Abstract

We investigated the interaction between the cross-reactive HIV-1 neutralizing human monoclonal antibody m18 with HIV-1YU-2 gp120 in order to understand how this antibody inhibits viral entry into cells. M18 binds to gp120 with high affinity (KD ≈ 5 nM) as measured by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). SPR analysis further showed that m18 inhibits gp120 interactions with both soluble CD4 as well as CD4-induced antibodies that have epitopes overlapping the coreceptor binding site. This dual receptor site antagonism, which occurs with equal potency for both inhibition effects, argues that m18 is not functioning as a mimic of CD4, in spite of the presence of a putative CD4-like loop formed by HCDR3 in the antibody. Consistent with this view, m18 was found to interact with gp120 in the presence of saturating concentrations of a CD4-mimicking small molecule gp120 inhibitor, suggesting that m18 does not require unoccupied CD4 Phe43 binding cavity residues of gp120. Thermodynamic analysis of the m18-gp120 interaction suggests that m18 stabilizes a conformation of gp120 that is unique from and less structured than the CD4-stabilized conformation. Conformational mutants of gp120 were studied for their impact on m18 interaction. Mutations known to disrupt the coreceptor binding region and lead to complete suppression of 17b binding had minimal effects on m18 binding. This argues that energetically important epitopes for m18 binding lie outside the disrupted bridging sheet region used for 17b and coreceptor binding. In contrast, mutations in the CD4 region strongly affected m18 binding. Overall, the results obtained in this work argue that m18, rather than mimicking CD4 directly, suppresses both receptor binding site functions of HIV-1 gp120 by stabilizing a non-productive conformation of the envelope protein. These results can be related to prior findings for the importance of conformational entrapment as a common mode of action for neutralizing CD4bs antibodies, with differences mainly in epitope utilization and extent of gp120 structuring.

During the initial stages of HIV-1 infection, attachment and fusion of the virus to the host cell membrane are mediated by the viral envelope spike. The spike structure is composed of a heterotrimeric complex of three glycoprotein 120 (gp120) and three glycoprotein 41 (gp41) subunits that associate through non-covalent interactions (1–4). During infection, gp120 initially interacts with CD4 expressed on T-cells and macrophages (5–9). Binding to CD4 leads to conformational structuring within gp120, facilitating interactions with an obligate coreceptor, either CCR5 or CXCR4 (10). Interaction with the coreceptor then induces further conformational changes within gp120 and gp41, exposing gp41 to the host membrane which ultimately leads to fusion of the virus and host cell membranes (11–24). As such, the development of entry inhibitors that target conserved regions of the envelope and block the initial attachment and fusion processes is an important strategy in combating the spread of HIV-1 (25). However, this has been impeded by extensive sequence variability between virus subtypes and the conformational masking of receptor binding sites within gp120 (26–31). Any effective HIV-1 entry inhibitor that targets gp120 must therefore recognize a site that is conserved throughout the isolates. A promising target for such entry inhibitors is the CD4 binding site (CD4bs) due to its absolute functional conservation among all isolates of HIV-1.

Broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (mAb) to the HIV-1 envelope have been found to be rare, and those that have been identified have been investigated in order to obtain both clues to vaccine design and insights into the envelope protein’s role in host cell entry by the virus (32–34). Representative broadly neutralizing antibodies that recognize envelope gp120 include the CD4bs antibody b12, outer domain directed 2G12, VRC01 that is directed at multiple neutralizing epitopes and spike-dependent PG9 and PG16. B12 binds to a region of gp120 that partially overlaps with the CD4 binding interface and prevents the formation of both the fully structured CD4bs and a structured bridging sheet for coreceptor binding (35). A similar mode of action has been elucidated for the less broadly neutralizing mAb F105 (36, 37). In contrast, the monoclonal antibody 2G12 binds to the outer domain of gp120 through interactions with carbohydrate groups on the exposed envelope surface. This antibody does not interfere with CD4 or coreceptor binding by monomeric gp120, but nonetheless inhibits viral entry, likely by effects on envelope function in the context of the virus spike (38–42). Recently, a highly potent CD4bs antibody, VRC01, was identified that appears to exert its neutralization breadth by partially mimicking CD4 and at the same time interacting at a glycosylation site (43, 44). Furthermore, a set of potent neutralizing antibodies, PG9 and PG16, have been identified that bind to envelope spike trimers, but not to gp120 monomers (45–47).

In spite of the observation of such antibodies as above, these have proven to be difficult to elicit as dominant antibody responses upon envelope protein vaccination, reflecting the ability of the virus to evade elimination by the immune system. Nonetheless, the fact that broadly neutralizing antibodies can be isolated indicates that their highly conserved binding sites are potential targets for developing compounds to halt HIV-1 entry. In addition, their modes of action can provide clues for designing vaccines that could elicit improved neutralizing responses.

In the current paper, we describe the characterization of m18, a monoclonal antibody against HIV-1 that was initially isolated through phage display technology, utilizing complexes of soluble CD4 (sCD4) and HIV-1 gp120 to select for tightly binding sequences (48–50). Previous results showed that Fab m18 was able to bind to HIV-1 envelope gp120 and to inhibit virus infection (48). We sought to characterize Fab m18 binding through biophysical assays in order to expand our understanding of how the antibody interaction suppresses gp120 function. This was achieved by combining surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments to investigate the kinetic and thermodynamic properties of the interaction between m18 and wild type HIV-1YU-2 gp120 (herein designated gp120) and various conformationally constrained mutants of the gp120 protein. M18, though classified as a CD4bs antibody, does not require unoccupied CD4 Phe43 binding pocket residues for gp120 interaction. Instead, the results argue that the major mode of gp120 inhibition occurs through interactions of the m18 paratope with structural elements outside the Phe43 binding pocket, leading to stabilization of a gp120 conformation with both of its receptor binding sites suppressed. The resulting phenomenon of dual receptor site inhibition has been observed as a recurrent theme for a number of neutralizing CD4bs antibodies (51).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Proteins

The expression plasmids, HIV-1YU-2 gp120 and HIV-1YU-2 S375W/T257S gp120 mutant, were kind gifts from Dr. Joseph Sodroski. The expression plasmid for HIV-1YU-2 core gp120 was a gift from Dr. Richard Wyatt. HIV-1YU-2 OD1 gp120 protein was provided by Dr. Joseph Sodroski and Dr. Xinzhen Yang. CHO-ST4.2 cells were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH from Dr. Dan Littman. IgG F105 was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH from Dr. Marshall Posner and Dr. Lisa Cavacini. The antibodies IgG b12 and IgG b6 were kindly provided by Dr. Dennis Burton. IgG 412d and IgG 48d were kindly provided by Dr. James E. Robinson. The monoclonal antibody, 17b, was purchased from Strategic Biosolutions, USA; D7324 was purchased from Aalto Bio Reagents Ltd., Ireland; F425 B4A1 was acquired from Dr. Marshall Posner and Dr. Lisa Cavacini.

HIV-1 gp120 Protein Expression

HIV-1YU-2 gp120, its mutants, and HIV-1YU-2core gp120, all in the expression vector pcDNA3.1, were produced as soluble protein in mammalian cells using the 293F Invitrogen protocol. Briefly, a one liter culture volume of freestyle human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293F) were grown to a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL under 7.4% CO2 in Gibco Freestyle 293F media (Invitrogen, CA). The cells were then transfected with 1 milligram of plasmid DNA per liter of culture using 293F Fectin (Invitrogen) and Opti-MEM I (Invitrogen, CA). The cells were grown at 37°C in 7.4% CO2 for five days, after which the supernatant was clarified and the protein was purified as outlined below.

HIV-1 gp120 Protein Purification

Wild type gp120 was purified through an F105 affinity column as previously described to obtain a homogeneous population for ITC experiments (52). This protein was then further purified through a Hiload 26/60 Superdex 200 (GE Healthcare) column to separate monomeric gp120 from misfolded and aggregated protein. Wild type and mutant gp120 proteins for SPR experiments were purified using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) through a C-terminal histidine tag. The clarified supernatant was passed through a column of nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose beads charged with nickel sulfate. Once the supernatant passed through, the column was washed repeatedly with 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl and 20 mM imidazole. The bound gp120 was eluted using 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl and 200 mM imidazole. All of the proteins were concentrated and exchanged into phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 0.01 M NaH2PO4, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.0) and stored at −80°C. SPR analysis of wild type gp120 purified through an affinity column versus an IMAC column showed little difference in the affinity measurements for sCD4, b12, 17b and Fab m18 (data not shown).

HIV-1 gp120 Mutagenesis

The D368R mutation of gp120 was made using the primers, 5′cccagcagcgggggcaggcccgagatcgtgacc3′ and 5′ggtcacgatctcgggcctgcccccgctgctggg3′ through basic mutagenic protocols (53–55). The I420R mutation was made using the primers, 5′accctgccctgccggcggaagcagatcatcaac3′ and 5′gttgatgatctgcttccgccggcagggcagggt3′ (56, 57). The I423M/N425K/G431E mutation was made in gp120 using the primers 5′tgccggatcaagcagatgatcaagatgtggcaggaggtggagaaggccatgtacgcc3′ and 5′ggcgtacatggccttgcccacctcctgccacatgttgatcatctgcttgatccggca3′ (58). The mutants, D5 and D9GG, were made based on constructs created by Rits-Volloch, et al (12). The D5 mutation deletes four residues, 206PK207 and 213IP214, from the β3-β5 loop sequence, 206PKVTFEPIP214, using the primer sets 5′atcacccaggcctgcgtgagcttcgagccc3′/ 5′gggctcgaagctcacgcaggcctgggtgat3′ and 5′gtgagcttcgagcccatccactactgcgcc3′/ 5′ggcgcagtagtggatgggctcgaagctcac3′, respectively. The D5 mutant was mutated further to create the D9GG mutant. Using the primers, 5′atcacccaggcctgcggcggcatccactactgcgcc3′ and 5′ggcgcagtagtggatgccgccgcaggcctgggtgat3′, the β3-β5 loop sequence, 206PKVTFEPIP214, was completely removed and replaced by two glycine residues. Other point mutations in gp120 were also made: P124A (5′gaccagagcctgaagGCCtgcgtgaagctgacc3′, 5′ggtcagcttcacgcaggccttcaggctctggtc3′), T278A (5′cggagcgagaacttcGCCaacaacgccaagacc3′, 5′ggtcttggcgttgttggcgaagttctcgctccg3′), N279A (5′agcgagaacttcaccGCCaacgccaagaccatc3′, 5′gatggtcttggcgttggcggtgaagttctcgct3′), N280A (5′gagaacttcaccaacGCCgccaagaccatcatc3′, 5′gatgatggtcttggcggcgttggtgaagttctc3′), A281G (5′aacttcaccaacaacGGCaagaccatcatcgtg3′, 5′cacgatgatggtcttgccgttgttggtgaagtt3′), K282A (5′ttcaccaacaacgccGCCaccatcatcgtgcag3′, 5′ctgcacgatgatggtggcggcgttgttggtgaa3′), T283A (5′accaacaacgccaagGCCatcatcgtgcagctg3′, 5′cagctgcacgatgatggccttggcgttgttggt3′) and R456A 5′ggcctgctgctgaccGCCgacggcggcaaggac3′, 5′gtccttgccgccgtcggcggtcagcagcaggcc3′). Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out in three rounds using standardized techniques (Stratagene, CA).

Fab m18 Production

The Fab m18 gene, contained in the phage display vector, pComb3x, was transformed into HB2151 cells (Maxim Biotech, CA). The transformed cells were grown in super broth media at 37°C until the optical density reached 0.8 absorption units. Protein expression was then induced with 2 mM IPTG and grown at 30°C for 18 hours. Cells were spun down and resuspended in PBS with 20 nM PMSF, 100 μM lysozyme, and 100 μM DNase VI. The cells were then sonicated at 50% power with repeated cycles of 15 seconds on and 10 seconds off for five minutes. The lysed cells were spun down at 18,000 rpm for 20 minutes and the supernatant was passed through a 0.2 μm filter. Fab m18 was affinity purified via protein G chromatography and eluted from the column with 0.1 M glycine, pH 2.5. The protein was exchanged into PBS and stored at −20°C.

Soluble CD4 Production

Soluble CD4 (sCD4) was produced from CHO-ST4.2 cells and contained the entire extracellular domain of the receptor. The soluble protein was secreted by the cells into the supernatant and purified as described previously (59).

Peptide Synthesis

The [F5W]CD4F23, a miniprotein mimic of CD4, was synthesized through solid-phase peptide synthesis using an ABI 433A peptide synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and purified through a C18 reverse phase HPLC column as previously reported (52). The sequence of [F5W]CD4F23 corresponds to the previously reported CD4F23 (60) with a tryptophan mutation at position five to facilitate quantification of the miniprotein (CNLHWCQLRCKSLGLLGKCAGSFCACV-NH2) by UV spectroscopy without disturbing its binding properties. MALDI mass spectroscopy was performed by the Wistar Institute Proteomics Facility (Philadelphia, PA) on the oxidized peptide and gave a mass of 2905.9 g/mol (the calculated value is 2906.3).

Surface Plasmon Resonance Binding Analysis

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assays were performed on a BIAcore 3000 instrument (GE Healthcare, USA). Ligands were immobilized onto a CM5 dextran sensor surface through standard amine coupling techniques using 0.2 M EDC and 0.05 M NHS, based on manufacturer protocols and as described previously (52). Briefly, the carboxymethyl dextran was activated by injecting 35 μL of the EDC/NHS solution over the surface at 5 μL/minute. The ligand was diluted to 0.01 μg/μL in 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5, and manually injected over the activated CM5 sensor surface until the appropriate amount of ligand (in response units or RU) was immobilized onto the surface. The reactive surface was then quenched by injecting 35 μL of 1 M ethanolamine-HCl, pH 8.0 over the surface at 5 μL/minute. A non-specific reference surface was created through immobilization of IgG 2E3, an anti-IL5 monoclonal antibody. This reference surface, along with buffer injections (PBS, pH 7.2, Roche Diagnostics GmbH), were used to correct for non-specific interactions and instrumental artifacts.

Direct binding interactions of gp120 and its mutants to sCD4, b12, Fab m18 and 17b were studied through SPR. Soluble CD4 (2000 RU), IgG b12 (700 RU), Fab m18 (400 RU) and IgG 17b (700 RU) were immobilized onto the surface of a CM5 chip. On average, immobilized Fab m18 is only 15% active due to the random orientation of the Fab molecules during the immobilization process. This does not affect the affinity measurements since inverting the assay and immobilizing gp120 on the surface yields the same affinity values for the m18-gp120 interaction (data not shown). Serial dilutions of gp120 and its mutants were made in PBS and injected over the Fab m18 surface at 50 μL/min with a 250 second association and up to 300 second dissociation. The 2E3, sCD4, m18 and b12 surfaces were then regenerated with a five second pulse of 1.3 M sodium chloride, 35 mM sodium hydroxide at 100 μL/minute. The 17b surface was regenerated with a five second pulse of 10 mM glycine, pH 1.5 at 100 μL/minute. Kinetic analysis of gp120 binding to sCD4, b12, m18 and 17b was performed by fitting the binding curves to a Langmuir 1:1 model using the BIAevaluation 4.0 program, with low residuals and Chi2. This analysis determined the average ka and kd values, which were then used to calculate the associated KA and KD values.

Competition assays were performed using SPR to study the effect of Fab m18 on gp120 interactions with sCD4 and 17b. During these experiments, sCD4 and 17b were immobilized onto a sensor surface and regenerated as stated above (52, 61). Increasing concentrations of m18 (4 to 500 nM) were premixed with a final concentration of 100 nM gp120 and then passed over the sensor surface to detect gp120 binding to the immobilized sCD4 and 17b. M18 and gp120 were premixed so that gp120 could bind to the Fab before being allowed to bind to sCD4 or 17b, allowing for true competition. If gp120 is allowed to bind to the immobilized sCD4, m18 cannot bind to this complex. Reverse experiments were also performed in which Fab m18 was immobilized and 100nM gp120 was premixed with either increasing concentrations of sCD4 or Fab 17b. During all the competition assays, each concentration series was run in triplicate. Due to the setup of the SPR experiments, the premixing times were variable for all of the samples, but this was found via repeat analyses to not affect the degree of competition for any given concentration throughout the duration of the experiments. In a similar assay, the ligands IgG F105, IgG b6, IgG 412d, IgG 48d, Fab X5, Fc M9, IgG D7324, and IgG B4A1 were all immobilized onto separate sensor surfaces to a maximum density of 600 response units and competition was studied in the same manner as above. IgG CG10 was immobilized onto a sensor surface to a maximum density of 1000 response units. Binding of this antibody to gp120 is fully dependent on the presence of sCD4. In order to obtain direct binding kinetics for gp120 to CG10, serial dilutions of gp120 (0 to 500 nM) were premixed with a final concentration of 600 nM sCD4 (to obtain 99% saturation of gp120) before being injected over the CG10 surface (62). These immobilized ligands were all regenerated with a five second pulse of 1.3 M sodium chloride, 35 mM sodium hydroxide at 100 μL/minute.

Competition analysis of NBD-556 (63) binding to gp120 and blocking Fab m18 interactions were performed using immobilized Fab m18 as stated above. Increasing concentrations of NBD-556 (up to 250 μM to reach 99.9% saturation of gp120) were premixed with a final concentration of 100 nM gp120 in 2% DMSO before being injected over the m18 surface at 50 μL/minute. Two percent DMSO was added to the buffer to solubilize NBD-556; this additive had negligible effects on gp120 as judged by control gp120 binding analysis in 2% DMSO and the absence of NBD-556 (data not shown). This experiment was repeated with [F5W]CD4F23, which was immobilized to the sensor surface of a CM5 chip through standard amine coupling procedures to a maximum density of 300 response units. The peptide surface was regenerated with a single five second pulse of 10 mM glycine, pH 1.5 at 100 μL/minute. The data were analyzed by plotting the maximum response at steady state against the concentration of NBD-556 in solution and then fitting to a four parameter equation through the BIAevaluation 4.0 program (59). This analysis yielded the half maximal binding inhibitory concentration (IC50).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

Isothermal titration calorimetric experiments were performed using a high-precision ITC200 titration calorimetric system from MicroCal LLC. (Northampton, MA). The calorimetric cell (~0.2 mL), containing gp120 at a concentration of about 3 μM dissolved in PBS (Roche Diagnostics GmbH), pH 7.4, was titrated with m18 dissolved in the same buffer. Fab m18 at a concentration of 30 μM was added in steps of 1.4 μL with pre-set intervals. All solutions were degassed to avoid any formation of bubbles in the calorimeter during stirring. The experiments were performed at 15, 20, 25, 30, and 35°C. The heat evolved upon injection of the antibody was obtained from the integral of the calorimetric signal. The heat associated with the binding reaction was obtained by subtracting the heat of dilution from the heat of reaction. The individual binding heats were plotted against the molar ratio, and the values for the enthalpy change (ΔH) and association constant, KA, were obtained by nonlinear regression of the data.

RESULTS

Inhibition of gp120 binding to both sCD4 and 17b by Fab m18

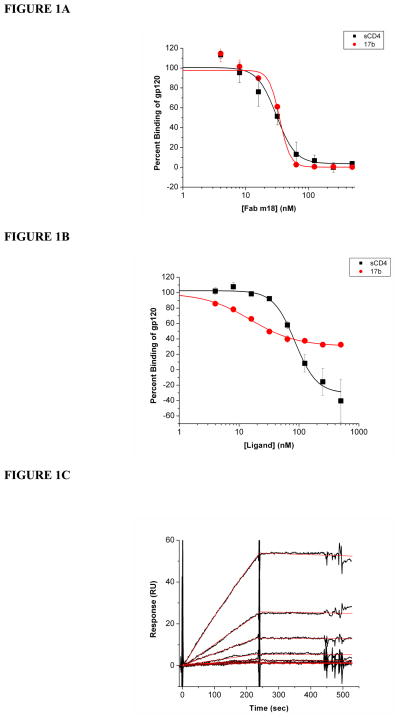

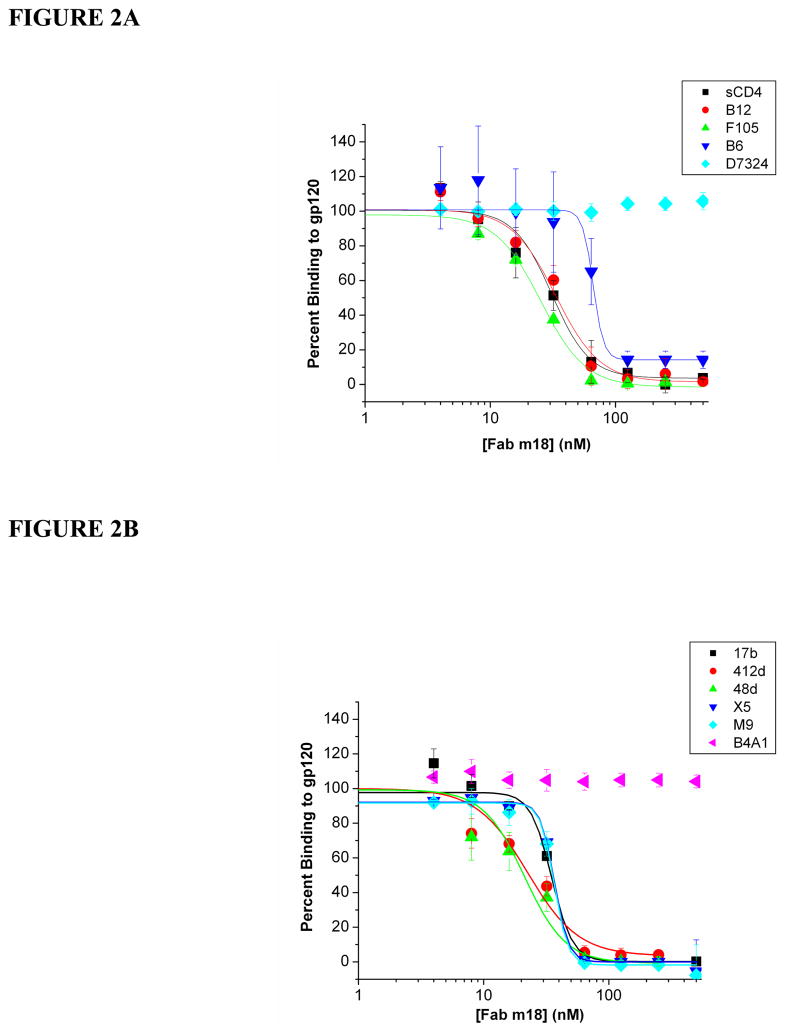

In order to understand how m18 binding affects the exposure of the receptor sites on gp120, we performed SPR competition analyses with sCD4 and mAb 17b. In experiments with monomeric gp120, we used 17b as a surrogate in lieu of the soluble coreceptor, CCR5 (6, 30, 52, 57, 61, 64, 65). These assays were carried out via SPR by immobilizing sCD4, 17b and 2E3 (66) onto a sensor surface and injecting a constant concentration of gp120 (100 nM) premixed with increasing concentrations of Fab m18. Control experiments were performed to verify that Fab m18 does not interact with immobilized sCD4 or 17b (data not shown). Figure 1A shows that, as the concentration of Fab m18 increased, the binding of gp120 to both sCD4 and 17b decreased. From these inhibition curves, we determined the relative IC50 values for m18 inhibiting sCD4 and 17b binding to gp120 were 33.0 nM (±3.6) and 36.0 nM (±3.6), respectively. These data indicate that m18 binds to gp120 in a manner that reduces its interaction to both of the functionally important receptor sites. The reverse experiment was also performed to show that sCD4 inhibited gp120 interactions to Fab m18 with an IC50 value of 96.0 nM (±12) but Fab 17b did not completely inhibit gp120 interactions with m18 (Figure 1B). To verify that 17b incompletely inhibited m18 binding, saturation analysis was performed. Increasing concentrations of gp120 were saturated with IgG 17b before being passed over immobilized Fab m18. Gp120 interactions with m18 were reduced ten-fold by 17b binding (Figure 1C). In order to understand if this inhibition was specific to the CD4 and coreceptor sites, we performed competition analyses with a number of other CD4bs and CD4i (CD4-induced site) monoclonal antibodies (Figure 2, Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1, and Supplementary Table 1) (35, 37, 57, 65, 67–69). Fab m18 suppressed gp120 binding to all the CD4bs and CD4i antibodies, but did not block gp120 binding to antibodies specific to the C-terminus and the tip of the V3 loop. We also tested m18 competition with mAb CG10 as a control for the 17b competition effect. CG10 binds to the CD4i site on gp120 with complete CD4 dependence (15, 70, 71). When a competition experiment was performed with m18, there was no detectable binding of gp120 or the gp120-m18 complex to CG10, indicating that the coreceptor site is not available in the m18-bound gp120. CD4 independent binding of CG10 to gp120 was not seen, as shown in Supplementary Figure 2. In the presence of saturating sCD4, gp120 bound to CG10 with 1.5 nM affinity. Overall, these competition experiments further confirm that Fab m18 suppresses interaction at both gp120 receptor sites.

Figure 1.

(A) Fab m18 inhibition of gp120 binding to (■) sCD4 and (

) mAb 17b. Serial dilutions of Fab m18, from 0 to 500 nM, were premixed with a final concentration of 100 nM gp120 before being passed over immobilized sCD4 and 17b. The maximum response at steady state for each concentration of Fab m18 was taken and these values were then fit to a four-parameter equation, through the BIAevaluation program, to determine the IC50 values for m18 inhibition of sCD4 and 17b. (B) Serial dilutions of CD4 (■) and Fab 17b (

) mAb 17b. Serial dilutions of Fab m18, from 0 to 500 nM, were premixed with a final concentration of 100 nM gp120 before being passed over immobilized sCD4 and 17b. The maximum response at steady state for each concentration of Fab m18 was taken and these values were then fit to a four-parameter equation, through the BIAevaluation program, to determine the IC50 values for m18 inhibition of sCD4 and 17b. (B) Serial dilutions of CD4 (■) and Fab 17b (

), from 0 to 500 nM, were premixed with a final concentration of 100 nM gp120 before being passed over immobilized Fab m18. The maximum response at steady state for each concentration of sCD4 and 17b were taken and these values were then fit to a four-parameter equation, through the BIAevaluation program, to determine the IC50 value for sCD4 (96 nM ± 12). 17b inhibition of m18 could not be determined. These competition data shown are in percent gp120 binding to the sCD4 and IgG 17b surfaces, respectively, and 100 nM gp120, 0 nM Fab m18 represents 100% binding to the surface. (C) M18 (600RU) was immobilized onto a CM5 sensor chip via a BIA3000 instrument. Increasing concentrations of gp120 premixed with a fixed concentration of 1 μM IgG 17b were passed over the surface to obtain these response curves (black) and the data were fit to a Langmuir 1:1 binding model (red) using the BIAevaluation program. The averages of the association and dissociation rates were used to determine the overall affinity for these protein-protein interactions. The affinity of 17b saturated gp120 binding to m18 is 49.0 nM (ka = 1.3 (±0.9) × 103 M−1s−1, kd = 6.2 (±4.1) × 10−5 s−1). Buffer injections and control surface binding were subtracted out of each curve. The data are plotted through the Origin 7 program.

), from 0 to 500 nM, were premixed with a final concentration of 100 nM gp120 before being passed over immobilized Fab m18. The maximum response at steady state for each concentration of sCD4 and 17b were taken and these values were then fit to a four-parameter equation, through the BIAevaluation program, to determine the IC50 value for sCD4 (96 nM ± 12). 17b inhibition of m18 could not be determined. These competition data shown are in percent gp120 binding to the sCD4 and IgG 17b surfaces, respectively, and 100 nM gp120, 0 nM Fab m18 represents 100% binding to the surface. (C) M18 (600RU) was immobilized onto a CM5 sensor chip via a BIA3000 instrument. Increasing concentrations of gp120 premixed with a fixed concentration of 1 μM IgG 17b were passed over the surface to obtain these response curves (black) and the data were fit to a Langmuir 1:1 binding model (red) using the BIAevaluation program. The averages of the association and dissociation rates were used to determine the overall affinity for these protein-protein interactions. The affinity of 17b saturated gp120 binding to m18 is 49.0 nM (ka = 1.3 (±0.9) × 103 M−1s−1, kd = 6.2 (±4.1) × 10−5 s−1). Buffer injections and control surface binding were subtracted out of each curve. The data are plotted through the Origin 7 program.

Figure 2.

Fab m18 inhibition of gp120 binding to various antibody ligands of HIV-1. (A) Fab m18 inhibition of gp120 binding to sCD4 and CD4bs mAbs as well as an antibody to the C-terminus of gp120: (■) sCD4, (

) mAb B12, (

) mAb B12, (

) mAb F105, (

) mAb F105, (

) mAb B6 and (

) mAb B6 and (

) mAb D7324. (B) Fab m18 inhibition of gp120 binding to coreceptor site antibodies and one antibody specific for the tip of the V3 loop: (■) mAb 17b, (

) mAb D7324. (B) Fab m18 inhibition of gp120 binding to coreceptor site antibodies and one antibody specific for the tip of the V3 loop: (■) mAb 17b, (

) mAb 412d, (

) mAb 412d, (

) mAb 48d, (

) mAb 48d, (

) mAb X5, (

) mAb X5, (

) mAb M9 and (

) mAb M9 and (

) mAb B4A1. Serial dilutions of Fab m18, from 0 to 500 nM, were premixed with a final concentration of 100 nM gp120 before being passed over the immobilized ligands. The maximum response at steady state for each concentration of Fab m18 was taken and these values were then fit to a four-parameter equation, through the BIAevaluation program, to determine the IC50 values for m18 inhibition. The data shown are in percent gp120 binding to the immobilized ligand surfaces, respectively, with 100 nM gp120, 0 nM Fab m18 representing 100% binding to the surface. The data are plotted through the Origin 7 program.

) mAb B4A1. Serial dilutions of Fab m18, from 0 to 500 nM, were premixed with a final concentration of 100 nM gp120 before being passed over the immobilized ligands. The maximum response at steady state for each concentration of Fab m18 was taken and these values were then fit to a four-parameter equation, through the BIAevaluation program, to determine the IC50 values for m18 inhibition. The data shown are in percent gp120 binding to the immobilized ligand surfaces, respectively, with 100 nM gp120, 0 nM Fab m18 representing 100% binding to the surface. The data are plotted through the Origin 7 program.

Table 1.

Direct Binding Kinetics for Gp120 Interactions with Monoclonal Antibody Ligands of HIV-1 and IC50 Values for Fab m18 Inhibition of Gp120 Interactions with these Ligands, as Determined by SPR Analysis. All values are shown in nanomolar. NI indicates no inhibition detected.

| Protein | sCD4 | b12 | F105 | b6 | 17b | 412d | 48d | X5 | M9 | D7324 | B4A1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KD (nM) | 10.5 | 46.6 | 34.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 3.2 | 0.7 | 10.2 | 32.6 |

| IC50 (nM) | 33.0 ± 3.6 | 32.3 ± 0.6 | 25.5 ± 1.6 | 32.7 ± 1.2 | 36.0 ± 1.2 | 25.2 ± 4.1 | 22.6 ± 7.1 | 37.6 ± 3.2 | 37.5 ± 3.0 | NI | NI |

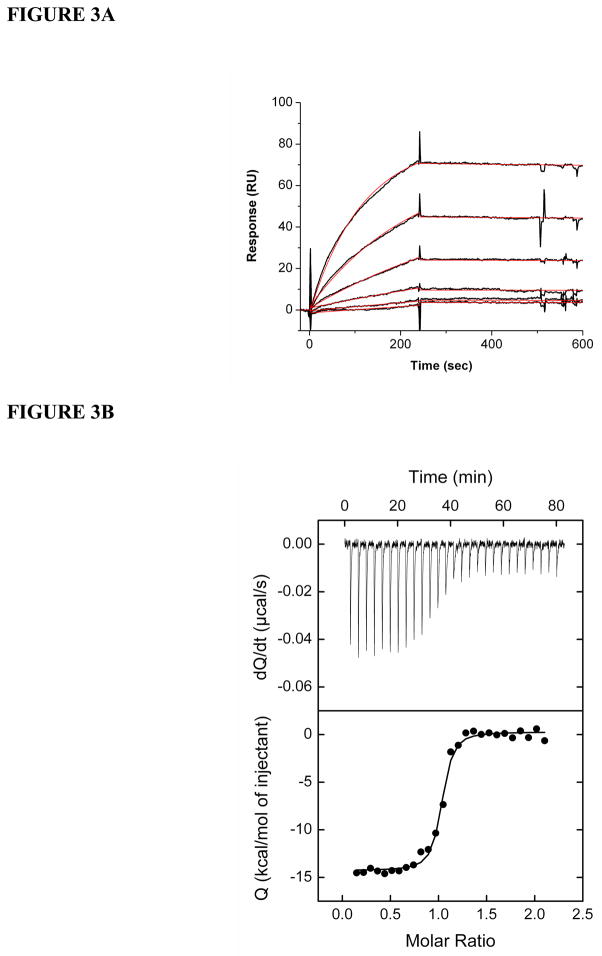

Reduced structuring of gp120 upon high affinity Fab m18 binding

Previous ELISA studies demonstrated that m18 binds to various gp120s with high affinity (48). Here, we measured the kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of this interaction. SPR allows for quantification of the individual rate constants (kon and koff) that contribute to the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD). We immobilized gp120 and a control protein (IgG 2E3) onto the sensor surface of a CM5 chip and injected concentrations of Fab m18 ranging from 4 to 500 nM over these surfaces. We found that m18 binds to gp120 with low nanomolar affinity (KD = 4.8 nM) (Figure 3a, Table 2), consistent with previously published data (48). The m18-gp120 interaction was characterized by a relatively fast association rate (ka = 3.3 (±0.7) × 104 M−1s−1) and a very slow dissociation rate (kd = 1.6 (±0.3) × 10−4 s−1). Experiments were performed by reversing the orientation of the ligands, immobilized Fab m18 and passing over concentrations of gp120, and revealed similar interaction kinetics (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Gp120 binding to Fab m18 by SPR and ITC. (A) Fab m18 was immobilized onto a CM5 sensor chip via a BIA3000 instrument. Increasing concentrations of gp120 were passed over the surface to obtain these response curves (black). These experiments were repeated a minimum of three times and each set was fit to a Langmuir 1:1 binding model (red) using the BIAevaluation program. The averages of the association and dissociation rates were used to determine the overall affinity for these protein-protein interactions. Buffer injections and control surface binding were subtracted out of each curve. The sensorgrams and the fits are represented through the Origin 7 program. (B) Microcalorimetric titration of 30 μM Fab m18 into a 2 μM solution of gp120. This titration was performed at 25°C in PBS (pH 7.4) and repeated three times. The data were fit using the Origin program.

Table 2.

Direct Binding Affinities for Gp120 Wild Type and Mutant Proteins to sCD4, IgG b12, IgG 17b and Fab m18 as Determined by SPR Analysis. KD values are shown in nanomolar.

| Protein | Target | sCD4 | b12 | 17b | m18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YU-2 gp120 wt | 10.5 | 46.6 | 1.8 | 4.8 | |

| S375W/T257S | CD4bs | 0.9 | 75.5 | 3.5 | 6.0 |

| D368R | No Binding | No Binding | 1.2 | No Binding | |

| D5 | CD4i | 19.4 | 21.7 | No Binding | 2.4 |

| D9GG | 26.1 | 31.9 | No Binding | 16.0 | |

| I420R | 24.8 | 182.0 | No Binding | 17.9 | |

| I423M/N425K/G431E | CD4bs and CD4i | 78.1 | 74.9 | No Binding | 3.6 |

| OD1 | Outer Domain | No Binding | 53.8 | No Binding | No Binding |

| YU-2 core | Variable Loops | 20.4 | 51.9 | 551.0 | 0.2 |

We employed isothermal titration calorimetry to thermodynamically characterize the binding of Fab m18 to gp120 (Figure 3b). M18 binds to gp120 with an affinity of 6.2 nM. The values for the enthalpy and entropy of binding for m18 interactions with gp120 at 25°C are −14.6 kcal/mol and −11.4 cal/K*mol, respectively, and the heat capacity change for this interaction is −0.56 kcal/K*mol. The enthalpy value for m18 binding to gp120 at 35°C is −19.2 kcal/mol. The calculated enthalpy and entropy values for this interaction at 37°C are −21.3 kcal/mol and −3.2 cal/K*mol, respectively. These thermodynamic values suggest that m18 induces conformational structuring in gp120 that is far less than that observed for CD4 though greater than that observed for the broadly neutralizing mAb b12 (see Discussion)

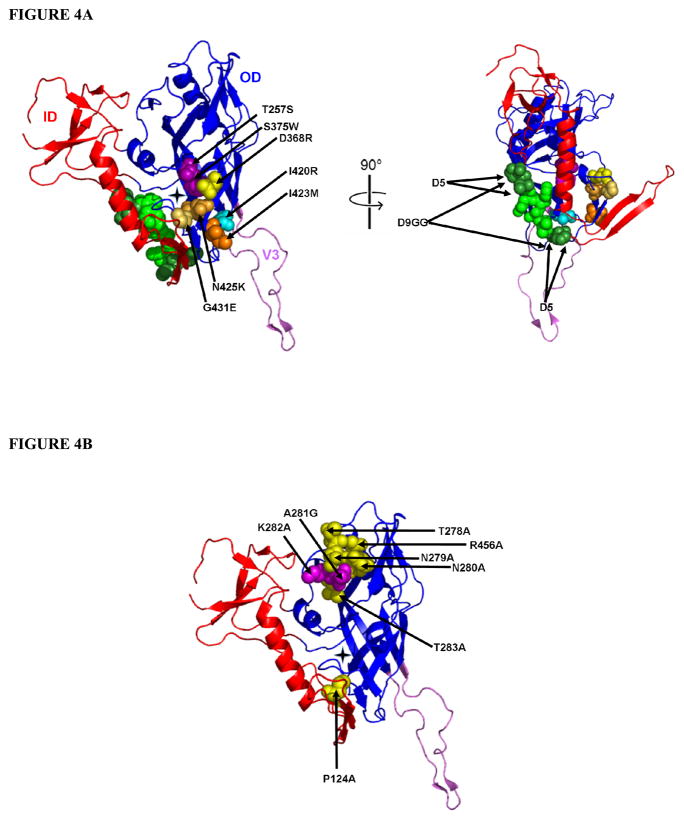

Fab m18 binding to conformational mutants of gp120

The similarities between the IC50 values for m18 competition with CD4 and 17b binding (Figure 1A) and the 1:1 stoichiometry of the m18-gp120 interaction determined through ITC (Figure 3B) argue that the effects at both receptor sites are due to a single m18 binding process. In order to better understand the structural elements at the CD4 and CD4i binding sites that contribute to m18 binding, we introduced mutations in gp120 that disrupt these sites individually. SPR analysis was performed in which increasing concentrations of these mutants, from 4 to 500 nM, were passed over a CM5 sensor surface with immobilized Fab m18 and the non-specific control, 2E3. We sought to determine if constraining the conformation of one receptor site could disrupt m18 interaction (Table 2). All of the mutant proteins were validated for functionality using sCD4, 17b, and b12 (Figure 4, Supplementary Figure 3, Supplementary Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

This figure represents the core structure of HIV-1JRFL gp120 with the V3 loop and a black star denotes the nexus of the CD4 Phe 43 binding cavity. Residues mutated to produce conformational constraints on YU-2 gp120 are highlighted in (A). In red is the inner domain (ID) of core gp120 and in blue is the outer domain (OD), which also consists of the V3 loop shown here in violet. Highlighted in magenta are the residues (T257S and S375W) which enhances the activated conformation of gp120 (58, 72). Highlighted in yellow is D368R, which disrupts the CD4 binding site without disrupting the coreceptor site (37, 53–55, 65, 73–76). In cyan is I420R, which has been show to disrupt the coreceptor site without disrupting the CD4 binding site (56, 57). The triple mutant, I423M/N425K/G431E, is shown in shades of orange and have been shown to disrupt both receptor sites simultaneously (58). The deletion mutants, D5 (in dark green) and D9GG (green and dark green), were made based on constructs created by Rits-Volloch, et al (12) and have been shown to prevent the formation of the bridging sheet. The D5 mutation deletes four residues, 206PK207 and 213IP214, from the β3-β5 loop sequence, 206PKVTFEPIP214. To create the D9GG mutant, the β3-β5 loop sequence, 206PKVTFEPIP214, was completely removed and replaced by two glycine residues. Our studies with the outer domain were with the full length YU-2 gp120 protein and not the truncated version shown here. The full length OD consists of what is represented in this figure in blue, the V3 loop (shown in violet) and the full V4 loop, which is truncated in this structure. The core YU-2 gp120 structure studied in this work consists of the inner domain (red), the outer domain (blue) and does not include the V3 loop shown in this figure. The data for Fab m18 binding to these mutant and truncated YU-2 gp120s are represented in Table 2. (B) Alanine mutants of YU-2 gp120 were made which were not previously studied with Fab m18. In yellow are residues which, when mutated to an alanine, had similar or better affinity to Fab m18 in comparison to wild type YU-2 gp120. In magenta are residues, when mutated to an alanine, have greater than a fivefold reduction in affinity to Fab m18. The data for these interactions are represented in Table 3. The crystal structure represented here is of JRFL gp120, PBD code 2B4C (68). The residues are numbered according to the HXBc2 gp120 core protein crystal structure (65). The residues are those found in YU-2 gp120 and all of the mutations were created in YU-2 gp120.

The first set of mutations altered the CD4bs by either enhancing or disrupting receptor binding. S375W/T257S is a mutant that enhances the activated conformation of gp120 and binds to immobilized sCD4 with a ten fold increase in affinity (58, 72). In contrast, Fab m18 affinity was not affected by this mutation. We also studied the D368R mutation, which abolishes critical contacts in the CD4bs while leaving the coreceptor site intact (37, 53–55, 65, 73–76). Direct binding analysis of D368R gp120 (up to 5 μM) to immobilized Fab m18 indicated that m18 cannot bind to this mutant.

The second set of mutations disrupt coreceptor binding, but not sCD4 binding. These mutants include D5 and D9GG, which have constraints in the β3-β5 loop that restrict the formation of the bridging sheet (12, 65), and I420R, which disrupts a key contact in CCR5 binding (13, 57, 74). Direct binding analysis showed that Fab m18 can bind to all three of these mutants with high affinity. From these data, the relationship of the m18 binding site to the CD4 and coreceptor binding sites appear to be asymmetric, as reflected by the different extents of m18 interactions to mutations made to disrupt these specific sites.

The functional outer domain of gp120 (OD1), I423M/N425K/G431E, and core gp120 were used to expand our binding site characterizations. Truncation of gp120 to create OD1 (77) abrogates sCD4 and 17b binding while retaining the b12 epitope, shown through SPR (35). In addition, Fab m18 did not bind detectably to OD1 (37), up to 10 μM in our SPR experiments. I423M/N425K/G431E is a triple mutant in the β20-β21 loop which has reduced binding to CD4 and no binding to the coreceptor, but retains binding to b12 (58). These point mutations had no effect on m18 binding to gp120. Finally, we tested m18 binding to core gp120 to determine the necessity of the variable loops for m18 binding (65, 67, 78). Core gp120 can bind to sCD4 and b12, but binds poorly to 17b in the absence of sCD4 (35, 37, 60, 69). We show that m18 binds to gp120 core (35, 37), with a high affinity, indicating that the variable loops do not play a role in the m18 binding epitope. Overall, these data indicate that disruptions to the general CD4bs directly affect m18 binding, whereas disruptions to the 17b binding site have minimal effects on m18 binding. These data argue that the suppression of 17b binding by m18 is likely due to indirect conformational effects.

In conjunction with conformational mutants, we examined the effects of gp120 mutations to m18 binding at suspected contact sites. We compared the CD4 contact residues on gp120, as determined by crystal structure, with the mutational analysis performed to determine the m18 binding site on gp120 (50, 65). We found eight residues that were not previously tested for m18 binding (P124, T258, N279, N280, A281, K282, T283 and R456), but were found to form part of the CD4 interface in the crystal structure. We created alanine point mutations at these sites, with the exception of A281, which was mutated to a glycine. Direct binding analysis of the single site mutants with both CD4 and m18 were performed (Table 3). Interestingly, the single site gp120 mutants had a different pattern of effects on the two ligands, though all effects were relatively muted in comparison to results with conformational mutants. M18 had reduced affinity for A281G and K282A while these mutations had no significant effect on sCD4 binding. Overall, these data suggest that the effects of contact site mutations on m18 and CD4 binding are not the same, further confirming the notion that m18 is not simply a CD4 mimic.

Table 3.

Direct Binding Affinities for Gp120 Alanine Mutant Proteins to sCD4 and Fab m18 as Determined by SPR Analysis. KD values are shown in nanomolar.

| Protein | sCD4 (nM) | Fab m18 (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| WT | 10.5 | 4.8 |

| P124A | 26.2 | 0.4 |

| T278A | 7.3 | 0.01 |

| N279A | 34.6 | 0.01 |

| N280A | 6.8 | 0.6 |

| A281G | 12.3 | 58.4 |

| K282A | 11.9 | 28.3 |

| T283A | 16.7 | 0.02 |

| R456A | 11.3 | 3.5 |

Incomplete blockade of Fab m18 binding to gp120 by the small CD4 mimic, NBD-556

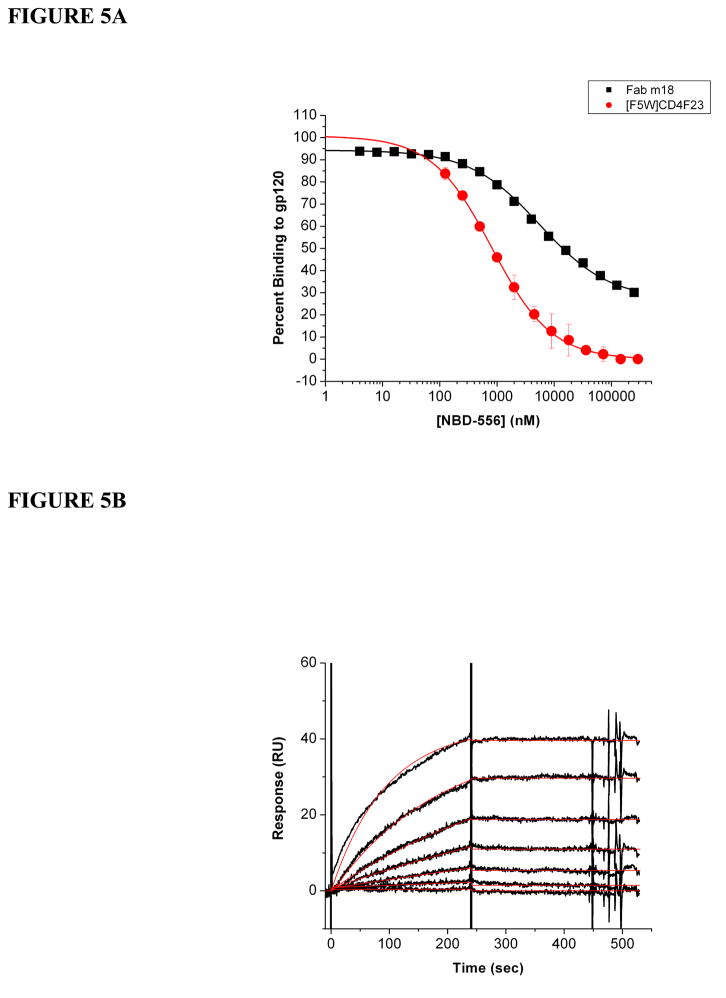

We have shown that Fab m18 binds to gp120 with high affinity. This binding is dependent upon the conformational integrity of the CD4bs, as opposed to the coreceptor binding site. However, what parts of the CD4 binding site are used by m18 is not evident from these results. We utilized the small non-peptidic CD4 mimic, NBD-556, to probe this question further. NBD-556 binds within the Phe43 cavity of gp120 and directly competes with CD4 for binding to gp120 (63, 79). A fixed concentration of gp120 was premixed with increasing concentrations of this compound before being injected over immobilized Fab m18. Even at a concentration expected to achieve 99% saturation, NBD-556 still could not reduce gp120 binding to m18 below 30% (Figure 5A). This suppressed inhibition is unlikely to be due to gp120 heterogeneity since NBD-556 competition of gp120 binding to an immobilized CD4 mimic, [F5W]CD4F23 revealed complete competition in this case (Figure 5A). Saturation analysis with NBD-556 indicates that it does not reduce the affinity of gp120 for m18 binding (Figure 5B). It appears that part of the m18 epitope is still intact on the gp120-NBD-556 complex. While these data indicate a partial suppression of m18 binding by NBD-556, it is clear that the m18 binding site is not dependent on the Phe43 binding cavity.

Figure 5.

(A) NBD-556 inhibition of gp120 binding to Fab m18 (■) and to [F5W]CD4F23 (

). Serial dilutions of NBD-556 (from 4 nM to 250 μM) were premixed with a final concentration of 100 nM gp120 before being passed over a CM5 surface with immobilized Fab m18 and [F5W]CD4F23. At its maximum concentration, NBD-556 only reduces gp120 binding to m18 to 30%. NBD-556 was able to inhibit gp120 binding to [F5W]CD4F23 with and IC50 value of 784 (±55) nM. (B) M18 (600RU) was immobilized onto a CM5 sensor chip via a BIA3000 instrument. Increasing concentrations of gp120 premixed with a fixed concentration of 100 μM NBD-556 in a 2% DMSO buffer were passed over the surface to obtain these response curves (black) and the data were fit to a Langmuir 1:1 binding model (red) using the BIAevaluation program. The averages of the association and dissociation rates were used to determine the overall affinity for these protein-protein interactions. NBD-556 does not reduce the affinity of gp120 to m18 (ka = 3.2 (±0.9) × 104 M−1s−1, kd = 9.6 (±0.1) × 10−5 s−1, KD = 3.0 nM). Buffer injections and control surface binding were subtracted out of each curve. These experiments were repeated a minimum of three times and the data are plotted through the Origin 7 program.

). Serial dilutions of NBD-556 (from 4 nM to 250 μM) were premixed with a final concentration of 100 nM gp120 before being passed over a CM5 surface with immobilized Fab m18 and [F5W]CD4F23. At its maximum concentration, NBD-556 only reduces gp120 binding to m18 to 30%. NBD-556 was able to inhibit gp120 binding to [F5W]CD4F23 with and IC50 value of 784 (±55) nM. (B) M18 (600RU) was immobilized onto a CM5 sensor chip via a BIA3000 instrument. Increasing concentrations of gp120 premixed with a fixed concentration of 100 μM NBD-556 in a 2% DMSO buffer were passed over the surface to obtain these response curves (black) and the data were fit to a Langmuir 1:1 binding model (red) using the BIAevaluation program. The averages of the association and dissociation rates were used to determine the overall affinity for these protein-protein interactions. NBD-556 does not reduce the affinity of gp120 to m18 (ka = 3.2 (±0.9) × 104 M−1s−1, kd = 9.6 (±0.1) × 10−5 s−1, KD = 3.0 nM). Buffer injections and control surface binding were subtracted out of each curve. These experiments were repeated a minimum of three times and the data are plotted through the Origin 7 program.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have demonstrated that mAb m18 inhibits viral entry into cells for a range of HIV-1 subtypes (48). Structural and sequence homology between the HCDR3 region of m18 and the Phe43 loop of CD4 led to the possibility that m18’s specificity might be derived from mimicking CD4 (50). In the initial phase of this project, we sought to examine the extent of m18’s binding properties in comparison to those of CD4. Using SPR analysis, we observed that m18 acted as a dual receptor site inhibitor, suppressing binding of gp120 to both sCD4 and the coreceptor surrogate, mAb 17b (Figure 1A). The suppression of 17b binding is the opposite of the enhancement observed with CD4 and CD4 mimics (52). This dual antagonism indicates that m18 is not simply a CD4 mimic. We followed up on these initial observations to better understand the mechanism by which m18 binds to and inhibits gp120.

The current investigation revealed that m18 stabilizes a conformation of gp120 that is significantly different and much less structured than the CD4- and F105-bound conformations of gp120 (29). The binding of CD4 to gp120 is characterized by unusually large changes in favorable enthalpy and unfavorable entropy (ΔH = −34.5 kcal/mol; ΔS = −81 cal/K*mol) and a large negative heat capacity change (ΔCp) (−1.8 kcal/K*mol). This thermodynamic signature originates from the large structuring of residues in gp120 that takes place upon binding to CD4 and leads to the stabilization of the coreceptor binding site (10, 63, 80). The magnitude of CD4-induced structuring of gp120 reflects the significant amount of disorder of gp120 in its unliganded state. We can surmise that m18 stabilizes a partially structured state. Antibody ligands that inhibit gp120 activation typically do not induce large conformational structuring and stabilize non-activated conformations of gp120 (10, 29, 35, 37, 65, 81). The thermodynamic signature of b12 binding to gp120, supported by the crystal structure of the gp120-b12 complex, suggests that no major conformational structuring takes place in gp120 upon binding to b12 (35). In the current work, ITC analysis revealed that the change in entropy and enthalpy for the m18-gp120 interaction is much smaller than that of CD4 binding to gp120 (Figure 3B). These data, along with the small change in heat capacity (ΔCp), indicate that m18 is similar to other neutralizing antibodies such as b12, which binds to gp120 with more limited structuring than CD4 (29). From prior results, it has been argued that, if the binding of CD4 to gp120 did not induce any structuring, a change in heat capacity of −0.4 kcal/K*mol would be expected. This is close to what is experimentally observed for m18. Hence m18 appears to stabilize a conformation of gp120 that is closer to the unliganded state than the CD4-activated state (27).

In our initial experiments, we observed that m18 suppressed the activation of the coreceptor site. To further define this interaction, we measured m18 interactions with gp120 containing conformational mutations at the coreceptor binding site. Using these conformational mutants of gp120, we found that the m18 binding site was not affected by perturbations to the coreceptor site. We found that these gp120 mutants bound m18 to a similar extent as to unmodified gp120. This is opposite to the finding that CD4i antibodies such as 17b have essentially no binding to the coreceptor site mutants (Table 2). Furthermore, competition experiments with 17b showed that, even at saturating levels of this antibody, gp120 interactions with m18 were not completely inhibited (Figure 1B and 1C). These data indicate that m18 is not interacting directly with the coreceptor binding site. Overall, m18 interactions with these specific gp120 mutants argue that m18 does not require a structured coreceptor site and that the bridging sheet is not stabilized in the m18-gp120 complex.

Previous work by Zhang et al (48) and Prabakaran et al (50), as well as our competition analyses, suggest a strong linkage between the m18 and CD4 binding sites. Mutants of gp120 were studied to understand the specificity of this linkage (Table 2). The gp120 mutant, D368R, which suppresses CD4 binding, also does not bind m18. In contrast, m18’s interaction with the S375W/T257S mutant of gp120, which is thought to enhance the activated conformation of gp120, is similar to that of unmodified gp120. The triple mutant, I423M/N425K/G431E, was made to disrupt both receptor sites. Although sCD4 had reduced binding to this mutant gp120, m18 retained full binding. Although these data indicate that m18 is a CD4bs-like mAb, they also further distinguish m18 from CD4. These data are consistent with the m18 binding site being located outside of the Phe43 binding pocket in gp120. The latter conclusion can also be drawn from the results of competition analysis with NBD-556, a low molecular weight compound which binds in the Phe43 cavity (63, 79). Competition of gp120 by this compound did not prevent m18 binding, although it was able to completely block a CD4 mimic, [F5W]CD4F23, from binding to gp120 (Figure 4). The current experiments cannot distinguish the extent to which m18 binding may physically occlude parts of the CD4 binding site as opposed to conformational occlusion. The latter could occur through stabilization of gp120 into a conformation in which the receptor binding site is structurally disrupted. Nonetheless, the cumulative binding properties of m18 argue that this molecule is not simply a mimic of CD4 and does not utilize the Phe43 binding cavity.

Truncates of gp120 were also studied to further isolate the structural requirements for m18 binding (Table 2). Of the mutants tested, we detected no binding of m18 to OD1, leading us to conclude that m18 requires the inner domain in some fashion. This is different for the case of b12, which binds to OD1. We also showed through SPR assays that m18 interactions with core gp120 are slightly enhanced in comparison to the wild type protein, indicating that not only are the variable loops unnecessary for m18 binding, but their removal may enhance m18’s accessibility to its binding site. These truncates lead us to the conclusion that m18 binds to the conserved core of the envelope, but in a manner which requires the inner domain of gp120. From these data and the mutagenic data published by Prabakaran et al (50), we hypothesize that m18 may be binding to a site located at the interface of these two domains of gp120.

Our results with m18 argue that there are similarities between its mode of action and those of the antibodies b12, b13 and F105. Gp120 complexes with the latter antibodies have been characterized by x-ray diffraction analysis (35, 37), whereas m18 has not. Nonetheless, our results suggest that m18, similar to the other antibodies, stabilizes a non-activated conformational state of gp120. Using SPR analysis, m18 was shown to inhibit gp120 interactions at the coreceptor site, similar to that observed previously for other CD4bs antibodies (51). From our ITC data, the extent of m18-induced gp120 conformational structuring lies between those imposed by b12 and F105 and is far less than that induced by CD4 (29). It must be noted that the m18-gp120 interactions that have been obtained utilize the soluble form of the envelope rather than the trimeric spike as it would exist on the viral particle. Hence, at this stage, we cannot easily predict the relative importance of binding site blockade versus conformational effects in m18’s antiviral mode of action.

In spite of the frequent denotation of antibodies, such as b12, as competitive inhibitors of gp120 and similarities in m18 and b12 modes of action, we believe that conformational effects also tie together m18 with other members of this class of antibody inhibitors. Certainly, an attractive feature of antibodies which resemble b12 is their specificity for the conserved and functionally critical CD4 binding region of gp120. Indeed, at present, we cannot structurally define the binding site in gp120 for m18, including how it relates to the CD4 binding site. Nonetheless, at least for the case of m18, the term “competitive” obscures the finding that this antibody does not require an open Phe43 binding cavity and, hence, is not a CD4 mimic. Instead, it is conformational change that underlies the common action of m18, many neutralizing antibodies and CD4 itself to disrupt or activate the coreceptor site. In the case of m18 and other neutralizing CD4bs antibodies, this essentially leads to overall inactivated conformations of gp120. Prior data have shown that antibodies that entrap gp120 into partially structured conformations can exhibit strong neutralization effects (29). M18 interaction with gp120 has a thermodynamic signature that defines it as a low-structuring antibody, though not as low as the prototypic b12. Interestingly, the recently identified VRC01 is strongly neutralizing and yet induces a large degree of gp120 structuring (43). While the detailed thermodynamic signatures may vary among these different cases, it is likely that antibodies that can bind envelope gp120 and entrap inactive conformations can be utilized to develop effective HIV-1 antagonists.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Institute of Health grant P01 GM 56550, CHAVI U19AI067854-04, and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. We are grateful to Dr. Joseph Sodroski for providing us with the DNA construct for full length gp120, to Dr. Joseph Sodroski and Dr. Xinzhen Yang for providing us with the protein, OD1, to Dr. Richard Wyatt for providing us with DNA construct for core gp120, to Dr. Dennis Burton for providing us with IgG b12 and IgG b6 and to Dr. James E. Robinson for providing us with IgG 412d and IgG 48d. We also thank Dr. Bradford Jameson, Dr. Patrick Loll, Dr. Fred Krebs, Dr. James Hoxie, Dr. Peter Kwong and Dr. Ponraj Prabakaran for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- AIDS

acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- HIV-1

human immunodeficiency virus type 1

- sCD4

soluble CD4

- gp120

120 kDa glycoprotein

- gp41

41 kDa glycoprotein

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- CD4bs

CD4 binding site

- CD4i

CD4 induced epitope

- CDR

complimentarity determining region

- PBS

phosphate–buffered saline

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute of Health grant P01 GM 56550 and CHAVI U19AI067854-04.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

(1) Fab X5 and Fc M9 enhancement of gp120 binding to sCD4 and inhibition of gp120 binding to 17b. (2) Characterization of gp120 binding to CG10. (3) Sensorgram profiles for gp120 binding to sCD4, b12 and 17b. (4) Characterization of [F5W]CD4F23 binding to gp120, competition with sCD4 and enhancement of 17b binding. (5) Kinetic values for gp120 binding to ligands of HIV-1 and the theoretical affinity and thermodynamic values for these interactions with the gp120-m18 complex. (6) Direct binding kinetics for HIV-1YU-2 gp120 wild type and mutant proteins to sCD4, IgG b12, IgG 17b and Fab m18 as determined by SPR analysis. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Helseth E, Olshevsky U, Furman C, Sodroski J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein regions important for association with the gp41 transmembrane glycoprotein. J Virol. 1991;65:2119–2123. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.2119-2123.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang X, Kurteva S, Ren X, Lee S, Sodroski J. Stoichiometry of envelope glycoprotein trimers in the entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2005;79:12132–12147. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12132-12147.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu P, Chertova E, Bess J, Jr, Lifson JD, Arthur LO, Liu J, Taylor KA, Roux KH. Electron tomography analysis of envelope glycoprotein trimers on HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus virions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15812–15817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2634931100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu P, Liu J, Bess J, Jr, Chertova E, Lifson JD, Grise H, Ofek GA, Taylor KA, Roux KH. Distribution and three-dimensional structure of AIDS virus envelope spikes. Nature. 2006;441:847–852. doi: 10.1038/nature04817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng Y, Broder CC, Kennedy PE, Berger EA. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu L, Gerard NP, Wyatt R, Choe H, Parolin C, Ruffing N, Borsetti A, Cardoso AA, Desjardin E, Newman W, Gerard C, Sodroski J. CD4-induced interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins with the chemokine receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:179–183. doi: 10.1038/384179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lusso P. HIV and the chemokine system: 10 years later. Embo J. 2006;25:447–456. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oppermann M. Chemokine receptor CCR5: insights into structure, function, and regulation. Cell Signal. 2004;16:1201–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trkola A, Dragic T, Arthos J, Binley JM, Olson WC, Allaway GP, Cheng_Mayer C, Robinson J, Maddon PJ, Moore JP. CD4-dependent, antibody-sensitive interactions between HIV-1 and its coreceptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:184–187. doi: 10.1038/384184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myszka DG, Sweet RW, Hensley P, Brigham_Burke M, Kwong PD, Hendrickson WA, Wyatt R, Sodroski J, Doyle ML. Energetics of the HIV gp120-CD4 binding reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9026–9031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison SC, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature. 1997;387:426–430. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rits-Volloch S, Frey G, Harrison SC, Chen B. Restraining the conformation of HIV-1 gp120 by removing a flexible loop. Embo J. 2006;25:5026–5035. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizzuto CD, Wyatt R, Hernandez-Ramos N, Sun Y, Kwong PD, Hendrickson WA, Sodroski J. A conserved HIV gp120 glycoprotein structure involved in chemokine receptor binding. Science. 1998;280:1949–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salzwedel K, Smith ED, Dey B, Berger EA. Sequential CD4-coreceptor interactions in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env function: soluble CD4 activates Env for coreceptor-dependent fusion and reveals blocking activities of antibodies against cryptic conserved epitopes on gp120. J Virol. 2000;74:326–333. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.326-333.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan N, Sun Y, Sattentau Q, Thali M, Wu D, Denisova G, Gershoni J, Robinson J, Moore J, Sodroski J. CD4-Induced conformational changes in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 glycoprotein: consequences for virus entry and neutralization. J Virol. 1998;72:4694–4703. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4694-4703.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raja A, Venturi M, Kwong P, Sodroski J. CD4 binding site antibodies inhibit human immunodeficiency virus gp120 envelope glycoprotein interaction with CCR5. J Virol. 2003;77:713–718. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.713-718.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pohlmann S, Reeves JD. Cellular entry of HIV: Evaluation of therapeutic targets. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:1963–1973. doi: 10.2174/138161206777442155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leonard JT, Roy K. The HIV entry inhibitors revisited. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:911–934. doi: 10.2174/092986706776361030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierson TC, Doms RW. HIV-1 entry and its inhibition. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2003;281:1–27. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-19012-4_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong XN, Xiao Y, Dierich MP, Chen YH. N- and C-domains of HIV-1 gp41: mutation, structure and functions. Immunol Lett. 2001;75:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(00)00302-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sattentau QJ, Moore JP, Vignaux F, Traincard F, Poignard P. Conformational changes induced in the envelope glycoproteins of the human and simian immunodeficiency viruses by soluble receptor binding. J Virol. 1993;67:7383–7393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7383-7393.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sattentau QJ, Moore JP. Conformational changes induced in the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein by soluble CD4 binding. J Exp Med. 1991;174:407–415. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallo SA, Puri A, Blumenthal R. HIV-1 gp41 six-helix bundle formation occurs rapidly after the engagement of gp120 by CXCR4 in the HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion process. Biochemistry. 2001;40:12231–12236. doi: 10.1021/bi0155596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sattentau QJ. CD4 activation of HIV fusion. Int J Cell Cloning. 1992;10:323–332. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530100603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Briz V, Poveda E, Soriano V. HIV entry inhibitors: mechanisms of action and resistance pathways. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:619–627. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young TP. Immune mechanisms in HIV infection. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2003;14:71–75. doi: 10.1177/1055329003259054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan W, Bazick J, Sodroski J. Characterization of the multiple conformational States of free monomeric and trimeric human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoproteins after fixation by cross-linker. J Virol. 2006;80:6725–6737. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00118-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore PL, Crooks ET, Porter L, Zhu P, Cayanan CS, Grise H, Corcoran P, Zwick MB, Franti M, Morris L, Roux KH, Burton DR, Binley JM. Nature of nonfunctional envelope proteins on the surface of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2006;80:2515–2528. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2515-2528.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwong PD, Doyle ML, Casper DJ, Cicala C, Leavitt SA, Majeed S, Steenbeke TD, Venturi M, Chaiken I, Fung M, Katinger H, Parren PW, Robinson J, Van Ryk D, Wang L, Burton DR, Freire E, Wyatt R, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA, Arthos J. HIV-1 evades antibody-mediated neutralization through conformational masking of receptor-binding sites. Nature. 2002;420:678–682. doi: 10.1038/nature01188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyatt R, Kwong PD, Desjardins E, Sweet RW, Robinson J, Hendrickson WA, Sodroski JG. The antigenic structure of the HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature. 1998;393:705–711. doi: 10.1038/31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wyatt R, Sodroski J. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science. 1998;280:1884–1888. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muster T, Steindl F, Purtscher M, Trkola A, Klima A, Himmler G, Ruker F, Katinger H. A conserved neutralizing epitope on gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1993;67:6642–6647. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6642-6647.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zwick MB, Jensen R, Church S, Wang M, Stiegler G, Kunert R, Katinger H, Burton DR. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 require surprisingly few crucial residues in the membrane-proximal external region of glycoprotein gp41 to neutralize HIV-1. J Virol. 2005;79:1252–1261. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1252-1261.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brunel FM, Zwick MB, Cardoso RM, Nelson JD, Wilson IA, Burton DR, Dawson PE. Structure-function analysis of the epitope for 4E10, a broadly neutralizing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody. J Virol. 2006;80:1680–1687. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1680-1687.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou T, Xu L, Dey B, Hessell AJ, Van Ryk D, Xiang SH, Yang X, Zhang MY, Zwick MB, Arthos J, Burton DR, Dimitrov DS, Sodroski J, Wyatt R, Nabel GJ, Kwong PD. Structural definition of a conserved neutralization epitope on HIV-1 gp120. Nature. 2007;445:732–737. doi: 10.1038/nature05580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkinson RA, Piscitelli C, Teintze M, Cavacini LA, Posner MR, Lawrence CM. Structure of the Fab fragment of F105, a broadly reactive anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody that recognizes the CD4 binding site of HIV type 1 gp120. J Virol. 2005;79:13060–13069. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.20.13060-13069.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen L, Do Kwon Y, Zhou T, Wu X, O’Dell S, Cavacini L, Hessell AJ, Pancera M, Tang M, Xu L, Yang ZY, Zhang MY, Arthos J, Burton DR, Dimitrov DS, Nabel GJ, Posner MR, Sodroski J, Wyatt R, Mascola JR, Kwong PD. Structural basis of immune evasion at the site of CD4 attachment on HIV-1 gp120. Science. 2009;326:1123–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.1175868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanders RW, Venturi M, Schiffner L, Kalyanaraman R, Katinger H, Lloyd KO, Kwong PD, Moore JP. The mannose-dependent epitope for neutralizing antibody 2G12 on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp120. J Virol. 2002;76:7293–7305. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.7293-7305.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scanlan CN, Pantophlet R, Wormald MR, Ollmann Saphire E, Stanfield R, Wilson IA, Katinger H, Dwek RA, Rudd PM, Burton DR. The broadly neutralizing anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2G12 recognizes a cluster of alpha1-->2 mannose residues on the outer face of gp120. J Virol. 2002;76:7306–7321. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.7306-7321.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trkola A, Purtscher M, Muster T, Ballaun C, Buchacher A, Sullivan N, Srinivasan K, Sodroski J, Moore JP, Katinger H. Human monoclonal antibody 2G12 defines a distinctive neutralization epitope on the gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1996;70:1100–1108. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1100-1108.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Binley JM, Wrin T, Korber B, Zwick MB, Wang M, Chappey C, Stiegler G, Kunert R, Zolla-Pazner S, Katinger H, Petropoulos CJ, Burton DR. Comprehensive cross-clade neutralization analysis of a panel of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 2004;78:13232–13252. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13232-13252.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Binley JM, Ngo-Abdalla S, Moore P, Bobardt M, Chatterji U, Gallay P, Burton DR, Wilson IA, Elder JH, de Parseval A. Inhibition of HIV Env binding to cellular receptors by monoclonal antibody 2G12 as probed by Fc-tagged gp120. Retrovirology. 2006;3:39. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu X, Yang ZY, Li Y, Hogerkorp CM, Schief WR, Seaman MS, Zhou T, Schmidt SD, Wu L, Xu L, Longo NS, McKee K, O’Dell S, Louder MK, Wycuff DL, Feng Y, Nason M, Doria-Rose N, Connors M, Kwong PD, Roederer M, Wyatt RT, Nabel GJ, Mascola JR. Rational design of envelope identifies broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to HIV-1. Science. 2010;329:856–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1187659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou T, Georgiev I, Wu X, Yang ZY, Dai K, Finzi A, Kwon YD, Scheid JF, Shi W, Xu L, Yang Y, Zhu J, Nussenzweig MC, Sodroski J, Shapiro L, Nabel GJ, Mascola JR, Kwong PD. Structural basis for broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 by antibody VRC01. Science. 2010;329:811–817. doi: 10.1126/science.1192819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doores KJ, Burton DR. Variable loop glycan dependency of the broad and potent HIV-1-neutralizing antibodies PG9 and PG16. J Virol. 2010;84:10510–10521. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00552-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pancera M, McLellan JS, Wu X, Zhu J, Changela A, Schmidt SD, Yang Y, Zhou T, Phogat S, Mascola JR, Kwong PD. Crystal structure of PG16 and chimeric dissection with somatically related PG9: structure-function analysis of two quaternary-specific antibodies that effectively neutralize HIV-1. J Virol. 2010;84:8098–8110. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00966-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pejchal R, Walker LM, Stanfield RL, Phogat SK, Koff WC, Poignard P, Burton DR, Wilson IA. Structure and function of broadly reactive antibody PG16 reveal an H3 subdomain that mediates potent neutralization of HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11483–11488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004600107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang MY, Shu Y, Phogat S, Xiao X, Cham F, Bouma P, Choudhary A, Feng YR, Sanz I, Rybak S, Broder CC, Quinnan GV, Evans T, Dimitrov DS. Broadly cross-reactive HIV neutralizing human monoclonal antibody Fab selected by sequential antigen panning of a phage display library. J Immunol Methods. 2003;283:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bessette PH, Rice JJ, Daugherty PS. Rapid isolation of high-affinity protein binding peptides using bacterial display. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2004;17:731–739. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzh084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prabakaran P, Gan J, Wu YQ, Zhang MY, Dimitrov DS, Ji X. Structural mimicry of CD4 by a cross-reactive HIV-1 neutralizing antibody with CDR-H2 and H3 containing unique motifs. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:82–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moore JP, Sodroski J. Antibody cross-competition analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 exterior envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1996;70:1863–1872. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1863-1872.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dowd CS, Leavitt S, Babcock G, Godillot AP, Van Ryk D, Canziani GA, Sodroski J, Freire E, Chaiken IM. Beta-turn Phe in HIV-1 Env binding site of CD4 and CD4 mimetic miniprotein enhances Env binding affinity but is not required for activation of coreceptor/17b site. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7038–7046. doi: 10.1021/bi012168i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Y, Migueles SA, Welcher B, Svehla K, Phogat A, Louder MK, Wu X, Shaw GM, Connors M, Wyatt RT, Mascola JR. Broad HIV-1 neutralization mediated by CD4-binding site antibodies. Nat Med. 2007;13:1032–1034. doi: 10.1038/nm1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roben P, Moore JP, Thali M, Sodroski J, Barbas CF, 3rd, Burton DR. Recognition properties of a panel of human recombinant Fab fragments to the CD4 binding site of gp120 that show differing abilities to neutralize human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:4821–4828. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4821-4828.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Binley JM, Lybarger EA, Crooks ET, Seaman MS, Gray E, Davis KL, Decker JM, Wycuff D, Harris L, Hawkins N, Wood B, Nathe C, Richman D, Tomaras GD, Bibollet-Ruche F, Robinson JE, Morris L, Shaw GM, Montefiori DC, Mascola JR. Profiling the specificity of neutralizing antibodies in a large panel of plasmas from patients chronically infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes B and C. J Virol. 2008;82:11651–11668. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01762-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olshevsky U, Helseth E, Furman C, Li J, Haseltine W, Sodroski J. Identification of individual human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 amino acids important for CD4 receptor binding. J Virol. 1990;64:5701–5707. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.5701-5707.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thali M, Moore JP, Furman C, Charles M, Ho DD, Robinson J, Sodroski J. Characterization of conserved human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 neutralization epitopes exposed upon gp120-CD4 binding. J Virol. 1993;67:3978–3988. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3978-3988.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xiang SH, Kwong PD, Gupta R, Rizzuto CD, Casper DJ, Wyatt R, Wang L, Hendrickson WA, Doyle ML, Sodroski J. Mutagenic stabilization and/or disruption of a CD4-bound state reveals distinct conformations of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Journal of Virology. 2002;76:9888–9899. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.19.9888-9899.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McFadden K, Cocklin S, Gopi H, Baxter S, Ajith S, Mahmood N, Shattock R, Chaiken I. A recombinant allosteric lectin antagonist of HIV-1 envelope gp120 interactions. Proteins. 2007;67:617–629. doi: 10.1002/prot.21295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang CC, Stricher F, Martin L, Decker JM, Majeed S, Barthe P, Hendrickson WA, Robinson J, Roumestand C, Sodroski J, Wyatt R, Shaw GM, Vita C, Kwong PD. Scorpion-toxin mimics of CD4 in complex with human immunodeficiency virus gp120 crystal structures, molecular mimicry, and neutralization breadth. Structure. 2005;13:755–768. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Biorn AC, Cocklin S, Madani N, Si Z, Ivanovic T, Samanen J, Van Ryk DI, Pantophlet R, Burton DR, Freire E, Sodroski J, Chaiken IM. Mode of action for linear peptide inhibitors of HIV-1 gp120 interactions. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1928–1938. doi: 10.1021/bi035088i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brower ET, Schon A, Klein JC, Freire E. Binding thermodynamics of the N-terminal peptide of the CCR5 coreceptor to HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. Biochemistry. 2009;48:779–785. doi: 10.1021/bi8021476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schon A, Madani N, Klein JC, Hubicki A, Ng D, Yang X, Smith AB, 3rd, Sodroski J, Freire E. Thermodynamics of Binding of a Low-Molecular-Weight CD4 Mimetic to HIV-1 gp120. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10973–10980. doi: 10.1021/bi061193r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Desjardins E, Robinson J, Culp JS, Hellmig BD, Sweet RW, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. Probability analysis of variational crystallization and its application to gp120, the exterior envelope glycoprotein of type 1 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4115–4123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet RW, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ames RS, Tornetta MA, McMillan LJ, Kaiser KF, Holmes SD, Appelbaum E, Cusimano DM, Theisen TW, Gross MS, Jones CS, et al. Neutralizing murine monoclonal antibodies to human IL-5 isolated from hybridomas and a filamentous phage Fab display library. J Immunol. 1995;154:6355–6364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Majeed S, Robinson J, Sweet RW, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. Structures of HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoproteins from laboratory-adapted and primary isolates. Structure Fold Des. 2000;8:1329–1339. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huang CC, Tang M, Zhang MY, Majeed S, Montabana E, Stanfield RL, Dimitrov DS, Korber B, Sodroski J, Wilson IA, Wyatt R, Kwong PD. Structure of a V3-containing HIV-1 gp120 core. Science. 2005;310:1025–1028. doi: 10.1126/science.1118398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huang CC, Lam SN, Acharya P, Tang M, Xiang SH, Hussan SS, Stanfield RL, Robinson J, Sodroski J, Wilson IA, Wyatt R, Bewley CA, Kwong PD. Structures of the CCR5 N terminus and of a tyrosine-sulfated antibody with HIV-1 gp120 and CD4. Science. 2007;317:1930–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1145373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee S, Peden K, Dimitrov DS, Broder CC, Manischewitz J, Denisova G, Gershoni JM, Golding H. Enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope-mediated fusion by a CD4-gp120 complex-specific monoclonal antibody. J Virol. 1997;71:6037–6043. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6037-6043.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meyuhas R, Noy H, Montefiori DC, Denisova G, Gershoni JM, Gross G. HIV-1 neutralization by chimeric CD4-CG10 polypeptides fused to human IgG1. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:1099–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dey B, Pancera M, Svehla K, Shu Y, Xiang SH, Vainshtein J, Li Y, Sodroski J, Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Wyatt R. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 monomeric and trimeric gp120 glycoproteins stabilized in the CD4-bound state: antigenicity, biophysics, and immunogenicity. J Virol. 2007;81:5579–5593. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02500-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu L, Zhou T, Yang ZY, Svehla K, O’Dell S, Louder MK, Xu L, Mascola JR, Burton DR, Hoxie JA, Doms RW, Kwong PD, Nabel GJ. Enhanced exposure of the CD4-binding site to neutralizing antibodies by structural design of a membrane-anchored human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 domain. J Virol. 2009;83:5077–5086. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02600-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Feldhahn N, Seaman MS, Velinzon K, Pietzsch J, Ott RG, Anthony RM, Zebroski H, Hurley A, Phogat A, Chakrabarti B, Li Y, Connors M, Pereyra F, Walker BD, Wardemann H, Ho D, Wyatt RT, Mascola JR, Ravetch JV, Nussenzweig MC. Broad diversity of neutralizing antibodies isolated from memory B cells in HIV-infected individuals. Nature. 2009;458:636–640. doi: 10.1038/nature07930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thali M, Olshevsky U, Furman C, Gabuzda D, Posner M, Sodroski J. Characterization of a discontinuous human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 epitope recognized by a broadly reactive neutralizing human monoclonal antibody. J Virol. 1991;65:6188–6193. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6188-6193.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]