents to self-administer the questionnaire using headphones and a touch-sensitive computer screen.

For the current study, data obtained from two rounds of interviews conducted during the November 1999 to June 2001 project period were used. Each interview was separated by approximately 12 months. Sampling weights available in the dataset were applied to ensure that results were nationally representative of U.S. adolescents. The cross-sectional general sampling weight was applied to the group-based tests of mean differences, and data used in the path model to be described were weighted with the longitudinal general sampling weight to maintain national representativeness and to correct for participant attrition occurring across the two administrations (Kaplan & Ferguson, 1999).

Respondents

The sample consisted of 4,173 respondents ranging in age from 12 to 18 years (M = 14.78, SD = 1.87). Gender was approximately evenly distributed (boys comprised 51.3% of the sample). Racial composition of the sample was as follows: 67.7% White, 14.6% Black, 14.2% Hispanic, and 3.5% Asian. The majority of youth resided in dual-parent households (67.8%, n = 2831), followed by mother-only (27.7%, n = 1155), and father-only (4.5%, n = 187) households.

Measures

Demographic characteristics: age, gender, and family structure were assessed in the survey Also, parents/caregivers (hereafter, parents) reported total household family income. For the measures listed below, the scale range, Cronbach’s alpha, means, and standard deviations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Information on Measured Variables

| Measure | Scale Range | Cronbach’s alpha | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental | ||||

| Family income | 1 (under $10,000) to 8 ($100,000 or above) | -- | 5.06 | 1.91 |

| Parental monitoring | 1 (never or almost never) to 5 (always or almost always) | 0.79 | 3.78 | 1.14 |

| Parental warmth | 1 (never or almost never true) to 5 (always or almost always true) | 0.82 | 3.64 | 1.11 |

| Social | ||||

| Involvement in clubs/activities | 0 (no activities) to 5 (5 activities) | -- | 2.22 | 1.29 |

| Peer marijuana norms | 1 (none) to 5 (all) | 0.83 | 2.59 | 0.98 |

| Friend marijuana norms | 1 (none) to 5 (all) | -- | 2.06 | 1.09 |

| Adult supervsion | 1 (never) to 5 (always or almost always) | -- | 2.94 | 1.22 |

| Self delinquency | 1 (not at all) to 5 (5 or more times) | 0.52 | 1.28 | 0.52 |

| Peer delinquency | 0 (never) to 6 (more than 7 times) | 0.77 | 1.82 | 1.15 |

| Intrapersonal | ||||

| Refusal strength | 1 (not at all sure I can say no) to 5 (completely sure I can say no) | 0.91 | 4.57 | 0.83 |

| Sensation seeking | 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) | 0.80 | 2.75 | 0.93 |

| Approval of others’ mar use | 1 (strongly disapprove) to 5 (strongly approve) | 0.82 | 1.84 | 0.92 |

| Substance Use | ||||

| Cigarette use | 1 (never) to 5 (I have smoked in the last 30 days) | -- | 1.84 | 1.34 |

| Alcohol use | 1 (no) to 4 (during the last 30 days) | -- | 2.00 | 1.19 |

| Marijuana use | 1 (no) to 4 (during the last 30 days) | -- | 1.45 | 0.92 |

Note . Measures not reporting Cronbach’s alpha are single-item.

Parental monitoring was operationalized as the mean of the following items: “In general, how often does at least one of your {parents/caregivers}” (a) “Know what you are doing when you are away from home?” (b) “Have a pretty good feeling of your plans for the upcoming day?”

Parental warmth was operationalized as the mean of two items: “Think about the last 30 days. How true are the following statements for you:” (a) “I really enjoyed being with my {parents/caregivers}.” (b) “There was a feeling of togetherness in our family.”

Social Variables

Involvement in clubs/activities consisted of 5 items: “In the last 12 months, have you ever participated in the following types of organized activities or groups:” (a) “Music, dance, theater or other performing arts, in or outside of school?” (b) “Athletic teams or organized sports, in or outside of school?” (c) “Boys or girls clubs, such as Boy Scouts or Girl Scouts?” (d) “Youth groups sponsored by a church, synagogue, mosque, or other religious institution?” (e) “Another club or activity, in or outside of school, or volunteer work?” Activities for each respondent were summed to yield a score that could range from 0 to 5.

Peer marijuana norms was operationalized as the mean of two items: (a) “How many {kids in your grade at school/kids your age} have used marijuana, even once or twice in the last 12 months?” (b) “How many {kids in your grade at school/kids your age} have used marijuana nearly every month in the last 12 months?” Item stem variants depended on whether the youth had attended school at any time in the prior year.

Friend marijuana norms were determined by: “How many of your friends do you think have used marijuana (even once or twice/nearly every month) in the last 12 months?” Respondents received one of the variants.

Adult supervision was determined by: “How often do you spend your free time in the afternoons hanging out with friends without adults around?” Response options were scored from 1 (never) to 5 (always or almost always).

Self delinquency was operationalized as the mean of three items: “During the last 12 months, how often have you:” (a) “Gotten into a serious fight in school or at work?” (b) “Taken something not belonging to you worth under $50?” (c) “Damaged school property on purpose?”

Peer delinquency was operationalized as the mean of three items: “In the last 7 days, how many times did you get together with friends who:” (a) “Get into trouble a lot?” (b) “Fight a lot?” (c) “Take things that don’t belong to them?”

Intrapersonal Variables

Refusal strength was operationalized as the mean of five items. “How sure are you that you can say no to marijuana, if you really wanted to, if:” (a) “You are at a party where people are using it.” (b) “A very close friend suggests you use it.” (c) “You are home alone and feeling sad or bored.” (d) “You are on school property and someone offers it.” (e) “You are hanging out a friend’s house whose parents aren’t home.”

Sensation seeking was operationalized as the mean of: (a) “I would like to explore strange places.” (b) “I like to do frightening things.” (c) “I like new and exciting experiences, even if I have to break the rules.” (d) “I prefer friends who are exciting and unpredictable.”

Approval of others’ marijuana use was operationalized as the mean of two items: “Do you disapprove or approve of people doing each of the following:” (a) “Trying marijuana once or twice.” (b) “Using marijuana nearly every month for 12 months.”

Substance Use

Cigarette use was measured by the item, “Have you ever smoked part or all of a cigarette?”

Alcohol use was operationalized by asking respondents, “Have you ever, even once, had a drink of any alcoholic beverage, that is, more than a few sips?” Those responding yes were asked, “How long has it been since you last drank an alcoholic beverage, more than a few sips?” Responses from both items were combined to construct a scale of alcohol use.

Marijuana use. “Have you ever, even once, used marijuana?” Those responding yes were asked, “How long has it been since you last used marijuana?” Responses were combined to construct a scale of marijuana use.

Results

Analytic Plan

Group-based mean differences on dependent measures associated with parental, social, intrapersonal, and substance use were evaluated with a 2 (youth’s gender: boy or girl) × 3 (family structure: father-only, mother-only, or dual-parent) MANOVA, followed by ANCOVAs to assess specific effects. Family income was specified as the covariate in these analyses. Results were estimated using data from Time 1. Then, to clarify the multivariate linkages between these factors, a path model was hypothesized. Adolescents’ gender, family structure, and family income were used to predict perceptions of parental monitoring and parental warmth, which then were used to predict social and intrapersonal perceptions toward substance use. These social and intrapersonal perceptions were used to predict substance use one year later. For the purpose of estimating the longitudinal model, data from respondents who participated in both Time 1 and Time 2 measurements were used.

Mean Differences

Group-based multivariate differences

To examine overall differences on all critical variables, a 2 (youth’s gender: boy or girl) × 3 (family structure: single-father, single-mother, or dual-parent) multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was performed. Family income was statistically controlled in the analyses to rule it out as a rival explanation of family structure effects. This covariate was statistically significant, F(14, 4153) = 16.21, p < .001, as were the two multivariate main effects: child’s gender, F(14, 4153) = 7.08, p < .001, and family structure, F(28, 8308) = 2.87 p < .001. The multivariate interaction involving the two independent variables was not significant. As the multivariate main effects were statistically significant, 2 × 3 (child’s gender × family structure) ANCOVAs controlling for family income were undertaken on each outcome measure.

Gender differences

Level of family income, the covariate, did not statistically differ between boys and girls. After controlling for family income, systematic mean differences associated with child’s gender were found on 7 of the 14 dependent measures (Table 2). Boys expressed higher self delinquency, peer delinquency, and sensation seeking (p < .05). Girls averaged significantly higher scores on parental monitoring, peer marijuana norms, adult supervision, and refusal strength (p < .05).

Table 2.

Mean Differences as a Function of Child’s Gender

| Measure | Boys

|

Girls

|

F-test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | ||

| Parental | |||||

| Family income | 5.01 | (1.92) | 5.10 | (1.91) | 0.73 |

| Parental monitoring | 3.63 | (1.12) | 3.93 | (1.14) | 10.22** |

| Parental warmth | 3.64 | (1.09) | 3.64 | (1.16) | 0.03 |

| Social | |||||

| Involvement in clubs/activities | 2.11 | (1.27) | 2.33 | (1.33) | 1.96 |

| Peer marijuana norms | 2.50 | (0.95) | 2.68 | (1.00) | 12.23*** |

| Friend marijuana norms | 2.09 | (1.09) | 2.02 | (1.10) | 0.06 |

| Adult supervsion | 2.84 | (1.20) | 3.06 | (1.22) | 6.45** |

| Self delinquency | 1.34 | (0.58) | 1.21 | (0.42) | 13.99*** |

| Peer delinquency | 1.92 | (1.22) | 1.70 | (1.06) | 8.04** |

| Intrapersonal | |||||

| Refusal strength | 4.51 | (0.89) | 4.63 | (0.76) | 14.54*** |

| Sensation seeking | 2.85 | (0.96) | 2.62 | (0.88) | 15.36*** |

| Approval of others’ mar use | 1.86 | (0.94) | 1.82 | (0.88) | 3.78 |

| Substance Use | |||||

| Cigarette use | 1.83 | (1.34) | 1.81 | (1.34) | 0.31 |

| Alcohol use | 1.99 | (1.20) | 1.99 | (1.18) | 0.61 |

| Marijuana use | 1.48 | (0.96) | 1.38 | (0.86) | 1.05 |

Note . Statistical tests of child’s gender main effects are from the 2 (gender) × 3 (family structure) ANCOVA models, controlling for family income. Family income is from 2 (gender) × 3 (family structure) ANOVA model.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Family structure differences

Family income significantly differed across the three types of family structures: mean family income of dual-parent families was significantly greater than that of single-father households, whose income exceeded that of single-mother households. After controlling for family income, statistically significant main effects were found as a function of family structure on 12 of the 14 dependent measures (Table 3). To explore the main effects of family structure, follow-up tests of simple effects were conducted to examine differences between father-only, mother-only, and dual-parent households. This follow-up analysis of the significant main effect revealed a number of noteworthy directional differences: In comparison to mother-only households, youth from father-only homes had significantly higher peer marijuana norms, approval of others’ marijuana use, cigarette use, alcohol use, and higher levels of marijuana use (p < .05; see Table 3 for a complete set of means comparisons).

Table 3.

Mean Differences as a Function of Family Structure

| Measure | Father-Only | Mother-Only | Dual-Parent | Omnibus F -test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | ||

| Parental | |||||||

| Family Income | 4.75a | (1.61) | 3.66b | (1.79) | 5.68c | (1.64) | 647.30*** |

| Parental monitoring | 3.57a | (1.19) | 3.62a | (1.20) | 3.85b | (1.10) | 11.69*** |

| Parental warmth | 3.67a | (1.18) | 3.62a | (1.14) | 3.65a | (1.11) | 0.89 |

| Social | |||||||

| Involvement in clubs/activities | 1.98a | (1.18) | 1.98a | (1.31) | 2.33b | (1.28) | 7.59** |

| Peer marijuana norms | 2.81a | (1.02) | 2.63b | (1.02) | 2.56c | (0.96) | 8.72*** |

| Friend marijuana norms | 2.34a | (1.14) | 2.21a | (1.18) | 1.97b | (1.05) | 19.72*** |

| Adult supervision | 2.76a | (1.29) | 2.90ab | (1.28) | 2.98b | (1.18) | 7.77*** |

| Self delinquency | 1.32ab | (0.56) | 1.32a | (0.56) | 1.25b | (0.49) | 7.77*** |

| Peer delinquency | 1.84ab | (1.23) | 1.91a | (1.28) | 1.77b | (1.09) | 3.49* |

| Intrapersonal | |||||||

| Refusal strength | 4.39a | (0.91) | 4.43a | (0.96) | 4.64b | (0.75) | 15.62*** |

| Sensation seeking | 2.78a | (0.97) | 2.67a | (0.97) | 2.76a | (0.91) | 0.48 |

| Approval of others’ mar use | 2.14a | (1.06) | 1.98b | (0.95) | 1.76c | (0.87) | 44.30*** |

| Substance use | |||||||

| Cigarette use | 2.29a | (1.56) | 1.95b | (1.42) | 1.74c | (1.28) | 19.23*** |

| Alcohol use | 2.35a | (1.20) | 2.01b | (1.18) | 1.95b | (1.19) | 12.54*** |

| Marijuana use | 1.82a | (1.16) | 1.54b | (1.00) | 1.37c | (0.85) | 32.32*** |

Note . Statistical tests of family structure main effects are from the 2 (child’s gender) × 3 (family structure) ANCOVA models, controlling for family income. Family income is from 2 (gender) × 3 (family structure) ANOVA model. Within the same row, means not sharing a subscript are statistically significant in tests of simple effects.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Between father-only and dual-parent homes, significant differences emerged on parental monitoring, involvement in clubs/activities, peer marijuana norms, friend marijuana norms, adult supervision, refusal strength, approval of other’s marijuana use, cigarette use, alcohol use, and marijuana use (p < .05). Mother-only and dual-parent households were statistically different on parental monitoring, involvement in clubs/activities, peer marijuana norms, friend marijuana norms, self delinquency, peer delinquency, refusal strength, approval of other’s marijuana use, cigarette use, and personal marijuana use (p < .05). Overall, riskier patterns associated with substance use were most pronounced in father-only households and least evident in dual-parent households (Table 3).

Predictive Model

To this point, the analyses have involved cross-sectional data. To provide an explanatory multivariate model linking predictive factors with later substance use, we estimated a longitudinal path model to determine whether family income, child’s gender, and family structure affected parental monitoring and warmth, which in turn were hypothesized to affect adolescents’ social and intrapersonal beliefs and attitudes. As we suspected that household income was significantly lower in single-parent households, family income was allowed to correlate with single-father and single-mother households. In this model, to parsimoniously capture each construct, mean composites representing parental monitoring (α = .74), parental warmth, (α = .82) social (α = .69), as well as intrapersonal beliefs (α = .55) were constructed from their respective indicators. Furthermore, an index of Time 2 substance use (α = .76) was developed, which combined past month tobacco, past year alcohol, and past year marijuana use, measured in the second measurement round, approximately one year after the predictor variables were assessed.

Measures representing each factor were standardized, as some were based on different measurement scales, before their respective composites were formed. Family structure, consisting of 3 groups (mother-only, father-only, and dual-parent), was dummy coded with dual-parent households serving as the reference group. A total of 3,034 participants (72.71% of the sample) completed measures from both rounds. As the path model was weighted to reflect participant attrition due to subjects’ aging out of the study (at 19 years of age) or non-response, the reduction in sample size does not affect generalizability.

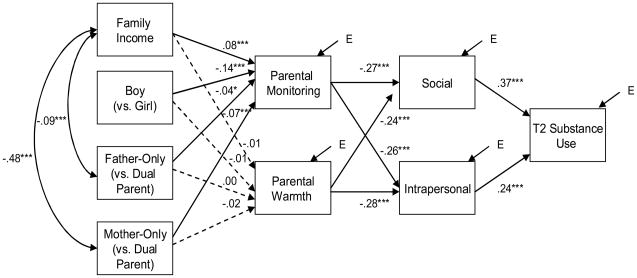

The hypothesized path model (Figure 1) was specified with EQS 6.1 (Bentler, 2001). The model approximated the underlying data to produce an acceptable fit: CFI = .97, NNFI = .95, RMSEA = .033 (90% CI: .025 to .040), S-B X2(18) = 76.65, p < .001. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) typically range from 0.00 to 1.00, with higher values representing better fit (Ullman & Bentler, 2003). The RMSEA, a residual-based index, indicates poor fit if levels exceed .10 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). A non-significant S-B X2 test reflecting good fit is desired (Satorra & Bentler, 1994), but the test is sensitive to model rejection when the sample size, like that of this study, is large (Bollen, 1989).

Figure 1.

Path analytic model of Time 1 family income, child’s gender, and family structure and Time 2 substance use

Note. Solid paths are statistically significant. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. For diagrammatic clarity, not displayed are the correlation of error terms between parental monitoring and parental warmth (r = .43, p < .001) and between social and intrapersonal perceptions (r = .48, p < .001).

Close inspection of the model revealed that the majority of the hypothesized pathways were statistically significant. Lower family income (β = .08, p < .001), male gender (β = − .14, p < .001), father-only households (β = − .04, p < .05), and mother-only households (β = − .07, p < .001) were related to lower perceptions of parental monitoring; however, none of these variables predicted perceptions of parental warmth. Both parental monitoring and parental warmth (β = −.27, − .24, respectively, p < .001) were inversely related to pro-substance social perceptions. Similarly, parental monitoring and parental warmth (β = − .26 and − .28, respectively, p < .001) negatively predicted pro-substance intrapersonal perceptions. Both social and intrapersonal perceptions (β = .37 and .24, respectively, p < .001) uniquely predicted adolescents’ substance use at Time 2. A noteworthy finding is that the correlation between higher family income was negatively associated with mother-only (r = −.48, p < .001) and father-only households (r = −.09, p < .001), suggesting that single parent households possess fewer financial resources than dual-parent households. Furthermore, tests of indirect effects through all the mediating factors (parental monitoring, parental warmth, social perceptions, and intrapersonal perceptions) of this model were performed. Statistically significant indirect effects were found starting from each income (p < .05), gender (p < .001), and mother-only households (p < .01) to T2 drug use, indicating that the mediating factors were involved in carrying these effects. The indirect effect of father-only to T2 drug use was not statistically significant, likely due to the lack of power associated with the relatively small proportion of single-father households in the data.

A second, alternative model also was estimated. This model was identical to the first, except that it controlled for initial usage status. That is, all estimated paths remained the same, except social and intrapersonal factors were now also allowed to predict a newly incorporated T1 substance use factor, which in turned predicted T2 substance use. All previously significant paths as well as the newly modeled paths were found to be statistically significant. Fit indices for this model were found to be high: CFI = .98, NNFI = .96, RMSEA = .031 (90% CI: .024 to .037), S-B X2(24) = 93.38, p < .001. As analysis of this model produced results parallel to those presented, it is not discussed further.

Discussion

The increase in nontraditional households across the United States has prompted a flurry of research activity designed to investigate the role of family structure on behavioral outcomes among today’s adolescents. Over the past 30 years, problem behavior theory (Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Jessor, 1992) has guided numerous scientific efforts attempting to better explain the covariations of individual and environmental influences on the etiology and developmental trajectory of youth problem behavior, and substance abuse differences among youth from single-and dual-parent households continues to receive considerable attention (Astone & McLanahan, 1991; McNulty & Bellair, 2003; Snyder et al., 2006). Despite these endeavors, the effects of differences in adolescents’ social and interpersonal perceptions attributable to variations in family structure have received less attention. However unintentional, the omission of these intermediate factors may seriously limit our understanding of the role of family structure variations in adolescent substance misuse.

Multivariate analysis indicated that youth from single-parent families engaged in significantly higher levels of substance use than those from dual-parent households. More specifically, youth from father-only households engaged in higher levels of cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use than those from mother-only and dual-parent households. Adolescents from mother-only households engaged in significantly more cigarette and marijuana use than youth from dual-parent households; however, their alcohol use did not differ from that of youth from dual-parent families. These results both confirmed our expectations and replicated earlier findings (Barrett & Turner, 2006; Eitle, 2006; Hemovich & Crano, 2009).

Also consistent with expectations, analyses confirmed the financial stress hypothesis. Owing to the press of financial exigencies (e.g., the need to work long hours or to hold multiple jobs), it seemed plausible to assume that single-parents, on average, would be less able to monitor their children consistently and intensively. Results appeared to confirm these expectations. Mean family income of dual-parent families significantly exceeded that of single-parent households. Analyses also revealed statistically significant differences in monitoring as a function of household structure. Parental monitoring in dual-parent families was significantly greater than that reported by respondents in single-parent families (Table 3). However, parental warmth did not differ systematically among family structures, nor was it related to child’s gender or family income. In combination, this examination of family income and parental monitoring suggests parent-child emotional bonds are relatively constant and are not necessarily influenced by family structure variations. However, although parental warmth in single-parent families is similar to that of dual- parent families, the level of monitoring in single-parent families was notably less. These findings suggest that future community based prevention and intervention efforts might provide single-parent households additional resources to facilitate monitoring or, at a minimum, to offer mass media campaigns that emphasize the importance of parental monitoring in preventing children’s substance use.

The established link between attenuated parental monitoring and adolescent substance use was hypothesized to operate through adolescents’ social and intrapersonal beliefs and attitudes. We speculated that if parents’ availability were constrained (as the income results suggest), then adolescents might gravitate to peers for information and alternate behavioral models. This migration from parents to peers is a common feature of adolescent development (Bush et al., 1994; Glynn, 1981; Kandel, 1996; Krosnick & Judd, 1982). However, with attenuated parental monitoring, this movement-to-peers may overshoot the mark and adolescents may become overly dependent on peers as sources of information regarding appropriate or normative behavior. This process may lead to a greater openness to illicit substances, higher levels of self-reported and peer delinquency, overestimates of friends’ and peers’ drug use norms, higher approval of others’ drug use, lower refusal strength, and ultimately, higher levels of substance use. As summarized in Table 3, our findings present strong evidence that differences between single- and dual-parent family structures indeed are associated with a complex of beliefs and attitudes that inclines adolescents to illicit substance use. Youth from single-parent families reported significantly less involvement in clubs and organized activities than dual-parent youth, less adult supervision, significantly more positive pro-drug friend and peer norm perceptions, and greater self- and peer delinquency.

Analysis of the interpersonal difference factors revealed that single-parent respondents’ approval of others’ marijuana use was significantly greater than that of youth from dual-parent households, and their refusal strength was significantly less. Well-defined factors such as refusal strength, normative perceptions of peer use, sensation-seeking, delinquency, and acceptance of drug-using peers have all been shown in past research to contribute to substance use behavior (Bahr et al., 2005; Farrell & White, 1998; Hawkins et al., 1992; Kopstein et al., 2001; Lac & Crano, 2009; Siegel et al., 2009; Svensson, 2003; Wills et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2006). However, few studies have linked these differences to family structure variations, and none have demonstrated how economic and family structure differences relate to parental monitoring and warmth. To date, research also has not established how these factors may create differences in adolescents’ social and intrapersonal beliefs and attitudes, which in turn may affect use of harmful substances. The present research offers a plausible picture of this process. It is important to note that there were no differences in sensation seeking as a function of single- vs. dual-parent family structures. This is reasonable, as variations in family structure would not be expected to affect sensation seeking if it is a biologically based personality trait, as Donohew (2006) and his collaborators have suggested (Donohew, Palmgreen, Lorch, Zimmerman, & Harrington, 2002).

The manner in which these various factors fit together in a causal chain to predict substance use is detailed in Figure 1. Family income and household status were hypothesized to predict parental monitoring, and statistically significant paths linked these exogenous variables with monitoring. Sex of child also predicted parental monitoring; girls were monitored more closely than boys. This result was not formally hypothesized, but it is included in the theoretical model as it is reasonably well established from prior research (Giordano & Cernkovich, 1997; Li, Feigelman, & Stanton, 2000; Svensson, 2003; Webb et al., 2002).

A central goal of the current study was to understand why youth from single-parent households consistently exhibit more delinquency and problematic substance use behavior than peers from dual-parent households. It seemed reasonable to assume that economic stress associated with single-parent status would affect monitoring, which has been associated with adolescent substance use, and significant differences in family income indeed were found as a function of family status. Family status, income, and child’s gender all anticipated variations in parental monitoring, but they did not affect parental warmth. Monitoring and warmth, in turn, predicted variations in adolescents’ attitudes toward substance users, their friendship choices, norm perceptions, and refusal strength. These social and interpersonal factors significantly predicted substance use one year after the predictive variables were collected. This use of longitudinal data offers significant advantages when using structural equation models to postulate causal relations (Crano & Brewer, 2002; Crano & Mendoza, 1987). The fit indices of the path model that describes the anticipated relationships were clearly acceptable.

Some potentially limiting features of the research should be considered in weighing these results. Self-report measures of substance use, used throughout this study, have raised validity concerns in the past (Morral et al., 2003), but research suggests that underreporting problems are relatively minor (Cornelius et al., 2004; Fendrich et al., 2004). Further, the analyses do not specify the reasons underlying single-parent family status, which could affect outcomes appreciably; however, it was not possible with available data to determine if single-parenthood was attributable to never having been married, divorce, abandonment, death of a spouse, or other causes. Even so, use of a large and nationally representative sample of adolescents from diverse family structures is an important advance over many earlier studies, and suggests that no matter the cause, single-parent family status may create substance use vulnerabilities in adolescents. This is not to suggest that traditional dual-parent households will adequately shield adolescents from illicit substance use, but rather reinforces the importance of parental monitoring on children’s behavior. Structural and social features that reduce monitoring must be recognized and their effects offset.

To our knowledge, this study is the first simultaneously to examine the role of family status, gender, and family income on adolescents’ drug use norm perceptions, refusal strength, and drug use approval. These variables often prove decisive in predicting drug use (Crano et al., 2008a, b; Farrell & White, 1998; Kopstein et al., 2001; Lac & Crano, 2009; Svensson, 2003; Wills et al., 2004), but they are largely ignored in the family structure literature. While the bulk of previous family structure research capitalized on mean outcome contrasts between children from varying household structures, the path analytic approach affords the opportunity to investigate previously unexplored intermediate pathways linking family structure with drug use. The path analysis revealed links between family structure and various social and intrapersonal factors that significantly foreshadow adolescent drug use. The analysis indicated that less parental monitoring and lower warmth expressed in the family gave rise to youth who were more socially and intrapersonally inclined to substance use. These more favorable drug use attitudes and perceptions, in turn, resulted in higher usage.

The results have implications for prevention and underscore important dissimilarities across of a host of social and intrapersonal variables among youth living in diverse family settings. While past studies that have employed univariate tests are informative, it is necessary at this point to develop a multivariate vision of adolescent drug use determinants and the interconnected processes that anticipate use if we are to advance our understanding of the effects of family structure on adolescent illicit substance use. We believe the approach detailed here provides a means of attaining this more complete picture of the complex and circuitous pathways that may lead adolescents from diverse families to the use of illicit substances.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA030490-01). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of NIDA or the Department of Health and Human Services. We are grateful to Dr. Norbert Semmer for his careful commentary on an earlier version of this work.

References

- Alvarez J, Martin AF, Vergeles MR, Martin AH. Substance use in adolescence: Importance of parental warmth and supervision. Psicothema. 2003;15:161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Aquilino WS, Supple AJ. Long-term effects of parenting practices during adolescence on well-being outcomes in young adulthood. Journal of Family Issues. 2001;22:289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Tildesley E, Hops H, Li F. The influences of peers on young adult substance use. Health Psychology. 2002;21:349–357. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton H. Cannabis or health? Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2002;15:247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Astone NM, McLanahan SS. Family structure, parental practices, and high school completion. American Sociological Review. 1991;56:309–320. [Google Scholar]

- Bahr SJ, Hoffmann JP, Yang X. Parental and peer influences on the risk of adolescent drug use. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2005;26:529–551. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AE, Turner RJ. Family structure and substance use problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Examining explanations for the relationship. Addiction. 2006;101:109–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. EQS 6 structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Brennan PA, Foster SL, Holder HD. Helping adolescents at risk: Prevention of multiple problem behaviors. New York: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. How the quality of peer relationships influences college alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25:361–370. doi: 10.1080/09595230600741339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecht M, Greenwell L, Anglin M. Substance use pathways to methamphetamine use among treated users. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:24–38. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Adams RE, Balka EB, Johnson E. Early adolescent marijuana use: Risks for the transition to young adulthood. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:79–81. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Richter L. Risk factors for adolescent marijuana use across cultures and across time. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2001;162:357–374. doi: 10.1080/00221320109597489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass L, Lu H. Trends in cohabitation and implications for children’s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies. 2000;54:29–41. doi: 10.1080/713779060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush PJ, Weinfurt KP, Iannotti RJ. Families versus peers: Developmental influences on drug use from grade 4–5 to grade 7–8. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1994;15:437–456. [Google Scholar]

- Camara RA, Resnik G. Interpersonal conflict and cooperation: Factors moderating children’s post-divorce adjustment. In: Hetherington EM, Arasteh JD, editors. Impact of divorce, single-parenting, and stepparents on children. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Casper LM, Bianchi SM. Continuity and change in the American family. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Laursen B. Parent-adolescent relationships and influences. In: Lerner R, Steinberg LL, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius M, Leech S, Goldschmidt L. Characteristics of persistent smoking among pregnant teenagers followed to young adulthood. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2004;6:159–169. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crano WD, Burgoon M. Mass media and drug prevention: Classic and contemporary theories and research. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Crano WD, Brewer MB. Principles and methods of social research. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Crano WD, Mendoza JL. Maternal factors that influence children’s positive behavior: Demonstration of a structural equation analysis of selected data from the Berkeley Growth Study. Child Development. 1987;58:38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Crano WD, Gilbert C, Alvaro EM, Siegel J. Enhancing prediction of inhalant abuse risk in samples of early adolescents: A secondary analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2008a;33:895–905. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crano WD, Siegel J, Alvaro EM, Lac A, Hemovich V. The at-risk adolescent marijuana nonuser: Expanding the standard distinction. Prevention Science. 2008b;9:129–137. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0090-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crano WD, Ting SA, Hemovich V. Inhalants. In: Cohen L, Collins F, Young A, McChargue D, Leffingwell’s T, editors. The Pharmacology and Treatment of Substance Abuse: An Evidence Based Approach. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Demo DH, Acock AC. Family structure, family process, and adolescent well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1996;6:457–488. [Google Scholar]

- Donohew L. Media, sensation seeking, and prevention. In: Vollrath ME, editor. Handbook of personality and health. New York, NY: Wiley; 2006. pp. 299–313. [Google Scholar]

- Donohew L, Palmgreen P, Lorch E, Zimmerman R, Harrington N. Attention, persuasive communication, and prevention. In: Crano WD, Burgoon M, editors. Mass media and drug prevention: Classic and contemporary theories and research. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 119–143. [Google Scholar]

- Eggebeen DJ, Snyder AR, Manning WD. Children in single-father families in demographic perspective. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:441–465. doi: 10.1177/019251396017004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitle D. Parental gender, single-parent families, and delinquency: Exploring the moderating influence of race/ethnicity. Social Science Research. 2006;35:727–748. [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ, McGuigan KA. Prospective risk factors for alcohol misuse in late adolescence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:773–782. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, White KS. Peer influences and drug use among urban adolescents: Family structure and parent adolescent relationship as protective factors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:248–258. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendrich M, Mackesy-Amiti M, Johnson T, Hubbell A, Wislar J. Tobacco-reporting validity in an epidemiological drug-use survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;30:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Leve LD, O’Leary CC, Leve C. Parental monitoring of children’s behavior: Variation across stepmother, stepfather, and two-parent biological families. Family Relations. 2003;52:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Flewelling RL, Bauman KE. Family structure as a predictor of initial substance use and sexual intercourse in early adolescence. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1990;52:171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M. Dispelling myths and creating opportunity: A comparison of the strengths of single-parent and two-parent families. Advances in Nursing Science. 2000;23:41–58. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200009000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlmeier W, Granqvist P. Attachment transfer among Swedish and German adolescents: A prospective longitudinal study. Personal Relationships. 2006;13:261–279. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Cernkovich SA. Gender and antisocial behavior. In: Stoff DM, Breiling J, Maser JD, editors. Handbook of antisocial behavior. New York: Wiley; 1997. pp. 496–510. [Google Scholar]

- Garasky S, Meyer DR. Examining cross-state variation in the increase in father-only families. Population Research and Policy Review. 1998;17:479–495. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn TJ. From family to peer: A review of transitions of influence among drug-using youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1981;10:363–383. doi: 10.1007/BF02088939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AE. Introduction: Lesbian and gay parents and their children: Research and contemporary issues. In: Goldberg AE, editor. Lesbian and gay parents and their children: Research on the family life cycle. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gore S, Aseltine RH, Colton ME. Social structure, life stress, and depressive symptoms in a high school-aged population. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1992;33:97–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW, Botvin GJ, Scheier LM, Diaz T, Miller NL. Parenting practices as predictors of substance use, delinquency, and aggression among urban minority youth: Moderating effects of family structure and gender. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:174–184. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW, Botvin GJ, Scheier LM, Nichols TR. Factors associated with regular marijuana use among high school students: A long-term follow-up study. Substance Use and Misuse. 2002;37:225–238. doi: 10.1081/ja-120001979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggard-Grann U, Hallqvist J, Langstrom N, Moller J. The role of alcohol and learning disabilities association drugs in triggering criminal violence: A case-crossover study. Addiction. 2006;101:100–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemovich V, Crano W. Family structure and adolescent drug use: An exploration of single-parent families. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:2099–2113. doi: 10.3109/10826080902858375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Clingempeel WG. Coping with marital transitions: A family systems perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1992;57:1–242. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JP. The effects of family structure and family relations on adolescent marijuana use. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1995;30:1207–1241. doi: 10.3109/10826089509105131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JP. The community context of family structure and adolescent drug use. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2002;64:314–330. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Developmental Review. 1992;12:374–90. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. The socio-psychological framework. In: Jessor R, Jessor SL, editors. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1977. pp. 17–42. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2008 (NIH Publication No. 09-7401) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2009a. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2008. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Joslin CG, Minter SP. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender family law. New York: Thomson West; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Katz L, Gottman J. Buffering children from marital conflict and dissolution. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26:157–171. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2602_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. The parental and peer contexts of adolescent deviance: An algebra of interpersonal influences. Journal of Drug Issues. 1996;26:289–315. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Does marijuana use cause the use of other drugs? Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:482–483. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan D, Ferguson AJ. On the utilization of sample weights in latent variable models. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:305–321. [Google Scholar]

- Kopstein A, Crum RM, Celentano D, Martin S. Sensation seeking needs among 8th and 11th graders: Characteristics associated with cigarette and marijuana use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;62:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick JA, Judd CM. Transitions in social influences at adolescence: Who induces cigarette smoking? Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:359–368. [Google Scholar]

- Lac A, Crano WD. Monitoring matters: Meta-analytic review reveals the reliable linkage of parental monitoring with adolescent marijuana use. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2009;4:578–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Ceballo R, Abbey A, Stewart AJ. Does family structure matter? A comparison of adoptive, two-parent biological, single-mother, stepfather, and stepmother households. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:840–851. [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Feigelman S, Stanton B. Perceived parental monitoring and health risk behaviors among urban low-income African-American children and adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27:43–48. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Stanton B, Feigelman S. Impact of perceived parental monitoring on adolescent risk behavior over 4 years. Journal of Adolescent health. 2000;27:49–56. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist T. Cognitive consequences of cannabis use: Comparison with abuse of stimulants and heroin with regard to attention, memory, and executive functions. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2005;81:319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Coffey C, Degenhardt L. A longitudinal study of the effects of adolescent cannabis se on high school completion. Addiction. 2003;98:685–692. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Lamb KA. Adolescent well-being in cohabiting, married, and single-parent families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:876–893. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SK, Tilton-Weaver LC, Bosdet L. Information management: considering adolescents’ regulation of parental knowledge. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28:633–647. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell KA. Friends: The role of peer influence across adolescent risk behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31:267–277. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan SS. Father absence and the welfare of children. In: Hetherington EM, editor. Coping with divorce, single-parenting, and remarriage. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1999. pp. 177–145. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan SS, Sandefur GD. Growing up with a single-parent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty TL, Bellair PE. Explaining racial and ethnic differences in adolescent violence: Structural disadvantage, family well-being, and social capital. Justice Quarterly. 2003;20:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Miller N, Cowan P, Cowan C, Hetherington E, Clingempeel W. Externalizing in preschoolers and early adolescents: A cross-study replication of a family model. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Morral AR, McCaffrey DF, Chien S. Measurement of adolescent drug use. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:301–309. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson J, Phillips M, Peterson C, Battistutta D. Relationship between the parenting styles of biological parents and stepparents and the adjustment of young adult stepchildren. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage. 2002;36:57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson CJ. Parental sexual orientation, social science research, and child custody decisions. In: Galatzer-Levy RM, Kraus L, Galatzer-Levy J, editors. The scientific basis of child custody decisions. 2. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. pp. 285–306. [Google Scholar]

- Pendersen W, Mastekaasa A, Wichstrom L. Conduct problems and early cannabis initiation: A longitudinal study of gender differences. Addiction. 2001;96:415–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9634156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JR, Crano WD, Quist R, Burgoon M, Alvaro EM, Grandpre J. Acculturation, familism, parental monitoring, and knowledge as predictors of marijuana and inhalant use in adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:3–11. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin JH, Wells LE. Social control, broken homes, and delinquency. In: Barak G, editor. Varieties of criminology: Readings from a dynamic discipline. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1994. pp. 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Rueter MA, Keyes M, Iacono W, McGue M. Family interactions in adoptive compared to nonadoptive families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:58–66. doi: 10.1037/a0014091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld MJ. The age of independence: Interracial unions, same-sex unions, and the changing American family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In: von Eye A, Clogg CC, editors. Latent variables analysis: Applications for developmental research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 399–419. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel J, Alvaro E, Patel N, Crano W. “...you would probably want to do it. Cause that’s what made them popular”: Exploring perceptions of inhalant utility among young adolescent nonusers and occasional users. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:597–615. doi: 10.1080/10826080902809543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Daddis C. Domain-specific antecedents of parental psychological control and monitoring: the role of parenting beliefs and practices. Child Development. 2002;73:563–580. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder AR, McLaughlin DK, Findeis J. Household composition and poverty among female-headed households with children: Differences by race and residence. Rural Sociology. 2006;71:597–624. [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Comeau CA, Shepard SA. The relative contribution of sibling deviance and peer deviance in the prediction of substance use across middle childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:635–649. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000047212.49463.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. 2006 Retrieved July 7, 2008 from http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k6nsduh/2k6results.cfm#5.6.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings (NSDUH Series H-34, DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4343) Rockville, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Parent awareness of youth use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana. 2008 April 24; Retrieved July 7, 2008 from http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k8/parents/parents.htm.

- Sun Y. The well-being of adolescents in households with no biological parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:894–909. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland I, Shepard J. Social dimensions of adolescent substance use. Addiction. 2001;96:445–458. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9634458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson R. Gender differences in adolescent drug use: The impact of parental monitoring and peer deviance. Youth and Society. 2003;34:300–329. [Google Scholar]

- Swan AV, Melia RJW, Fitzsimons B, Breeze B, Murray M. Why do more girls than boys smoke cigarettes? Health Education Journal. 1988;48:59–64. doi: 10.1177/001789698804800205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman JB, Bentler PM. Structural equation modeling. In: Schinka JA, Velicer WF, editors. Handbook of psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2003. pp. 607–634. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Majority of children live with two biological parents. 2008a February 20; Retrieved July 7, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/PressRelease/www/releases/archives/children/011507.html.

- United States Census Bureau. Improvements to demographic household data in the current population survey: 2007. 2008b March 3; Retrieved July 7, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps08/twps08.pdf.

- Vandewater E, Lansford J. Influences of family structure and parental conflict on children’s well-being. Family Relations. 1998;47:323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein J, Lewis JM. Sibling outcomes and disparate parenting and stepparenting after divorce: Report from a 10-year longitudinal study. Psychoanalytic Psychology. 2007;24:445–458. [Google Scholar]

- Webb JA, Bray JH, Getz J, Adams G. Gender, perceived parental monitoring, and behavioral adjustment: Influences on adolescent alcohol use. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72:392–400. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westat. Wesvar 4.2, User’s Guide. Rockville: Westat; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Cleary SD. Validity of self-reports of smoking: Analyses by ethnicity in a sample of urban adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:56–61. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Resko JA, Ainette MG, Mendoza D. Role of parent support and peer support in adolescent substance use: A test of mediated effects. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:122–134. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. Parental, sibling, and peer influences on adolescent substance use and alcohol problems. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4:98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Stanton B, Cottrel L, Kaljee L, Galbraith J, Li X, Cole M, Harris C, Youniss J, Smollar J. Adolescent relations with mothers, fathers, and friends. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. Parental awareness of adolescent risk involvement: Implications of overestimates and underestimates. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Sensation seeking and crime, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]