Abstract

Objectives

To prospectively determine the feasibility of diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) with fibre tractography as a tool for the three-dimensional (3D) visualisation of normal pelvic floor anatomy.

Methods

Five young female nulliparous subjects (mean age 28 ± 3 years) underwent DTI at 3.0T. Two-dimensional diffusion-weighted axial spin-echo echo-planar (SP-EPI) pulse sequence of the pelvic floor was performed, with additional T2-TSE multiplanar sequences for anatomical reference. Fibre tractography for visualisation of predefined pelvic floor and pelvic wall muscles was performed offline by two observers, applying a consensus method. Three eigenvalues (λ1, λ2, λ3), fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD) were calculated from the fibre trajectories.

Results

In all subjects fibre tractography resulted in a satisfactory anatomical representation of the pubovisceral muscle, perineal body, anal - and urethral sphincter complex and internal obturator muscle. Mean FA values ranged from 0.23 ± 0.02 to 0.30 ± 0.04, MD values from 1.30 ± 0.08 to 1.73 ± 0.12 × 10−³ mm²/s. Muscular structures in the superficial layer of the pelvic floor could not be satisfactorily identified.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the feasibility of visualising the complex three-dimensional pelvic floor architecture using 3T-DTI with fibre tractography. DTI of the deep female pelvic floor may provide new insights into pelvic floor disorders.

Keywords: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI), Pelvic floor, Fibre tractography, Anatomy

Introduction

The female pelvic floor has a multilayered complex anatomy and includes several closely aligned muscles [1]. For imaging work-up of pelvic floor dysfunction, either evacuation proctography [2], transperineal ultrasound [3] or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used [4–6]. MRI has the advantage that no ionising radiation is employed and offers a high contrast resolution multiplanar examination with a detailed demonstration of the pelvic floor anatomy. To date, MRI has been demonstrated to be valuable in the characterisation of pelvic floor muscle defects [7, 8]. However, the complexity of the pelvic floor anatomy does not make either the interpretation of these examinations or the communication of the results straightforward. This generally concerns the presence of muscular defects and altered signal intensity (e.g. scar tissue).

In vivo diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has emerged as a unique non-invasive tool to describe the directionality of the internal microstructure within anisotropic tissues [9]. For anisotropic tissues, it is known that the diffusion of water is higher in the length of an internal microstructure and conversely, diffusion will be more restricted perpendicular to this direction. The directional dependence of water diffusion in tissue can be described by a three-dimensional (3D) diffusion tensor for each voxel. By combining the diffusion tensor data from multiple voxels, fibre tracts can be reconstructed that correlate with the principal diffusion direction of water molecules in a tissue microstructure [10]. This can provide important information about the tissue’s architectural organisation that cannot be extrapolated from conventional MRI techniques.

Thus far, MR- or fibre tractography has been studied extensively in order to visualise and characterise the normal and diseased cerebral and spinal white matter tracts [11], and to a lesser extent the fibre orientation of striated skeletal muscle [12, 13]. The latter is mostly limited to sizable muscles (muscle groups) of the upper and lower extremity, thereby avoiding motion-related artefacts and complex multidirectional anatomy. Demonstration of the normal pelvic floor muscular anatomy is more challenging and if this were feasible with DTI it might prove valuable in evaluating pelvic floor defects.

The aim of this work was to investigate the feasibility of visualising the normal pelvic floor musculature in healthy female nullipara subjects using DTI at 3.0 T. In addition, a quantitative description of the different muscles was performed by calculating the mean eigenvalues (λ1, λ2, λ3) and derived parameters (fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD)) for isolated muscles.

Material and methods

Study population

In this prospective pilot study, five healthy nullipara women volunteered to participate in this study (mean age 28 SD ± 3 years). Exclusion criteria for participating were history of pregnancy, any (symptom of) pelvic floor disease and/or previous pelvic surgery. Other exclusion criteria were (relative) contraindications to undergoing MRI; pacemakers, claustrophobia and pregnancy.

In order to exclude pelvic floor dysfunction, subjects were subjected to composed standardised questionnaires, including Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI), Defecation Distress Inventory (DDI) and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ) [14, 15]. This study was approved by the institutional review board. All subjects gave written informed consent.

MRI data acquisition

Magnetic resonance imaging was performed using 3.0T MRI (Intera, Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands). To allow coverage of the entire pelvic area a 6-channel surface coil was used, with subjects positioned in the supine position with the legs parallel, lightly flexed. Subjects were asked to empty the bladder before the examination. No contrast agent was administered in the bladder, urethra, vagina or rectum.

The MRI protocol comprised three sequences: static T1-weighted imaging (Turbo Spin Echo (TSE), field of view (FOV): 200 × 200 mm2, matrix: 400 × 400, slice thickness: 5 mm, slices: 20, TR/TE: 600/10 ms),T2-weighted imaging (FOV: 200 × 200 mm2, matrix: 400 × 400, slice thickness: 5 mm, slices: 20, TR/TE: 1560/70 ms) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) (Spin Echo- Echo- Planar-Imaging (SE-EPI), FOV: 200 × 200 mm2, matrix: 80 × 80 with 112 × 112 reconstructed matrix, slice thickness: 5 mm, slices: 20, 32 diffusion-weighed directions, TR/TE: 3250/48 ms, NSA: 2, b = 400 s/mm2, Spectral Adiabatic Inversion Recovery (SPAIR) for fat suppression, imaging time: 3 min 52 s). The diffusion-weighted images were registered to their unweighted b = 0 s/mm2 images using Philips software. Non-angulated T1-weighted TSE and DTI were performed in the axial plane. Non-angulated T2-weighted sequences of the pelvis were obtained in axial, sagittal and coronal orientations for anatomical reference.

Image quality of the obtained T1w and T2w sequences of all subjects, was analysed by 2 physicists (MF, AN) who scored image quality regarding the presence of artefacts. DTI datasets were assessed regarding the presence of distortions due to field heterogeneity.

Data analyses

Fibre tractography was performed offline using a dedicated software program (DTITool, Biomedical Image Analysis group, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, the Netherlands [16]). All data sets were independently analysed and measurements were performed by two observers (FZ, MP). After the initial independent analyses, the fibre tracking results were discussed by the two observers and modified if necessary, applying a consensus reading method. Both observer 1 (FZ, a third-year resident in radiology with an additional 3-year experience as a teaching assistant at the department of Anatomy and Embryology, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam) and observer 2 (MP, a second-year PhD student), were taught in the anatomy of the pelvic floor before analysis by an abdominal radiologist (JS) with extensive experience in MRI of the pelvic floor (>1500 examinations), including specific research into the MR anatomy of the pelvic floor. To determine whether fibre orientation and muscle shape were an adequate representation of the expected anatomical appearance, the findings were rated as satisfactory or non-satisfactory. These final findings were used for quantitative analysis.

The muscular structures of interest were: pubovisceral muscle; superficial transverse perinea, bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernosus muscle and the fibromuscular perineal body [1]. Also, special interest was focused on the muscular components of both the anal canal and urethral support, i.e. anal sphincter and the urethral sphincter complex. In addition, measurements were performed to track the major striated muscular component of the pelvic wall, i.e. the internal obturator muscle.

ROI selection

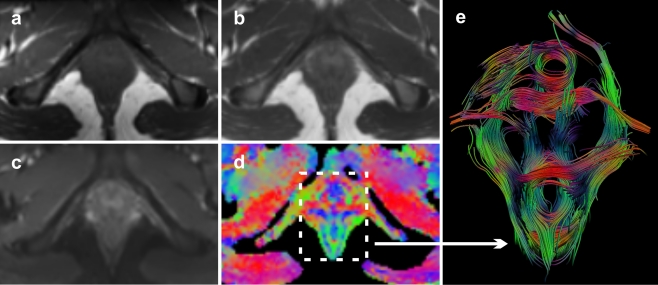

To allow the three-dimensional visualisation of the predefined muscles, a seed region of interest (ROI) in outline was manually drawn in the axial, coronal and/or sagittal planes on the resulting coloured FA map at the site where the course of the muscle could be expected. On the FA map, the per-voxel absolute vector values were colour-coded: red (medio-lateral direction), blue (cranio-caudal direction) and green (antero-posterior direction) (Fig. 1). The corresponding T2w anatomical series was used for anatomical reference. Based on the initial fibre tracking results the seeding contour was manually adjusted. If the total extent of the muscle was insufficiently identified with a single seeding ROI, additional ROIs were appended. Overall, fibre tracking was automatically terminated if one of three conditions was met: 1) fibre length > 100 mm; 2) FA threshold < 0.1; 3) fibre angle > 10°/step. In the case of small and/or circular (fibro) muscular structures (i.e. perineal body, anal sphincter and urethral sphincter complex), fibre tracking stop criteria were adjusted to fibre angle > 15°/step and fibre length > 40 mm, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Axial T1-weighted image (a), T2-weighted image (b), b = 0 image (c) and corresponding FA map (d) of the pelvic floor of a 24-year old healthy nulliparous female subject. FA and direction map with per-voxel colour-coded vector values: red (right-left direction), green (antero-posterior direction); blue (cranio-caudal direction). With the application of whole volume seeding, present three dimensional (3D) fibre trajectories provide a comprehensive overview of the complex pelvic floor anatomy (caudal view) (e)

DTI parameters

For each muscle five DTI parameters were automatically calculated, the three eigenvalues (λ1, λ2 and λ3), the mean diffusivity (MD), and the fractional anisotropy (FA), according to (1) and (2) (D = diffusion tensor):

|

1 |

|

2 |

For each muscle or muscle group the DTI parameters were calculated at multiple points per fibre along the fibre tracts. The parameters were considered as normal distributed data. From these data points the mean value for each of the parameters was calculated. Per-muscle data for five subjects were combined and were expressed as mean value ± standard deviation (SD).

Results

Based on the composed standardised questionnaires, none of the participating female subjects experienced any prolapse, micturition and/or defecation symptoms. Image quality of the obtained T1w, T2w and DTI datasets proved robust, and no influencing artefacts and/or distortions were detected.

Fibre-tracking resulted in a satisfactory representation of the global muscle morphology and fibre orientation for the following predefined pelvic muscular structures: pubovisceral muscle (Fig. 2), perineal body, anal sphincter complex (Fig. 3), urethral sphincter complex (Fig. 4) and internal obturator muscle (Fig. 5) in all five female volunteers.

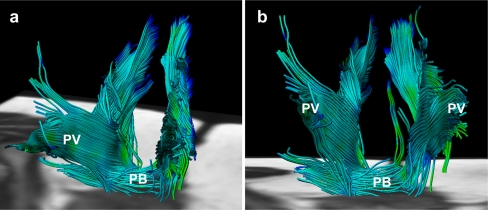

Fig. 2.

Fibre tractography demonstrates the complex, multidirectional organisation of the different pubovisceral (PV) muscle components in a 28-year old female subject in both oblique-anterior (a) and anterior-posterior view (b). At the bottom of the pelvic floor transverse orientation of the fibre tracts are displayed matching the perineal body (PB)

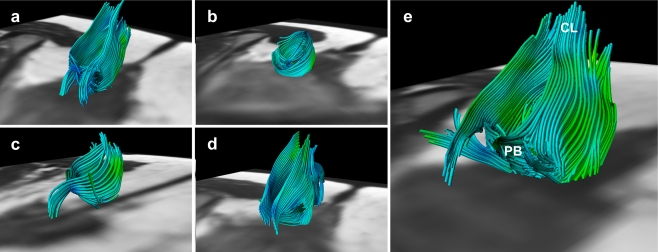

Fig. 3.

Fibre trajectories representing the anal sphincter complex in all five female subjects; 28 years, 32 years, 24 years, 27 years and 31 years of age, respectively (a–e). Not all extrapolated fibre trajectories, matching the appearance of the anal sphincter complex, were perfectly circularly orientated. This might be attributed to both the predefined fibre angle cut-off point and the potential inaccurate fibre tractography based on signal originating from various muscles and ligamentous structures converging and interweaving in this area (e.g. perineal body (PB) and coccygeal ligament (CL)) (e)

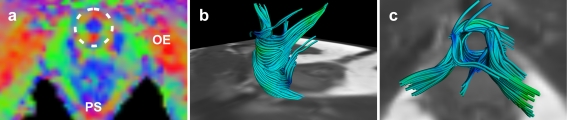

Fig. 4.

Transverse colour coded FA-map image of the inferior pelvic floor of a 31-year old nulliparous female subject (a). Several anatomical structures are depicted on this level based on the colour code: external obturator muscle (OE) and puborectal sling (PS). Similar to the anal sphincter complex, the vector orientation on the level of the urethral sphincter was medio-laterally (red) orientated at the anterior and posterior borders, and antero-posteriorly (green) orientated at the lateral border in all subjects, as an indication of the circular organisation of the structure (dotted circle) (a). Fibre trajectories reflecting the urethral sphincter complex with a anterolateral (b) and cranial view (c)

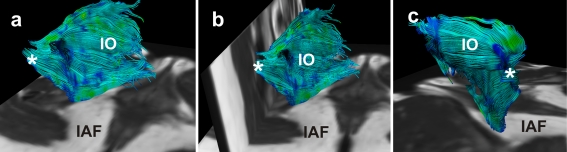

Fig. 5.

Fibre trajectories as a representation of the internal obturator muscle (IO) from a postero-medial (a), posterior (b) and postero-lateral view (c) in a 27-year old female subject. The flat muscle shape is satisfactory represented; the muscle is medio-inferiorly bounded by the ischio-anal fossa (IAF). Fibre tracks converge posteriorly and bend laterally into the greater sciatic foramen (*)

Although for each identified muscle the corresponding origin and insertion could not be clearly identified, all fibres were positioned within the expected muscle boundaries as perceptible on corresponding anatomical T2w series. At the level of both the anal canal and urethral sphincter complex, we were able to detect circularly orientated fibre trajectories (Figs. 1, 3 and 4 ). No supplementary categorisation in muscular components (i.e. smooth muscle vs. striated muscle) could be stratified from the obtained fibre trajectories.

The bulbospongiosus muscle, ischiocavernosus muscle and superficial transverse perineal muscle could not or could only partially be tracked in the available datasets and were therefore rated as unsatisfactory representations in all 5 volunteers. Accordingly, no parameters were calculated for these muscular structures.

Per-group mean values of fractional anisotropy (FA) for the different muscles were comparable and ranged from 0.23 ± 0.02 to 0.30 ± 0.04. Lowest FA values were found for the urethral sphincter and highest for the anal sphincter complex. Lowest in-group variability was found for the internal obturator muscle (SD = ± 0.01). Highest per-group variability in mean diffusivity (MD) and the three eigenvalues (λ1, λ2 and λ3) was found for the pubovisceral muscle (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean DTI values ± SD were calculated from five female subjects for each muscle

| FA | MD * | λ1 * | λ2 * | λ3 * | # pointsa | # fibresb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anal sphincter | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 1.30 ± 0.08 | 1.70 ± 0.08 | 1.24 ± 0.08 | 0.95 ± 0.11 | 22566 | 457 |

| Urethral sphincter | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 1.73 ± 0.12 | 2.15 ± 0.17 | 1.69 ± 0.11 | 1.36 ± 0.10 | 9241 | 174 |

| Pubovisceral muscle | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 1.49 ± 0.47 | 1.89 ± 0.51 | 1.45 ± 0.47 | 1.12 ± 0.43 | 60550 | 1035 |

| Perineal body | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 1.32 ± 0.19 | 1.67 ± 0.17 | 1.28 ± 0.21 | 0.99 ± 0.20 | 3896 | 97 |

| Internal obturator muscle | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 1.51 ± 0.11 | 1.93 ± 0.13 | 1.43 ± 0.09 | 1.16 ± 0.10 | 89330 | 888 |

FA Fractional Anisotropy; MD Mean Diffusivity

* MD, λ1, λ2, λ3 are in units of [×10−³ mm²/s]

aRefers to the mean number of points from which DTI parameters are calculated

bRefers to the mean number of fibres per isolated muscle

Discussion

In this feasibility study we obtained three-dimensional fibre trajectories of the female pelvic floor and wall muscles, which match the global appearance of the pubovisceral muscle, perineal body, anal sphincter complex, urethral sphincter complex and internal obturator muscle based on fibre orientation, shape, size and location. Furthermore, the extrapolated objective microstructural parameters fitted within the range of values previously reported studying striated muscle diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) [10, 12, 13].

To date, studies assessing striated muscles by means of DTI are narrowed to mostly normal, perfectly geometrically arranged muscles in the muscle compartments of the lower extremity [10, 12]. By assessing the feasibility of DTI fibre-tracking of the muscular pelvic floor, we were confronted with a complex organisation of muscular structures, demonstrating a pennate architecture with indistinct boundaries regarding origin and insertion in close relation to adjacent pelvic viscera (e.g. bladder, vagina and rectum) [1]. Yet, we were able to collect data sets without notable distortions at SE-EPI and T2w-TSE sequences and no disturbing motion-related artefacts were observed in the five data sets.

Fibre tracts at the level of the anal- and urethral sphincter complex demonstrated a strong circular directionality in all five female subjects, which therefore was appreciated as a representation of both sphincter complexes. However, both urethral sphincter and anal sphincter constitute two important cylindrical muscular structures, i.e. smooth muscle inner layer (lissosphincter, internal sphincter, respectively) and striated muscle outer layer (rhabdosphincter, external sphincter, respectively) [1], which we were unable to discriminate. In the current literature, little is known about fibre tracking applied in smooth muscle cell structures, and one can question whether its anisotropic characteristics in DTI applications are similar to those of striated muscle. Because of such uncertainties, we have considered the fibre tracts as a representation of the cylindrical sphincter complex, rather than as a representation of striated sphincter alone.

The highest variability in mean diffusivity (MD) values was found for the pubovisceral muscle (1.49 ± 0.47 × 10−³ mm²/s) and might be attributed to the complex organisation of this muscle. The pubovisceral muscle encompasses several muscular components: the puboperineal/pubovaginal muscle, puboanal muscle and puborectal muscle [1]. Muscle fibres are orientated in different directions, are closely aligned and demarcations among the endopelvic fascia, intermuscular fat issue and neurovascular bundle are indistinct. The relatively wide ROIs used for data collection for this muscle might therefore be subjected to alterations in both fibre tracking and extrapolated parameters.

Muscular structures of the superficial layer of the pelvic floor (bulbospongiosus, ischiocavernosus and superficial transverse perineal muscle) could not be satisfactorily identified in the available datasets, although these muscles play a less important supportive role in pelvic floor dysfunction and are therefore are of less clinical importance [1]. Optimising the protocol and increasing resolution might solve present limitations for detecting these small superficial structures, but can also result in lower SNR which decreases the accuracy of fibre tractography and parameter estimation. Also, increasing the resolution would increase the echo train length of echo planar imaging (EPI) acquisition leading to more artefacts associated with EPI imaging, e.g. deformation due to field heterogeneities.

Owing to the relatively small dimensions of some of the pelvic muscles [1, 17], relative to the voxel dimensions (5 × 1.79 × 1.79 mm3), it was difficult to isolate individual small muscles. Voxels might contain signal originating from multiple muscles or both muscle and fat leading to partial volume effects, which could lead to inaccurate values for the DTI parameters and fibre tractography. As a fibre trajectory originating from a single muscle voxel connects to a subsequent voxel containing signal from a different muscle, the tract might continue its path in a different muscle to that in which it originated. Reduction of this partial volume effect can be accomplished by reducing the voxel size, which consequently decreases the signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs). Another option is to use high angular resolution diffusion imaging (HARDI) which is a novel post-processing technique that is able to describe multiple fibre directions in a single voxel [18].

Although fibre tractography in the pelvic region was proven feasible for most predefined muscular structures, several issues need improvement. The seeding of fibres is a time-consuming iterative manual process and is reported to be strongly user-dependent, which ultimately affects the output results [19]. For fibre tractography as a clinical tool this is not desirable.

This feasibility study has recognised limitations. The number of subjects studied was limited, but the consistent feasibility of DTI of the important pelvic floor structures shows the robustness of the technique. As variation in observed diffusion parameters in relation to age and gender have been reported [20], larger and more heterogeneously composed cohorts need to be evaluated in order to derive objective reference values for pelvic floor diffusion parameters. We included only female subjects of relatively young age and without symptoms in this feasibility study as we wanted to demonstrate the normal anatomy before considering studying patients. As pelvic floor dysfunction primarily concerns women, we limited our study to female subjects.

The current available musculoskeletal DTI tractography literature shows a rather large heterogeneity in reported diffusion parameter values. This heterogeneity might be attributed to the recognised user-dependent analytical methods to some degree [19]. From this perspective, the assessment of reproducibility (i.e. intra-observer and inter-observer variability) is essential in order to evaluate DTI with tractography for diagnostic purposes. This study was primarily aimed at assessing the feasibility of visualising the muscular anatomy of the pelvic floor and therefore reproducibility was not assessed.

In conclusion, 3T diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) with fibre tractography is a technically feasible method for the three-dimensional visualisation of the normal female muscular pelvic floor. The overall small SDs of the extrapolated fractional anisotropy (FA), the mean diffusivity (MD) values strongly suggest that we were able to reliably measure per-muscle DTI parameters in the pelvic area. In this pilot study we studied the normal anatomy in nulliparous women without previous pelvic trauma.

Research is needed to define the potential role of DTI and fibre tractography in demonstrating alterations in pelvic organ support in pelvic floor dysfunction, e.g. pelvic organ prolapse, paravaginal defects and urinary incontinence. Sizeable prospective case–control studies using this methodology are warranted in order to assess whether DTI might provide insights into pelvic floor dysfunction which are not appreciated on conventional magnetic resonance imaging . This may not only concern anatomical defects, but also assessment of differences in muscle fibre direction (i.e. eigenvectors) and measured diffusion parameters between normal and injured muscle tissue [21, 22].

Acknowledgments

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Stoker J, Wallner C. The anatomy of the pelvic floor and sphincters. In: Stoker J, Taylor S, De Lancey JOL, editors. Imaging pelvic floor disorders. New York: Springer Verlag; 2008. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maglinte DD, Bartram C. Dynamic imaging of posterior compartment pelvic floor dysfunction by evacuation proctography: techniques, indications, results and limitations. Eur J Radiol. 2007;61:454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majida M, Braekken IH, Umek W, Bø K, Saltyte Benth J, Ellstrøm Engh M. Interobserver repeatability of three- and four-dimensional transperineal ultrasound assessment of pelvic floor muscle anatomy and function. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;33:567–573. doi: 10.1002/uog.6351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyadzhyan L, Raman SS, Raz S. Role of static and dynamic MR imaging in surgical pelvic floor dysfunction. Radiographics. 2008;28:949–967. doi: 10.1148/rg.284075139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colaiacomo MC, Masselli G, Polettini E, Lanciotti S, Casciani E, Bertini L, Gualdi G. Dynamic MR imaging of the pelvic floor: a pictorial review. Radiographics. 2009;29:e35. doi: 10.1148/rg.e35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoker J, Rociu E, Bosch JL, Messelink EJ, van der Hulst VP, Groenendijk AG, Eijkemans MJ, Laméris JS. High-resolution endovaginal MR imaging in stress urinary incontinence. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:2031–2037. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-1855-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobben AC, Terra MP, Slors JF, Deutekom M, Gerhards MF, Beets-Tan RG, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. External anal sphincter defects in patients with fecal incontinence: comparison of endoanal MR imaging and endoanal US. Radiology. 2007;242:463–471. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2422051575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLancey JO, Kearney R, Chou Q, Speights S, Binno S (2003) The appearance of levator ani muscle abnormalities in magnetic resonance images after vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 101(1):46-53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Lansdown DA, Ding Z, Wadington M, Hornberger JL, Damon BM. Quantitative diffusion tensor MRI-based fiber tracking of human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:673–681. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00290.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinha U, Yao L. In vivo diffusion tensor imaging of human calf muscle. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;15:87–95. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi SJ, Lim KO, Monteiro I, Reisberg B. Diffusion tensor imaging of frontal white matter microstructure in early Alzheimer’s disease: a preliminary study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18:12–19. doi: 10.1177/0891988704271763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budzik JF, Le Thuc V, Demondion X, Morel M, Chechin D, Cotten A. In vivo MR tractography of thigh muscles using diffusion imaging: initial results. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:3079–3085. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0713-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Froeling M, Oudeman J, van den Berg S, Nicolay K, Maas M, Strijkers GJ, Drost MR, Nederveen AJ. Reproducibility of diffusion tensor imaging in human forearm muscles at 3.0 T in a clinical setting. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:1182–1190. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uebersax JS, Wyman JF, Shumaker SA, McClish DK, Fantl JA. Short forms to assess life quality and symptom distress for urinary incontinence in women: the incontinence impact questionnaire and the urogenital distress inventory. Neurourol Urodyn. 1995;14:131–139. doi: 10.1002/nau.1930140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Brummen HJ, Bruinse HW, van de Pol G, Heintz APM, van der Vaart CH. Defecatory symptoms during and after the first pregnancy: prevalences and associated factors. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:224–230. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1351-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vilanova A, Berenshot G, van de Pul C (2004) DTI Visualization with Streamsurfaces and Evenly-Spaced Volume Seeding. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the VisSym Joint Eurographics/IEEE TCVG Symposium on Visualization; Konstanz, Germany

- 17.Rociu E, Stoker J, Eijkemans MJ, Laméris JS. Normal anal sphincter anatomy and age- and sex-related variations at high-spatial-resolution endoanal MR imaging. Radiology. 2000;217:395–401. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.2.r00nv13395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuch DS, Reese TG, Wiegell MR, Wiegell MR, Makris N, Belliveau JW, Wedeen VJ. High angular resolution diffusion imaging reveals intravoxel white matter fiber heterogeneity. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:577–582. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brecheisen R, Vilanova A, Platel B, ter Haar Romeny B. Parameter sensitivity visualization for DTI fiber tracking. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph. 2009;15:1441–1448. doi: 10.1109/TVCG.2009.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khalil C, Budzik JF, Kermarrec E, Balbi V, Le Thuc V, Cotten A. Tractography of peripheral nerves and skeletal muscles. Eur J Radiol. 2010;76:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaraiskaya T, Kumbhare D, Noseworthy MD. Diffusion tensor imaging in evaluation of human skeletal muscle injury. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:402–408. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kan JH, Heemskerk AM, Ding Z, Gregory A, Mencio G, Spindler K, Damon BM. DTI-based muscle fibre tracking of the quadriceps mechanism in lateral patellar dislocation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29:663–670. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]