Abstract

This paper characterizes N-benzyl-3-sulfonamidopyrrolidines (gyramides) as DNA gyrase inhibitors. Gyramide A was previously shown to exhibit antimicrobial activity, which suggested it inhibited bacterial cell division. In this study, we conducted target identification studies and identified DNA gyrase as the primary target of gyramide A. The gyramide A resistance-determining region in DNA gyrase is adjacent to the DNA cleavage gate and is a new site for inhibitor design. We studied the antibiotic effects of gyramides A−C in combination with the Gram-negative efflux pump inhibitor MC-207,110 (60 μM). The gyramides had a minimum inhibitory concentration of 2.5−160 μM against Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella enterica, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae; the compounds were ineffective against Enterococcus faecalis. The IC50 of gyramides A−C against E. coli DNA gyrase was 0.7−3.3 μM. The N-benzyl-3-sulfonamidopyrrolidines described in this manuscript represent a starting point for development of antibiotics that bind a new site in DNA gyrase.

Keywords: DNA gyrase, inhibitors, antibiotics, gyramides, 534F6

N-benzyl-3-sulfonamidopyrrolidine, which was previously referred to as “534F6”—now renamed gyramide A—was discovered in a cell-based screen to identify small molecules that inhibited E. coli division.1 Mukherjee et al. identified compounds that produced filamentous cells in an efflux pump deletion strain. (R)-Gyramide A induced cell filamentation, whereas (S)-gyramide A was a weak inhibitor of cell proliferation. These results suggested that (R)-gyramide A bound a specific intracellular target. In this paper we demonstrate that the target of this molecule is DNA gyrase.

DNA gyrase—a member of the family of type IIA topoisomerases—is an essential protein in bacteria that introduces negative supercoils in DNA via an ATP-dependent mechanism. The enzyme is an A2B2 tetramer consisting of GyrA and GyrB and its inhibition has catastrophic effects on cell proliferation and survival, which has made it an important target for the development of antibacterial agents.2−5 The DNA gyrase complex requires the transition between different conformational states to cleave duplex DNA, passage the DNA strand through the break, and religate the DNA fragments.3,6 The best-characterized class of inhibitors of DNA gyrase—the quinolones—inhibits supercoiling activity and induces double-strand breaks in DNA.2,3 The quinolones intercalate with bound DNA, contact both the GyrA and GyrB subunits, and stabilize the normally transient intermediate, consisting of cleaved DNA bound to DNA gyrase.7,8 Stabilization of the complex may release dsDNA breaks.9 New classes of type IIA topoisomerase inhibitors do not stabilize dsDNA breaks and are reported to inhibit the protein via a different mechanism.10−12 These inhibitors are therapeutically beneficial, as they can be used to inhibit the proliferation of strains of bacteria that are resistant to the quinolones.

Bacteria acquire resistance to quinolones by mutations to genes encoding DNA gyrase or topoisomerase IV.2,13,14 A single amino acid change in the genes coding these proteins produces low-level resistance to quinolones.13,15 One approach to transcend resistance is to develop classes of antibacterial drugs against new targets. The identification and exploitation of new targets for antibacterial development has numerous caveats, which have prevented the translation of many inhibitors into effective antibiotics.16,17 Recent studies support the reevaluation of DNA gyrase as a target for the development of new antibiotics.16 Inhibitors of DNA gyrase may be effective against a broad range of pathogens, bind to new sites in the protein, and inhibit via a mechanism that is different than that for the quinolones.10−12,18

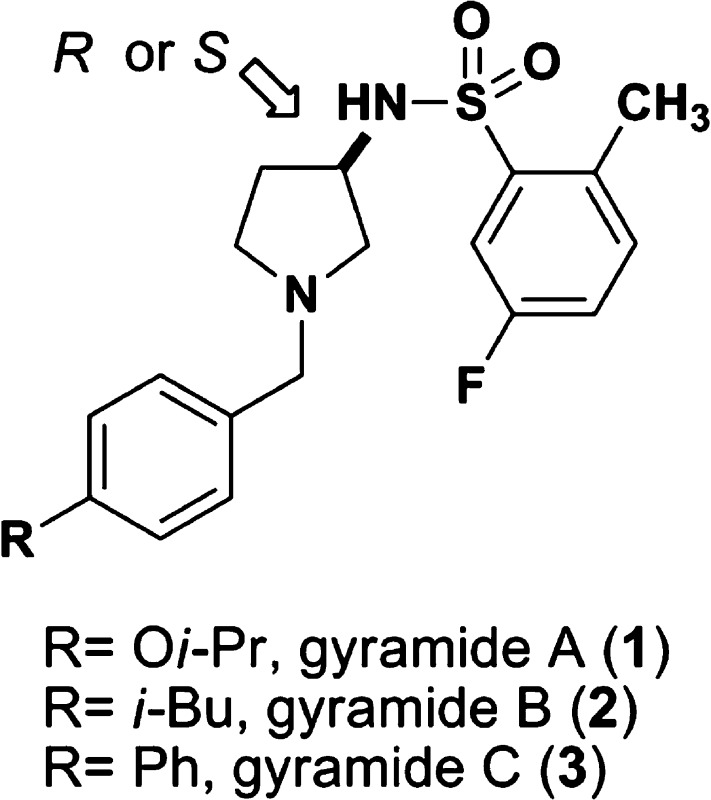

In this manuscript we demonstrate that gyramides A−C (1−3, Figure 1) inhibit DNA gyrase and we identify the location of the resistance-determining region in GyrA. We characterize the activity of 1−3 in vivo against a panel of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria and determine the activity of these inhibitors against E. coli DNA gyrase using an in vitro supercoiling assay. The results indicate that the N-benzyl-3-sulfonamidopyrrolidines are a new family of DNA gyrase inhibitors with potential for broad-spectrum antibiotic development.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of gyramides 1−3. The arrow indicates the chiral center in the gyramides.

In an effort to identify the target of the gyramides, we prepared affinity reagents to pull-down the protein target of 1 (see Supporting Information for full experimental details); we also screened for bacterial variants resistant to 1. Unfortunately, we were unable to determine the target protein using the affinity method, but we were successful in obtaining bacteria resistant to 1. Compound 1 had no effect on the growth of the wild type E. coli K-12 BW25113, so we isolated spontaneous resistant mutants of this compound using the ΔtolC strain from the Keio collection.19 The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 1 against E. coli BW25113 ΔtolC was 10 μM; in this strain the AcrAB-TolC multidrug efflux pump is not functional. We isolated 35 spontaneous resistant mutants of this strain from colonies growing on plates infused with 1 (at a concentration of 50 μM, or 5× the MIC value for this strain). Two mutants were deep sequenced. Analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms in E. coli BW25113 and the isolated mutants revealed a single nucleotide substitution in the gyrA open reading frame of each mutant, which encodes GyrA. Both mutations result in amino acid changes to GyrA (Leu34Gln and Gly170Cys) and are unique sites that have not been previously described as conferring cell resistance to DNA gyrase inhibitors. This result suggests that 1 targets DNA gyrase via binding to a new region of the active site.

A GyrA mutant (Leu98Gln) resistant to 1 had the same sensitivity to ciprofloxacin as the ΔtolC background strain (5 nM). The inhibitory mechanisms of the quinolones and 1 are thus different, as there is no development of cross-resistance. Gyramides A−C therefore represent a new class of antibacterial agents. To further validate that the resistance-determining region of 1−3 does not overlap with other known DNA gyrase inhibitors, we sequenced the gyrA and gyrB open reading frames of the remaining 33 mutants.

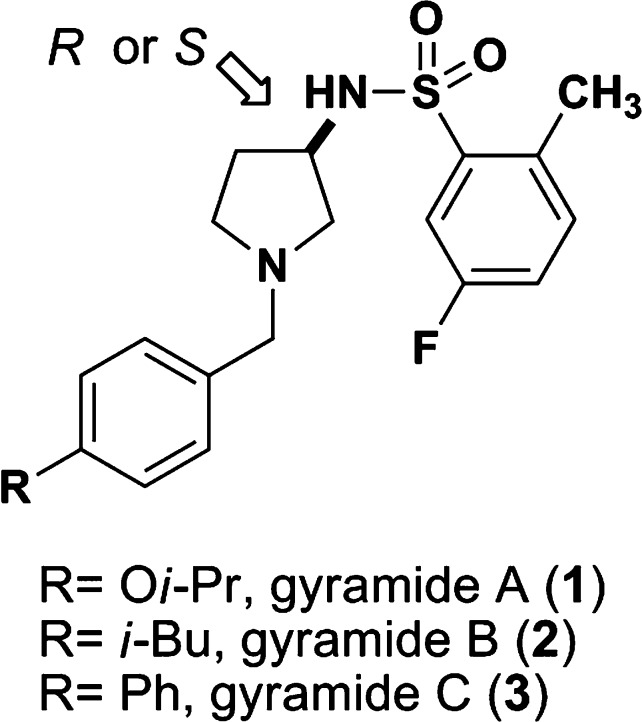

Each mutant carried a single nucleotide change in gyrA or gyrB that resulted in an amino acid alteration. We identified 16 different single nucleotide changes, which was consistent with a rate of 3.77 × 10−9 per generation (95% confidence interval 4.96, 2.71), at which first-step spontaneous mutants of 1 emerged in our screen. The spontaneous mutations that convey resistance to the strain E. coli BW25113 ΔtolC cluster in a region adjacent to the DNA cleavage/relegation site. Table S1 of the Supporting Information lists the amino acid changes that we identified for strains resistant to 1. Figure 2 illustrates the region of GyrA and GyrB that conveys resistance to 1, the active site tyrosine, and the quinolone resistance-determining region mapped on the crystal structure. Several of the GyrA mutations are in appropriate positions to contact the phosphate backbone of the bound DNA. It is possible that these mutations affect the binding of DNA to gyrase, which may perturb the position of the DNA duplex and occlude the binding site. The gyramides may also make contacts with both GyrA and GyrB subunits as well as with bound DNA, which would be analogous to the quinolones.8,10 In this case, a change in position of the DNA duplex may affect binding of gyramides to GyrA and GyrB. The loci we identified do not overlap with mutations that have been reported in bacteria resistant to quinolones13 and recently described inhibitors.10,11 We evaluated the antibacterial properties of 1−3 to assess their activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial pathogens.

Figure 2.

Location of amino acids that confer resistance to 1. The E. coli DNA gyrase structure from ref (22) (PDB 3NUH). The cartoon shows the GyrA subunit in beige, the GyrB subunit in gray, and the DNA duplex with the backbone and bases represented by lines. The DNA duplex was modeled to the structure by alignment of the GyrA subunit to the structure from ref (10) (PDB 2XCS). The atoms of several different amino acid side chains are displayed as colored spheres. The active-site tyrosine is green, amino acids that were identified in mutants that are resistant to quinolones are red, and amino acids that confer resistance to 1 are blue. The image was generated using PyMol.23

MC-207,110 is an inhibitor of resistance−nodulation−division family efflux pumps and has been a useful tool for improving the activity of quinolone antibiotics in bacteria that express efflux pumps.20,21 For assessing the antibacterial properties of 1−3, we found it necessary to use MC-207,110 with E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. enterica. The MIC values we measured for 1−3 against several different genera of bacteria are tabulated in Table 1. We chose a combination of 1 and MC-207,110 that minimized the concentration of both compounds while maximizing the potency of 1−3 (see Figure S1).

Table 1. MICs of Gyramides (R)-1, 2, and 3 and (S)-1a.

| bacterial strain | (R)-1 | 2 | 3 | (S)-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli BW25113 ΔtolC | 10 | 5 | 2.5 | 140 |

| E. coli BW25113 + 60 μM MC-207,110 | 40 | 40 | 20 | ND |

| P. aeruginosa K + 60 μM MC-207,110 | 80 | 40 | 20 | ND |

| S.enterica ATCC 19585 + 60 μM MC-207,110 | 80 | 20 | 10 | ND |

| S. aureus FRI 100 | >160 | 80 | 20 | ND |

| S.pneumoniae ATCC 10813 | 160 | 20 | 10 | ND |

| E.faecalis 1131 | >160 | >160 | >160 | ND |

The MICs of the gyramides were determined for the drug pump knockout strain E. coli BW25113 ΔtolC. We used 60 μM drug pump inhibitor MC-207,110 with the wild type strains E. coli BW25113, P. aeruginosa K, and S. enterica ATCC 19585 to potentiate the activity of the compounds. The susceptibility of the wild type strains of S. aureus FRI100, S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813, and E. faecalis 1131 without a pump inhibitor are shown. The label “ND” indicates data that we did not collect, as the activity of (S)-1 was low against E.coli BW25113 ΔtolC. The values in the table are reported in μM concentrations.

Multidrug resistance pumps also confer resistance of Gram-positive bacterial strains to fluoroquinolones.20,21 NorA in S. aureus can provide resistance to fluoroquinolones, which can be suppressed with the addition of reserpine.20 The treatment of cells with reserpine, however, did not potentiate the activity of 1−3 against S. aureus (see Figure S1); all combinations of 1−3 with and without reserpine were ineffective against E. faecalis. Based on this data, it is unlikely that the major facilitator family efflux-pumps found in these strains are responsible for differences in the activity of 1−3 in Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains. The S. pneumoniae and E. faecalis GyrA protein sequences are 69% identical and only differ by one residue in the gyramide resistance conferring region that we identified. In E. faecalis and E. coli, position 96 (E. coli numbering) contains phenylalanine; in S. pneumoniae, this position is occupied by tryptophan. As S. pneumoniae is sensitive to the gyramides, it is possible that differences in membrane permeability and efflux may explain the insensitivity of E. faecalis to this class of compounds. This property of E. faecalis may be advantageous, as this species is part of normal gut flora and is often nonpathogenic.

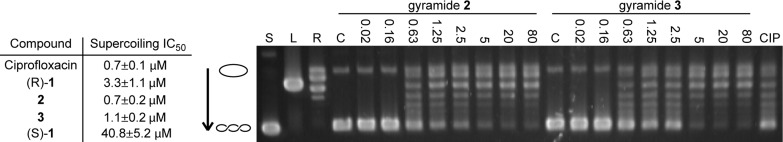

In addition to determining the antibacterial properties of 1−3, we analyzed their effect on E. coli DNA gyrase in vitro and compared the data to those for ciprofloxacin. We performed in vitro supercoiling activity assays to determine the IC50 values for 1−3. Figure 3 demonstrates a representative gel from one of the assays and a table containing the IC50 values obtained for each compound. We determined that (R)-1 inhibits the in vitro supercoiling activity of E. coli DNA gyrase with an IC50 of 3.3 ± 1.0 μM, whereas the IC50 of (S)-1 was 40.8 ± 5.2 μM. The difference in activity in vitro agrees with the observation that (R)-1 is a more potent antibiotic than (S)-1 and confirms that the compounds bind a specific site on DNA gyrase. Compounds 2 and 3 had improved activity over 1 in vitro, with an IC50 of 0.7 ± 0.2 μM and 1.1 ± 0.2 μM, respectively. By comparison, ciprofloxacin had an IC50 of 0.7 ± 0.1 μM in our assay. Ciprofloxacin and 2 have a similar effect on DNA gyrase supercoiling activity yet significant differences in antimicrobial activity. Against E. coli BW25113 ΔtolC, the MIC of 2 is 5 μM, whereas the MIC for ciprofloxacin is 5 nM. We sought to determine the differences that explain the disparity.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of DNA gyrase supercoiling activity by 1−3. The table summarizes the IC50 values for ciprofloxacin and gyramides (R)-1, 2, 3, and (S)-1. A representative gel obtained from the analysis of the inhibition of DNA gyrase supercoiling activity is shown. The open circle graphic represents relaxed closed circular DNA, the coiled graphic signifies supercoiled DNA, and the arrow shows the direction of increased mobility of supercoiled DNA states. Supercoiled (“S”), linear (“L”), and relaxed (“R”) pUC19 controls are labeled above the lanes. Gel data for assays with 2 and 3 are shown (in μM); the label “C” indicates the lane for the solvent control. The lane labeled “CIP” represents treatment with 0.7 μM ciprofloxacin, which is the IC50 for ciprofloxacin in our assay.

Ciprofloxacin induces the formation of dsDNA breaks in DNA bound to DNA gyrase in vitro by stabilizing the intermediate in which the DNA backbone is covalently linked to tyrosine. When detergent is added to the reaction, the DNA gyrase complex dissociates, leaving dsDNA breaks covalently attached to GyrA. GyrA can be enzymatically cleaved away from the linear DNA, which can be distinguished from closed, circular DNA on a gel. In our assay, we observed the production of dsDNA breaks with the addition of ciprofloxacin. Increasing the concentration of 1 (≤3.3 mM) did not generate linearized DNA in our assay (see Figure S2 of the Supporting Information). The recently reported DNA gyrase inhibitor NXL101 binds E. coli and S. aureus DNA gyrase in vitro and also does not release dsDNA ends.11 Interestingly, NXL101 is a more potent antibiotic and inhibitor of DNA gyrase supercoiling activity in S. aureus than ciprofloxacin.11 The gyramides and ciprofloxacin are similar in their inhibition of the supercoiling activity of DNA gyrase; however, only ciprofloxacin creates DNA damage in vitro with E. coli DNA gyrase. These results suggest that 1−3 inhibit DNA gyrase in vitro via a mechanism that is different from those of the fluoroquinolone antibiotics. The disparity in the antimicrobial activity that we observe for these two classes of compounds may be explained by differences in the production of DNA damage in the cell.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that a previously unidentified region of DNA gyrase, which can be targeted by small molecules, exists adjacent to the DNA gate in GyrA. The evidence is consistent with compounds 1−3 binding to this region of GyrA and inhibiting the protein; these compounds are effective antibiotics against Gram-negative bacteria when paired with an efflux pump inhibitor and against some Gram-positive bacteria. Compounds 1−3 could act as model compounds for the development of antibiotics that inhibit this previously unexplored region of DNA gyrase, which may be useful in treating multidrug resistant infections. This new mode of inhibition for DNA gyrase may be utilized in the development of therapeutic agents that will not be subject to cross-resistance with quinolone antibiotics.

Acknowledgments

E. coli BW25113 and single gene mutants from the Keio collection were gifts from the National BioResource Project (NIG, Japan).

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures for the synthesis and characterization of affinity reagents 13−15, procedures for the isolation and characterization of spontaneous mutants, and the determination of MIC and IC50 values. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The Shaw Lab acknowledges funding from NIH/AID (R56AI80931). The Weibel Lab acknowledges funding from DARPA, the Human Frontier Science Program (RGY0069/2008-C), USDA (WIS01366), the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, and a Searle Scholar Award.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Mukherjee S.; Robinson C. A.; Howe A. G.; Mazor T.; Wood P. A.; Urgaonkar S.; Herbert A. M.; RayChaudhuri D.; Shaw J. T. N-Benzyl-3-sulfonamidopyrrolidines as novel inhibitors of cell division in E. coli. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 6651–6655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrega A.; Madurga S.; Giralt E.; Vila J. Mechanism of action of and resistance to quinolones. Microbial Biotechnol. 2009, 2, 40–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drlica K.; Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1997, 61, 377–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers C. L. F.; Oberthuer M.; Heide L.; Kahne D.; Walsh C. T. Assembly of Dimeric Variants of Coumermycins by Tandem Action of the Four Biosynthetic Enzymes CouL, CouM, CouP, and NovN. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 15022–15036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell A. DNA gyrase as a drug target. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1999, 27, 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral J. H. M.; Jackson A. P.; Smith C. V.; Shikotra N.; Maxwell A.; Liddington R. C. Crystal structure of the breakage-reunion domain of DNA gyrase. Nature 1997, 388, 903–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz F. J.; Higgins P. G.; Mayer S.; Fluit A. C.; Dalhoff A. Activity of quinolones against gram-positive cocci: mechanisms of drug action and bacterial resistance. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2002, 21, 647–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H.; Bogaki M.; Nakamura M.; Yamanaka L. M.; Nakamura S. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrB gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991, 35, 1647–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohanski M. A.; Dwyer D. J.; Collins J. J.. How antibiotics kill bacteria: from targets to networks. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 423−435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax B. D.; Chan P. F.; Eggleston D. S.; Fosberry A.; Gentry D. R.; Gorrec F.; Giordano I.; Hann M. M.; Hennessy A.; Hibbs M.; Huang J.; Jones E.; Jones J.; Brown K. K.; Lewis C. J.; May E. W.; Saunders M. R.; Singh O.; Spitzfaden C. E.; Shen C.; Shillings A.; Theobald A. J.; Wohlkonig A.; Pearson N. D.; Gwynn M. N. Type IIA topoisomerase inhibition by a new class of antibacterial agents. Nature 2010, 466, 935–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black M. T.; Stachyra T.; Platel D.; Girard A. M.; Claudon M.; Bruneau J. M.; Miossec C. Mechanism of action of the antibiotic NXL101, a novel nonfluoroquinolone inhibitor of bacterial type II topoisomerases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 3339–3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener J. J. M.; Gomez L.; Venkatesan H.; Alejandro Santillan J.; Allison B. D.; Schwarz K. L.; Shinde S.; Tang L.; Hack M. D.; Morrow B. J.; Motley S. T.; Goldschmidt R. M.; Shaw K. J.; Jones T. K.; Grice C. A. Tetrahydroindazole inhibitors of bacterial type II topoisomerases. Part 2: SAR development and potency against multidrug-resistant strains. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 2718–2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz J. Mechanisms of resistance to quinolones: target alterations, decreased accumulation and DNA gyrase protection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 51, 1109–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren P. K.; Karlsson A.; Hughes D. Mutation Rate and Evolution of Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Escherichia coli Isolates from Patients with Urinary Tract Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 3222–3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H.; Bogaki M.; Nakamura M.; Nakamura S. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrA gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1990, 34, 1271–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne D. J.; Gwynn M. N.; Holmes D. J.; Pompliano D. L. Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nature Rev. Drug Discovery 2007, 6, 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz A. B.; Hoover J. L.; Payne D. J. Antibacterial Drug Discovery in the Age of Resistance. Microbe 2010, 5, 390–396. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez L.; Hack M. D.; Wu J.; Wiener J. J. M.; Venkatesan H.; Alejandro Santillan J.; Pippel D. J.; Mani N.; Morrow B. J.; Motley S. T.; Shaw K. J.; Wolin R.; Grice C. A.; Jones T. K. Novel pyrazole derivatives as potent inhibitors of type II topoisomerases. Part 1: Synthesis and preliminary SAR analysis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 2723–2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T.; Ara T.; Hasegawa M.; Takai Y.; Okumura Y.; Baba M.; Datsenko K. A.; Tomita M.; Wanner B. L.; Mori H. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006, 2, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomovskaya O.; Watkins W. Inhibition of efflux pumps as a novel approach to combat drug resistance in bacteria. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 3, 225–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M. L. Modulation of Antibiotic Efflux in Bacteria. Curr. Med. Chem. 2002, 1, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeffler A. J.; May A. P.; Berger J. M.. A domain insertion in Escherichia coli GyrB adopts a novel fold that plays a critical role in gyrase function; Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 7830−7844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrodinger, LLC. (2010) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3r1.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.