Abstract

Disruption of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT signaling pathway can lead to apoptosis in cancer cells. Previously we identified a lead sulfonamide that selectively bound to the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of AKT and induced apoptosis when present at low micromolar concentrations. To examine the effects of structural modification, a set of sulfonamides related to the lead compound was designed, synthesized, and tested for binding to the expressed PH domain of AKT using a surface plasmon resonance-based competitive binding assay. Cellular activity was determined by means of an assay for pAKT production and a cell killing assay using BxPC3 cells. The most active compounds in the set are lipophilic and possess an aliphatic chain of the proper length. Results were interpreted with the aid of computational modeling. This paper represents the first structure-activity relationship (SAR) study of a large family of AKT PH domain inhibitors. Information obtained will be used in the design of the next generation of inhibitors of AKT PH domain function.

Keywords: AKT, PH domain, anticancer, drug design, drug development

1. Introduction

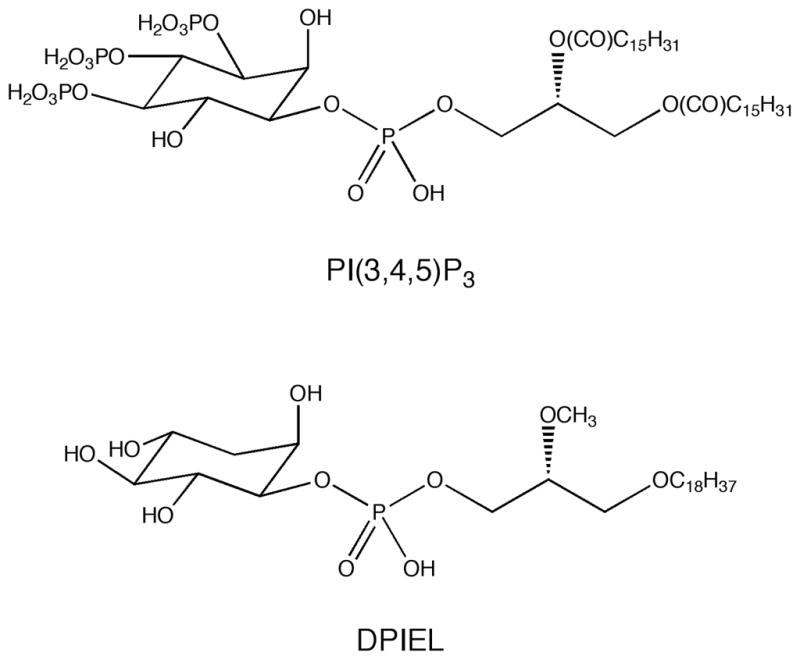

Pleckstrin homology (PH) domains containing 100–120 amino acids are found in over 500 human proteins1 and are the 11th most common domain in the human proteome.2 A subset of 40 PH domains are known to bind phosphorylated phosphatidylinositol (PI) lipids held in cell membranes. PI phosphorylation and the subsequent binding of PH domain-containing proteins are vital components of signal transduction pathways that regulate cell growth and survival.3,4 For example, phosphorylation of PI(4,5)P2 to produce PI(3,4,5)P3 (see Figure 1) by PI3K signals the recruitment and binding of AKT to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane via recognition of the PH domain.5,6 This translocation allows phosphorylation of AKT at Thr308 by the plasma membrane-bound PDPK1.7 Phosphorylation at the Ser473 residue occurs either by the ILK, by the kinase activity of AKT itself, or by rictor-mTOR.8 Once fully phosphorylated, AKT translocates through the cytosol to the nucleus where it phosphorylates a variety of downstream targets. AKT promotes cell survival by activating CREB,9 and promotes proliferation by activating p70S6 kinase10 and GSK-3β11 which contribute to cyclin D accumulation of cell cycle entry. Furthermore, AKT acts as a mediator for VEGF production and angiogenesis by phosphorylation of mTOR.12 Given its importance in proliferation and survival signaling, AKT is an important target for cancer drug discovery.13

Figure 1.

The structures of PI(3,4,5)P3 and DPIEL

Several previous attempts to develop AKT inhibitors have led to compounds that bind to the ATP-binding pocket14 or behave as allosteric inhibitors.15 Due to the similarity of this pocket among serine/threonine kinases, achieving target specificity has been difficult. Our previous studies involving a D-3-deoxyphosphatidylinositol ether lipid, DPIEL (Figure 1),16,17 provided proof-of-principle for using PH domains as drug targets.17–24 DPIEL exhibits a high binding affinity and selectivity for the PH domain of AKT. In addition, DPIEL does not bind to other PH domain-containing proteins, including PDPK1, IRS-1, mSOS, and βARK. Although DPIEL exhibits significant antitumor activity, unfortunately it is not a useful drug candidate because of its pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties.16

Previously, we used a crystal structure of the PH domain of AKT and in silico screening to cull from libraries compounds expected to bind to the target domain.25,26 Compounds selected from these libraries were purchased or prepared, then tested for binding to AKT and for inhibition of AKT function in several cancer cell lines. Compound 1, a sulfonamide (see Table 1), was among the leads identified, and so several analogs of 1 were prepared and tested in vitro. The best analog, compound 29 herein, was then tested in vivo where it exhibited good antitumor activity in a mouse xenograft model of pancreatic cancer cells in immunocompromised mice.26,27 This work provided for the first time proof-of-principle for further development of sulfonamides as drugs that bind to the PH domain of AKT, inhibit its function, and as a result exhibit antitumor activity. Presented herein are studies with compounds 2–47, derivatives of 1 that were synthesized and tested in an effort to generate structure-activity relationships (SARs) to guide further development of potential drug candidates.

Table 1.

Structures, yields, and melting points of compounds 1–47. Details of the syntheses are given in the Experimental Section (compounds 26–40) or in the Supplementary Data (compounds 1–25 and 41–47).

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | Yield (%) | mp (°C) |

| 1a | H | H | H | NH2 | 49b | 224–225 |

| 2 | CH3 | H | H | NH2 | 72b | 207–208 |

| 3 | CH2CH3 | H | H | NH2 | 69b | 190–191 |

| 4 | C(CH3)3 | H | H | NH2 | 74b | 220–221 |

| 5 | CH2CO2H | H | H | NH2 | 82c | 209–210 |

| 6 | CH2OH | H | H | NH2 | 68b | 89–90 |

| 7 | SO2NH2 | H | H | NH2 | 57b | 241–242 |

| 8a | H | H | H | NH(CO)CH3 | 95 | 216–217 |

| 9 | CH3 | H | H | NH(CO)CH3 | 97 | 239–240 |

| 10 | CH2CH3 | H | H | NH(CO)CH3 | 70 | 197–198 |

| 11 | C(CH3)3 | H | H | NH(CO)CH3 | 84 | 137–138 |

| 12 | CH2CO2H | H | H | NH(CO)CH3 | 88d | 206–207 |

| 13 | CH2CO2CH2CH3 | H | H | NH(CO)CH3 | 76 | 156–157 |

| 14 | CO2CH2CH3 | H | H | NH(CO)CH3 | 73 | 201–202 |

| 15 | CH2OH | H | H | NH(CO)CH3 | 82 | 101–102 |

| 16 | SO2NH2 | H | H | NH(CO)CH3 | 63 | 280–281 |

| 17a | H | H | H | NH(CO)(CH2)8CH3 | 95e | 151–152 |

| 18 | CH3 | H | H | NH(CO)(CH2)8CH3 | 95e | 141–142 |

| 19 | CH2CH3 | H | H | NH(CO)(CH2)8CH3 | 97e | 121–122 |

| 20 | C(CH3)3 | H | H | NH(CO)(CH2)8CH3 | 98e | 156–157 |

| 21 | CH2CO2H | H | H | NH(CO)(CH2)8CH3 | 83d | 190–191 |

| 22 | CH2CO2CH2CH3 | H | H | NH(CO)(CH2)8CH3 | 63 | 89–90 |

| 23 | CO2CH2CH3 | H | H | NH(CO)(CH2)8CH3 | 65 | 101–102 |

| 24 | CH2OH | H | H | NH(CO)(CH2)8CH3 | 73 | 69–70 |

| 25 | SO2NH2 | H | H | NH(CO)(CH2)8CH3 | 60 | 242–243 |

| 26 | H | H | H | (CH2)3CH3 | 59 | 120–121 |

| 27 | H | H | H | (CH2)5CH3 | 58 | 125–126 |

| 28 | H | H | H | (CH2)7CH3 | 55 | 123–124 |

| 29a | H | H | H | (CH2)11CH3 | 51 | 126–127 |

| 30 | H | H | H | (CH2)13CH3 | 47 | 116–117 |

| 31 | H | H | H | (CH2)15CH3 | 46 | 118–119 |

| 32 | H | H | H | (CH2)17CH3 | 51 | 116–117 |

| 33 | CH3 | H | H | (CH2)11CH3 | 84 | 149–150 |

| 34 | CH2CH3 | H | H | (CH2)11CH3 | 59 | 93–94 |

| 35 | C(CH3)3 | H | H | (CH2)11CH3 | 87 | 117–118 |

| 36 | CH2CO2H | H | H | (CH2)11CH3 | 86d | 194–195 |

| 37 | CH2CO2CH2CH3 | H | H | (CH2)11CH3 | 54 | 110–111 |

| 38 | CO2CH2CH3 | H | H | (CH2)11CH3 | 78 | 134–135 |

| 39 | CH2OH | H | H | (CH2)11CH3 | 65 | 138–139 |

| 40 | SO2NH2 | H | H | (CH2)11CH3 | 63 | 249–250 |

| 41 | H | H | H | C6H5 | 57 | 250–251 |

| 42 | CH2CH3 | H | H | C6H5 | 43 | 146–147 |

| 43 | CH2OH | H | H | C6H5 | 52 | 239–240 |

| 44a | H | H | H | NH(CO)CH2O(CH2CH2O)2CH3 | 62 | oil |

| 45 |

|

68 | 54–55 | |||

| 46 | H | (CH2)11CH3 | H | H | 13 | 159–161 |

| 47 | H | H | (CH2)11CH3 | H | 91 | 98–99 |

Compound previously reported; see Reference 26.

Yield of hydrolysis of the corresponding acetamide derivative.

Yield of hydrolysis of compound 13.

Yield of hydrolysis of the corresponding ethyl ester.

Yield of acylation of the corresponding aniline derivative.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemical Synthesis

General Experimental

All commercial reagents were used without further purification. Analytical TLC was carried out on pre-coated Silica Gel F254 plates. TLC plates were visualized with UV light (254nm). 1H NMR spectra were recorded at 250, 300, or 500 MHz and 13C NMR spectra at 62.5, 75, or 125 MHz. Chemical shifts (δ) are expressed in ppm and are internally referenced (7.26 ppm for 1H NMR and 77.00 ppm for 13C NMR in CDCl3, 2.50 ppm for 1H NMR and 39.50 ppm for 13C NMR in DMSO-d6). Mass spectra and high resolution mass spectra were obtained in the Mass Spectrometry Laboratory in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Arizona. Melting points are uncorrected.

4-Butyl-N-(1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamide (26)

To a solution of butylbenzene (4.13 g, 30.8 mmol) in CHCl3 (50 mL) was added chlorosulfonic acid (17.0 mL, 29.8 g, 256 mmol).28 The mixture was stirred at rt for 20 h. The mixture was poured on ice (200 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 100 mL). The combined extracts were washed with water, aqueous NaHCO3, and water, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The resulting yellow oily residue, crude p-butylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (ca 88% yield), was used without further purification in the next reaction; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.94 (3, t, J = 7 Hz), 1.34–1.41 (2, m), 1.62–1.67 (2, m), 2.73 (2, t, J = 8 Hz), 7.41 (2, d, J = 8 Hz), 7.94 (2, d, J = 8 Hz).

To a stirred solution of 2-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole (2.0 g, 19.7 mmol) in pyridine (30 mL) under argon at −20 °C was added crude p-butylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (4.89 g, ca 21 mmol) over 10 min. The reaction mixture was allowed to attain rt and stirred for 16 h. Water (300 mL) was added to quench the reaction. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2, the organic extracts washed with 2N HCl (2 × 150 mL), brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was subjected to flash chromatography on silica gel eluted with CH2Cl2:MeOH 33:1 to give the product 26 (3.46 g, 11.6 mmol, 59% yield) as a solid, mp 120–121 °C; RP HPLC tR 6.06 min (4.6 × 250 mm C18 column eluted with CH3CN, 0.5 mL/min); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.91 (3, t, J = 7 Hz), 1.29–1.37 (2, m), 1.56–1.61 (2, m), 2.65 (2, t, J = 7 Hz), 7.27 (2, d, J = 8 Hz), 7.84 (2, d, J = 8 Hz), 8.25 (1, s); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) 13.9, 22.3, 33.2, 33.6, 126.5, 129.1, 138.1, 142.7, 148.6, 167.4; HRMS (Q-TOF) calculated for C12H16N3O2S2 298.0684, observed 298.0695 (M+H)+; calculated for C12H15N3NaO2S2 320.0503, observed 320.0361 (M+Na)+.

4-Hexyl-N-(1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamide (27)

In a similar manner, hexylbenzene (5.00 g, 30.8 mmol) and chlorosulfonic acid (17.0 mL, 29.8 g, 256 mmol) gave crude p-hexylbenzenesulfonyl chloride as a yellow oily residue (ca 81% yield); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (3, t, J = 7 Hz), 1.30–1.35 (6, m), 1.55–1.63 (2, m), 2.59 (2, t, J = 8 Hz), 7.38 (2, d, J = 8 Hz), 7.89 (2, d, J = 8 Hz). Reaction of 2-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole (2.0 g, 19.7 mmol) with p-hexylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (5.48 g, ca 21 mmol) afforded the product 27 (3.72 g, 11.4 mmol, 58% yield) as a solid, mp 125–126 °C, after flash chromatography on silica gel eluted with CH2Cl2:MeOH 33:1; RP HPLC tR 6.79 min (4.6 × 250 mm C18 column eluted with CH3CN, 0.5 mL/min); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (3, t, J = 7 Hz), 1.28 (6, m), 1.58 (2, m), 2.63 (2, t, J = 7 Hz), 7.27 (2, d, J = 8 Hz), 7.83 (2, d, J = 8 Hz), 8.24 (1, s); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) 14.1, 22.6, 28.9, 31.1, 31.6, 35.9, 126.5, 129.0, 138.1, 142.6, 148.6, 167.4; HRMS (Q-TOF) calculated for C14H20N3O2S2 326.0997, observed 326.0931 (M+H)+; calculated for C14H19N3NaO2S2 348.0816, observed 348.0816 (M+Na)+.

4-Octyl-N-(1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamide (28)

In a similar manner, 1-phenyloctane (5.86 g, 30.8 mmol) and chlorosulfonic acid (17.0 mL, 29.8 g, 256 mmol) gave crude p-octylbenzenesulfonyl chloride as a yellow oily residue (ca 80% yield); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.87 (3, t, J = 7 Hz), 1.27–1.32 (10, m), 1.64–1.66 (2, m), 2.72 (2, t, J = 8 Hz), 7.42 (2, d, J = 8 Hz), 7.93 (2, d, J = 8 Hz). Reaction of 2-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole (2.0 g, 19.7 mmol) with p-octylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (6.06 g, ca 21 mmol) afforded the product 28 (3.83 g, 10.8 mmol, 55% yield) as a solid, mp 123–124 °C, after flash chromatography on silica gel eluted with CH2Cl2:MeOH 33:1; RP HPLC tR 8.17 min (4.6 × 250 mm C18 column eluted with CH3CN, 0.5 mL/min); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.87 (3, t, J = 7 Hz), 1.36 (10, m), 1.59 (2, m), 2.63 (2, t, J = 7 Hz), 7.27 (2, d, J = 8 Hz), 7.82 (2, d, J = 8 Hz), 8.23 (1, s); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) 14.1, 22.6, 29.2, 29.3, 29.4, 31.1, 31.8, 35.9, 126.5, 129.0, 138.1, 142.6, 148.7, 167.3; HRMS (Q-TOF) calculated for C16H24N3O2S2 354.1310, observed 354.1211 (M+H)+; calculated for C16H23N3NaO2S2 376.1129, observed 376.1154 (M+Na)+.

4-Dodecyl-N-(1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamide (29)

The syntheses of p-dodecylbenzenesulfonyl chloride and compound 29 have previously been described; see the supplementary data associated with reference 26.

4-Tetradecyl-N-(1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamide (30)

In a similar manner, 1-phenyltetradecane (0.69 g, 2.5 mmol) and chlorosulfonic acid (0.50 mL, 7.5 mmol) gave p-tetradecylbenzenesulfonyl chloride as a white solid (0.63 g, 1.7 mmol, 68%), Rf 0.18 (50% EtOAc/hexanes), mp 32–33 °C, after chromatography on silica gel (70–230 mesh) with hexanes/EtOAc (49:1); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (3, t, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.25 (22, m), 1.65 (2, m), 2.72 (2, t, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.42 (2, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.93 (2, d, J = 8.4 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) 14.1, 22.6, 29.1, 29.3, 29.5, 29.6, 29.7, 30.9, 31.9, 36.0, 126.9, 129.5, 141.7, 151.6. Reaction of 2-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole (179 mg, 1.77 mmol) with p-tetradecylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (440 mg, 1.18 mmol) afforded the product 30 (240 mg, 0.55 mmol, 47% yield), Rf 0.46 (5% MeOH/CH2Cl2), as a solid, mp 116–117 °C, after chromatography on silica gel (70–230 mesh) eluted with CH2Cl2:MeOH 19:1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (3, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 1.25 (22, m), 1.60 (2, m), 2.64 (2, t, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.29 (2, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.84 (2, d, J = 8.4Hz), 8.23 (1, s); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) 14.1, 22.6, 29.2, 29.3, 29.4, 29.5, 29.6, 31.1, 31.9, 35.9, 126.5, 128.9, 138.1, 142.6, 148.6, 167.4; LRMS (ESI+) calculated for C22H36N3O2S2 438.2, observed 438.3 (M+H)+; HRMS (ESI+, m/z) calculated for C22H36N3O2S2 438.2243, observed 438.2243 (M+H)+.

4-Hexadecyl-N-(1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamide (31)

In a similar manner, 1-phenylhexadecane (0.76 g, 2.5 mmol) and chlorosulfonic acid (0.50 mL, 7.5 mmol) gave p-hexadecylbenzenesulfonyl chloride as a white solid (0.71 g, 1.8 mmol, 72%), mp 35–36 °C, after chromatography on silica gel eluted with hexanes/EtOAc (49:1); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (3, t, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.25 (26, m), 1.62 (2, m), 2.72 (2, t, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.42 (2, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.95 (2, d, J = 8.4 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) 14.4, 22.9, 29.4, 29.64, 29.8, 29.9, 31.2, 32.2, 36.3, 127.3, 129.8, 142.0, 151.9. Reaction of 2-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole (228 mg, 2.25 mmol) with p-hexadecylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (600 mg, 1.50 mmol) afforded the product 31 (320 mg, 0.69 mmol, 46% yield), Rf 0.46 (5% MeOH/CH2Cl2), as a solid, mp 118–119 °C, after chromatography on silica gel (70–230 mesh) eluted with CH2Cl2:MeOH 19:1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (3, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 1.25 (26, m), 1.59 (2, m), 2.64 (2, t, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.29 (2, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.84 (2, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 8.23 (1, s); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) 14.1, 22.7, 29.2, 29.3, 29.4, 29.6, 29.7, 31.1, 31.9, 35.9, 126.5, 128.9, 138.1, 142.5, 148.7, 167.5; LRMS (ESI+) calculated for C24H40N3O2S2 466.3, observed 466.3 (M+H)+; HRMS (ESI+, m/z) calculated for C24H40N3O2S2 466.2556, observed 466.2558 (M+H)+.

4-Octadecyl-N-(1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamide (32)

In a similar manner, 1-phenyloctadecane (0.84 g, 2.5 mmol) and chlorosulfonic acid (0.50 mL, 7.5 mmol) gave p-octadecylbenzenesulfonyl chloride as a white solid (0.60 g, 1.4 mmol, 56%), mp 43–44 °C, after chromatography on silica gel eluted with hexanes/EtOAc (49:1); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.86 (3, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 1.25 (30, m), 1.65 (2, m), 2.72 (2, t, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.42 (2, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.93 (2, d, J = 8.4 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) 14.1, 22.7, 29.2, 29.4, 29.5, 29.7, 30.9, 31.9, 36.0, 127.1, 129.6, 141.8, 151.7. Reaction of 2-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole (177 mg, 1.75 mmol) with p-octadecylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (500 mg, 1.17 mmol) afforded the product 32 (296 mg, 0.60 mmol, 51% yield), Rf 0.46 (5% MeOH/CH2Cl2), as a solid, mp 116–117 °C, after chromatography on silica gel (70–230 mesh) eluted with CH2Cl2:MeOH 19:1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.86 (3, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 1.25 (30, m), 1.60 (2, m), 2.64 (2, t, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.29 (2, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.82 (2, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 8.21 (1, s); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) 14.0, 22.7, 29.2, 29.3, 29.4, 29.5, 29.6, 29.7, 31.1, 31.9, 35.9, 126.5, 128.9, 138.1, 142.6, 148.6, 167.4; LRMS (ESI+) calculated for C26H44N3O2S2 494.3, observed 494.2 (M+H)+; HRMS (ESI+, m/z) calculated for C26H44N3O2S2 494.2869, observed 494.2869 (M+H)+.

4-Dodecyl-N-(5-methyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamide (33)

A suspension of 2-amino-5-methyl-1,3,4-thiadiazole (150 mg, 1.3 mmol) in pyridine (0.5 mL) was stirred and cooled in an ice bath while p-dodecylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (300 mg, 0.87 mmol) was added slowly. The reaction mixture was allowed to attain rt, then heated in an oil bath at 95 °C for 1 h. The reaction mixture was then cooled, added to aqueous 10% HCl (5 mL), and the resulting mixture extracted with EtOAc (3 × 10 mL). The organic extracts were washed with water, brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and volatiles evaporated in vacuo to yield a solid mass. Chromatography on silica gel (70–230 mesh) eluted with CH2Cl2:MeOH 49:1 gave the product 33 (310 mg, 0.73 mmol, 84%), Rf 0.23 (50% EtOAc/hexanes). Recrystallization from EtOAc:hexanes 7:3 gave an analytical sample, mp 149–150 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (3, t, J = 7.0 Hz), 1.20–1.36 (18, m), 1.54–1.63 (2, m), 2.51 (3, s), 2.63 (2, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.25 (2, d, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.82 (2, d, J = 7.5 Hz), 12.36 (1, br s); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 14.1, 16.5, 22.7, 29.2, 29.3, 29.4, 29.5, 29.6, 31.1, 31.9, 35.9, 126.4, 128.8, 138.3, 148.3, 154.1, 168.6; LRMS (ESI+, m/z) calculated for C21H34N3O2S2 424.2092 observed 424.20 (M+H)+; HRMS (ESI+, m/z) calculated for C21H34N3O2S2 424.2092, observed 424.2085 (M + H)+.

4-Dodecyl-N-(5-ethyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamide (34)

In a similar manner, reaction of 2-amino-5-ethyl-1,3,4-thiadiazole (169 mg, 1.3 mmol) and p-dodecylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (300 mg, 0.87 mmol) gave the product 34 (225 mg, 0.51 mmol, 59%), Rf 0.27 (50% EtOAc/hexanes), after chromatography on silica gel (70–230 mesh) eluted with CH2Cl2:MeOH 49:1. Recrystallization from EtOAc:hexanes 7:3 gave an analytical sample, mp 93–94 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (3, t, J = 6.5 Hz), 1.20–1.36 (18, m), 1.33 (3, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 1.54–1.63 (2, m), 2.63 (2, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 2.84 (2, q, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.25 (2, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.83 (2, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 12.30 (1, br s); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.6, 14.1, 22.7, 24.4, 29.2, 29.3, 29.4, 29.5, 29.6, 31.1, 31.9, 35.9, 126.5, 128.8, 138.4, 148.2, 160.1 168.2; LRMS (ESI+, m/z) calculated for C22H36N3O2S2 438.2249, observed 438.30 (M+H)+; HRMS (ESI+, m/z) calculated for C22H36N3O2S2 438.2249, observed 438.2247 (M + H)+.

N-(5-tert-Butyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)-4-dodecylbenzenesulfonamide (35)

In a similar manner, reaction of 2-amino-5-tert-butyl-1,3,4-thiadiazole (204 mg, 1.3 mmol) and p-dodecylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (300 mg, 0.87 mmol) gave the product 35 (350 mg, 0.75 mmol, 86%), Rf 0.45 (50% EtOAc/hexanes), after chromatography on silica gel (70–230 mesh) eluted with CH2Cl2:MeOH 49:1. Recrystallization from EtOAc:hexanes 7:3 gave an analytical sample, mp 117–118 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (3, t, J = 6.5 Hz), 1.20–1.36 (18, m), 1.38 (9, s), 1.56–1.64 (2, m), 2.63 (2, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.25 (2, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.86 (2, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 12.24 (1, br s); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 14.1, 22.7, 29.2, 29.3, 29.4, 29.5, 29.6, 29.7, 31.1, 31.8, 35.8, 36.5, 126.5, 128.7, 138.5, 148.1, 167.8, 168.0; LRMS (ESI+, m/z) calculated for C24H40N3O2S2 466.3, observed 466.2 (M+H)+; HRMS (ESI+, m/z) calculated for C24H40N3O2S2 466.2562, observed 466.2562 (M + H)+.

2-(5-(4-Dodecylphenylsulfonamido)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)acetic Acid (36)

Distilled water (3.0 mL) and 10% aqueous NaOH (0.65 mL) were added to compound 37 (200 mg, 0.40 mmol) and the mixture was heated under reflux for 2 h. The pH of the solution was then adjusted to 4.0 by addition of 1.0 M HCl, the resulting precipitate was isolated by filtration, washed with cold water, and dried to give the product 36 (161 mg, 0.34 mmol, 85%), Rf 0.34 (20% MeOH/CH2Cl2), as a light yellow solid, mp 194–195 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.85 (3, t, J = 6.6 Hz), 1.23 (18, m), 1.53 (2, m), 2.57 (2, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 3.74 (2, s), 7.24 (2, d, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.61 (2, d, J = 7.8 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 14.0, 22.1, 28.8, 28.9, 29.1, 30.7, 31.3, 34.9, 37.4, 125.8,128.4, 141.2, 146.0, 153.3, 168.9, 170.8; LRMS (ESI+) calculated for C22H34N3O4S2 468.2, observed 468.2 (M+H)+; HRMS (ESI+, m/z) calculated for C22H34N3O4S2 468.1991, observed 468.1977 (M+H)+.

Ethyl 2-(5-(4-Dodecylphenylsulfonamido)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)acetate (37)

A suspension of ethyl 2-(5-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)acetate29 (2.0 g, 11.2 mmol) in pyridine (50 mL) was stirred and cooled in an ice bath while p-dodecylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (4.7 g, 13.5 mmol) was added slowly. The mixture was stirred at rt for 48 h, then heated in an oil bath at 90 °C for 15 min. The reaction mixture was then cooled to rt, poured into aqueous 10% HCl, and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 75 mL). The combined extracts were washed with water (2 × 50 mL), brine (2 × 50 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was subjected to chromatography on silica gel (70–230 mesh) eluted with CH2Cl2:MeOH 95:5 to give the product 37 (2.9 g, 5.9 mmol, 53%), Rf 0.64 (10% MeOH/CH2Cl2). Recrystallization from EtOAc/hexanes gave an analytical sample, mp 110–111 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (3, t, J = 7.0 Hz), 1.20–1.28 (18, m), 1.32 (3, t, J = 7.0 Hz), 1.58–1.66 (2, m), 2.64 (2, t, J = 7.0 Hz), 3.87 (2, s), 4.25 (2, q, J = 7.0 Hz), 7.26 (2, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.82 (2, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 10.91 (1, br s); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 14.0, 14.1, 22.6, 29.2, 29.3, 29.4, 29.5, 29.6, 31.1, 31.9, 35.9, 36.4, 62.2, 126.4, 128.8, 138.2, 148.3, 151.2, 167.3, 168.6; LRMS (ESI+) calculated for C24H38N3O4S3 496.2, observed 496.2 (M+H)+; HRMS (ESI+, m/z) calculated for C24H38N3O4S3 496.2304, observed 496.2295 (M+H)+.

Ethyl 5-(4-Dodecylphenylsulfonamido)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-carboxylate (38)

In a similar manner, reaction of ethyl 5-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole-2-carboxylate30 (1.8 g, 10.4 mmol) with p-dodecylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (4.3 g, 12.5 mmol) gave the product 38 (3.9 g, 8.1 mmol, 78%), Rf 0.44 (10% MeOH/CH2Cl2), after chromatography on silica gel (70–230 mesh) eluted with CH2Cl2:MeOH 9:1. Recrystallization from EtOAc/hexanes gave an analytical sample, mp 134–135 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.84 (3, t, J = 7.0 Hz), 1.17–1.30 (18, m), 1.31 (3, t, J = 7.0 Hz), 1.50–1.51 (2, m), 2.62 (2, t, J = 7.0 Hz), 4.36 (2, q, J = 7.0 Hz), 7.38 (2, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.72 (2, d, J = 8.0 Hz); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 14.3, 22.6, 29.1, 29.2, 29.3, 29.4, 29.5, 31.1, 31.8, 35.4, 63.4, 126.4, 129.4, 139.1, 147.7, 148.3, 157.9, 168.1; LRMS (ESI+) calculated for C23H36N3O4S3 482.2, observed 482.1 (M+H)+; HRMS (ESI+, m/z) calculated for C23H36N3O4S3 482.2140, observed 482.2134 (M+H)+.

4-Dodecyl-N-(5-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamide (39)

In a similar manner, reaction of 2-amino-5-hydroxymethyl-1,3,4-thiadiazole31 (4.0 g, 30.5 mmol) with p-dodecylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (11.6 g, 33.6 mmol) gave the product 39 (8.7 g, 19.8 mmol, 65% yield), Rf 0.58 (10% MeOH/CH2Cl2), as a solid, mp 138–139 °C, after chromatography on silica gel (70–230 mesh) eluted with CH2Cl2:MeOH 19:1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.84 (3, t, J = 6.6 Hz), 1.22 (18, m), 1.54–1.57 (2, m), 2.64 (2, t, J = 7.8 Hz), 4.57 (2, s), 6.05 (1, br s), 7.35 (2, d, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.67 (2, d, J = 7.8 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.9, 22.1, 28.6, 28.7, 28.8, 29.0, 30.6, 31.3, 34.9, 58.4, 125.8, 128.9, 139.2, 147.5, 161.1, 167.5; LRMS (ESI+) calculated for C21H34N3O3S2 440.2, observed 440.2 (M+H)+; HRMS (ESI+, m/z) calculated for C21H34N3O3S2 440.2042, observed 440.2029 (M+H)+.

5-(4-Dodecylphenylsulfonamido)-1,3,4-thiadiazole-2-sulfonamide (40)

A suspension of 5-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazolo-2-sulfonamide32 (4.10 g, 22.8 mmol) in anhydrous acetonitrile (100 mL) was stirred and cooled in an ice bath. Triethylamine (2.5 g, 25 mmol) and a solution of p-dodecylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (8.6 g, 25 mmol) in anhydrous acetonitrile (60 mL) were added, the reaction mixture allowed to attain rt, and then stirred for 48 h. Volatiles were removed in vacuo and the residue was washed with 10% aqueous HCl (100 mL) and water (100 mL) in order to eliminate salts. The residue was subjected to chromatography on silica gel (70–230 mesh) eluted with CH2Cl2:MeOH 19:1 to give the product 40 (7.0 g, 14.3 mmol, 63%), Rf 0.56 (10% MeOH/CH2Cl2). Recrystallization from absolute ethanol and a second chromatography gave an analytical sample, mp 249–250 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.85 (3, t, J = 6.6 Hz), 1.23 (18, m), 1.55 (2, m), 2.58 (2, t, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.23 (2, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.34 (2, s), 7.59 (2, d, J = 8.1 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.9, 22.1, 28.7, 28.9, 29.0, 29.1, 30.8, 31.3, 34.9, 126.2, 127.8, 143.3, 145.1, 161.2, 170.9; LRMS (ESI−) calculated for C20H31N4O4S3 487.2, observed 487.1 (M-H)−; HRMS (ESI−, m/z) calculated for C20H31N4O4S3 487.1513, observed 487.1514 (M-H)−.

2.2 Biological studies

2.2.1 Expression of recombinant AKT PH domain

Recombinant mouse AKT1 PH domain amino acids 1–111 (UBI/Millipore, Charlottesville, VA) was cloned by PCR into EcoRI/XhoI sites in pGEX-4T1 inducible bacterial expression plasmid (GeneStorm, InVitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) transformed into BL21(DE3) E. Coli. Expression and purification of the protein were performed as previously described.15

2.2.2 Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) spectroscopy binding assays

Competitive binding assays were performed with a Biacore 2000, using the Biacore 2000 Control Software v3.2 and BIAevaluation v4.1 analysis software (Biacore, Piscataway, NJ) as previously described.26 Briefly, PI-3,4,5-phosphates-biotin labeled liposomes (Echelon Biosciences, Salt Lake City, UT) were immobilized on SA chips (BR-1000-32) at a level of 600 response units (RUs). Small molecule analytes at concentrations ranging from one tenth to ten times the predicted KD were co-injected with 80nM PH domain GST-fusion protein (AKT1) at a flow rate of 30uL/min. Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) concentrations in all samples and running buffer were 1% (v/v) or less.

2.2.3 Cell assays

Cellular proliferation

A standard 96-well micro-cytoxicity assay was performed by plating cells at 5,000–10,000 cells per well (depending on cell doubling time) for a growth period of 4 days. Drugs were added directly to the media, dissolved in DMSO at various concentrations ranging from 1 to 50 μM. The endpoint was spectrophotometric determination of the reduction of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide.

Detection of pAKT

Human BxPC3 pancreatic cancer cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Cells were maintained in bulk culture in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 4.5 g/L glucose, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were passaged using 0.25% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA. Cells were confirmed to be mycoplasma free by testing them with an ELISA kit (Roche-Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). Drugs were freshly prepared in DMSO at a stock concentration of 10 mM and then added at 10μM final concentration directly into the culture media of the cells for 4 h. Following this treatment, cells were lysed as previously published26 and equal amounts of total cell lysate were loaded on a pSer473-AKT/Total AKT Meso Scale Discovery plate. The plate was read using a Sector Imager 2400A instrument (Meso Scale Discovery protein profiling system, Gaithersburg, MD).

2.3 Computational modeling

In a previous study33 GOLD docking and scoring34 was reported as the best combination for the analysis of interactions between the AKT PH domain and small molecules. Therefore, the GOLD package was employed for molecular docking studies in this work. During docking, the protein was kept as rigid while the flexibility of the ligand was explored. Flipping of the ring corners in the ligands was considered, and carboxylic acids were deprotonated. No early termination was allowed in docking. Other parameters and procedures were applied as previously described.33

3. Results

3.1 Chemistry

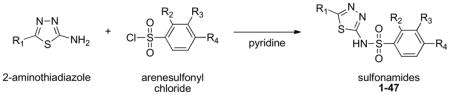

The structures, yields, and melting points of compounds 1–47 are given in Table 1. Compounds 1–4 and 8–10 are listed as being commercially available, but only 2 is inexpensive. Compounds 1–5, 7–10, and 16 are known and were prepared for this study according to literature procedures. Most of the remaining compounds were prepared by condensation of a 2-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole nucleophile with an arenesulfonyl chloride electrophile in the presence of pyridine. The 2-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazoles and arenesulfonyl chlorides used were either obtained from commercial sources or were prepared by known methods. Yields of these condensations were generally good to excellent. In some cases, substituent modification followed condensation to produce additional analogs (e.g., saponification of esters 13, 22, and 37 gave acids 12, 21, and 36, respectively). Compounds were purified by column chromatography and/or crystallization. Structures were confirmed by spectroscopic methods and purity ascertained to be ≥95% by TLC analysis or by RP HPLC analysis. Details of the syntheses and compound characterization for compounds 26–40 are given in the Experimental Section. Details of the syntheses and compound characterization data for compounds 1–25 and 41–47 are given in the Supplementary Data that accompanies this paper.

3.2 Bioassays

Results from bioassays of compounds 1–47 are given in Table 2 and Figure 2. Compounds were tested for their ability to compete with the binding of PI(3,4,5)P3 to the PH domain of AKT (reported as Ki) using a previously described surface plasmon resonance (SPR) competitive binding assay.26,27 Compounds 1 and 8 that bear hydrogen atoms at positions R1, R2, and R3 and an amino or acetamido substituent at position R4, respectively, exhibited no ability to block PI(3,4,5)P3 binding (Ki > 50 μM). As a result, Ki values for compounds 2–7 and 9–16 were not determined. Compounds 17–24 that bear hydrogen atoms at positions R2 and R3 and a decamido substituent at position R4, but vary at R1, were shown to compete with the binding of PI(3,4,5)P3 with most Ki values near 10 μM. Replacement of the hydrophobic decamido substituent of 17 with a more hydrophilic PEG-containing amide in 44 reduced inhibition of PI(3,4,5)P3 binding. Compounds 26–32 bear hydrogen atoms at positions R1, R2, and R3 and a normal alkyl substituent of variable length at position R4. As previously reported, an aliphatic chain of the proper length (~C12H25) is necessary for optimal inhibition of PI(3,4,5)P3 binding.27 The Ki values for compounds 33–40 that bear hydrogen atoms at positions R2 and R3, a C12H25 substituent at position R4, and an additional substituent (R1) at position 5 of the thiadiazole ring were unimproved relative to 29. Replacement of the C12H25 chain at R4 with a phenyl (compare 29 with 41, 34 with 42, and 39 with 43) or replacement of the thiadiazole ring with a phenyl (compare 29 with 45) was detrimental to inhibition of PI(3,4,5)P3 binding. Movement of the C12H25 chain from the para position to the ortho or meta position relative to the sulfonamide (compare 29 with 46 and 47) also reduced inhibition of PI(3,4,5)P3 binding.

Table 2.

Bioassay data and GOLD docking scores for compounds 1–47.

| Compound Number | Ki × 106 (M)a | pKia,b | Cell SurvivalcIC50d (μM) | GOLD Docking Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | >50e | IA | >300 | 50 |

| 2 | ND | ND | >300 | 52 |

| 3 | ND | ND | >300 | 54 |

| 4 | ND | ND | >300 | 55 |

| 5 | ND | ND | >300 | 61 |

| 6 | ND | ND | >300 | 53 |

| 7 | ND | ND | >300 | 62 |

| 8 | >50e | IA | >300 | 50 |

| 9 | ND | ND | >300 | 51 |

| 10 | ND | ND | >300 | 53 |

| 11 | ND | ND | >300 | 55 |

| 12 | ND | ND | >300 | 62 |

| 13 | ND | ND | 176±8 | 62 |

| 14 | ND | ND | >300 | 51 |

| 15 | ND | ND | >300 | 51 |

| 16 | ND | ND | >300 | 57 |

| 17 | 22±2e | 4.7 | 180±5 | 57 |

| 18 | 11±2 | 5.0 | 149±7 | 60 |

| 19 | 8±1 | 5.1 | 146±11 | 63 |

| 20 | 12±3 | 4.9 | >300 | 60 |

| 21 | 10±2 | 5.0 | >300 | 64 |

| 22 | 9±2 | 5.1 | 170±12 | 69 |

| 23 | 9±1 | 5.1 | 117±6 | 58 |

| 24 | 11±1 | 5.0 | 189±28 | 60 |

| 25 | >50 | IA | >300 | 61 |

| 26 | >50f | IA | >300 | 57 |

| 27 | >50f | IA | 266±9 | 60 |

| 28 | >50f | IA | 100±4 | 57 |

| 29 | 2.4±0.6e | 5.6 | 57±10 | 62 |

| 30 | 5.6±0.4f | 5.2 | 53±8 | 60 |

| 31 | 7.6±0.3f | 5.1 | 41±9 | 43 |

| 32 | 12±1f | 4.9 | 39±11 | 38 |

| 33 | >50 | IA | 51±14 | 63 |

| 34 | 7±1 | 5.2 | 41±1 | 66 |

| 35 | >50 | IA | 41±15 | 66 |

| 36 | 5.0±0.4 | 5.3 | 117±7 | 68 |

| 37 | 4.3±0.1 | 5.4 | 63±7 | 70 |

| 38 | 19±2 | 4.7 | 34±3 | 59 |

| 39 | 7.5±0.6 | 5.1 | 33±3 | 62 |

| 40 | 6±1 | 5.2 | 85±9 | 63 |

| 41 | 19±2 | 4.7 | >300 | 51 |

| 42 | 17±1 | 4.8 | 268±5 | 54 |

| 43 | 40±8 | 4.4 | >300 | 54 |

| 44 | 41±12 | 4.4 | >300 | 52 |

| 45 | >50 | IA | 38±10 | 37 |

| 46 | 18±6 | 4.8 | 74±8 | 55 |

| 47 | 8±1 | 5.1 | 71±12 | 63 |

| PI(3,4,5)P3 | 0.5±0.1f | 6.3 | ND | 119 |

| DPIEL | 1.6±0.2f | 5.8 | ND | 40 |

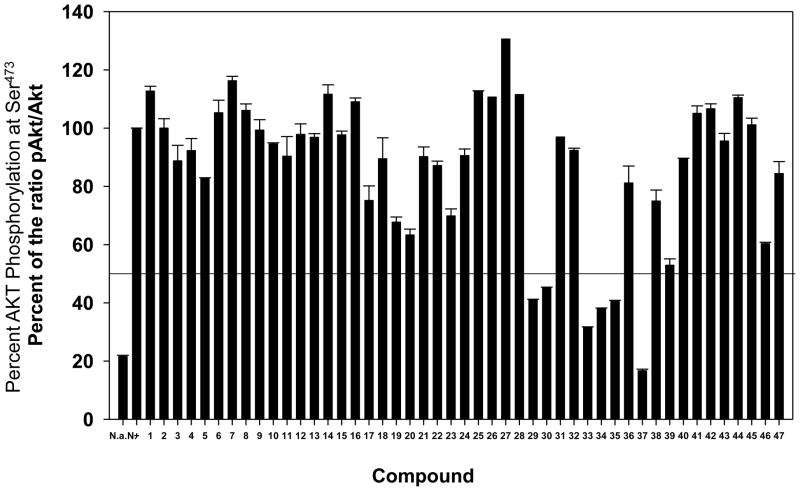

Figure 2.

Extent of AKT phosphorylation at Ser473 in the presence of compounds 1–47 at 10 μM.

Following binding experiments, cellular assays were conducted: cellular proliferation (see Table 2, IC50 values) and inhibition of AKT activation in BxPC3 cells (Figure 2) were measured in the presence of compounds 1–47. Cellular activity tracks reasonably well with the Ki values. Compounds 1–16 with an amino or acetamido substituent at R4 were inactive. Several compounds bearing a decanamido substituent at R4 showed some activity in one or both assays (e.g., 17, 19, 20, and 23). The best activities were exhibited by compounds 29, 30, 33–35, and 37 that possess C12H25 or C14H29 substituents at R4 and in some cases an R1 substituent at position 5 of the thiadiazole ring. Replacement of the R4 alkyl substituent by phenyl or a PEG amide gave inactive compounds 41–44. Interestingly, compound 45, with a phenyl substituent in place of the thiadiazole ring, did not inhibit phosphorylation of AKT at Ser473 but did inhibit BxPC-3 cell proliferation. The position of the aliphatic chain also mattered, as compounds 46 and 47 with dodecyl groups ortho and meta to the sulfonamide did not greatly inhibit the production of pAKT but did inhibit BxPC-3 cell proliferation.

3.3 Computational Modeling

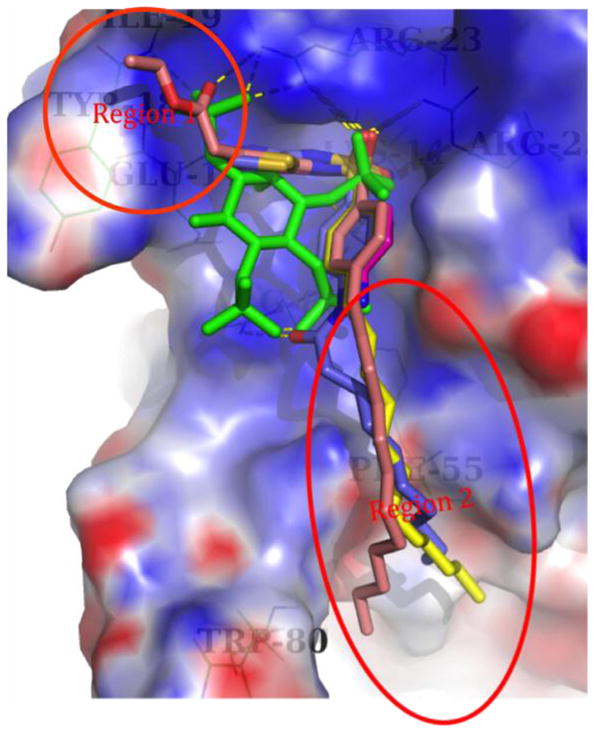

Molecular docking was used to investigate the binding of compounds 1–47 to the AKT PH domain. The best docking pose of each compound was selected according to the GOLD docking scores, the populations of the pose clusters, and their interactions with the binding pocket. For the purposes of this discussion, compounds 1, 17, 29, and 37 were selected to represent molecules in different chemical subgroups based on the substituent present at position R4. The best docking poses of these four molecules and of inositol(1,3,4,5)tetraphosphate (IP4) with the AKT PH domain are illustrated in Figure 3. In each case, the sulfonamide group interacts with Arg23, Arg25, and Lys14 in a manner similar to the best pose exhibited by compound 1.28 Compounds 2–7 and 8–16 bear amino and acetamido groups at R4, respectively, and variable substitution at R1. For the most part, these modifications did not result in large changes in the GOLD docking scores (see Table 2). Increasing the length of the carboxamide chain at R4 by replacement of the acetamido group with a decanamido group, as in compounds 17–25, improved the GOLD docking scores by an average of 7. This is consistent with the greater activity of these compounds as evidenced by the measured Ki values (Table 2).

Figure 3.

The best GOLD docking poses for IP4 (green), 1 (magenta), 17 (blue), 29 (yellow), and 37 (salmon). The dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds, and the electrostatic surface is for the protein. The circled regions are those with synthetic modifications.

Compound 29 is representative of the set of compounds 26–32 that possess alkyl substituents of varying length at R4. As depicted in Figure 3, the nitrogen atoms of the thiadiazole ring of 29 form hydrogen bonds with residue Glu17. The dodecyl chain extends from the main binding pocket to the protein surface, where it appears to interact with the hydrophobic residue Phe55. Shorter chains, as in 26, do not reach Phe55, thus weakening the binding. Based on our docking studies, the presence of a too-long chain, as in 31 and 32, changes the binding pose of the thiadiazole and sulfonamide moieties (not depicted). Compounds 29 and 30 that possess alkyl chains of optimal length (C12H25 and C14H29, respectively) exhibit stronger binding, as suggested by GOLD docking scores and confirmed by experimental observations (see Table 2).

As with 29, compounds 33–40 bear an optimal C12H25 chain at R4, and in addition, a substituent R1 on the thiadiazole ring. The R1 substituents range from nonpolar alkyl groups that vary in size, to more polar substituents containing carboxylic acid, carboxylate ester, and sulfonamide groups. The more polar groups were expected to mimic the phosphate at C-1 of PI(3,4,5)P3 and possibly interact with Arg23. Most of the compounds in this series exhibited relatively high GOLD docking scores (60–70) as well as measurable to good Ki values in an SPR-based competitive binding assay. For example, compounds 36 and 37, which bear carboxymethyl and 2-ethoxy-2-oxoethyl substituents at R1, possess two of the three highest GOLD docking scores obtained and Ki values of 5.0 and 4.3 μM, respectively, indicative of relatively strong competitive binding against PI(3,4,5)P3. The best binding poses of these compounds exhibit protein-small molecule interactions similar to those of 29 and also interact with Arg23 via the carbonyl moiety of the R1 substituent. The ethoxy group of 37 also exhibits hydrophobic interactions with Tyr18 and Ile19.

Structural modifications as in compounds 41–45 were detrimental to binding. Movement of the C12H25 chain from the para position (compound 29) to the ortho (46) or meta (47) positions also decreased the GOLD docking scores and experimentally measured Ki values.

In order to improve our inhibitor design capabilities, the flexibility of the PH domain is under study using molecular dynamics and normal mode analysis.36 By examining both backbone and side chain flexibility, we have found that docking predictions using the apo- structure produced results similar to those using more complex structures. In the present case of the AKT PH domain, 12 ns molecular dynamics following rigid docking demonstrated that accounting for protein flexibility did not improve the docking results significantly. The compound 29-PH domain complex was relatively stable, more or less staying bound in the original docked conformation except for the very end of the alkyl tail (see Supplementary Data for a dynamics movie). This suggests our approach to docking ligands into a rigid AKT PH domain structure virtual screening for targets for which complex crystal structures are unavailable has validity, in particular for this series of compounds related to 29.37

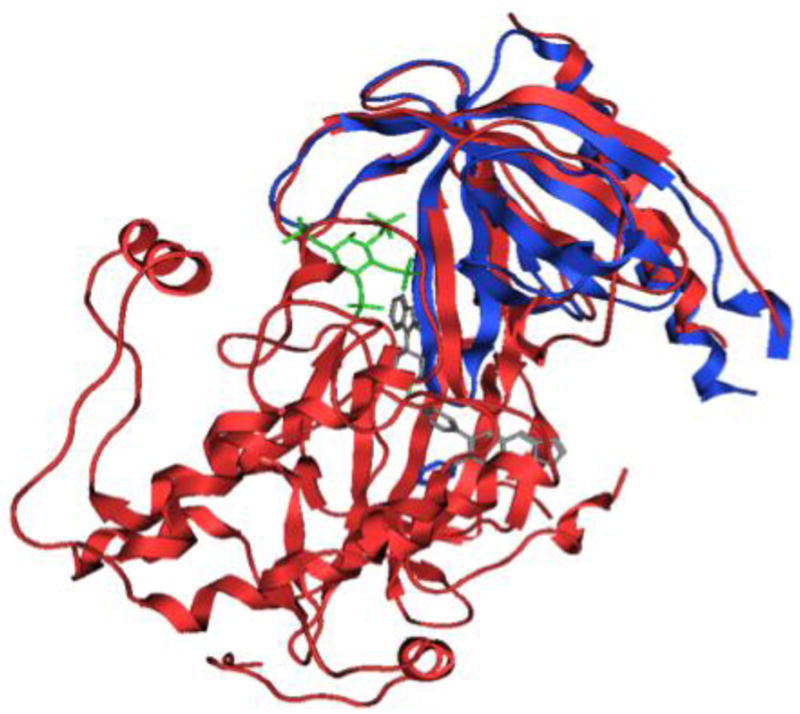

The availability of the crystal structure of the AKT kinase-PH domain with allosteric inhibitors provides additional understanding of this system.38 Structural alignment with the IP4-PH domain complex indicates that only the far side of loop 3–4 showed a significant difference and the kinase domain disrupts the phospholipid binding site of the PH domain (Figure 4). Therefore our inhibitors will not bind to this state of the PH domain.

Figure 4.

Structural alignment of AKT kinase-PH domain (PDB code 3O96, see reference 38) and PH domain (PDB code 1UNQ, see reference 37). Blue Ribbons: 1UNQ. Green sticks: PI(3,4,5)P3 from 1UNQ. Red Ribbons: 3O96. Grey sticks: inhibitor VIII from 3O96.

4. Discussion

In recent years, we identified a family of sulfonamides as being AKT inhibitors based on their direct binding to the PH domain and their cellular and in vivo activities.16, 25–27 Although there have been other efforts to develop AKT PH domain inhibitors, few SAR studies based on lead compounds and few studies where antitumor properties have been demonstrated in animals have appeared.18, 23, 39–42 The present study represents the first large SAR study on sulfonamide AKT PH domain inhibitors.

Based on docking of 1 to the PH domain of AKT, analogs 2–47 were designed, synthesized, tested for binding using an SPR-based assay, and for cellular activity. Modeling suggested that modification at position R4 would not disturb the best binding mode of 1 since R4 points away from the PI(3,4,5)P3 binding pocket (Figure 3). Compounds with small groups at R4, including 1–7 (R1 variable, R2 = R3 = H, R4 = NH2), 8–16 (R1 variable, R2 = R3 = H, R4 = acetamido), and 26–28 (R1 = R2 = R3 = H, R4 = C4-C8 alkyl chain) do not bind significantly to the AKT PH domain as determined by SPR measurements of competitive binding against PI(3,4,5)P3. Some compounds with longer amide-derived substituents at R4 (decanamides 17–24 and PEG-amide 44) exhibited the ability to inhibit PI(3,4,5)P3 binding (Ki < 50 μM), but at best weak cellular activity. SAR analysis also suggested that compounds with an aliphatic chain of the appropriate length at R4 (e.g., 29 and 30) exhibited the ability to inhibit PI(3,4,5)P3 binding (Ki) and good cellular activity as measured by inhibition of AKT phosphorylation and a cell survival assay using BxPC3 cells. However, the need to employ both binding and in vitro assays was underscored by the observation that compounds 31 and 32 bearing C16H33 and C18H37 chains, respectively, at R4, exhibited low μM values of Ki and the lowest IC50 values in the cell survival assay, but had little effect on AKT activity, as measured by the pAKT/AKT ratio. In addition, replacement of the thiadiazole ring of 29 with a phenyl ring (compound 45) decreased the Ki value, and 45 did not inhibit the production of pAKT, but did inhibit BxPC-3 cell proliferation. These observations suggest that cell-based activities depend not only on binding affinity, but also on other properties, such as cell permeability and compound solubility. In addition, off-target effects may occur and confound interpretation of the results. Off target effects of phosphatidylinositol ether lipid analogs (PIAs) led to the discovery that such compounds can activate a single isoform of p38, p38α, in vitro and in vivo.43 It was concluded that because p38α activation occurs in cancer cells after chemotherapy and in normal cells during inflammatory processes, activation of p38α by PIAs could contribute to the efficacy and/or toxicity of PIAs.

Modeling also suggested that the sulfonamide moieties of strongly bound compounds, such as 29, mimic the phosphate group at C-3 of PI(3,4,5)P3 by interacting with Arg23, Arg25, and Lys14 (see Figure 3). As PI(3,4,5)P3 also interacts with Tyr18, Ile19, and Arg86 through the C-1 phosphate, substituents were introduced at position R1 to mimic the C-1 phosphate. Compounds 18–25, 33–40, and 42–43 were of most interest in this regard, but exhibited Ki and IC50 values similar to those of the reference compounds bearing H at R1 (17, 29, and 41, respectively). Thus, substitution at R1 appears to be of lesser importance than was expected.

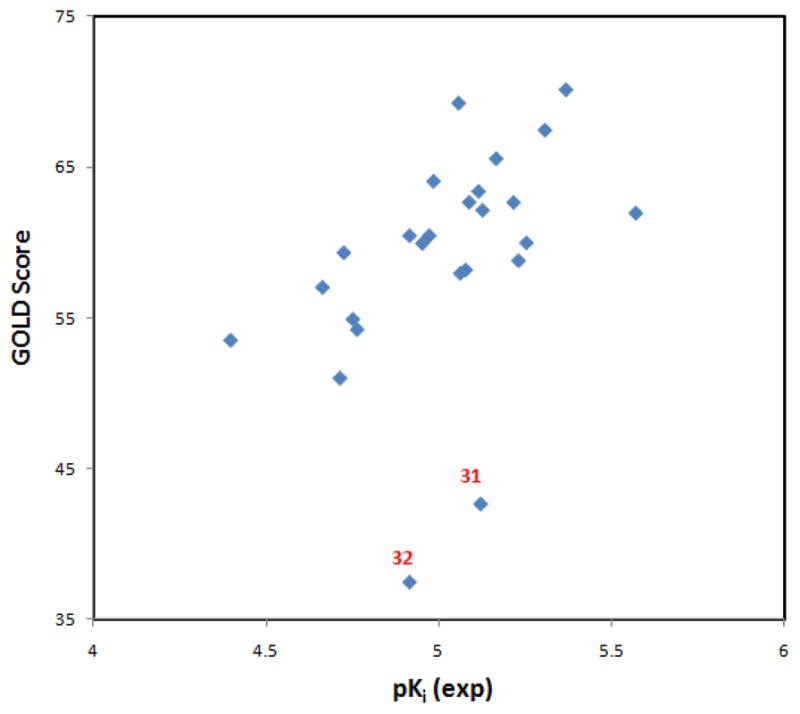

Although studies have shown that most of the current scoring functions in docking are of limited accuracy and the docking scores usually are not well correlated with experimentally measured binding affinities,35 in the present study a correlation between the GOLD docking scores and pKi (see Table 2) is apparent (Figure 5). Docking suggested that the two outliers, compounds 31 and 32, adopt alternate binding poses due to the steric problems caused by the too-long alkyl chains. This agreement between the GOLD docking scores and the experimentally determined pKi values supports our previous assertion that the combination of GOLD docking and GOLD scoring is appropriate for modeling this system.33

Figure 5.

The correlation between experimental pKi values and GOLD scores. Compounds 31 and 32 are outliers, suggesting their binding mode might be different from the other compounds.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants RO1 CA 061015 and P30 CA 23074 from the National Cancer Institute. SM was supported in part by the MGE@MSA fellowship and by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

Abbreviations

- AKT

protein kinase B

- β-ARK

beta-adrenergic receptor kinase

- CREB

cAMP response element-binding

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium

- DPIEL

deoxyphosphatidylinositol ether lipid

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HRMS

high resolution mass spectrum

- ILK

integrin-linked kinase

- IRS-1

insulin receptor substrate-1

- LRMS

low resolution mass spectrum

- mSOS

mammalian son-of-sevenless

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- PDPK1

3-phosphoinositide dependent protein kinase-1

- PH

pleckstrin homology

- PI

phosphoinositol

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PI(4

5)P2, phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate

- PI(3

4,5)P3, phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate

- RP HPLC

reversed phase high performance liquid chromatography

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- TLC

thin-layer chromatography

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Details of the synthesis and characterization of compounds 1–25 and 41–47 and the associate references.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Rebecchi MJ, Scarlata S. Ann Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1998;27:503. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemmon MA. Biochem Soc Symp. 2007;74:81. doi: 10.1042/BSS0740081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park WS, Heo WD, Whalen JH, O’Rourke NA, Bryan HM, Meyer T, Teruel MN. MolCell. 2008;30:381. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicholson KM, Anderson NG. Cell Signal. 2002;14:381. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao L, Vogt PK. Oncogene. 2008;27:5486. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheid MP, Woodgett JR. FEBS Lett. 2003;546:108. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00562-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alessi DR, James SR, Downes CP, Holmes AB, Gaffney PRJ, Reese CB, Cohen P. Curr Biol. 1997;7:261. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Science. 2005;307:1098. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du K, Montminy M. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung J, Grammer TC, Lemon KP, Kazlauskas A, Blenis J. Nature. 1994;370:71. doi: 10.1038/370071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Weeren PC, de Bruyn KMT, de Vries-Smits AMM, van Lint J, Burgering BMT. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhong H, Chiles K, Feldser D, Laughner E, Hanrahan C, Georgescu MM, Simons JW, Semenza GL. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Q. Exp Opin Ther Pat. 2007;17:1077.and references cited therein

- 14.Lindsley CW. Curr Top Med Chem. 2010;10:458. doi: 10.2174/156802610790980602.and references cited therein.

- 15.Barnett SF, Defeo-Jones D, Fu S, Hancock PJ, Haskell KM, Jones RE, Kahana JA, Kral AM, Leander K, Lee LL, Malinowski J, McAvoy EM, Nahas DD, Robinson RG, Huber HE. Biochem J. 2005;385:399. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meuillet EJ, Mahadevan D, Vankayalapati H, Berggren M, Williams R, Coon A, Kozikowski AP, Powis G. Mol Cancer Therap. 2003;2:389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meuillet EJ, Ihle N, Baker AF, Gard JM, Stamper C, Williams R, Coon A, Mahadevan D, George BL, Kirkpatrick L, Powis G. Oncol Res. 2004;14:513. doi: 10.3727/0965040042380487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castillo SS, Brognard J, Petukhov PA, Zhang C, Tsurutani J, Granville CA, Li M, Jung M, West KA, Gills JG, Kozikowski AP, Dennis PA. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2782. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mills SJ, Vandeput F, Trusselle MN, Safrany ST, Erneux C, Potter BVL. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:1757. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang BX, Kim HY. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009;20:1504. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ropars V, Barthe P, Wang CS, Chen W, Tzou DLM, Descours A, Martin L, Noguchi M, Auguin D, Roumestand C. The Open Spectroscopy Journal. 2009;3:65. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fyrst H, Oskouian B, Bandhuvula P, Gong Y, Byun HS, Bittman R, Lee AR, Saba JD. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9457. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim D, Sun M, He L, Zhou QH, Chen J, Sun XM, Bepler G, Sebti SM, Cheng JQ. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.094060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24.Estrada AC, Syrovets T, Pitterle K, Lunov O, Büchele B, Schimana-Pfeifer J, Schmidt T, Morad SAF, Simmet T. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:378. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.060475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahadevan D, Powis G, Mash EA, George B, Gokhale VM, Zhang S, Shakalya K, Du-Cuny L, Berggren M, Ali MA, Jana U, Ihle N, Moses S, Franklin C, Narayan S, Shirahatti N, Meuillet EJ. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2621. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moses SA, Ali MA, Zuohe S, Du-Cuny L, Zhou LL, Lemos R, Ihle N, Skillman AG, Zhang S, Mash EA, Powis G, Meuillet EJ. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5073. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meuillet EJ, Zuohe S, Lemos R, Ihle N, Kingston J, Watkins R, Moses SA, Zhang S, Du-Cuny L, Herbst R, Jacoby JJ, Zhou LL, Ahad AM, Mash EA, Kirkpatrick DL, Powis G. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:706. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neubert ME, Laskos SJ, Jr, Griffith RF, Stahl ME, Maurer LJ. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst. 1979;54:221. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiseleva VV, Gakh AA, Fainzil’berg AA. Izvestiya Akademii Nauk SSSR, Seriya Khimicheskaya. 1990;9:2075.This starting material is available from ChemBridge Corporation

- 30.Thiel W, Mayer R. J Prakt Chem. 1990;332:55. This starting material is available from Oakwood Products.

- 31.Heindl J, Schröder E, Kelm H-W. Eur J Med Chem. 1975;10:121.This starting material is available from UkrOrgSynthesis.

- 32.Lee A-R, Lee H-F, Huang W-H, Chiang C-H. Zhonghua Yaoxue Zazhi. 1993;45:115. This starting material is available from Ramidus AB.

- 33.Du-Cuny L, Song Z, Moses S, Powis G, Mash EA, Meuillet EJ, Zhang S. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:6983. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.GOLD [3.2] CCDC; Cambridge, UK: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warren GL, Andrews CW, Capelli AM, Clarke B, LaLonde J, Lambert MH, Lindvall M, Nevins N, Semus SF, Senger S, Tedesco G, Wall ID, Woolven JM, Peishoff CE, Head MS. J Med Chem. 2006;49:5912. doi: 10.1021/jm050362n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran HT, Zhang S. Manuscript in preparation [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milburn CC, Deak M, Kelly SM, Price NC, Alessi DR, van Aalten DMF. Biochem J. 2003;375:531. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu WI, Voegtli WC, Sturgis HL, Dizon FP, Vigers GPA, Brandhuber BJ. Plos ONE. 2010;5:e12913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miao B, Skidan I, Yang J, Lugovskoy A, Reibarkh M, Long K, Brazell T, Durugkar KA, Maki J, Ramana CV, Schaffhausen B, Wagner G, Torchilin V, Yuan J, Degterev A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004522107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang L, Dan HC, Sun M, Liu Q, Sun XM, Feldman RI, Hamilton AD, Polokoff M, Nicosia SV, Herlyn M, Sebti SM, Cheng JQ. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4394. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barnett SF, Bilodeau MT, Lindsley CW. Curr Top Med Chem. 2005;5:109. doi: 10.2174/1568026053507714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berrie CP, Falasca M. FASEB J. 2000;14:2618. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0096hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gills JJ, Castillo SS, Zhang C, Petukhov PA, Memmott RM, Hollingshead M, Warfel N, Han J, Kozikowski AP, Dennis PA. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.