Abstract

Disk diffusion testing has recently been standardized by the CLSI, and susceptibility breakpoints have been established for several antifungal compounds. For caspofungin, 5-μg disks are approved, and for micafungin, 10-μg disks are under evaluation. We evaluated the performances of caspofungin and micafungin disk testing using a panel of Candida isolates with and without known FKS echinocandin resistance mechanisms. Disk diffusion and microdilution assays were performed strictly according to CLSI documents M44-A2 and M27-A3. Eighty-nine clinical Candida isolates were included: Candida albicans (20 isolates/10 mutants), C. glabrata (19 isolates/10 mutants), C. dubliniensis (2 isolates/1 mutant), C. krusei (16 isolates/3 mutants), C. parapsilosis (14 isolates/0 mutants), and C. tropicalis (18 isolates/4 mutants). Quality control strains were C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 and C. krusei ATCC 6258. The correlations between zone diameters and MIC results were good for both compounds, with identical susceptibility classifications for 93.3% of the isolates by applying the current CLSI breakpoints. However, the numbers of fks hot spot mutant isolates misclassified as being susceptible (S) (very major errors [VMEs]) were high (61% for caspofungin [S, ≥11 mm] and 93% for micafungin [S, ≥14 mm]). Changing the disk diffusion breakpoint to S at ≥22 mm significantly improved the discrimination. For caspofungin, 1 VME was detected (a C. tropicalis isolate with an F76S substitution) (3.5%), and for micafungin, 10 VMEs were detected, the majority of which were for C. glabrata (8/10). The broadest separation between zone diameter ranges for wild-type (WT) and mutant isolates was seen for caspofungin (6 to 12 mm versus −4 to 7 mm). In conclusion, caspofungin disk diffusion testing with a modified breakpoint led to excellent separation between WT and mutant isolates for all Candida species.

INTRODUCTION

Disk diffusion susceptibility testing is widely used for antibacterial compounds in routine clinical microbiology laboratories, and thus, this concept is also attractive for antifungal susceptibility testing. The CLSI has approved a disk diffusion methodology for the testing of several antifungals (document M44-A2), including caspofungin. Disk diffusion breakpoints have been established based upon the best possible correlation to MIC results and susceptibility classification obtained by CLSI microdilution method M27-A3 (4, 6). The current CLSI microdilution breakpoints for echinocandins (susceptible [S], ≤2 μg/ml; nonsusceptible [NS], >2 μg/ml) were established before resistant mutants emerged and were based upon MIC relationships to clinical outcome, MIC distributions, and pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters (5, 13). However, during the last few years isolates with mutations in the fks hot spot regions have emerged and have been associated with clinical failure. Hence, sensitive susceptibility tests able to discriminate between these isolates and wild-type (WT) isolates have become increasingly important. Several publications have described the failure of the initial CLSI breakpoints to correctly identify resistant mutants (1–3, 7, 8, 10–12), and thus, in the summer of 2010 the CLSI approved revised echinocandin breakpoints (http://www.clsi.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Committees/Microbiology/SCAntifungalSusceptibilityTesting/January2010AntifungalSusceptibilityMeetingPresentations/2a_CMRClinicalBreakpoints_EchinocandinsAndCandida_part2.pdf).

In this study, we evaluate and compare the performances of CLSI disk diffusion susceptibility tests for caspofungin and micafungin using a well-characterized panel of susceptible WT isolates and fks hot spot mutant isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates.

A well-characterized set of WT and fks hot spot mutant isolates was used (2), including 89 clinical isolates and 2 quality control reference strains (C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 and C. krusei ATCC 6258). Clinical isolates included 10 FKS WT and 10 fks hot spot mutant C. albicans isolates (Fks1p with F641S [n = 2], S645P [n = 3], S645F-plus-R1361R/H, S645Y, SD645F, D648Y, and P649H mutations), 9 FKS WT and 10 fks hot spot mutant C. glabrata isolates (Fks1p, with F625S, S629P, D632G, F659V, S663P, D666G, D666E, and P667T mutations; Fks2p with F659S and S663F mutations), 1 FKS WT and 1 fks hot spot mutant C. dubliniensis isolate (Fks1p with a S645P mutation), 13 FKS hot spot WT and 3 fks hot spot mutant C. krusei isolates (Fks1p with R1361G, F655F/C, and L658W-plus-L701M mutations), 14 FKS WT C. parapsilosis isolates, and 14 FKS hot spot WT and 4 fks hot spot mutant C. tropicalis isolates (Fks1p with S80P [n = 3] and F76S mutations). Three isolates were found to harbor mutations outside the resistance hot spots and were regarded as WT concerning echinocandin susceptibility because of their normal kinetic inhibition properties. Thus, a total of 28 isolates with characteristic echinocandin resistance mutations in the hot spot regions were included. These isolates were clinical isolates referred to the authors' laboratories (D.S.P. or M.C.A.), with the exception of one clinical C. krusei isolate that was provided by F. Dromer. All isolates were coded, and tests were performed blinded for susceptibility patterns.

Compounds.

Pure substances provided by the manufacturers were one lot of caspofungin by Merck (TEK0010) and one lot of micafungin by Astellas (122320KA). Stock solutions for microdilution testing were prepared in water, taking into account the potencies of the powders.

Disk diffusion testing.

Disk diffusion testing was performed strictly according to CLSI standard M44-A2 (6), using Mueller-Hinton agar plus 2% glucose and 0.5 μg/ml methylene blue dye (SSI Diagnostica, Hillerød, Denmark). Caspofungin-impregnated paper disks containing 5 μg of caspofungin (lot no. 372738; Oxoid) were provided by Merck. Micafungin-impregnated paper disks containing 10 μg micafungin (lot no. 9268810; Becton Dickinson) were provided by Astellas. Zone diameters were read by using a digital ruler, and values were rounded to closest millimeter. Minor trailing growth in the inhibition zones was ignored. C. krusei ATCC 6258 and C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 were used as quality control strains, and results were within the recommended ranges (Table 1).

Table 1.

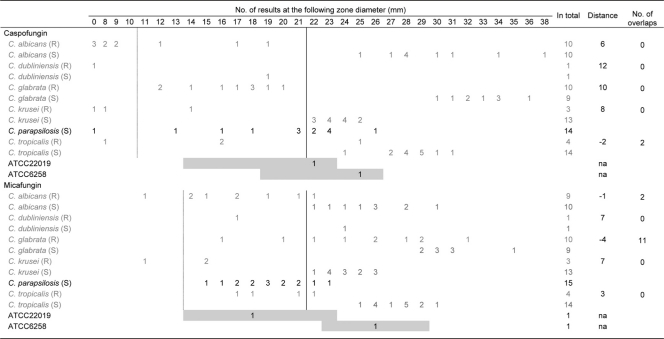

Caspofungin and micafungin disk diffusion results for WT isolates and fks hot spot mutant isolatesa

Distance indicates the distance between the range for the susceptible WT population and the range for the fks hot spot mutant population for each species. A negative value indicates overlap between the two populations. The number of overlaps is calculated as the numbers of fks hot spot and WT isolates for which inhibition zone diameters were overlapping for each species. The dotted line indicates CLSI disk diffusion breakpoints (S, ≥x mm) for caspofungin according to CLSI document M44-A2 and for micafungin as proposed at the CLSI meeting in January 2010 based upon correlation to susceptibility classification using 2 μg/ml as the breakpoint for susceptibility. The solid line indicates the suggested disk diffusion breakpoint (S, ≥x mm) for species other than C. parapsilosis based upon results obtained in the current study. Gray boxes indicate recommended quality control zone diameter (mm) ranges. NA, not applicable.

CLSI microdilution.

CLSI microdilution was performed strictly according to CLSI standard M27-A3 (5). Plates were stored at −86°C for a maximum of 15 days before use. Microtiter plates were read visually, and the MIC was determined using prominent inhibition (corresponding to 50%) as an endpoint. Geometric mean values of triplicate determinations were calculated, and the values in-between the log2 scale were adjusted to the upper closest log2 value for comparison. C. krusei ATCC 6258 and C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 were used as quality control strains throughout all experiments.

FKS gene sequence analysis.

FKS gene sequence analysis was performed for all isolates as described previously (2).

Evaluation of test performance.

For each of the drug-bug combinations, the following parameters were used to evaluate and compare the test performance: distance between zone diameter ranges (mm) for fks hot spot mutant isolates and WT isolates, where negative values indicate the overlap between these diameter ranges; number of overlaps, calculated as the number of fks hot spot and WT isolates for which inhibition zone diameters were overlapping; and VMEs (very major errors), or the number of fks hot spot mutant isolates for which the zone diameters fell within the zone diameter range of the corresponding WT population. Finally, the current and revised or proposed echinocandin breakpoints for susceptibility were applied. Current breakpoints are as follows: S at an MIC of ≤2 μg/ml for both echinocandins for MIC determinations and caspofungin S at zone diameter of ≥11 mm and micafungin S at zone diameter of ≥14 mm by disk diffusion (proposed at the CLSI 2010 meeting in San Diego, CA) (5, 6). The revised species-specific breakpoint for C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. krusei, and C. tropicalis was S at ≤0.25 μg/ml, except for micafungin and C. glabrata (S, ≤0.06 μg/ml). The revised disk diffusion breakpoint for these species and caspofungin is S at ≥18 mm. The proposed revised micafungin disk diffusion breakpoints for susceptibility are S at ≥26 mm for C. albicans and C. tropicalis, S at ≥30 mm for C. glabrata, and S at ≥24 mm forC. krusei (Table 2) (http://www.clsi.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Committees/Microbiology/SCAntifungalSusceptibilityTesting/January2010AntifungalSusceptibilityMeetingPresentations/2a_CMRClinicalBreakpoints_EchinocandinsAndCandida_part2.pdf).

Table 2.

Numbers of VMEs obtained by disk diffusion testing according to current, revised, and alternative breakpoints for susceptibilitya

| Breakpoint (diam [mm]) | No. of VMEs/total no. of isolates tested |

Total % of VMEs (28 mutants) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | C. dubliniensis | C. glabrata | C. krusei | C. tropicalis | ||

| Caspofungin | ||||||

| Current (≥11) | 3/10 | 0/1 | 10/10 | 1/3 | 3/4 | 61 |

| Revised (≥18) | 1/10 | 0/1 | 5/10 | 0/3 | 1/4 | 25 |

| Alternative (≥22) | 0/10 | 0/1 | 0/10 | 0/3 | 1/4 | 4 |

| Micafungin | ||||||

| Proposed (≥14) | 5/9 | 1/1 | 10/10 | 2/3 | 4/4 | 93 |

| Revised (Sp Speca) | 0/9 | 0/1 | 1/10 | 0/3 | 0/4 | 4 |

| Alternative (≥22) | 1/9 | 0/1 | 8/10 | 0/3 | 1/4 | 36 (12 excluding C. glabrata) |

Sp Spec, specific species. Revised micafungin breakpoints for susceptibility for C. albicans and C. tropicalis are as follows: S at ≥26 mm, S at ≥30 mm for C. glabrata, and S at ≥24 mm for C. krusei (M. A. Pfaller et al., unpublished data).

Linear regression analysis.

Linear regression analysis was done for CLSI MICs (log2 transformed) versus disk diffusion diameters using the Prism program, version 5.03.

RESULTS

Overall correlation between CLSI disk diffusion and microdilution results.

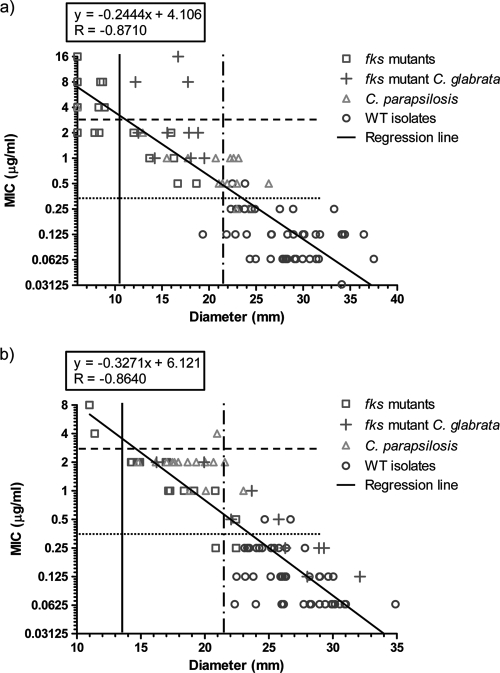

A good correlation between disk zone diameters and CLSI MICs were found for both compounds, leading to a high level of agreement between the susceptibility classifications obtained by the two methods using current CLSI breakpoints (Fig. 1). Thus, using current breakpoints for caspofungin, only three isolates (all C. glabrata fks hot spot mutants) were classified as being susceptible using disk diffusion but not microdilution, and three other fks mutant isolates were classified as being resistant using disk diffusion but susceptible by microdilution (Fig. 1a). Similarly, for micafungin, correlation was excellent, with a single C. parapsilosis isolate being classified as resistant by microdilution but susceptible by disk diffusion (Fig. 1b). However, a substantial proportion of the fks hot spot mutant isolates were misclassified as being susceptible with both methods and with both echinocandins using the currently approved breakpoints. The application of the proposed revised breakpoint of ≤0.25 μg/ml for susceptibility yielded a much better separation between WT and fks hot spot mutant isolates, except for C. glabrata and micafungin. A high overall agreement with the classification obtained using the revised microdilution breakpoint was obtained if ≥22 mm was used for susceptibility for disk testing (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CLSI MIC endpoints versus disk diffusion zone diameters for 5-μg caspofungin disks (a) and 10-μg micafungin disks (b). Wild-type isolates are indicated as triangles for C. parapsilosis and as circles for other species. Hot spot mutant isolates are indicated as crosses for C. glabrata and as open squares for other species. Dashed horizontal lines indicate initially approved CLSI microdilution breakpoints for susceptibility; dotted horizontal lines indicate revised CLSI microdilution breakpoints for susceptibility; vertical unbroken lines indicate current CLSI disk diffusion breakpoints for caspofungin and proposed micafungin breakpoints derived from the initially approved microdilution breakpoint, respectively; and dashed-dotted vertical lines indicate the best split between WT and hot spot mutant isolates for disk diffusion testing in this study. No inhibition zone is indicated as a zone diameter of 6 mm (size of the disk). The regression line is based upon the log2 MIC value and the zone diameter. Breakpoint lines are drawn at the separation between “S” and “non-S” values in order not to intercept data points.

Separation of WT and fks hot spot mutant isolates by species.

The disk diffusion results are shown by individual species and FKS genotype in Table 1. For caspofungin, excellent separation between WT and fks hot spot mutant isolates was seen for all isolates except for one C. tropicalis isolate (zone diameter of 24 mm) harboring an F76S mutation and with a caspofungin MIC of 0.25 μg/ml. Thus, the other populations were separated by 6 to 12 mm. By applying the currently approved CLSI disk diffusion breakpoint, 61% of fks hot spot mutant isolates were misclassified as being susceptible (Table 2). Using the revised breakpoint, this was the case for 25% of the isolates with fks hot spot mutations, the majority of which were C. glabrata isolates; however, if a breakpoint of ≥22 mm was used as the susceptibility breakpoint for species other than C. parapsilosis, only the C. tropicalis isolate mentioned above was misclassified as being susceptible, and one susceptible WT isolate (C. dubliniensis) was misclassified as being resistant (Table 2).

For micafungin, the separation between WT and fks hot spot mutant isolate populations was less optimal (Table 1). The distance between the two populations ranged from −4 to 7 mm, and 13 isolates were involved in overlaps between the two populations. While a good separation was seen for C. krusei and C. tropicalis WT and fks hot spot mutant isolate populations, a minor overlap was seen for C. albicans (involving 1 fks hot spot mutant isolate with a P649H mutation and a micafungin CLSI MIC of 0.5 μg/ml) and a considerable overlap was seen for C. glabrata, involving 3 fks hot spot mutant isolates (one with a D666E mutation and an MIC of 0.125 μg/ml, one with a P667T mutation and an MIC of 0.25 μg/ml, and one with a D632G mutation and an MIC of 0.125 μg/ml). By applying the suggested CLSI breakpoint (S, ≥14 mm) translated from the microdilution breakpoint of ≤2 μg/ml, all but two isolates with fks hot spot mutations were misclassified as being susceptible (25/27; 93%) (Table 2). The application of the revised species-specific breakpoints resulted in a significant reduction of VMEs, as only one C. glabrata mutant (with a D632G mutation and an MIC of 0.125 μg/ml) was misclassified. However, these breakpoints bisected the WT isolates for C. albicans and C. dubliniensis (5/11 isolates misclassified as being not susceptible), C. glabrata (2/9 misclassified as being not susceptible), C. krusei (5/13 misclassified as being not susceptible), and C. tropicalis (1/14 misclassified as being not susceptible) (in total, 13/47 isolates [28%]). However, if using the highest value not categorizing any WT isolates as being not susceptible for the susceptibility breakpoint for C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. krusei, and C. tropicalis isolates (S, ≥22 mm), the number of VMEs was reduced from 15/17 (88%) to 2/17 (12%) (one C. albicans isolate with a P649H mutation and an MIC of 0.5 μg/ml and one C. tropicalis isolate with an F76S mutation and a micafungin MIC of 0.25 μg/ml).

The zone diameters for both compounds and C. parapsilosis isolates overlapped with the fks hot spot mutant isolate population ranges for the other species. Particularly for caspofungin, variation in zone diameter was considerable (no zone to 26 mm; median, 21 mm).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated a good correlation between the CLSI microdilution MICs and disk diffusion zone diameters for caspofungin and micafungin, consistent with previously reported findings for caspofungin (4). This suggests that this method may be a useful alternative to the more-labor- and expertise-requiring microdilution reference methodology. However, if applying the breakpoints derived from the currently used CLSI microdilution breakpoints, fks hot spot mutant isolates will be misclassified in 61% of the cases for caspofungin and in as many as 93% of the cases for micafungin. Although these figures were reduced when the zone diameters were interpreted according to the revised breakpoints, 25% VMEs were still observed for caspofungin, and 4% VMEs and 28% major errors (WT isolates being classified as nonsusceptible) were still observed for micafungin.

For caspofungin disk diffusion testing, all but one such very major errors could be avoided by using a breakpoint of ≥22 mm as susceptible for species other than C. parapsilosis. Furthermore, the susceptibility classification obtained by applying this breakpoint for the isolates in this study was in excellent agreement with the classification obtained if using the recently approved revised microdilution breakpoint for susceptibility of an MIC of ≤0.25 mg/ml (http://www.clsi.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Committees/Microbiology/SCAntifungalSusceptibilityTesting/January2010AntifungalSusceptibilityMeetingPresentations/2a_CMRClinicalBreakpoints_EchinocandinsAndCandida_part2.pdf). Future studies are needed to determine if a breakpoint of ≥22 mm is too restrictive in the sense that it will lead to too many major errors. However, if used as a screening test to identify isolates for subsequent MIC determinations, a restrictive breakpoint might be preferable.

For micafungin the separation between WT and fks mutant isolates was less impressive, and for C. glabrata the two populations overlapped significantly. This phenomenon has similarly been seen with EUCAST as well as CLSI microdilution testing guidelines (2) and thus appears to be drug-bug related rather than dependent on the choice of the in vitro susceptibility test format. It remains to be understood if micafungin has a better efficacy against C. glabrata fks hot spot mutants with MICs and zone diameters within the WT range. However, with the goal of distinguishing between WT and fks hot spot mutant isolates, micafungin disk testing appears to be less optimal due to close or overlapping susceptible and mutant populations and the need for individual breakpoints for not only C. parapsilosis but also C. glabrata.

Susceptibility testing by disk diffusion as well as microdilution methods indicated that the position of the mutation affected the loss of susceptibility. For example, mutations leading to amino acid substitutions at position S645 (equivalent to position S80 in C. tropicalis) were consistently associated with a more pronounced MIC elevation and a more pronounced zone diameter reduction than those of several of the other mutations. This is in agreement with the previously reported differentiated changes in the drug susceptibility of the glucan synthase enzyme (9). Whether this genotypic difference translates into a more moderate in vivo resistance and better clinical efficacy than those of the highly resistant genotypes remains to be explored.

In conclusion, disk diffusion testing for Candida species and caspofungin appears to be a promising tool for differentiating echinocandin-susceptible WT from fks hot spot mutant isolates. Nevertheless, while susceptibility classification is improved by the application of recently revised breakpoints, further evaluation and refinement are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Birgit Brandt for excellent technical assistance. We thank Francoise Dromer, Unité de Mycologie Moléculaire, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France, for providing one of the candin fks hot spot mutant C. krusei isolates. We thank Astellas for providing micafungin pure substance and disks and Merck for providing caspofungin pure substance and disks.

The study was supported by NIH grant AI069397 to D.S.P.

M.C.A. has been a consultant for Astellas, Merck, Pfizer, and SpePharm; has been an invited speaker for Astellas, Cephalon, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Schering-Plough, and Swedish Orphan; and has received research funding for this particular study from Astellas, Merck, and Pfizer. D.S.P. is shareholder in Merck; has acted as a consultant for Merck, Pfizer, and Astellas; is advisory board member for Merck, Pfizer, Astellas, and Myconostica; has patent application 07763-O69WO1; has received research funding, although not for this particular study, from Merck, Pfizer, Astellas, and Myconostica; and has been an invited speaker for Merck, Pfizer, Astellas, and Myconostica. M.P. has been an invited speaker for Astellas, Pfizer, Merck, and Schering; has received research grants from Astellas, AB Biodisk, BioMerieux, Pfizer, Schering, Merck, Esai, and MethylGene; and is advisory board member for Astellas, Pfizer, Merck, Schering, Esai, MethylGene, and Becton Dickinson. S.P. has no conflicts to declare. S.B. has received research grants from Achaogen, Aggenix, Alda, Astellas, Apex, Ascent, AstraZeneca, AvidBiotics, Bausch & Lomb, Bayer, BioMerieux, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Calixa, Cerexa, Cubist, Eisai, Enturia, Essential Therapeutics, Forest, Fujisawa, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Intervet, Janssen Ortho-McNeil, Johnson & Johnson, Kosan, Leo, Magainin, Mediflex, Merck, Mutabilis, Novexel, Oscient, Otsuka, Paratek, Peninsula, Pfizer, Protez, Replidyne, Schering, Schering-Plough, Theravance, Vertex, and Wyeth and has acted as advisor/consultant for Sanofi-Aventis and Gilead Scientific.

The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the pharmaceutical companies.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 February 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arendrup M. C., et al. 2009. Breakthrough Aspergillus fumigatus and Candida albicans double infection during caspofungin treatment: laboratory characteristics and implication for susceptibility testing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1185–1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arendrup M. C., et al. 2010. Echinocandin susceptibility testing of Candida species: comparison of EUCAST EDef 7.1, CLSI M27-A3, Etest, disk diffusion, and agar dilution methods with RPMI and IsoSensitest media. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:426–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baixench M. T., et al. 2007. Acquired resistance to echinocandins in Candida albicans: case report and review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59:1076–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown S. D., Traczewski M. M. 2008. Caspofungin disk diffusion breakpoints and quality control. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:1927–1929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved standard, 3rd ed., CLSI document M27-A3 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2009. Method for antifungal disk diffusion susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved guideline, 2nd ed., M44-A2 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 7. Desnos-Ollivier M., et al. 2008. Mutations in the fks1 gene in Candida albicans, C. tropicalis, and C. krusei correlate with elevated caspofungin MICs uncovered in AM3 medium using the method of the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3092–3098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Desnos-Ollivier M., Dromer F., Dannaoui E. 2008. Detection of caspofungin resistance in Candida spp. by Etest. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2389–2392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garcia-Effron G., Lee S., Park S., Cleary J. D., Perlin D. S. 2009. Effect of Candida glabrata FKS1 and FKS2 mutations on echinocandin sensitivity and kinetics of 1,3-beta-D-glucan synthase: implication for the existing susceptibility breakpoint. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3690–3699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garcia-Effron G., Park S., Perlin D. S. 2009. Correlating echinocandin MIC and kinetic inhibition of fks1 mutant glucan synthases for Candida albicans: implications for interpretive breakpoints. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:112–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Katiyar S., Pfaller M., Edlind T. 2006. Candida albicans and Candida glabrata clinical isolates exhibiting reduced echinocandin susceptibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2892–2894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Laverdiere M., et al. 2006. Progressive loss of echinocandin activity following prolonged use for treatment of Candida albicans oesophagitis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:705–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pfaller M. A., et al. 2008. Correlation of MIC with outcome for Candida species tested against caspofungin, anidulafungin, and micafungin: analysis and proposal for interpretive MIC breakpoints. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2620–2629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]