Abstract

Pericardial fat necrosis is an infrequent cause of acute chest pain and this can mimic acute myocardial infarction and acute pericarditis. We describe here a patient with the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of pericardial fat necrosis and this was correlated with the computed tomography (CT) findings. The MRI findings may be helpful for distinguishing pericardial fat necrosis from other causes of acute chest pain and from the fat-containing tumors in the cardiophrenic space of the anterior mediastinum.

Keywords: Pericardial fat, Fat necrosis, Magnetic resonance (MR)

INTRODUCTION

Pericardial fat necrosis is an uncommon cause of acute chest pain and this can mimic acute myocardial infarction and acute pericarditis (1). The main computed tomography (CT) features of pericardial fat necrosis are an encapsulated fatty lesion with dense strands and thickening of the adjacent pericardium (1). Together with acute chest pain, these findings form a triad that is indicative of a diagnosis of fat necrosis. To date, CT has been the method of choice to assess pericardial fat necrosis and other diseases that cause acute chest pain.

Fat necrosis that has occurred at various sites in the body has been detected using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (2, 3). In the English-language medical literature, the MRI findings of pericardial fat necrosis in two patients have been reported as fat-containing masses without contrast enhancement (1, 4).

To the best of our knowledge, our patient is the first reported case of acute pericardial fat necrosis as imaged using MRI with contrast enhancement.

CASE REPORT

A 39-year-old man was admitted to our hospital due to a 1-day episode of sharp and sudden pleuritic pain in his left anterior lower chest. The physical examination, the laboratory tests including the cardiac enzymes, the electrocardiography, a coronary angiogram to exclude coronary artery anomalies, the Holter monitoring and the thallium-201 myocardial scan were all normal. His height was 160 cm, his weight was 63 kg and he did not appear obese. Three months previously, he had experienced mild chest pain for one day. At that time, the pain subsided without treatment.

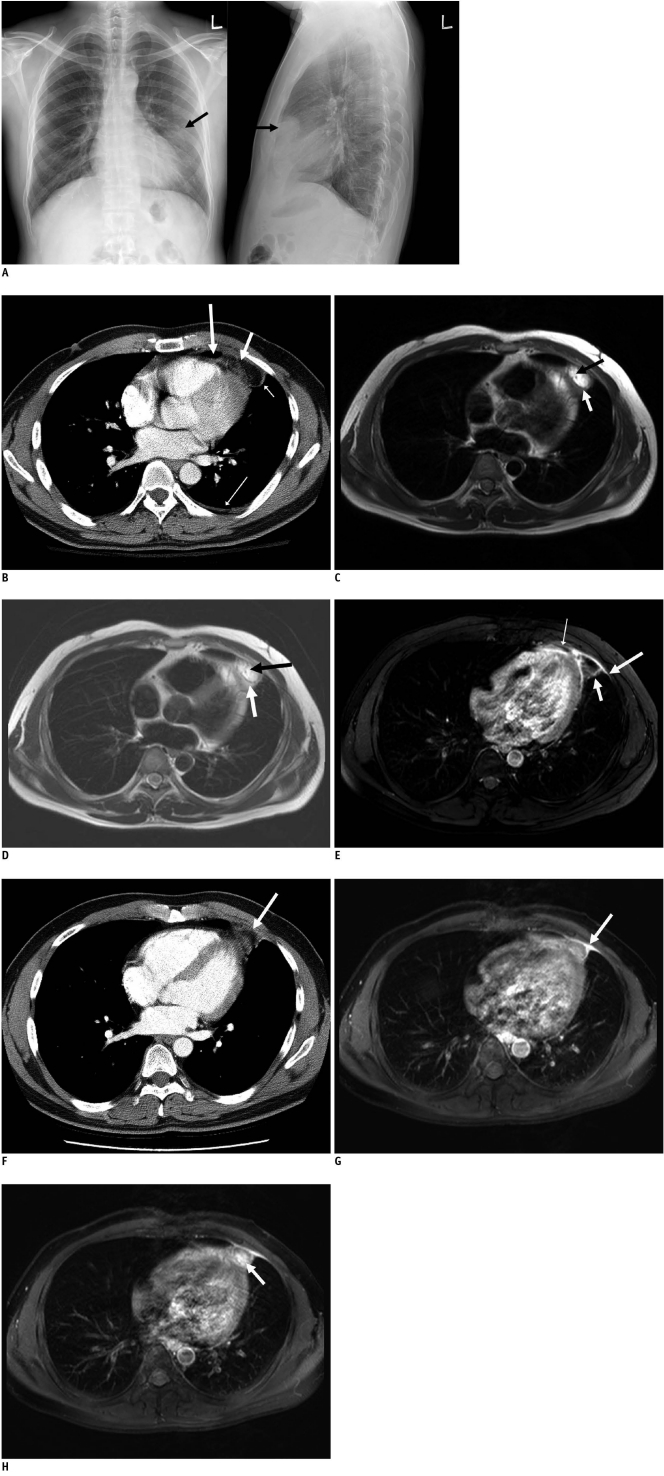

The chest PA and lateral radiographs showed an ovoid mass 6 cm in diameter with ill-defined margins in the left anterior mediastinum (Fig. 1A). Multidetector-row computed tomography (MDCT) showed a lesion adjacent to the pericardium with a low attenuation value (-90 Hounsfield unit [HU]) and this was surrounded by a capsule of high density, which was enhanced after administering IV contrast material (Fig. 1B). Slight thickening of the adjacent pericardium and a scanty pleural effusion in the left pleural space were also noted (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

39-year-old man with sudden onset left pleuritic chest pain.

A. Chest radiographs show ovoid mass (arrows) with ill-defined margins in left anterior mediastinum. B. Enhanced CT scans show that paracardiac opacity corresponded to pericardial fat surrounded by thick rim (short thin arrow). Note associated pericardial thickening (long thick arrow), linear opacity (short thick arrow) and pleural effusion (long thin arrow). C. T1-weighted breath-hold turbo spin echo images show high signal lesion with thin hypointense rim (white arrow) and hypointense linear line (black arrow). D. T2-weighted breath-hold turbo spin echo images show high signal lesion with thin hypointense rim (white arrow) and hypointense linear line (black arrow). E. T1-weighted fat suppressed breath-hold turbo spin echo image 1 minute after gadolinium administration shows enhancement of rim (short thick arrow) and adjacent pericardium (thin arrow) and pleura (long thick arrow). F. Follow-up CT scan obtained two months after A shows that pericardial lesion has decreased in size (arrow). G. Follow-up T1-weighted fat-suppressed breath-hold turbo spin echo image obtained 1 minute after gadolinium administration and two months after image C shows peripheral rim enhancement of pericardial lesion (arrow). H. Follow-up T1-weighted fat-suppressed breath-hold turbo spin echo image obtained 5 minutes after gadolinium administration and two months after image C shows enhancement of central globular pattern (arrow) of pericardial lesion.

On the precontrast T1-weighted images (repetition time [TR]/echo time [TE]/flip angle [FA], 1000/25/90), the lesion showed high signal intensity with a peripheral low signal rim (Fig. 1C), as well as a low dot-and-line signal. The lesion had the same appearance on the T2-weighted images (TR/TE/echo train length [ETL], 2000/60/90) (Fig. 1D). The lesion was best visualized on the T1-weighted fat-suppressed turbo spin echo images (TR/TE/FA: 1000/25/90, section thickness: 6 mm) at one minute (Fig. 1E) after gadolinium administration. The low signal of the peripheral rim and the central dot-and-line showed increased enhancement; the adjacent pericardium and pleura were also enhanced along with a scanty pleural effusion being present (Fig. 1E). The lesion had the same appearance on the 5-minute delayed images. Based on these clinical and radiologic findings, the patient was tentatively diagnosed has having pericardial fat necrosis. Following treatment with analgesics for one week, the pain gradually decreased and resolved after one week. Two months later, the follow-up chest CT assessment showed a marked decrease in the size of the pericardial fat lesion and the adjacent pericardial thickening (Fig. 1F). The follow-up T1- and T2-weighted MRI images showed an oval-shaped fatty mass with a peripheral rim of low signal intensity and a decrease of the lesion size. The follow-up T1-weighted fat-suppressed turbo spin echo images at one minute following gadolinium administration showed peripheral rim enhancement of the lesion, which was similar to the previous MRI findings (Fig. 1G), whereas the 5-minute delayed MRI findings showed central globular enhancement of the lesion (Fig. 1H).

DISCUSSION

Pericardial fat necrosis is an uncommon benign condition of an unknown etiology (1). It manifests as acute pleuritic chest pain in previously health persons, and it mimics the pain experienced during myocardial infarction or pulmonary embolism. Although obesity may be a predisposing factor for pericardial fat necrosis, it can also occur in non-obese individuals, like our patient (1).

The pathogenesis of pericardial fat necrosis is unknown, Acute torsion of the pericardial fat may cause its ischemic necrosis (5). High positioned pericardial fat may therefore be a predisposing factor due to the high probability of acute torsion of the pericardial fat. Alternatively, the increased thoracic pressure related to a Valsalva's maneuver may increase the capillary pressure, which may lead to hemorrhagic necrosis (5).

Patients with pericardial fat necrosis do not require surgical intervention; in most cases, treatment with analgesics for one week was enough to relieve the chest pain (1). Therefore, imaging studies are very important to avoid unnecessary surgery.

The chest CT in our patient showed an encapsulated fatty lesion with inflammatory changes, including dense strands and thickening of the adjacent pericardium, and these findings are similar to those observed in patients with primary epiploic appendagitis in the peritoneal space (6).

The MRI findings of fat necrosis may vary due to the pathologic stages of fat necrosis. In the acute stage, the peripheral rim and the central dot-and-line of low signal intensity observed on the T1- and T2-weighted images are characteristic of pericardial fat necrosis. These MRI findings are similar to those in the patients with primary epiploic appendagitis (3), with the low signal central dot-and-line on the T1- and T2-weighted images corresponding to the histopathologic findings of fibrous septa in patients with primary epiploic appendagitis.

In previous studies, the postgadolinium T1-weighted fat suppression images of patients with pericardial fat necrosis have shown increased enhancement of the rim 1 and 5 minutes after the infusion of contrast material. This enhancement was likely to be reactive owing to the presence of vascularized fibrous or granulation tissue (2).

In the chronic stage of pericardial fat necrosis, central globular and peripheral rim enhancements have been observed on the 5-minute delayed enhanced images. This central globular enhancement was likely due to progressive fibroblastic proliferation, increased vascularity and a lymphocyte and histiocytic infiltration (7).

The postgadolinium T1-weighted fat-suppression images of our patient showed enhancement of the adjacent pleura and pericardium during the acute stage. Yet the pleura did not show enhancement on the CT images. Pleural enhancement on MRI has not been previously reported in the English-language medical literature.

Due to the subtle focal changes in pericardial fat, the CT findings may be misinterpreted or the pericardial fat necrosis can be overlooked. In these patients, MRI can confirm the fatty contents of the lesion by showing the hypointense strands, which are typical of pericardial fat necrosis.

MRI may also help to differentiate pericardial fat necrosis from other fatty tumors in the anterior mediastinum, including lipomas, thymolipomas and liposarcomas, because pericardial fat necrosis has a characteristic peripheral rim enhancement pattern on the post-gadolinium T1-weighted fat-suppressed turbo spin echo images.

In conclusion, the MRI findings characteristic of pericardial fat necrosis may be helpful to differentiate pericardial fat necrosis from other causes of acute chest pain and other types of fat-containing tumors in the cardiophrenic space of the anterior mediastinum (8).

References

- 1.Pineda V, Cáceres J, Andreu J, Vilar J, Domingo ML. Epipericardial fat necrosis: radiologic diagnosis and follow-up. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:1234–1236. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan LP, Gee R, Keogh C, Munk PL. Imaging features of fat necrosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:955–959. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.4.1810955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sirvanci M, Balci NC, Karaman K, Duran C, Karakas E. Primary epiploic appendagitis: MRI findings. Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;20:137–139. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(02)00478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inoue S, Fujino S, Tezuka N, Sawai S, Kontani K, Hanaoka J, et al. Encapsulated pericardial fat necrosis treated by video-assisted thoracic surgery: report of a case. Surg Today. 2000;30:739–743. doi: 10.1007/s005950070088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webster MW, Jr, Bahnson HT. Pericardial fat necrosis. Case report and review. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1974;67:430–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sirvanci M, Tekelioglu MH, Duran C, Yardimci H, Onat L, Ozer K. Primary epiploic appendagitis: CT manifestations. Clin Imaging. 2000;24:357–361. doi: 10.1016/s0899-7071(00)00236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee BY, Song KS. Calcified chronic pericardial fat necrosis in localized lipomatosis of pericardium. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:W21–W24. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pineda V, Andreu J, Caceres J, Merino X, Varona D, Dominguez-Oronoz R. Lesions of the cardiophrenic space: findings at cross-sectional imaging. Radiographics. 2007;27:19–32. doi: 10.1148/rg.271065089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]