Abstract

The aim of this study was to assess the in vitro activities of nemonoxacin (a novel nonfluorinated quinolone), doripenem, tigecycline, and 16 other antimicrobial agents against Nocardia species. The MICs of the 19 agents against 151 clinical isolates of Nocardia species were determined by the broth microdilution method. The isolates were identified to the species level using 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis. The results showed that N. brasiliensis (n = 60; 40%) was the most common species, followed by N. cyriacigeorgica (n = 24; 16%), N. farcinica (n = 12; 8%), N. beijingensis (n = 9), N. otitidiscaviarum (n = 8), N. nova (n = 8), N. asiatica (n = 7), N. puris (n = 6), N. flavorosea (n = 5), N. abscessus (n = 3), N. carnea (2), and one each of N. alba, N. asteroides complex, N. rhamnosiphila, N. elegans, N. jinanensis, N. takedensis, and N. transvalensis. The MIC90s of the tested quinolones against the N. brasiliensis isolates were in the order nemonoxacin = gemifloxacin < moxifloxacin < levofloxacin = ciprofloxacin, and the MIC90s of the tested carbapenems were in the order doripenem = meropenem < ertapenem < imipenem. Tigecycline had a lower MIC90 (1 μg/ml) than linezolid (8 μg/ml). The MIC90s of the tested quinolones against N. cyriacigeorgica isolates were in the order nemonoxacin < gemifloxacin < moxifloxacin < levofloxacin < ciprofloxacin, and the MIC90s of the tested carbapenems were in the order imipenem < doripenem = meropenem < ertapenem. Nemonoxacin had the lowest MIC90 values among the tested quinolones against the other 17 Nocardia isolates. Among the four tested carbapenems, imipenem had the lowest MIC90s. All of the clinical isolates of N. beijingensis, N. otitidiscaviarum, N. nova, and N. puris and more than half of the N. brasiliensis and N. cyriacigeorgica isolates were resistant to at least one antimicrobial agent. The results of this in vitro study suggest that nemonoxacin, linezolid, and tigecycline are promising treatment options for nocardiosis. Further investigation of their clinical role is warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Nocardia species, soilborne aerobic actinomycetes with worldwide distribution, can cause local or disseminated infection in humans, especially in immunocompromised individuals (3, 15, 17, 20). Pulmonary nocardial infection can be caused by N. abscessus, N. cyriacigeorgica, N. farcinica, and N. nova; in contrast, N. brasiliensis was the most common pathogen associated with primary skin infection (mycetoma) (3, 20). This group of organisms is rapidly expanding and now comprises at least 80 species (http://www.bacterio.cict.fr/n/nocardia.html). Traditional identification of Nocardia to the species level is based on microscopic morphology and phenotypic characteristics; however, those methods are cumbersome and cannot accurately identify newer species. Since Nocardia species differ in the clinical spectrum of diseases they cause and their susceptibilities to antibiotics, it is important to precisely identify Nocardia isolates beyond the genus level. Molecular methods, such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis, allow more accurate identification and the elucidation of taxonomy, such as the former N. asteroides complex isolates, which, after the use of modern molecular methods, were further identified as distinct species/taxa of Nocardia with different antimicrobial susceptibility patterns (3). Therefore, final confirmation of Nocardia species should be done by molecular techniques after initial identification. Only after correct identification of Nocardia species can the antibiotic susceptibilities of these organisms be understood.

Sulfonamide antibiotics have been used to treat nocardiosis since the 1940s and remain the most common type of antimicrobial used to treat these infections (1, 8, 24). However, a retrospective evaluation of the antibiotic resistance patterns of 765 Nocardia isolates in the United States during the period 1995 to 2004 showed that 61% of the isolates were resistant to sulfamethoxazole (SMZ) and 42% were resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ) (23). In addition, the only alternatives to sulfa-based antibiotics are amoxicillin-clavulanate, imipenem (IMP), and amikacin (25). Thus, it is important to identify additional alternative antimicrobials and to perform in vitro susceptibility testing with these agents to evaluate their activities against Nocardia isolates.

Nemonoxacin (TG-873870), a nonfluorinated quinolone (NFQ), differs from other fluoroquinolones in that it lacks the fluorine in the R6 position. Nemonoxacin retains potent broad-spectrum activities against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (6, 19). This study compared the susceptibilities of different Nocardia species to 19 antimicrobials, including three newly available agents (doripenem, tigecycline, and nemonoxacin).

(Some of the results were reported in our previous study [10]. Part of MIC data for amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, imipenem, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, sulfamethoxazole, and amikacin was reported previously [14].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

All of the clinical isolates of Nocardia species were collected from patients treated in four large medical centers in Taiwan from 1998 to 2009. These hospitals were National Taiwan University Hospital (2,500 beds), National Cheng Kung University Hospital (1,200 beds), Chi-Mei Medical Center (1,500 beds), and Kaohsiung Medical University Chung-Ho Memorial Hospital (1,700 beds). Identification of the isolates was based on positive Gram stain (Gram-positive branching, beaded, and filamentous bacilli), positive modified acid-fast stain results, colonial morphotypes, and conventional biochemical reactions, including hydrolysis of casein, xanthine, hypoxanthine, and tyrosine. The identities of the clinical isolates were further confirmed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis as previously described (20). Partial sequencing analysis of the 16S rRNA gene was performed using the primers Noc1 (5′-GCTTAACACATGCAAGTCG-3′) (positions 46 to 64; Escherichia coli numbering system) and Noc2 (5′-GAATTCCAGTCTCCCCTG-3′) (positions 663 to 680; E. coli numbering system) (20). The sequences were compared with published sequences in the GenBank database. The closest matches and GenBank accession numbers were obtained.

Susceptibility testing.

The MICs of the 19 tested drugs, i.e., SMZ, ceftriaxone (CRO), and vancomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO); azithromycin and linezolid (LZD) (Pfizer Inc., New York, NY); amikacin (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ); amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (AMC) (Glaxo-SmithKline, Greenford, United Kingdom); daptomycin (Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Lexington, MA); cefoxitin, ertapenem, and IMP (Merck & Co., Inc., NJ); meropenem (Sumitomo Pharmaceuticals, Osaka, Japan); doripenem (Shionogi Pharmaceuticals, Tokyo, Japan); ciprofloxacin (CIP) and moxifloxacin (Bayer Co., West Haven, CT); levofloxacin (Daiichi Pharmaceuticals, Tokyo, Japan); gemifloxacin (LG Chem Investments, Seoul, South Korea); nemonoxacin (TaiGen Biotechnology, Co. Ltd., Taipei, Taiwan); and tigecycline (Wyeth-Ayerst, Pearl River, NY), were determined using the broth microdilution method as recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (7). Mueller-Hinton broth was the test medium for all drugs. For testing of daptomycin, the broth contained physiological levels of calcium (50 mg/liter), as recommended previously (11). The MIC interpretive criteria (susceptible/resistant) of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (≤8 and 4 μg/ml; ≥32 and 16 μg/ml), ceftriaxone (≤8 μg/ml; ≥64 μg/ml), imipenem (≤4 μg/ml; ≥16 μg/ml), ciprofloxacin (≤1 μg/ml; ≥4 μg/ml), linezolid (≤8; not applicable [NA]), sulfamethoxazole (≤32 μg/ml; ≥64 μg/ml), and amikacin (≤8 μg/ml; ≥16 μg/ml) were in accordance with those from CLSI (7). Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 28213) and Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212) were used as control strains.

RESULTS

Bacterial isolates.

During the study period, a total of 151 nonduplicated isolates were investigated. Among these isolates, N. brasiliensis (n = 60; 40%) was the most common species, followed by N. cyriacigeorgica (n = 24; 16%), N. farcinica (n = 12; 8%), N. beijingensis (n = 9), N. otitidiscaviarum (n = 8), N. nova (n = 8), N. asiatica (n = 7), N. puris (n = 6), N. flavorosea (n = 5), N. abscessus (n = 3), N. carnea (15), and one each of N. alba, N. asteroides complex, N. rhamnosiphila, N. elegans, N. jinanensis, N. takedensis, and N. transvalensis. Specimens of skin and soft tissue were the most common source of clinical Nocardia isolates, followed by respiratory tract specimens, including sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, pleural effusion, and lung biopsy specimens. In addition, some isolates were obtained from brain, blood, and lymph node biopsy specimens.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities.

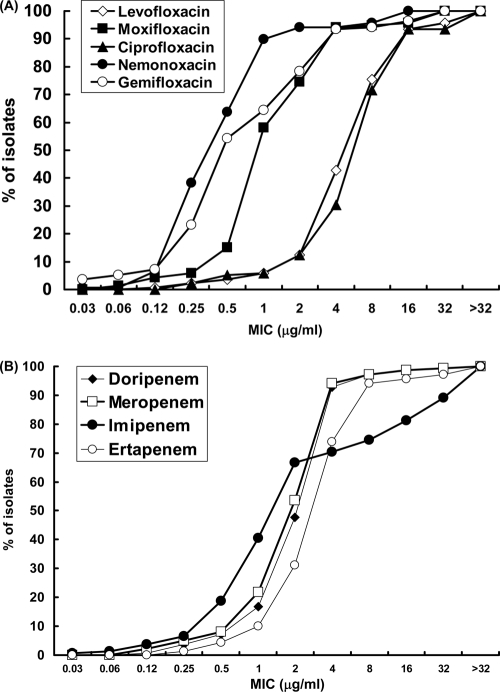

The MIC50 values, the MIC90 values, and the MIC ranges and distributions for each Nocardia species are shown in Table 1. The cumulative percentages of all 151 Nocardia isolates inhibited by each concentration of the five quinolones and four carbapenems are shown in Fig. 1A and B. For all Nocardia isolates, the MIC90 values of the tested quinolones were in the order nemonoxacin (1 μg/ml) < gemifloxacin (4 μg/ml) = moxifloxacin (4 μg/ml) < levofloxacin (16 μg/ml) = CIP (16 μg/ml), and the MIC90 values of the tested carbapenems were in the order doripenem (4 μg/ml) = meropenem (4 μg/ml) < ertapenem (8 μg/ml) < IMP (32 μg/ml). Nocardia spp. exhibited high-level resistance to vancomycin and daptomycin (MIC90s, >128 μg/ml), whereas the MIC90 of linezolid was 8 μg/ml. Among the other antimicrobial agents, amikacin and tigecycline had comparatively low MIC90 values (2 and 4 μg/ml, respectively).

Table 1.

Activities of antimicrobial agents against 151 Nocardia isolates

| Bacterium (no of isolates tested) and antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml) |

Susceptibility (%)a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | S | I | R | |

| N. brasiliensis (60) | ||||||

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 0.5–32 | 1 | 2 | 59 (98) | 1 (2) | |

| Cefoxitin | 1–>128 | 2 | 8 | |||

| Ceftriaxone | 0.5–32 | 2 | 4 | 57 (95) | 3 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Meropenem | 0.5–8 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Ertapenem | 0.25–8 | 4 | 8 | |||

| Imipenem | 0.5–>32 | 2 | >32 | 28 (47) | 3 (5) | 29 (48) |

| Doripenem | 0.5–8 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Azithromycin | 16–>128 | 32 | >128 | |||

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5–8 | 8 | 8 | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 59 (98) |

| Nemonoxacin | 0.12–1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |||

| Gemifloxacin | 0.06–2 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |||

| Levofloxacin | 1–>16 | 4 | 8 | |||

| Moxifloxacin | 0.12–2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Linezolid | 1–16 | 4 | 8 | 59 (98) | 1 (2) | |

| Vancomycin | 0.5–>128 | 128 | >128 | |||

| Daptomycin | 64–>128 | 128 | >128 | |||

| Sulfamethoxazole | 0.5–64 | 4 | 8 | 59 (98) | 1 (2) | |

| Amikacin | 0.25–4 | 1 | 2 | 60 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Tigecycline | 0.25–1 | 0.25 | 1 | |||

| N. cyriacigeorgica (24) | ||||||

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 4–16 | 16 | 16 | 9 (38) | 14 (58) | 1 (4) |

| Cefoxitin | 0.12–>16 | 4 | 16 | |||

| Ceftriaxone | 0.25–16 | 2 | 8 | 23 (96) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Meropenem | 1–4 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Ertapenem | 2–8 | 4 | 8 | |||

| Imipenem | 0.5–>4 | 1 | 2 | 24 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Doripenem | 1–8 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Azithromycin | 128–>128 | >128 | >128 | |||

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.12–128 | 16 | 64 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 24 (100) |

| Nemonoxacin | 0.25–2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Gemifloxacin | 2–8 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Levofloxacin | 8–>32 | 16 | 32 | |||

| Moxifloxacin | 2–4 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Linezolid | 2–16 | 4 | 4 | 23 (96) | 1 (4) | |

| Vancomycin | 16–>128 | 128 | >128 | |||

| Daptomycin | 128–>128 | 128 | >128 | |||

| Sulfamethoxazole | 2–16 | 4 | 4 | 24 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Amikacin | 0.5–2 | 1 | 2 | 24 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Tigecycline | 0.5–4 | 2 | 4 | |||

| N. farcinica (12) | ||||||

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 0.5–8 | 1 | 4 | 12 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cefoxitin | 0.5–>128 | 32 | >128 | |||

| Ceftriaxone | 1–>64 | 32 | 64 | 3 (25) | 5 (42) | 4 (33) |

| Meropenem | 0.5–>8 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Ertapenem | 0.5–>8 | 8 | 8 | |||

| Imipenem | 0.25–>4 | 1 | 2 | 12 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Doripenem | 0.25–>4 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Azithromycin | 128–>128 | >128 | >128 | |||

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5–128 | 8 | 16 | 6 (50) | 1 (8) | 5 (42) |

| Nemonoxacin | 0.03–1 | 0.25 | 1 | |||

| Gemifloxacin | 0.03–2 | 0.12 | 0.5 | |||

| Levofloxacin | 0.12–16 | 4 | 8 | |||

| Moxifloxacin | 0.06–8 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Linezolid | 1–4 | 4 | 4 | 12 (100) | ||

| Vancomycin | 2–>128 | 128 | >128 | |||

| Daptomycin | 64–>128 | 128 | >128 | |||

| Sulfamethoxazole | 2–64 | 8 | 32 | 11 (92) | 1 (8) | |

| Amikacin | 1–4 | 1 | 4 | 12 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Tigecycline | 0.25–8 | 1 | 8 | |||

| N. beijingensis (9) | ||||||

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 1–32 | 4 (44) | 4 (44) | 1 (11) | ||

| Cefoxitin | 1–>4 | |||||

| Ceftriaxone | 0.25–16 | 7 (78) | 2 (22) | 0 (0) | ||

| Meropenem | 0.25–2 | |||||

| Ertapenem | 2–4 | |||||

| Imipenem | 0.5–>8 | 5 (56) | 4 (44) | |||

| Doripenem | 1–2 | |||||

| Azithromycin | 64–>128 | |||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 2–128 | 0 (0) | 4 (44) | 5 (56) | ||

| Nemonoxacin | 0.5–8 | |||||

| Gemifloxacin | 0.25–16 | |||||

| Levofloxacin | 4–16 | |||||

| Moxifloxacin | 1–32 | |||||

| Linezolid | 2–4 | 9 (100) | ||||

| Vancomycin | 128–>128 | |||||

| Daptomycin | 64–>>128 | |||||

| Sulfamethoxazole | 1–4 | 9 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| Amikacin | 0.12–0.5 | 8 (89) | 1 (11) | |||

| Tigecycline | 0.12–8 | |||||

| N. otitidiscaviarum (8) | ||||||

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 32–128 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | ||

| Cefoxitin | 64–>128 | |||||

| Ceftriaxone | 16–>128 | 0 (0) | 1 (13) | 7 (87) | ||

| Meropenem | 4–>32 | |||||

| Ertapenem | 16–>32 | |||||

| Imipenem | 16–>32 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | ||

| Doripenem | 4–>32 | |||||

| Azithromycin | 0.5–>128 | |||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 2–16 | 0 (0) | 3 (37) | 5 (63) | ||

| Nemonoxacin | 0.5–2 | |||||

| Gemifloxacin | 0.5–4 | |||||

| Levofloxacin | 1–8 | |||||

| Moxifloxacin | 0.25–4 | |||||

| Linezolid | 2–4 | 8 (100) | ||||

| Vancomycin | 128–>128 | |||||

| Daptomycin | 64–128 | |||||

| Sulfamethoxazole | 4–32 | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| Amikacin | 0.5–4 | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| Tigecycline | 0.5–2 | |||||

| N. nova (8) | ||||||

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 8–64 | 1 (13) | 3 (38) | 4 (50) | ||

| Cefoxitin | 2–16 | |||||

| Ceftriaxone | 2–16 | 7 (87) | 1 (13) | 0 (0) | ||

| Meropenem | 0.12–2 | |||||

| Ertapenem | 0.5–4 | |||||

| Imipenem | 0.03–1 | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Doripenem | 0.25–2 | |||||

| Azithromycin | 0.25–>128 | |||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 4–16 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | ||

| Nemonoxacin | 0.25–1 | |||||

| Gemifloxacin | 0.5–2 | |||||

| Levofloxacin | 2–>32 | |||||

| Moxifloxacin | 0.5–4 | |||||

| Linezolid | 12 | 8 (100) | ||||

| Vancomycin | 32–>128 | |||||

| Daptomycin | 64–>128 | |||||

| Sulfamethoxazole | 4–32 | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| Amikacin | 0.12–32 | 7 (87) | 1 (13) | |||

| Tigecycline | 0.25–8 | |||||

| N. asiatica (7) | ||||||

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 16–64 | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 6 (86) | ||

| Cefoxitin | 0.5–2 | |||||

| Ceftriaxone | 0.5–1 | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Meropenem | 0.5–2 | |||||

| Ertapenem | 1–4 | |||||

| Imipenem | 0.5–1 | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Doripenem | 1–2 | |||||

| Azithromycin | >128 | |||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 64–128 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | ||

| Nemonoxacin | 16 | |||||

| Gemifloxacin | 16–32 | |||||

| Levofloxacin | >32 | |||||

| Moxifloxacin | 1–32 | |||||

| Linezolid | 1–4 | 7 (100) | ||||

| Vancomycin | 128–>128 | |||||

| Daptomycin | 128–>128 | |||||

| Sulfamethoxazole | 2–8 | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| Amikacin | 0.12–0.25 | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| Tigecycline | 0.25–1 | |||||

| N. puris (6) | ||||||

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 16 | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | ||

| Cefoxitin | 128–>128 | |||||

| Ceftriaxone | 4–>128 | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 5 (83) | ||

| Meropenem | 2–4 | |||||

| Ertapenem | 4–8 | |||||

| Imipenem | 1–2 | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Doripenem | 2–4 | |||||

| Azithromycin | 4–>128 | |||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 8 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | ||

| Nemonoxacin | 0.5 | |||||

| Gemifloxacin | 1 | |||||

| Levofloxacin | 4–8 | |||||

| Moxifloxacin | 2 | |||||

| Linezolid | 2–4 | 6 (100) | ||||

| Vancomycin | 0.5–>128 | |||||

| Daptomycin | 128–>128 | |||||

| Sulfamethoxazole | 0.5–16 | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| Amikacin | 0.12–1 | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| Tigecycline | 0.25–2 | |||||

| Other Nocardia spp. (17) | ||||||

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 1–64 | 8 | 32 | 10 (59) | 3 (18) | 4 (24) |

| Cefoxitin | 0.12–32 | 4 | 16 | |||

| Ceftriaxone | 0.25–8 | 1 | 4 | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Meropenem | 0.12–4 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Ertapenem | 0.25–16 | 2 | 8 | |||

| Imipenem | 0.12–32 | 0.5 | 2 | 16 (94) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Doripenem | 0.12–4 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Azithromycin | 1–>128 | >128 | >128 | |||

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.25–128 | 8 | 16 | 4 (24) | 1 (6) | 12 (71) |

| Nemonoxacin | 0.12–16 | 1 | 16 | |||

| Gemifloxacin | 0.06–32 | 2 | 32 | |||

| Levofloxacin | 0.25–>32 | 8 | 16 | |||

| Moxifloxacin | 0.25–32 | 4 | 32 | |||

| Linezolid | 0.5–4 | 2 | 4 | 17 (100) | ||

| Vancomycin | 0.25–>128 | 128 | >128 | |||

| Daptomycin | 0.5–>128 | 128 | >128 | |||

| Sulfamethoxazole | 4–32 | 4 | 8 | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Amikacin | 0.12–32 | 0.5 | 2 | 16 (94) | 1 (6) | |

| Tigecycline | 0.06–4 | 0.5 | 2 | |||

S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of MICs of five quinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gemifloxacin, and nemonoxacin) (A) and four carbapenems (imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem, and doripenem) (B) for the 151 Nocardia isolates.

Among all Nocardia isolates, ≤10% were resistant to amikacin, SMZ, and LZD; 17% were resistant to AMC; and 11% were resistant to CRO. In contrast, about 30% of the Nocardia isolates were nonsusceptible to IMP, particularly N. brasiliensis (53%) and N. otitidiscaviarum (100%), and most (93%) were nonsusceptible to CIP. Among the N. brasiliensis isolates, 98% were resistant to CIP and 98% were susceptible to SMZ. All N. cyriacigeorgica isolates were resistant to CIP.

For N. brasiliensis isolates, the MIC90s of the tested quinolones were in the order nemonoxacin = gemifloxacin < moxifloxacin < levofloxacin = CIP, and the MIC90s of the tested carbapenems were in the order doripenem = meropenem < ertapenem < IMP. Vancomycin and daptomycin had greater MIC90 values (>128 μg/ml), whereas the MIC90 of LZD was 8 μg/ml. Among the other antimicrobial agents, amikacin had the lowest MIC90 (2 mg/liter). More than 95% of N. brasiliensis isolates were susceptible to AMC, CRO, LZD, SMZ, and amikacin.

Comparison of the activities of different antibiotics against N. brasiliensis and N. cyriacigeorgica revealed that the MIC90s of all five of the tested quinolones, tigecycline, AMC, and cefoxitin against N. cyriacigeorgica were higher than those against N. brasiliensis. In contrast, the MIC90s of linezolid, SMZ, and IMP against N. cyriacigeorgica were lower than those against N. brasiliensis.

For the other 17 Nocardia species (Table 2), nemonoxacin had the lowest MIC90 values of the tested quinolones. Among the four tested carbapenems, IMP had the lowest MIC90s. The MIC90 of LZD was 4 μg/ml, whereas vancomycin and daptomycin had higher MIC90s (>128 μg/ml). Among the other antimicrobial agents, amikacin (2 μg/ml) and tigecycline (2 μg/ml) had the lowest MIC90 values.

Table 2.

Activities of antimicrobial agents against 17 clinical isolates of unusual Nocardia species

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml)a for: |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. flavorosea (5) | N. abscessus (3) | N. carnea (2) | N. alba (1) | N. asteroids complex (1) | N. elegans (1) | N. jinanesis (1) | N. transvalensis (1) | N. rhamnosiphila (1) | N. takedensis (1) | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 4–16 (60) | 1–32 (67) | 32 (0) | 2 (S) | 64 (R) | 16 (R) | 8 (S) | 8 (S) | 8 (S) | 1 (S) |

| Cefoxitin | 0.12–16 | 1–16 | 1–16 | 2 | 32 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 1 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.25–8 (100) | 0.5–2 (100) | 2–4 (100) | 2 (S) | 8 (S) | 4 (S) | 2 (S) | 4 (S) | 1 (S) | 2 (S) |

| Meropenem | 1–4 | 1–4 | 1 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.12 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Ertapenem | 2–8 | 1–8 | 0.5–2 | 1 | 2 | 0.25 | 4 | 16 | 2 | 2 |

| Imipenem | 0.5–2 (100) | 0.25–1 (100) | 0.25–0.5 (100) | 1 (S) | 1 (S) | 0.12 (S) | 0.5 (S) | 32 (R) | 0.5 (S) | 1 (S) |

| Doripenem | 1–4 | 0.25–4 | 1 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.12 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Azithromycin | >128 | 32–>128 | 16–>128 | 16 | 128 | 1 | 128 | 32 | >128 | 32 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 4–16 (0) | 4–128 (0) | 0.25 (100) | 2 (R) | 16 (R) | 16 (R) | 8 (R) | 1 (S) | 1 (S) | 4 |

| Nemonoxacin | 0.25–1 | 0.5–16 | 0.12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 |

| Gemifloxacin | 2–4 | 0.5–32 | 0.03–0.06 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.5 |

| Levofloxacin | 8–16 | 2–>32 | 0.25–0.5 | 8 | 4 | 16 | 8 | 0.5 | 2 | 4 |

| Moxifloxacin | 2–4 | 2–32 | 0.25 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Linezolid | 2–4 (100) | 0.5–2 (100) | 0.5–2 (100) | 2 (S) | 4 (S) | 2 (S) | 4 (S) | 1 (S) | 2 (S) | 4 (S) |

| Vancomycin | 16–>128 | 0.25–128 | 128 | 0.25 | 16 | 32 | 128 | >128 | 128 | 128 |

| Daptomycin | 128–>128 | 0.5–128 | 128–>128 | 1 | 128 | >128 | 128 | >128 | 128 | 128 |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 4–8 (100) | 8 (100) | 4–8 (100) | 32 (S) | 4 (S) | 8 (S) | 4 (S) | 32 (S) | 4 (S) | 4 (S) |

| Amikacin | 0.5–4 (100) | 0.12–4 (100) | 0.12–0.25 (100) | 0.25 (S) | 0.5 (S) | 0.25 (S) | 0.5 (S) | 32 (R) | 0.25 (S) | 1 (S) |

| Tigecycline | 0.5–2 | 0.12–2 | 0.5–1 | 0.06 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

The MIC range is shown, with the percentage of susceptible isolates or susceptibility category (S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant) in parentheses. The number of isolates for each species is shown in parentheses.

The resistance profiles of various clinical isolates are shown in Table 3. Concomitant CIP-IMP resistance and AMC-CIP resistance were the most common profiles. All of the clinical isolates of N. beijingensis, N. nova, and N. puris were resistant to at least one antimicrobial agent. More than half of N. brasiliensis and N. cyriacigeorgica isolates were resistant to more than two agents. For N. otitidiscaviarum, all eight of the isolates were resistant to AMC, ceftriaxone, CIP, and imipenem.

Table 3.

Multiple-resistance profiles of the clinical isolates of Nocardia spp.

| Resistance profilea | Nocardia sp.b |

|---|---|

| AN-IMI | N. transvalensis (1/100) |

| AMC-CRO | N. brasiliensis (1/2) |

| AMC-CIP | N. cyriacigeorgica (13/54), N. beijingensis (5/56), N. nova (7/87), N. asiatica (7/100), N. flavorosea (2/40), N. puris (1/100), N. abscessus (1/100), N. asteroides complex (1/100), N. elegans (1/100) |

| CRO-CIP | N. farcinica (4/33) |

| CIP-IMP | N. brasiliensis (33/55), N. beijingensis (3/33) |

| AMC-CRO-CIP | N. puris (5/83), N. cyriacigeorgica (1/5) |

| AMC-CIP-LZD | N. cyriacigeorgica (1/4) |

| AN-CRO-CIP | N. nova (1/13) |

| CRO-CIP-IMP | N. brasiliensis (1/2) |

| CRO-CIP-SMZ | N. farcinica (1/8) |

| AN-CRO-CIP-IMI | N. beijingensis (1/11) |

| AMC-CRO-CIP-IMP | N. otitidiscaviarum (8/100) |

| CRO-CIP-SMZ-LZD | N. brasiliensis (1/2) |

Including intermediate and resistant. AN, amikacin.

The number/percentage of isolates in each species are shown in parentheses.

DISCUSSION

This nationwide study in Taiwan investigated the antibiotic susceptibilities of various Nocardia species based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis of the isolates. Our findings show that the two most common nocardial pathogens in Taiwan are N. brasiliensis (60/151; 40%) and N. cyriacigeorgica (24/151; 16%). In contrast, N. nova complex organisms are the most common isolates in the United States (211/765; 28%) and Canada (109/325; 34%) (22, 23), and N. cyriacigeorgica (12/37; 32%) is the most common pathogen in Spain (15). In addition, we demonstrated that Nocardia species vary in their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Overall, our findings suggest that accurate identification is essential to understanding the epidemiological distribution of different species and predicting their antimicrobial susceptibilities.

More than 80% of Nocardia isolates were resistant to CIP, and the overall MIC50 and MIC90 values were 8 μg/ml and 16 μg/ml, respectively. These findings are consistent with those reported in previous studies conducted in the United States and South Africa (14, 23). In contrast, nemonoxacin (TG-873870), a novel quinolone, has much lower MIC values than the four classic quinolones CIP, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and gemifloxacin. Furthermore, MIC determinations revealed that the MIC90s of nemonoxacin and gemifloxacin were the lowest among the five tested quinolones against most of the Nocardia species determined in this study.

Nemonoxacin, currently available only in an oral formulation, is rapidly absorbed following oral administration. The free maximum concentration of drug in serum (Cmax) is 5.7 μg/ml, and the mean 24-h free area under the concentration-time curve (fAUC0–24) is 46.0 μg · h/ml for a single 750-mg dose (6). The MIC breakpoint of nemonoxacin has not been established. For treatment of infections due to Gram-positive cocci, a fAUC0–24/MIC ratio of >30 is generally accepted to predict clinical success and microbiological success (6). Accordingly, nemonoxacin displayed good pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics at the 750-mg dose with a fAUC0–24/MIC90 ratio of 92 μg · h/ml for N. brasiliensis and 46 μg · h/ml for N. farcinica and also had favorable results (fAUC0–24/MIC ≥ 46 μg · h/ml) for the majority (>90%) of N. puris and N. nova isolates. This agent showed unfavorable results for N. cyriacigeorgica, N. beijingensis, and other Nocardia spp. Although nemonoxacin showed promising activity against most Nocardia spp. in this study, further clinical evaluation is needed to demonstrate the clinical role of nemonoxacin in the management of nocardiosis.

Previous in vitro studies have shown that LZD is quite active against multiple Nocardia isolates (4, 14, 23). In this study, we found that, with the exception of N. brasiliensis and N. cyriacigeorgica, all of the isolates were susceptible to LZD. These findings suggest that LZD is a good alternative to sulfa-based antibiotics for the treatment of nocardiosis; however, clinicians still need to be aware of the rare occurrence of in vitro non-LZD-susceptible Nocardia isolates.

Few studies have provided data on the in vitro activity of daptomycin against unusual clinically relevant Gram-positive microbes, such as Nocardia spp. (9). In this study, daptomycin showed poor in vitro activity against each Nocardia species. In fact, the MIC90s (≥128 μg/ml) were similar to those of vancomycin. Although the relationship between in vitro susceptibilities and in vivo response based on clinical studies is unknown, our findings suggest that the clinical role of daptomycin for treating nocardiosis is as limited as that of vancomycin.

Knowledge about the activities of tigecycline against different Nocardia species is limited (5). In the present study, tigecycline was the most effective against N. brasiliensis and N. puris. Overall, tigecycline MIC values were ≤8 μg/ml against all of the tested isolates. These results, as well as those reported in a previous study (5), support the potential clinical application of tigecycline for the treatment of nocardiosis. To the best of our knowledge, only one other study has tested the activity of doripenem against Nocardia sp. isolates (11). In our study, different Nocardia spp. exhibited different patterns of susceptibility to carbapenems, and the MICs of doripenem against different Nocardia species were comparable to those of meropenem. Overall, the rate of IMP-resistant Nocardia isolates was 29%, and those for N. otitidiscaviarum (100%) and N. brasiliensis (48%) were especially high. In general, the activities of the four tested carbapenems against Nocardia species ranked in the order meropenem and doripenem > IMP and ertapenem. These findings indicate that doripenem may be a better choice of carbapenems than IMP to treat nocardial infections, although all of the carbapenems show poor activity against N. otitidiscaviarum isolates.

We also studied the in vitro activity of cephalosporins (CRO and cefoxitin) against isolates of Nocardia. Overall, the rate of CRO-resistant Nocardia isolates was 11%; however, these agents showed poor activity (MIC ≥ 64 μg/ml) against N. otitidiscaviarum, N. farcinica, and N. puris. The activities of traditional antimicrobials, including SMZ, AMC, and amikacin, were also assayed in the present work. SMZ showed good in vitro activity, and only three isolates were resistant to SMZ. However, in a retrospective evaluation of the antibiotic resistance patterns of 765 Nocardia isolates in the United States, 61% were resistant to SMZ and 42% were resistant to TMP-SMZ (23). In another study of 37 strains of Nocardia isolates in Spain, only 10.8% were resistant to TMP-SMZ (15). The differences may be due to geographical variation and species distribution. In Taiwan, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is still effective for the treatment of nocardiosis. In addition, with the exception of one isolate of N. nova, which was resistant to amikacin, all Nocardia isolates were uniformly susceptible to amikacin (MICs ≤ 8 μg/ml). This finding differs from that reported by Uhde et al., who reported that only 5% of 765 Nocardia isolates in the United States were susceptible to amikacin (23). In contrast, AMC showed various activities against different Nocardia species, and more than 80% of N. otitidiscaviarum, N. puris, and N. asiatica isolates were resistant to AMC.

The sulfonamide antibiotic combination TMP-SMZ continues to be the drug of choice for nocardiosis (3, 12, 13, 15); however, treatment failure has been noted when it is used alone, especially in disseminated and central nervous system nocardiosis. Thus, various combination therapy regimens, including IMP, amikacin, minocycline, LZD, and cephalosporins, have been recommended for the management of serious Nocardia infections (2, 13, 18, 21). In this study, we noted that more than half of N. brasiliensis and N. cyriacigeorgica isolates and all of the N. beijingensis, N. otitidiscaviarum, N. nova, and N. puris isolates were resistant to at least one antimicrobial agent. The most notable was N. otitidiscaviarum, because all eight isolates were nonsusceptible to a combination of AMC, CRO, IMP, and CIP. Studies on the synergistic effect in vivo have reported conflicting results (13, 16); therefore, further clinical studies are needed to evaluate the in vivo and in vitro activities of combination therapy.

In conclusion, the results of this in vitro study suggest that TMP-SMZ has good activity against clinical isolates of Nocardia species in Taiwan. We also found that nemonoxacin, linezolid, and tigecycline show promise as alternatives to sulfa-based antibiotics for the treatment of nocardiosis. In addition, it is important to determine the species of Nocardia, because different species and isolates vary in their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 February 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Benbow E. P., Jr., Smith D. T., Grimson K. S. 1944. Sulfonamide therapy in actinomycosis: two cases caused by aerobic partially acid-fast actinomyces. Am. Rev. Tuberc. 49:395–407 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Betriu C. 2006. Nocardia infections. Enferm. Infect. Microbiol. Clin. 11:709–714 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown-Elliott B. A., Brown J. M., Conville P. S., Wallace R. J., Jr 2006. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19:259–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown-Elliott B. A., et al. 2001. In vitro activities of linezolid against multiple Nocardia species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1295–1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cercenado E., et al. 2007. In vitro activities of tigecycline and eight other antimicrobials against different Nocardia species identified by molecular methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1102–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen Y. H., Liu C. Y., Lu J. J., King C. H., Hsueh P. R. 2009. In vitro activity of nemonoxacin (TG-873870), a novel non-fluorinated quinolone, against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, enterococci and Streptococcus pneumoniae with various resistance phenotypes in Taiwan. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:1226–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. CLSI/NCCLS. 2003. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes. Approved standard M24-A. CLSI/NCCLS, Wayne, PA: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Glover R. P., Herrell W. E., Heilman F. R., Pfuetze K. H. 1948. Nocardia asteroides infection simulating pulmonary tuberculosis. JAMA 136:172–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huang Y. T., Liao C. H., Teng L. J., Hsueh P. R. 2007. Daptomycin susceptibility of unusual gram-positive bacteria: comparison of results obtained by the Etest and the broth microdilution method. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1570–1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lai C. C., et al. 2011. Antimicrobial-resistant Nocardia Isolates, Taiwan, 1998–2009. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:833–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lai C. C., et al. 2009. Comparative in vitro activities of nemonoxacin, doripenem, tigecycline and 16 other antimicrobials against Nocardia brasiliensis, Nocardia asteroides and unusual Nocardia species. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lederman E. R., Crum N. F. 2004. A case series and focused review of nocardiosis: clinical and microbiologic aspects. Medicine (Baltimore) 40:300–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lerner P. I. 1996. Nocardiosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 22:891–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lowman W., Aithma N. 2010. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing and profiling of Nocardia species and other aerobic Actinomycetes from South Africa: comparative evaluation of broth microdilution versus the Etest. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:4534–4540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Minero M. V., et al. 2009. Nocardiosis at the turn of the century. Medicine (Baltimore) 88:250–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moylett E. H., et al. 2003. Clinical experience with linezolid for the treatment of nocardial infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:313–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Muñoz J., et al. 2007. Clinical and microbiological features of nocardiosis, 1997–2003. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:545–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saubolle M. A., Sussland D. 2003. Nocardiosis: review of clinical and laboratory experience. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4497–4501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tan C. K., et al. 2009. Comparative in vitro activities of the new quinolone nemonoxacin (TG-873870), gemifloxacin and other quinolones against clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:428–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tan C. K., et al. 2010. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of nocardiosis including those caused by emerging Nocardia species in Taiwan, 1998–2008. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:966–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Threlkeld S. C., Hooper D. C. 1997. Update on management of patients with Nocardia infection. Curr. Clin. Top. Infect. Dis. 17:1–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tremblay J., Thibert L., Alarie I., Valiquette L., Pépin J. 15 July 2010. Nocardiosis in Quebec, Canada, 1988–2008. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03306.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Uhde K. B., et al. 2010. Antimicrobial-resistant Nocardia isolates, United States, 1995–2004. Clin. Infect. Dis. 51:1445–1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wallace R. J., Jr., et al. 1982. Use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for treatment of infections due to Nocardia. Rev. Infect. Dis. 4:315–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Welsh O., Vera-Cabrera L., Salinas-Carmona M. C. 2007. Mycetoma. Clin. Dermatol. 25:195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]