Abstract

A variety of features of autism can be simulated in rodents, including the core behavioral hallmarks of stereotyped and repetitive behaviors, and deficits in social interaction and communication. Other behaviors frequently found in autism spectrum disorders (ASD) such as neophobia, enhanced anxiety, abnormal pain sensitivity and eye blink conditioning, disturbed sleep patterns, seizures, and deficits in sensorimotor gating are also present in some of the animal models. Neuropathology and some characteristic neurochemical changes that are frequently seen in autism, as well as alterations in the immune status in the brain and periphery are also found in some of the models. Several known environmental risk factors for autism have been successfully established in rodents, including maternal infection and maternal valproate administration. Also under investigation are a number of mouse models based on genetic variants associated with autism or on syndromic disorders with autistic features. This review briefly summarizes recent developments in this field, highlighting models with face and/or construct validity, and noting the potential for investigation of pathogenesis and early progress towards clinical testing of potential therapeutics. Wherever possible, reference is made to reviews rather than primary articles.

There are a number of difficulties in developing animal models with features of autism. First, the disorder is currently defined by a set of core behavioral abnormalities rather than by objective biomarkers. Moreover, two of the core features, deficits in social interaction and in communication, can only be approximated in rodent studies (1). Second, autism may actually represent a set of behaviorally distinct disorders, with different causes and divergent pathogenesis (2). Use of the broader definition, autism spectrum disorders (ASD), further compounds this problem. Third, the genetics of autism is complex, encompassing numerous candidate genes, copy number variations, and monogenic, syndromic disorders that display autistic symptoms (3). Fourth, there is currently no pathognomic feature of autism that can be assayed in animals that can be used clearly distinguish, for instance, an “autistic mouse” from a “schizophrenic mouse” (4). Despite these obstacles, animal research has progressed rapidly in recent years, and a subset of the numerous proposed models display many of the characteristic features of autism, at least as they can be assayed in animals.

Behaviors in mice and rats can be directly related to the three core symptoms of autism: (i) deficits in social interaction (e.g., 3 chamber assay or analysis of videotapes), (ii) deficits in communication (e.g., ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs) or scent marking), and (iii) increased repetitive/stereotyped motor behaviors (e.g., self grooming or marble burying), and insistence on sameness and restricted interests (e.g., neophobia, perseveration in the T maze or water maze) (1). Rodents can also be tested for a number of other behaviors found in subsets of ASD subjects such as enhanced anxiety and eye blink conditioning, and a deficit in sensorimotor gating (prepulse inhibition; PPI). A neuropathology characteristic of autism, a spatially-localized deficit in Purkinje cells, is also found in certain mouse models.

Environmental risk factors

Maternal infection

A very large epidemiological study utilizing the Danish Medical Register recently confirmed and strongly extended prior studies that suggested maternal infection as a risk factor for autism in the offspring. An examination of over 10,000 autism cases found a very significant association with maternal viral infection in the first trimester (5). Rodent models of this risk factor include maternal respiratory infection with influenza virus, and maternal immune activation (MIA) with either polyinosine:cytosine (poly(I:C)), a synthetic, double-stranded RNA that evokes an antiviral-like immune reaction, or lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which evokes an anti-bacterial-like immune reaction. The poly(I:C) MIA model has been extensively studied with regard to the behavior of the offspring, as well as their neuropathology, neurochemistry, structural MRI and, more recently electrophysiology (4, 6, 7). Depending on the gestational age at which MIA or infection is administered, these offspring can be studied in the context not only of autism, but also schizophrenia, as maternal infection is a well-characterized risk factor for the latter disorder as well (8). Poly(I:C) MIA offspring exhibit behaviors similar to the core symptoms of autism: deficits in social interaction and communication (ultrasonic vocalizations, USVs), as well as increased repetitive/stereotyped motor behaviors (self grooming and marble burying, and perseveration in the water maze) (4, 7, and unpublished data). These offspring also display a number of other behaviors found in subsets of ASD subjects such as neophobia, enhanced anxiety and eye blink conditioning, and a deficit in PPI (4, 6, and unpublished data). A characteristic autism neuropathology, spatially-localized deficit in Purkinje cells, is also present in the offspring of infected mothers (9), and poly(I:C)-induced MIA causes other histopathological changes similar to those seen in autism (4, 6, 10, 11). At the same time, features characteristic of schizophrenia are also present: enlarged ventricles, alterations in dopaminergic neurochemistry, and some of the behavioral abnormalities are post-pubertal in onset and are ameliorated by anti-psychotic drugs (4, 6). Recent electrophysiological studies have revealed synaptic changes within the hippocampus and in its communication with the prefrontal cortex (12–14).

Maternal LPS administration yields offspring with some of the same features, and a few of the abnormal behaviors can be reversed by anti-psychotic drug treatment (4). Neuropathology in the LPS model ranges from severe to very mild, depending on the treatment protocol (4, 7, 15). Some of these effects, such as increased cell density and limited dendritic arbors in the hippocampus, have been found in autism. Electrophysiological recordings reveal reduced synaptic input to CA1 of the hippocampus, heightened excitability of pyramidal neurons, enhanced postsynaptic glutamatergic responses, and impaired NMDA-induced synaptic plasticity (4, 16, 17).

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that the maternal infection and MIA models display face (similar symptoms) as well as construct (similar cause) value for both autism and schizophrenia. These models may have predictive value as well. Several types of perturbation can ameliorate the adverse effects of MIA on the offspring. For instance, pretreatment of pregnant rats with N-acetyl-cysteine, which increases calcium influx when binding to glutamate receptors in combination with the transmitter, and also suppresses fetal inflammatory responses to LPS, prevents many of the effects of maternal LPS (17–19). Changing the balance of cytokines can also block MIA effects. A single injection of IL-6 in pregnant mice induces many of the behavioral abnormalities in the offspring seen with poly(I:C) injection. Conversely, injection of the mother with an anti-IL-6 antibody blocks the effects of poly(I:C), and poly(I:C) injection in IL-6 knockout (KO) mothers yields normal offspring (20). Moreover, the elevation in maternal IL-6 causes an inflammatory imbalance in the placenta, which leads to endocrine changes that are likely to be detrimental to the fetus (21) (Figs. 1–2). There is also severe placental inflammation when pregnant rats are given a high dose of LPS, and this reaction can be blocked by administration of an IL-1 receptor antagonist (22). Administration of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 prevents fetal loss and white matter damage following uterine bacterial infection. Elevation of IL-10 also has a protective effect in pregnant mice given LPS or poly(I:C)(4). An attractive feature of this potential therapeutic is that endogenous IL-10 is essential for resistance to LPS-induced preterm labor and fetal loss. Thus, administration of this cytokine enhances the natural protective mechanism. However, increased IL-10 in the absence of MIA in pregnant mice can lead to behavioral abnormalities in the adult offspring (23), a finding likely related to the fact that normal human pregnancy involves increased inflammation (24, 25).

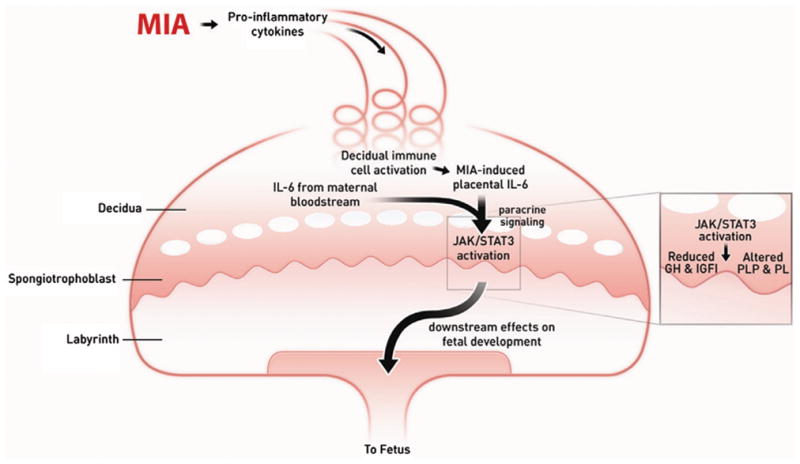

Figure 1. Summary of MIA-induced effects on the placenta.

Maternal injection of poly(I:C) activates the maternal immune system, elevating pro-inflammatory factors, including IL-6, which enters the spiral arteries that descend through the decidua and spongiotrophoblast layers, filling the maternal bloodspaces of the labyrinth. Resident immune cells in the decidua are activated to express CD69 and further propagate the inflammatory response. IL-6 derived from decidual cells acts in a paracrine manner on target cells in the spongiotrophoblast layer. Ligation with the cognate receptor IL-6Ra with gp130 leads to JAK/STAT3 activation and increases in acute phase proteins, such as SOCS3, and downregulation of placental growth hormone (GH) production. This leads to reduced insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 (IGFBP3) and IGFI. Global changes in STAT3 activation in the spongiotrophoblast layer alters the production of placenta-specific pro-lactin protein (PLP) and other pro-lactin proteins. These changes in endocrine factors are very likely to lead to acute placental pathophysiology and subsequent effects on fetal development. Reprinted from Hsiao EY, Patterson PH Brain Behav Immun doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2010.12.017; Copyright © 2010 Elsevier, Ltd. with permission.

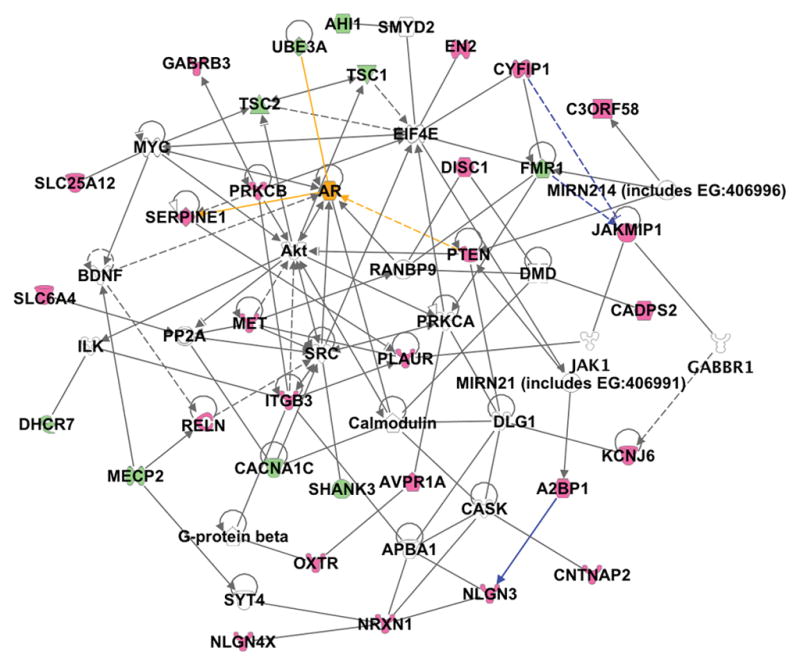

Figure 2. A social network for autism susceptibility candidate genes.

Analysis of the relationships between 33 autism candidate genes (red emblems) and associated syndrome genes (green emblems) was carried out using the Ingenuity pathway analysis. Direct (solid lines) and indirect (dashed lines) associations between the candidate genes demonstrate the close relationships between these genes. Recently published interactions linking FMR1, CYFIP1, and JAKMIP1 by gene regulation, and A2BP1 (FOX1) with NLGN3 by splicing regulation were added as custom interactions (blue lines). The androgen receptor (orange emblem) and three of its interactions with candidate genes (orange lines) are highlighted to demonstrate the correlation with the extreme male brain hypothesis. (Reprinted from Bill BR and Geschwind DH Curr Opin Genetics Devel 19:271–278; Copyright © 2010 Elsevier, Ltd. with permission)

Postnatal cytokine perturbations are a safer potential therapeutic approach. A preliminary study of the thiazolidinedione, pioglitazone, which has anti-inflammatory properties, causes a significant decrease in irritability, lethargy, stereotypy and hyperactivity in autistic children, with greater effects on younger patients (26). MIA models provide an attractive platform for further testing of such therapies. It is also clear that postnatal cytokine manipulations can induce behavioral changes in the absence of MIA (27).

Valproic acid

Another model with construct and face validity involves maternal valproic acid (VPA; valproate) administration. The offspring of women taking this medication for mental illness or epilepsy during early pregnancy are at elevated risk for autism (7, 28, 29). In pregnant rats, a single injection of VPA results in behavioral abnormalities such as increased stereotypic/repetitive behavior, decreased social interaction, altered sensitivity to sensory stimuli, impaired PPI, elevated anxiety, impaired reversal learning, altered eye blink conditioning, and enhanced fear memory processing, all of which are consistent with autism, and are also found in MIA offspring (4, 29). It is interesting that maternal VPA exposure leads to reduced expression of neuroligin (30), an autism candidate gene that is described below. Electrophysiological studies indicate that VPA offspring exhibit abnormal microcircuit connectivity (31), which may be related to MRI studies showing impaired long-range functional connectivity in autism. Recordings in the lateral amygdaloid nucleus suggest molecular and synaptic alterations in VPA mice that are relevant for the alterations in amygdala morphology and behavior in autism (32). There are also immune abnormalities such as decreased weight of the thymus, decreased splenocyte response to stimulation and a lower IFNγ/IL-10 ratio. Most of these abnormalities are found only in male offspring, which is consistent with the male bias in autism incidence (29).

The key mechanism(s) underlying the effects of maternal VPA on fetal brain development are unclear at present, primarily because this molecule has a wide range of activities, including altering gene expression, cell death and immune dysregulation.

Although maternal VPA exposure is responsible for only a tiny fraction of autism cases, this syndrome, together with the maternal infection risk factor, provides abundant proof-of-principle for environmental influences on autism incidence. Moreover, the similarities in neuropathology and behavior between the rodent models and human autism support the utility of environment-based models for defining relevant pathways of developmental dysregulation. A next step is to test the gene-environment paradigm by asking if the effects of maternal VPA or MIA can be exacerbated in mice carrying genetic variants associated with increased risk for autism. In one interesting experiment, such offspring were raised under conditions of environmental enrichment (EE), in which rodents are reared in groups in relatively large enclosures, with a wide variety of objects to explore, as well as running wheels on which to exercise. Compared to VPA offspring raised under standard housing conditions, treating VPA offspring for just one week with EE results in significant improvements in anxiety, stereotyped behaviors, social interaction and PPI (33). It is striking that in this experiment, the therapeutic effects of EE administered during the rat equivalent of childhood were able to last through adulthood.

Genetic models

A number of different types of genetic modifications can increase the risk for developing ASD or autistic symptoms. Monogenic syndromes can involve core autistic symptoms as well as a variety of other serious conditions (tumors, physical malformations, etc.) that are not found in ASD. There are also several very rare Mendelian mutations, as well as de novo chromosomal deletions or duplications (copy number variations; CNVs) that cause ASD. Many of these mutations and CNVs cause a broader phenotype than that found in idiopathic autism. There are a great many mouse models for this diverse array of genetic variants and, given space limitations, only a few can be described briefly here.

FMR1

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is caused by mutations in the FMR1 gene on the X chromosome. The disorder shares a number of symptoms in common with autism, mental retardation, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and epilepsy. Fmr1 KO mice display some core behavioral features of autism including impaired social interaction and repetitive behavior. Expression of other autism-related symptoms such as anxiety and hyperactivity depends on the genetic background (34). A 50% reduction of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR-5) expression in these mice normalizes dendrite morphology, seizure susceptibility, and inhibitory avoidance extinction. The mGluR theory of FXS proposes that upregulation of group I mGluR causes exaggerated protein synthesis-dependent functions, which underlie the neuropathology and behavioral traits associated with FXS (35).

FXS appears to be one of several ASD-related disorders that exhibit an imbalance between excitation and inhibition in brain circuitry. In the case of FXS, experiments in an Fmr1 KO model indicate that there is too much excitation, which leads to deficits in cognitive function. In a Drosophila model, lowering the level of excitation with a drug that inhibits binding of a common excitatory neurotransmitter to its receptor rescues memory deficits and defective courtship behavior as well as structural abnormalities in the central nervous system. The ability to rescue some of the behaviors by treatment in the adult suggests that rectifying the excitatory/inhibitory imbalance is enough for restoration of function even with possible defects in the wiring patterns caused during development. Moreover, a similar pharmacological treatment in the adult mouse KO reverses anxiety in the open field and susceptibility to seizures (36). These results formed the basis of small, open label clinical trials using medications that have effects similar to those tested in the mice. These trials yielded positive results, improving a variety of deficits in the patients, and still unpublished results from one double blind trial are said to be positive. Clinical trials are also underway to test two other types of medications, unrelated to the excitatory/inhibitory balance, but which work well in FXS animal models (36).

MeCP2

Rett syndrome (RTT) is another genetic disorder that displays a wide variety of symptoms, some of which resemble those found in autism. The patients, which are almost entirely females, appear to develop normally for 6–18 months, but this is followed by ASD symptom onset, severe mental retardation, seizures and features highly characteristic of RTT such as stereotyped hand movements, abnormal breathing, motor deficits and scoliosis. The mutations causing the disease are in the gene, methyl-CpG-binding protein (MeCP2). In the female mouse model of MeCP2 disruption, the mice appear normal until about 16 weeks of age (a mouse typically is mature by 4 weeks and dies at 2–3 years). Behavioral deficits in these mice include enhanced anxiety in the open field, reduced nest-building, and aberrant social interactions. Genetic background modifies learning and memory performance (37). Mice over-expressing MeCP2 also develop a progressive neurological disorder with, surprisingly, an enhancement in synaptic plasticity, motor and contextual learning skills between age 10 and 20 weeks, and, at an older age, hypoactivity, seizures, and abnormal forelimb-clasping, all of which are reminiscent of human Rett syndrome (37). While this time course certainly indicates a regression, it does not resemble the time course of the regressive form of autism or of RTT.

Remarkably, restoring MeCP2 expression in a conditional KO model in immature or even in mature mice results in reversal of the disease phenotype, as measured by behavioral and electrophysiological tests (38). Thus, despite the fact that MeCP2 function was disrupted during fetal and postnatal development, several disease symptoms can be reversed. In a test of a potential treatment based on a growth factor deficiency observed in RTT, administration of an active peptide fragment of insulin-like growth factor 1 to MeCP2 mutant mice extends life span, improves locomotor, heart and breathing functions, and stabilizes a measure of cortical plasticity (38). Synaptic dysfunction can also be achieved by increasing the level of another growth factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor(39). A clinical trial testing IGF-1 in RTT patients began in 2009. Still another intriguing approach for RTT is EE, which improves several aspects of the disease phenotype. Moreover, levels of brain brain-derived neurotrophic factor and IGF-1 are increased by EE (40). While EE does not restore normal behavior or lifespan to the RTT mice, it does induce some significant positive effects.

TSC

Tuberous sclerosis (TSC) is a genetic disease with ASD symptoms in which mutations in one of two TSC genes cause multiple, benign tumors to grow in various tissues including the brain. Hamartin and tuberin, the protein products of TSC1 and TSC2, inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (41). Interestingly, mTOR signaling is dysregulated in the FMRP-deficient mouse (42). In addition, as in MeCP2 mutant mice, the Tsc2+/− KO mouse model responds to treatment in adulthood. Brief administration of the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin rescues synaptic plasticity and the behavioral deficits in the TSC model (43). Moreover, early phase clinical trials suggest that cognitive features of TSC may be reversible in adult humans (44).

Although it is thought that autism can result from an environmental stimulus acting on a susceptible genetic background, there has little has been published on this issue thus far. Thus, it is important that Tsc2+/− mice display a social interaction deficit only when they are born to mothers treated with poly(I:C) (45). That is, this deficit is most severe when the MIA environmental risk factor is combined with a genetic defect that, in humans, also carries a high risk for ASD. In addition, there is an excess of TSC-ASD individuals born during the peak influenza season, an association that is not seen for TSC individuals not displaying ASD symptoms (45).

NLGN3 and 4

Several rare, causal variants in the neuroligin (NLGN)-3 and -4 genes are associated with ASD (46). These postsynaptic proteins, which, together with their presynaptic and intracellular binding partners, the β-neurexins and SHANK3, respectively, are involved in synaptic maturation and transmission. One missense mutation in NLGN-3 and four missense and two nonsense mutations in NLGN-4 have been identified in a very small number of individuals with ASDs (46), supporting the hypothesis that synaptic dysfunction is important in ASDs. Mutations in neurexin and SHANK3 are also found in ASD probands, but whether they are involved in ASD etiology is controversial (47). The KO for Shank1, the closest relative to Shank3, exhibits increased anxiety, impaired contextual fear memory and, surprisingly, enhanced performance in a spatial learning task but impaired memory retention of that task (48). Additional behavioral results relevant to the core autism symptoms have yet to be reported.

Results with NLGN-3 and -4 mutant mice support the functional significance of NLGNs in synaptic function and social behavior. A NLGN-3 knockin (KI) mouse with a point mutation in the endogenous mouse gene that is identical to the relevant human NLGN3 gene (49) displays increased inhibitory synaptic transmission without a change in excitatory transmission, a phenotype not observed in NLGN-3 KO mice, emphasizing the disparity between missense and nonsense mutations. The enhanced inhibitory synaptic transmission in NLGN-3 knockin mice is accompanied by a deficit in social interaction and, as observed in the Shank1 KO, enhanced spatial learning ability. These results are surprising because individuals with mutations in NLGN-3 and -4 do not exhibit potentiated learning skills. It is of potential therapeutic interest that administration of the NMDA receptor partial co-agonist (and anti-inflammatory agent) D-cycloserine can rescue the excessive grooming behavior in adult NLGN-1 KO mice (50).

Although NLGN-4 KO mice display abnormalities in two of the three core autistic symptoms, reciprocal social interaction and impaired USV communication, they do not appear to display repetitive behavior or impairments in some of the other autism symptoms such as sensory sensitivity, sensorimotor gating, locomotion, exploratory activity, anxiety, or learning and memory (51). These observations are consistent with those seen in patients with the NLGN-4 mutation, who also do not show these comorbid features. To summarize, several NLGN models exhibit strong construct validity, and the face validity of the NLGN-4 KO is fairly good at the behavioral level, but much remains to be done on its neuropathology.

CNTNAP2

A well-validated ASD susceptibility gene is contactin associated protein-like 2 (CNTNAP2), which is a member of the neuronal neurexin superfamily that is involved in neuron-glial interactions and is likely to be important in brain development (52). It is intriguing that CNTNP2 expression is elevated in circuits in the human cortex that are important for language development. Moreover, its expression is elevated in song nuclei required for vocal learning in the zebra finch, and this is male-specific, as is the song behavior (53). In addition, CNTNP2 polymorphisms are associated with language disorders, and the expression of this gene can be regulated by FOXP2, mutations in which can cause language and speech disorders (54). In light of these associations, it is important that the Cntnap2 KO mouse has a deficit in USVs and social interaction, and displays repetitive behaviors. These mice also exhibit several other features of ASD: seizures, mild cortical laminar disorganization and hyperactivity (unpublished data).

OT and AVP

Pharmacological and genetic manipulations of oxytocin (OT) and vasopressin (AVP) have unequivocally established the importance of these neuropeptides in the regulation of complex social behaviors. Moreover, functional alterations in these systems may contribute not only to social deficits in autism but also to repetitive behaviors (55, 56). For instance, reduced oxytocin (OT) plasma levels are observed in autistic children, and OT receptor mRNA is decreased in post-mortem autism temporal cortex. Conversely, intranasal infusion of OT reduces stereotypic behavior and improves eye contact and social memory in high functioning autistic patients. Moreover, genetic variations in OT receptor and AVP receptor V1aR can be associated with autism.

The face value of the OT and AVP KO mice for studying features of autism mixed, however. Adult OT KO mice display reduced anxiety, a finding inconsistent with autism. In addition, compared to WT, both OT and OT receptor (OTR) KO males emit fewer USVs in the pup isolation test, which is suggestive of decreased anxiety during maternal separation, but is also consistent with the lack of communication in ASD. The OT KO mice fail to recognize familiar conspecifics upon repeated social encounters, although olfactory and nonsocial memory are intact (1, 55, 56). This has been interpreted as an autism-like social deficit, although social amnesia has not been described in autism. Comprehensive neuropathology remains to be reported in these strains. Given the implications for ASD in the human findings, further study of OT mutant mice is warranted, although striking species differences are apparent for OT and AVP, and their receptors (55).

Male V1aR KO mice exhibit deficits in olfactory social recognition and social interaction (1, 55). Similar to OT and OTR KO mice, V1aR KO mice show reduced anxiety-like behavior. No deficits in learning and memory or in PPI are detected. V1bR KO adult females emit fewer USVs in a resident-intruder test. Although the number of USVs emitted by infant mutants is not affected during the conventional pup separation test, mutant pups fail to display maternal potentiation of USVs, which could suggest either a defect in a cognitive component or reduced anxiety (1). Thus, as for OT mice, the face value of AVPR KO mice is mixed.

BTBR

The BTBR mouse strain has been studied carefully at the behavioral level, and also displays a striking neuroanatomical feature. Compared to several other mouse strains, BTBR mice exhibit low levels of sociability, as well as abnormal social learning in the transmission of food preference test. Moreover, BTBR mice show a high level of spontaneous repetitive grooming, poor shift performance in a hole-board task, and a deficit in the water maze reversal task, which can be interpreted as the resistance to change in routine that is observed in autism (1, 57). BTBR pups emit more and longer USVs in comparison to C57 pups. Their repertoire of vocalization is also narrower in comparison to pups from standard mouse strains. However, one might expect to see lower rates of USVs in pups if modeling the ASD communication deficit. Such a deficit is reported in adult BTBR mice (1). Detailed study of the fine structure of USVs, as well as their behavioral functions in young and adult mice, is an important area for future studies of animal models of psychiatric disease.

Compared to C57 mice, BTBR mice display an exaggerated response to stress that is associated with high blood levels of corticosterone (58). Such enhanced stress could cause or aggravate the behavioral phenotype of these mice. Key anatomical features of BTBR mice are the absence of the corpus callosum and a reduced hippocampal commissure (1). Overall, a number of BTBR behaviors are consistent with autism, and the most striking anatomical feature in this strain is consistent with many, but not all, studies of the corpus callosum in autism (59).

A difficulty with this line is that comparisons are necessarily made to other, unrelated mouse lines, and it is not clear to which line(s) BTBR should be compared. For instance, similar to BTBR mice, but unlike C57 mice, BALB/c mice display low social behavior, reduced USVs and reduced empathy-like behavior (1). Because there are many genetic differences between such strains, comparing their behaviors is not equivalent to comparing behaviors and neuropathology between mutant and WT mice of the same genetic background. Nonetheless, the search for the genes causing behavioral phenotypes is ongoing, and a single nucleotide polymorphism in Kmo, which encodes kynurenine 3-hydroxylase, has been found in BTBR mice when compared to unrelated strains (1). This enzyme regulates the synthesis of kynurenic acid, a neuroprotective molecule whose levels are abnormal in other neuropsychiatric diseases, including schizophrenia.

Perspectives

Several of the genetic models, and both types of environmental risk factor models discussed here display some or all of the core behavioral features of autism. In general, the analysis of neuropathology and electrophysiology is at a more advanced stage in the environmental models. Much remains to be done regarding the immune status of the models, as well as the state of the gastrointestinal tract, which can be disturbed in ASD (60, 61, and unpublished data). The animal work has not yet shed light on the mysterious strong male bias found in autism prevalence. Much remains to be done to characterize the types and social functions of USVs in the rodents. Approaches towards understanding the Theory of Mind deficit in autism using rodents are just beginning, using assays for empathy (1), for instance. Another frontier is represented by intriguing non-human primate models based on immune manipulation and maternal infection (62, 63).

Acknowledgments

Autism-related research in the author’s laboratory is currently supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH079299, EUREKA MH086781, ARRA MH088879, P50 MH086383), and the Binational Science, International Rett Syndrome, Simons, and Autism Speaks Foundations.

Abbreviations

- ASD

autism spectrum disorders

- CNTNAP2

contactin associated protein-like 2

- EE

environmental enrichment

- FXS

Fragile X syndrome

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MeCP2

methyl CpG binding protein

- MIA

maternal immune activation

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- NLGN

neuroligin

- OT

oxytocin

- poly(I:C)

polyinosine:cytosine

- PPI

prepulse inhibition

- RTT

Rett syndrome

- TSC

tuberous sclerosis

- USV

ultrasonic vocalization

- VPA

valproic acid

References

- 1.Silverman JL, Yong M, Lord C, Crawley JN. Behavioral phenotyping assays for mouse models of autism. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:490–502. doi: 10.1038/nrn2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Constantino JN. The quantitative nature of autistic social impairment. Pediatr Res. 2011;69:XXX–XXX. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318212ec6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrahams BS, Geschwind DH. Connecting genes to brain in the autism spectrum disorders. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:395–399. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patterson PH. Immune involvement in schizophrenia and autism: Etiology, pathology and animal models. Behav Brain Res. 2009;204:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atladóttir HO, Thorsen P, Østergaard L, Schendel DE, Lemcke S, Abdallah M, Parner ET. Maternal infection requiring hospitalization during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:1423–1430. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1006-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dammann O, Meyer U. Schizophrenia and autism: both shared and disorder-specific pathogenesis via perinatal inflammation? Pediatr Res. 2011;69:XXX–XXX. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318212c196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsiao EY, Bregere C, Malkova N, Patterson PH. Modeling features of autism in rodents. In: Amaral DG, Dawson G, Geschwind DH, editors. Autism Spectrum Disorders. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2011. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown AS, Derkits EJ. Prenatal infection and schizophrenia: A review of epidemiologic and translational studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:261–280. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi L, Smith SE, Malkova N, Tse D, Su Y, Patterson PH. Activation of the maternal immune system alters cerebellar development in the offspring. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmitz C, van Kooten IA, Hof PR, van Engeland H, Patterson PH, Steinbusch HW. Autism: neuropathologylaterations of the GABAergic system, and animal models. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2005;71:1–26. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(05)71001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Miranda J, Yaddanpudi K, Hornig M, Villar G, Serge R, Lipkin WI. Induction of Toll-like receptor 3-mediated immunity during gestation inhibits cortical neurogenesis and causes behavioral disturbances. mBio. 2010;1:e00176–10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00176-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito HT, Smith SE, Hsiao E, Patterson PH. Maternal immune activation alters nonspatial information processing in the hippocampus of the adult offspring. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:930–941. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickerson DD, Wolff AR, Bilkey DK. Abnormal long-range neural synchrony in a maternal immune activation animal model of schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12424–12431. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3046-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oh-Nishi A, Obayashi S, Sugihara I, Suhara T. Maternal immune activation by polyriboinosinic-polyribocytidilic acid injection produces synaptic dysfunction but not neuronal loss in the hippocampus of juvenile rat offspring. Brain Res. 2010;1363:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baharnoori M, Brake WG, Srivastava LK. Prenatal immune challenge induces developmental changes in the morphology of pyramidal neurons of the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of rats. Schizophr Res. 2009;107:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowe GC, Luheshi GN, Williams S. Maternal infection and fever during late gestation are associated with altered synaptic transmission in the hippocampus of juvenile offspring rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1563–R1571. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90350.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanté F, Meunier J, Guiramand J, De Jesus Rerreira MC, Cambonie G, Aimar R, Cohen-Solal C, Maurice T, Vignes M, Barbanel G. Late N-acetylcysteine treatment prevents the deficits induced in the offspring of dams exposed to an immune stress during gestation. Hippocampus. 2008;18:602–609. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beloosesky R, Gayle DA, Ross MG. Maternal N-acetylcysteine suppresses fetal inflammatory cytokine responses to maternal lipopolysaccharide. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1053–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paintlia MK, Paintlia AS, Barbosa E, Singh I, Singh AK. N-acetylcysteine prevents endotoxin-induced degeneration of oligodendrocyte progenitors and hypomyelination in developing rat brain. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:347–361. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith SE, Li J, Garbett K, Mirnics K, Patterson PH. Maternal immune activation alters fetal brain development through interleukin-6. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10695–10702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2178-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsiao EY, Patterson PH. Activation of the maternal immune system causes endocrine changes in the placenta via IL-6. Brain Behav Immun. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.12.017. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girard S, Tremblay L, Lepage M, Sebire G. IL-1 receptor antagonist protects against placental and neurodevelopmental defects induced by maternal inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;184:3997–4005. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer U, Murray PJ, Urwyler A, Yee BK, Schedlowski M, Feldon J. Adult behavioral and pharmacological dysfunctions following disruption of the fetal brain balance between pro-inflammatory and IL-10-mediated anti-inflammatory signaling. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:208–221. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borzychowski AM, Sargent IL, Redman CW. Inflammation and pre-eclampsia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patterson PH. Brain-Immune Dialogues and what they mean for autism, schizophrenia and depression. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2011. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boris M, Kaiser CC, Goldblatt A, Elice MW, Edelson SM, Adams JB, Feinstein DL. Effect of pioglitazone treatment on behavioral symptoms in autistic children. J Neuroinflammation. 2007;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe Y, Someya T, Nawa H. Cytokine hypothesis of schizophrenia pathogenesis: evidence from human studies and animal models. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;64:217–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markram H, Rinaldi T, Markram K. The intense world syndrome--an alternative hypothesis for autism. Front Neurosci. 2007;1:77–96. doi: 10.3389/neuro.01.1.1.006.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider T, Roman A, Basta-Kaim A, Kubera M, Budziszewska B, Schneider K. Gender-specific behavioral and immunological alterations in an animal model of autism induced by prenatal exposure to valproic acid. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:728–740. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolozsi E, Mackenzie RN, Roullet FI, Decatanzaro D, Foster JA. Prenatal exposure to valproic acid leads to reduced expression of synaptic adhesion molecule neuroligin 3 in mice. Neuroscience. 2009;163:1201–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rinaldi T, Silberberg G, Markram H. Hyperconnectivity of local neocortical microcircuitry induced by prenatal exposure to valproic acid. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:763–770. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markram K, Rinaldi T, La Mendola D, Sandi C, Markram H. Abnormal fear conditioning and amygdala processing in an animal model of autism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:901–912. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider T, Turczak J, Przewlocki R. Environmental enrichment reverses behavioral alterations in rats prenatally exposed to valproic acid: Issues for a therapeutic approach in autism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:36–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernardet M, Crusio WE. Fmr1 KO mice as a possible model of autistic features. ScientificWorldJournal. 2006;6:1164–1176. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bear MF, Huber KM, Warren ST. The mGluR theory of fragile X mental retardation. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva AJ, Ehninger D. Adult reversal of cognitive phenotypes in neurodevelopmental disorders. J Neurodev Disord. 2009;1:150–157. doi: 10.1007/s11689-009-9018-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chahrour M, Zoghbi HY. The story of Rett syndrome: From clinic to neurobiology. Neuron. 2007;56:422–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cobb S, Guy J, Bird A. Reversibility of functional deficits in experimental models of Rett syndrome. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38:498–506. doi: 10.1042/BST0380498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kline DD, Ogier M, Kuze DL, Katz DM. Exogenous brain-derived neurotrophic factor rescues synaptic dysfunction in Mecp2-null mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5303–5310. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5503-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lonetti G, Angelucci A, Morando L, Boggio EM, Giustetto M, Pizzorusso T. Early environmental enrichment moderates the behavioral and synaptic phenotype of MeCP2 null mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yates JR. Tuberous sclerosis. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:1065–1073. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma A, Hoeffer CA, Takayasu Y, Miyawaki T, McBride SM, Klann E, Zukin RS. Dysregulation of mTOR signaling in Fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci. 2010;30:694–702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3696-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ehninger D, Silva AJ. Rapamycin for treating Tuberous sclerosis and autism spectrum disorders. Trends Mol Med. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.10.002. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Vries PJ. Targeted treatments for cognitive and neurodevelopmental disorders in Tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ehninger D, Sano Y, de Vries PJ, Dies K, Franz D, Geschwind DH, Kaur M, Lee YS, Li W, Lowe JK, Nakagawa JA, Sahin M, Smith K, Whittemore V, Silva AJ. Gestational immune activation and TSC2 haploinsufficiency cooperate to disrupt social behavior in mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.115. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Betancur C, Sakurai T, Buxbaum JD. The emerging role of synaptic cell-adhesion pathways in the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:402–412. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Südhof TC. Neuroligins and neurexins link synaptic function to cognitive disease. Nature. 2008;455:903–911. doi: 10.1038/nature07456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hung AY, Futai K, Sala C, Valtschanoff JG, Ryu J, Woodworth MA, Kidd FL, Sung CC, Mihakawa T, Bear MF, Weinberg RJ, Sheng M. Smaller dendritic spines, weaker synaptic transmission, but enhanced spatial learning in mice lacking Shank1. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1697–1708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3032-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tabuchi K, Blundell J, Etherton MR, Hammer RE, Liu X, Powell CM, Sudhof TC. A neuroligin-3 mutation implicated in autism increases inhibitory synaptic transmission in mice. Science. 2007;318:71–76. doi: 10.1126/science.1146221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blundell J, Blaiss CA, Etherton MR, Espinosa F, Tabuchi K, Walz C, Bolliger MF, Sudhof TC, Powell CM. Neuroligin-1 deletion results in impaired spatial memory and increased repetitive behavior. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2115–2129. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4517-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jamain S, Radyushkin K, Hammerschmidt K, Granon S, Boretius S, Varoqueaux F, Ramanantsoa N, Gallego J, Ronnenberg A, Winter D, Frahm J, Fischer J, Bourgeron T, Ehrenreich H, Brose N. Reduced social interaction and ultrasonic communication in a mouse model of monogenic heritable autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1710–1715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711555105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alarcón M, Abrahams AM, Stone JL, Duvall JA, Perederly JV, Bomar JM, Sebat J, Wigler M, Martin CL, Ledbetter DH, Nelson SE, Cantor RM, Geschwind DH. Linkage, association, and gene-expression analyses identify CNTNAP2 as an autism-susceptibility gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Panaitof SC, Abrahams BS, Dong H, Geschwind DH, White SA. Language-related Cntnap2 gene is differentially expressed in sexually dimorphic nuclei essential for vocal learning in songbirds. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:1995–2018. doi: 10.1002/cne.22318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vernes SC, Newbury DF, Abrahams BS, Winchester L, Nicod J, Groszer M, Alarcon M, Oliver PL, Davies KE, Geschwind DH, Monaco AP, Fisher SE. A functional genetic link between distinct developmental language disorders. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2337–2345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Insel TR. The challenge of translation in social neuroscience: A review of oxytocin, vasopressin, and affiliative behavior. Neuron. 2010;65:768–779. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ross HE, Young LJ. Oxytocin and the neural mechanisms regulating social cognition and affiliative behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:534–547. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pearson BL, Pobbe RL, Defensor EB, Oasay L, Bolivar VJ, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. Motor and cognitive stereotopies in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse model of autism. Genes Brain Behav. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00659.x. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Benno R, Smimova Y, Vera S, Liggett A, Schanz N. Exaggerated responses to stress in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse: an unusual behavioral phenotype. Behav Brain Res. 2009;197:462–465. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Amaral DG, Schumann CM, Nordahl CW. Neuroanatomy of autism. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buie T, Fuchs GJ, Furuta GT, Kooros K, Levy J, Lewis JD, Wershil BK, Winter H. Recommendations for evaluation and treatment of common gastrointestinal problems in children with ASDs. Pediatrics. 2010;125:S19–S29. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1878D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Careaga M, Van de Water J, Ashwood P. Immune dysfunction in autism: A pathway to treatment. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Short SJ, Lubach GR, Karasin AI, Olsen CW, Styner M, Knickmeyer RC, Gilmore JH, Coe CL. Maternal influenza infection during pregnancy impacts postnatal brain development in the rhesus monkey. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:965–973. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martin LA, Ashwood P, Braunschweig D, Cabanlit M, de Water JV, Amaral DG. Stereotopies and hyperactivity in rhesus monkeys exposed to IgG from mothers of children with autism. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:806–816. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]