Abstract

Using time-kill methodology, we investigated the interactions of fosfomycin with meropenem or colistin or gentamicin against 17 genetically distinct Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates carrying blaKPC-2. Synergy was observed with meropenem or colistin against 64.7 and 11.8% of tested isolates, while the combination with gentamicin resulted in indifference. All studied combinations showed improved bactericidal activity, compared to fosfomycin alone and prevented the development of fosfomycin resistance in 69.2, 53.8, and 81.8% of susceptible isolates, respectively.

INTRODUCTION

Fosfomycin is a phosphonic acid derivative (cis-1,2-epoxypropylphosphonic acid) with a broad spectrum of activity against various Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase- and/or carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, even those that are tigecycline or colistin nonsusceptible (4, 5, 6). Unfortunately, resistance develops rapidly when fosfomycin is used as monotherapy (3); therefore, combinations with other antimicrobials are preferred in clinical practice for the treatment of serious infections. Nevertheless, the potential advantage of such combinations against the multiresistant Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing bacteria predominant nowadays has not yet been studied.

(Part of these data was presented at the 47th Infectious Diseases Society of America Annual Meeting, 2009, Philadelphia, PA [abstr. 218].)

We investigated the in vitro activities of fosfomycin and meropenem, gentamicin, or colistin alone and in combination against 17 unique clinical isolates of KPC-2-producing K. pneumoniae isolated from inpatients at the University General Hospital Attikon, Athens, Greece. MICs were determined using the BD Phoenix automated system (Becton Dickinson Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD). Those of meropenem (Dianippon Sumitomo Pharma, Osaka, Japan) and fosfomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were also evaluated with agar dilution (2), and those of colistin (sulfate salt, AppliChem GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) were also evaluated with the Etest (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden). Results were interpreted in accordance with CLSI criteria (2), except for fosfomycin and colistin, for which the susceptibility breakpoints proposed by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (www.eucast.org) were used (≤32 μg/ml for fosfomycin and ≤2 μg/ml for colistin). All isolates were screened for the production of a KPC enzyme with the imipenem-boronic acid disk synergy test (15), PCR using primers specific for blaKPC (1), and sequencing (Eurofins MWG GmbH, Ebersberg, Germany). On the basis of these tests, all of the isolates studied carried blaKPC-2. The genetic relatedness of these isolates was evaluated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis of chromosomal restriction fragments obtained after SpeI cleavage (14). In vitro interactions between fosfomycin and meropenem or gentamicin (AppliChem) or colistin were tested using time-kill methodology (13) in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton II broth (Becton Dickinson) supplemented with 25 μg/ml glucose-6-phosphate (AppliChem), which was required for induction of the transport system of hexose monophosphate necessary for the entry of fosfomycin into bacterial cells (2). The antibiotic concentrations used were 100 μg/ml for fosfomycin, 10 μg/ml for meropenem, and 5 μg/ml for colistin and gentamicin, as these concentrations represent the steady state of the respective antibiotic achievable in human serum during treatment (7, 10, 11). The lower limit of detection was 1.6 log10 CFU/ml. Synergy, antagonism, indifference, and bactericidal activity were defined as previously reported (13). Fisher's exact test was used to compare proportions of killing activity in two-by-two tables. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. In order to evaluate the development of resistance to fosfomycin as a reason for bacterial regrowth after 24 h of incubation with fosfomycin alone or in combination, viable colonies were submitted to susceptibility testing in comparison with the respective wild-type strain using agar dilution. This evaluation was performed only for isolates that were initially susceptible to fosfomycin.

The results are depicted in Table 1. These strains were collected from September 2007 until July 2009 during an outbreak of KPC-2 producing K. pneumoniae in our institution. Four major clonal types were identified by PFGE during this outbreak (12). Strains representative of all four clonal types were evaluated in the present study. Multiple isolates of the most common subtypes (A1, A2, and B1) were included because of differences in the susceptibility phenotype or the bla gene content of the isolates (data not shown). The clonal nature of the KPC-producing K. pneumoniae outbreak in our hospital precluded from testing a larger number of isolates that were genotypically diverse.

Table 1.

Clonal types of the 17 KPC-2-positive K. pneumoniae isolates studied, MICs of fosfomycin, meropenem, colistin, and gentamicin, ratio of the concentration of each antibiotic used in time-kill studies to the MIC, and in vitro interactions of the combinations tested against these isolates

| Strain | Clonal type | MIC (μg/ml), ratio of concn testeda to MIC |

Interactionb of FOF with (growth time[s] [h]): |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fosfomycin | Meropenem | Colistin | Gentamicin | Meropenem | Colistin | Gentamicin | ||

| m 4096C | C | 8, 12.5 | 4, 2.5 | 0.75, 6.67 | >8, <0.61 | Ind | Ind | Ind |

| 439 CII | A2 | 8, 12.5 | 64, 0.16 | 0.38, 13.16 | ≤2, ≥2.5 | Syn (24) | Ind | Ind |

| m 4908C | D | 16, 6.25 | 64, 0.16 | 32, 0.16 | ≤2, ≥2.5 | Syn (24) | Ind | Ind |

| b 1013 | A2 | 16, 6.25 | 64, 0.16 | 0.38, 13.16 | 4, 1.25 | Syn (24) | Ind | Ind |

| P 908 | A1 | 16, 6.25 | 32, 0.31 | 12, 0.42 | ≤2, ≥2.5 | Syn (24) | Syn (24) | Ind |

| 258 | A1 | 16, 6.25 | 64, 0.16 | 8, 0.63 | ≤2, ≥2.5 | Syn (24) | Ind | Ind |

| 202 | A1 | 16, 6.25 | 32, 0.31 | 48, 0.10 | ≤2, ≥2.5 | Syn (24) | Ind | Ind |

| P 903 | A1 | 32, 3.13 | 32, 0.31 | 16, 0.31 | 4, 1.25 | Syn (6, 24) | Syn (6) | Ind |

| m 538C | A2 | 32, 3.13 | 128, 0.08 | 0.38, 13.16 | 8, 0.61 | Ind | Ind | Ind |

| m 2573A | A1 | 32, 3.13 | 8, 1.25 | 6, 0.83 | >8, <0.61 | Ind | Ind | Ind |

| m 4185C | B1 | 32, 3.13 | 32, 0.31 | 0.5, 10 | ≤2, ≥2.5 | Syn (24) | Ind | NDc |

| m 4362C | B1 | 32, 3.13 | 64, 0.16 | 0.38, 13.16 | ≤2, ≥2.5 | Syn (24) | Ind | Ind |

| m 3353 | B1 | 32, 3.13 | 32, 0.31 | 0.75, 6.67 | ≤2, ≥2.5 | Syn (24) | Ind | ND |

| m 1044C | A2 | 256, 0.39 | >256, <0.04 | 24, 0.21 | 4, 1.25 | Ind | Ind | Ind |

| 608 | A2 | 256, 0.39 | >256, <0.04 | 4, 1.25 | ≤2, ≥2.5 | Ind | Ind | Ind |

| 878 P | A2 | 256, 0.39 | 256, 0.04 | 0.5, 10 | ≤2, ≥2.5 | Ind | Ind | Ind |

| m 3473C | B2 | >256, <0.39 | 8, 1.25 | 1, 5 | >8, <0.61 | Syn (24) | Ind | Ind |

The antibiotic concentrations used in time-kill studies were as follows: fosfomycin, 100 μg/ml; meropenem, 10 μg/ml; colistin and gentamicin, 5 μg/ml. The MICs (μg/ml) for 50 and 90%, respectively, of the isolates studied (percent susceptible) were as follows: fosfomycin, 32 and 256 (76.5); meropenem, 64 and >256 (5.9); colistin, 1 and 32 (52.9); gentamicin, ≤2 and >8 (76.5).

Ind, indifference; Syn, synergy. The number (%) of isolates showing synergy/total number of isolates was as follows: meropenem, 11/17 (64.7%);colistin, 2/17 (11.8%); gentamicin, 0/15 (0%). The number (%) of isolates in which resistance to fosfomycin was prevented (the denominator is the number of fosfomycin-susceptible isolates tested) was as follows: meropenem, 9/13 (69.2%); colistin, 7/13 (53.8%); gentamicin, 9/11 (81.8%).

ND, not done.

The combination of fosfomycin and meropenem exhibited synergy against 11 (64.7%) of the 17 isolates. This combination was bactericidal against 12 (70.6%) of the 17 isolates, 11 of which were susceptible to fosfomycin (bactericidal activity of the combination versus that of fosfomycin or meropenem alone, P < 0.05). The combination of fosfomycin and colistin was synergistic against 2 (11.8%) of the 17 isolates and exhibited bactericidal activity against 11 (64.7%) of them. All of these isolates were colistin susceptible, with the exception of two (608 and P 908) (P < 0.05 for the bactericidal activity of the combination versus that of fosfomycin and P = 0.3 versus that of colistin alone).

The combination of fosfomycin and gentamicin exhibited an indifferent effect against all of the isolates tested and was not able to suppress the growth of any of the gentamicin-resistant isolates. It was bactericidal against all of the gentamicin-susceptible and intermediately gentamicin-susceptible ones (12 of 15, 80%) (P < 0.05 for the bactericidal activity of the combination versus that of fosfomycin alone and P = 1.0 versus that of gentamicin alone).

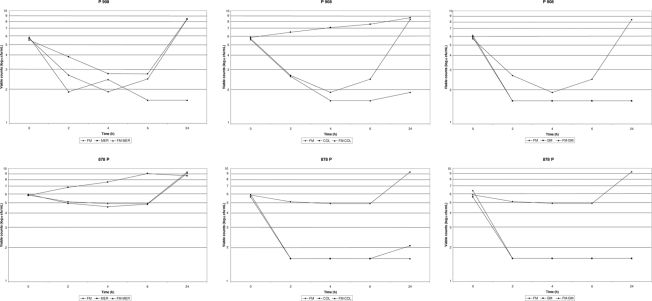

Representative time-kill curves are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Time-kill studies showing interactions of fosfomycin (FM) with meropenem (MER), colistin (COL), or gentamicin (GM) against two representative isolates (P 908 and 878 P) included in the present study.

Repeat MIC determination was done for 13 K. pneumoniae isolates that were initially susceptible to fosfomycin. All isolates developed resistance to fosfomycin after 24 h of incubation with fosfomycin alone. A clone resistant to fosfomycin was selected in 4 isolates (4/13, 30.8%) after incubation with fosfomycin and meropenem and in 6 isolates (6/13, 46.2%) after incubation with fosfomycin and colistin. The latter were all colistin-resistant isolates. In 2 isolates (2/11, 18.2%), a clone resistant to fosfomycin was selected after incubation with fosfomycin and gentamicin. These isolates were all gentamicin resistant.

Clinical studies have shown that combinations with fosfomycin achieved an overall cure rate of >80% against serious infections caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens, but data specifically concerning KPC producers are scarce. Recently, fosfomycin was administered to 11 seriously ill intensive care unit patients in combination with colistin or gentamicin and resulted in a successful clinical response in all of them (8). Fosfomycin in combination with a carbapenem was evaluated against 18 ertapenem-nonsusceptible Escherichia coli and K. pneumoniae clinical isolates, none of which carried blaKPC. An additive effect and a ca. 2-fold reduction of the carbapenem MIC were noted (9). Fosfomycin combinations have not been previously evaluated against KPC-producing K. pneumoniae. Our experiments showed that fosfomycin resulted in synergy with meropenem or colistin against 64.7 and 11.8% of isolates, respectively. All of the combinations studied showed improved bactericidal activity compared to fosfomycin alone and prevented the development of fosfomycin resistance in the majority of susceptible isolates.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 February 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bradford P. A., et al. 2004. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella species possessing the class A carbapenem-hydrolysing KPC-2 and inhibitor-resistant TEM-30 beta lactamases in New York City. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. CLSI. 2009. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 19th informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S19. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ellington M. J., Livermore D. M., Pitt T. L., Hall L. M., Woodford N. 2006. Mutators among CTX-M β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and risk for the emergence of fosfomycin resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:848–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Endimiani Α., et al. 2010. In vitro activity of fosfomycin against blaKPC-containing Klebsiella pneumonia isolates, including those nonsusceptible to tigecycline and/or colistin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:526–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Falagas M. E., Kastoris A. C., Kapaskelis A. M., Karageorgopoulos D. E. 2010. Fosfomycin for the treatment of multidrug-resistant, including extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing, Enterobacteriaceae infections: a systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Falagas M. E., et al. 2010. Antimicrobial susceptibility of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Enterobacteriaceae isolates to fosfomycin. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35:240–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li J., et al. 2003. Steady-state pharmacokinetics of intravenous colistin methanesulphonate in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:987–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Michalopoulos A., et al. 2010. Intravenous fosfomycin for the treatment of nosocomial infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in critically ill patients: a prospective evaluation. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:184–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Netikul T., Leelaporn A., Leelarasmee A., Kiratisin P. 2010. In vitro activities of fosfomycin and carbapenem combinations against carbapenem non-susceptible Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35:609–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nicolau D. P. 2008. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of meropenem. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47(Suppl. 1):32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pfausler B., et al. 2004. Concentrations of fosfomycin in the cerebrospinal fluid of neurointensive care patients with ventriculostomy-associated ventriculitis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:848–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Souli M., et al. 2010. An outbreak of infection due to b-lactamase Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase 2-producing K. pneumoniae in a Greek university hospital: molecular characterization, epidemiology, and outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:364–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Souli, et al. 2009. Does the activity of the combination of imipenem and colistin in vitro exceed the problem of resistance in metallo-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2133–2135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tenover F. C., et al. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tsakris A., et al. 2009. Use of boronic acid disk tests to detect extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in clinical isolates of KPC carbapenemase-possessing Enterobacteriaceae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3420–3426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]